Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Congress and Pressure Groups Senate-CRS 1986 Report

Uploaded by

Sunlight Foundation0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

67 views46 pagesCopyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

67 views46 pagesCongress and Pressure Groups Senate-CRS 1986 Report

Uploaded by

Sunlight FoundationCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 46

SP

smn Cones

vmconer | cosnrenss px Er

ONGRESS AND PRESSURE GROUPS:

IBBYING IN A MODERN DEMOCRACY

or-tme

COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS

UNITED STATES SENATE

BY THE

CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

JUNE 1986

Printed for the use of the Committee on Gorernmental Affairs

‘Pore te Supine of Dass, Gmgrinn Sles Oto

‘US Goverunt Pring Of, Wahingen DC 2UG2

a oy

Mo Svan

“CouurTER oN ob YennMENTAL AFFAIRS

~WItLAME-woROfiY, Jn, Delaware, Charman

TED STEVENS, Alashe THOMAS F. BACLETON, Missur)

GHARLES NeC. MATIIIAS, Ja, Maryland LAWTON CHILES Posie

WILLIAM 8. COHEN, Maine SAM NUNN, Goergn

DAVE DURENDERGER, Minneots JOHN GLENN, Ohio

WARIEN B RUDMAN, New Kampshire CARE LEVIN. Mrsigan

‘THAD COCHRAN, Masicipph ALBERT GORE, de "Tennesce

Prawns G, Po, Chief Counsel end Stef Disctor

Maxsanar P.Chiosiaw, Aovority Sif? reco

Suncomnirrrex ow Tyrancoventatenrat, Retanions

DAVE DURENBERGER, Minnesota, Chainnan

ITED STEVENS, Alaska LAWTON CHILES, Flere

THAD COCHRAN, Misisipp SAM NUNN, Geena

10m, Steff Dirwtor

‘Minority Stef? Director

‘Auove BM Grioano, Chi Clark

vl . bo F566

STKE

1 6g

; Gib

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL

US. Sexare,

‘Scnconomrrer oN IvreRGovERNMENTAT. RELATIONS,

Conmartae ON GovERNMENTAL AFFAIRS,

Washington, DC, May 1986.

Hon, Waa V. Rom, Jr.,

Chairman, Committee on Governmental Affairs, Washington, DC.

Dean Mr. Cuaman: I am herewith transmitting for printing as

4 conunittee print a study entitled “Congress and Pressure Grony

Lobbying in a Modern Democracy.” This study was done by

‘Congressional Research Service at my request as Chairman of the

Subcommittee on Intergovernmental Relations. I would like 10 ac,

knowledge, in particular, the assistance of Richard Sachs of the

Congressional Research Service, who served on detail to the sul.

‘committee during the course of oversight hearings on the 1946 Fed.

eral Regulation of Lobbying Act. Mr. Sachs is the principal author

of thie study with coutributions by Joseph Cantor and ‘Thomes

Neale of CRS,

Given the continuing interest in lobbying reform and campaign

finance, I believe this study will be useful as a committee print for

both Members of Congress and the Executive Branch

Dave Dursngencer,

Chairman, Subcommittee on International Relations.

Enclosure,

PREFACE

‘The part that interest groups and lobliyists play in shaping U.S.

public policy has been a subject for discussion and debate for over

two hundred years, It is an immense topic in terms of its historical

range: James Madiscn considered as.q matter of the first impor-

tance the question of balancing the selfish wishes of the “factions”

with what would be best for the new nation. Though more often

than not associated with its more shadowy aspects, lobbying is a re-

curring leitmotif in the drama of American politics; lobbyists are

prominent in the economic expansion of the new republic, in the

social movements of the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centur-

ies, and in the current era of economic redistribution. The subject

bears directly upon constitutional freedoms of petition, speech and

assembly, and the limits of these freedoms and the manner in

which they may be regulated. Political analysts and philosophers

have evolved complex theories of government and democracy itself,

based on relationshipe between intorest groups and goverament

Although pressure group activity in the Fedora agencies has in

greased in recent yecrs, Congress romains the primary target. In

it relationships with pressure groupe, Congrest rafts the com:

plex relationships of individuals and groups in society. Often, Con-

gress is both willing suitor and an unhappy victim of pressure

groups. Depending upon time, place and circumstance, it weleomes

the assistance that groups provide or it assails them for selfishness

and obstructionism. In its criticisms of pressure groups, it some-

times fails to distinguish between the process of group pressure and

what a group stands for.

To a degree, Congress controls the lobbyists. It prohibits some

groups from ‘lobbying entirely (certain tax-exempt, non-profit

groupe), allows a certain amount of lobbying by other groupe (cer-

tain tax-exempt, non-profit groups), and permits virtually unfet-

fered lobbying by a third large clasp of organizations. To differing

degrees, it controls the amount and type of lobbying that can be

done under a Federal contract by defense contractors, civilian con-

tractors and non-profit grantees. Congress statutorily prohibits the

use of appropriated funds for lobbying, but has difficulty drawing

the line at where information exchange ends and lobbying begins:

for example, it has traditionally provided office space for Pentagon

liaison offices, whose job in large part is to promote the Depart-

ment of Defense's legislative agenda. Congressional investigations

of alleged lobbyist improprieties or illegalities often place. Mem-

bers, themselves, at the center of attention, since they are the lob-

byiste’ target. Even in their ordinary, day-today relationships with

lobbyists, Members of Congress must make ethical and moral judg-

‘ments about the nature of special interest influence.

vw

Efforts by Congress to make lobbyists disclose some of their ac-

tivities have met with more failure than success. In this regard,

Congress must contend with two compelling and conflicting points

of view: first, that the Congress and the public are well-served by

the disclosure of private pressures on public issues, and second,

that almost all lobbying is constitutionally protected.

‘These efforts to require disclosure focus even more sharply the

complexities and conflicts of Congress-pressure group relationships.

‘The single omnibus disclosure statute—the 1946 Federal Regula-

tion of Lobbying Act (2 U.S.C. 261-270)—was substantially nar-

rowed by a 1954 Supreme Court. decision.! As a result of the

Court’s decision, present implementation of the act poorly reflects

the oxtent of lobbying i AWashington;, that is, many, who as

generally seem to be lobbyists are no longer required to regisler

under the law. To some, this is as it should be; the Court has pro-

tected the primacy of the individual’s right to petition. Over the

years, however, other Members of Congress have sought to provide

@ more accurate picture of lobbying pressures. Often, these efforts

for change have been precipitated by political scandal involving ac:

cusations of lobbyist im ies. At those times, congressional

investigations, have result in recommendations to expand the

law's coverage. Public sentiment in the aftermath of scandal has

often favc 2 broader law. In recent years, following the Water-

gate and Koreagate scandals, the House approved a new diccloaure

bill twice and the Senate once, but no law was enacted. After years

of debate and political controversy, Congress has yet to find a bal.

ance between the desirability of disclosure and the protection of

ithe complenly of Congres relations

complexity of pressure: p relationships, particu-

larly as reflected by. governmental. ‘offorts ‘to control lobbying, is

one theme of this report. Another is that Congress could continue

its efforts to strengthen the Lobbying Act

‘Chapter one reviews the history of lobbying in America, early ef-

forts by Congress to control lobbyists, and the debate over whether

interest groups are a positive or a harmful force in the American

governmental system; it also sketches some of the techniques that

comprise the job of the lobbyist.

Chapter two decribes the growth of lobbying in recent years, the

professional representation of increasingly diverse social and eco-

nomic interests, and the scope of regulations by which Congress

has sought lobbyist aecountability

Chapter three analyzes the 1946 Lobby Act, its origins in con-

gressional inve gations of lobbying in the 1930s, its swift passage

as part of the 1946 Legislative ‘ization Act, its diminish-

‘ment by the Supreme Court, and subsequent efforts to revitalize it.

Chapter four analyzes the major rationales for disclosure, includ-

ing the Supreme Court's determination in its 1954 decision and

current theories of pro-disloaure advocates, The chapter seeks to

determine. if there is a middle ground between First Amendment

rights and the need to .be informed about private ‘pressures on

"US Harry 841 US 61211960,

vu

Public policies where Congress could agree upon an effective for

of disclosure,

Chapter five atterapts a Jook into the future of lobbying and Con

gress pressure group relationships. It draws upon several views 0

the future of interest groups in society and questions whethe

lobby disclosure would have a role in the pressure group politics o

the future.

Chapter six concludes the report by offering a range of option

for congressional action. These options extend from repealing th

1946 Act entirely, through broadening the 1946 Act by mandatin,

criminally enforced disclosure requirements, to a system of volun

tary disclosure.

ie Primary source for this report is the hearings held by th

Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs on oversight of th

1946 Federal Regulstion of Lobbying Act, on November 15 and 16

19832 The hearings were significant for several reasons. First

unlike past hearings on this issue, these were not precipitated by

accusations of lobbyist impropriety, but by the committee's belie

that the issue of lobbyist disclosure could best be considered in ar

atmosphere of restraint and deliberation. Second, unlike most pas

inquiries, witnesses included not only affected parties, but expert

from the academic community and noted practitioners of the lobby

ing profession. Not since the broad investigations of a 1950 Hous

Select Committee on Lobbying—informally called the Buchanat

Committee after Chairman Frank Buchanan of Pennsylvania—ha

the issue recvived such a comprehensive review.” Thitd, the hear

{nga i not focus on one bill of 1, but sought to accumulate

4 body of information from which futuré proposals could be devel

In addition to congressional and other ‘public documents, the

report relies on works from the disciplines of political science, soc!

ology and political story. In diseusing fhe history of lobby dele

sure, this paper relies particularly on study prepared for the 197

Commission on the Operation of the Senate.*

2S, Congo, Senate, Commitee on Governmental Afr. Overight of the 1948 Fader

Regulation of Labytog At Hsaringy, Bah inet, 1082 Washington, US, Gov

Pet Of 06d 5 pore ched we 186 Eaby Hoornge ee

ra cores, rum, Sues Crmltae on Uv Avi The ol of tabring

Repreentalle Ss Goveroment. Hearings Sit Congres Ss ton ash Waance

Gop Beit Om 860 Ut p Grater Sed au 1900 Buchan Hearse) -

US. Congress Sate. Cnniion ae the Operation ofthe Senate Senators OMe, Ethic,

nd Pree lace Prt, th Congres, Bd soion, 1577 Washingion, US. Gove Brn

‘say

‘Com

(tt, 1p 150192 Horner, cited su 077 Commence

You might also like

- Information SessionDocument2 pagesInformation SessionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

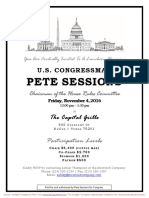

- LuncheonDocument4 pagesLuncheonSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- Luncheon For Republican Governors AssociationDocument2 pagesLuncheon For Republican Governors AssociationSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- ReceptionDocument2 pagesReceptionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- Birthday CelebrationDocument3 pagesBirthday CelebrationSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- LuncheonDocument2 pagesLuncheonSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- FundraiserDocument2 pagesFundraiserSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- ReceptionDocument2 pagesReceptionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- LuncheonDocument2 pagesLuncheonSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- Private Screening of Jason Bourne For Pete SessionsDocument2 pagesPrivate Screening of Jason Bourne For Pete SessionsSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- FundraiserDocument1 pageFundraiserSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- FundraiserDocument2 pagesFundraiserSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- LuncheonDocument2 pagesLuncheonSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- LuncheonDocument2 pagesLuncheonSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

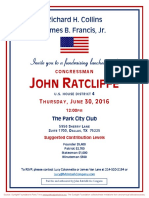

- Reception For John RatcliffeDocument1 pageReception For John RatcliffeSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- ReceptionDocument2 pagesReceptionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- FundraiserDocument2 pagesFundraiserSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- ReceptionDocument2 pagesReceptionSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)