Professional Documents

Culture Documents

China 101

Uploaded by

Carter LiangOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

China 101

Uploaded by

Carter LiangCopyright:

Available Formats

Emerging Markets Equity Research

31 May 2011

China 2020: 130 million swing

How demographics change the economy

The number of graduates in China has increased by 74 million in past decade (2010 Census). The tertiary enrolment ratio is now 35%. This combined with a 2% decline in the working age population leads to a 91 million fall in non-graduates in the workforce; it grew by 28 million in 2000-2010. We believe that this is the most important driver of reduce fixed asset investment. It reverses the commonly held belief that China must have growth above 8% to generate sufficient jobs. Continuing the current investment-driven model will be inflationary. Chinas official GDP growth target and inflation rate for this decade are 7% and 4%, respectively. Considering a 10.5% GDP CAGR in 2000-2010 with just 2% inflation, this lower target appears conservative. To achieve the 7% target China requires circa10% labor productivity. It is investment in human capital that makes this high level of productivity possible, as higher-paying service sector jobs replace lower-paid construction and manufacturing jobs. The challenge is creating jobs for graduates. If we assume a return to the consumption/investment ratio in 2000 and 7% GDP growth, the consumption CAGR accelerates from 8.5% to 8.9%. Fixed investment CAGR falls from 12.7% to 4.8% (see page 10). Commodity bulls take note. The 12th Five-Year Plan aims to rebalance. But it is Chinas 1979 one-child policy that is driving economic change today.

EM 101

Emerging Markets Equity Strategy Adrian Mowat

AC

(852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited

Ben Laidler

(1-212) 622-5252 ben.m.laidler@jpmorgan.com J.P. Morgan Securities LLC

David Aserkoff, CFA

(44-20) 7325-1775 david.aserkoff@jpmorgan.com J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd.

Rajiv Batra

(91-22) 6157-3568 rajiv.j.batra@jpmorgan.com J.P. Morgan India Private Limited

Faheem S Desai

(91-22) 6157-3329 faheem.s.desai@jpmorgan.com J.P. Morgan India Private Limited

Ravi Saraogi

(91-22) 6157-3305 ravi.saraogi@jpmorgan.com J.P. Morgan India Private Limited

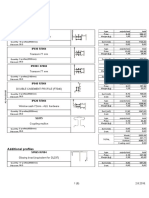

Figure 1: Demographics should reverse this trend

800% 700% 600% 500% 400% 300% 200% 100% 0% 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

Source: CEIC. Note: Household income lagging profits and GDP growth

748%

GDP Government Profits Income

Figure 2: China needs jobs for graduates, not in pouring concrete or manufacturing: Change in the non-graduate available workforce 15-39 years old

%oya, Millions

3% 2% 1% 0% -1% -2% -3% -4% -5% -6% 600 500 400 300 200 100 0

512% 343% 258%

%oya

Number

Source: PRC NBS, Ministry of Education PRC, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculation

See page 28 for analyst certification and important disclosures, including non-US analyst disclosures.

J.P. Morgan does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. As a result, investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision.

1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 2023 2026 2029 2032 2035 2038 2041 2044 2047

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

EM 101 Series

EM 101 key briefing notes for emerging market equity investors.

Table of Contents

Figure 1: Demographics should reverse this trend.......................................................1 Figure 2: China needs jobs for graduates, not in pouring concrete or manufacturing: Change in the non-graduate available workforce 15-39 years old ...............................1 Figure 4: Change in the non-graduate available workforce 15-39 years old................3 Figure 5: And reverse this trend...................................................................................3 Figure 6: Real GDP growth (2000=100)......................................................................4 Figure 7: Contribution to Chinas real GDP growth ....................................................4 Figure 8: Growth in per capita GDP & average national wages (%) ...........................4 Figure 9: From consumption to investment .................................................................5 Figure 10: Household income lagging profits and GDP growth..................................5 Figure 11: More 19 years old in Tertiary Education - Less for construction, manufacturing and agriculture .....................................................................................9 Figure 12: Change and absolute number of 19 year old non-graduates .......................9 Figure 13: Change in the non-graduate available workforce 15-39 years old..............9 Figure 14: Tertiary enrollment ratio as a percentage of 19 years old...........................9 Figure 15: China labor productivity growth (%)........................................................10 Figure 16: China export price index (%oya, nsa).......................................................10 Figure 17: China FAI breakdown ..............................................................................11 Figure 18: China ICOR..............................................................................................12 Figure 19: China export prices and US import prices from China.............................13 Figure 20: Export price trends - China, Korea and Taiwan .......................................13 Figure 21: Manufacturing wages relative to industry output .....................................13 Figure 22: Share of US import market.......................................................................14 Figure 23: Industrial enterprise profit margin ............................................................14 Figure 24: China exports by region............................................................................14 Figure 25: Lessons from other countries - Real GDP growth (5-year centered moving average %) vs. adjusted per capita GDP (US$) .........................................................16 Figure 26: Real GDP growth %oya (5-year centered moving average) over time.....17 Figure 27: Relative growth and wealth of provinces in China...................................18 Figure 28: Real GDP growth vs. Average CPI in the previous decades ....................19 Figure 29: Intensity of cement use; per-capita consumption of cement (tonnes) vs. adjusted per-capita nominal GDP ..............................................................................20 Figure 30: Intensity of steel use; per-capita consumption of steel (lbs) vs. adjusted per-capita nominal GDP ............................................................................................21 Figure 31: Per-capita consumption of oil (barrels per day per 1000 population) vs. adjusted per-capita nominal GDP ..............................................................................22 Figure 32: Total energy consumption in China higher than in the US but low at a percapita level; per-capita consumption of primary energy (tonnes of oil equivalent) vs. per adjusted capita nominal GDP...............................................................................23 Figure 33: Mobile subscription per 100 people vs. adjusted per capita nominal GDP ...................................................................................................................................24 Figure 34: China is already the worlds largest car marketbut still low per 1000 people; passenger cars per 1000 people vs. adjusted per capita nominal GDP..........25 Figure 35: Share of global nominal GDP (%) Chinas share is 10% in 2010 and forecast to be 17% in 2020.........................................................................................26

For more on this subject from J.P. Morgans economics team please see: Chinas consumption uptrend and role of labor market, 30 July 2010, Grace Ng et al Chinas export sector copes with rising wages, 4 March 2011, Grace Ng et al (See page 13) Riding on the coattails of Chinas rising labor cost, 25 March 2011, Sin Beng Ong et al

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Demographics driving change

Chinas official growth target and inflation rate for this decade are 7% and 4% respectively. Considering its historic double-digit growth rate with just 2% inflation, this lower target appears conservative. But China faces demographic and structural challenges that investors need to consider. The catalyst for writing this paper was the following statement in the Nation Bureau of Statistics press release on the November 2010 Census: Compared with the 2000 population census, following changes took place in the number of people with various educational attainments of every 100,000 people: number of people with university education increased from 3611 to 8930;. Chinas investment in physical infrastructure is legendary. On page 11 we review the impact of cheap money and an increase in the capital to output ratio. We believe investors are underestimating the investment in human capital. This provides China with the ability to maintain high growth through shifting labor from manufacturing, construction and agriculture to services. But it cannot continue the investment driven growth model of the 2000s. China leaders acknowledge this in the 12th Five Year Plan with its focus on rebalancing the economy from investment to consumption plus rebalancing of income distribution from profits to household income. Our view is optimistic. The investment in both physical and critically human capital permits high productivity that is needed to drive growth with a declining working age population. The winners are: 1. Consumers and consumer companies 2. Automation 3. Service sector growth 4. The environment 5. Countries with better demographics The losers are 1. Intensity of commodity demand 2. Low value added labor intensive industries

Table 1: Calculation of the change in the number of graduates in China 2000 to 2010 based on Census data

Year 2000 2010 Change Ratio 3.61% 8.93% 5.32% Population 1,265,824,852 1,339,724,852 73,900,000 Graduates 45,708,935 119,637,429 73,928,494

Figure 3: More 19-year-olds in Tertiary Education - Less for construction, manufacturing and agriculture

Millions

30.0 25.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 0.0 Under-graduates Non-graduates

Source: PRC NBS, Ministry of Education PRC, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculation

Figure 4: Change in the non-graduate available workforce 15-39 years old

%oya, Millions

3% 2% 1% 0% -1% -2% -3% -4% -5% -6% %oya Number 600 500 400 300 200 100 0

Source: PRC NBS, Ministry of Education PRC, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculation

Figure 5: And reverse this trend

% of nominal GDP

65 60 55 50 45 40 35 30 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Source: IMF, Datastream, J.P. Morgan calculation

Source: PRC National Bureau of Statistics; November 2010 Census

1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 2023 2026 2029 2032 2035 2038 2041 2044 2047

Fixed investment Private consumption Total consumption

3

1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 2023 2026 2029 2032 2035 2038 2041 2044 2047

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

2000s: High growth with low inflation

The economy: 2000 to 2010 Real GDP CAGR of 10.5% Nominal GDP CAGR of 15% 2010 nominal GDP = Rmb40trillion or US$5880 billion. This is 10% of global GDP. Per capita GDP CAGR of 14.3% CPI CAGR of 2%; significantly lower than the CPI CAGR 1990 to 2000 of 7%. Rmb/US$ CAGR of 2% from 8.277 to 6.6. But the exchange rate was fixed until 21 July 2005; the CAGR from this point to end 2010 was 4%. Average national wage CAGR of 14.6%. There was a sharp acceleration in 2007-08 when the average growth was 18%. Minimum wages are growing faster than the national average wage. The minimum wage CAGR 17.8% from 2005-09. In 2010, minimum wages were increased by a substantial 23% to compensate for the lack of increment during the 2009 slowdown. Growth was led by fixed investment while consumption lagged: Fixed investment CAGR of 12.7% Domestic consumption CAGR of 8.5% Net external demand CAGR of 11.4%

Figure 6: Real GDP growth (2000=100)

500 400 300 200 100 0 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 Real GDP Consumption Inv estment External demand

Source: J.P. Morgan economics.

Figure 7: Contribution to Chinas real GDP growth

15 10 5 0 -5 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 Real consumption Real investment Real net external demand

Source: J.P. Morgan economics.

Figure 8: Growth in per capita GDP & average national wages (%)

22 19 Per capita GDP Wages

There are no other countries that have achieved the same combination of low inflation and high growth that China had in the 2000s. For the past 30 years the country has developed with an assumption of unlimited labor, notably underemployed agricultural workers.

16 13 10 7 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10

Source: CEIC, IMF.

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Investment-led growth in the 2000s Chinas economic development is a souped-up version of the Asian investment led growth model. The contribution of fixed investment to GDP growth surpassed the contribution from real consumption in 2003 (see Figure 7). In 2009 fixed investment contributed 8.6% of China's 9.1% real GDP growth, helping offset the sharp contraction in external demand. In the past decade, as a percentage of nominal GDP fixed investment increased from 34% to 46%. Consumption declined from 62% to 48%; private consumption fell from 46% to 35% (see Figure 9). Financing an investment growth model requires a wealth transfer from households to profits. The subsidy is achieved via low wages, low return on savings and an undervalued currency. The impact of this policy is clear in Figure 10; industrial profits grew at 25% CAGR from 2000-09, more than double the pace of household income growth of 11%. The 12th Five-Year Plan acknowledged the inequality of growth with an aim to balance revenue distribution among enterprises, individuals, central governments and local authorities. The intensity of commodity use increased sharply. Commodity consumption grew in the high teens in the last decade (see Table 2). In 2010, China accounted for over half of the worlds iron ore demand. China cement consumption is remarkable (see Figure 29). China's per capita cement consumption was 1.34tonnes in 2010. Korea in 1997 did reach the same level of per capita cement consumption that China achieved in 2010. But Korean per capita GDP in 1997 (in today's dollars) was four times Chinas current per capita GDP. In 1998 Korea had a current account crisis. Note the trend in Taiwans per capita cement demand. Taiwan property prices peaked in 1994, a year after the peak in cement demand. J.P. Morgans equity strategy team is less optimistic about China commodity demand than the consensus (see page 12). There are numerous reasons discussed below that require a move away from an investment-led growth model.

Figure 9: From consumption to investment

% of nominal GDP

65 60 55 50 45 40 35 30 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Source: J.P. Morgan economics, IMF

Fixed investment Private consumption Total consumption

Figure 10: Household income lagging profits and GDP growth

800% 700% 600% 500% 400% 300% 200% 100% 0% 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

Source: CEIC.

748%

GDP Government Profits Income

512% 343% 258%

Table 2: China's dominant share of global commodity demand and CAGR 2000-10

China share of global demand (%) Aluminum Nickel Copper Iron ore 13 12 20 15 15 21 16 16 23 18 11 19 26 20 13 21 30 22 15 23 36 26 18 23 40 32 23 26 43 33 23 28 47 39 32 37 60 41 33 37 57 17.5 20.5* 14.6 19.9

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 CAGR (2000-10)

Source: J.P. Morgan commodities research and Brook Hunt historic. * Nickel demand CAGR is from 2003-10.

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Demographic transition China published the results of it 2010 census in April. On 1 November 2010 the total population was 1,339,724,852. The growth from 2000 was just 73.9 million, or a 0.57% CAGR. The growth rate halved compared to the 1990s, which had a CAGR 1.07%. The decline in the fertility rate partly explains the reduction from 3.44 to 3.1 people per household. The number of households was 401.5million. The growth in total population is forecast to slow to 0.3% CAGR in 2010-20. In the 2000s the working age population increased by 12% a CAGR of 1.2%. This is the decade when China's working age population will start to decline. The working age population comprised 69% of the total population in 2010. It grew 12% from 2000 to 2010, a CAGR of 1.2%. According to the US Census, the working age population is expected to contract by 1.8%, or a -0.2% CAGR, this decade (see Table 3). The population under the age of 14 declined by 6.3% to 16.6%. The population is aging rapidly, with 13.3% over 60 years, an increase of 2.9% compared to 2000. The population is ethnically homogeneous, with 91% Han Chinese. The urban and rural split is now 50:50. The urban population is 665.6 million and rural 674.2 million. In 2000 the urban population was 36%. This is low even compared to other emerging markets (see Table 5). Chinas urbanization rate was a 3.8% CAGR in the last decade. This was the fastest rate of urbanization across EM and DM (see Table 4). Each year China added 21 million to its urban population. It is assumed that the urbanization rate will slow to 2.1% during this decade. The population is shifting, with an 81% increase in the population living in a different location than their town of registration. This growth rate may be exaggerated by a new methodology for counting unregistered migrant labor in the 2010 census. The shift is to the wealthy Eastern region. The peak in Chinas working age population is well known. It is the rate of urbanisation that is debatable. In the past decade it exceeded estimates. There is no clear relationship between per-capita GDP and the urbanization rate, and there is a large spread of urbanization rates across developed and emerging economies.

Table 3: Chinas working age population

(millions) 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 Population Working age 724 819 921 905 830 Total 1148 1264 1340 1385 1391 Working age popn % of total popn 63 65 69 65 60 Growth in working age popn (%) 13.2 12.4 -1.8 -8.2

Source: US Census.

Table 4: Urbanization rate in the last decade and current (CAGR)

% EM China Malaysia India Philippines Morocco Turkey Egypt South Africa Colombia Israel Brazil Peru Indonesia Thailand Mexico Chile Argentina Korea Hungary Czech Republic Poland Russia DM Singapore France US Australia Italy UK Hong Kong SAR Japan Germany 2000-2010 3.8 3.3 2.3 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 1.9 1.8 1.8 1.8 1.8 1.8 1.5 1.4 1.2 0.8 0.3 0.1 -0.2 -0.5 1.9 1.6 1.4 1.4 0.7 0.6 0.6 0.3 0.1 2010-2020 2.1 2.2 2.4 2.3 2.1 1.6 2.1 1.2 1.6 1.4 1.0 1.5 1.7 1.8 1.1 1.1 1.0 0.5 0.3 0.3 0.0 -0.2 0.8 0.9 1.2 1.1 0.4 0.7 0.9 0.1 0.0

Source: United Nations, World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision Population Database.

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Demographics drive rebalancing

Chinas official growth target and inflation rate for this decade is 7% and 4% respectively. This is a reasonable base case. In this section we review the assumptions that we believe investors should watch. Simple model Theoretical potential GDP growth = the change in the hours worked + productivity adjustment factor. This is a gross simplification of the dynamics of the worlds second largest economy. The key demographic assumptions are: 1. The CAGR of the working age population was 1.2% in the last decade. The US Census forecast minus 0.2% CAGR in the working age population this decade. 2. In the 2000s the urbanization CAGR was 3.8%; the highest globally. The UN forecast urbanization CAGR 2.1% this decade. 3. The CAGR in the urban working age population is forecast to decelerate from 4.5% to 1.2%. In 2008, China had the highest labor productivity globally (measured by GDP per person engaged). Labor productivity growth was a 10.5% CAGR in 2000-08 (as per the International Labor Organization). The range is wide with the maximum at 14% and the minimum at 8%. Urbanization, growth and productivity The high rate of urbanization in the last decade contributed to higher labor productivity as the population migrated from lower return agricultural jobs to higher income manufacturing jobs. We solve for the adjustment factor using both the 2000s growth in working age population and urban working age population. In Table 6 and Table 7 we calculate the 2010 to 2020 potential GDP using the growth in working age and urban working age population. The challenge for China is maintaining a high level of productivity growth. The arguments in favor of maintaining high productivity growth are: 1. Investment in human capital: In the past decade the ratio of the population with a university degree increased from 3.6% to 8.9%. That is an increase of 74 million graduates, more than the population of Thailand. A third of 19-year-olds (circa 21 million) are undergraduates. If China can generate service sector jobs, the migration from manufacturing to service will boost productivity.

Table 5: Urban population as a percentage of the total population

% EM Argentina Israel Chile Brazil Republic of Korea Mexico Peru Colombia Czech Republic Russian Federation Malaysia Turkey Hungary South Africa Poland Morocco China Philippines Indonesia Egypt Thailand India DM Hong Kong SAR Singapore Australia France United States of America United Kingdom Germany Italy Japan 1990 87 90 83 74 74 71 69 68 75 73 50 59 66 52 61 48 26 49 31 43 29 26 100 100 85 74 75 78 73 67 63 2000 90 91 86 81 80 75 73 72 74 73 62 65 65 57 62 53 36 48 42 43 31 28 100 100 87 77 79 79 73 67 65 2010 92 92 89 87 83 78 77 75 74 73 72 70 68 62 61 58 50 49 44 43 34 30 100 100 89 85 82 80 74 68 67 2020 94 92 91 90 86 81 80 78 75 75 78 74 72 67 62 64 55 53 48 46 39 34 100 100 91 90 85 81 76 71 69

Source: United Nations, World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision Population Database. Table sorted by urban population % of total in 2010.

Table 6: Sensitivity of potential GDP calculation to productivity using the growth in working age population

Parameters Working age pop growth Productivity growth Adjustment factor Potential GDP

Source: J.P. Morgan calculation

#1 -0.2 6 1.2 4.6

#2 -0.2 8 1.2 6.6

#3 -0.2 10 1.2 8.6

#4 -0.2 12 1.2 10.6

Table 7: Sensitivity of potential GDP calculation to productivity using the growth in urban working age population

Parameters Urban working age pop growth Productivity growth Adjustment factor Potential GDP

Source: J.P. Morgan calculation

#1 1.2 6 4.5 2.7

#2 1.2 8 4.5 4.7

#3 1.2 10 4.5 6.7

#4 1.2 12 4.5 8.7

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

2. Low cost of capital: The 12-month best lending rate is 6.31%. A real rate of 2.3% assuming the new CPI target of 4%. The discount to nominal GDP growth target is 3.7%. The low cost of capital relative to growth lowers the hurdle rate for productive capex. 3. Economies of scale and clustering: The large scale of manufacturing facilities in China permits the investment in R&D for customized automation. 4. Infrastructure: Huge investment in infrastructure increases logistic efficiency. Shorter delivery times and superior inventory management allow for premium pricing. The non-graduate labor shortage A key data point from the November 2010 census was: Compared with the 2000 population census, following changes took place in the number of people with various educational attainments of every 100,000 people: number of people with university education increased from 3611 to 8930; number of people with senior secondary education increased from 11146 to 14032; the number of people with junior secondary education increased from 33961 to 38788; and the number of people with a primary education decreased from 35701 to 26779. (Source: National Bureau of Statistics press release on Major Figures of the 2010 National Population Census). An increase from 3.6% to 8.9% of the population with a university degree means that the number of graduates in China increased by 73.9 million in the past decade. This figure is 116% higher than the Ministry of Education Data in CEIC. Based on the Ministry of Education website the discrepancy may be partly explained by the 1.9 million graduates in adult higher education institutes and the 1 million web-based graduates (see Table 11, http://www.moe.edu.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/mo e/s4969/201012/113484.html). Based on Ministry of Education press release, 180,000 students went abroad to study. Note that new entrants in 2010 were 8.4 million.

Table 8: Calculation of the change in the number of graduates in China 2000 to 2010 based on Census data

Year 2000 2010 Change Ratio 3.61% 8.93% 5.32% Population 1,265,824,852 1,339,724,852 73,900,000 Graduates 45,708,935 119,637,429 73,928,494

swing of 130 million will add to wage inflation in manufacturing and construction. We believe that this is the most important driver of the need for China to reduce its fixed asset investment. It reverses the commonly held belief that China must have growth above 8% to generate sufficient jobs.

Table 9: Key population statistics

Size (million) Population Working age population Over 60 population Over 60 population (%) Urban population (%) Urban population Household size Urban households 1990 1,148 724 63 5% 26% 299 3.7 81 2000 1,264 819 86 7% 36% 455 3.4 132 2010 1,330 921 115 9% 50% 665 3.1 215 2020 1,385 905 172 12% 62% 851 3.1 275 2030 1,391 830 239 17% 68% 950 3.1 306

Source: NBS China, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculations

Table 10: Annual growth key population statistics

CAGR (%) Population Working age population Over 60 population Urban population Household size Urban households 2000 1.0% 1.2% 3.2% 4.3% -0.7% 5.1% 2010 0.5% 1.2% 2.9% 3.9% -1.0% 5.0% 2020 0.4% -0.2% 4.1% 2.5% 0.0% 2.5% 2030 0.1% -0.9% 3.3% 1.1% 0.0% 1.1% 2040 -0.2% -0.8% 3.2% 0.8% 0.0% 0.8%

Source: NBS China, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculations

Table 11: Number of graduates in China

0000s Graduates Higher Education Postgraduates Doctor's Degrees Master's Degrees Undergraduates in Regular HEIs Normal Courses Short-cycle Courses Undergraduates in Adult HEIs Normal Courses Short-cycle Courses Web-based Undergraduates Normal Courses Short-cycle Courses Total Undergraduate 371 49 323 5,311 2,455 2,856 1,944 865 1,078 984 406 578 8,238 New Entrants 511 62 449 6,395 3,261 3,134 2,015 816 1,199 1,626 551 1,074 10,035 Total Enrolment 1,405 246 1,159 21,447 11,799 9,648 5,414 2,257 3,157 4,173 1,573 2,600 31,033

Source: Ministry of Education of the PRC (29 December 2010)

Source: PRC National Bureau of Statistics; November 2010 Census

We forecast a 90 million decline in the non-graduate working-age population. In the 2000s the non-graduate working age population expanded by 30 million. This

8

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

130 million decline in manual workforce We use a number of data sources and assumptions to calculate the change in the non-graduate workforce. As noted above the November 2010 Census highlighted a 74 million increase in graduates in China. This is higher than the CEIC data from the Ministry of Education. Combining both regular and adult data 8.4 million new graduates entered university in 2010. The enrolment-tograduate ratio is 3.5 (calculated from Ministry of Education website). We assume that the number of new entrants remains at 8.4 million through to 2049; this is conservative. The available non-graduate workforce aged 15-39 is calculated excluding cumulative graduate (of that age group) and those enrolled in university. The Chinese manufacturing sector has historically used young migrant labor. The combination of a shrinking pool of 15-39 years old and the upgrading of their skill set argues for a sharp decline in the workforce willing to work in manufacturing and construction. The challenge for China is generating jobs for the eight million graduates entering the work force each year. Graduate unemployment is already a source of concern. It is arguably harder for government policy to drive service sector employment than manual and semiskilled through stimulus programs.

Figure 12: Change and absolute number of 19-year-old nongraduates

%oya, Millions

6.0% 4.0% 2.0% 0.0% -2.0% -4.0% -6.0% -8.0% -10.0% -12.0% %oya Non-graduates 30 25 20 15 10 5 0

Source: PRC NBS, Ministry of Education PRC, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculation

Figure 13: Change in the non-graduate available workforce 15-39 years old

%oya, Millions

3% 2% 1% 0% -1% -2% -3% -4% -5% -6% %oya Number 600 500 400 300 200 100 0

Source: PRC NBS, Ministry of Education PRC, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculation

Figure 11: More 19 years old in Tertiary Education - Less for construction, manufacturing and agriculture

Millions

30.0 25.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 0.0 Under-graduates Non-graduates

Figure 14: Tertiary enrolment ratio as a percentage of 19-yearolds

80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0%

1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 2023 2026 2029 2032 2035 2038 2041 2044 2047

Source: PRC NBS, Ministry of Education PRC, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculation

Source: PRC NBS, Ministry of Education PRC, US Census, J.P. Morgan calculation

1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 2023 2026 2029 2032 2035 2038 2041 2044 2047

9

1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 2023 2026 2029 2032 2035 2038 2041 2044 2047

1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017 2020 2023 2026 2029 2032 2035 2038 2041 2044 2047

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Net external demand a drag on growth? FT Confidential (7 April 2011) forecast 20-30% wage inflation for the 166 million migrant workers. In the same report Hong Kong Footwear Makers Association in Dongguan reported a 5% drop in orders post a margin protecting 15% increase in prices. Textile and footwear orders are shifting to Bangladesh, India and Vietnam. Minimum wages in India and Vietnam are US$96 and US$62 per month compares to China's lowest minimum wage in the Western provinces of US$130 (RMB850). The minimum wage in Shenzhen, Guangdong is US$200 (Rmb1320). Note that China already has a significant share in high value added exports including electronics and machinery. It is reasonable to assume that Chinas trade surplus narrows as it loses market share in low-value-added industry. This is potentially a win-win situation with China replacing low-value jobs with high-value service jobs, while less developed countries with rapidly growing working age populations win market share.

Table 12: China's export share of world trade; selected commodities

% share Textiles Clothing Iron and steel Chemicals Machinery & transport equip. Office & telecom equip. Telecom equip. 1990 4.8 8.9 1.2 1.3 0.9 1.1 na 2001 14.4 18.9 2.4 2.2 3.8 6.2 8.8 2003 20.9 22.4 2.6 2.4 6.4 12.3 14.6 2005 25.9 26.9 6.1 3.2 9.2 17.7 20.4 2008 25.8 33.0 12.0 4.7 12.6 24.3 26.9 2009 28.3 34.0 7.3 4.3 14.0 26.2 29.4

Source: World Trade Organization

Changing composition of growth Below we explore the potential magnitude of deceleration in fixed investment growth if real GDP growth slows to a base case of 7% and the drivers of growth shift from fixed investment to consumption. Assumptions: Real GDP CAGR (2010-20): 7% Consumption, fixed investment and net external demand as a share of GDP return to 2000 levels (see Table 13).

Figure 15: China labor productivity growth (%)

15.0 14.0 13.0 12.0 11.0 10.0 9.0 8.0 7.0 6.0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

Results: Fixed investment CAGR decelerates from 12.7% to 4.7% (2000-10). Consumption CAGR increases from 8.5% to 8.9% (2000-10). Private consumption CAGR increases from 7.5% to 10%. Net exports CAGR decelerates from 11% to 6% (2000-10)

Source: International Labor Organization

Figure 16: China export price index (%oya, nsa)

15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

Source: J.P. Morgan economics.

Net external demand contributed an average 0.7% to real GDP growth in the last decade. In this decade if Chinese wage growth exceeds other EMs then net external demand may be negative.

Table 13: Potential consumption and investment CAGR (2010-20)

% Share of GDP in 2000 Share of GDP in 2010 Assumed share in 2020 CAGR (00-10) CAGR forecast (10-20) Real GDP Consn 56 47 56 8.5 8.9 Fixed Inv 38 47 38 12.7 4.7 Ext Dd 5 5 5 11.4 6.1

10.5 7

Source: J.P. Morgan economics, strategy.

10

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Cheap money and high ICOR The Incremental Capital Output Ratio is domestic investments divided by the change in real GDP. Chinas ICOR has been rising in the last three years. It has averaged 4.0 in the high growth period since 1979. This is higher than the ICOR in Korea, Taiwan and Japan during their respective high growth periods (See Table 14). Twice EM fixed investment to GDP ratio China fixed investment to GDP ratio is twice the EM average (see Table 15). Excess savings help fund this investment via the banking. The rapid rise in profits relative to GDP (Figure 10) provided the cash for reinvestment. As household income to GDP rises there will be a corresponding decline in profits to GDP. The low return on savings is a drag on consumption. Individuals save to meet future liabilities. The largest liability is their pension. Today bank deposit rates are more than 10% lower than nominal wage growth. The result is that individuals are forced to save larger and larger portion of their income in order to have sufficient capital to retire. It may be counterintuitive, but China needs higher interest rates to boost consumption. Its investment in human capital permits China to break away from its investment-led growth model. The risk is that the ministries and industries which thrive with investments are unwilling to reduce their share of GDP. Potential risks of this are poor allocation of capital and inflation.

Table 14: Real GDP growth, ICOR and average CPI during high growth periods

High growth period 1979-2010 1965-1990 1965-1990 1956-1970 1991-2010 Avg Real GDP growth % 9.9 8.8 8.9 9.9 6.9 Average ICOR 4.0 3.3 2.0 2.6 4.0 Average Annual CPI % 6.02 6.36 11.62 9.12 6.35

China* Taiwan Korea Japan** India

Source: J.P. Morgan economics, Bloomberg

Figure 17: China FAI breakdown

70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 2004 2005 2006 Priv ate and JV 2007 2008 2009 Collectiv e 2010 2011

State Ow ned

Source: J.P. Morgan economics

Table 15: Contribution to real GDP: China the outlier

Countries Argentina Brazil Chile China Colombia Czech Republic Hungary India Indonesia Malaysia Mexico Peru Philippines Poland Russia South Africa South Korea Taiwan Thailand Turkey Consumption 78% 82% 84% 48% 81% 71% 72% 73% 66% 66% 81% 75% 86% 79% 77% 84% 67% 66% 60% 81% Fixed Investment 23% 21% 28% 47% 24% 27% 13% 33% 24% 23% 22% 25% 21% 23% 22% 22% 27% 19% 22% 20% Net trade -1% -3% -11% 5% -5% 2% 15% -6% 9% 11% -3% 0% -6% -2% 1% -6% 6% 15% 19% -1%

Source: J.P. Morgan economics: Note: In Figure 9: From consumption to investment nominal rather real GDP is used to calculate the ratio.

11

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Impact on commodity demand If fixed asset investment real growth slows from 12.7% to 4.7% in 2010s then Chinas demand for commodities will slow. In Table 16 we assume 4.7% growth in Chinas commodity demand. The difference in global demand, between the J.P. Morgans base case and the rebalance scenario in 2015, ranges from -12% (aluminium) to -3% (iron ore).

Figure 18: China ICOR

8 6 4 2 0 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009

Table 16: How slower investment could reduce commodity demand base case and 4.8% growth

2000 2010 2015e CAGR (2000-10) China CAGR (201015) base case Total CAGR (201015) base case Base case 2015 total volume Rebalance scenario volume Reduction Aluminium 13 41 49 17.5 10.8 7.0 58209 51360 -12% Nickel 33 41 20.5 10.4 5.6 1979 1791 -9% Copper 12 37 42 14.6 6.2 4.0 23359 22735 -3% Iron ore 20 57 57 19.9 5.8 5.8 2636 2567 -3%

Source: J.P. Morgan estimates, J.P. Morgan EM equity strategy team calculations

Source: J.P. Morgan economics.

12

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Chinas export sector copes with rising wages

Grace Ng (852) 2800-7002. March 4, 2011 Tradable goods inflation has been modest so far, but rising wages have begun to affect production costs. Rising export prices in 2007-08 largely reflected stronger CNY; this time domestic inflation plays a major role. total manufacturing sector wage payments by secondary industry GDP output (in nominal terms).

Figure 19: China export prices and US import prices from China

%oya, both scales 16 12 8 4 0 -4 -8 -12 Jan 05 Jul 06 Feb 08 Sep 09 China export prices, Yuan (LHS) China export prices, USD (LHS) US import prices from China, USD terms (RHS) 6.0 4.0 2.0 0.0 -2.0 -4.0 Apr 11

Export sector manages to move up value-added chain amid rising costs, with profit margins on the rise. As part of the growing global attention being paid to Chinas inflation, there is increasing concern that domestic inflation is being transmitted abroad through rising export prices. The latest US data showed that consumer goods import prices have begun to turn up on the back of rising prices in China. The broader worry is that overheating risks in the EM world will place significant upward pressure on DM consumer goods prices. Alternatively, for Chinas trade sector, the worry is that, faced with upward pressure on domestic production costs, which has become a more dominant concern than the gradual appreciation of the CNY/USD exchange rate, Chinese exporters may begin to lose export market share in the global economy. Chinas inflation: domestic vs. trade sector For Chinas inflation, we have highlighted that, in addition to near-term pressure from rising food prices, the recent upward trend in nonfood inflation has been notable as well: the nonfood CPI rose 2.6%oya in January, the fastest rise in 13 years. Within the nonfood CPI, however, it is the domestic service sector, in particular the housing component, that has been rising the fastest, with the housing CPI up 6.8%oya in January. Meanwhile, our estimate for the major consumer goods CPI component, which reflects the pricing trend in the tradables sector and is more relevant to Chinas export prices, rose a modest 0.5%oya in January, gradually emerging from the prevalent deflationary trend seen in recent years. Along with that, Chinas export price index in yuan terms (that is, before reflecting the currency effect) rose 4.7%oya 3mma by January. While the price increase in the tradable goods sector has been modest compared to overall domestic service prices, reflecting persistent, entrenched excess capacity in a number of manufacturing industries over the years, the general costs of production in Chinas manufacturing sector, including wages, have been rising. We constructed a measure of wage cost pressure by dividing

Source: J.P. Morgan economics

Figure 20: Export price trends - China, Korea and Taiwan

%oya, USD terms 20 China 10 0 -10 -20 -30 06 07 08 09 11 Taiwan Korea

Source: J.P. Morgan economics

Figure 21: Manufacturing wages relative to industry output

108 106 104 102 100 98 96 05Q1 06Q1 06Q1 07Q1 08Q1 09Q1 10Q1

Source: J.P. Morgan economics

This ratio should reflect the trend in labor cost per unit of secondary industry output (dominated by manufacturing). Interestingly, while this measure was relatively stable during 2005-08 (except during the financial crisis period, when it fell somewhat), the index started to pick up

13

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

rather notably since early 2009. This trend to some extent reflects the gradual rise in overall labor cost in the manufacturing sector during the past two years. Regarding the implications for Chinas export prices, broadly speaking, the recent pace of gain in Chinas export prices has been generally in line with that in other major exporters in EM Asia such as Taiwan and Korea, as improving global demand allows Asian exporters to lift prices at a gradual pace.As such, the pace of gain in US$ export prices in over-year-ago terms is approaching the recent peak seen during 2H07-1H08. Meanwhile, this time the rise in Chinas export prices has been largely driven by the gradual rise in domestic prices, while in 2007-08 the notable appreciation in the CNY/USD exchange rate played an important role in the rise in Chinas US$ export prices (CNY/USD appreciated by about 10% between mid-2007 and mid-2008). This suggests that, in addition to the gradual, moderate rise in Chinas tradable goods prices, as the pace of CNY appreciation picks up further (we expect CNY/USD to rise about 5% this year), along with expected solid global demand, there could be more upward pressure on Chinas export prices (in US$ terms). Exporters adapting to rising wages The encouraging news is that despite growing concerns over rising production costs (hence the pressure to raise export prices), Chinas share of the US (and global) market, which had expanded significantly over the past decade, remained at an elevated level through 2010. In addition, profit margins for Chinas industrial enterprises, which suffered notably during the global financial crisis, have rebounded swiftly during the past two years. Indeed, profit margins for the export-related industrial enterprises in particular have advanced notably, significantly exceeding the average pre-crisis level. The fact that Chinas export sector is holding up well, despite growing cost concerns, has come on the back of steady industrial upgrading and moving up the value-added chain. Indeed, while the share of Chinas exports of lower end consumer goods (such as textiles and clothing) in the global market seems to be gradually peaking, Chinas share of the global market in many higher valueadded industries, such as machinery and high-tech sectors, has continued to expand in recent years. Another way Chinese exporters have attempted to manage production costs has been to move inland, where costs of labor and land are generally lower than in the coastal area. Indeed, a growing number of large-scale

US, European, and Asian manufacturers have moved part of their coastal production lines to the central and western parts of the country, with migration speeding up considerably over the past two years. As the Chinese government is set to speed up the urbanization process and infrastructure spending in inland regions under the 12th five-year plan, the improvement in the transportation network should further encourage manufacturers to move inland.

Figure 22: Share of US import market

% share, 12-month moving average 20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 Japan EM Asia (ex-China) China Mexico

Source: J.P. Morgan economics

Figure 23: Industrial enterprise profit margin

7 6 5 4 3

Export-related industrial enterprises % of sales rev enue, 3mma Overall industrial enterprises

2

03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

Source: J.P. Morgan economics

Figure 24: China exports by region

% share of total exports, 12mma, both scales 92.5 Coastal region (LHS) 92.0 91.5 91.0 90.5 90.0 89.5 00 02 Western and central region (RHS) 04 06 08 11 10.5 10.0 9.5 9.0 8.5 8.0 7.5

Source: J.P. Morgan economics

14

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Table 17: Summary of key population data

Size (million) Population Working age population Over 60 population Over 60 population (%) Urban population Urban population Household size Urban households Change (millions) Population Working age population Over 60 population Urbanisation rate Urban population Household size Urban households CAGR (%) Population Working age population Over 60 population Urban population Household size Urban households Annual change (millions) Population Working age population Over 60 population Urban population Urban households Education Total population Total working age population Graduate ratio Graduates Non-graduates working age Change graduates Change non-grad' working age Change graduates (%) Change non-grad' working age (%)

Source: China NBS, US Census, J.P. Morgan Calculations

1990 1,148 724 63 5% 26% 299 3.7 81 1990

2000 1,264 819 86 7% 36% 455 3.4 132 2000 115 96 23 156 -0.26 52

2010 1,330 921 115 9% 50% 665 3.1 215 2010 67 102 29 14% 210 -0.34 82 2010 0.5% 1.2% 2.9% 3.9% -1.0% 5.0% 2010 6.7 10.2 2.9 21.0 8.2 2010 1,330 921 8.9% 118.8 802 73 28 160.3% 3.7%

2020 1,385 905 172 12% 62% 851 3.1 275 2020 54 -16 57 12% 186 0.00 60 2020 0.4% -0.2% 4.1% 2.5% 0.0% 2.5% 2020 5.4 -1.6 5.7 18.6 6.0 2020 1,385 905 14.0% 193.8 711 75 -91 63.1% -11.4%

2030 1,391 830 239 17% 68% 950 3.1 306 2030 7 -74 67 7% 98 0.00 32 2030 0.1% -0.9% 3.3% 1.1% 0.0% 1.1% 2030 0.7 -7.4 6.7 9.8 3.2 2030 1,391 830 19.3% 268.8 562 75 -149 38.7% -21.0%

2040 1,359 766 327 24% 76% 1,029 3.1 332 2040 -33 -64 88 8% 80 0.00 26 2040 -0.2% -0.8% 3.2% 0.8% 0.0% 0.8% 2040 -3.3 -6.4 8.8 8.0 2.6 2040 1,359 766 25.3% 343.8 422 75 -139 27.9% -24.8%

1990

2000 1.0% 1.2% 3.2% 4.3% -0.7% 5.1% 2000 11.5 9.6 2.3 15.6 5.2 2000 1,264 819 3.6% 45.6 774 11 84 32.4% 12.2%

1990

1990 1,148 724 3.0% 34.5 689

15

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Methodology 1. We adjust per capita GDP to todays US$. We do this by inflating the historical per capita GDP by current deflator and converting to US$ using current exchange rate 2. The centered moving average is calculated as the average of current year, previous two years and next two years real GDP growth

Figure 25: Lessons from other countries - Real GDP growth (5-year centered moving average %) vs. adjusted per capita GDP (US$)

Real GDP grow th 5-y ear centered moving average % 16

China (1978-2010) Taiw an (1960-2010)

US (1948-2010) South Korea (1960-2010) Poly . (Curve fit)

Japan (1956-2010) Hong Kong (1963-2010)

14

Singapore (1960-2010)

12

10

-2 0 10000 20000 30000 Adjusted GDP per capita US$

Source: J.P. Morgan economics. Note The fitted curve excludes Singapore data points.

40000

50000

16

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 26: Real GDP growth %oya (five-year centered moving average) over time

Real GDP grow th 5-y ear centered moving average % 16

US China

Japan South Korea

Hong Kong Taiw an

Singapore

14

12

10

-2 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10

Source: J.P. Morgan economics

17

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 27: Relative growth and wealth of provinces in China

2010 GDP Growth 17.4% 17.1% 15.8% 15.3% 15.1% 14.9% 14.8% 14.5% 14.5% 14.5% 11.8% 11.7% 10.6% 10.2% 9.9%

Province Tianjin Chongqing

Heilongjiang

Hainan Qinghai Sichuan Inner Mongolia Hubei Hunan Anhui Shaanxi Zhejiang Gansu Xinjiang Beijing Shanghai

Jilin Inner Mongolia Liaoning Xinjiang Beijing Tianjin Hebei Ningxia Shanxi Shandong Qinghai Gansu Henan Shaanxi Hubei Chongqing Hunan Guizhou Yunnan Jiangxi Fujian Jiangsu Anhui Shanghai Zhejiang

Tibet Sichuan GDP per capital (RMB) 60,000 80,000 40,000 60,000 20,000 40,000 0 20,000

Source: CEIC, J.P. Morgans Hands of China Team

Guangxi Guangdong

Hainan

18

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 28: Real GDP growth vs. Average CPI in the previous decades

Real GDP grow th % 12 China (2001 - 2010) China (1991 - 2001)

10

8 China (1981 - 1990)

4 China 2 Taiw an Singapore US South Korea Japan Hong Kong

0 -1 1 3 5 7 9 Av erage CPI % 11 13 15 17 19

Source: J.P. Morgan economics, Bloomberg

19

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 29: Intensity of cement use; per-capita consumption of cement (tonnes) vs. adjusted per-capita nominal GDP

Cement consumption per capita (tonnes) 1.4 China 2010 E 1993: per capita cement consumption peaked in Taiwan 1.2 China 2009

Russia (1991-2009E)

1997: per capita cement consumption peaked in Korea

Brazil (1985-2009E) India (1985-2009E) China (1985-2010E) US (1930-2008) UK (1985-2009E) Germany (1985-2009E) Japan (1985-2009E) Taiwan (1985-2009)

1.0 S. Korea 2009E 0.8

South Korea (1985-2009E) Mexico (1985-2009E)

Japan 2009E

0.6 Russia 2009E 0.4 Mexico 2009E Taiwan 2009 Germany 2009E

0.2 Brazil 2009E India 2009E 0.0 0 6000 12000 18000 24000 30000 GDP per capita (USD) 36000 42000 48000 UK 2009E US 2008

Source: US Geological Survey and J.P. Morgan estimates. Note: The GDP per capita is restated for todays dollars by adjusting the deflator series.

20

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 30: Intensity of steel use; per-capita consumption of steel (lbs) vs. adjusted per-capita nominal GDP

Per capita consumption of steel (lbs) 3,000 1993: per capita steel consumption peaked in Taiwan

South Korea (1970 - 2009E) United States (1950 - 2009E)

2008: per capita steel consumption peaked in Korea 2,500

Taiwan (1977 - 2009E) Japan (1956 - 2009E) Germany (1968 - 2009E) China (1983 - 2009E)

2,000

S. Korea 2009E

India (1978 - 2009E)

1,500

Taiwan 2009E

Japan 2009E

1,000 China 2009E Germany 2009E 500 U.S. 2009E

India 2009E 0 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 30,000 35,000 40,000 45,000 50,000

GDP per capita (US$)

Source: CRU and J.P. Morgan estimates. Note: The GDP per capita is restated for todays dollars by adjusting the deflator series.

21

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 31: Per-capita consumption of oil (barrels per day per 1000 population) vs. adjusted per-capita nominal GDP

Barrels per day per 1000 population 80

Russia (1991-2009) Brazil (1982-2009) India (1965-2009) China (1978-2009) US (1965-2009) UK (1965-2009) Germany (1968-2009) Japan (1965-2009) Taiwan (1965-2009) South Korea (1965-2009) South Africa (1965-2009)

60

S. Korea 2009

Japan 2009 Taiwan 2009

US 2009

40

Russia 2009

20

UK 2009 Germany 2009

Brazil 2009 China 2009 South Africa 2009 12000 18000 24000 30000 GDP per capita (USD) 36000 42000 48000

0 0 6000

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2010

22

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 32: Total energy consumption in China higher than in the US but low at a per-capita level; per-capita consumption of primary energy (tonnes of oil equivalent) vs. per adjusted capita nominal GDP

energy consumed per capita (tonnes of oil equivalent) 9

Brazil (1982-2009) India (1965-2009) China (1978-2009) South Africa (1965-2009) US (1965-2009) UK (1965-2009) Germany (1968-2009) Japan (1965-2009) Taiwan (1965-2009) South Korea (1965-2009) Russia (1991-2009)

US 2009

S. Korea 2009

Russia 2009

Taiwan 2009

Japan 2009

4 South Africa 2009 3

Germany 2009

2

UK 2009

1 India 2009 0 6000 China 2009

Brazil 2009

12000

18000

24000

30000

36000

42000

48000

GDP per capita (USD)

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2010. Note: Primary energy comprises commercially traded fuels only. Excluded, therefore, are fuels such as wood, peat and animal waste. Also excluded are wind, geothermal and solar power generation.

23

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 33: Mobile subscription per 100 people vs. adjusted per capita nominal GDP

Mobile subscription per 100 people 180 Russia 2009 160 Taiwan 2009 140 UK 2009 120 South Korea 2009 100 US 2009 80 India 2009 Brazil 2009 60

US (1989 - 2009) UK (1989 - 2009) Brazil (1992 - 2009) India (1995 - 2009) China (1992 - 2009) South Korea (1989 - 2009) Taiwan (1989 - 2009) Russia (1993 - 2009)

40

China 2009

20

0 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 30,000 35,000 40,000 45,000 50,000 GDP per capita (USD)

Source: Bloomberg. Note: Subscriber data is not adjusted for individuals using multiple SIM cards

24

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 34: China is already the worlds largest car marketbut still low per 1000 people; passenger cars per 1000 people vs. adjusted per capita nominal GDP

Passenger cars per 1000 population 900

US (1930-2007) Germany (1995-2006) Italy (1995-2006)

US 2007

800

UK (1995-2006) Japan (1970-2008) South Korea (1970-2008) India (2001-2008) China (1991-2008)

700

600

Italy 2006 Germany 2006

500

400

UK 2006

Korea 2008

300

200

India 2008 (8)

China 2014 E

Japan 2008

100

China 2008

0 0 10000 20000 30000 GDP per capita (USD)

Source: J.P. Morgan estimates, Eurostat, US Department of Energy. Note: China 2014 forecast from J.P. Morgan China Autos team. GDP per capita data is adjusted for inflation.

40000

50000

25

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Figure 35: Share of global nominal GDP (%) Chinas share is 10% in 2010 and forecast to be 17% in 2020

100%

ROW

90% 80%

Other EM Japan

70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10%

Developed Europe

US (2000: 31%, 2010: 24%; 2020: 19%) Brazil

India Russia

China (2000:4%, 2010: 10%; 2020F: 17%)

0% 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Source: J.P. Morgan economics, IMF. Note: Regions follow MSCI country definitions. The projections assume nominal GDP growth at potential real GDP growth and central banks inflation target. To compute FX for periods beyond 2011, we assume the normalization of REER over the forecasted period.

26

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

27

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

Analyst Certification: The research analyst(s) denoted by an AC on the cover of this report certifies (or, where multiple research analysts are primarily responsible for this report, the research analyst denoted by an AC on the cover or within the document individually certifies, with respect to each security or issuer that the research analyst covers in this research) that: (1) all of the views expressed in this report accurately reflect his or her personal views about any and all of the subject securities or issuers; and (2) no part of any of the research analysts compensation was, is, or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed by the research analyst(s) in this report.

Important Disclosures

Explanation of Equity Research Ratings and Analyst(s) Coverage Universe: J.P. Morgan uses the following rating system: Overweight [Over the next six to twelve months, we expect this stock will outperform the average total return of the stocks in the analysts (or the analysts teams) coverage universe.] Neutral [Over the next six to twelve months, we expect this stock will perform in line with the average total return of the stocks in the analysts (or the analysts teams) coverage universe.] Underweight [Over the next six to twelve months, we expect this stock will underperform the average total return of the stocks in the analysts (or the analysts teams) coverage universe.] J.P. Morgan Cazenoves UK Small/Mid-Cap dedicated research analysts use the same rating categories; however, each stocks expected total return is compared to the expected total return of the FTSE All Share Index, not to those analysts coverage universe. A list of these analysts is available on request. The analyst or analysts teams coverage universe is the sector and/or country shown on the cover of each publication. See below for the specific stocks in the certifying analyst(s) coverage universe.

J.P. Morgan Equity Research Ratings Distribution, as of March 31, 2011 Overweight (buy) 47% 50% 43% 70% Neutral (hold) 42% 45% 49% 62% Underweight (sell) 11% 33% 8% 56%

J.P. Morgan Global Equity Research Coverage IB clients* JPMS Equity Research Coverage IB clients*

*Percentage of investment banking clients in each rating category. For purposes only of FINRA/NYSE ratings distribution rules, our Overweight rating falls into a buy rating category; our Neutral rating falls into a hold rating category; and our Underweight rating falls into a sell rating category.

Valuation and Risks: Please see the most recent company-specific research report for an analysis of valuation methodology and risks on any securities recommended herein. Research is available at http://www.morganmarkets.com , or you can contact the analyst named on the front of this note or your J.P. Morgan representative. Analysts Compensation: The equity research analysts responsible for the preparation of this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including the quality and accuracy of research, client feedback, competitive factors, and overall firm revenues, which include revenues from, among other business units, Institutional Equities and Investment Banking. Registration of non-US Analysts: Unless otherwise noted, the non-US analysts listed on the front of this report are employees of non-US affiliates of JPMS, are not registered/qualified as research analysts under FINRA/NYSE rules, may not be associated persons of JPMS, and may not be subject to FINRA Rule 2711 and NYSE Rule 472 restrictions on communications with covered companies, public appearances, and trading securities held by a research analyst account.

Other Disclosures

J.P. Morgan ("JPM") is the global brand name for J.P. Morgan Securities LLC ("JPMS") and its affiliates worldwide. J.P. Morgan Cazenove is a marketing name for the U.K. investment banking businesses and EMEA cash equities and equity research businesses of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and its subsidiaries. Options related research: If the information contained herein regards options related research, such information is available only to persons who have received the proper option risk disclosure documents. For a copy of the Option Clearing Corporations Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options, please contact your J.P. Morgan Representative or visit the OCCs website at http://www.optionsclearing.com/publications/risks/riskstoc.pdf. Legal Entities Disclosures U.S.: JPMS is a member of NYSE, FINRA and SIPC. J.P. Morgan Futures Inc. is a member of the NFA. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. is a

28

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

member of FDIC and is authorized and regulated in the UK by the Financial Services Authority. U.K.: J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. (JPMSL) is a member of the London Stock Exchange and is authorized and regulated by the Financial Services Authority. Registered in England & Wales No. 2711006. Registered Office 125 London Wall, London EC2Y 5AJ. South Africa: J.P. Morgan Equities Limited is a member of the Johannesburg Securities Exchange and is regulated by the FSB. Hong Kong: J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited (CE number AAJ321) is regulated by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the Securities and Futures Commission in Hong Kong. Korea: J.P. Morgan Securities (Far East) Ltd, Seoul Branch, is regulated by the Korea Financial Supervisory Service. Australia: J.P. Morgan Australia Limited (ABN 52 002 888 011/AFS Licence No: 238188) is regulated by ASIC and J.P. Morgan Securities Australia Limited (ABN 61 003 245 234/AFS Licence No: 238066) is a Market Participant with the ASX and regulated by ASIC. Taiwan: J.P.Morgan Securities (Taiwan) Limited is a participant of the Taiwan Stock Exchange (company-type) and regulated by the Taiwan Securities and Futures Bureau. India: J.P. Morgan India Private Limited, having its registered office at J.P. Morgan Tower, Off. C.S.T. Road, Kalina, Santacruz East, Mumbai - 400098, is a member of the National Stock Exchange of India Limited (SEBI Registration Number - INB 230675231/INF 230675231/INE 230675231) and Bombay Stock Exchange Limited (SEBI Registration Number - INB010675237/INB010675237) and is regulated by Securities and Exchange Board of India. Thailand: JPMorgan Securities (Thailand) Limited is a member of the Stock Exchange of Thailand and is regulated by the Ministry of Finance and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Indonesia: PT J.P. Morgan Securities Indonesia is a member of the Indonesia Stock Exchange and is regulated by the BAPEPAM LK. Philippines: J.P. Morgan Securities Philippines Inc. is a member of the Philippine Stock Exchange and is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Brazil: Banco J.P. Morgan S.A. is regulated by the Comissao de Valores Mobiliarios (CVM) and by the Central Bank of Brazil. Mexico: J.P. Morgan Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., J.P. Morgan Grupo Financiero is a member of the Mexican Stock Exchange and authorized to act as a broker dealer by the National Banking and Securities Exchange Commission. Singapore: This material is issued and distributed in Singapore by J.P. Morgan Securities Singapore Private Limited (JPMSS) [MICA (P) 025/01/2011 and Co. Reg. No.: 199405335R] which is a member of the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited and is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and/or JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., Singapore branch (JPMCB Singapore) which is regulated by the MAS. Malaysia: This material is issued and distributed in Malaysia by JPMorgan Securities (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd (18146-X) which is a Participating Organization of Bursa Malaysia Berhad and a holder of Capital Markets Services License issued by the Securities Commission in Malaysia. Pakistan: J. P. Morgan Pakistan Broking (Pvt.) Ltd is a member of the Karachi Stock Exchange and regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan. Saudi Arabia: J.P. Morgan Saudi Arabia Ltd. is authorized by the Capital Market Authority of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (CMA) to carry out dealing as an agent, arranging, advising and custody, with respect to securities business under licence number 35-07079 and its registered address is at 8th Floor, Al-Faisaliyah Tower, King Fahad Road, P.O. Box 51907, Riyadh 11553, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Dubai: JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., Dubai Branch is regulated by the Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA) and its registered address is Dubai International Financial Centre - Building 3, Level 7, PO Box 506551, Dubai, UAE. Country and Region Specific Disclosures U.K. and European Economic Area (EEA): Unless specified to the contrary, issued and approved for distribution in the U.K. and the EEA by JPMSL. Investment research issued by JPMSL has been prepared in accordance with JPMSL's policies for managing conflicts of interest arising as a result of publication and distribution of investment research. Many European regulators require a firm to establish, implement and maintain such a policy. This report has been issued in the U.K. only to persons of a kind described in Article 19 (5), 38, 47 and 49 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 (all such persons being referred to as "relevant persons"). This document must not be acted on or relied on by persons who are not relevant persons. Any investment or investment activity to which this document relates is only available to relevant persons and will be engaged in only with relevant persons. In other EEA countries, the report has been issued to persons regarded as professional investors (or equivalent) in their home jurisdiction. Australia: This material is issued and distributed by JPMSAL in Australia to wholesale clients only. JPMSAL does not issue or distribute this material to retail clients. The recipient of this material must not distribute it to any third party or outside Australia without the prior written consent of JPMSAL. For the purposes of this paragraph the terms wholesale client and retail client have the meanings given to them in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001. Germany: This material is distributed in Germany by J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd., Frankfurt Branch and J.P.Morgan Chase Bank, N.A., Frankfurt Branch which are regulated by the Bundesanstalt fr Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht. Hong Kong: The 1% ownership disclosure as of the previous month end satisfies the requirements under Paragraph 16.5(a) of the Hong Kong Code of Conduct for Persons Licensed by or Registered with the Securities and Futures Commission. (For research published within the first ten days of the month, the disclosure may be based on the month end data from two months prior.) J.P. Morgan Broking (Hong Kong) Limited is the liquidity provider/market maker for derivative warrants, callable bull bear contracts and stock options listed on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited. An updated list can be found on HKEx website: http://www.hkex.com.hk. Japan: There is a risk that a loss may occur due to a change in the price of the shares in the case of share trading, and that a loss may occur due to the exchange rate in the case of foreign share trading. In the case of share trading, JPMorgan Securities Japan Co., Ltd., will be receiving a brokerage fee and consumption tax (shouhizei) calculated by multiplying the executed price by the commission rate which was individually agreed between JPMorgan Securities Japan Co., Ltd., and the customer in advance. Financial Instruments Firms: JPMorgan Securities Japan Co., Ltd., Kanto Local Finance Bureau (kinsho) No. 82 Participating Association / Japan Securities Dealers Association, The Financial Futures Association of Japan. Korea: This report may have been edited or contributed to from time to time by affiliates of J.P. Morgan Securities (Far East) Ltd, Seoul Branch. Singapore: JPMSS and/or its affiliates may have a holding in any of the securities discussed in this report; for securities where the holding is 1% or greater, the specific holding is disclosed in the Important Disclosures section above. India: For private circulation only, not for sale. Pakistan: For private circulation only, not for sale. New Zealand: This material is issued and distributed by JPMSAL in New Zealand only to persons whose principal business is the investment of money or who, in the course of and for the purposes of their business, habitually invest money. JPMSAL does not issue or distribute this material to members of "the public" as determined in accordance with section 3 of the Securities Act 1978. The recipient of this material must not distribute it to any third party or outside New Zealand without the prior written consent of JPMSAL. Canada: The information contained herein is not, and under no circumstances is to be construed as, a prospectus, an advertisement, a public offering, an offer to sell securities described herein, or solicitation of an offer to buy securities described herein, in Canada or any province or territory thereof. Any offer or sale of the securities described herein in Canada will be made only under an exemption from the requirements to file a prospectus with the relevant Canadian securities regulators and only

29

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

by a dealer properly registered under applicable securities laws or, alternatively, pursuant to an exemption from the dealer registration requirement in the relevant province or territory of Canada in which such offer or sale is made. The information contained herein is under no circumstances to be construed as investment advice in any province or territory of Canada and is not tailored to the needs of the recipient. To the extent that the information contained herein references securities of an issuer incorporated, formed or created under the laws of Canada or a province or territory of Canada, any trades in such securities must be conducted through a dealer registered in Canada. No securities commission or similar regulatory authority in Canada has reviewed or in any way passed judgment upon these materials, the information contained herein or the merits of the securities described herein, and any representation to the contrary is an offence. Dubai: This report has been issued to persons regarded as professional clients as defined under the DFSA rules. General: Additional information is available upon request. Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively J.P. Morgan) do not warrant its completeness or accuracy except with respect to any disclosures relative to JPMS and/or its affiliates and the analysts involvement with the issuer that is the subject of the research. All pricing is as of the close of market for the securities discussed, unless otherwise stated. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. The opinions and recommendations herein do not take into account individual client circumstances, objectives, or needs and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities or financial instruments mentioned herein. JPMS distributes in the U.S. research published by non-U.S. affiliates and accepts responsibility for its contents. Periodic updates may be provided on companies/industries based on company specific developments or announcements, market conditions or any other publicly available information. Clients should contact analysts and execute transactions through a J.P. Morgan subsidiary or affiliate in their home jurisdiction unless governing law permits otherwise. Other Disclosures last revised January 8, 2011.

Copyright 2011 JPMorgan Chase & Co. All rights reserved. This report or any portion hereof may not be reprinted, sold or redistributed without the written consent of J.P. Morgan.#$J&098$#*P

30

Adrian Mowat (852) 2800-8599 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com

Emerging Markets Equity Research 31 May 2011

J.P. Morgan Equity Strategy and Asia Pacific Macro Team

Chief Equity Strategists Adrian Mowat Ben Laidler David Aserkoff Frontier Markets Sriyan Pietersz Brian Chase Christian Kern Developed Markets Thomas J Lee Mislav Matejka Hajime Kitano Country Strategists Paul Brunker Frank Li Aditya Srinath Bharat Iyer Christopher Gee Scott Seo Hoy Kit Mak Gilbert Lopez Nick Lai Sriyan Pietersz Regional Sector Research Frank Li Ebru Sener Sunil Garg Brynjar Bustnes Christopher Gee Corrine Png JJ Park James Sullivan Boris Kan Economic & Policy Research David G. Fernandez Masaaki Kanno Jahangir Aziz Jiwon Lim Qian Wang Stephen Walters Commodities Research Colin P. Fenton Rates Research Bert Gochet Yen Ping Ho Credit Markets Research David G. Fernandez Andrea Cheng Asia and Emerging Markets Latin America CEEMEA ASEAN and Frontier Markets Southern Cone & Andean MENA US Europe Japan Australia China Indonesia India Singapore Korea Malaysia Philippines Taiwan Thailand Autos & Auto Parts Consumer & Media Financials Oil & Gas Real Estate Transportation Technology Telecommunications Utilities Emerging Asia Japan India Korea China, HK and Taiwan Australia Global Commodities Research and Strategy Emerging Asia, Rates Strategy Emerging Asia, Forex Strategy Emerging Asia, Sovereigns Emerging Asia, Banking (852) 2800 8599 (212) 622 5252 (44-20) 7325-1775 (66-2) 684 2670 (562) 425 5245 (971) 4428 1789 (1) 212 622 6505 (44-20) 7325 5242 (81-3) 5545 8655 (61-2) 9220 1638 (852) 2800 8511 (62-21) 5291 8573 (9122) 6157 3600 (65) 6882-2345 (82-2) 758 5759 (60-3) 2270 4728 (63-2) 8781 188 (886-2) 27259864 (66-2) 684 2670 (852) 2800 8511 (852) 2800 8521 (852) 2800 8518 (852) 2800-8578 (65) 6882-2345 (65) 6882 1514 (822) 758-5717 (65) 6882 2374 (852) 2800 8573 (65) 6882 2461 (81-3) 5573 1166 (9122) 6157 3385 (82-2) 758 5509 (852) 2800 7009 (61-2) 9220 1599 (1-212) 834 5648 (852) 2800 8325 (65) 6882 2216 (65) 6882 2461 (852) 2800 8028 adrian.mowat@jpmorgan.com ben.m.laidler@jpmchase.com david.aserkoff@jpmorgan.com sriyan.pietersz@jpmorgan.com brian.p.chase@jpmorgan.com christian.a.kern@jpmorgan.com thomas.lee@jpmorgan.com mislav.matejka@jpmorgan.com hajime.x.kitano@jpmorgan.com paul.m.brunker@jpmorgan.com frank.m.li@jpmorgan.com aditya.s.srinath@jpmchase.com bharat.x.iyer@jpmorgan.com christopher.ka.gee@jpmorgan.com scott.seo@jpmorgan.com hoykit.mak@jpmorgan.com lopez.y.gilbert@jpmorgan.com nick.yc.lai@jpmorgan.com sriyan.pietersz@jpmorgan.com frank.m.li@jpmorgan.com ebru.sener@jpmorgan.com sunil.garg@jpmorgan.com brynjar.e.bustnes@jpmorgan.com christopher.ka.gee@jpmorgan.com corrine.ht.png@jpmorgan.com jj.park@jpmorgan.com james.r.sullivan@jpmorgan.com boris.cw.kan@jpmorgan.com david.g.fernandez@jpmorgan.com masaaki.kanno@jpmorgan.com jahangir.x.aziz@jpmorgan.com jiwon.c.lim@jpmorgan.com qian.li.wang@jpmorgan.com stephen.b.walters@jpmorgan.com colin.p.fenton@jpmorgan.com bert.j.gochet@jpmorgan.com yenping.ho@jpmorgan.com david.g.fernandez@jpmorgan.com andrea.k.cheng@jpmorgan.com

31

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)