Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Card I Fiction Es

Uploaded by

wax00r100%(4)100% found this document useful (4 votes)

1K views73 pagesCardifictiones

Original Title

Card i Fiction Es

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCardifictiones

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

100%(4)100% found this document useful (4 votes)

1K views73 pagesCard I Fiction Es

Uploaded by

wax00rCardifictiones

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 73

Contents

Introduction

Finger Flicker

Master of the Mess.

Method and Style and The Performing Mode . . .

Colour Sense

High Noon.

Cincinnati Pit ae

Inducing Challenges

Triple Countdown .

Unforgettable

‘Acknowledgements

lastWord

Bibliography.

Introduction

Imagine

You sense the colours of playing cards through a solid table.

You stack four Poker hands in less than ten seconds.

You kick any named number of cards off a tabled deck.

You put chaos to order.

You magically move cards to any positions in the pack at will.

You transpose a card from between a spectator's hands to under his watch.

You instantly memorize the order of a shuffled deck.

This booklet will not enable you to do any of those things. Most of them are, after

all, impossible. Fortunately, however, we can make our spectators experience these

impossibilities anyway. We do that by creating fictions, In this case Card Fictions.

It may sound obvious, but it is this simple realization that makes magic as a perfor-

ming art possible in the first place: Evoking the feeling of impossibility does not

require actually doing the impossible. However, it will always require a team-effort.

‘A fiction is created in somebody's mind. Equipped with those marvels called human

perception and the human mind our spectators play a necessary and active part in

the process. All that we performers do is to provide adequate input. Then we lean

back and relax as the spectators themselves spontaneously and effortlessly complete

the job and create fascinating, impossible ~ magical ~ fictions.

The tricky part is: What exactly is “adequate input”? This booklet tries to answer

that question. Its clear intention is not only to provide descriptions of bare technical

procedure, but also to address some of the other elements that contribute to the

creation of the seven Card Fictions sketched above.

Throughout the text you will find thoughts on topics as diverse as the function of ma-

gic gestures, the setting of mnemonic anchors, using ambiguous wording, “believing”

in your own magical powers and many more. Those tools ate at least as important for

the creation of convincing magical fictions as palms, shifts and forcing decks.

In two cases either no suitable way was found to include the discussion of such

a strategy into the explanation of a specific trick, or the topic was considered too

substantial to be discussed en passant. As a result you will find two short essays.

Finally, about the tricks themselves: There were two criteria for the inclusion of

material in this booklet, one concerning method, the other, effect. First, every

routine can be done with a regular deck. Second, the tricks cover quite a variety

of phenomena and plots: From a demonstration of “colour-sense” to cheating at

gambling, from supposedly superhuman speed to incredible memory and from

impressive skill to downright impossibilities.

It's time to get started: Grab a deck, turn the page and enjoy the ride! I wish you and

your spectators a wonderful time whenever you play together again to create magical

Card Fictions.

Pit Hartling

Frankfurt, June 2003

Finger Flicker

Effect

A deck of cards is shuffled, squared and

placed onto the table. Somebody names

a number. With a “flick” of just one

finger, the performer kicks exactly that

number of cards off the tabled deck.

The deck is shuffled again and another

number is nated. A spectator covers

the performer's eyes with her hands.

Blindfolded like this, the performer

again kicks off a packet with one finger.

The spectator counts and once more

the absolute precision of the flick is

confirmed.

For a final demonstration, a card is selec-

ted and shuffled back into the deck by

a spectator. Aiter briefly riffling through

the cards, the performer places the deck

squarely onto the table. The selection is

named. Remembering its position in the

shuffled pack the performer “flicks”

directly to the named card!

Method Overview

This makes somewhat unorthodox use

of the breather crimp '. With such a

crimp in the deck, it becomes possible

to “flick off” exactly all the cards

above it.

Set-Up

Put a breather crimp into the King of

Hearts. For this routine, the card is held

face-up as the work is applied (Photo 1).

1 A breather crimp is put into a card by pinching the card between the thumb {above} and second and third finger

{below} at one corner, squeezing rather tightly and pulling the fingers actoss zo the diagonally opposite comer. This

process is repeated along the other diagonal, resulting in a crosswise crimp. A very good descrigtion can be found in

the fist volume of the "Vernon Chtonicies": Minch, Stephen, The Lost Inner Secrets, Vol. , “The Breather Crimp”,

pp, 96., 1987, Lal Publishing.

10

That way, the resulting slight bump will

be towards the back of the card. When

the deck is cut face-down, the crimped

King will be the top (face-down) card

of the lower half of the deck. To facili-

tate locating the crimped card in the

squared deck it is also edge marked.

For impromptu use, a nail nick will

do just fine, To perform, position the

crimped card eighteenth from the top

of the deck.

The “Flick”

Place your right hand in front of the

deck, your first finger almost touching

the deck’s inner long side (Photo 2). By

kicking the first finger against the edge

of the cards and upwards, you can cut

off part of the deck: The top packet will

turn face-up and land in front of the

bottom half (Photo 3), With a minimum

of practice, you will be able to flick off

exactly all cards above the crimp.

Performance

I - THE FLICK

Positioning the crimp

Start with seventeen cards above the

crimp. You will have somebody name

a number between ten and twenty.

During a short shuffle, the crimp is

positioned to end with exactly the

named number of cards above it.

Here’s the procedure:

Hold the deck in the right hand in posi-

tion for an overhand-shuffle. Start this

shuffle by taking a block of at least eigh-

teen cards with the left thumb. Run the

next card singly, injogging it in the

process, and shuffle off the rest of the

deck. Take a break under the injog and

start shuffling off to the break. As you

start this second shuffle, ask a spectator

to name a number between ten and

twenty. Time this request in a way that

she answers before your shuffle reaches

the break. {Of course, you can always

imperceptibly slow down the shuffle in

case it takes her unusually long to

decide on a number}.

There were seventeen cards above the

crimp, so if she names that number, just

throw to the break and then throw the

remaining packet on top. You have, in

effect, done a simple jogshuffle, keeping

the crimped card in place.

Ifa lower number is named, subtract

that number from seventeen. Throw

to the break, run the necessary small

number of cards and then throw the

remaining packet on top. For example,

if she names fourteen, throw to the

break, run three cards and throw the

rest on top. There will be fourteen cards

left above the crimp.

If eighteen or nineteen is named, do not

throw to the break, but instead stop the

shuffle with one, respectively two cards

still on top of the packet before thro

wing it on top. Either way, you end with

the named number of cards above the

crimp.

Place the deck onto the table in front of

you with a long side parallel to the table

edge in position for the “Flick”. Get

ready with your hand in front of the

deck. After a short dramatic pause, kick

off all the cards above the crimp with

your right first finger. Very clearly and

slowly count those cards to show you

actually flicked off exactly the correct

number.

Il - THE REPEAT

Once the premise is clear, Finger Flicker

cries for a repeat. For this, position the

crimp twenty-eighth from the top. There

are several ways to achieve this: You

might run the required number of cards

on top during an overhand shuffle. Or

do a faro shuffle followed by running

a few single cards.

Have a spectator name another number,

this time between twenty and thirty,

and repeat the above jogshuffle-handling

exactly as before to end with the named

number of cards above the crimp.

In order to have some progression, four

things are different this second time:

First, you ask for a higher number. Even

though this doesn’t make much

difference, emotionally, it might seem

more interesting. Also, counting to a

higher number will take just a little bit

longer, leaving a bit more time for some

tension to build. Second, announce you

will do the “Flick” with your left hand.

With a little bit of practice you will find

that this hardly makes any difference.

Third, before you flick off the packet,

have a spectator stand behind you and

cover your eyes with her hands: Not

only do you repeat the stunt left-han

ded, but also “blindfolded” (Photo 4).

To the spectators, this seems almost

otherworldly.2. Finally, instead of coun-

ting the cards yourself as you did before,

have a spectator pick up the flicked-off

packet and clearly instruct her to count

the cards onto the table one by one.

This handling adds an element of

openness and fairness that really

helps to “sell” the repeat.

Il — FINALE!

For the finale, have a card selected for-

cing the crimped King of Hearts. Have

the spectator replace her selection and

thoroughly shuffle the deck. Retrieve

the cards and, if necessary, cut to leave

the breather near the centre, (You can

tell the card’s position by glancing at the

edge of the deck.)

Pause a beat and without comment riffle

up the inner end of the deck pretending

to remember the order as the cards fly

by. In fact, remember the card above the

selection. Have the spectator name her

card. She will, of course, name the King.

of Hearts. Concentrate and say, almost

to yourself, “King of Hearts..., ah yes:

next to the Nine of Clubs”, naming the

card you just remembered. After a suit-

able dramatic pause, do the “Flick”. The

card that comes into view on the face

of the cut-off packet is the card you

mentioned.

2 This strong dramatization can be found in Darwin Ortiz’ wonderful book “Cardshark": Ortiz, Darwin, Cardshark,

“Blind Aces, pp-06, USA 1005.

Dramatically turn over the next card,

the King of Hearts. Climax! (Photo 5)

Credits and Comments

Finger Flicker bears some resemblance

to the classic salt-location. In that trick,

some grains of salt are secretly transfer-

red to the back of a selected card.

Traditionally, the deck is then placed

on the floor and slightly kicked with the

foot, causing the deck to slide open

exactly at the selection. Two versions

of that can be found in John Scarne’s

Scarne on Card Tricks: “Hands-Off

Miracle”, pp.61 and “The Spirit Card

Trick”, pp.237, USA 1950.

A version of the above that uses a crimp

instead of salt is Harry Lorayne’s

“Salt-Less” from Close-Up Card Magic

{Lorayne, Harry, Close-Up Card Magic,

“Salt Less”, pp.31, Tannen Magic Inc,

New York, 1976)

The method to position of the named

number of cards above the crimp using

an overhand shuffle (also used in Triple

Countdown page 68) was inspired by a

force I came across in Annemann’s use-

ful compilation (Annemann, Theodore,

“202 Methods Of Forcing”,

Max Holden, New York, 1933).

lonly added the Jog Shuffle.

The Ambidextrous “Flick”

For this idea you need an additional

deck in memorized order. This deck

also contains a breather. After having

a number named position the breather

in the shuffled deck as described. Have

a second spectator name another num-

ber from one to fifty-two. As the second

deck is in memorized order, it is an

easy matter to position the crimped card

under the named number of cards. Place

both decks in front of you in position for

the “Flick”. Hold out both first fingers

and after a short pause, cross your arms

(Photo 6). Do the “Flick” with both

decks simultaneously. Have both specta

tors pick up the flicked-off packets and

count the cards in sync. After the first

number is reached and verified, have

the second spectator continue. You

flicked off exactly the named number

of cards in both decks!

Master of the Mess

Effects

‘The performer challenges himself to

perform something with the deck in a

complete mess: All fifty-two cards are

splashed onto the table and thrown all

over the place, forming a haphazard

mix of face-up and face-down cards.

The audience concentrates on one card.

Without asking a single question the

performer removes one card after the

other from the big heap, gradually elimi-

nating all but a single card. Incredibly,

he managed to pinpoint the selection!

A new card is selected and lost in the

mess. The performer carefully squeezes

the deck at the fingertips. At his touch,

chaos turns into order: Every card lies

face-down again - except the selection!

Comments

The two tricks are methodologically

linked. The first effect contains a large

part of the second effect’s method. If

you can make your spectators perceive

the two as separate and independent,

you will have two strong pieces of

magic. If not, I am afraid the result

will be an ugly Faro-Monster.

As they share the plot of returning chaos

to order, Master of the Mess could be

1 Vernon, Dai, “Trlumph”, Stars of Magic, pp.23, USA,

considered a handling of “Triumph” '.

In Dai Vernon’s incredible classic, how-

ever, chaos is produced in quite a clean

way by neatly riffle-shuffling two packets

together. Here the image of chaos is

much more memorable, giving the effect

a somewhat different feel.

Method-Overview

The deck starts in a random mix of

face-up and face-down cards. For the

first effect, one card is forced. During

the gradual elimination, the cards are

secretly arranged into a certain face-up/

face-down sequence. The faro shuffle is

then used to group together all face-up

cards. Once together they are turned

over as a block straightening the deck.

Set-Up

Use a complete deck of fifty-two cards

in good condition.

Performance

Prologue

“Sometimes, to surprise myself, 1 do

something in a very different way than

usual. Recently, I wondered whether I

could still perform magic with the deck

in a complete mess, like this...”

Chaos

Tur about half the deck face-up and faro-

shuffle this packet into the face-down rest

As true for so many of the concepts mentioned in this booklet, ! have learned much about mnemonic anchors

from Juan Tamari2, Discussion and applications ofthe principle also can be found throughout the work of Arturo

de Ascanio and Roberto Giobbl, among others.

of the deck without pushing the halves

together yet. The shuffle does not have

to be perfect; for now it just serves to fa-

miliarize the audience with this unusual

handling. Place the deck onto the table

in its incomplete-faro condition and give

it a twist, letting the cards spin on each

other (Photo 1). This little flourish is a

pretty and rather unusual sight - qualities

that make it a very memorable “anchor”:

When the same handling is used again

later in a very different situation, it will

serve to bring back the image of chaos

it has been associated with. This can be

reinforced by always referring to this

handling as the “Chaos Shuffle” *. Keep

turning and twisting everything and

spread out the deck until the cards are

distributed haphazardly across the table

in a complete mess. Have two or three

spectators join in, mixing everything

around with both hands (Photo 2}.

Throw big lumps of cards into the air,

letting them scatter all across the

table (Photo 3). Take your time here;

this clear and extremely memorable

picture of utter chaos is the routine’s

main benefit. You will have to pay a

price for it in a second, so make sure

to get the most out of it now.

1- DIVINATION

The first effect is the divination of a

card, It uses a dramatization that almost

automatically generates interest and

suspense.

The selection

Push the cards together in one big

heap and square the deck. You will find

it easy to end up with the bottom card

of the deck face-down. Look at and

remember this card. Let’s say it’s the

Eight of Hearts, You will now force

a

this card with a peek force: With the

right hand swing cut about half the deck

into the left hand. A second before com-

pleting the cut, pull the top card of the

left hand packet a little towards yourself

with your left thumb (Photo 4). Drop

the right hand half on top and push the

protruding card into the deck until it

remains injogged only a fraction of an

inch. The Eight of Hearts should be

directly above this injog. Hold the deck

in the left hand at the lower left corner,

ready for a fingertip peek. Run your

right first finger across the upper right

corner of the deck and ask a spectator

sitting directly opposite you to say

stop. Timing your riffle with her words,

stop at the position marked by the injog

{you will feel a slight “click”). Show

the card to the spectator and ask her

to remember it (Photo 5) >.

Briefly repeat the “Chaos Shuffle”

pushing the cards together as in a faro

and giving the telescoped deck a twist

on the table exactly as before. Again,

let the cards spread out and cover a big

space. The selection should fall face-up

and be clearly exposed.

Suddenly, it occurs to you that it would

be better if everybody knew the card.

Announce that you will turn your back

and if the spectator can see her card in

the mess, she is to point to it silently to

inform the others. In case she does not

see her card, you add, she doesn’t have

to search for it but simply point to any

other card and everybody thinks of that

one instead. This last statement is, of

course, a pure bluff: You know she can

see her selection (make sure she does)

and she will point to it. In a way, this

handling is similar to pre-show work:

You will find a “super practice” shot ofthis fingertip peek force on the Flicking Fingers’ DVD “The Movie”. Many

more Fingertip-Peek handlings can be found in Ed Mario's booklet on the subject (Marlo, Ed, “Fingertip Control",

Chicago, 1956)

The real selection-process (the peek

force} is not given much importance.

In contrast, the image of the spectator

silently pointing to a card while the

performer has turned his back is much

more memorable. Later some spectators

might have forgotten about the peek,

being left with the impression that a

card was agreed on by a spectator simp-

ly pointing to any card she wanted *.

Face your audience again and immedia-

tely shuffle everything around, turning

over several lumps of indifferent cards

‘if you do not feel confident with this kind of strategy, @ good way to insure success is to turn your back, wait a second

and make the additional comment only when you know she has already pointed to her original selection. Given a

‘minimum of spectatormanagement and acting however, you will ind this safety measure hardly necessary.

(the selection is left face-up). The card

they have in mind clearly seems to be

any one of fifty-two.

Elimination

Explain that under these conditions,

with the deck chaos-shuffled before and

after and by the spectators themselves,

it is very difficult to pinpoint the one

single card they have in mind. So, you

are using a process of “intuitive elimina-

tion”. Hesitatingly start removing cards

from the centre and dropping them to

the side. You remove face-up cards and

face-down cards, singly and in small

groups, discarding them onto a pile

(Photo 6). All the time avoid the Eight

of Hearts.

After you have eliminated about half the

deck, pause and remix the remaining

cards. Again, turn over some of the

cards, this time including the selection.

Keep a finger on that card as you mix

everything around and finally end with

the face-down selection at a known po-

sition on the table. Like this, during the

last part of the elimination-procedure,

the selection is nowhere to be seen and

the spectators are left in doubt as to the

trick’s success. Continue eliminating

indifferent cards until you are down to

the last five.

Turn all five remaining cards face-up in

a line with the selection second from

the right. The spectators see that the

23

selection is still there. For some this

might be a relief, others might have

secretly hoped to see you get into

trouble. Whatever their feelings, they

will now make an emotional U-Turn:

Take the card from the right end of the

Tow and use it to scoop up the thought-

of Eight of Hearts. Turning your wrist,

turn both cards face-down and appa-

rently place the Eight onto the discards

face-down. In fact, push the indifferent

card from the back of the two onto the

discards and immediately place the

Eight back face-down to the right end

of the row. Apparently, you have just

eliminated the selection! Without pau-

sing take the next card with the right

hand and clearly throw it onto the

discards face-down, following by using

the next card to scoop up the last and

eliminating these two face-down as well.

As you do all that in an unhurried but

flowing rhythm, say: “It’s not the Eight,

not the Ten, and none of these two

either!”

Square the discard pile and take the

deck in dealing position. One single

card is left on the table. Confidently

ask which card they have been thinking

of. When they tell you, appear irritated,

look at the deck, back to the spectators

and after suitable build-up finally turn

the card on the table face-up to reveal

the selection!

Under the surface

Even though it is a rather strong piece

of magic in its own right, there is more

to this effect than meets the spectators’

eyes. Specifically, the elimination of

cards is not quite as random as it

appears. Here’s what really happens:

As you remove cards and throw them

onto the discard pile, you build the

sequence shown in (Photo 7). If at first

sight this looks pretty mixed, that’s

good. On closer inspection, however,

it can easily be seen that the face-up/

face-down pattern follows the formula:

22 121

| SSR sesSutcatesnesoatueiasscatncisasssnsstnatstnesicarstnsszcusssnasscerstnassetnasnassetnasasbssinatstssicetstezsiceassastserstactateetiactateetaietetastateietsetaieiataeiin,

That is, the cards alternate face-up/

face-down in groups of 2 cards, 2 cards,

1 card, 2 cards, 1 card, and so on. The

sequence is symmetrical, so it doesn’t

matter which side of the deck is up.

Arranging the cards

When removing cards to form the

sequence it helps to think in groups of

four, Alternate between saying to your

self “2 2” and “1 2 1”. That is, the first

group is two cards face-down, then two

cards face-up. The next group is one

face-down, two face-up and another one

face-down. Next comes two face-up and

two face-down (the opposite of the first

four). Always alternate between face-up

and face-down, taking groups of

22,121, 22, 121, ete.

Your attention should be on the cards in

the middle of the table and on the spec-

tators. The discard pile is just that:

‘Those cards are out of play and of no

importance anymore. This impression is

enhanced by leaning somewhat to one

side, establishing this part of the table

as centre stage. Building the discard

pile on the other side all but makes it

disappear in the shadow zone.

The first few times you try arranging the

cards as described your rhythm will

probably be less than perfect. If you

practice this pick-up stack a few times,

however, it will soon become quite easy.

When you are familiar with it, you will be

openly arranging a whole deck of cards

right under your spectators’ noses (in fact

inviting them to watch) without anybody

being aware of what they are looking at.

Il - FROM CHAOS TO ORDER

If you followed the description exactly

as described, the top few cards of the

deck will be not quite in sequence: The

last cards you removed were all placed

onto the discards face-down. This is cor-

rected quite openly near the end of the

effect: When the spectator names the

selection you are slightly taken aback.

Apparently, you have eliminated this

card a second ago. Hesitatingly look

through the top few cards of the deck.

As you do that, openly turn the top card

and the fourth card from the top face-

up. The selection is still on the table, so

one card is missing at the beginning of

the sequence, but other than that the

deck is now in perfect 22121 order.

For the spectators, the trick has just

finished. The selection has made its

surprise-appearance, and in the best

of all worlds, the built-up tension and

the apparent mistake at the end should

trigger laughter and applause. This

relaxation is used to cover the first faro:

Just before the applause reaches its peak

and with the selection still face-up in

the middle of the table, calmly give the

deck one straddle faro by cutting off 25

cards and shuffling them into the remai-

ning 26. (For easy orientation: In this

routine all cuts to the centre in prepara-

tion for a faro shuffle are between two

face to face cards).

Still chaos

Unhurriedly give the deck a second

faro, this time without pushing the

halves together. Instead, place the selec-

tion on top of the deck face-down (!)

24

ee

and repeat the “Chaos Shuffle”: Place

the deck onto the table in its incomplete

faro position and carefully give the con-

figuration a twist as described. You will

find that you can spread-out the deck

surprisingly far without any card chan-

ging position (Photo 8). Although this

time the shuffle is a perfect faro and the

cards do not really get mixed around,

the handling looks very similar to the

actual random version established twice

before. It should strongly confirm the

spectators’ belief that the deck is still

a complete mess.

Give the spectators all the time they

need to talk about the previous effect,

wait, have a drink and enjoy yourself.

To resume your performance, square the

apparent mess at great length and hold

the deck in right hand Biddle grip. The

top card should be face-down. Dribble

the cards into your left hand and ask

a spectator to call out stop. There is a

small group of face-down cards just

above centre. When he calls out stop,

stop anywhere in that group (the timing

is not overly difficult], With your left

thumb, push the card he stopped you

towards the right and raise your left

hand, giving the spectator a good look

at his selection. Ask him to remember

the card. Replace the top half, holding

a break above the selection.

You will now exchange the selection

with the top card of the deck: Hold the

cards in position for an overhand shuf-

fle, taking over the break with the right

thumb. To start the shuffle, peel off

only the top card with the left hand.

On top of it throw all cards above the

break. Again run one single card (this

is the selection). Continue running a

small number of single cards, say five.

Then throw the rest of the deck on top

slightly outjogged. Start a second shuffle

by taking the top half with the left hand.

On top of it, run the same five single

cards and finish by throwing the rest on

top. Finally turn the whole deck over

(the selection ends face-up on the four distinct sections (Photo 10). One

bottom of the deck). more faro would separate the face-up |

from the face-down cards. There is,

Openly give the deck one last out faro. however, a shortcut:

Letting the cards “sink” together, in-

stead of springing them gives the shuffle Aided by the natural breaks, take out

a somewhat sloppy touch that fits quite the centre block of twenty-six cards

‘well at this point (Photo 9). The four with your right hand and place it

quarters of the deck now alternate ‘on top of the deck, keeping a break

face-up and face-down. If you look at between the other two quarters as

the edge of the deck you should see

they coalesce (Photo 11), Follow

26

by cutting the deck at that break,

bringing the bottom quarter to the top.

The face-up and face-down cards are

separate, All that remains is secretly

to reverse the bottom half of the deck.

A half pass could be used, but | usually

simply reverse the half more or less

openly as part of a short display after

the cuts.

Magic

Briefly remind your spectators of all the

crazy shuffling and mixing. To them,

everything is still a hopeless face up/

face down chaos and the selection is

lost anywhere in that mess. To make

the magic happen, hold the deck at the

fingertips and very delicately and ever

so slowly square the edges (Photo 12).

Dramatically crack the deck between Bare Bones {

your fingers (Photo 13). At first glance, this description might {

read like a course in quantum physics.

Very slowly spread the deck on the To make the routine easier to follow,

table. Card after card comes in sight here’s the procedure again step by step: i

face-down, giving the spectators time \

fully to appreciate what happened Chaos

before one single face-up card appears - Real face-up/face-down shuffe, faro-style.

near the right end of the spread: the - Twisting of telescoped deck.

selection! (Photo 14). (“Chaos Shuffle”)

- Complete mess

28

2

First effect: Divination

- Peek-force. Spectator points to her card

in the mess.

- “Chaos Shuffle” again

- Elimination of cards. Forming of

22121-sequence in discard-pile.

- More mixing, selection turned

face-down. Further elimination

down to the last five cards.

- Apparent elimination of selection and

surprise appearance. Climax!

- Faro shuffle during spectators reaction.

- Selection is placed on top of deck

face-down

- Second faro and twist-flourish-handling

that simulates established

“Chaos Shuffle”

- Pause. Deck ieft spread-out on table.

Apparently still complete mess.

Second effect: Order

- Dribble to have card selected from

small face-down block above center.

Break above selection.

- Short overhand shuffle to exchange

selection with top card of the deck.

- Turn deck over

- Third faro, letting cards “sink”

together.

- Cuts in hands, completing separation

of face-up and face-down cards.

- Turnover of bottom half

- Magic Moment

- Slow and wide Spread. Climax!

Credits and Comments

Although the basic idea for Master of

the Mess has mysteriously popped into

my head from wherever it is that those

things pop into our heads from, it was

not surprising to find that others had

the same thing happen to them long

before me, Even less surprising is the

fact that one of those others was

Ed Marlo. I hereby officially suggest

anice trophy to be given to any card

worker who has never accidentally

reinvented a Marlo-idea. (Johann.

Hofzinser comes to mind but recent

historical studies have given cause for

serious doubt). The entry in question is

named “76-76-67-67” and can be found

in Marlo, Ed, Faro Notes, Chicago,

1958, p.29.

The second great collegue [ had the

honour to share some neuronal firing

with is Camilo Vézquez from Madrid

(jHola Don Camilo). His effect

“Un Gran Triunfo” uses the same basic

idea of grouping together reversed cards

with the faro-shuffle. It can be found in

Juan Tamariz’ seminal work on memo-

rized deck magic. (Tamariz, Juan,

Sinfonfa En Mneménica Mayor Vol I,

Madrid, 2000, p.176).

As Dai Vernon has already been mentioned

in the introductory comments and mentio-

ning Dai Vernon one more time would be

redundant I shall not mention Dai Vernon

again.

Master of the Mess went through quite

anumber of different versions. | want

to thank Denis Behr for his invaluable

input during every stage of the routine’s

evolution.

Method and Style aw

The Performing Mode

On Method and Style

In addition to the many different styles of presentation, there are also different

styles of method. Over the last few decades, the technical repertoire of Card Magic

has evolved quite rapidly: Where only a century ago, performers had a more limited

number of moves and strategies at their disposal, we can now choose from literally

thousands of sleights and principles to reach our magical goals. With this liberty

comes the burden of choice. In magic, one effect can often be reached by a multi-

tude of methods. Theorists have long been looking for criteria that would allow

clearly saying which methods are “better” than others. Even though there might

actually be a few such criteria, sooner or later, somebody will come along, break all

the carefully established rules, do everything “wrong” and the result will be not only

deceptive but also beautiful, artistic and highly individual.

There are two points to this: First, what might be a highly deceptive method for one

performer might not fool a five-year old when done by somebody else. And second,

the more experienced we become, the more we know and the more methods we

assimilate, the more personal our choices will be and the more these choices will be

part of whatever it is that constitutes our style. Given a certain minimum of artistic

experience, there is no “good” or “bad” anymore, “Right” and “wrong” have been

replaced by “you” and “me”.

In practice, this can be seen constantly: How would you personally approach the

effect of a shuffled deck being magically put into New-Deck order? Are you part of

the deck switch-faction or do you consider yourself a member of the false shuffle-

club? Or how about mind reading: Would you opt for a force followed by a clean

divination? Or would you choose a higher degree of freedom of choice, followed by

some fishing? Of course, these decisions may be influenced by many factors like

performing situation, practicality, technical ability, etc. But ultimately, those choices

will be the result of -and at the same time a constitutive element of- your own

personal style.

That said I want to mention a certain methodological tool that might or might not

fit your style. The concept is not mine; in fact I think nobody can claim having

“invented” it and I am sure many of you are already using it to a certain degree

without even realizing it. At least, this is what happened to me: Even though I had

been using the strategy quite a bit, I was hardly aware of the fact (and certainly did

not consider it a “concept”) until I came across an eye-opening article Rafael Benatar

30

published in MAGIC Magazine in January 2001. As the psychological technique

that Rafael described in his article is quite an important element of my performances

I felt some of the descriptions in this booklet could be more deeply understood if this

was explicitly addressed. So, with Rafael Benatar's friendly permission, and under his

excellent title, let me offer a few thoughts on:

The Performing Mode

In most silent performances of stage magic, almost every move the performer makes,

every gesture and every gaze are seen as part of the performance. The “act” is just

that: A carefully studied sequence of actions that runs like a clockwork. That is part

of its beauty.

The unique quality of a typical close-up performance on the other hand is a much

higher degree of interaction between the performer and the spectators: Before and

after the performance of individual tricks people ask questions, tell little stories,

joke, laugh and talk about what they have seen, During these moments there is no

“performance”. it’s like an intermission between acts. After a while, the performer

strikes the gong, everybody re-enters the theatre and the performance is resumed

“Striking the gong” is switching back to Performing Mode and it is clearly marked

by a change of attitude: The performer sits up straight, pulls back his sleeves and

gets ready for the next effect. The spectators focus on the performer again, clear

their minds, stop talking and lean in to watch whatever miracles are awaiting them

next. All of this is well known and I guess there are few close-up performers who

have never set-up some cards in preparation for the next effect while “toying with

the deck”. What opens up a whole area of possibilities is the realization that we can

create those “intermissions” almost at will not only before and after but also during

the course of a trick, This allows us to do all sorts of method-related business quite

openly without it being perceived as part of the show.

A good illustration of the principle is the following gag: You bet a friend that you

have full control over his body. You claim you can make him move at your command

and that he will have no chance whatsoever to resist your powers. To prove your

point, suggest you will make him turn over his hand against his will and without

touching him. When he agrees officially start the demonstration: Hold out your

hands horizontally, and carefully position one above the other a few inches apart

with the palms “facing” each other. Take your time, as if everything had to be

adjusted just right. Have him place his hand flat between yours. As soon as he does

so, add: “No, the other way round”. He turns over his hand and - Tadaaa! - you have

made your point!

This gag is not as silly as it seems. Think about it: You tell your friend you are going

to make him turn over his hand. He tries to work against you. Yet, one second later

‘he voluntarily turns over his hand. Why does this work? It works because he did

not take your instruction to turn over his hand as part of the test; for him, the actual

demonstration had not yet started. This is remarkable: Even though you have offici-

ally announced the performance to begin just a second ago, just with a slight change

of attitude and slightly different inflection of your voice you have made him perceive

the crucial instruction as an irrelevant formality.

There's one difference to this gag-example and the application of this principle to

magic: In the above gag your friend will realize what happened as soon as you say

“Tadaaa”. In magic, instead of revealing that your spectators misjudged the impor-

tance of a certain moment, you confirm their (mistaken) intuition that the little

spontaneous “intermission” really was just that by officially switching back to

Performing Mode and officially resuming the performance.

In short: By changing the inflection of your voice, your posture and your overall

attitude it is possible to put actions “in parenthesis”, to make certain moments

during your performance seem unplanned, and not part of the show. Your spectators

will still see what you are doing (just like your friend heard you say “no, the other

way round”) but done correctly, they will tend to dismiss those moments as unim-

portant asides and forget about them the moment you “switch back” and continue

the show. Unlike in “misdirection”, you don’t try to hide anything or make anybody

look elsewhere; you are happy to have your spectators watch everything you do,

assuring that it is perceived as nothing of importance and forgotten a second later.

Using this idea of planting a few “mini-intermissions” in your performance is a

double-edged sword: On one hand it allows you to make some “tricky” actions pass

more or less unperceived without leaving your spectators with the feeling of having

been “misdirected” or having missed anything. On the other hand it interrupts the

flow of your show. The more often you apparently leave Performing Mode, the more

spontaneous, unplanned and “loose” your performance will appear. That might ot

might not suit you very well, depending on your style. I for one believe when

Dai Vernon talked about clarity of effect he was right in saying “Confusion is not

magic”. When talking about method, however, I tend to add “...but it helps”.

The next trick shows the concept of “Performing Mode” in action.

32

Colour-Sense

Effect

A deck of cards is thoroughly shuffled

by a spectator. He takes a packet and

holds it under the table face-up. The

performer touches the table surface

with his palm directly above the hidden

packet and feels for the colours. One

by one he actually names the colour of

each and every card before the spectator

places it onto the table. The performer

can identify picture cards, tell the num-

ber of cards in the packet and finally

even sense the exact suit and value.

Method Overview

When the shuffled deck is retrieved,

the performer briefly spreads the cards

from hand to hand and memorizes the

colours of the first thirteen cards. The

deck is roughly divided into quarters

and the memorized packet “forced” on

a spectator to be taken under the table.

Performance

Prologue

Have somebody thoroughly shuffle the

deck. Meanwhile, introduce the pheno-

menon, preferably starting with a strong

and fascinating statement: “At the mo-

ment I practice seeing through walls.

I have only just begun and it’s more

feeling than actually seeing, but I can

already make out shadowy outlines and

even slight hints of colour. It’s actually

quite nice”. Spontaneously offer to show

whatever progress you already made by

using the table instead of a wall and

retrieve the deck. You will now

memorize the coloursequence of the

first thirteen cards from the face.

Lewis Jones’ “Pattern Principle”

There are but a few practical ways to

memorize the colours of a sequence

of cards. One is to look at the size of

colour-groups. That is, if there are three

red cards, followed by one black, two

red, five black and finally one more card

of each colour, you’d translate this to

312511, remembering it like a phone

number (three, twelve, five, eleven).

Another method was published by

Karl Fulves in 1998 under the title of

“Combo”. Unfortunately, | am not at

liberty to explain it here. 1 do recom-

mend you check out his original

manuscript.

Finally, an ingenious and wonderfully

practical method is Lewis Jones’

“Pattern Principle”. Briefly (and with

Mr, Jones’ friendly permission): You

mentally divide the sequence in triplets.

‘There are eight possible red/black

combinations for a group of three cards.

Every one of these eight possibilities is

given a unique and easily remembered

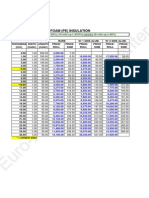

name. Photo | shows the eight possible

triplets with their labels (The labels are

easily remembered, when you take the

colour red as orientation)

For example, the twelve-card sequence

RBB BRR BRB RRR translates

into “Bottom/ Upper/ Middle/ All”.

a7

Lewis Jones’

Pattern Principle

This is condensed even further by

remembering only the first letter of each

triplet, forming a short word that is easy

to remember. (In our example this word

would be BUMA). If the first letters do

not form an easily remembered expres-

sion, simply insert an extra i or e. Thus,

UMITN becomes UMTIN or MBLT beco-

mes MiBLeT, Amazing as it may seem,

remembering only two of those words

you have securely stored the colour

sequence of twenty-four cards; about

twice as many as needed for Colour

Sense.

Memorizing the colours

If the performer simply retrieved the

shuffled deck, looked at the cards and

later named the colours, the result

would hardly be deceptive. This is

where the concept of “Performing,

Mode” comes in. | will try to describe

Colour Sense exactly as | perform it

at the moment. The situation is seated

ata table together with the spectators.

When the spectator has finished shuf-

fling, retrieve the deck and hold the

cards face-up in left-hand dealing posi-

tion. Instead of directing attention to

the deck, look around the table and

say “Ok, let’s see, we need some space

here...” As you say that and gesture

with your right hand, your left thumb

pushes over the top two cards, allowing

you to see and remember the first

triplet. Spectators usually start moving

a few glasses, napkins or the card case

out of the way. Apparently you are set:

ting the stage for the demonstration.

Say something along the lines of: “Hm,

well...[ don’t know...how shall we do

it...” apparently thinking about exactly

how to continue. During this, absent:

mindedly spread the deck face-up

between your hands and look at the

cards without really paying attention

to them. You know the feeling: You do

not really look at the cards, but almost.

through them. Your gaze simply hap

pens to fall onto your hands and the

deck as you are momentarily Jost in

thought.

In fact, of course, you look at the cards

in triplets and form and remember the

short code-word as described above.

Finally, remember the next (thirteenth)

card — suit and value.

Four packets

As soon as you know all you need, sud:

denly square the deck, taking a break

under the thirteenth card from the face,

sit up, look directly at the spectators

and say “Ah, I know!”, as if something

had suddenly occurred to you. Immedia-

tely take the memorized packet above

the break and place it onto the table

face-down. Follow by placing another

quarter of the deck face-down to the left

of the first and then two more packets,

one to the right and one to the left of

the first two. You have made four piles

with the memorized packet second from

the right. Done a bit sloppy, this division

into packets appears arbitrary.

A Force

With your left hand resting behind

the second packet from the left, ask

the spectator to your right to “take

one packet and hold it under the table”

(Photo 2). If you give this direction no

importance whatsoever you will find

that he will almost always take the

second packet from your right. (You

will find a few words on this age-old

psychological force and a very simple

Out in case the spectator takes any

other pile in the comments.) As soon

as he takes the cards under the table,

push the other packets out of the way

to the side. This sequence should give

the impression that you spontaneously

came up with a handling for having the

spectator take only about a quarter of

the deck under the table in order to

speed up the demonstration.

Now switch back to Performing Mode

by officially recapping what happened

and getting ready for work: “Ok, you

shuffled the deck and took some cards

under the table. Very good.” Announce

that you will try to feel the colours of

the cards.

Feeling colours ...and more

Place your right hand onto the table,

directly above the spectator’s packet,

With your palm touching the table

top, slowly move your hand around

faith-healer-style, supposedly starting

to feel through the table (Photo 3,

which shows a moment in the middle

of the routine with some correctly

felt cards already on the table). Look

at your hand intently. After a little

while, the “connection” is there, and

you stop short: “Oh,” you say to your

spectator, “can you turn the packet

face-up, please!?” Apart from bringing

a smile, playful little interludes like

this help letting some time pass

before the beginning of the actual

demonstration, further separating the

method from the effect.

The spectator turns over the packet.

Gaze at the table, feel some more,

and finally say: “Ah, yes! Very good!

The first card is red!” Have him reach

under the table with his other hand

and remove the top card of the packet

to place it onto the table. It is indeed

a red card. Look around expectantly.

As the chance of success was fifty/fifty,

there will be no big reaction except

maybe for some mock applause. “Shall I

try one more?” you offer and repeat fee-

ling the table-surface above the packet.

Name the colour of the next card and

have the spectator place it onto the

table as well. Now, you really get going:

Naming the colour of card after card,

have him place the cards onto the table

face-up. You will find that the procedure

holds interest for quite a while: For

the first few cards people are not sure

what to think - after all you might just

be lucky. The more cards you identify

correctly, however, the spookier your

demonstration gets. Some spectators

might desperately wait for a first mistake.

To keep things even more interesting try

to vary the rhythm, maybe having some

difficulty with one card or naming the

next one immediately as the spectator

places the last one onto the table, etc.

‘Another idea that creates a very memor-

able moment during this naming of the

colours is described in the comments.

When you have named the colours of

the first nine cards (as you remembered

the colours in triplets you will not have

to count to know when that point is

reached) you know that the spectator

has exactly four cards left, At that point

I try to induce a challenge by conti-

dently stating: “I can see everything!

All the cards under the table. Very easy!

Do you still have some!? Yes? How

many?” I am not sure whether this

works on paper, but the combination

of claiming to “see everything” imme-

diately followed by asking whether

the spectator still has some cards and

how many, more often than not causes

somebody half-jokingly to challenge the

performer to feel for himself. If your

little gamble does not work, nothing is

lost; simply get the idea yourself before

the spectator has a chance to answer

and feel for the number of cards. If it

works, however, it gives you an oppor-

tunity to milk the situation, creating a

very strong moment by accepting the

challenge (see Inducing Challenges

page 60.) Have the spectator carefully

spread the cards into a little fan and

pretend to count the cards through

the table “Ah yes, that’s one, two,

three...four...four more cards! Very

good.” Continue naming the colour

of the next three cards, having the

spectator place them onto the table

as before. For the last card, you get the

idea to try and go “all the way”: Have

the spectator press the card against the

table from below. Feel through the table

and name first the colour and then

hesitantly also its suit and value. The

spectator brings up the card and shows

your sensation was accurate, bringing

this unusual demonstration to a nicely

pointed finish.

Credits and Comments

I want to thank Michael Weber for let

ting me describe Colour Sense in this

booklet. Among other wonderful things

he showed me a similar routine during

a late-night session at a convention in

Japan a few years ago. The changes I

made are the exact handling of memori-

zing the cards (using the “Performing

Mode”-concept as main cover), the

induced challenge near the end, the

additional detail described below and

the notion of feeling the cards through

a table. This last point directs the spec-

tators’ attention towards sight or maybe

even touch, effectively dissociating

it from the actual method (memory).

‘Many thanks go to Lewis Jones from

London who generously agreed to let

me include his clever and very useful

“Pattern Principle”.

On Forcing

When forcing one of four identical

objects as described, placing the left

hand behind the second packet from

the left seems to increase the chance of

success: The left hand effectively blocks

the packet at the far left, all but elimina-

40

ting it from being chosen, and visually

emphasizes the force-packet as the

centre packet of the first three (Photo 1

again). This detail was first pointed out

to me by Helge Thun. Hossa!

Also note that you do not say “choose

any packet...” but “take one packet...”,

this phrase being less likely to make the

spectator think too much about his

“choice”. Finally, the instructions are

immediately continued (“...and hold it

under the table”) letting the spectator

little time to make a conscious decision.

More on this and other linguistic

strategies can be found (among others}

in Kenton Knepper’s “Wonder Words”

audio-tapes and just about everywhere

in the work of Juan Tamariz.

The Out

What happens, if the spectator takes any

other packet under the table? After all,

you have no idea about the colour of any

of his cards. Easy: Just ask a second spec-

tator also to take a packet. If he doesn’t

take the memorized packet either, conti-

nue with a third spectator. If the force-

packet is left on the table — perfect: Say

“Ok, and I need one of you to help me

for this...” Having established one spec-

tator who does not yet have a packet as

your helper hand him the remaining

pile. Let each of the three other specta-

tors guess the colour of the top card of

their packets. Have them check and com-

ment on their success or failure. Then

collect their cards and place them aside.

Do the routine with your “helper” as de-

scribed. Exactly the same happens in any

of the other cases: The non-memorized

packets are simply used as demo-piles.

Implications

Here is one additional touch that can

greatly contribute to the fiction of

“feeling colours through a table”:

When retrieving the shuffled deck,

cut the cards so that the sixth card

from the face is the first picture card.

Then remember the colours as described.

During performance, you name the

colour of the first card: It is correct.

Second card: Correct. Continue like

this until you come to the sixth card.

Here, name the wrong colour and im:

mediately correct yourself: “The next

one is...black, ah no, red!” A second

before the spectator brings the card up,

turn to the spectators towards your left

and apologize: “I still have trouble with

those picture cards.” Everybody will

see that the card is indeed the first

picture card, making this underplayed

moment a very strong one.

High Noon

Effect

Ina dramatic duel, the performer ma-

nages to snatch a selected card from

an assistant's hand. Not only does the

performer achieve this in lightning

speed, he also finds time to fold the

card neatly in quarters and sneak it

under the spectator's watch.

Method Overview

A duplicate card is loaded under the

spectator’s watch before the “duel”

begins.

Preparation

Neatly fold one duplicate card in quar:

ters face outwards (Photo 1). Keep the

folded duplicate in a pocket and cut

the corresponding card to the top of

the deck.

Performance

Secretly obtain the folded duplicate in

your right hand and clip it between your

first and second fingers (Photo 2). Ann-

ounce that you will stage a “duel” with

one of the spectators. Ask one spectator

to hold out his hand and all the other

spectators to stand in a circle around

the two of you, forming kind of an

impromptu arena. As you pull your op:

ponent a bit closer towards yourself

secretly load the card under his watch.

To do that, simply slide the clipped card

under the watch as you pull the specta-

tor towards you (Photo 3). The load

itself is not overly difficult, the main

cover being that you have not yet swit:

ched to Performing Mode. You are just

organizing the contest, arranging the

spectators in a circle, asking one of

them to hold out his hand, etc. The

actual duel has not yet started. Try

to create an atmosphere of expectation,

}

|

at the same time implying, that for now,

you are simply setting the stage.

With the audience more or less surroun-

ding you, the folded duplicate safely loa-

ded and your assisting spectator holding

out his hand, cut the deck and establish

an angle jog (or simply a break} above

the former top card in preparation for a

dribble force. Execute this force, dribb

ling the cards onto the spectator's hand,

45,

asking him to stop you whenever he

likes. To make sure the cards do not

spill all across his hand and to the floor,

you can use your left hand to support

and steady his (Photo 4). At the moment

he stops you, let all the cards below the

jog (or break) drop onto his hand. Hand

the rest of the cards to another specta~

tor. Show the top card of your assistant’s

pile around, emphasizing that you will

not peek at the card, then put it back

on top of the pile and briefly pick up

all the cards from his hand. Ask him

to keep his hand there as a table for a

second. This prevents him from drop:

ping his hand to the side, prematurely

revealing the folded c

who might happen to look there.

You will apparently lose the selection

anywhere in the packet, actually just

adding five cards on top of it using a

jog shuffle as follows: Undercut half

the packet, run five cards on top of the

selection, injog the next card and shuf-

fle off. Establish a break under the Injog,

shuffle off to this break and throw the

rest on top. The selection ends up sixth

from the top.

Briefly and clearly explain the “duel”:

You are going to show your spectator

one card after the other and place them

onto his hand. As soon as his selection

is on his hand, he is to slap his other

hand on top of it as quickly as he can.

You try to sneak the card away before

he can get it. He has the advantage of

knowing the card while you have to

watch him closely in order to know

when to strike, But of course, you

have years of training.

Asa trial-run, place the first card onto

the spectator’s hand very delicately and

ask him to quickly slam his other hand

on top. This rehearsal serves a triple

purpose: First and most importantly, the

spectator overcomes any possible inhibi

tions he might have really to hit his

hand and the card very quickly. If he

is overly hesitant, do it again, coaching

him to really go for it! Secondly, the

other spectators can easily see what this

is all about, And finally, you can make

some amusing comments along the lines

of: “Oh, you're fast! Let me try this with

someone else!” further building the

conflict. Also, tell him to keep the card

covered with his hand in case he gets it.

Otherwise, you explain, you could wait

until he let’s go of his card and quickly

sneak it away afterwards. In fact, this is

to ensure he doesn’t look at the card too

early. As long as he holds his supposed

selection between his hands, it will be

you who controls the timing.

Then the game starts for real. You give

the signal and start to clearly show card

after card and place them onto his hand.

For the fourth card do a double turn-

over. Make sure to mention the name

of this card: "The Two of Diamonds,

maybe?” Turn the double card face-

down again and place the top card onto

his hand. The next card is a double

again and the selection will show. Place

the top card onto his hand and -WHAM!

his hand crashes down on top of it.

After a short pause, say: "Ah, that was

close... am glad I got it at all!”

To your spectators, the first part of this

sounds like a weak excuse. The second

sentence should cause some irritation.

Pause meaningfully to give your specta-

tors time to suspect the unbelievable.

Point to his hands and say: “Ten of Spa

des, right?” '. “Take a look.” He will

look at the top card in his hand, fully

expecting his Ten of Spades. Instead,

he will find the card that has been put

there before — the Two of Diamonds.

' Pointing to his hands as you name the card is purposely ambiguous. The sentence and the gesture in effect say two

different things: “Your card was the Ten of Spades” and "The Ten of Spades is between your hands”, By confirming,

that his card was indeed the Ten, he cannot help aso confirming that the card is stil between his hands. This

effectively dramatizes the moment he discovers his card missing: after all it was stil there a moment ago — hasn’t

he said so himset!?

‘As you named this card earlier most

spectators will realize this actually is the

card that came before the Ten of Spades.

Most of the time, the spectator checks

all the cards in his hands. As he holds

only five cards, pacing remains mostly

under your control.

This, of course, is the first climax,

‘As those of you who regularly perform

“Reflex” know, the reaction at that

point can be quite strong and last a

while. I think it is important to let the

spectators fully appreciate this moment

before revealing the second climax.

Given enough time, some spectators

might even inquire about the selected

card themselves. Only when you have

all their attention again, explain: “1

| sneaked your card out there just before

you could get it, and then I folded it

| exactly in half. Then, I folded it in half

again. It took me about twenty milli-

seconds. Did you look at your watch?"

Usually, you will get some irritated

laughs, as some of your spectators might

not be sure what to believe anymore.

After a final pause simply say: “Look at

your watch.” (Photo 5).

Credits and Comments

Credit obviously goes to Paul Harris,

whose modern classic “Reflex” was first

described by Michael Ammar for the

‘Magical Arts Journal. A very complete

description can be found in Paul Harris’,

The Art of Astonishment Vol.3, “Whack

Your Pack” pp.207, USA 1996.

A big Thank-You goes to Andreas Buchty

from Freiburg, together with whom the

idea of combining “The Card Under the

Spectator's Watch” with Paul Harris’

“Reflex” was developed. Mare Kanert

from Frankfurt also experimented along

the same lines.

As this ending uses a duplicate card, the

selection cannot be freely thought-of as

in the original handling, On the other

hand, this allows you to control the

exact moment the selection appears. For

me, the timing works best with the card

being the fifth one shown as described.

Furthermore, the fact that the selection

is controlled to a known position allows

you to take single cards very clearly

before doing the two double turnovers.

This of course helps to cancel the idea

of a switch. A similar handling is also

used by Christian Scherer from Switzer-

land who published his version of

“Reflex” in Scherer, Christian, Karten

ala carte, ,Reflexartig“, pp. 172,

Thun, 1997,

The effect of a folded card appearing

under a spectator’s wristwatch has seen

print before in an effect by Norman

Beck, which can be found in Genii

Magazine, vol. 58 No 7, p. 513,

May 1995.

This routine is all about conflict (and

you may want to have a very tall or

strong spectator assist you for this effect,

silently emphasizing this aspect.) How-

ever, this conflict is about the situation,

not about the spectator. Dramatize the

“duel” as much as you can but at the

same time make it very clear, that it has

nothing to do with your helper as a per-

son. You may talk about your “years of

practise” and that nobody has ever bea-

ten you, etc. This way, without losing

the necessary tension, you take the sting

out of the personal aspect, and your as-

sistant will be happy having played with

a professional, instead of feeling foolish

because he “lost”.

For me, the most difficult aspect of

“Reflex” always was the reproduction

of the missing card. The spectator’s

reaction to finding the selection missing

from his hands often creates a huge

off-beat. If this relaxation lasts a while,

pulling the card out of the pocket or

even the wallet afterwards is hardly

surprising anymore; after all you could

have placed the card anywhere while

everybody was distracted. Having the

card appear under the spectator’s watch,

however, does not suffer from that pro-

blem. The reaction from the “vanish” of

the card, as strong and lasting as it may

be does not weaken the final revelation

of the card.

The other small contributions High

Noon may have to offer are placing the

cards onto the spectator’s hand instead

of onto the table and the brief rehearsal

with the spectator before starting the

actual contest. Apart from making it

possible to perform the routine without

a table, which in turn allows for a group

to gather around, giving the conflict

kind of an “arena” or “street-fight”-feel,

placing the cards onto the spectator’s

hand usually makes for a better WHACK!

Whereas most spectators hesitate to slap

a table set with full wine-glasses and

silverware, few have any trouble hitting

cards on their hand. The rehearsal with

the spectator makes sure you really get

a strong, dramatic moment.

You might also like

- ALL HOOVER VACUUMS 25% OFFDocument1 pageALL HOOVER VACUUMS 25% OFFwax00rNo ratings yet

- Atlas CopcoDocument1 pageAtlas Copcowax00rNo ratings yet

- Atlas CopcoDocument1 pageAtlas Copcowax00rNo ratings yet

- Euro-Asia Builders Center: Greenfield Hand Tools AUGUST 01,2011Document3 pagesEuro-Asia Builders Center: Greenfield Hand Tools AUGUST 01,2011wax00rNo ratings yet

- Euro-Asia Builders Center: Greenfield Hand Tools AUGUST 01,2011Document3 pagesEuro-Asia Builders Center: Greenfield Hand Tools AUGUST 01,2011wax00rNo ratings yet

- GF MeasuringDocument2 pagesGF Measuringwax00rNo ratings yet

- Greenfield Hand Tools Catalog with PricesDocument5 pagesGreenfield Hand Tools Catalog with Priceswax00rNo ratings yet

- Greenfield Hand Tools Catalog with PricesDocument5 pagesGreenfield Hand Tools Catalog with Priceswax00rNo ratings yet

- Euro-Asia Builders Center: Cat. NosDocument6 pagesEuro-Asia Builders Center: Cat. Noswax00rNo ratings yet

- Euro-Asia Builders Center: Locksets & DeadboltsDocument1 pageEuro-Asia Builders Center: Locksets & Deadboltswax00rNo ratings yet

- Adjustable Wrench and Pliers Price List February 2007Document1 pageAdjustable Wrench and Pliers Price List February 2007wax00rNo ratings yet

- Foam Insulation Sheet Sizes and PricesDocument1 pageFoam Insulation Sheet Sizes and Priceswax00rNo ratings yet

- Euro-Asia Builders Center: Effective May 15, 2011Document5 pagesEuro-Asia Builders Center: Effective May 15, 2011wax00rNo ratings yet

- Euro-Asia Builders Center: True TemperDocument2 pagesEuro-Asia Builders Center: True Temperwax00rNo ratings yet

- Clarifying Official Receipt Requirements for BusinessesDocument2 pagesClarifying Official Receipt Requirements for BusinessesDante Bauson JulianNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)