Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Education 830 Assignment A

Uploaded by

api-42688552Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Education 830 Assignment A

Uploaded by

api-42688552Copyright:

Available Formats

EDUCATION 830 ASSIGNMENT A INTRODUCTION

Pagtakhan 1

I was recently preparing my students for the Social Studies 11 June provincial exam. The exam consists of two parts, fifty or so multiple choice questions and two essays. In the spirit of being an effective teacher, when my students asked for examples of the kinds of essay questions these tests tend to ask, I dutifully complied. One question, that never struck me as unusual before, did that that day. It began with the following quote, Despite British and American influences Canada has evolved into an autonomous nation. It then asked students to evaluate the statement with examples from 1914-2000. (Ministry of Education, 2005). Only now, as I reflect on the readings of educational theorists such as Chet Bowers, David Orr, and Paolo Frere along with taking this final course on evaluation of educational programs do I see a degree of paradox in this question. How does any country in this increasingly interconnected world we live in, develop autonomously? Yes, it goes without saying that we do what we can, establishing political boarders, creating separate forms of government, and presiding over our own domestic affairs but since about the twentieth century in the United States and even as early as the fourteenth century in Western Europe, these two spheres have influenced so much of North America that it is near impossible to develop ideas independent from that lens. The educational theorist, Chet Bowers refers to this as the complexity of the double-bind. Bowers feels that the lens from which policy makers, and in our case, curriculum writers, operate is already flawed; it is an economically-driven monetized lens of the Western world that disables our ability to see the problems created by that same world (Bowers, 2006, p. 401). As cultures enclose concepts (another Bowers catch phrase) they stake claim to it, trade mark it, so to speak. Any positive or negative associations or understandings we have of those concepts recapitulate themselves generation after generation. So, for better or for worse, the Western world has set our understanding for what is normal, the standard. The lens from which we view what is good or what is bad, what is deemed, effective or ineffective already contains a bias towards the standards set by western democracies.

EDUCATION 830 ASSIGNMENT A

Pagtakhan 2

Inadvertently people who have grown up in Canada or the United States have pre-set criteria in our minds by which we gauge the things that happen in our local communities, countries and the rest of the world. What we may not have been conscious of is how that western, developed world bias is perpetuated in the way we educate our students and evaluate our education programs. THE METANARRATIVE Mostly uncontested, the ideals and values of the United States and Western Europe have played out, in curriculum design. And as the western sphere alters its political agenda in response to foreign or domestic pressures, changing fiscal policies and the desire to remain competitive in foreign markets, education has responded to those ebbs and flows by offering educational programs in line with those mandates. It follows then that the evaluation of those programs is based on the extent to which they are matched with larger political agendas. This section of the paper aims to examine the ideas associated with the United States and other western European democratic nations that have resulted in our view of education, its purpose, subsequent design and evaluation of. This paper attempts to argue that the metanarrative of educational evaluation is that which is fuelled by Western constructs of democracy, free market economy and the promotion of a civil society. Because of this, effective education programs are those which advance and promote the ideals as defined by the nations who subscribe to that same ideology. ESTABLISHING PARTICULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF DEMOCRATIC NATIONS Democracy defined is a particular form of government where citizens have a voice in public policy. It typically connotes the ability to access, influence, and participate. What some may fail to recognize is that the idea of democracy is apparent in most every political ideology ranging from Communism to Conservatism and as such, the democracy of the United States might differ largely from the democracy of China. The variances lie in how each defines active participation in a civil society what people are

EDUCATION 830 ASSIGNMENT A

Pagtakhan 3

actually accessing and for what purpose, what they are influencing and to what extent. For people of western democratic nations, participation is defined by two things: 1) the degree to which one accesses the goods and services of the market and 2) the election of political representatives who enable the citizens involvement to that end. To Hanberger, [c]itizens are viewed as clients, voters as customers, and the democratic citizen is more or less thought of as a consumer. In this notion of civil society, individuals are presumed to act as economic animals maximizing their own interests(Hanberger, 2001, p. 213). A citizens primary purpose in this model is to continue to drive the mechanisms of capitalism and ensure a robust and competitive economy. The purpose may seem narrow but its implications on education have been profound. A WESTERN CAPITALISTIC LENS TO EVALUATE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS The product of this agenda has been to link education more closely to economic interests and principles (Ball, 1998 as cited in Lundahl, 2012, 217). On one level the citizen must be an active participant/consumer while citizens as a whole must be churned out efficiently to serve that function. For that reason the need to evaluate educational programs was born. Programs needed to be assessed according to how effectively they contributed to the notion of a civil society as defined by the capitalist democratic model (Handberger, 2006, p. 222). As such, the language of assessment included words like efficiency, standardization, cost-benefit analysis, and overall effectiveness. Proof of this is found in the work of Madaus and Stufflebaum who map out the history of educational evaluation mechanisms in chapter 1 of their book Evaluation Models: Viewpoints on Educational and Human Services Evaluation (Stufflebeam, Daniel L., 2000). They begin their history lesson with a snapshot of Western developed nations as they underwent an Industrial Revolution in the 1800s. The era embodied laissez-faire capitalism but also bore a humanitarian philosophy which resulted in various educational reform movements (Stufflebaum, 2000, p.4). These were largely government sponsored Commissions of Inquiry into matters surrounding the progress of students in national schools. The chapter uses Ireland as such

EDUCATION 830 ASSIGNMENT A

Pagtakhan 4

an example. Although evaluation of educational programs were largely informal and impressionistic in one particular case it resulted in one schools adoption of a payment by results scheme whereby teachers salaries would be dependent on the results of annual examinations on reading, spelling, writing and arithmetic (Kellaghan & Madaus, 1982; Madaus & Kellaghan, 1992 in Stufflebeam, 200, p. 4). Just as a foreman oversees production in a factory, schools at this time were evaluated by a visiting external inspector who submitted his report on the status and condition of students. These evaluations were funded by federal or state agencies, the obvious stake-holder in capitalist democracies who needed to ensure the quality and uniformity of their product that being the citizen. With governments hard-pressed to be self-sufficient and cost-effective, evaluation of educational programs needed to be quantifiable and comparable. The empiricism in educational evaluation borrowed from the scientific method which essentially meant the students learning or skills acquisition needed to be proven in quantifiable terms. After all, if the purpose of education is to produce employable, consumers then the state needed to ensure that educational programing functioned with this goal in mind.

A THEORY OF EVALUATING OF EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS EMERGES: THE FACTORY MODEL

Because of this, one way educational evaluation has come to be understood is through a factory model. The factory model epitomizes the western developed world, particularly of Britain in the 1800s and most notably, the US in the early 1900s. The two words became synonymous with Henry Fords assembly line that revolutionized the automobile industry allowing for increased industrial output. Basically this translated into profits for the Ford Motor Company. If it worked in industry, the results were bound to be the same in the social services. The message curriculum writers and stakeholders received was that mass production of most anything, including people was possible. This has shaped the general theories we think with when it comes to the evaluation of educational programs. [I]dustrial capitalisms commitment to standardization, uniformity, precision, clarity, quantification and rational

EDUCATION 830 ASSIGNMENT A

Pagtakhan 5

tactics essentially created metaphors in education (Madaus & Kellaghan, inStufflebeam,Daniel L., 2000, p. 20). Kliebard (1972) believes the factory model is apparent in education in a number of ways: The curriculum is the means of production. The student is the raw material to be transformed into a finished product. The teacher is the highly skilled technician. The outcomes of production are carefully plotted in advance according to rigorous design specifications. Certain means prove wasteful and are discarded in favour of more efficient ones. Great care is taken so that raw materials of a particular quality or composition are channelled into the proper product system. No potentially useful characteristic of the raw material is wasted. Prospective employers are the consumers of the finished product. (in Stufflebeam, 2000, p. 21)

With those metaphors in mind, students, the work of teachers, and the programs being implemented had a way of being judged. Stake holders needed only to collect the kind of data that would point to how effective a program or factory was at transforming the raw material into a product the single, uniform product (an issue that will be addressed in part B of the paper). In line with a factory model, that data had to be gathered as efficiently as possible as evaluators too, were no more than upper level management in the same factory system. Program evaluation mechanisms turned to rational methods, or what I call, bean-counting, a collection of marks on standardized tests, statistics on post-secondary entrance rates and the like. Surveys done in a large number of school systems during this period focused on school and/or teachers efficiency using various criteria (for example, expenditures, pupil dropout rate, promotion rates etc.) (Stufflebeam,2000, p. 7) in an attempt to make the entire system more accountable to the managers of the system. The impact of this will be discussed later. But for now, educational evaluation looked to rationalize educational outcomes because rationalization typically uses measurement as a means through which the quality of a product or performance is assessed and represented. Measurement, of course, is one way to describe the world (Eisner, 2001, 368) but educational outcomes cannot be thought of in this limited way. The Age of Efficiency and Testing or Taylorism, after Fredrick Taylor whose work in scientific management led this movement

EDUCATION 830 ASSIGNMENT A

Pagtakhan 6

towards systemization, standardization, efficiency of program evaluation from 1900 to 1930, is how program evaluation would be carried out. As the United States and Europe went through an economic depression in the 1930s program evaluation was necessary to validate or dispute existing educational programs. The manufactured citizen was deemed unsuccessful and incompetent at this time, unable to make significant enough contributions to the GDP. For that reason program evaluation made another shift to an era weve come to know as the Tylerian era. Since support and maintenance of a robust market is of primary importance in western democratic nations and all government attention goes to responding to its fluctuations, educational programing became critical. Education became responsible for diagnosing and remedying the shortcomings of the citizen who was not maximizing their potential in the market. For whatever reason their participation fell short of the expectation; they were either unemployed or underemployed, unable to purchase consumer goods, or were disenfranchised from the system in other ways. Because of this, stakeholders looked to re-evaluate school programs and determine whether their aims promoted the ideals of economic growth and industrialism. This is the primary reason program evaluation became an objectives-based affair; if the objective was clear, the ambiguity of program effectiveness was avoided. For Tyler, an objectives-based program evaluation model would take into account intended outcomes with actual outcomes (Stufflebeam, 2000, p.9). An outcomes-based, industrially-driven program would be deemed a successful from a Tylerian perspective if the student achieved the learning outcomes like employability and economic self-sufficiency. From the post war period to about the last third of the century, these program evaluation methods were not being questioned. I would argue that the democratic governments of west were too preoccupied containing communism in Eastern Europe and Asia to critically assess the existing Tylerian models. Instead governments focused on expanding programs in the name of productivity and social reform. In terms of program evaluation, the emphasis was on doing a better job at stating objectives

EDUCATION 830 ASSIGNMENT A

Pagtakhan 7

more clearly, but not necessarily questioning the industrial objectives or norms set out by curriculum writers. It is only after this period that the field of education began appraising its existing modes of program assessment. The era of the 60s and 70s brought with it an awakening: School districts found that existing tools and strategies employed by their evaluators were largely inappropriate to the task. Available standardized tests had been designed to rank order students on average ability; they were of little use in diagnosing needs and assessing any achievement gains of disadvantaged children whose educational development lagged far behind that of their middle class peers. Instead of measuring outcomes directly related to the school or a particular program, these tests were at best indirect measures of learning, measuring much the same traits as general ability tests. Madaus, Airasian, & Kellaghan in Stufflebeam, 2000, p. 13 The field realized that the techniques of educational evaluation must serve the information needs of the clients of evaluation, address central values issues, meet the requirements of probity and satisfy the needs for veracity (Stufflebeam, 2000, p.15-16). What comes is the realization that educational significance is not so easily measured in quantifiable terms (Judson, personal communication, May 11, 2012). The metaphor of the factory model was problematic and misaligned to what it actually meant to be educated. As such the limitations of this model have resulted in the need for a new way evaluating educational programs.

You might also like

- The Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private SchoolsFrom EverandThe Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private SchoolsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Developing Resilient Youth: Classroom Activities for Social-Emotional CompetenceFrom EverandDeveloping Resilient Youth: Classroom Activities for Social-Emotional CompetenceNo ratings yet

- Pre Publication Version Curriculum DevelopmentDocument33 pagesPre Publication Version Curriculum DevelopmentSoky Escarrilla IrisaryNo ratings yet

- Outcome Based Education: How The Governor's Reform...Document24 pagesOutcome Based Education: How The Governor's Reform...Independence InstituteNo ratings yet

- Commercialization of Teacher Education CritiquedDocument19 pagesCommercialization of Teacher Education CritiquedpilardomingoNo ratings yet

- Annexure-V-Cover Page of Academic TaskDocument16 pagesAnnexure-V-Cover Page of Academic TaskAcademic BunnyNo ratings yet

- Economic Arguments For Gifted EducationDocument5 pagesEconomic Arguments For Gifted EducationMania PappaNo ratings yet

- Group Assignment 1Document56 pagesGroup Assignment 1bojaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument32 pagesUntitledChemutai EzekielNo ratings yet

- Soci1002 Unit 8 - 20200828Document12 pagesSoci1002 Unit 8 - 20200828YvanNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 UcspDocument4 pagesGrade 11 Ucspmarlon anzanoNo ratings yet

- Economics of Education - Analyzing Scarce ResourcesDocument34 pagesEconomics of Education - Analyzing Scarce ResourcesOeNo ratings yet

- Ams Final DraftDocument5 pagesAms Final Draftapi-251225350No ratings yet

- CEE201 Eco. of Edn HS Rout PM SahooDocument55 pagesCEE201 Eco. of Edn HS Rout PM Sahoobaraka2001samuelNo ratings yet

- Workshop 4 Quality Education and The Key Role of Teachers: Background PaperDocument20 pagesWorkshop 4 Quality Education and The Key Role of Teachers: Background Papermustaf mohamedNo ratings yet

- Higher Education and Economic Development Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesHigher Education and Economic Development Literature Reviewc5r3aep1No ratings yet

- Apple 2005Document24 pagesApple 2005Alex MadisNo ratings yet

- Beyond HC1Document17 pagesBeyond HC1GebreyohannesNo ratings yet

- ShakerDocument28 pagesShakerapi-3750208No ratings yet

- PDF WordDocument12 pagesPDF Wordppg.faidildiansyah85No ratings yet

- P A G E Centralisation and Decentralisation in Education and The Role of The State: Implications For Standards and QualityDocument19 pagesP A G E Centralisation and Decentralisation in Education and The Role of The State: Implications For Standards and QualityAkasha KomaleeswaranNo ratings yet

- Civic EducationDocument49 pagesCivic Educationfachripean100% (2)

- 1 - 625 - Autumn 2019Document18 pages1 - 625 - Autumn 2019Shakeel ManshaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Citizenship EducationDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Citizenship Educationixevojrif100% (1)

- Research Paper Education ReformDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Education Reformj0b0lovegim3100% (1)

- Implications of Globalization on Teacher EducationDocument14 pagesImplications of Globalization on Teacher EducationVijaya Ganesh KonarNo ratings yet

- Politics Economics 2010Document20 pagesPolitics Economics 2010Esnerto EmeNo ratings yet

- Chap IDocument63 pagesChap Ivedaste HakizimanaNo ratings yet

- Economic Development 11th Edition Todaro Test BankDocument10 pagesEconomic Development 11th Edition Todaro Test Bankaureliacharmaine7pxw9100% (14)

- Purpose of Studying Comparative EducationDocument7 pagesPurpose of Studying Comparative EducationcifeblogNo ratings yet

- E-Duction and Pro-Duction FINAL-pagenumbers-200512Document11 pagesE-Duction and Pro-Duction FINAL-pagenumbers-200512Stein M. WivestadNo ratings yet

- Implications of Globalization On Educati PDFDocument17 pagesImplications of Globalization On Educati PDFMalitha PeirisNo ratings yet

- Papia Sengupta - Can Ideas Be Deleted Curriculum in PerspDocument6 pagesPapia Sengupta - Can Ideas Be Deleted Curriculum in PerspErnaneNo ratings yet

- Sociological and Political Issues That Affect CurrDocument5 pagesSociological and Political Issues That Affect Curreugene louie ibarraNo ratings yet

- SHS Module 7Document4 pagesSHS Module 7Maecy S. PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- Essay: A Response To Shcweisfurth Essay On ReformDocument20 pagesEssay: A Response To Shcweisfurth Essay On ReformsorenzaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics in Social Studies EducationDocument7 pagesDissertation Topics in Social Studies EducationHelpWithPapersCanada100% (1)

- 6466 1Document18 pages6466 1Sani Khan100% (1)

- Introduction - To The End of Part 1 - Page 3Document2 pagesIntroduction - To The End of Part 1 - Page 3Pradeep WeerathungaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum debate important for social justiceDocument20 pagesCurriculum debate important for social justiceJ Khedrup R TaskerNo ratings yet

- 2012 Robertson Verger Governing EducationDocument31 pages2012 Robertson Verger Governing Educationasdf789456123No ratings yet

- Canadian Education Forum Report Explores Shifting Conceptions of EducationDocument3 pagesCanadian Education Forum Report Explores Shifting Conceptions of EducationsotyakamNo ratings yet

- Writing The Show Me Standards Teacher Professionalism and Political Control in U S State Curriculum PolicyDocument31 pagesWriting The Show Me Standards Teacher Professionalism and Political Control in U S State Curriculum PolicyMuse MusikaNo ratings yet

- Navia - Sequence No. 25 - Human Capital Theory Impact To Education and LearningDocument22 pagesNavia - Sequence No. 25 - Human Capital Theory Impact To Education and LearningMa Sharlyn Ariego NaviaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Privatization of EducationDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Privatization of Educationegyey4bp100% (1)

- OnesizefitsalleducationDocument13 pagesOnesizefitsalleducationapi-309799896No ratings yet

- Comparative Educational System E-LearningDocument217 pagesComparative Educational System E-LearningThea Venice Anne De Mesa100% (1)

- Education and Its LegitimacyDocument4 pagesEducation and Its LegitimacySheila G. Dolipas100% (6)

- The Learning Edge in DevelopmentDocument96 pagesThe Learning Edge in DevelopmentSafwan MahadiNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Curriculum DesignDocument28 pagesFactors Influencing Curriculum Designanna39No ratings yet

- EDUC 203 Curriculum Development S.Y. 2020 - 2021Document48 pagesEDUC 203 Curriculum Development S.Y. 2020 - 2021Xyra Kristi Palac TorrevillasNo ratings yet

- Bab 4 KewarganegaraanDocument19 pagesBab 4 KewarganegaraanLitaNursabaNo ratings yet

- Education As Consumption and InvestmentDocument7 pagesEducation As Consumption and Investmentmichaelkmaina99No ratings yet

- Thesis On Elementary Education in IndiaDocument8 pagesThesis On Elementary Education in Indiafjfcww51100% (2)

- Teaching and Globalization: How Standardization and Competition Affect EducationDocument19 pagesTeaching and Globalization: How Standardization and Competition Affect EducationAvinash BoodhooNo ratings yet

- Block 2 .Eco of Edu 4-6 NotesDocument24 pagesBlock 2 .Eco of Edu 4-6 Notesus nNo ratings yet

- A Review On The Book EntitledDocument3 pagesA Review On The Book EntitledKristine Lovele NavarreteNo ratings yet

- From Globalist To Cosmopolitan Learning On The RefDocument24 pagesFrom Globalist To Cosmopolitan Learning On The RefEldar ĆerimNo ratings yet

- EMP Lesson 1-9Document34 pagesEMP Lesson 1-9jenipherwangeciNo ratings yet

- Reimagining Schools and School Systems: Success for All Students in All SettingsFrom EverandReimagining Schools and School Systems: Success for All Students in All SettingsNo ratings yet

- Timeline 1955-2005Document1 pageTimeline 1955-2005api-42688552No ratings yet

- Guiding Questions For July ReadingsDocument17 pagesGuiding Questions For July Readingsapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Charter Rights FreedomsDocument6 pagesCharter Rights Freedomsapi-42688552No ratings yet

- World MapDocument1 pageWorld Mapapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Kipp (Lindsey & Lauren'S Presentation) : Lunch BreakDocument5 pagesKipp (Lindsey & Lauren'S Presentation) : Lunch Breakapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Teacher Generated Plot DiagramDocument1 pageTeacher Generated Plot Diagramapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Essay Scoring CriteriaDocument1 pageEssay Scoring Criteriaapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Timeline 1900-1950Document1 pageTimeline 1900-1950api-42688552No ratings yet

- Prime Ministers of CanadaDocument2 pagesPrime Ministers of Canadaapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Part e Draft 4Document11 pagesPart e Draft 4api-42688552No ratings yet

- Command Words For Socials EssaysDocument1 pageCommand Words For Socials Essaysapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Guiding Questions For July ReadingsDocument12 pagesGuiding Questions For July Readingsapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Description of Essay Organizers 2015Document2 pagesDescription of Essay Organizers 2015api-42688552No ratings yet

- Story Structure Report Card To Parent To 1 PGDocument2 pagesStory Structure Report Card To Parent To 1 PGapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Plot Diagram of GR 10 Socials Unit Draft 2Document1 pagePlot Diagram of GR 10 Socials Unit Draft 2api-42688552No ratings yet

- Part D Draft 5Document10 pagesPart D Draft 5api-42688552No ratings yet

- Geometry Ie UnitDocument6 pagesGeometry Ie Unitapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Karo and EmmaDocument22 pagesKaro and Emmaapi-42688552No ratings yet

- NW Rebellion Ie UnitDocument9 pagesNW Rebellion Ie Unitapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Colour - Ie UnitDocument4 pagesColour - Ie Unitapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Sage Caterpillars Draft 2Document5 pagesSage Caterpillars Draft 2api-42688552No ratings yet

- Sandra and LindaDocument20 pagesSandra and Lindaapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Evaluation and DignityDocument5 pagesEvaluation and Dignityapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Presentation ScheduleDocument3 pagesPresentation Scheduleapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Dimension Chart Eisner Draft 2Document9 pagesDimension Chart Eisner Draft 2api-42688552No ratings yet

- Part C Nina PagtakhanDocument2 pagesPart C Nina Pagtakhanapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Part B Nina PagtakhanDocument3 pagesPart B Nina Pagtakhanapi-42688552No ratings yet

- June 23 Independent StudyDocument4 pagesJune 23 Independent Studyapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Guiding Questions For June 8 and 9Document9 pagesGuiding Questions For June 8 and 9api-42688552No ratings yet

- 21st Century Literature Q1 Module5 RepTextsVisayas 1Document29 pages21st Century Literature Q1 Module5 RepTextsVisayas 1Diana Rose Dawa CordovaNo ratings yet

- COT - DLP - SCIENCE - 6 - EARTH - S - ROTATION - BY - MASTER - TEACHER - EVA - M. - CORVERA - Doc - F (1) (AutoRecovered)Document13 pagesCOT - DLP - SCIENCE - 6 - EARTH - S - ROTATION - BY - MASTER - TEACHER - EVA - M. - CORVERA - Doc - F (1) (AutoRecovered)gener r. rodelasNo ratings yet

- Seal of BiliteracyDocument1 pageSeal of BiliteracyrogelioNo ratings yet

- Adult Learning Theories in Medical EducationDocument7 pagesAdult Learning Theories in Medical EducationPamela Tamara Fernández EscobarNo ratings yet

- Summative and Formative Assessments: Group C Laura Nemer, Yancy Munoz, Davisha Pratt, Gina PetrozelliDocument30 pagesSummative and Formative Assessments: Group C Laura Nemer, Yancy Munoz, Davisha Pratt, Gina PetrozelliSylvaen WswNo ratings yet

- Brainstorming For Research TopicsDocument18 pagesBrainstorming For Research TopicsMa. Aiza SantosNo ratings yet

- Masiullah New CV Update...Document4 pagesMasiullah New CV Update...Jahanzeb KhanNo ratings yet

- Best Online Coaching Institutes For IIT JEE Main and AdvancedDocument3 pagesBest Online Coaching Institutes For IIT JEE Main and AdvancedArun GargNo ratings yet

- 1 - Action ResearchDocument20 pages1 - Action Researchapi-256724187100% (1)

- .Sustainable Tourism Course OutlineDocument8 pages.Sustainable Tourism Course OutlineAngelica LozadaNo ratings yet

- Reading and Writing Numbers Up to 1000Document3 pagesReading and Writing Numbers Up to 1000Hann alvarezNo ratings yet

- Popular English Grammar Books: Want To ReadDocument2 pagesPopular English Grammar Books: Want To ReadkatnavNo ratings yet

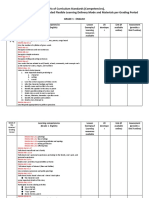

- Matrix of Curriculum Standards (Competencies), With Corresponding Recommended Flexible Learning Delivery Mode and Materials Per Grading PeriodDocument3 pagesMatrix of Curriculum Standards (Competencies), With Corresponding Recommended Flexible Learning Delivery Mode and Materials Per Grading PeriodEvan Maagad LutchaNo ratings yet

- Final Project SyllabusDocument4 pagesFinal Project Syllabusapi-709206191No ratings yet

- And Mathematics, It Is An Multi and Interdisciplinary Applied ApproachDocument4 pagesAnd Mathematics, It Is An Multi and Interdisciplinary Applied ApproachVeeru PatelNo ratings yet

- Dissertation FrontDocument4 pagesDissertation FrontDeepika SahooNo ratings yet

- Horse Riding LessonsDocument11 pagesHorse Riding LessonsDalsonparkNo ratings yet

- Canada Nurse Registration ProcessesDocument3 pagesCanada Nurse Registration ProcessesNimraj PatelNo ratings yet

- DLP Reading Amp Writing Feb 17 Co1Document2 pagesDLP Reading Amp Writing Feb 17 Co1Peache Nadenne LopezNo ratings yet

- Personal Value and Job Satisfaction of Private B.Ed. College TeachersDocument8 pagesPersonal Value and Job Satisfaction of Private B.Ed. College TeachersEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Gen201 v11 New wk3 College Communication WorksheetDocument2 pagesGen201 v11 New wk3 College Communication WorksheetTelisia DewberryNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Problem-Based Learning: A User GuideDocument34 pagesAn Introduction To Problem-Based Learning: A User GuideChairun NajahNo ratings yet

- 0610 w04 Ms 1Document4 pages0610 w04 Ms 1Hubbak Khan100% (4)

- Maths PedagogyDocument30 pagesMaths PedagogyNafia Akhter100% (1)

- A Whole New Engineer Sample 9 2014aDocument15 pagesA Whole New Engineer Sample 9 2014aKyeyune AbrahamNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument3 pagesDocumentImee C. CardonaNo ratings yet

- Sim On Food PackagingDocument15 pagesSim On Food PackagingRaymund June Tinga-Enderes Alemania83% (18)

- PEH1 - Week 2 (Introduction To Physical Education)Document5 pagesPEH1 - Week 2 (Introduction To Physical Education)Japan LoverNo ratings yet

- Table of Specifications: San Sebastian Cathedral School of Tarlac, IncDocument1 pageTable of Specifications: San Sebastian Cathedral School of Tarlac, IncGerald VasquezNo ratings yet

- What I Have Learned: Learning Task 5Document1 pageWhat I Have Learned: Learning Task 5Janna Gunio100% (2)