Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Apsy 674 Group D Intervention Plan

Uploaded by

api-160674927Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Apsy 674 Group D Intervention Plan

Uploaded by

api-160674927Copyright:

Available Formats

Running head: INTERVENTION PLAN

Intervention Plan: Case Study #2 - Carey Jo Friesen, Debby Kenna, Stephanie Poole, Shawna Sjoquist, & Stacy Thiry University of Calgary April 12, 2012 APSY 674: Interventions to promote social, emotional, and behavioural well-being

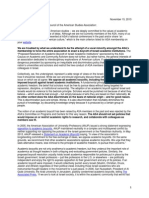

INTERVENTION PLAN Background Information (Stacy) Carey Tocher is a 7-year old girl who lives at home with her mother, Ms. Stacey Tocher. Ms. Tocher reports that she has brought Carey for a social, emotional, and behavioural assessment due to her concerns about recent changes in Careys behaviour. Strengths Carey is capable of appropriately engaging with peers within the school and home environment, and enjoys doing so. Ms. Tocher noted that in the past Carey frequently invited other children over for play dates and attended the homes of other children. Carey has previously demonstrated the ability to successfully separate from her mother as she has spent several evenings and weekends with her aunt and cousin while her mother worked, without displaying tantrum and avoidance behaviors. Ms. Tocher and teachers report that Carey often prefers to play alone, demonstrating that Carey can functionally occupy her time without relying on adults and peers. Carey demonstrates awareness regarding peer interaction, as she has commented that other children do not like her or want to play with her. Difficulties Carey struggles with transitioning and participating in activities when her mother is not present. She has difficulties with emotional regulation (worry, fear, sadness, and anxiety) in regards to anticipated or presented separation from her mother. When encountering a separation situation, Carey displays a variety of tantrum behaviours and psychosomatic symptoms. It is a challenge for Carey to attend school and if she does attend, she struggles with completing assigned work, engaging with peers, and being an active participant. Carey often plays alone and has difficulties with maintaining friendships and appropriately socializing with peers at school.

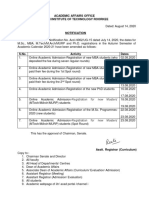

INTERVENTION PLAN Another area of challenge is Careys sleep routine, as she struggles with waking up at a developmentally appropriate time. Medication and Involvement Carey does not currently take any prescription medication. At this point, only Careys mother and teachers have been actively involved in the assessment. We would like to involve other school personnel (such as the school counselor), Careys aunt and cousin, and her peers. Global and Narrow Goals (Stacy) According to Upah and Tilly (2002), goals describe the outcome of the intervention. For Carey, we have identified four overarching global goals along with several narrow goals. The narrow goals are the main focus and directly targeted. As narrow goals are achieved, we will see progress made for the related global goals. Careys goals are outlined in Table 1. Table 1 Carey Tocher: Global and Narrow Goals Global Goal To improve Careys emotional functioning Narrow Goals To improve Careys ability to identify and regulate her emotions. To engage in appropriate strategies to cope with distressing emotions. To engage in coping strategies when presented with anxiety provoking events. To increase communication of her emotions to her mother and other adults (e.g., teachers, aunt). To improve Careys self-esteem, self-worth, and self-concept.

To improve Careys emotional functioning

To improve Careys ability to identify and regulate her emotions. To engage in appropriate strategies to cope with distressing emotions. To engage in coping strategies when presented with anxiety provoking events. To increase communication of her emotions to her mother and other adults (e.g., teachers, aunt). To improve Careys self-esteem, self-worth, and self-concept.

INTERVENTION PLAN

To improve Careys behavioral functioning

To decrease Careys engagement in maladaptive and attention seeking behaviours (e.g., crying and aggression). To decrease Careys use of psychosomatic symptoms. To sleep a developmentally appropriate number of hours at night. To wake up in the morning when directed by her mother. To attend her aunts house without her mother being present. To have Carey attend school and participate without complaints of being ill or crying inconsolably. To remain at a specified location (school, aunts house) until she is picked up by her mother at a predetermined time (end of the school day, after Careys mother is off work). To attend play dates at the homes of peers from school or neighbours without her mother. To participate in an extra-curricular activity, after being dropped off by her mother.

To help Carey to successfully transition away from her mother across multiple environments without displaying tantrum behaviors (e.g., crying and aggression)

Evidence-Based Intervention: FRIENDS for Life Carey displays a number of symptoms associated with anxiety, including several related to separation. These symptoms are causing significant social, emotional, and academic difficulties for Carey, as well as emotional, social, and work-related difficulties for Ms. Tocher. Based on Carey's identified areas of need, she will be provided a comprehensive treatment program that will include home, school, and community strategies, in addition to an empirically based anxiety prevention program: the FRIENDS for Life program. The FRIENDS for Life program teaches anxiety management skills through: identification of physiological reaction (body cues), relaxation and mindfulness strategies, awareness of cognitions (self-talk identification), awareness of cognitions or self-talk identification of unhelp and helpful thoughts, development of helpful coping thought, gradual exposure exercises, problem-solving strategies, identification of support people, how to selfreward, awareness of physical and mental health promotion. The FRIENDS for Life program teaches prosocial behaviour and social connectedness through: peer group activities, personal

INTERVENTION PLAN information sharing and listening, identification and appreciation of individual differences, promotion of school and community activities, personal and group contribution to care for environment, and home/family activities (Alberta Health Services, 2012). Background of the FRIENDS Program (Stephanie) One of the first cognitive-behavioural interventions designed for the treatment of childhood anxiety was the Coping Cat program, developed by Phillip Kendall in the 1980s (Briesch, Hagermsoer, & Briesch, 2010). Coping Cat was developed as a targeted intervention to treat children identified and diagnosed with anxiety, separation anxiety, or avoidant disorder (Barrett & May, 2007). The program was designed to teach children to identify anxious feelings, cognitions and situational triggers, to utilize behavioural strategies and positive self-talk, and to reinforce the use of these strategies (Briesch et al., 2010). In 1991, Coping Cat was modified and extended into Coping Koala by Dr. Paula Barrett to include a group format with an added family intervention component (Barrett and May, 2007). A revision to Coping Koala occurred in in 1998 when Dr. Barrett and researchers from Griffith University (Queensland, Australia) expanded the program to include two age groups: FRIENDS for Children (for students age 7-11 years), and FRIENDS for Youth (for students age 12-16). Several revisions to FRIENDS have occurred, with recent editions incorporating the latest research advances in childhood anxiety, depression, and resiliency. Consideration has also been given to teacher and clinician support information, and to feedback from those (i.e., students, parents, and teachers) who have benefited from FRIENDS. To reflect the life-long benefits provided by the program, a new title, FRIENDS for Life (2005) was introduced. For the remainder of this intervention plan, the FRIENDS for Life program will be referred to simply as FRIENDS.

INTERVENTION PLAN Evidence-Based Support for FRIENDS (Stephanie) Significant evidence exists to support the efficacy FRIENDS as a universal school-based intervention for anxiety. Based on comprehensive validation and randomized controlled studies across several languages and countries, FRIENDS is the only childhood anxiety prevention and treatment program acknowledged by the World Health Organization (Barrett and May, 2007). According to a study by Lowry-Webster, Barrett, and Dadds (2001), children who participated in FRIENDS reported fewer anxiety symptoms post-intervention, regardless of risk status, than those in the control group. A one-year follow-up of this study also found that intervention gains were maintained as measured by self-reports and diagnostic interviews. More specifically, 85% of the children in the intervention group who scored above the clinical cut-off for anxiety and depression at pre-test were diagnosis-free one year later, compared to only 31.2% of children in the control group (Lowry-Webster, Barrett, Lock, 2003). Literature to support the effectiveness of FRIENDS with students across ages, settings, type of delivery, cultures, and level of risk for anxiety problems continues to grow (Briesch et al., 2010). Lock and Barrett (2003) investigated the effects of FRIENDS at two developmental stages; Grade 6 and Grade 9. Findings were consistent with previous research supporting the program as an effective universal intervention in reducing symptoms of anxiety and increasing coping skills in children. However, age appeared to be a factor in the efficacy of FRIENDS. Specifically, primary school children (grade 6) reported more significant changes in anxiety symptoms, suggesting treatment is more successful when implemented with younger students. Further investigation into long-term treatment effects was conducted by Barrett, Farrell, Ollendick, and Dadds (2006). Results of this study demonstrated that significant reductions in anxiety and depression were maintained at 12, 24, and 36 months in those students who had

INTERVENTION PLAN completed FRIENDS, compared to those in the control group. Some gender differences were noted as girls in the intervention group reported significantly lower anxiety at 12 and 24 month follow-up; however, improvements were not maintained at 36-months. Research has also demonstrated the effectiveness of FRIENDS when used outside a school setting. Farrell and Barrett (2005) found significant improvement in children in a community-based clinic diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, with 73% of participants no longer meeting criteria for the disorder post-intervention. Evidence also exists supporting the efficacy of FRIENDS regardless of format of delivery. Liber et al. (2008) reported forty-eight percent of the children in the individual condition and 41% of the children in the group condition were free of any anxiety disorder post-treatment. As children demonstrated improvement in both conditions, determinations regarding treatment delivery (individual versus group) could be made based on other considerations such as child or parent preference, referral rates, cost, or therapeutic resources. FRIENDS has also been demonstrated to effectively reduce anxiety symptoms when delivered by trained school nurses (Stallard, Simpson, Anderson, and Goddard, 2008), teachers, or psychologists (Barrett and Turner, 2001). While most research supporting the efficacy of FRIENDS has taken place in Australia, studies conducted in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada have demonstrated similar results (Barrett & May, 2007). In addition, numerous overseas trials in Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Finland, and Mexico have shown the effectiveness of FRIENDS when translated into other languages. FRIENDS has also been demonstrated to be effective with students from various backgrounds. FRIENDS is effective in significantly decreasing both anxiety and depressive symptoms in students from socio-economically disadvantaged communities, and helps to improve self-esteem and the use of coping strategies, and to reduce

INTERVENTION PLAN peer and conduct problems (Stopa, Barrett, & Golingi, 2010). FRIENDS has also been demonstrated to significantly decrease general anxiety and manifestations of anxiety (i.e., physiological symptoms, worry regarding environmental pressures, and concentration difficulties) in community violence-exposed youth (Cooley-Quille, Boyd & Grados, 2004). Rationale (Shawna) Selection of FRIENDS was rationalized by considering availability, resources, relevant research and goodness of fit given case specific targeted behaviours, emotions and overall skills of the intervention. FRIENDS requires its facilitators to receive training provided by accredited program trainers prior to implementation of the program. In addition to an understanding of standardized program implementation, the certification process ensures facilitators are provided a thorough awareness of prevalence of anxiety and depression, costs of suffering relating to anxiety or depressive related symptoms, effects of limited individual potential and the importance of prevention itself (Alberta Health Services, 2012). The accredited training requirement necessitated by FRIENDS is viewed as a substantial strength supporting the presented rationalization of using FRIENDS as a primary treatment approach. At this time, training and implementation of FRIENDS is currently available through a promotional grant provided by the governing provincial health body. The available funding is intended to promote use of FRIENDS in schools as part of a partnership between provincial health and education organizations currently gathering data regarding consideration for curricular implementation. The one-day training is available through Pathways Health and Research Center and costs associated with implementation of the program, including training and program manuals are provided by the aforementioned funding. The curricular consideration, presence, availability and

INTERVENTION PLAN applicability of associated funding opportunities related to FRIENDS have been considered and strengthen the rationalization for use of FRIENDS in this case. In choosing this program for Carey, consideration was given to both target behaviors and goals. Carey is demonstrating avoidance in home and school environments, psychosomatic complaints, difficulty resting and going to sleep, fast and sustained physiological arousal, reduction in social activity, social withdrawal and social rejection. Using principles based in Cognitive Behavioural Theory, FRIENDS will provide Carey skills to cope with the identified physiological, cognitive, learning and behavioural processes (Barrett, 2012). Further, research indicates that use of FRIENDS has proven to reduce the incidence of serious psychological disorders, emotional distress and impairment in social functioning by teaching children how to manage current and future anxiety (Barrett, 2012). Evidence that Carey struggles with issues related to fear, anxiety, sadness, and worry further support the rationalization for use of FRIENDS. These emotions support instances of distress, interference, developmental inappropriateness, and duration that are consistent with an anxiety related disturbance. Careys distress is out of proportion to the associated threat, interferes with both her and her mothers lives, occurs past what would be developmentally expected and has lingered for a period of six months or more. Moreover, in considering Careys emotional and behavioral profile we see connections to a depressive characterization. Depression is defined as an emotional state marked by great sadness and apprehension, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, withdrawal from others, changes in sleep and or appetite and loss of interest and pleasure in usual activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Further, research indicates that anxiety disorders in childhood are associated with elevated risk for adult anxiety and depression (Silverman & Treffers, 2001). While no formal diagnosis has been identified, examination of Careys presenting emotions

INTERVENTION PLAN indicates that an intervention proven to target anxiety and depression related symptomology, such as FRIENDS, is an appropriate course of action. Specifically, FRIENDS is effective in intervening both proactively and reactively in situations where anxiety and or depression may present as a concern. While FRIENDS recognizes specific anxiety and depression related symptoms, it also recognizes that a normalized representation of anxious behaviours can typically present as an individual encounters everyday life. Anxiety symptoms and disorders have been found to significantly interfere with the ability to confidently cope with a variety of everyday activities and may lead to difficulty with interpersonal interactions, social competence, peer relations and school adjustment (Erickson & Newman, 2007; Hudson, McLoone & Rapee, 2006). FRIENDS promotes important personal development concepts such as identity, self-esteem, problem solving, self-expression and building positive relationships with peer and adults (Barrett, 2012). Further, the intervention addresses specific skills such as the awareness of body clues, relaxation and deep breathing, positive self-talk, self-reward, problem solving, exposure, and experiential learning (Barrett, 2012). Considering the timely availability, promotion and fit, FRIENDS is believed to be a well suited evidence based program for use with Carey. Intervention Implementation (Shawna) FRIENDS is divided into three program levels that are designed to target children at developmentally appropriate age intervals. The Fun FRIENDS program is designed to target children ranging in age from 4 years to 7 years, the FRIENDS for Life is designed to target children ranging in age from 7 to 11 years and the FRIENDS for Life Youth program is designed to target children ranging in age from 12 to 16 years. Implementation of the FRIENDS program will begin with use of the FRIENDS for Life program and continue at age appropriate intervals

10

INTERVENTION PLAN with the FRIENDS for Life Youth program as required. Implementation of the program will occur in a small group setting of four same age peers at the school facilitated by the school counsellor who has been trained to implement FRIENDS. Informed consent to participate in the program will be obtained prior to commencing participation in the program. Parents will be informed about the program premise, goals and targeted skills to be acquired. Participants of the program will each be provided individual workbooks that will remain in a secure area, used during each session of the program and provided to the owner to take away upon completion of the program. Home activities will be provided on a weekly basis to program participants and their families. Program implementation will further include processes to ensure intervention effectiveness and treatment integrity, recommendation of in home strategies, classroom strategies, school wide interventions and community resources which will be discussed in more depth in the sections to follow. Length of Intervention (Shawna) Participation in the program will take place on a weekly basis during a regularly scheduled health subject allotment so as to minimally interfere with core academic and student preferred activities. Sessions will occur on Thursday afternoons allowing the children the opportunity to both reflect and discuss the events of that current day, as well as the events that may have occurred earlier in the week. The program will occur once per week for 10 weeks, with two booster sessions to follow. Booster session one will occur one month post 10-week intervention and the second will occur three months post completion of the 10-week intervention. Two optional parent sessions will be offered during the 10-week implementation period and will be scheduled according to parent availability following week three of the program.

11

INTERVENTION PLAN Individuals Involved in Intervention (Shawna) Several individuals will be involved in the treatment process in varying capacities. As previously mentioned, FRIENDS will be facilitated by the school counsellor following a formal training and certification process. Subsequent school staff will also be provided the opportunity to become certified program facilitators as a means of increasing competency and awareness of FRIENDS. School administration, though not directly involved in the formal treatment processes, will be involved in all decisions related to implementation of the program, including consent to allocation of resources, staff training, accession of the identified funding opportunity and assisted facilitation of any school wide universal intervention program. The classroom teacher will be provided the opportunity to become a certified FRIENDS facilitator and will be instrumental in implementing classroom-based strategies. Students, including Carey, will take on an active role in treatment participation along with their families through participation in weekly discussion and experientially based learning activities. Specifically, it is recommended that Ms. Tocher takes part in the program and facilitates family practice of FRIENDS strategies 10 to 15 minutes 3 times a week. Regular practice will improve Carey's resiliency coping skills and her ability to apply them to family and school environments. Careys aunt and cousin are also encouraged to participate in practicing the skills with Carey and Ms. Tocher where possible. Determining Effectiveness (Stephanie) When evaluating the effectiveness of FRIENDS, several measures will be administered to Carey, her mother, and her teacher. First and foremost, tools for student self-report, conducted pre- and post-intervention, will be included in program evaluation. One such self-report anxiety measure, the Anxiety Inventory included in the Beck Youth Inventories-Second Edition for Children and Adolescents (BYI-II, Beck, Beck and Jolly, 2005) will provide clinicians with

12

INTERVENTION PLAN information regarding anxious symptomatology. This measure is designed for children and youth ages 7-18 and contains questions about thoughts, feelings, and behaviours associated with anxiety. Specifically, the anxiety inventory contains 20 questions that reflect specific worries about fears, the future, negative reactions from others, school performance, and physiological symptoms associated with anxiety. The anxiety inventory of the BYI-II is suitable for either individual or group administration and takes only five minutes to complete. In addition to assessments measures designed to specifically evaluate symptoms of anxiety, a broad behavioural rating scale will be an effective tool in evaluating treatments pre- and postintervention. For example, the Behavior Assessment System for Children- Second Edition (BASC-2; Kamphaus and Reynolds, 2004) provides a tool to help assess behaviours and emotions of individuals aged 2-25 years. Another advantage of using this type of measure is it allows for parent and teacher ratings in addition to self-report. The parent and teacher rating scales can be used for ages 2-21 years and take approximately 10-20 minutes to complete. The self-report measures of the BASC-2 include a self-report interview for children ages 6-7 and three self-report scales for children, adolescents, and college age (8-11 years, 12-21 years, and 18-25 years respectively). In addition to these rating scales, diagnostic criteria will be a focus for consideration when evaluating anxious symptomatology pre- and post-intervention. Anecdotal reports from the child, parents, and teachers will also be informative. Ensuring Treatment Integrity (Stephanie) Several steps will be taken to ensure treatment integrity during program implementation. As a manual based program, detailed descriptions of sessions and activities are provided to enable program fidelity. According to Briesch et al. (2010), studies to date have supported 1-2 day training to effective in providing teachers, psychologist, or other school-based mental health

13

INTERVENTION PLAN workers the necessary skills and knowledge to ensure proper program implementation. The integrity of the treatment protocol will also be measured by requiring implementers to complete checklists (e.g., Likert-type scale) after each session reflecting compliance with the activities provided in the manual (Barrett and Turner, 2001). In addition, a minimum of 25% of treatment session will be observed, either live or by video recording, by an independent trainer from health services (Barrett and Turner, 2001). Classroom-based Strategies (Jo) Careys teacher and other school personnel (such as the school counselor) will need to play an important role in Careys intervention. They are in the best position to ensure that Careys transition back to full-time school attendance is well supported, both in the classroom and around the school (Doobay, 2008). While the main emphasis of Careys intervention will consist of the participating in FRIENDS, she will continue to need support from other adults to ensure that is able to successfully overcome her school refusal, and be better equipped to cope with her anxiety moving forward. As noted, it is recommended that Careys teacher undergo training in regards to FRIENDS in order to be better equipped to support her in the classroom and to be knowledgeable of specific FRIENDS strategies to use within the classroom. In addition to FRIENDS related strategies, there are a number of other strategies Careys teacher can work to incorporate within the classroom to help to help Carey to meet her global goals: Social Functioning Carefully recruit one or two students to intentionally support Careys return to class by inviting her to participate in activities, choosing her for partner/team activities and sitting

14

INTERVENTION PLAN together during group activities. Plan activities that allow Carey to work with trusted peers who will welcome and encourage her. Observe Careys social functioning with her peers and use specific compliments to encourage positive social interaction. If needed, use modeling or peer observations to help Carey to understand how to correct negative social interactions she may engage in. Intentionally protect Carey from situations and students who may create a negative social situation for Carey. This may include desk placement in the classroom, as well as monitoring on the playground. Emotional Functioning If Carey gets emotional, validate her emotions. Acknowledge what she is feeling and help her to determine what is making her feel that way, as well as what may be triggering her emotions. Notice and acknowledge Careys somatic complaints, and try to help Carey to see how they are related to her feelings. Incorporate techniques from FRIENDS into the general classroom experience. This will help to reduce any stigma Carey feels about engaging in these activities, and help to create a supportive peer environment, both for Carey and her classmates. For example, teach all of the children about Milkshake Breathing and incorporate daily relaxation breaks into the class routine. Use games and activities from the FRIENDS Extra Games and Activity Ideas Resource to promote emotional development within the whole classroom. Age appropriate activities include: Sharing Positives, Feelings Thermometer, Robots, Towers & Jellyfish, Paintings based on My Many Colored Days by Dr. Seuss. Having the whole class

15

INTERVENTION PLAN involved will also help to normalize these types of activities for Carey so she feels less alone and will provide a more supportive environment for all of the children in the class. Cognitive/Behavioral Functioning and School Refusal Behaviors Help Carey to set small, realistic goals for her behavior within the classroom. Reward progress towards those goals, in addition to reaching the goals. Encourage Carey to articulate her thinking process when she is stressed or anxious. Help her to work through the process of restructuring her thoughts (e.g. using the Green/Red thought process from FRIENDS curriculum). Considering her age, Carey may need significant modeling and scaffolding to fully understand this process and be able to complete it independently. Help Carey to brainstorm a list of things she can try when she begins to feel anxiety about being a school. This can include strategies learned within FRIENDS (such as a relaxation technique or a cognitive restructuring activity), or seeking a quiet, safe place (such as the school counselors office). Support Carey by providing her with the time/space to follow through on these activities, preferably in a way that does not single her out from her peers. Encourage any positive behavior around school attendance and involvement. This could include special privileges in class if she attends all 5 days one week, rewards for answering out loud in class, or praise for volunteering to help a classmate. Discuss with Carey which activities she enjoys most and find ways to incorporate those pleasant activities into the classroom routine. Allowing Carey to have a calming, relaxing, non-disruptive activity she can turn to in the classroom when she is stressed may help to redirect her from wanting to go home.

16

INTERVENTION PLAN In co-operation with Ms. Tocher, set boundaries regarding Carey contacting her mother during school hours. Do not reward any oppositional behavior Carey uses to attempt to increase contact with her mother. At the end of each day, help Carey to brainstorm one thing to look forward to about the next day of school. Home Strategies, Family Support & Community Resources (Debby) Family Recommendations A great deal of research supports parental involvement and home support. Bernstein (2007) and Wood (2006) cite several studies that indicate significantly greater efficacy in the treatment of anxiety when parental support is present. Bernstein (2007) emphasizes parental involvement when the anxiety is severe or co-morbid, the child is young, and the parents are maintaining the anxiety by avoidance techniques. Careys anxiety is causing significant distress and impairment in home, school, and social environments. This is indicated by her avoidance to attend school, go to places that she once found pleasurable (e.g., her aunts home) and socialize with individuals that she once enjoyed socializing with (e.g., school friends and cousins). Careys anxiety is moderately to severely impacting her functioning given that her impairments are inhibiting sleep patterns, socialization, and learning. Also, there is possible comorbidity of several different anxiety disorders. Therefore, considering Careys age as well as the severity and co-morbidity of her anxiety, it is recommended that Ms. Tocher take an active role in treatment. Medication and CBT According to Bernstein (2007), Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) plus SSRIs in combination are the most efficacious when treating moderate to severe anxiety impairment in children. It is recommended that Ms. Tocher takes Carey to a pediatrician for a full medical

17

INTERVENTION PLAN assessment and counsel regarding the potential of SSRI medication and to rule out any additional medical ailments that could cause similar somatic symptoms such as hypo-thyroid, allergies, or diabetes etc. Ms. Tocher can also find information on SSRI medication and the risks for its use on The National Institute of Mental Health website (link provide in Appendix A). Psychoeducation In addition to supporting Careys involvement in FRIENDS, it is advised that Ms. Tocher and Carey talk to and seek the help of a trained child counsellor to help identify the cause and triggers of the anxiety. The Ministry for Children and Families offers Counselling for Childhood Anxiety, which includes free therapy for children and families (see Appendix A). Ms. Tocher may find that reading Carey childrens books that are written on the topic of anxiety may offer an opportunity for open discussion and as such may be used as a valuable home tool to help Carey identify her feelings and determine the triggers of her anxiety and how to handle them. The following storybooks may help: David and the Worry Beast by Anne Marie Guanci When My Worries Get Too Big by Kari D. Buron Nobody's Perfect by Ellen Burns What to Do When You Worry Too Much by Dawn Huebner I Don't Want to Go to School by Nancy Pando

18

There are also a number of recommended websites that Ms. Tocher may wish to consult which explain anxiety disorders, symptoms, treatment, how to help loved ones during treatment, and maintenance phases of anxiety (see Appendix A). Somatic Management Carey is experiencing fatigue, irritability, and general lethargy. It will be important for Ms. Tocher to provide peaceful quiet time at home to combat these somatizations. Regular exercise will also help combat Careys stress and anxiety (Briesch, 2010). Lastly, it is

INTERVENTION PLAN recommended that Ms. Tocher establishes a bedtime routine that begins early enough to foster adequate age-appropriate rest. Doing so will institute healthy rest schedules and habits. Cognitive Restructuring Cognitive restructuring is the identification of distorted thoughts and changing thought patterns that promote anxiety. Transfer of cognitive restructuring that is learned during FRIENDS to the home environment is an important part of Careys therapy. Ms. Tocher will be required to attend parent sessions during which she will also learn the skills that are being taught to Carey, such as body clues, relaxation techniques, deep breathing, positive self-talk, selfreward, problem solving techniques and exposure exercises. Skills such as positive self-talk in the home will help Carey feel more in control of her life. It will be helpful to have Ms. Tocher model skills and encourage Carey to transfer these learned skills into their home and community environment. Problem-Solving Strategies FRIENDS provides a problem-solving plan to the participants which includes brainstorming and listing solutions, selecting the best solution based on consequence, devising a plan, and evaluate the outcome. This would be a good problem-solving model to reinforce in the home and would help Carey feel more in control. Exposure Depending upon her anxiety triggers, a coping strategy may be necessary in order to undergo graded exposure to her feared stimuli. It is recommended that Carey undergoes graded exposure with the guidance of a trained counsellor to successfully desensitize and not exacerbate her fears. Given that Carey is currently withdrawing from her social and peer group, Ms. Tocher may need to gradually introduce her to a fresh group of friends, when she is ready. Social groups

19

INTERVENTION PLAN such as the boys and girls club, sports groups, church youth groups, rec-center activities or swimming venues may promote external socialization. Encouraging a friendship network will insulate her and help her combat future stressors in life. Community Resources (Debby) In addition to the ways in which Ms. Tocher and Carey will interact with their local community through the recommended home and family support strategies, there are a number of additional community resources that may be helpful in supporting Careys healthy development. Brownies, Boys and Girls Club, Ballet or Gymnastics involvement would allow Carey exposure opportunities to overcome her social fears while building social connections, establishing new friendships and social skills that are fresh and not focused around school. These fun activities may provide a non-threatening venue for her. Contact information for specific groups is provided in Appendix A. To support additional physical activity for both Carey and Ms. Tocher, as well as to develop additional social connections, it is recommended they take advantage of the park and recreation activities provided in their community. The city of Langley has a number of recreation centers, skateboard parks, and indoor/outdoor pools to choose from. The City of Langley also has quarterly registration brochures that describe a number of structured recreation activities that might interest the individual as well as detailed instructions for registration. Most of these programs require fee payment. Specific facilities and contact information can be found in Appendix A. Relapse Prevention and Maintenance Carey will require constant reminders, encouragement, reassurance, and reinforcement from her home support team. It will be vital that Ms. Tocher reinforces how much Carey has

20

INTERVENTION PLAN learned and reminds her that these skills can and will be used by Carey throughout her life when she encounters problems and anxiety. FRIENDS strategies can also be implemented for further prevention and for maintaining current successes. Finally, it is important to mention that Ms. Tocher needs to find ways to nurture her own emotional health in order to be strong enough to help Carey. She needs to find relief from her feelings of frustration, resentment and loss of patience. Counselling may be helpful for her as well. She may also find it helpful to take time to build a social support network. One option is to use a local website provides which provides links to social activities and support groups for parents in her community, including Moms morning out, Moms walking club, family support respite groups, mental health family support and respite, parenting support groups, community gardening sites, coffee social groups, meditation groups. In addition, the local YMCA and Community Rec Centers may have programs of interest for Ms. Tocher. We encourage Ms. Tocher to take the time for self-nurture after Carey has gone to bed, as this will strengthen Ms. Tocher and prepare her to support Carey in a healthy way. Follow-up (Stacy) It will be important to provide continued follow-up for Carey to ensure gains are maintained and to monitor any additional concerns. Two months following the implementation of FRIENDS, individual interviews will be arranged with Carey, her mother, and her teacher, in order to review progress on Careys global and narrow goals. Other school personnel may also be asked to participate if additional information is needed. In meeting with Carey, her current feelings regarding school, friends, her aunt, and her mother will be assessed. For post-intervention evaluation, she will be asked to repeat the two self-report measures, the Anxiety inventory from the BYI-II and the BASC; the former to

21

INTERVENTION PLAN determine her current level of anxiety and the latter to examine her present social, emotional, and behavioural functioning. Careys mother and teacher will also be asked to complete the BASC. The results of these measures will be compared with the results obtained in the pre-intervention evaluation. Further, Careys mother and teacher will be asked to review Careys global and narrow goals and for each one (relevant to their environment), indicate the level of progress Carey has made (0 no progress, 1 minimal progress, 2 moderate progress, or 3- significant progress/achieved). Original strategies and recommendations provided for global and narrow goals receiving a rating of 0 or 1 will be reviewed to determine if they had been utilized within the home and school environment. Relevant recommendations for goals receiving a low rating which have not yet been implemented will be encouraged. Ms. Tocher and Careys teacher will be asked to identify any barriers to implementing the suggested strategies or accessing resources. At this time Careys mother and teacher will be asked to identify what further supports are required to aid them in utilizing strategies and accessing resources recommended. Additional strategies will be provided if it is determined that the use of previously recommended strategies did not result in progress made for a narrow or global goal, or if a significant barrier was identified that prevented the implementation of the strategy. Twelve months following the conclusion of FRIENDS (eight months after the first follow-up session), Careys mother and teacher will be asked to complete the BASC, and once again review Careys global and narrow goals to determine her level of progress. Carey will be provided with the anxiety inventory from the BYI-II, to determine if a decrease in anxiety symptoms has been maintained. In addition, she will be asked to complete the BASC. The results from these measures will be compared to the results from the two-month follow-up. Global and narrow goals receiving a low rating (0 or 1) will be re-examined and discussed with

22

INTERVENTION PLAN Ms. Tocher and Careys teachers. Additional strategies will be provided for recommendations that did not demonstrate an increase in ranking or had significant barriers identified. Additional, if it is determined that Carey would benefit from repeated exposure to FRIENDS, the program may be implemented annually (continuing with FRIENDS for Life and then FRIENDS for Life Youth). School-wide Intervention Program (Jo) Many children with internalizing disorders are unlikely to be referred to mental health services (Mifsud & Rapee, 2005). Schools can help to bridge this gap by providing access to services within the school setting, both as part of the regular curriculum and with more specialized services (Mifsud & Rapee, 2005). Implementing school wide programs to support social and emotional development not only reduce the stigma of targeted programs, but also ensure that no students are missed, increase education and support among peers and ensure that teachers and other school personnel are involved in the process (Mifsud & Rapee, 2005). Specific to Careys case, it is recommended that the school consider implementation of programs that are designed recognize and support students with internalizing disorders (such as depression), as well as to ensure that school is a fun, creative, safe environment for all children. Some specific recommendations for the school are: Expand FRIENDS into a school-wide, classroom delivered program. This moves the program from intervention (as in Careys situation), to prevention. Having all students participate in the program will also help to create a culture of understanding and support around anxiety issues. Beyond FRIENDS, it is recommended the school create an ongoing Social and Emotional Learning class as part of the regular curriculum. FRIENDS could be constitute the

23

INTERVENTION PLAN initial curriculum, followed by age appropriate lessons in on topics such as coping skills, social skills, communication skills, conflict resolution skills, character building skills, or the implementation of other universal programs, such as the Strong Kids Program or the Caring Community School Program. Making this a regular, prioritized part of the curriculum will send the message to students, parents and teachers that the childrens emotional and social development is as important as their academic development. It will also help to decrease the stigma and ignorance that may surround social-emotional difficulties, and create a more educated, accepting culture. Teachers and administrators can use screeners to both prioritize topics, and to determine if additional support is needed. Institute a Big Buddy/Little Buddy Program. Having a big buddy can provide a role model to children (reference), as well as a mentor who can help them to learn from and work through challenges. Being a big buddy can provide a safe relationship where a child can practice social skills, take responsibility and learn to understand and respond to someone elses feelings. In Careys case, she could benefit from both having and older buddy (say a 4th/5th grader) and being an older buddy (to someone in Kindergarten). Promote the idea of school being a FUN place to be. o Incorporate special activity days (Wacky Hair Day, Pajama Day, Marshmallow Day) to give students days to look forward to. o Provide more elective and in class activities that allow teachers and students to explore activities they enjoy. For example, every Wednesday afternoon could be set aside for Electives, allowing children to choose from a group of activities from chess, to hockey, to embroidery, to cooking, to photography. The goal is to give kids a choice, to promote the idea the learning something new can be fun, and to allow children to explore their own gifts and talents. o A school-wide incentive program could promote good behavior, teamwork, responsibility and support for one another.

24

INTERVENTION PLAN Recommended Resources (Stacy) The following is a list of resources appropriate for school professionals and other practitioners. FRIENDS Teacher Resource CD (Children) To aid teachers with incorporating FRIENDS throughout the normal teaching year, FRIENDS Teacher Resource CD, is available for purchase from www.friendsinfo.net. Within the CD there are 27 activities that are available to be printed and used (in any order). The aim of these activities is to aid in building resiliency and enhance the natural educational components of FRIENDS. A teacher may use the CD without training in FRIENDS. FRIENDS Teacher Learning Outcome Sheets (Children) Available online at www.friendsinfo.net/friendsinschools.html, the sheets describe the educational outcomes associated with completion of FRIENDS. Caring School Community Caring school community is a multi-year school improvement program, involving all students in kindergarten through grade 6. The program aims to promote positive youth development. The program is designed to create a caring school environment evident through supporting and kind relationships, as well as collaboration between parents, staff, and students. There are four components: class meetings, cross-age buddy programs, homeside activities and school-wide community. Caring School Community is listed on SAMHSAs National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. Please refer to the following websites for more information: http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/ViewIntervention.aspx?id=152 and http://www.devstu.org/page/caring-school-community

25

INTERVENTION PLAN The Strong Kids Program A universal prevention program, the Strong Kids program is designed for students in kindergarten to grade 12. Through a brief and practical curriculum (12 lessons), the program promotes social and emotional health and aims to prevent the development of mental health concerns. For more information please visit http://strongkids.uoregon.edu/ Ministry of Children and Family Development This website outlines the teacher training and resources available within British Columbia through the Ministry of Children and Family development. The Ministry of Children and Family Development are currently funding the use of FRIENDS. The Ministry provides all training and program materials. For additional information please visit: http://www.mcf.gov.bc.ca/mental_health/friends_teacher.htm

26

INTERVENTION PLAN References Alberta Health Services (2012). Friends For Life: Trainer Manual (5th ed.). Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services and Austin Resilience Development Incorporated. Barrett, P. (2012). Friends for life: Group leaders manual for children. Australia: Pathways Health and Research Center. Barrett, P. M., Dadds, M. R., & Rapee, R. M. (1996). Family treatment of childhood anxiety: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 333-342. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ccp/index.aspx Barrett, P. M., Duffy, A. L., Dadds, M. R., & Rapee, R. M. (2001). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders in children: Long-term (6 year) follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 135-141. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ccp/index.aspx Barrett, P.M., Farrell, L.J., Ollendick, T.H., & Dadds, M. (2006). Long-term outcomes of an Australian universal prevention trial of anxiety and depression symptoms in children and youth: An evaluation of the friends program. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 403-411. Retrieved from http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/titles/15374416.asp Barrett, P. M., & May, A. (2007). FRIENDS for life: Introduction to FRIENDS. Australia: Pathways Health and Research Center. Beck, J. S., Beck, A. T., & Jolly, J. B. (2005). Beck youth inventories (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://www.pearsonassessments.com

27

INTERVENTION PLAN Bernstein, G. A., Layne, A.E., Egan, E. A., & Tennison, D. M., (2005). School-based interventions for anxious children. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 1118-1127. Retrieved from http://www.jaacap.com/ Bernstein, G.A., & Victor, A.M. (2007). Treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders. Pediatric Health, 1, 191-203. doi:10.2217/17455111.1.2.191 Briesch, A.M., Hagermoser Sanetti, L.M., & Briesch, J.M. (2010). Reducing the prevalence of anxiety in children and Adolescents: An Evaluation of the Evidence Base for the FRIENDS for Life Program. School Mental Health, 2, 155-165. doi:10.1007/s12310-0109042-5 Connolly, S. D., Suarez, L., Sylvester, C., (2011). Assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(2), 99-110. doi:1031007/s11920-010-01732 Cooley-Quille, M., Boyd, R. C., & Grados, J. J. (2004). Feasibility of an anxiety prevention intervention for community violence exposed children. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 25, 105-123. http://www.springer.com/medicine/journal/10935 Doobay, A.F. (2008). School refusal behavior associated with separation anxiety disorder: A cognitive-behavioral approach to treatment. Psychology in the Schools, 45, 261-272. doi:10.1002/pits.20299 Erickson, T. M., Newman, M. G., (2007). Interpersonal and emotional processes in generalized anxiety disorder analogues during social interaction tasks. Behaviour Therapy, 38, 364377. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.005. Farrell, L. J., & Barrett, P. M. (2005). Community trial of an evidence-based anxiety intervention for children and adolescents (the FRIENDS program): A pilot study.

28

INTERVENTION PLAN Behaviour Change, 22 (4), 236-248. Retrieved from http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=BEC Hudson, J. L., McLoone, J., & Rapee, R. M. (2006, May). Treating anxiety disorders in a school setting. Education & Treatment of Children, 29(2), 219-242. Retrieved from http://www.educationandtreatmentofchildren.net/ Liber, J. M., Van Widenfelt, B. M., Utens, E. M. W. J., Ferdinand, R. F., Van der Leeden, A. J. M., Van Gastel, W., & Treffers, P. D. A. (2008). No differences between group versus individual treatment of childhood anxiety disorders in a randomised clinical trial. Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 886-893. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01877.x Lock, S. & Barrett, P.M. (2003). A longitudinal study of developmental differences in universal prevention intervention for child anxiety. Behaviour Change, 20, 183-199. Retrieved from http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=BEC Lowry-Webster, H. M., Barrett, P. M., & Dadds, M. R. (2001). A universal prevention trial \ of anxiety and depressive symptomatology in childhood: Preliminary data from an Australian study. Behaviour Change, 18, 36-50. Retrieved from http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=BEC Lowry-Webster, H. M., Barrett, P. M., & Lock, S. (2003). A universal prevention trial of anxiety symptomatology during childhood: Results at one-year follow-up. Behaviour Change, 20 (1), 25-43. Retrieved from http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=BEC Mifsud, C., & Rapee, R. M. (2005). Early intervention for childhood anxiety in a school setting: Outcomes for an economically disadvantaged population. Journal of the American

29

INTERVENTION PLAN Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 996-1004. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000173294.13441.87 Reinblatt, S.P. & Walkup, J.T. (2005). Psychopharmacologic treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders. Child Adolescent Psychiatric Clinic of North America, 14, 877-908. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2005.06.004 Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2004). Behavior assessment system for children (2nd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. Seligman, L.D., & Ollendick, T.H., (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20(2), 217-238. ISSN 1056-4993 Shortt, A. L., Barrett, P. M., & Fox. T. L. (2001). Evaluating the FRIENDS program: A cognitive-behavioral group treatment of anxious children and their parents. Clinical Child Psychology, 30, (4), 525-535. Retrieved from http://journalseek.net/cgibin/journalseek/journalsearch.cgi?field=issn&query=0047-228X Silverman, W. K., & Treffers, P. D. A. (Eds.). (2001). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Research, assessment and intervention. New York: Cambridge University Press. Stallard, P., Simpson, N., Anderson, S., & Goddard, M. (2008). The FRIENDS emotional health prevention programme: 12 month follow-up of a universal UK school based trial. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 17, 283-289. doi:10.1007/s00787-007-0665-5 Stopa, E. J., Barrett, P. M., & Golingi, F. (2010). The prevention of childhood anxiety in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities: A universal school-based trial.

30

INTERVENTION PLAN Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 3 (4), 5-24. Retrieved from http://www.schoolmentalhealth.co.uk/ Upah, K.R., Tilly, W.D., III. (2002). Best practices in designing, implementing, and evaluating quality interventions. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology IV (pp. 483-501). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

31

INTERVENTION PLAN Appendix A Community and Family Resources (Debby) National Institute of Mental Health: Information regarding SSRI medications and the risks for use with anxiety: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/mental-health-medications/completeindex.shtml#pub7 Ministry of Children and Families in BC: Counselling for Childhood Anxiety: 604.660.9495 Recommended websites for Anxiety Information http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/anxiety-disorders/introduction.shtml (great for general information) http://www.anxietybc.com/ (website published by Anxiety BC. The site includes information on programs and resources as well as links to community services and support groups. There is even an option to follow with Twitter.) http://support-group.meetup.com/cities/ca/bc/langley/ (good site to find support group meetings in the Langley, B.C. area. You can search for whatever support group you are interested in, eg: childhood anxiety, and find a meeting. *Caution, research on the support network is advised before attending as this site is not professionally supported.) http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/ (American Psychological Association help website for general information.) http://www.adaa.org/ (Anxiety Disorders Association of America website for general information) Community Resource Links and Contact Information: Group Activities Boys and Girls Club in Langley, BC (604) 533-8552. This service provides recreation and social activities at a cost of only $25.00 per year, and no one is turned away for a lack of funds. Brownies in Langley, BC (604) 574-1827, or visit www.bc-girlguides.org Gymnastics classes in Langley, BC (604) 465-1329 Free 2 week trial http://www.mygym.com/mapleridge.aspx Girls Soccer in Langley, BC Beyond the Field Registration is on-line at http://www.beyondthefield.com/?gclid=CK3ctoThma8CFYZoKgodn2rFdQ Community Resource Links and Contact Information: Recreation Facilities Langley Parks and Recreation, BC (604) 514-2940 or www.city.langley.bc.ca There are o Willowbrook Rec Center, 20338 65th Ave, Langley, BC (604) 532-3500. o Langley Indoor Pools:

32

INTERVENTION PLAN WC Blair Wave Pool, 22200 Fraser Hwy. (604) 533-6170 Walnut Grove Pool, 8889 Walnut Grove Dr. (604) 882-0408 o Langley Outdoor Pools (summer only): Al Anderson Pool, 4949 207th St (604) 514-2860 Aldergrove Pool, 32nd Ave & 271st St (604) 856-6212 Fort Langley Pool, St Andrews & Nash (604) 882-0408 Aldergrove Lake Park, 7th Ave & 272nd St (604) 530-4983 o Langley Skateboard Parks: Brookswood Skateboard Park, 42nd Ave & 207th St South Aldergrove Park, 29th Ave & 276B St Langley Skateboard Park, 203rd St between 62nd and 64th Ave Murrayville Outdoor Activity Park, 48A Ave & 221st St Walnut Grove Skateboard Park, 88th Ave & Walnut Grove Dr. Social Activities and Support Groups http://www.langleyadvance.com/life/Community+Links/6364286/story.html

33

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Historical Influence of Adhd in School Psycholog2Document20 pagesHistorical Influence of Adhd in School Psycholog2api-162851533No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Fasds: Social and Emotional Interventions: University of Calgary Shawna Sjoquist Spring 2011Document16 pagesFasds: Social and Emotional Interventions: University of Calgary Shawna Sjoquist Spring 2011api-162851533No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- 657 Case Study OneDocument8 pages657 Case Study Oneapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Martin SplashDocument17 pagesMartin Splashapi-162851533No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Hearing Children of Deaf ParentsDocument20 pagesHearing Children of Deaf Parentsapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Finalpapersjoquist 1Document11 pagesFinalpapersjoquist 1api-162851533No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- PresentationDocument13 pagesPresentationapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 657 Case Study TwoDocument18 pages657 Case Study Twoapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Ed Opportunities of Adhd in School PsychDocument12 pagesEd Opportunities of Adhd in School Psychapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Fasds: Social and Emotional Interventions: University of Calgary Shawna Sjoquist Spring 2011Document16 pagesFasds: Social and Emotional Interventions: University of Calgary Shawna Sjoquist Spring 2011api-162851533No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Assumptions in Multiple RegressionDocument16 pagesAssumptions in Multiple Regressionapi-162851533100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- 603 Marked Ethical Decision Making ExerciseDocument22 pages603 Marked Ethical Decision Making Exerciseapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 657 Test ReviewDocument16 pages657 Test Reviewapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Sjoquist Math ComputationsDocument18 pagesSjoquist Math Computationsapi-162851533No ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Ethical Issues in Multicultural PopulationsDocument19 pagesEthical Issues in Multicultural Populationsapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Case Study PresentationDocument23 pagesCase Study Presentationapi-162851533No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Interview Assignment Reflection University of Calgary APSY 660 Shawna SjoquistDocument7 pagesInterview Assignment Reflection University of Calgary APSY 660 Shawna Sjoquistapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Treatment Efficacy in AdhdDocument15 pagesTreatment Efficacy in Adhdapi-162851533No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 603 Marked North Star Womenrevised ProjectDocument19 pages603 Marked North Star Womenrevised Projectapi-162851533No ratings yet

- 658 Anxiety HandoutDocument2 pages658 Anxiety Handoutapi-162851533No ratings yet

- 674 Journal Article ReviewDocument23 pages674 Journal Article Reviewapi-162851533No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 605 Parental Psych Control and Anxious Adjustment Research ProposalDocument18 pages605 Parental Psych Control and Anxious Adjustment Research Proposalapi-162851533No ratings yet

- 651 Final ExamDocument13 pages651 Final Examapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Interview Assignment Reflection University of Calgary APSY 660 Shawna SjoquistDocument7 pagesInterview Assignment Reflection University of Calgary APSY 660 Shawna Sjoquistapi-162851533No ratings yet

- 658 Sjoquist Best Practices PaperDocument14 pages658 Sjoquist Best Practices Paperapi-162851533No ratings yet

- Talks To Teachers PPRDocument13 pagesTalks To Teachers PPRapi-162851533No ratings yet

- MIS Management Information SystemDocument19 pagesMIS Management Information SystemNamrata Joshi100% (1)

- Solidarity Letter by non-ASA Member Americanist Scholars in Opposition To The ASA's "Proposed Resolution On AcademicBoycott of Israeli Academic Institutions"Document5 pagesSolidarity Letter by non-ASA Member Americanist Scholars in Opposition To The ASA's "Proposed Resolution On AcademicBoycott of Israeli Academic Institutions"ASAMembersLetterNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Testing and MeasurementDocument352 pagesTesting and MeasurementRABYANo ratings yet

- Details of Offer: Details of Offer:: Postgraduate - Admissions@swansea - Ac.uk Postgraduate - Admissions@swansea - Ac.ukDocument2 pagesDetails of Offer: Details of Offer:: Postgraduate - Admissions@swansea - Ac.uk Postgraduate - Admissions@swansea - Ac.ukAdetunji TaiwoNo ratings yet

- CTU Public Administration Thoughts and InstitutionDocument3 pagesCTU Public Administration Thoughts and InstitutionCatherine Adlawan-SanchezNo ratings yet

- Study To Fly ATP Flight Schoolwzuiw PDFDocument1 pageStudy To Fly ATP Flight Schoolwzuiw PDFMayerOh47No ratings yet

- Percentage Sheet - 04Document2 pagesPercentage Sheet - 04mukeshk4841258No ratings yet

- Exploratory Factor AnalysisDocument170 pagesExploratory Factor AnalysisSatyabrata Behera100% (7)

- Honorata de La RamaDocument20 pagesHonorata de La RamaAnnabelle Surat IgotNo ratings yet

- General Knowledge Solved Mcqs Practice TestDocument84 pagesGeneral Knowledge Solved Mcqs Practice TestUmber Ismail82% (11)

- Thesis University of SydneyDocument4 pagesThesis University of Sydneynikkismithmilwaukee100% (2)

- Fieldwork and The Perception of Everyday Life - Timothy Jenkins PDFDocument24 pagesFieldwork and The Perception of Everyday Life - Timothy Jenkins PDFIana Lopes AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Nakamura Tome Sc200Document52 pagesNakamura Tome Sc200JoKeRNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Amendment in Academic Calendar - AUTUMN 2020-21Document1 pageAmendment in Academic Calendar - AUTUMN 2020-21anurag mahajanNo ratings yet

- Bambang National High School Remedial Exam in Poetry AnalysisDocument1 pageBambang National High School Remedial Exam in Poetry AnalysisShai ReenNo ratings yet

- Quantum Mechanics A Paradigms Approach 1st Edition Mcintyre Solutions ManualDocument36 pagesQuantum Mechanics A Paradigms Approach 1st Edition Mcintyre Solutions ManualMicheleWallsertso100% (16)

- 10 Tools To Make A Bootable USB From An ISO FileDocument10 pages10 Tools To Make A Bootable USB From An ISO Filedds70No ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document6 pagesChapter 1Neriza Felix BaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Electrons and PhotonsDocument48 pagesElectrons and PhotonsVikashSubediNo ratings yet

- 2021-08-24 12-29-30-DIT-Selected Students To Join Undergraduate Degree Programmes Round One - 20212022Document14 pages2021-08-24 12-29-30-DIT-Selected Students To Join Undergraduate Degree Programmes Round One - 20212022EdNel SonNo ratings yet

- James Mallinson - On Modern Yoga's Sūryanamaskāra and VinyāsaDocument3 pagesJames Mallinson - On Modern Yoga's Sūryanamaskāra and VinyāsaHenningNo ratings yet

- Measures of Validity Report 2Document15 pagesMeasures of Validity Report 2Romeo Madrona JrNo ratings yet

- Razak Report 1956: EDU 3101 Philosophy of Malaysia EducationDocument15 pagesRazak Report 1956: EDU 3101 Philosophy of Malaysia EducationDadyana Dominic KajanNo ratings yet

- Written Communication ImportanceDocument3 pagesWritten Communication ImportanceAbdul Rehman100% (1)

- PSN School Haldwan8Document3 pagesPSN School Haldwan8PSN SchoolNo ratings yet

- Ebbs - Carnap, Quine, and Putnam On Methods of Inquiry-Cambridge University Press (2017)Document291 pagesEbbs - Carnap, Quine, and Putnam On Methods of Inquiry-Cambridge University Press (2017)Guillermo Nigro100% (1)

- The Gender and Leadership Wars: Gary N. PowellDocument9 pagesThe Gender and Leadership Wars: Gary N. PowellACNNo ratings yet

- Bathing Your Baby: When Should Newborns Get Their First Bath?Document5 pagesBathing Your Baby: When Should Newborns Get Their First Bath?Glads D. Ferrer-JimlanoNo ratings yet

- Project Electrical Best Practices: IEEE SAS/NCS IAS-PES Chapter SeminarDocument63 pagesProject Electrical Best Practices: IEEE SAS/NCS IAS-PES Chapter SeminarAlex ChoongNo ratings yet

- Term Paper Recommendation SampleDocument4 pagesTerm Paper Recommendation Sampleafdtfhtut100% (1)