Settlement Outside Havana Isn’t the Refuge Many Hoped For

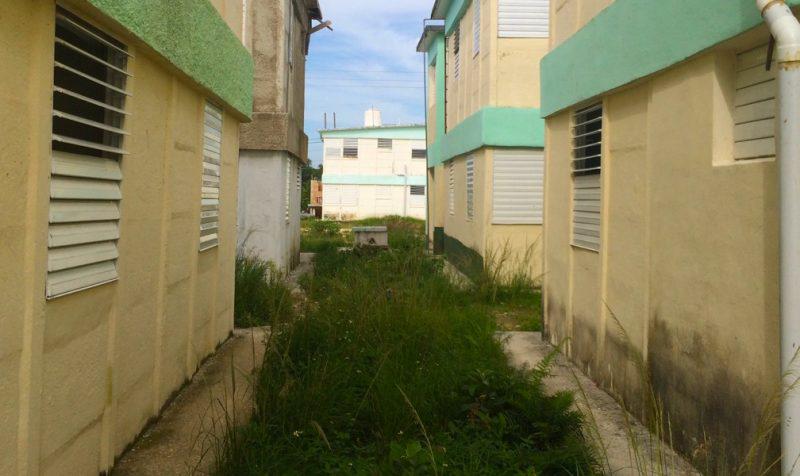

A look at the residential areas in the unsanitary neighborhood of Indaya. Photo by Elaine Díaz. Used with permission.

This article is an exclusive excerpt for Global Voices.You can find the original article, “Residential Areas of the Poor,” here and read other articles by Geisy Guia Delis for Periodismo de Barrio here.

Indaya is a community on the edge of the river Quibú, west of the Cuban capital. It is where one arrives after leaving behind a world of asphalt and concrete to surround oneself in a world of dirt, dust, and moisture. People who come from other provinces with the intention of living in Havana have created this group of “houses”.

Five hundred meters from the original Indaya — the one of mud and homes constructed with recycled materials or materials taken from the trash like zinc, wallpaper, or cardboard — different state-owned enterprises build a settlement with 102 residencies in the developed land, under the same name.

In 2012, bulldozers came to remove the dirt on the site that had been selected for the construction.

Initially, the Council of Provincial Administration (CPA) of Popular Power planned for the new homes to be ready in 2013. Since then, between 9 and 14 million pesos (9 to 14 million USD) have been assigned annually for the project. According to Greta Rodríguez, technical assistant manager of Living in Marianao, 11 million pesos (11 million USD) were given in 2016 and added:

El Estado quiere que esas casas se hagan, y no es poco el dinero que está dando para la obra.

The State wants these houses to be made and it's no small amount of money that they're providing for the project.

The instability of the supplies and the shortage of manual labor, as well as unrealistic deadlines that violated the construction processes postponed the project, and it still has no scheduled completion date.

Indaya. Photo by Elaine Díaz. Used with permission.

According to Tania Oliva, spokesperson for the Management of Architecture and Engineering Projects of Havana, which is managing the construction, the CPA assumed it would violate steps of the construction, when it set 2013 as the end date for the project.

The company City Design Havana (CDH) was in charge of planning the settlement in 2009. Idania Galíndez, one of the architects who was on the work team, says every unit had four homes in the original approved proposal: one with three bedrooms, one with two bedrooms, and two with one. The new settlement would include greenery, an area for sports, and other businesses.

Civil engineer René Rosabal asked to work with the best materials, and the project specified using supplies of the highest quality to give the project resistance and a finish that would ensure 50 years of durability (a number calculated by Rosabal).

The CDH had specified that the streets and sidewalks were included in the initial plan of construction for the settlement, among other reasons, because if they built the homes first, the vibrations from further machinery could create cracks and increase the risk of severe impact on the structures.

Nevertheless, they did an initial compaction of the ground, covered the patios with technical packing and immediately began to build the first houses. By the deadline, they had reportedly built 48 houses, but not a single street.

In the opinion of almost all of the interviewees, what stood out most, combined with the inexperience and actual execution of the project, was the quality of the allocated materials. On several occasions, Oliva had to send back entire shipments of sand and other supplies that weren't suitable for use. If the budget for this settlement is high compared to similar construction projects, it does not makes sense that such low-quality materials were received.

Cracks in the floor. Photo by Elaine Díaz. Used with permission.

The first houses were finished in 2015. More than a year later, none of those residents have the documents certifying that they are owners — paperwork that's required for performing home repairs. They don't even know how much they should pay for the property.

Carmelo Morejón has lived in one of the houses since 2016. When it rains a bit, traces of humidity stay on the roof and on some of its inside walls. In the first few months, he had to repair a clogged drain because the patio and the kitchen had filled with water. Leaks have also appeared in the children's bedroom and in the bathroom.

Morejón is not asking for a brigade to come solve all his problems. He just wants to be given the deed to his house, because that way he wouldn't have to worry about the inspectors. Right now, every time he tries to fix something, the inspectors fine him.

Humidity on the walls of Indaya. Foto by Elaine Díaz. Used with permission.

Ibrahim Masó complains because two of his doors open the wrong way. There are other problems in that house, too:

Estoy muy agradecido porque yo vivía muy mal, pero como yo hay gente que cuando recibió su casa no sabía qué hacer, si comprar los muebles o si comenzar a reparar una vivienda nueva.

I'm very grateful because I used to live very poorly, but like me, there are people who when they received their house, didn't know what to do, to buy furniture or to start to repair a new home.

Bárbara Díaz also moved in May. The day she arrived, she was immensely satisfied with the new roof, so much so that she wouldn't let herself open her eyes while lifting her face to the sky to give thanks.

Three days after the move, however, Bárbara began noticing the cracks in the roof that spread throughout the whole house, and her happiness soon disappeared. That was in May. By September, the polished floor had cracked and raised, leaving holes in the hard concrete.

Bárbara's building lacks a safety handrail on the stairs. Juana Herdia, Bárbara's 83-year-old, and has limited vision. For her and her two young grandsons, climbing up and down the stairs every day has become a harrowing tightrope walk.

The idea of the settlement is noble, it's a necessary action, however, if it needs to be dignified.

Originally published in Global Voices.