Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Art 614

Uploaded by

dynutza0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views9 pagesThe relationship between task performance and frequency of posttask excuses was compared with that between performance level and frequency of Anticipatory Excuses made before performance was measured. There was a weak inverse correlation between excuse frequency and expected, but not with actual exam scores. Excuses ARE A FORM OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT (schlenker, 1980; Scott and Lyman, 1968) that people use to extricate themselves from actions for which they may otherwise be blamed or punished.

Original Description:

Original Title

Art 614(2)

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe relationship between task performance and frequency of posttask excuses was compared with that between performance level and frequency of Anticipatory Excuses made before performance was measured. There was a weak inverse correlation between excuse frequency and expected, but not with actual exam scores. Excuses ARE A FORM OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT (schlenker, 1980; Scott and Lyman, 1968) that people use to extricate themselves from actions for which they may otherwise be blamed or punished.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views9 pagesArt 614

Uploaded by

dynutzaThe relationship between task performance and frequency of posttask excuses was compared with that between performance level and frequency of Anticipatory Excuses made before performance was measured. There was a weak inverse correlation between excuse frequency and expected, but not with actual exam scores. Excuses ARE A FORM OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT (schlenker, 1980; Scott and Lyman, 1968) that people use to extricate themselves from actions for which they may otherwise be blamed or punished.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

The Journal of Psychology, 121(5), 413-421

Anticipatory Excuses in Relation to

Expected versus Actual Task Performance

JOHN JUNG

Department of Psychology

California State University

ABSTRACT. The relationship between task performance and frequency of posttask

excuses was compared with that between performance level and frequency of antic-

ipatory excuses made before performance was measured on a classroom exam. Study

T used a checklist of 10 statements frequently used by students as excuses for poor

performances on examinations and students indicated which statements applied to

them. The relationships between excuse frequency, actual performance, and ex-

pected performance (relative to classmates) were measured either before or after the

first midterm exam for two subgroups. There was a weak inverse correlation between

excuse frequency and expected, but not with actual exam scores. Expected scores

were uncorrelated with actual exam scores. Anticipatory excuses were less frequent

than posttest excuses, whereas expectations about performance were higher before

than immediately after the test. Study 2 was based on the second exam of the semes-

ter to enable students to have a better basis for their expectations. An open-ended

format was used to allow students to express a wider variety of excuses. Accounts

were obtained for higher (justification) as well as lower (excuse) expected scores,

Expectations of poorer performance led to more anticipatory excuses whereas ex-

pected improved scores were correlated with more pretest justifications. Thus, even

though students are poor predictors of actual performance, the relationship between

frequency of anticipatory excuses and expected performance parallels that obtained

for excuses made after task performance.

EXCUSES ARE A FORM OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT (Schlen-

ker, 1980; Scott & Lyman, 1968) that people use to extricate themselves from

actions for which they may otherwise be blamed or punished. Most research

on excuses (Snyder, Higgins, & Stucky, 1983) has been on postperformance

Requests for reprints should be sent to John Jung, Department of Psychology, Cali-

‘fornia State University, 1250 Bellflower Blvd., Long Beach, CA 90840.

413

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

416 __ The Journal of Psychology

excuses when the shortcoming has already occurred. When excuses are of-

fered after a poor performance or a transgression, there may be less blame

and retribution from others (Snyder et al., 1983).

However, excuses are also often made prior to task performance, perhaps

because they may offset the embarrassment and other adverse consequences

expected to occur from an expected failure. Thus, they may serve the same

function as postperformance excuses. By making advance excuses, there may

be less embarrassment or retribution than if excuses were made after the fail-

ing. The excuse-maker can claim, “I told you so” when the performance turns

‘out to be inadequate.

Whereas it is clear that excuses made after poor performance may be

motivated by impression management concerns (Schlenker, 1980), anticipa-

tory excuses may prove superfluous if eventual performance is actually ade-

quate. However, because students are often unable to predict their test out-

comes accurately, anticipatory excuses may still occur. One hypothesis is that

anxiety prior to an exam may lead to excuses as a type of nervous activity. If

this is the primary basis for anticipatory excuses, they should bear little rela-

tionship to actual performance.

Another explanation is that anticipatory excuses are a type of coping

strategy in the event of failure. Making excuses in advance of poor perform-

ance may be regarded as more credible to observers than those offered later,

which might be discredited as just “excuses.” Furthermore, if the poor per-

formance does not occur, the student may be perceived as modest for having

made so many unnecessary advance excuses. Consequently, anticipatory ex-

cuses may be made even if the person really does not expect failure because

there may be little to lose and much to gain.

Study 1

The study of naturally occurring excuses is difficult because a sufficient num-

ber of occurrences may require a lengthy period of observation. One situation

that avoids this problem is used in the present set of studies, which examines

anticipatory excuses in an evaluative situation—classroom examinations.

Even though students often may not know how good their actual per-

formance will be, they usually have expectations. If anticipatory excuses are

made to protect self-esteem in the face of expected poor levels of perform-

ance, there should be an inverse correlation between expected performance

and frequency of anticipatory excuses.

In the present study, students were asked to predict their test score and

then asked to check off a list of common excuses that they believed might

account for their expected performance. Students who expected to do as well

or better than average would not be expected to check many excuses whereas

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

Jung__415

those who expected to do lower than average would. This study involves a

comparison of anticipatory and postperformance excuse frequency with ex-

pected and actual test performance.

Method

Subjects and procedure. A class of 144 students (58 males and 86 females)

in an introductory psychology course served as subjects. Exams with either a

pretest or a posttest of expected performance and excuses were placed on

alternate desks in the lecture hall. This procedure was designed to create two

equal groups, but, unfortunately, students did not occupy the seats in se-

quence, with the result being that 86 students received pretests and only 58

had posttests

Marerials. A list of common excuses that have been received by instructors

was obtained by informal interviews of three instructors:

I did not study enough

I did not have enough time to study.

The test was not fair.

Today is not my lucky day.

I feel a bit sick today.

1 did not sleep well.

The text was not well written.

Lectures were too difficult.

I’m too tense and nervous.

Other: (specify)

Seeravayne

Procedure. On the pretest, students checked off as many of the statements on

the list of excuses that they believed applied to them and rated their expected

performance relative to classmates on a 5-point scale before taking the test.

For the posttest group, immediately after completing the exam, the same

questionnaire was given to obtain their expected performance and to identify

which statements on the list of excuses applied to them. The term excuses

was not used to describe the list to the students. The exam had 100 multiple-

choice items and was the first of three exams for the semester.

Results

As indicated in Table 1, the mean exam score was 66.7 for the pretest excuse

group and 64.7 for the posttest excuse group, which was not significant,

1(142) < 1.0. The mean number of excuses was not significantly different for

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

416 The Journal of Psychology

TABLE 1

Means and Correlations for Pretest, Posttest,

and Postfeedback Measures

———

Pretest group Posttest group.

Measure, 1 2 3 1 2 3

Expectancy

Excuses ~.27 —.26

Exam Score 48 — 12 AL AS

Mean 2.88 1.30 66.7 2.65 1.53 64.7

Note. 1 = Expectancy, 2 = Excuses, and 3 = Exam Score.

the posttest group, 1.53, and the pretest group, 1.30, (142) = 1.1, ns. How-

ever, the mean expectations regarding exam scores were higher for the pretest

group than for the posttest group (2.88 vs. 2.65), (142) = 1.73, p < .05.

Significant correlations were found between actual exam scores and pre-

test and posttest expectations, r(84) = .48, p < .001 and 7(56) = .41,

p < 001, respectively, but they did not differ from each other, Fisher's exact

Z = 52.

For the pretest group, small correlations were found between excuse fre-

quency and expected performance, r(84) = ~.27, p < .01, and between

excuses and actual exam scores, r(84) = —12, p > .05, and they did not

differ from each other, Fisher's exact Z = 1.1

In the posttest group, excuse frequency and expected performance were

weakly related, (56) = —.26, p < .01, as were excuses and actual exam

scores, (56) = —.15, ns. The difference between the two correlations was

not significant, Fisher's exact Z = .55.

The pretest excuses given by students most frequently fell into only a

few types: “not enough study” (38%), not enough time to study (19%), and

psychological problems such as anxiety or personal problems (23%). Table 2

shows similar patterns of excuses for the pre- and posttest excuse groups al-

though there were higher levels for “lack of study” and “amount of time to

study” for the posttest group.

Discussion

‘The evidence indicates slight support for the prediction that either type of

excuses, anticipatory or postperformance, will occur more often for students

expecting to do poorly on an exam, as implied by theories about excuses

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

tt

(Snyder et al., 1983). One reason for such weak findings may be that students

were limited to the excuses on the checklist. Furthermore, the power of sug-

gestion may operate so that more excuses might be selected from the checklist

than would spontaneously occur, which might mask any relationships.

To avoid these possibilities, Study 2 used an open-ended format that

asked students how they would account for their expected performance on an

exam. Only pretest measures were taken in Study 2.

The relationship obtained in Study 1 may also have been weak because

it involved the first exam of the semester so it was not possible for students to

base their expectations on any valid information about this specific course

and/or instructor. Thus, the relationship obtained between excuses and per-

formances may have been weakened. A stronger effect should occur for situ-

ations where students have more information about the class and have a more

realistic basis for forming expectations. Therefore, in Study 2 the question-

naire preceded the second test of the semester so students had some realistic

expectation about their ability and the instructor's tests. Another difference

between the two studies was that in Study 2 the judgment requested of sub-

jects was how well they expected to do relative to the first exam rather than

hhow well they would do relative to classmates, as in Study 1.

Finally, Study 2 was expanded to examine what type of anticipatory ac-

counts (explanations) are made for expected high performance rather than

only low performance. One would not expect “excuses” to be offered for

expected high performance. Impression management theory (Schlenker,

1980) suggests that persons who expect to do well might wish to receive

credit and recognition by “‘acclaiming” or giving reasons why they will do

well. Success has been attributed to internal and stable factors such as effort

TABLE 2

Percentage of Subjects Giving Each Excuse for Study 1

ee

Excuse Pretest Posttest

Not study enough 38 33

Not enough time to study 19 38

‘The test was not fair 1 2

‘Not my lucky day 3 5

Feel a bit sick today 10 6

I did not sleep well 9 2

Text was not well written 2 0

Lectures too difficult 0 °

Too tense and nervous B 7

Other 16 7

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

48 _ The Journal of Psychology

and ability (Weiner, 1974; Zuckerman, 1979). Finally, students who expected

to do about the same as on the first test should give neither excuses nor justi-

fications unless possibly they expect to repeat very high or very low scores.

Study 2

Method

Subjects and materials. A class of 152 introductory psychology students (48

males and 104 females served as subjects. A 100-item, multiple-choice exam

covering the course material was used in a 1-hr class period.

Instructions. Before the test, students were asked to predict their performance

relative to their score on the first exam. They were also asked to recall their

first exam score. Then they were asked to briefly explain why they expected

such an outcome.

Scoring. Two judges read the accounts offered for performance. If the account

implied that expected performance could have been better due to some factor

lowering performance, it was scored as an excuse. A justification was counted

if the account implied that some factor led to high or higher than expected

performance. The two independent judges were able to agree on all protocols.

Results

Only 81% of the subjects provided ratings of expected outcome, possibly

because they were more concerned with taking the exam. In comparison to

the first test, most of these students (45%) expected to do better, whereas

another large percentage (36%) expected to do about the same, and only a

small percentage (20%) expected to do worse than before, with the mean

expectation being 3.19 on the 5-point scale.

Table 3 indicates that the expected performance for the test was unrelated

with actual performance, r(150) = .04, ns, and the number of excuses was

unrelated with actual performance, r(150) = ~.03, ns. The number of jus-

tifications was slightly correlated with performance, r(150) = .19, p < .01.

The mean number of excuses was only .15, indicating that many did not

offer any excuses at all. However, the number of anticipatory excuses was

inversely correlated, r(150) = ~.60, p < .01, with expected performance,

as predicted, to a greater extent than in Study I.

‘Actual scores on first test were inversely related, r(150) = ~.20 p <

01, with expected scores for the second test. Apparently, students believe in

the “law of averages” such that those who did very poorly expected to im-

prove whereas those who did very well expected to fall back toward the mean.

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

een ne eee cee

TABLE 3

‘Means and Correlations for Pretest Expectations,

Accounts, and Second Exam Scores

———

Second

Expectations Excuses _—_Justifications exam

Expectations

Excuses -.60

Justification 4 —.20

Second exam —.04 03, 19

Means 3.19 15 49 59.5

The mean score was 61.5 on the first exam, and 59.5 on the second. The

correlation between the two tests was moderately high, r(150) = .58,

p<.0l.

‘The most common excuses offered by those expecting to do lower on the

second exam than on the first exam were “not enough study" or “not enough

study time available” (25%), material difficulty (12%), illness and lack of

motivation (12%), and an excuse, not included in the list used in Studies 1

and 2, “several exams on the same day” (16%).

‘The mean number of justifications was .49. Frequency of justifications

was positively associated, r(150) = .54, p < .01, with expected scores, as

predicted. Justification and excuses had a weak inverse relationship, r(150)

= ~.20,p < 01.

Common justifications for expected higher scores on the second exam

were effort-related such as “TI studied a lot” (44%) or related to use of a better

method of study (24%). Another explanation for higher expectations involved

“experience” such as knowing what kinds of tests to expect (10%)

When expected performance was for “about the same,” the justification

was often based on the expenditure of equivalent amount of study (52%) for

both exams. If low performance was expected to be repeated on the second

exam, excuses usually involved “insufficient study” (37%)

Many subjects (33%) could not recall their actual first exam score, and

another 12% reported a letter grade rather than a numerical score. Thus, they

‘were not included in computing the correlation of the actual first exam score

and the recalled score, which was significant r(75) = .82, p < .01. Due to

this loss of subjects, there was concer that subjects who could not accurately

recall their first test scores might not make meaningful predictions about their

second exam performance relative to their first exam scores. Therefore, the

preceding analyses were repeated for this subgroup. However, the pattern of

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

420 __ The Journal of Psychology

correlations was highly similar with those reported for the whole sample and

are not presented here.

Discussion

Although open-ended excuses were relatively infrequent, possibly due to the

greater effort to report them, the results of Study 2 more convincingly show

that more anticipatory excuses occurred for those who expected lower scores,

whereas the number of excuses was not related to actual performance. Over-

all, the findings agree with the formulation of Snyder et al. (1983) that antic

ipatory excuses occur when the individual expects to do poorly.

One advantage of anticipatory excuses over postperformance excuses

may be that the latter will be perceived by others as “excuses” whereas the

former might even be seen as a form of modesty. If the poor performance

materializes, the person can say “I told you so” and minimize blame; if good

performance occurs, the anticipatory excuses would be likely to be perceived

as modesty. This process might account for the use of excuses as a form of

self-handicapping (Jones & Berglas, 1978) in which excuses might lower mo-

tivation or performance. One possibility is that anticipatory excuses are strat-

egies that backfire and become self-fulfilling or self-handicapping (Jones &

Berglas, 1978; Smith, Snyder, & Handelsman, 1982). However, itis possible

that for some individuals or situations, the act of making anticipatory excuses

could reduce anxiety and hence ironically facilitate performance. In interper-

sonal competition situtations where one’s performance is relative to that of

others, anticipatory excuses might create an advantage by lulling opponents

into false confidence. Unfortunately, correlational evidence of the type in this

study is inadequate to address these intriguing questions about the effects of

anticipatory excuses.

In addition, Study 2 provides evidence that when students expect to do

much better, the frequency of anticipatory explanations or justifications is

related to expected performance level and to a weak extent, with higher actual

scores. In line with attribution theories (Weiner, 1974), attributions for suc-

cess involve attributions to effort and ability; in contrast, the accounts for

expected poor performance were often in terms of external circumstances

such as extenuating factors.

REFERENCES

Jones, E., & Berglas, S. (1978). Control of attributions about the self through self-

handicapping strategies: The appeal of alcohol and the role of underachievement.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4, 200-206.

Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management: The self-concept, social identity,

‘and interpersonal relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

Jung 421

Scott, M. B., & Lyman, S. M. (1968). Accounts. American Sociological Review,

33, 46-62,

‘Smith, T. W., Snyder, C. R., & Handelman, M. M. (1982). On the self-serving

function of an academic wooden leg: Test anxiety as a self-handicapping strategy.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 314-321.

Snyder, C. R., Higgins, R. L., & Stucky, R. J. (1983). Excuses: Masquerades in

search of grace. New York: Wiley.

Weiner, B. (Ed.). (1974). Achievement motivation and attribution theory. Morris-

town, NJ: General Leaning Press.

Zuckerman, M. (1979). Attributions of success and failure revisited, or: The moti-

vational bias is alive and well in attribution theory. Journal of Personality, 47,

245-287.

Received April 23, 1987

Copyright © 2001. All Rights Reserved.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Tommee Tippee 1072 Bottle Warmer PDFDocument19 pagesTommee Tippee 1072 Bottle Warmer PDFdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Tommee Tippee 1072 Bottle Warmer PDFDocument19 pagesTommee Tippee 1072 Bottle Warmer PDFdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Big Bugs 1Document79 pagesBig Bugs 1dynutza100% (1)

- Kenken Puzzle First 7Document15 pagesKenken Puzzle First 7dynutzaNo ratings yet

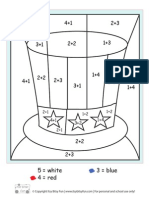

- Space Addition and Subtraction Puzzle: Subtract and Add The Numbers To Find Out Which Colour To UseDocument1 pageSpace Addition and Subtraction Puzzle: Subtract and Add The Numbers To Find Out Which Colour To UsedynutzaNo ratings yet

- Kenken Puzzle First 7Document15 pagesKenken Puzzle First 7dynutzaNo ratings yet

- Coloring LeafDocument5 pagesColoring LeafdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Product Data Sheet Toepfer Whole Grain Oat Cereal PDFDocument1 pageProduct Data Sheet Toepfer Whole Grain Oat Cereal PDFdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Big Bugs 1Document62 pagesBig Bugs 1dynutzaNo ratings yet

- Mate Pescuieste Rez PDFDocument35 pagesMate Pescuieste Rez PDFdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Kenken Puzzle First 7 PDFDocument2 pagesKenken Puzzle First 7 PDFdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Kenken Puzzle First 7 PDFDocument2 pagesKenken Puzzle First 7 PDFdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Classroom Word SearchDocument2 pagesClassroom Word SearchdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Classroom Word SearchDocument2 pagesClassroom Word SearchdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Connect Dots ShipDocument1 pageConnect Dots ShipdynutzaNo ratings yet

- Adunare Colorat Dupa NumarDocument3 pagesAdunare Colorat Dupa NumardynutzaNo ratings yet

- Classroom Word SearchDocument1 pageClassroom Word SearchAndreea BozianNo ratings yet

- Play Sentence Scramble: What You NeedDocument1 pagePlay Sentence Scramble: What You NeeddynutzaNo ratings yet

- Play Sentence Scramble: What You NeedDocument1 pagePlay Sentence Scramble: What You NeeddynutzaNo ratings yet

- An In-Depth Look at Digital DocumentsDocument292 pagesAn In-Depth Look at Digital DocumentsAndrei BudalaceanNo ratings yet

- Ego-Depletion - Is It All in Your HeadDocument28 pagesEgo-Depletion - Is It All in Your HeadcsuciavaNo ratings yet

- Posturi MECTSDocument1 pagePosturi MECTSdynutzaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)