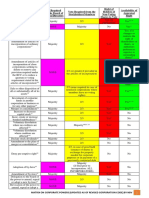

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Foreign Corporations

Uploaded by

Rache GutierrezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Foreign Corporations

Uploaded by

Rache GutierrezCopyright:

Available Formats

CORPORATION

LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

FOREIGN CORPORATIONS

branch with regard to external matters, but the

governing law for internal matters would be the law of

their home country (e.g. where foreign company

decides to sell all its Philippine assets, such cannot be

questioned because it is an internal matter that is

governed by the laws of the home country of the

I.

Definition;

Nature

of

a

Foreign

Corporation

A.

Definition

(Section

123)

Section

123.

Definition

and

rights

of

foreign

corporations.

For

the

purposes

of

this

Code,

a

foreign

corporation

is

one

formed,

organized

or

existing

under

any

laws

other

than

those

of

the

Philippines

and

whose

laws

allow

Filipino

citizens

and

corporations

to

do

business

in

its

own

country

or

state.

It

shall

have

the

right

to

transact

business

in

the

Philippines

after

it

shall

have

obtained

a

license

to

transact

business

in

this

country

in

accordance

with

this

Code

and

a

certificate

of

authority

from

the

appropriate

government

agency.

(n)

foreign

corporation.)

B.

Two

requirements

to

be

considered

a

foreign

corporation:

1. Organized

in

another

country.

o Regardless

of

the

ownership

(e.g.

a

corporation

organized

under

foreign

laws

even

if

wholly

owned

by

Filipinos)

2. The

laws

of

the

corporations

home

state

allows

for

Filipino

citizens

and

corporations

to

do

business

thereat

(policy

of

reciprocity).

o The

presence

of

absence

of

reciprocity

affects

its

capacity

to

do

business

in

the

Philippines.

A foreign corporation is one which owes its existence to the

laws of another state, and generally, has no legal existence

within the State in which it is foreign. Avon Insurance PLC v.

Court of Appeals, 278 SCRA 312 (1997)

C.

Nature

of

the

Corporate

Creature

Atty. Hofilea this part of the Corporation Code deals with

foreign corporations who establish a presence here on their

own as such (i.e. branch), thereby, there is only one juridical

entity. This does not contemplate situations wherein the foreign

corporation establishes a domestic corporation as its subsidiary,

thereby, there are two juridical entities.

o Foreign Corporations who apply for a license would

thereby establish a branch. It does not acquire a new

personality. The Corporation Code will apply on the

A corporation is essentially a creature of the state under the

laws of which it has been granted its juridical personality; and

strictly speaking, beyond the territories of such creating state, a

corporation has no legal existence, since the powers of the

creating laws do not extend beyond the territorial jurisdiction of

the state under which it is created.1

Marshall-Wells Co. v. Henry W. Elser & Co., 46 Phil. 70, at p. 74 (1924).

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

A foreign corporation is one which owes its existence to the

laws of another state, and generally, has no legal existence

within the state in which it is foreign.1

It is a fundamental rule of international jurisdiction that no state

can by its laws, and no court (which is only a creature of the

state) can by its judgments or decrees, directly bind or affect

effect within the state.7 For example, the filing of an

action by a foreign corporation before Philippine courts

would mean that by voluntary appearance, the local

courts have actually obtained jurisdiction over the

"person" of the foreign corporation.8

2. Doctrine of "doing business" within the territorial jurisdiction

of the host state. It is an established doctrine that when a

property or persons beyond the limits of that state.2 However,

under the doctrine of comity in international laws, "a

corporation created by the laws of one state is usually allowed

to transact business in other states and to sue in the courts of

the forum."3

1. Consent. The legal standing of foreign corporations in the host

state therefore is founded on international law on the basis of

consent,4 and the extent by which a hosting state can enforce its

foreign corporation undertakes business activities within the

territorial jurisdiction of a host state, then it ascribes to the host

states laws, rules and regulations. In the same manner, in order

to regulate the basis by which a foreign corporation seeks to do

business and the manner by which it would seek redress within

the judicial and administrative authorities within the host state,

have given rise to the requirement that a license be obtained

laws and jurisdiction over corporations created by other states

has been the subject of jurisprudential rules and municipal

legislations, especially in the fields of taxation, 5 foreign

investments, and capacity to obtain reliefs in local courts and

administrative bodies.6

under the penalty that failure to do so would not give it legal

standing to sue in local courts and administrative bodies

exercising quasi-judicial powers.9

Avon

Insurance

PLC

v.

Court

of

Appeals,

278

SCRA

312,

86

SCAD

401

(1997).

Times,

Inc.

v.

Reyes,

39

SCRA

303

(1971),

citing

Perkins

v.

Dizon,

69

Phil.

186

(1939).

3

Times,

Inc.

v.

Reyes,

39

SCRA

303

(1971),

citing

Paul

v.

Virginia,

8

Wall.

168

(1869);

Sioux

Remedy

Co.

v.

Cape

and

Cope,

235

U.S.

197

(1914);

Cyclone

Mining

Co.

v.

Baker

Light

&

Power

Co.,

165

Fed.

996

(1908).

4

SALONGA,

PRIVATE

INTERNATIONAL

LAW,

1979

ed.,

p.

344.

5

The

chapter

does

not

cover

nor

discuss

the

concept

of

"doing

business"

in

the

field

of

taxation,

as

the

subject

is

itself

a

technical

matter

that

deserves

a

separate

discussion.

6

Villanueva,

C.

L.,

&

Villanueva-Tiansay,

T.

S.

(2013).

Philippine

Corporate

Law.

(2013

ed.).

Manila,

Philippines:

Rex

Book

Store.

Consent, as a requisite for jurisdiction over foreign

corporations, is founded on considerations of due

process and fair play.

A foreign corporation may be subjected to jurisdiction

by reason of consent, ownership of property within the

State, or by reason of activities within or having an

SALONGA, supra, citing Goodrich (Scoles), 136.

Communication Materials and Design, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, 260 SCRA 673,

73 SCAD 374 (1996).

9

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

8

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

On the other hand, when a foreign corporation's

activities within the host state do not fall within the

concept of "doing business," the requirements of

obtaining a license to engage in business are generally

not applicable to it, and it would still have legal standing

to sue in local courts and administrative agencies to

obtain relief. In such an instance, the jurisdiction by

local courts and administrative bodies over a foreign

corporation seeking relief would be the clear consent

manifested by the filing of the suit.1

II.

License

to

Do

Business

in

the

Philippines

A.

Application

for

License

(Sections

124

and

125;

Art.

48,

Omnibus

Investment

Code)

Section

124.

Application

to

existing

foreign

corporations.

Every

foreign

corporation

which

on

the

date

of

the

effectivity

of

this

Code

is

authorized

to

do

business

in

the

Philippines

under

a

license

copy of its articles of incorporation and by-laws, certified in

accordance with law, and their translation to an official language of

the Philippines, if necessary. The application shall be under oath and,

unless already stated in its articles of incorporation, shall specifically

set forth the following:

1. The date and term of incorporation;

2. The address, including the street number, of the principal office of

the corporation in the country or state of incorporation;

3. The name and address of its resident agent authorized to accept

summons and process in all legal proceedings and, pending the

establishment of a local office, all notices affecting the corporation;

4. The place in the Philippines where the corporation intends to

operate;

5. The specific purpose or purposes which the corporation intends to

therefore

issued

to

it,

shall

continue

to

have

such

authority

under

the

terms

and

condition

of

its

license,

subject

to

the

provisions

of

this

Code

and

other

special

laws.

(n)

Section

125.

Application

for

a

license.

A

foreign

corporation

applying

for

a

license

to

transact

business

in

the

Philippines

shall

submit

to

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

a

pursue in the transaction of its business in the Philippines: Provided,

That said purpose or purposes are those specifically stated in the

certificate of authority issued by the appropriate government agency;

6. The names and addresses of the present directors and officers of the

corporation;

7. A statement of its authorized capital stock and the aggregate

number of shares which the corporation has authority to issue,

itemized by classes, par value of shares, shares without par value, and

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

series,

if

any;

8.

A

statement

of

its

outstanding

capital

stock

and

the

aggregate

number

of

shares

which

the

corporation

has

issued,

itemized

by

classes,

par

value

of

shares,

shares

without

par

value,

and

series,

if

and

liabilities

of

the

corporation

as

of

the

date

not

exceeding

one

(1)

year

immediately

prior

to

the

filing

of

the

application.

Foreign

banking,

financial

and

insurance

corporations

shall,

in

addition

to

the

above

requirements,

comply

with

the

provisions

of

existing

laws

any;

9.

A

statement

of

the

amount

actually

paid

in;

and

10.

Such

additional

information

as

may

be

necessary

or

appropriate

in

order

to

enable

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

to

determine

whether

such

corporation

is

entitled

to

a

license

to

transact

business

applicable to them. In the case of all other foreign corporations, no

application for license to transact business in the Philippines shall be

accepted by the Securities and Exchange Commission without previous

authority from the appropriate government agency, whenever

required by law. (68a)

in the Philippines, and to determine and assess the fees payable.

Attached to the application for license shall be a duly executed

certificate under oath by the authorized official or officials of the

jurisdiction of its incorporation, attesting to the fact that the laws of

the country or state of the applicant allow Filipino citizens and

corporations to do business therein, and that the applicant is an

B. Rationale for Requiring License:

existing corporation in good standing. If such certificate is in a foreign

language, a translation thereof in English under oath of the translator

shall be attached thereto.

The application for a license to transact business in the Philippines

shall likewise be accompanied by a statement under oath of the

president or any other person authorized by the corporation, showing

to the satisfaction of the Securities and Exchange Commission and

other governmental agency in the proper cases that the applicant is

solvent and in sound financial condition, and setting forth the assets

Section 69 of old Corporation Law was intended to subject the

foreign corporation doing business in the Philippines to the

jurisdiction of our courts and not to prevent the foreign

corporation from performing single acts, but to prevent it from

acquiring domicile for the purpose of business without taking

the necessary steps to render it amenable to suit in the local

courts. Marshall-Wells v. Elser, 46 Phil. 71 (1924).

Marshall-Wells v. Elser

Facts:

Marshall-Wells

Company

(an

Oregon,

U.S.

corporation)

sued

Henry

W.

Elser

&

Co.,

Inc.

(a

domestic

corporation)

in

CFI

Manila

for

the

unpaid

balance

on

goods

it

sold

to

the

latter.

Henry

W.

Elser

&

Co.,

Inc.

averred

that

Marshall-Wells

Company

has

no

legal

capacity

to

sue

since

there

is

no

showing

that

it

has

complied

with

the

laws

of

Philippines,

particularly

Section

69

of

the

Corporation

Law

where

it

states:

No

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

foreign

corporation

shall

be

permitted

to

maintain

by

itself

or

assignee

any

suit

for

the

recovery

of

any

debt,

claim,

or

demand

whatever,

unless

it

shall

have

the

license

prescribed

in

section

68

of

the

law.

Issue:

Whether

or

not

the

obtaining

of

the

license

prescribed

in

section

68,

as

amended,

of

the

Corporation

Law

is

a

condition

precedent

to

the

maintaining

of

any

kind

of

action

in

the

courts

of

the

Philippine

Islands

by

a

foreign

corporation.

Held:

NO.

The

SC

decided

in

favor

of

Marshall

Wells

Co.

The

implication

of

the

law

is

that

it

was

never

the

purpose

of

the

Legislature

to

exclude

a

foreign

corporation

which

happens

to

obtain

an

isolated

order

for

business

from

the

Philippines,

from

securing

redress

in

the

Philippine

courts,

and

thus,

in

effect,

to

permit

persons

to

avoid

their

contracts

made

with

such

foreign

corporations.

Doctrine:

The

effect

of

the

statute

preventing

foreign

corporations

from

doing

business

and

from

bringing

actions

in

the

local

courts,

except

on

compliance

with

elaborate

requirements,

must

not

be

unduly

extended

or

improperly

applied.

It

should

not

be

construed

to

extend

beyond

the

plain

meaning

of

its

terms,

considered

in

connection

with

its

object,

and

in

connection

with

the

spirit

of

the

entire

law.

Otherwise, a foreign corporation illegally doing business here

because of its refusal or neglect to obtain the required license

to do business may successfully though unfairly plead such

neglect or illegal act so as to avoid service and thereby impugn

the jurisdiction of the local courts. Avon Insurance PLC v. Court

of Appeals, 278 SCRA 312 (1997).

The same danger does not exist among foreign corporations

that are indubitably not doing business in the Philippines: there

would be no reason for it to be subject to the States regulation;

for in so far as the State is concerned, such foreign corporation

has no legal existence. Therefore, to subject such foreign

corporation to the local courts jurisdiction would violate the

essence of sovereignty of the creating state. Avon Insurance

PLC v. Court of Appeals, 278 SCRA 312 (1997).

C.

Appointment

of

a

Resident

Agent

(Section

127

and

128)

Section

127.

Who

may

be

a

resident

agent.

A

resident

agent

may

be

either

an

individual

residing

in

the

Philippines

or

a

domestic

corporation

lawfully

transacting

business

in

the

Philippines:

Provided,

That

in

the

case

of

an

individual,

he

must

be

of

good

moral

character

and

of

sound

financial

standing.

(n)

Section

128.

Resident

agent;

service

of

process.

The

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

shall

require

as

a

condition

precedent

to

the

issuance

of

the

license

to

transact

business

in

the

Philippines

by

any

foreign

corporation

that

such

corporation

file

with

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

a

written

power

of

attorney

designating

some

person

who

must

be

a

resident

of

the

Philippines,

on

whom

any

summons

and

other

legal

processes

may

be

served

in

all

actions

or

other

legal

proceedings

against

such

corporation,

and

consenting

that

service

upon

such

resident

agent

shall

be

admitted

and

held

as

valid

as

if

served

upon

the

duly

authorized

officers

of

the

foreign

corporation

at

its

home

office.

Any

such

foreign

corporation

shall

likewise

execute

and

file

with

the

Securities

and

Exchange

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

Commission

an

agreement

or

stipulation,

executed

by

the

proper

authorities

of

said

corporation,

in

form

and

substance

as

follows:

"The

(name

of

foreign

corporation)

does

hereby

stipulate

and

agree,

in

consideration

of

its

being

granted

by

the

Securities

and

Exchange

against forum shoppingwhile a resident agent may be aware

of actions filed against his principal (a foreign corporation doing

business in the Philippines), he may not be aware of actions

initiated by its principal, whether in the Philippines or abroad.

Expertravel & Tours, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, 459 SCRA 147

(2005).

Commission a license to transact business in the Philippines, that if at

any time said corporation shall cease to transact business in the

Philippines, or shall be without any resident agent in the Philippines

on whom any summons or other legal processes may be served, then

in any action or proceeding arising out of any business or transaction

which occurred in the Philippines, service of any summons or other

legal process may be made upon the Securities and Exchange

Commission and that such service shall have the same force and effect

as if made upon the duly-authorized officers of the corporation at its

home office."

Whenever such service of summons or other process shall be made

upon the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commission shall,

within ten (10) days thereafter, transmit by mail a copy of such

summons or other legal process to the corporation at its home or

principal office. The sending of such copy by the Commission shall be

necessary part of and shall complete such service. All expenses

incurred by the Commission for such service shall be paid in advance

by the party at whose instance the service is made.

In case of a change of address of the resident agent, it shall be his or

its duty to immediately notify in writing the Securities and Exchange

Commission of the new address. (72a; and n)

Being a resident agent of a foreign corporation does not mean

that he is authorized to execute the requisite certification

A complaint filed by a foreign corporation is fatally defective for

failing to allege its duly authorized representative or resident

agent in Philippine jurisdiction. New York Marine Managers,

Inv. c. Court of Appeals, 249 SCRA 416 (1995).

When a corporation has designated a person to receive service

of summon pursuant to the Corporation Code, the designation

is exclusive and service of summons on any other person is

inefficacious. H.B. Zachry Company Intl v. Court of Appeals,

232 SCRA 329 (1994)

D.

Issuance

of

License

(Section

126;

Art.

49,

Omnibus

Investment

Code)

Section

126.

Issuance

of

a

license.

If

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

is

satisfied

that

the

applicant

has

complied

with

all

the

requirements

of

this

Code

and

other

special

laws,

rules

and

regulations,

the

Commission

shall

issue

a

license

to

the

applicant

to

transact

business

in

the

Philippines

for

the

purpose

or

purposes

specified

in

such

license.

Upon

issuance

of

the

license,

such

foreign

corporation

may

commence

to

transact

business

in

the

Philippines

and

continue

to

do

so

for

as

long

as

it

retains

its

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

authority

to

act

as

a

corporation

under

the

laws

of

the

country

or

state

of

its

incorporation,

unless

such

license

is

sooner

surrendered,

revoked,

suspended

or

annulled

in

accordance

with

this

Code

or

other

special

laws.

additional securities deposited with it if the gross income of the

licensee has decreased, or if the actual market value of the total

securities on deposit has increased, by more than ten (10%) percent of

the actual market value of the securities at the time they were

deposited. The Securities and Exchange Commission may, from time to

Within

sixty

(60)

days

after

the

issuance

of

the

license

to

transact

business

in

the

Philippines,

the

license,

except

foreign

banking

or

insurance

corporation,

shall

deposit

with

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

for

the

benefit

of

present

and

future

creditors

of

the

licensee

in

the

Philippines,

securities

satisfactory

to

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission,

consisting

of

bonds

or

other

evidence

of

indebtedness

of

the

Government

of

the

Philippines,

its

political

time,

allow

the

licensee

to

substitute

other

securities

for

those

already

on

deposit

as

long

as

the

licensee

is

solvent.

Such

licensee

shall

be

entitled

to

collect

the

interest

or

dividends

on

the

securities

deposited.

In

the

event

the

licensee

ceases

to

do

business

in

the

Philippines,

the

securities

deposited

as

aforesaid

shall

be

returned,

upon

the

licensee's

application

therefor

and

upon

proof

to

the

satisfaction

of

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

that

the

licensee

has

no

liability

subdivisions and instrumentalities, or of government-owned or

controlled corporations and entities, shares of stock in "registered

enterprises" as this term is defined in Republic Act No. 5186, shares of

stock in domestic corporations registered in the stock exchange, or

shares of stock in domestic insurance companies and banks, or any

combination of these kinds of securities, with an actual market value

of at least one hundred thousand (P100,000.) pesos; Provided,

to Philippine residents, including the Government of the Republic of

the Philippines. (n)

however,

That

within

six

(6)

months

after

each

fiscal

year

of

the

licensee,

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

shall

require

the

licensee

to

deposit

additional

securities

equivalent

in

actual

market

value

to

two

(2%)

percent

of

the

amount

by

which

the

licensee's

gross

income

for

that

fiscal

year

exceeds

five

million

(P5,000,000.00)

pesos.

The

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

shall

also

require

deposit

of

additional

securities

if

the

actual

market

value

of

the

securities

on

deposit

has

decreased

by

at

least

ten

(10%)

percent

of

their

actual

A foreign corporation licensed to do business should be

subjected to no harsher rules that is required of domestic

corporation and should not generally be subject to attachment

on the pretense that such foreign corporation is not residing in

the Philippines. Claude Neon Lights v. Phil. Advertising Corp.,

57 Phil. 607 (1932).

E.

Effects

of

Being

Issued

License

market

value

at

the

time

they

were

deposited.

The

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission

may

at

its

discretion

release

part

of

the

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

The Corporation Code therefore takes pain to ensure that in

allowing a foreign corporation to engage in business activities in

the Philippines, proper safeguards are taken to allow obtaining

jurisdiction over such foreign corporation in case of suit and

that proper securities are present within Philippine jurisdiction

to answer for a foreign corporation's obligations to locals. The

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

Supreme

Court

has

held:

"The

purpose

of

the

law

is

to

subject

the

foreign

corporation

doing

business

in

the

Philippines

to

the

jurisdiction

of

our

courts.

It

is

not

to

prevent

the

foreign

corporation

from

performing

single

or

isolated

acts,

but

to

bar

it

from

acquiring

a

domicile

for

the

purpose

of

business

without

first

taking

steps

necessary

to

render

it

amenable

to

suits

in

the

1

local

courts."

1. Licensed

Foreign

Corporation

Deemed

Domesticated

The harmony and balance sought to be achieved by our "doing

business" requirements for obtaining license are best

exemplified by the fact that once a foreign corporation has

obtained a license to do business, then it is deemed

domesticated, and should be subject to no harsher rules that is

required of domestic corporations.2

F.

Amendment

of

License

(Section

131)

Section

131.

Amended

license.

A

foreign

corporation

authorized

to

transact

business

in

the

Eriks

Pte.

Ltd.

v.

Court

of

Appeals,

267

SCRA

567,

76

SCAD

70

(1997).

The

Court

also

held

in

that

case:

"It

was

never

the

intent

of

the

legislature

to

bar

court

access

to

a

foreign

corporation

or

entity

which

happens

to

obtain

an

isolated

order

for

business

in

the

Philippines.

Neither,

did

it

intend

to

shield

debtors

from

their

legitimate

liabilities

or

obligations.

But

it

cannot

allow

foreign

corporations

or

entities

which

conduct

regular

business

any

access

to

courts

without

the

fulfillment

by

such

corporation

of

the

necessary

requisites

to

be

subjected

to

our

government's

regulation

and

authority.

By

securing

a

license,

the

foreign

entity

would

be

giving

assurance

that

it

will

abide

by

the

decisions

of

our

courts,

even

if

adverse

to

it."

2

Villanueva,

C.

L.,

&

Villanueva-Tiansay,

T.

S.

(2013).

Philippine

Corporate

Law.

(2013

ed.).

Manila,

Philippines:

Rex

Book

Store.

Philippines shall obtain an amended license in the event it changes its

corporate name, or desires to pursue in the Philippines other or

additional purposes, by submitting an application therefor to the

Securities and Exchange Commission, favorably endorsed by the

appropriate government agency in the proper cases. (n)

G. Effects of Failure to Obtain License:

1. On the Contract Entered Into: Home Insurance Co. v. Eastern

Shipping Lines, 123 SCRA 424 (1983).

Home Insurance Co. v. Eastern Shipping Lines

Facts: S. Kajita & Co., on behalf of Atlas Consolidated Mining &

Development Corporation, shipped on board the SS Eastern Jupiter

(owned by Eastern Shipping Lines) from Osaka, Japan, 2,361 coils of

Black Hot Rolled Copper Wire Rods. The shipment was insured with the

Home Insurance Company against all risks in favor of the recipient of the

shipment, Phelps Dodge Copper Products Corporation of the Philippines

at Manila. The coils discharged from the ship were in bad order. Home

Insurance paid the Phelps Dodge under its insurance policy by virtue of

which Home Insurance became subrogated to the rights and actions of

the Phelps Dodge. Home Insurance made demands for payment against

the Eastern Shipping and the Angel Jose Transportation for

reimbursement of the aforesaid amount but each refused to pay.

Issue: Whether or not Home Insurance, a foreign corporation licensed

to do business at the time of the filing of the case, has the capacity to

sue for claims on contracts made when it has no license yet to do

business in the Philippines.

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

"[t]he

requirement

of

registration

affects

only

the

remedy,"

and

that

"the

lack

of

capacity

at

the

time

of

the

execution

of

the

contracts

was

cured

by

the

subsequent

registration."

1

2. Standing

to

Sue

(Section

133)

Held:

YES.

The

lack

of

capacity

at

the

time

of

the

execution

of

the

contracts

was

cured

by

the

subsequent

registration

is

also

strengthened

by

the

procedural

aspects

of

these

cases.

Home

Insurance

averred

in

its

complaints

that

it

is

a

foreign

insurance

company,

that

it

is

authorized

to

do

business

in

the

Philippines,

that

its

agent

is

Mr.

Victor

H.

Bello,

and

that

its

office

address

is

the

Oledan

Building

at

Ayala

Avenue,

Makati.

These

are

all

the

averments

required

by

Section

4,

Rule

8

of

the

Rules

of

Court.

Home

Insurance

sufficiently

alleged

its

capacity

to

sue.

Doctrine:

The

Corporation

Law

is

silent

on

whether

or

not

the

contract

executed

by

a

foreign

corporation

with

no

capacity

to

sue

is

null

and

Section 133. Doing business without a license.

No foreign corporation transacting business in the Philippines without

a license, or its successors or assigns, shall be permitted to maintain or

intervene in any action, suit or proceeding in any court or

administrative agency of the Philippines; but such corporation may be

sued or proceeded against before Philippine courts or administrative

tribunals on any valid cause of action recognized under Philippine

void ab initio. Still, there is no question that the contracts are

enforceable. The requirement of registration affects only the remedy.

Significantly, Batas Pambansa 68, the Corporation Code of the

Philippines has corrected the ambiguity caused by the wording of

Section 69 of the old Corporation Law.

laws. (69a)

license to do business when one is required, does not affect the

validity of the transactions of such foreign corporation, but

simply removes the legal standing of such foreign corporation to

sue. Although such foreign corporation may still be sued, the

Corporation Code fails to indicate that once sued, if such foreign

corporation can interpose counterclaims in the same suit.2

3. Criminal Liability under Section 144: Home Insurance Co. v.

Section 133 of the present Corporation Code provides that: No

foreign corporation transacting business in the Philippines

without a license, or its successors or assigns, shall be permitted

to maintain or intervene in any action, suit or proceeding in any

court or administrative agency in the Philippines; but such

corporation may be sued or proceeded against before Philippine

courts or administrative tribunals on any valid cause of action

recognized under Philippine laws.

Home Insurance Company therefore held that contracts entered

into by a foreign corporation doing business in the Philippines

without the requisite license remain valid and enforceable and

It seems clearly implied from the languages of both Sections 133

and 134, that the failure of a foreign corporation to obtain a

Eastern Shipping Lines, 123 SCRA 424 (1983).

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

2

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

Section

144.

Violations

of

the

Code.

Violations

of

any

of

the

provisions

of

this

Code

or

its

amendments

not

otherwise

specifically

penalized

therein

shall

be

punished

by

a

fine

of

not

less

than

one

thousand

(P1,000.00)

pesos

but

not

more

than

ten

thousand

(P10,000.00)

pesos

or

by

imprisonment

for

not

less

than

thirty

(30)

days

but

not

more

than

five

(5)

years,

or

both,

in

the

discretion

of

the

court.

If

the

violation

is

committed

by

a

corporation,

the

same

may,

after

notice

and

hearing,

be

dissolved

in

appropriate

proceedings

before

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission:

Provided,

That

such

dissolution

shall

not

preclude

the

institution

of

appropriate

action

against

the

director,

trustee

or

officer

of

the

corporation

responsible

for

said

violation:

Provided,

further,

That

nothing

in

this

section

shall

be

construed

to

repeal

the

other

causes

for

dissolution

of

a

corporation

provided

in

this

Code.

(190

1/2

a)

license, it can sue before Philippine courts on any transaction.

MR. Holdings, Ltd. V. Bajar, 380 SCRA 617 (2002).1

III. Concepts of Doing Business in the Philippines; Effects of Not

Obtaining the License

A. Statutory Concept of Doing Business (R.A. No. 7042, Foreign

Investment Act of 1991).

FOREIGN INVESTMENT ACT OF 1991

Section 3. Definitions.

x x x

4. Summary of Rulings on Doing Business: The principles

regarding the right of a foreign corporation to bring suit in

Philippine courts may thus be condensed in four statements: (1)

if a foreign corporation does business in the Philippines without

d) The praise "doing business" shall include soliciting orders, service

contracts, opening offices, whether called "liaison" offices or

branches; appointing representatives or distributors domiciled in the

Philippines or who in any calendar year stay in the country for a period

or periods totalling one hundred eighty (180) days or more;

participating in the management, supervision or control of any

domestic business, firm, entity or corporation in the Philippines; and

a license, it cannot sue before Philippine courts; (2) if a foreign

corporation is not doing business in the Philippines, it needs no

license to sue before Philippine courts on an isolated

transaction or on a cause of action entirely independent of any

business transaction; (3) if a foreign corporation does business

in the Philippines without a license, a Philippine citizen or entity

which has contracted with said corporation may be estopped

any other act or acts that imply a continuity of commercial dealings or

arrangements, and contemplate to that extent the performance of

acts or works, or the exercise of some of the functions normally

incident to, and in progressive prosecution of, commercial gain or of

the purpose and object of the business organization: Provided,

however, That the phrase "doing business: shall not be deemed to

include mere investment as a shareholder by a foreign entity in

from challenging the foreign corporations corporate personality

in a suit brought before the Philippine courts; and (4) if a foreign

corporation does business in the Philippines with the required

Agilent Technologies Singapore (PTE) Ltd. v. Integrated Silicon Technology

Phil. Corp., 427 SCRA 593 (2004).

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

domestic

corporations

duly

registered

to

do

business,

and/or

the

exercise

of

rights

as

such

investor;

nor

having

a

nominee

director

or

officer

to

represent

its

interests

in

such

corporation;

nor

appointing

a

representative

or

distributor

domiciled

in

the

Philippines

which

transacts

business

in

its

own

name

and

for

its

own

account;

x x x

what constitutes doing business. Case law provides

for the proper interpretation.

Under Section 123 of Corporation Code, a foreign corporation

must first obtain a license and a certificate from the appropriate

government agency before it can transact business in the

Philippines. Where a foreign corporation does business in the

Philippines without the proper license, it cannot maintain any

action or proceeding before Philippine courts as provided in

Section 133 of the Corporation Code. Cargill, Inc. v. Intra Strata

Assurance Corp., 615 SCRA 304 (2010).

The DTI Implementing Rules and Regulations, in defining "doing

business," not only carry the same language as appearing in the

Act, but also includes the following items as not being included

in the term "doing business":

a. The publication of a general advertisement through any

print or broadcast media;

b. Maintaining a stock of goods in the Philippines solely for

the purpose of having the same processed by another

entity in the Philippines;

The Foreign Investments Act of 1991, repealed Articles 44-56 of

Book II of the Omnibus Investments Code of 1987, enumerated

in Section 3(d) not only the acts or activities which constitute

doing business but also those activities which are not deemed

doing business. Cargill, Inc. v. Intra Strata Assurance Corp.,

c. Consignment by a foreign entity of equipment with a

local company to be used in the processing of products

for export;

d. Collecting information in the Philippines; and

e. Performing services auxiliary to an existing isolated

contract of sale which are not on a continuing basis,

such as installing in the Philippines machinery it has

615 SCRA 304 (2010).

o Under Section 3(d) of the Foreign Investments Act of

1991, as supplemented by Rule I, Section 1(f) of its

Implementing Rules and Regulations, the appointment

of a distributor in the Philippines is not sufficient to

constitute doing business unless it is under the full

control of the foreign corporation. In the same manner,

if the distributor is an independent entity which buys

and distributes products, other than those of the

foreign corporation, for its own name and its own

account, the latter cannot be considered to be doing

business in the Philippines. Steelcase, Inc. v. Design

International Selections, Inc., 670 SCRA 64 (2012).

Atty. Hofilea The Foreign Investments Act of 1991

provided the standards and/or guidelines for identifying

manufactured or exported to the Philippines, servicing

the same, training domestic workers to operate it, and

similar incidental services.

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

B.

Jurisprudential

Concepts

of

Doing

Business:

It

implies

a

continuity

of

commercial

dealings

and

arrangements

and

the

performance

of

acts

or

works

or

the

exercise

of

some

of

the

functions

normally

incident

to

the

purpose

or

object

of

a

foreign

corporations

organization.

Mentholatum

v.

Mangaliman,

72

Phil.

525

(1941).

The characterization by Mentholatum of "doing business" in the

Philippines covers transactions or series of transactions in

pursuit of the main business goals of the corporation, and done

with intent to continue the same in the Philippines. 1

1. Twin

Characterization

Test.2

a. Nature

of

the

act

or

transaction:

the

performance

of

acts

or

works

or

the

exercise

of

some

of

the

functions

normally

incident

to,

and

in

progressive

prosecution

of

the

purpose

and

object

of

its

organization

and

considered

as

the

true

test

of

doing

business

in

the

Philippines

is

whether

a

foreign

corporation

is

maintaining

or

continuing

in

the

Philippines

"the

body

or

substance

of

the

business

or

enterprise

for

which

it

was

organized

or

whether

is

has

substantially

retired

from

it

and

turned

it

over

to

another.

b. Existence

of

Continuing

Intent:

In

doing

the

act

or

transaction

there

was

an

intent

on

the

part

of

the

foreign

corporation

to

undertake

a

continuity

of

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

2

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

commercial dealings and arrangement in the Philippines

as to distinguish it from an isolated transaction.

Mentholatum v. Mangaliman

Facts: The Mentholatum Co., Inc., is a Kansas corporation which

manufactures "Mentholatum," a medicament and salve for the

treatment of irritation and other external ailments of the body. The

Philippine-American Drug Co., Inc. is its exclusive distributing agent in

the Philippines authorized by it to look after and protect its interests. On

26 June 1919 and on 21 January 1921, the Mentholatum Co., Inc.,

registered with the Bureau of Commerce and Industry the word,

"Mentholatum", as trademark for its products.

The Mangaliman brothers prepared a medicament and salve named

"Mentholiman" which they sold to the public packed in a container of

the same size, color and shape as "Mentholatum." As a consequence,

Mentholatum, etc. suffered damages from the diminution of their sales

and the loss of goodwill and reputation of their product in the market.

On 1 October 1935, the Mentholatum Co., Inc., and the Philippine-

American Drug, Co., Inc. instituted an action in the Court of First

Instance (CFI) of Manila against Anacleto Mangaliman, Florencio

Mangaliman and the Director of the Bureau of Commerce for

infringement of trademark and unfair competition.

Issue: Whether or not Mentholatum, etc. could prosecute the instant

action without having secured the license required in Section 69 of the

Corporation Law.

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

activity

undertaken

in

the

Philippines

amounts

to

doing

business

as

to

require

the

foreign

corporation

to

obtain

such

license.1

o Isolated

transactions,

even

when

perfected

and/or

consummated

within

Philippine

territory,

do

not

constitute

doing

business

in

the

Philippines,

and

do

not

constitute

the

essential

element

of

presence

Held: NO. Mentholatum Co., Inc., being a foreign corporation doing

business in the Philippines without the license required by section 68 of

the Corporation Law, it may not prosecute this action for violation of

trade mark and unfair competition. Neither may the Philippine-

American Drug Co., Inc., maintain the action here for the reason that

the distinguishing features of the agent being his representative

character and derivative authority, it cannot now, to the advantage of

its principal, claim an independent standing in court.

Doctrine: No general rule or governing principle can be laid down as to

what constitutes "doing" or "engaging in" or "transacting" business.

Indeed, each case must be judged in the light of its peculiar

required under due process considerations. The legal

basis by which local courts can legally obtain jurisdiction

over the person of a foreign corporation on an isolated

transaction would be consent or the voluntary

surrender of tis person to the jurisdiction of the courts.2

environmental circumstances. The true test, however, seems to be

whether the foreign corporation is continuing the body or substance of

the business or enterprise for which it was organized or whether it has

substantially retired from it and turned it over to another. The term

implies a continuity of commercial dealings and arrangements, and

contemplates, to that extent, the performance of acts or works or the

exercise of some of the functions normally incident to, and in

incidental or casual but indicates the foreign corporation's

intention to do other business in the Philippines, said single act

or transaction constitutes doing business. Far East Int'l. v.

Nankai Kogyo, 6 SCRA 725 (1962).

o It is not really the fact that there is only a single act

done that is material for determining whether a

corporation is engaged in business in the Philippines,

since other circumstances must be considered. Where a

single act or transaction of a foreign corporation is not

merely incidental or casual but is of such character as

distinctly to indicate a purpose on the part of the

foreign corporation to do other business in the state,

progressive prosecution of, the purpose and object of its organization.

2. Single Transaction Whether a foreign corporation needs to

obtain a license, and fails to do so, whether it should be denied

legal standing to obtain remedies from local courts and

administrative agencies, depends therefore on the issue

whether it will engage in business in the Philippines. Not every

Where a single act or transaction, however, is not merely

such act will be considered as constituting business.

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

2

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

Litton

Mills,

Inc.

v.

Court

of

Appeals,

256

SCRA

696

(1996).

Participating in a bidding process constitutes doing business

because it shows the foreign corporations intention to engage

in business in the Philippines. In this regard, it is the

performance by a foreign corporation of the acts for which it

was created, regardless of volume of business, that determines

whether a foreign corporation needs a license or not.

European Resources and Technologies, Inc. v. Ingenieuburo

Birkhanh + Nolte, 435 SCRA 246 (2004).

Atty. Hofilea At the moment, the Court has ruled

that at the time one bids, you need to have a license

under the presumption that you bid because you want

to pursue your business here. Disagrees, because the

act of doing business begins when you actually win the

bidding.

3. Territoriality Rule (Contract Test1)

o

To be doing business in the Philippines requires that the

contract must be perfected or consummated in Philippine soil. A

c.i.f. West Coast arrangement makes delivery outside of the

Philippines. Pacific Vegetable Oil Corp. v. Singson, Advanced

Decision Supreme Court, April 1955 Vol., p. 100-A; Aetna

Casualty & Surety Co. v. Pacific Star Line, 80 SCRA 635 (1977).2

Pacific

Vegetable

Oil

Corp.

v.

Singson

Villanueva, C. L., & Villanueva-Tiansay, T. S. (2013). Philippine Corporate Law.

(2013 ed.). Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store.

2

Universal Shipping Lines, Inc. v. IAC, 188 SCRA 170 (1990).

Facts: Pursuant to a contract, Angel Singzon promised to sell to Pacific

Vegetable Oil Corporation, a foreign corporation, copra. Singzon failed

to deliver, but promised to do so in the amicable settlement it executed

with Pacific. Failure would entitle Pacific to damages from Singzon.

However, Singzon again failed to deliver and announced by telegram

that he would not be able to ship said copra. As such, Pacific filed for

damages but Singzon filed a motion to dismiss on the ground that

Pacific failed to obtain a license to transact business in the Philippines

and consequently, it had no personality to file the action. The trial court

held that Pacific had no personality to institute the present case even if

it afterwards obtained a license to transact business upon the theory

that this belated act did not have the effect of curing the defect that

existed when the case was instituted.

Issue: Whether or not Pacific can maintain the present action

Held: YES. The agreement between Singzon and Pacific was c.i.f. Pacific

Coast. This means that the vendor was to pay not only the cost of the

goods, but also the freight and insurance expenses and, as it was

judicially interpreted, this is to indicate that the delivery is to be made

at the port of destination. It follows that the appellant corporation has

not transacted business in the Philippines in contemplation of Section

68 and 69 of the Corporation Law. It appearing that appellant

corporation has not transacted business in the Philippines and as such is

not required to obtain a license before it could have personality to bring

a court action, it may be stated that said appellant, even if a foreign

corporation, can maintain the present action because as aptly said by

this Court, it was never the purpose of the Legislature to exclude a

foreign corporation which happens to obtain an isolated order for

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

business

from

the

Philippines,

from

securing

redress

in

the

Philippine

courts,

and

this,

in

effect,

to

permit

persons

to

avoid

their

contracts

made

with

such

foreign

corporation.

Doctrine:

CLV

OPINION:

The

Pacific

Vegetable

Oil

doctrine

does

consider

Defendants

refused

to

pay

for

the

damage,

so

the

surety

company

paid.

Defendants

Manila

Port

Service

and

Manila

Railroad

Company,

Inc.

alleged

that

the

plaintiff,

Aetna

casualty

&

Surety

Company,

is

a

foreign

corporation

not

duly

licensed

to

do

business

in

the

Philippines

and,

the twin characterization tests of Mentholatum of substance of the

transactions pertaining to the main business and the continuity or intent

to continue such activities. It would seem that even if the twin

characterization tests of Mentholatum obtained in a case, under the

Pacific Vegetable doctrine, so long as the perfection and consummation

of a series of transactions are done outside the Philippine jurisdiction,

the same would not constitute doing business in the Philippines, even if

therefore without capacity to sue and be sued. This was supported by

certifications from the Office of the Insurance Commission and the

Securities and Exchange Commission showing that the Aetna Casualty

and Surety Company has not been licensed nor incorporated to do

business in the Philippines as foreign corporation. The trial court ruled

against surety company on the ground that it has been doing business in

numerous the Philippines contrary to Philippine laws.

the products themselves should be manufactured or processed in the

Philippines by locals. The implication of this doctrine is that if the salient

points of a contract do not find themselves in the Philippines, Philippine

authorities have no business subjecting the parties to local registration

and licensing requirements.

Issue:

Whether

or

not

the

appellant,

Aetna

Casualty

&

Surety

Company,

has

been

doing

business

in

the

Philippines.

Held:

NO.

It

is

merely

collecting

a

claim

assigned

to

it

by

the

consignee,

it

is

not

barred

from

filing

the

instant

case

although

it

has

not

secured

a

license

to

transact

insurance

business

in

the

Philippines.

While

plaintiff

Aetna

Casualty

&

Surety

Co.

v.

Pacific

Star

Line

Facts:

I.

Shalom

&

Co.

Inc.

were

supposed

to

receive

a

shipment

of

goods

carried

on

board

SS

Ampal

whose

operator

was

Pacific

Star

Line.

The

Bradman

Co.

Inc.,

was

the

ship

agent

in

the

Philippines

for

the

SS

Ampal,

while

the

Manila

Railroad

Co.

Inc.

and

Manila

Port

Service

were

the

arrastre

operators

in

the

port

of

Manila

and

were

authorized

to

delivery

cargoes

discharged

into

their

custody.

Aetna

Surety

Casualty

&

Surety

Co.

Inc.

insured

the

cargo

in

for

I.

Shalom.

The

SS

Ampal

arrived

in

Manila

but

due

to

the

negligence

of

the

defendants,

the

shipment

sustained

damages

representing

pilferage

and

seawater

damage.

is a foreign corporation without license to transact business in the

Philippines, it does not follow that it has no to bring the present action.

Such license is not necessary because it is not engaged in business in the

Philippines.

Doctrine: Object of Sections 68 and 69 of the Corporation Law was not

to prevent the foreign corporation from performing single acts, but to

prevent it from acquiring a domicile for the purpose of business without

taking the steps necessary to render it amenable to suit in the local

courts. It was never the purpose of the Legislature to exclude a foreign

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

business.

standard

in

the

FIA

requires

physical

presence

Issue:

What

about

in

the

time

of

internet

and

telephone

solicitations

where

there

is

no

physical

presence

in

the

state?

4. Transactions

Seeking

Profit

Although

each

case

must

be

corporation which happens to obtain an isolated order for business

from the Philippines, from securing redress in the Philippine courts.

o

To be transaction business in the Philippines for

purposes of Section 133 of the Corporation Code, the

foreign corporation must actually transact business in

the Philippines, that is, perform specific business

transactions within the Philippine territory on a

continuing basis in its own name and for its own

account. B. Van Zuiden Bros., Ltd v. GTVL

Manufacturing Industries, Inc., 523 SCRA 233 (2007),

citing VILLANUEVA, PHILIPPINE CORPORATE LAW 813

judged in light of its attendant circumstances, jurisprudence has

evolved several guiding principles for the application of these

tests. By and large, to constitute doing business, the activity

to be undertaken in the Philippines is one that is for profit-

making. Agilent Technolgies Singapore (PTE) Ltd. v. Integrated

Silicon Technology Phil. Corp., 427 SCRA 593 (2004), citing

VILLANUEVA, PHILIPPINE CORPORATE LAW 596 et seq. (1998

(2001).

ed.);

Cargill,

Inc.

v.

Intra

Strata

Assurance

Corp.,

615

SCRA

304

(2010),

citing

VILLANUEVA,

PHILIPPINE

CORPORATE

LAW

801-

802

(2001).

Exception: Acts of Solicitations Solicitation of business

contracts constitutes doing business in the Philippines.

Marubeni Nederland B.V. v. Tensuan, 190 SCRA 105.

Examples: (Atty. Hofilea)

o Where a domestic corporation initiated a supply

agreement with a foreign corporation and all of it was

executed abroad, there is no doing business because

there no act of solicitation on the part of the foreign

company and in accordance with the territoriality rule,

none of it happened here.

o

Where the negotiations happened here upon request of

the domestic corporation, that is still not doing

business within the contemplation of the law.

Where the foreign corporation sends a representative

to approach a domestic corporation to offer a

transaction, such would be considered as doing

Agilent Technolgies Singapore (PTE) Ltd. v. Integrated Silicon

Technology Phil. Corp

Facts: Integrated Silicon entered into a Value Added Assembly Services

Agreement ("VAASA"), with HP-Singapore. Under the contract,

Integrated Silicon was to locally manufacture and assemble fiber optics

for export to HP-Singapore, who in turn would provide raw materials

and machinery and pay Integrated Silicon the purchase price of the

finished products. The VAASA had a five-year term, with a provision for

annual renewal by mutual written consent. In 1999, with the consent of

Integrated Silicon, HP-Singapore assigned all its rights and obligations in

the VAASA to Agilent. Agilent is not licensed to do business here.

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

In

2001,

Integrated

Silicon

filed

a

complaint

for

"Specific

Performance

and

Damages"

against

Agilent,

alleging

that

Agilent

breached

the

parties

oral

agreement

to

extend

the

VAASA.

Agilent

filed

a

separate

replevin

case

against

Integrated

Silicon,

praying

that

the

defendants

be

transaction or on a cause of action entirely independent of any

business transaction;

3. If a foreign corporation does business in the Philippines without

a license, a Philippine citizen or entity which has contracted

with said corporation may be estopped from challenging the

ordered to immediately return its equipment, machineries and the

materials to be used for fiber-optic components which were left in the

plant of Integrated Silicon. Integrated Silicon argues that since Agilent is

an unlicensed foreign corporation doing business in the Philippines, it

lacks the legal capacity to file suit. The replevin case was dismissed.

Issue: Whether or not the Agilent has legal capacity to sue.

foreign corporations corporate personality in a suit brought

before Philippine courts; and

4. If a foreign corporation does business in the Philippines with the

required license, it can sue before Philippine courts on any

transaction.

Held:

YES.

By

the

clear

terms

of

the

VAASA,

Agilents

activities

in

the

Philippines

were

confined

to

(1)

maintaining

a

stock

of

goods

in

the

Philippines

solely

for

the

purpose

of

having

the

same

processed

by

Integrated

Silicon;

and

(2)

consignment

of

equipment

with

Integrated

Silicon

to

be

used

in

the

processing

of

products

for

export.

As

such,

we

hold

that,

based

on

the

evidence

presented

thus

far,

Agilent

cannot

be

deemed

to

be

"doing

business"

in

the

Philippines.

As

a

foreign

corporation

not

doing

business

in

the

Philippines,

it

needed

no

license

before

it

can

sue

before

our

courts.

Doctrine:

The

principles

regarding

the

right

of

a

foreign

corporation

to

bring

suit

in

Philippine

courts

may

be

condensed

in

four

statements:

1. If

a

foreign

corporation

does

business

in

the

Philippines

without

a

license,

it

cannot

sue

before

the

Philippine

courts;

2. If

a

foreign

corporation

is

not

doing

business

in

the

Philippines,

it

needs

no

license

to

sue

before

Philippine

courts

on

an

isolated

NOTES

BY

RACHELLE

ANNE

GUTIERREZ

(UPDATED

APRIL

3,

2014)

Examples:

o

Insurance Business A foreign corporation with a

settling agent in the Philippines which issues twelve

marine policies covering different shipments to the

Philippines is doing business in the Philippines. General

Corp. of the Phil. v. Union Insurance Society of Canton,

Ltd., 87 Phil. 313 (1950).

A foreign corporation which had been collecting

premiums on outstanding policies is doing business in

the Philippines. Manufacturing Life Ins. v. Meer, 89

Phil. 351 (1951).

Air Carriers Off-line air carriers having general sales

agents in the Philippines are engaged in business in the

Philippines and that their income from sales of passage

here (i.e., uplifts of passengers and cargo occur to or

from the Philippines) is income from within the

Philippines. South African Airways v. Commissioner of

Internal Revenue, 612 SCRA 665 (2010).

CORPORATION LAW REVIEWER (2013-2014)

ATTY. JOSE MARIA G. HOFILEA

Exception: Transactions with Agents and Brokers Granger

Associates v. Microwave Systems, Inc., 189 SCRA 631 (1990).1

Granger

Associates

v.

Microwave

Systems,

Inc.

Facts:

Granger

Associates

(foreign

corporation)

sued

Microwave

Systems,