Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Resolving The Foreclosure Crisis-Modification of Mortgages in Bankruptcy

Uploaded by

Richarnellia-RichieRichBattiest-CollinsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Resolving The Foreclosure Crisis-Modification of Mortgages in Bankruptcy

Uploaded by

Richarnellia-RichieRichBattiest-CollinsCopyright:

Available Formats

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

RESOLVING THE FORECLOSURE CRISIS: MODIFICATION OF MORTGAGES IN BANKRUPTCY

ADAM J. LEVITIN

This Article empirically tests the economic assumption underlying the policy against bankruptcy modification of home-mortgage debtthat protecting lenders from losses in bankruptcy encourages them to lend more and at lower rates, and thus encourages homeownership. The data show that the assumption is mistaken; permitting modification would have little or no impact on mortgage credit cost or availability. Because lenders face smaller losses from bankruptcy modification than from foreclosure, the market is unlikely to price against bankruptcy modification. In light of market neutrality, the Article argues that permitting modification of home mortgages in bankruptcy presents the best solution to the foreclosure crisis. Unlike any other proposed response, bankruptcy modification offers immediate relief, solves the market problems created by securitization, addresses both problems of payment-reset shock and negative equity, screens out speculators, spreads burdens between borrowers and lenders, and avoids the costs and moral hazard of a government bailout. As the foreclosure crisis deepens, bankruptcy modification presents the best and least invasive method of stabilizing the housing market.

Introduction: Foreclosure, Bankruptcy, and Mortgages ............... 566 I. The Structure of the Mortgage Market ........................... 579 A. Treatment of Mortgages in Bankruptcy ..................... 579 B. Structure of the Modern Mortgage Market ................. 582 II. Bankruptcy-Modification Risk as Reflected in MortgageMarket Pricing ....................................................... 586 A. Mortgage-Interest-Rate Variation by Property Type ...... 586 1. Experiment Design ........................................ 586 2. Experiment Results ........................................ 589 B. Private-Mortgage-Insurance Rate Premiums ............... 593 C. Secondary-Market-Pricing Variation by Property Type .. 597

Associate Professor, Georgetown University Law Center. This Article was supported by grants from the Reynolds Family Fund at the Georgetown University Law Center. This Article has benefited from comments and suggestions from Amy Crews-Cutts, William Bratton, Michael Diamond, Anna Gelpern, Joshua Goodman, Rich Hynes, Gregory Klass, Richard Levin, Sarah Levitin, Ronald Mann, Katherine Porter, Mark Scarberry, Eric Stein, Dom Sutera, Fred Tung, Tara Twomey, William Vukowich, Susan Wachter, and Elizabeth Warren. The Article has also benefited from presentations at the Harvard/University of Texas Conference on Commercial Realities, the Georgetown University Law Center Faculty Workshop, the Research and Statistics Seminar of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the University of Virginia School of Law Faculty Workshop, and the American Law and Economics Associations Annual Convention. Special thanks to Robert P. Enayati, Tai C. Nguyen, and Galina Petrova for research assistance. Please direct comments to alevitin@law.georgetown.edu.

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1071931

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

566

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

D. Historical Impact of Permitting Strip-Down ............... 598 III. Explaining Mortgage-Market Indifference to Bankruptcy Strip-Down ........................................................... 600 A. The Baseline for Loss Comparison: Foreclosure Sales ... 603 B. Projecting Lender Losses in Bankruptcy ................... 606 1. 2001 Consumer Bankruptcy Project Database ......... 607 2. 2007 Riverside-San Bernardino Database .............. 611 IV. Policy Implications .................................................. 618 A. Voluntary Versus Involuntary Modification of Mortgages ....................................................... 618 B. Bankruptcy Modification Compared with Other Policy Responses ....................................................... 626 1. Laissez-Faire Market Self-Correction .................. 627 2. Coordinated Voluntary-Workout Efforts ............... 627 3. Procedural Requirements to Encourage Consensual Workouts .................................................... 627 4. Foreclosure and Rate-Increase Moratoria and Other Limitations on the Foreclosure Process ................ 628 5. Government Modification Following EminentDomain Takings............................................ 631 6. Government Refinancing, Guaranty, or Insurance of Mortgages ................................................... 631 a. FHASecure and HOPE for Homeowners Act ...... 634 b. Homeowner Affordability and Stability Program .. 636 7. The Advantages of Bankruptcy Modification .......... 640 Conclusion .................................................................... 647 Postscript...................................................................... 649 Appendix A: Mortgage-Origination Rate Quotes (Selected) .......... 651 Appendix B: Evaluating the Mortgage Bankers Associations Modification-Impact Claim......................................... 654 INTRODUCTION: FORECLOSURE, BANKRUPTCY, AND MORTGAGES The United States is in the midst of an unprecedented homeforeclosure crisis. At no time since the Great Depression have so many Americans lost their homes, and many millions more are in jeopardy of foreclosure. Nearly 1.7 million homes entered foreclosure in 2007,1

1. HOPE NOW, MORTGAGE LOSS MITIGATION STATISTICS: INDUSTRY EXTRAPOLATIONS (QUARTERLY FOR 2007 AND 2008) (2009), available at http://www.hopenow.com/upload/data/files/HOPE%20NOW%20Loss%20Mitigation% 20National%20Data%20July07%20to%20February09.pdf; see also Press Release, RealtyTrac, Inc., U.S. Foreclosure Activity Increases 75 Percent in 2007 (Jan. 29,

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1071931

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

567

and another 2.2 million entered in the first three quarters of 2008.2 Over half a million homes were actually sold in foreclosure or otherwise surrendered to lenders in 2007,3 and over 900,000 were sold in foreclosure in 2008.4 At the end of 2008, more than one in ten homeowners were either past due or in foreclosure, the highest levels on record.5 By 2012, Credit Suisse predicts around 8.1 million homes, or 16 percent of all residential borrowers, could go through foreclosure.6 Expressed differently, one in every nine homeowners and one in six households that have a mortgagewill lose their home to foreclosure.

2008), available at http://www.realtytrac.com/ ContentManagement/pressrelease.aspx? ChannelID=9&ItemID=3988&accnt=64847 (providing a lower number). 2. HOPE NOW, supra note 1; see also Chris Mayer et al., The Rise in Mortgage Defaults, 23 J. ECON. PERSP. (forthcoming 2009) (noting 1.2 million foreclosure starts in first half of 2008). 3. HOPE NOW, supra note 1; see also E-mail from Daren Blomquist, RealtyTrac, Inc., to author (Mar. 7, 2008) (on file with author). 4. HOPE NOW, supra note 1. 5. See Press Release, Mortgage Bankers Assn, Delinquencies Continue to Climb in Latest MBA National Delinquency Survey (Mar. 5, 2009), available at http://www.mbaa.org/NewsandMedia/PressCenter/68008.htm. Approximately 3.30 percent of all one-to-four-family residential mortgages outstanding were in the foreclosure process in the first quarter of 2008, and 7.88 percent were delinquent. Id.; see also Vikas Bajaj & Michael Grynbaum, A Rising Tide of Mortgage Defaults, Not All on Risky Loans, N.Y. TIMES, June 6, 2008, at C1. Because of the steadily increasing level of homeownership in the United States, see U.S. CENSUS BUREAU, HOUSING VACANCIES AND HOMEOWNERSHIP (CPS/HVS), at tbl. 14 (2008), available at http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/hvs/historic/histt14.html, higher percentages of past-due and foreclosed mortgages mean that an even greater percentage of Americans are directly affected by higher delinquency and foreclosure rates. 6. CREDIT SUISSE FIXED INCOME RESEARCH, FORECLOSURE UPDATE: OVER 8 MILLION FORECLOSURES EXPECTED 1 (Dec. 4, 2008), available at http://www.chapa.org/pdf/ForeclosureUpdateCreditSuisse.pdf. Even Credit Suisses best-case scenario still involves 6.3 million foreclosures. Id. at 7.

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1071931

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

568

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

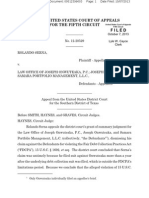

3.5% 3.0% 2.5% 2.0% 1.5% 1.0% 0.5% 0.0%

93 95 96 97 98 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 20 94 19 19 19 19 19 19 19 99 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 08

Chart 1: Percentage of One-to-Four-Family Residential Mortgages in Foreclosure Process7 Both the increase in, and the sheer number of, foreclosures should be alarming, because foreclosures create significant deadweight loss and have major third-party externalities.8 Historically, lenders are estimated to lose from 40 to 50 percent of their investment in a foreclosure situation,9 and in the current market, even greater losses are expected.10 Borrowers lose their homes and are forced to relocate, often

7. Mortgage Bankers Assn, National Delinquency Surveys (on file with author). 8. Anthony Pennington-Cross, The Value of Foreclosed Property, 28 J. REAL ESTATE RES. 19495 (2006) (surveying estimates of deadweight loss on foreclosure). 9. See id.; see also Gretchen Morgenson, Cruel Jokes, and No One Is Laughing, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 13, 2008 (citing historical foreclosure-loss rates of 20 to 40 percent); Posting of Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson to http://www.etrunk.kiev.ua/ask/20071207.html (Dec. 7, 2007). Actual foreclosure losses are difficult to measure consistently because loss reporting may or may not include loss of junk fees and matured interest, rather than a more consistent baseline of unpaid principal. Because most mortgages are held by securitization trusts, the losses to holders of trust securities will vary by tranche. See generally CREDIT SUISSE EQUITY RESEARCH, MORTGAGE LIQUIDITY DU JOUR: UNDERESTIMATED NO MORE (Mar. 12, 2007), available at http://billcara.com/CS%20Mar%2012%202007%20 Mortgage%20and%20Housing.pdf. Some tranches may experience no losses, while other tranches may have complete losses. See generally id. 10. FITCH RATINGS, RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE CRITERIA REPORT: REVISED LOSS EXPECTATIONS FOR 2006 AND 2007 SUBPRIME VINTAGE COLLATERAL 1 (Mar. 25, 2008), available at http://billcara.com/CS%20Mar%2012%202007%20Mortgage%20and% 20Housing.pdf.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

569

to new communities, a move that can place extreme stress on borrowers and their families.11 Foreclosure is an undesirable outcome for borrowers and lenders. Foreclosures also impose costs on third parties. When families have to move to new homes, community ties are rent asunder. Friendships, religious congregations, schooling, childcare, medical care, transportation, and even employment often depend on geography.12 Foreclosures also depress housing and commercial-realestate prices throughout entire neighborhoods. For example, a study on foreclosures in Chicago in the late 1990s concluded that a single foreclosure depressed neighboring properties values between $159,000 and $371,000, or between 0.9% and 1.136% of the property value of all the houses within an eighth of a mile.13 For Chicago, which has a housing density of 5,076 houses per square mile,14 or around 79 per square eighth of a mile, this translates into a single foreclosure costing each of 79 neighbors between $2,012 and $4,696.

11. See, e.g., MINDY THOMPSON FULLILOVE, ROOT SHOCK 1120 (2005) (noting emotional harms from urban renewal); Lorna Fox, Re-Possessing Home: A Reanalysis of Gender, Homeownership and Debtor Default for Feminist Legal Theory, 14 WM. & MARY J. WOMEN & L. 423, 434 (2008) (The impact of losing ones home on an individual occupiers quality of life, social and identity status, personal and family relationships, and for his or her emotional, psychological and physical health and wellbeing have been well established in housing and health literature.); Eric S. Nguyen, Parents in Financial Crisis: Fighting to Keep the Family Home, 82 AM. BANKR. L.J. 229 (2008); Margaret Jane Radin, Property and Personhood, 34 STAN. L. REV. 957, 95859 (1982) (observing that control over property like homes that are bound up with ones self is essential for psychological well-being). For a critical review of the literature on homes and psychology see Stephanie Stern, Residential Protectionism and the Legal Mythology of Home, 107 MICH. L. REV. (forthcoming 2009); see also Michael Levenson, The Anguish of Foreclosure: Fearing Sale of House, Woman Kills Herself Before the Auction, BOSTON GLOBE, July 24, 2008, at B1; Ohio Woman, 90, Attempts Suicide After Foreclosure, REUTERS, Oct. 3, 2008. 12. See Phillip Lovell & Julia Isaacs, The Impact of the Mortgage Crisis on Children, FIRST FOCUS, May 2008, at 1, 1, available at http://www.firstfocus.net/Download/HousingandChildrenFINAL.pdf (estimating two million children will be impacted by foreclosures, based on a projection of 2.26 million foreclosures). 13. Dan Immergluck & Geoff Smith, The External Costs of Foreclosure: The Impact of Single-Family Mortgage Foreclosures on Property Values, 17 HOUS. POLY DEBATE 57, 58 (2006); see also MARK DUDA & WILLIAM C. APGAR, MORTGAGE FORECLOSURES IN ATLANTA: PATTERNS AND POLICY ISSUES, at ii (Dec. 15, 2005), available at http://www.nw.org/network/neighborworksProgs/foreclosuresolutions OLD/documents/foreclosure1205.pdf. 14. City-data.com, Chicago, IL (Illinois) Housing and Residents, www.citydata.com/housing/houses-Chicago-Illinois.html (last visited Mar. 24, 2009).

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

570

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

The property-value declines caused by foreclosure hurt local businesses and erode state and local government tax bases.15 Condominium and homeowner associations likewise find their assessment base reduced by foreclosures, leaving the remaining homeowners with higher assessments.16 Foreclosed properties also impose significant direct costs on local governments and foster crime.17 A single foreclosure can cost the city of Chicago over $30,000.18 Moreover, foreclosures have a racially disparate impact because African-Americans invest a higher share of their wealth in their homes19 and are also more likely than financially similar whites to have subprime loans.20 In short, foreclosure is an inefficient outcome that is bad not only for lenders and borrowers, but for society at large. Traditionally, bankruptcy is one of the major mechanisms for resolving financing distress. Bankruptcy creates a legal process through which the market can work out the problems created when parties end up with unmanageable debt burdens. Although the process can be a painful one for all parties involved, bankruptcy allows an orderly forum for creditors to sort out their share of losses and return the deleveraged

15. Laura Johnston, Foreclosure Study Says Vacant Properties Cost Cleveland $35+ Million, BLOG.CLEVELAND.COM, Feb. 19, 2008, http://blog.cleveland.com/ metro/2008/02/foreclosure_study_says_vacant.html; see also GLOBAL INSIGHT, THE MORTGAGE CRISIS: ECONOMIC AND FISCAL IMPLICATIONS FOR METRO AREAS 2 (Nov. 26, 2007), available at http://www.vacantproperties.org/resources/documents/ USCMmortgagereport.pdf. 16. Christine Haughney, Collateral Foreclosure Damage, N.Y. TIMES, May 15, 2008, at C1. 17. WILLIAM C. APGAR & MARK DUDA, COLLATERAL DAMAGE: THE MUNICIPAL IMPACT OF TODAYS MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE BOOM (2005), available at http://www.995hope.org/content/pdf/Apgar_Duda_Study_Short_Version.pdf; Dan Immergluck & Geoff Smith, The Impact of Single-Family Mortgage Foreclosures on Neighborhood Crime, 21 HOUS. STUD. 851, 85154 (2006). 18. APGAR & DUDA, supra note 17, at 4. 19. MELVIN L. OLIVER & THOMAS M. SHAPIRO, BLACK WEALTH/WHITE WEALTH: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON RACIAL INEQUALITY 66 (2006) (noting that housing equity accounted for 62.5 percent of all black assets in 1988, but only 43.3 percent of white assets, even though black homeownership rates were 43 percent and white homeownership rates were 65 percent); see also Brian K. Bucks et al., Recent Changes only a $35,000 difference in median home equity between whites and nonwhites/Hispanics in 2004, there was a $115,900 difference in median net worth and a $33,700 difference in median financial assets; this suggests that for minority homeowners, wealth is disproportionately invested in the home); Kai Wright, The Subprime Swindle, NATION, July 14, 2008, at 11, 1112. 20. Mary Kane, Race and the Housing Crisis, WASH. INDEP., July 25, 2008; Bob Tedeschi, Subprime Loans Wide Reach, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 3, 2008.

in U.S. Family Finances: Evidence from the 2001 and 2004 Survey of Consumer Finances, FED. RES. BULL., at A1, A8, A12, A23 (2006) (noting that while there was

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

571

debtor to productivity; a debtor hopelessly mired in debt has little incentive to be economically productive because all of the gain will go to creditors. Moreover, the existence of the bankruptcy system provides a baseline against which consensual debt restructurings can occur. Thus, for over a century bankruptcy has been the social safety net for the middle class, joined later by Social Security and unemployment benefits. The bankruptcy system, however, is incapable of handling the current home-foreclosure crisis because of the special protection it gives to most residential-mortgage claims. While debtors may generally modify all types of debts in bankruptcyreducing interest rates, stretching out loan tenors, changing amortization schedules, and limiting secured claims to the value of collateralthe Bankruptcy Code forbids any modification of mortgage loans secured solely by the debtors principal residence.21 Defaults on such mortgage loans must be cured and the loans then paid off according to their original terms, including all fees that have been levied since default, or else the bankruptcy stay on collection actions will be lifted, permitting the

21. 11 U.S.C. 1322(b)(2) (2006); cf. id. 1123(b)(5) (parallel residential mortgage antimodification provision for Chapter 11). Section 1123(b)(5) provides that a plan of reorganization may modify the rights of holders of secured claims, other than a claim secured only by a security interest in real property that is the debtors principal residence. Id. 1123(b)(5). Since 2005, section 101(13A) of the Bankruptcy Code has defined debtors principal residence as a residential structure, including incidental property, without regard to whether that structure is attached to real property . . . and . . . includes an individual condominium or cooperative unit, a mobile or manufactured home, or trailer. Id. 101(13A). State law, however, still determines what real property is. Modification of a principal residence is even permitted per 11 U.S.C. 1322(c)(2) in cases where the last payment on the contractual payment schedule is due before the final payment on the plan. Am. Gen. Fin., Inc. v. Paschen (In re Paschen), 296 F.3d 1203 (11th Cir. 2002); First Union Mortgage Corp. v. Eubanks (In re Eubanks), 219 B.R. 468 (B.A.P. 6th Cir. 1998). But see Witt v. United Cos. Lending Corp. (In re Witt), 113 F.3d 508 (4th Cir. 1997) (holding that 11 U.S.C. 1322(c)(2) does not permit bifurcation of claims despite its enactment subsequent to the Supreme Court of the United Statess Nobelman decision). It is unclear whether the antimodification provision prevents an undersecured mortgagee from receiving postpetition interest and fees under 11 U.S.C. 506(b). Compare Campbell v. Countrywide Home Loans, Inc. (In re Campbell), 361 B.R. 831, 850 (Bankr. S.D. Tex. 2007) (noting that section 1322(b)(2) trumps section 506(b)), with Citicorp Mortgage, Inc. v. Hunt, No. 5:92CV56(JAC), 1994 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13146, at *89 (D. Conn. 1994) (noting that section 1322(b)(2) does not vitiate section 506(b)). It would seem, however, that the legal fiction engendered by Nobelman v. American Savings Bank s interpretation of section 1322(b)(2) does not require anything beyond treating a principal-home mortgage as fully secured; it need not be treated as oversecured, and if fully secured to the exact amount, postpetition interest and fees could not accrue. 508 U.S. 324 (1993).

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

572

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

mortgagee to foreclose on the property.22 As a result, if a debtors financial distress stems from a home mortgage, bankruptcy is unable to help the debtor retain her home, and foreclosure will occur. The absence of a bankruptcy-modification option also reduces the incentive for creditors to engage in consensual nonbankruptcy debt restructuring. Because of bankruptcys special treatment of principal residential mortgages, the legal mechanism on which the market depends for sorting through debt problems cannot function properly, and this is exacerbating the impact of the mortgage crisis. The Bankruptcy Codes special protection for home-mortgage lenders reflects a hitherto unexamined economic assumption. The assumption is that preventing modification of home-mortgage loans in bankruptcy limits lenders losses and thereby encourages greater mortgage credit availability and lower mortgage credit costs,23 in turn encouraging the homeownership that has been a major goal of federal economic policy for the past half century.24 As Justice John Paul Stevens noted when the Supreme Court of the United States addressed the Bankruptcy Codes antimodification provision in 1993:

22. See 11 U.S.C. 362(d)(1) (authorizing the lifting of an automatic stay for cause if adequate protection cannot be provided). Bankruptcy allows the homeowner to unwind any acceleration on the loan, however. Id. 1322(c). Therefore, if the homeowners problems stem not from a generally unaffordable mortgage payment, but from a temporary loss of income or unexpected one-time expense, bankruptcy can still provide the homeowner with the breathing space to straighten out her finances, deaccelerate, cure, and reinstate the mortgage. 23. See, e.g., Donald C. Lampe et al., Introduction to the 2008 Annual Survey of Consumer Financial Services Law, 63 BUS. LAW. 561, 568 (2008) (Solutions designed to prevent future problems by reducing the availability of credit to marginal borrowers may (in addition to affecting adversely those future borrowers) worsen the current plight of existing marginal borrowers who need to refinance their homes. Direct relief for troubled borrowers, e.g., a foreclosure moratorium or expanded bankruptcy relief, may have the same effect. To some extent this has already happened. The tightening of mortgage law requirements and regulatory restrictions over the past few years in response to allegations of predatory lending have probably contributed to the dramatic increase in foreclosures by making it more difficult for troubled borrowers to refinance. A significant further tightening of these restraintswe have heard this further tightening referred to as more robust regulationmay worsen the problem and increase the number of consumers facing foreclosure as a result.). 24. See, e.g., Consumer Issues in Bankruptcy: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Economic and Commercial Law of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 102d Cong. 56 57 (1992) (statement of Willard Gourley, Jr., BarclaysAmerican Mortgage Corp., on behalf of the Mortgage Bankers Association of America); Douglas G. Baird, Technology, Information, and Bankruptcy, 2007 U. ILL. L. REV. 305, 307 (2007); J. Peter Byrne & Michael Diamond, Affordable Housing, Land Tenure, and Urban Policy: The Matrix Revealed, 34 FORDHAM URB. L.J. 527, 542 (2007); Kenya Covington & Rodney Harrell, From Renting to Homeownership: Using Tax Incentives to Encourage Homeownership Among Renters, 44 HARV. J. ON LEGIS. 97, 99 (2007).

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

573

At first blush it seems somewhat strange that the Bankruptcy Code should provide less protection to an individuals interest in retaining possession of his or her home than of other assets. The anomaly is, however, explained by the legislative history indicating that favorable treatment of residential mortgagees was intended to encourage the flow of capital into the home lending market.25 According to Justice Stevens, Congress intended to promote mortgage lending by limiting lender losses in bankruptcy. Justice Stevenss assertion has scant support in the legislative history,26 but has

25. Nobelman, 508 U.S. at 332 (Stevens, J., concurring). 26. The legislative history that Justice Stevens relied on in his Nobelman concurrence was roughly outlined in Grubbs v. Houston First American Savings Assn, 730 F.2d 236, 24546 (5th Cir. 1984). The legislative history of 11 U.S.C. 1322(b)(2) is scant. The Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-598, 92 Stat. 2549, was a compromise between House and Senate bills. The House bill, H.R. 8200, permitted modification of all secured claims, while the Senate bill, S.B. 2266, contained a provision barring any modification of claims secured by real estate. Grubbs, 730 F.2d at 245. The bills were reconciled through a series of floor amendments, id. at 246, which resulted in a ban on modification of loans secured solely by the debtors principal residence. There was no discussion on the issue in the Congressional Record. It was, however, raised in Senate hearings, most notably in a dialogue amongst Edward J. Kulik, Senior Vice President, Real Estate Division, Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co.; his counsel, Robert E. OMalley, of Covington & Burling; and Senator Dennis DiConcini (D-Ariz.). The dialogue is worth reproducing because it is virtually the only evidence of congressional intent and is less than overwhelming: MR. KULIK: These provisions may cause residential mortgage lenders to be extraordinarily conservative in making loans in cases where the general financial resources of the individual borrower are not particularly strong. Serious consideration should be given to modifying both bills so that, at the least: One, a mortgage on real property other than investment property may not be modified . . . . SENATOR DICONCINI: If [the cramdown provision was] not change[d], you do not really suggest that savings and loans and mortgage bankers will stop lending money, do you? MR. KULIK: Mr. Chairman, I would have to speak for the life insurance industry. I think we would channel more of our funds into direct placements and bond purchases and stay away from mortgages, particularly where limited partnerships are the borrowers. SENATOR DICONCINI: But not as to individuals? MR. KULIK: Let me ask counsel, but I believe individuals are in the same category as limited partnerships. Counsel tells me it is not as serious for individuals.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

574

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

SENATOR DICONCINI: But notwithstanding, there have been times that savings and loan associations in Arizona have really been anxious to loan money, notwithstanding the present law. That happens to be the case right now. That has not always been the case. So, I wonder what really detrimental effect there is. The last part of your statement left me with the indication that this is so severe that if we do not do something, it will severely strangle the home loan mortgage business. I realize the severity of your problem. Your statement is excellent, but I challenge the fact that it is as severe as you left me with the last closing statement that you made. MR. KULIK: Mr. Chairman, counsel has asked to reply. MR. OMALLEY: Mr. Chairman, would you indulge me to speak to that point? SENATOR DICONCINI: Certainly. MR. OMALLEY: With respect to the savings and loans, in particular, and the future prospects for loans to individuals under the proposed bills, there is really only one basic problem. That is, the provision in both bills that provides for modification of the rights of the secured creditor on residential mortgages, a provision that is not contained in present law. I think the answer to your question is that, of course, savings and loans will continue to make loans to individual homeowners, but they will tend to be, I believe, extraordinarily conservative and more conservative than they are now in the flow of credit. It seems to me they will have to recognize that there is an additional business risk presented by either or both of these two bills if the Congress enacts chapter XIII in the form proposed, thus providing for the possibility of modification of the rights of the secured creditor in the residential mortgage area. I think the answer is that they will be much more conservative than they have been in the past.

Hearings on S. 2266 and H.R. 8200 Before the Subcomm. on Improvements in Judicial Mach. of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 95th Cong. 71415 (1977) (testimony

of Edward J. Kulik, Senior Vice President, Real Estate Division, Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co., accompanied by Robert E. OMalley, Attorney, Covington & Burling). See also Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Improvements of the Judicial Mach. of the S. Comm. on Judiciary, 94th Cong. 12728, 130, 13234, 13738 (1975) (statement of Walter Vaughan, American Bankers Association); id. at 14142, 16768, 17680 (statement of Alvin Wiese, National Consumer Finance Association); id. at 64 (written testimony of Conrad Cyr, a bankruptcy judge in Maine (now a federal appeals court judge)) (arguing that modification of real-property mortgages should be permitted in Chapter 13). Despite Senator DeConcinis apparent incredulity, based on his unfortunately intimate knowledge of the savings and loan industry, this dialogue appears to be the basis for assuming a particular policy basis for the antimodification provision. As Grubbs noted, This limited bar [on modification] was apparently in response to perceptions, or to suggestions advanced in the legislative hearings . . . that, home-

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

575

nonetheless become the dominant explanation for the Bankruptcy Codes mortgage antimodification provision. Underlying the economic assumption embedded in the Bankruptcy Codes antimodification provision is another assumptionthat mortgage markets are sensitive to bankruptcy-modification risk. This Article empirically tests the policy assumption behind the Bankruptcy Codes prohibition on the modification of single-family primary-residence mortgages. It marshals a variety of original empirical evidence from mortgage origination, insurance, and resale markets to show that mortgage markets are indifferent to bankruptcy-modification risk.

mortgagor lenders, performing a valuable social service through their loans, needed special protection against modification thereof . . . . 730 F.2d at 246. The evidence for a deliberate policy preference by Congress is very limited. The relationship of section 1322(b)(2) to pre-1978 bankruptcy law is consistent with either an interpretation of it as an explicit and deliberate policy preference by Congress or a special-interest provision. Section 1322(b)(2) appears, at first blush, to continue pre-1978 bankruptcy law, which functionally forbade any modification of a mortgage. But an examination of the details of pre-1978 law shows that the story is more complex. Chapter XIII of the Bankruptcy Act of 1898 was the predecessor of the modern Chapter 13. (Chapter XIII was enacted as part of the Chandler Act on June 22, 1938. Ch. 575, 52 Stat. 840). In a Chapter XIII wage earners plan, there were no statutory limitations on the ability to modify a secured debt, including a mortgage. 11 U.S.C. 646 (1976) (repealed 1978). However, a wage earners plan that affected a secured debt could not be confirmed without the consent of the affected secured creditor. Id. 1052(1) (repealed in 1978). Therefore, it was impossible to modify a mortgage or any other secured debt without the consent of the impaired creditor. In both the House and Senate versions of the Bankruptcy Reform Act, there was no blanket prohibition on the modification of secured debt. In the House version, all secured debts could be modified, just as in Chapter XIII, H.R. 8200, 95th Cong. 132223 (1978), while the Senate version generally permitted the modification for secured debts, but with an exclusion for mortgages. S. 2266, 95th Cong. 132223 (2d Sess. 1978). In both versions, the impaired secured creditors veto was eliminated. Instead, under the final version of Chapter 13, the plan is confirmable if it meets certain statutory requirements for the treatment of secured debts, regardless of the affected secured creditors consent. This history shows that the mortgage antimodification provision is not a continuation of pre-Code bankruptcy law. Pre-Code law permitted modification, subject to a creditor veto, but that was for all secured debts. 11 U.S.C. 1046, 1052(1) (repealed 1978). The Bankruptcy Code instead permits modification without any creditor veto, but carves out one particular class of debts that cannot be modified under a plan, regardless of creditor consent. 11 U.S.C. 1322(b)(2) (2006). Had Congress wished to continue pre-Code law just for mortgages, it could have retained a veto for mortgage creditors. It did not. The history of the antimodification provision and the change from the 1898 Acts veto to the Codes prohibition indicates that section 1322(b)(2) is actually something new, not a continuation of prior practice. While Grubbs assumes otherwise, there is no conclusive evidence in the legislative history that section 1322(b)(2) was intended to lower the cost of mortgage credit or increase its availability. At best, we can say that it was the result of a legislative compromise that gave a subset of mortgage creditors a more favorable position relative to other creditors than they had under the 1898 Act.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

576

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

The Article explains this indifference by reference to data on the relative losses lenders incur in modification and foreclosure, and argues that as long as lenders face larger losses in foreclosure than modification, the mortgage market will not price and ration credit based on bankruptcy-modification risk. Accordingly, this Article argues that the Bankruptcy Code should be amended to permit debtors to modify all mortgages. Such an amendment would provide the most effective, fair, immediate, and tax-payer-cost-free tool for resolving the homemortgage crisis. In a perfectly functioning market without agency and transaction costs, lenders would be engaged in large-scale modification of defaulted or distressed mortgage loans, as the lenders would prefer a smaller loss from modification than a larger loss from foreclosure. Voluntary modification, however, has not been happening on a large scale27 for a variety of reasons,28 most notably contractual impediments,29 agency costs, practical impediments, and other transaction costs.30 If all distressed mortgages could be modified in bankruptcy, it would provide a method for bypassing the various contractual, agency, and other transactional inefficiencies. Permitting bankruptcy modification would give homeowners the option to force a workout of the mortgage, subject to the limitations provided by the Bankruptcy Code. Moreover, the possibility of a bankruptcy modification would encourage voluntary modifications, as mortgage lenders would prefer to exercise more control over the shape of the modification. An involuntary public system of mortgage modification would actually help foster voluntary, private solutions to the mortgage crisis. Unlike programs for government refinancing or insurance of distressed mortgages, the bankruptcy system is immediately available to resolve the mortgage crisis. Government refinancing or insurance plans would take months to implement, during which time foreclosures would continue. In contrast, bankruptcy courts are experienced, up-and27. See, e.g., COMPTROLLER OF THE CURRENCY, OCC MORTGAGE METRICS REPORT: ANALYSIS AND DISCLOSURE OF NATIONAL BANK MORTGAGE LOAN DATA 1, 8 (2008), available at http://www.occ.treas.gov/ftp/release/2008-65b.pdf; see also infra Charts 6 and 7. 28. See generally Kurt Eggert, Limiting Abuse and Opportunism by Mortgage Servicers, 15 HOUS. POLY DEBATE 753 (2004). 29. See generally Anna Gelpern & Adam J. Levitin, Rewriting Frankenstein Contracts: The Workout Prohibition in Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities, 82 S. CAL. L. REV. (forthcoming 2009), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/ papers.cfm?absabstr_id=1323546. See generally CONG. OVERSIGHT PANEL, THE FORECLOSURE CRISIS: 30. WORKING TOWARD A SOLUTION 3748 (2009) (discussing reasons for failure of private modification efforts).

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

577

running, and currently overstaffed relative to historic caseloads.31 Moreover, the bankruptcy automatic stay would immediately halt any foreclosure action in process upon a homeowners filing of a bankruptcy petition.32 And, unlike government guarantees or refinancing, bankruptcy modification of all mortgages would not involve the public fisc. Bankruptcy modification would also avoid the moral hazard for lenders and borrowers of a bailout. Lenders would incur costs for having made poor lending decisions through limited recoveries. Borrowers would face the shame of filing, their finances becoming a matter of public record, the requirement of living for three to five years on a court-supervised budget in which all disposable income goes to creditors, a damaged credit rating, and the inability to file for bankruptcy for a number of years. Bankruptcy modification also provides an excellent device for sorting out types of mortgage debtors. It can correct the two distinct mortgage problems in the current crisispayment-reset shock from resetting adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs), and negative equity from rapidly depreciating home priceswhile preventing speculators and vacation-home purchasers from enjoying the benefits of modification. And, by providing an efficient and fair system for restructuring debts and allocating losses, bankruptcy will help stabilize the housing market. Making bankruptcy a forum for distressed homeowners to restructure their mortgage debts is both the most moderate and the best method for resolving the foreclosure crisis and stabilizing mortgage markets. Permitting modification of all mortgages in bankruptcy would thus create a low-cost, effective, fair, and immediately available method for resolving much of the current foreclosure crisis without imposing costs on the public fisc or creating a moral hazard for borrowers or lenders.

31 See Michelle J. White, Bankruptcy: Past Puzzles, Recent Reforms, and the Mortgage Crisis 18 (Natl Bureau Econ. Research, Working Paper No. 14549, 2008), available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w14549. In 2005, there were 2,078,415 total bankruptcy filings, the highest level on record. USCourts.gov, Bankruptcy Statistics, http://www.uscourts.gov/bnkrpctystats/statistics.htm#june (last visited Mar. 24, 2009). Most of these filings came in a spike before the effective date of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (BAPCPA), Pub. L. No. 109-8, 119 Stat. 23. BAPCPA added twenty-eight new bankruptcy judgeships to the existing 296. Id. 1223. In 2005, the courts were able to handle a significant increase in case filings with fewer judges. The increase in the number of bankruptcy judges means that the courts are better equipped today to handle another surge in filings. 32. 11 U.S.C. 362(a).

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

578

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

This Article proceeds in four Parts. Part I reviews the state of the law on mortgage modification in bankruptcy and the structure and cast of characters in the mortgage market. Part II tests the economic assumption behind the Bankruptcy Codes prohibition on single-family, primary-residence mortgage modification in two ways. First, it examines whether current mortgage-market pricing from the origination market, the secondary market, and the private-mortgage-insurance (PMI) market reflects the risk of modification in bankruptcy that attaches to multifamily properties, vacation homes, and investor properties, but not single-family, owner-occupied principal residences. Second, Part II examines historical mortgage and bankruptcy-filing data from a period when strip-down, a particularly significant type of modification, was permitted in approximately half of the federal judicial districts. Taken together, the current market pricing and the historical data indicate that mortgage markets are largely indifferent to bankruptcy-modification outcomes. The current market data suggest almost complete indifference, whereas the historical data show some sensitivity, particularly for higher-price and higher-loan-to-value-ratio (i.e., riskier) borrowers. Part II includes a significant amount of technical, detailed mortgage-rate analysis that provides important evidence for the Articles argument, but which may not be of interest to all readers. Readers who are not concerned with the technical analysis should skip to Part III. Part III addresses why mortgage markets are so indifferent to bankruptcy-modification risk. Using data from Chapter 13 bankruptcy filings, it examines the impact of permitting strip-down on mortgage lenders and shows that its impact is usually far less than the lenders would lose in foreclosure. Because lenders would generally fare better in bankruptcy than in foreclosure, they do not price adversely to a bankruptcy-modification option. Part IV considers the policy implications of market indifference to bankruptcy-modification risk and compares bankruptcy modification to other proposed solutions to the mortgage crisis, establishing that bankruptcy modification offers unparalleled advantages over other potential solutions. This Article concludes by positing a new theory of the relationship of consumer finance and bankruptcy law, namely that changes in the structure of the lending market mean that bankruptcy law has little effect on consumer credit, so consumer-bankruptcy policy should not be guided by concerns over credit constriction. Two appendices contain illustrative data and a debunking of the Mortgage Bankers Associations claims about the likely impact of bankruptcy modification on mortgage interest rates and credit availability.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

I. THE STRUCTURE OF THE MORTGAGE MARKET

579

A. Treatment of Mortgages in Bankruptcy

There are two main types of consumer bankruptcy, Chapter 7 liquidations and Chapter 13 repayment plans.33 In Chapter 7, the debtor surrenders all nonexempt assets for distribution to creditors.34 In most circumstances, this means that a Chapter 7 debtor will not be able to retain her home. In Chapter 13, in contrast, the debtor retains all of her property, but must devote all disposable personal income for the next three or five years to repaying creditors under a court-supervised repayment plan and budget.35 Chapter 13, then, is the type of bankruptcy generally suited for a debtor seeking to retain major property, such as a residence.36 Debtors in Chapter 13 repayment-plan bankruptcies are able to modify almost all types of debts. This means they can change interest rates, amortization, and terms of loans.37 They can also strip-down debts secured by collateral to the value of the collateral.38 Strip-down bifurcates an undersecured 39 lenders claim into a secured claim for the value of the collateral and a general unsecured claim for the deficiency. In Chapter 13, a creditor is guaranteed to receive the value of a secured

33. Consumers are also eligible for Chapter 11, but few who are eligible for Chapter 13, see id. 109(e), use Chapter 11 because of greater creditor control in Chapter 11 through creditor voting rights on plans of reorganization. 34. Id. 522(b), 541. 35. Id. 1325(b). 36. A debtor may enter into a court-approved reaffirmation agreement with a creditor and retain nonexempt property in exchange for continuing to make payments to the lender. Id. 524(c). Alternatively, a debtor may redeem collateral in bankruptcy by paying the lender the value of the property. Id. 722; cf. UCC 9-623 (2008) (illustrating that redemption at state law requires paying the full amount outstanding on the loan plus reasonable lender expenses). 37. 11 U.S.C. 1322(b)(2). 38. See id. 506. Strip-down is synonymous with lien-stripping and cramdown. Because cramdown has a distinct meaning in the context of Chapter 11 reorganizationsthe confirmation of a plan of reorganization absent approval of all impaired classes of creditors and equity-holders under the provisions of 11 U.S.C. 1129(b)I use the term strip-down. 39. A loan is undersecured if the amount owned on the loan is more than the value of the collateral securing the loan. If there is no collateral securing the loan, the loan is unsecured. Undersecured lenders and loans are also referred to as upsidedown or underwater. The homeowner in such a situation has negative equity. If there are multiple mortgages on the property, it is possible for the homeowner to have negative equity even though the senior mortgage is still oversecured.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

580

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

claim.40 In contrast, general unsecured claims are guaranteed only as much as would be paid out in a Chapter 7 liquidation, which is often mere cents on the dollar or nothing at all.41 Therefore, strip-down can function like a reduction in the principal amount owed on a debt. Strip-down is thus the most significant type of modification because it affects the treatment of the principal amount of the creditors claim, not just the interest. Because of compound interest, a strip-down of X percent of the principal will have a larger impact on the total return than a modification of X percent of the interest rate. Moreover, because most residential mortgages are prepaid (typically through refinancing) in their first seven years,42 an adjustment to principal is more significant than an adjustment to interest rates. A reduction in secured principal has an immediate impact on the loan, whereas a reduction in the interest rate is spread out for the full term of the loan, so if the loan is prepaid, the reduction in interest income is curtailed.

40. Id. 1325(a)(5)(B). Section 1325(a)(5) only applies to allowed secured claims provided for by the plan. Therefore, it is possible for a debtor to deal with a secured claim outside of a plan and not subject to 1325(a)(5)s requirement. It is also important to note that courts have split regarding whether section 1325(a)(5) requires that a debt be paid off under a plan. For non-principal-residence mortgages, debtors will sometimes propose to modify the mortgage through strip-down and then maintain payments on it pursuant to the original term of the loan (reamortized or not). Compare Enewally v. Wash. Mut. Bank (In re Enewally), 368 F.3d 1165, 1172 (9th Cir. 2004) (holding that a modified mortgage on rental property must be paid off during a plan), with In re McGregor, 172 B.R. 718, 721 (Bankr. D. Mass. 1994) (suggesting that a debtor might amend a plan to provide for payments on stripped-down principal at the original contract interest rate in the amount called for by the mortgage contract until the total principal payments equaled the allowed amount of the secured claim). An argument that courts do not appear to have considered is that section 1325(a)(5)(B)(ii) merely requires distribution of value equal to the allowed amount of a secured claim, and that this value could be in the form of a note with a term longer than the duration of the plan. As Justice Thomas observed in his plurality concurrence in Till v. SCS Credit Corporation, 541 U.S. 465 (2004), an auto-loanstrip-down case, nothing in 1325 suggests that property is limited to cash. Rather, property can be cash, notes, stock, personal property or real property; in short, anything of value. Id. at 488 (Thomas, J., concurring). The payment of a secured debt with a new note is frequently done in Chapter 11 under the parallel provision for distributions to secured creditors, section 1129(a)(7)(A)(ii). Perhaps the best evidence that cash is not required is that the Bankruptcy Code specifically calls for cash distributions in other circumstances, such as requiring cash payments for administrative expense claims. See 11 U.S.C. 1129(a)(9), 1322(a)(2). If cash payment is not required, then distributions could be made during the plan that would essentially transform the old debt into a new one with a duration longer than the plan. 41. Id. 1325(a)(4). See Wesley Phoa, A Practical Guide to Relative Value for Mortgages, in 42. MANAGING FIXED INCOME PORTFOLIOS 357, 363 (Frank J. Fabozzi ed., 1997).

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

581

Chapter 13 provides debtors with a very broad ability to restructure their debts. There is a significant limitation, however, for certain home mortgages. Section 1322(b)(2) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that a Chapter 13 repayment plan may modify the rights of holders of secured claims, other than a claim secured only by a security interest in real property that is the debtors principal residence.43 Section 1322(b)(2) thus prevents modification only of mortgages secured solely by real property that is the debtors principal residence.44 Under current law, debtors can modify mortgages on vacation homes, investor properties, and multifamily residences in which the owner occupies a unit.45 Debtors can also currently modify wholly

43. 11 U.S.C. 1322(b)(2). For the history of this provision, see Veryl Victoria Miles, The Bifurcation of Undersecured Residential Mortgages Under 1322(b)(2) of the Bankruptcy Code: The Final Resolution, 67 AM. BANKR. L.J. 207 (1993). 44. 11 U.S.C. 1322(b)(2). Sections 1322(b)(2) and 1325(a)(5) place limitations on the modification of all mortgages. It is important to note that the protections given mortgage holders depend on owner-occupancy status, so mortgage holders protections are dependent upon debtor cooperation, a factor upon which mortgage holders cannot justifiably rely. 45. See, e.g., Scarborough v. Chase Manhattan Mortgage Corp. (In re Scarborough), 461 F.3d 406, 408, 41213 (3d Cir. 2006) (permitting strip-down on a two-unit property in which the debtor resided); Chase Manhattan Mortgage Corp. v. Thompson (In re Thompson), 77 Fed. Appx. 57, 58 (2d Cir. 2003) (permitting stripdown on a three-unit property in which the debtor resided); Lomas Mortgage, Inc. v. Louis, 82 F.3d 1, 7 (1st Cir. 1996) (permitting strip-down on a three-unit property in which the debtor resided); First Nationwide Mortgage Corp. v. Kinney (In re Kinney), No. 3:98CV1753(CFD), 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22313, *1113 (D. Conn. Apr. 12, 2000) (permitting modification of a two-unit property in which the debtor resided); In re Stivender, 301 B.R. 498, 500 n.2 (Bankr. S.D. Ohio 2003) (permitting bifurcation on a two-unit property containing the debtors residence); Enewally v. Wash. Mut. Bank (In re Enewally), 276 B.R. 643, 652 (Bankr. C.D. Cal. 2002) (holding a mortgage on a rental property that is not the debtors residence may be modified); In re Kimbell, 247 B.R. 35, 38 (Bankr. W.D.N.Y 2000) (permitting bifurcation on a twounit property containing the debtors residence); Ford Consumer Fin. Co. v. Maddaloni (In re Maddaloni), 225 B.R. 277, 278 (D. Conn. 1998) (permitting bifurcation on a two-unit property containing the debtors residence); In re Del Valle, 186 B.R. 347, 34850 (Bankr. D. Conn. 1995) (permitting modification of a two-unit property, where the debtor lived in one unit and rented the other); Adebanjo v. Dime Sav. Bank, FSB (In re Adebanjo), 165 B.R. 98, 100 (Bankr. D. Conn. 1994) (permitting bifurcation on a three-unit property containing the debtors residence); In re McGregor, 172 B.R. 718, 721 (Bankr. D. Mass. 1994) (permitting modification of a mortgage of a four-unit apartment building in which the debtor resided); Zablonski v. Sears Mortgage Corp. (In re Zablonski), 153 B.R. 604, 606 (Bankr. D. Mass. 1993) (holding that a mortgage encumbering a two-family home was not protected from modification); In re McVay, 150 B.R. 254, 25657 (Bankr. D. Or. 1993) (failing to protect a mortgage encumbering a bed and breakfast, which was the debtors principal residence but which had inherent income producing power, from modification).

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

582

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

unsecured second mortgages on their principal residences,46 as well as loans secured by yachts, aircraft, jewelry, household appliances, furniture, vehicles, or any other type of personalty.47 The Bankruptcy Code, however, forbids the modification of mortgage loans secured solely by the debtors principal residence.48 Such mortgage loans must be cured and then paid off according to their original terms, including all fees that have been levied since default, or else the bankruptcy automatic stay will be lifted, permitting the mortgagee to foreclose on the property.49 As a result, if a debtors financial distress stems from an unaffordable home mortgage, bankruptcy is unable to help the debtor retain her home, and foreclosure will occur.

B. Structure of the Modern Mortgage Market

Mortgage markets reaction to bankruptcy-modification risk is shaped by the structure of modern mortgage markets. Traditionally, mortgage lenders looked like the Bailey Building & Loan Association of Bedford Falls (Bailey) in Frank Capras classic Christmas film, Its a Wonderful Life.50 Bailey would make mortgage loans to borrowers in the Bedford Falls community and keep the loans on its books as

46. Every federal circuit court of appeals addressing the issue has held that modification, including strip-down, of wholly unsecured second mortgages on principal residences is permitted. See, e.g., Lane v. W. Interstate Bancorp (In re Lane), 280 F.3d 663, 669 (6th Cir. 2002); Zimmer v. PSB Lending Corp. (In re Zimmer), 313 F.3d 1220, 1227 (9th Cir. 2002); Pond v. Farm Specialist Realty (In re Pond), 252 F.3d 122, 126 (2d Cir. 2001); Bartee v. Tara Colony Homeowners Assn (In re Bartee), 212 F.3d 277, 288 (5th Cir. 2000); McDonald v. Master Fin., Inc. (In re McDonald), 205 F.3d 606, 608 (3d Cir. 2000); Tanner v. FirstPlus Fin., Inc. (In re Tanner), 217 F.3d 1357, 1360 (11th Cir. 2000); Lam v. Investors Thrift (In re Lam), 211 B.R. 36, 41 (B.A.P. 9th Cir. 1997). These are known as the Son of Strip-down cases. 47. 11 U.S.C. 1322(b)(2). Until 2005, loans secured by all vehicles could be stripped down. Since October 17, 2005, purchase money loans secured by motor vehicles may not be stripped down in their first two-and-a-half years, and other purchase money secured loans may not be stripped down in their first year. Id. 1325(a). 48. See supra note 21. 49. See 11 U.S.C. 362(d). Bankruptcy allows the homeowner to unwind any acceleration on the loan, however. Id. 1322(c). Therefore, if the homeowners problems stem not from a generally unaffordable mortgage payment, but from a temporary loss of income or unexpected one-time expense, bankruptcy can still provide the homeowner with the breathing space to straighten out her finances, deaccelerate, and reinstate the mortgage. 50. RKO Radio Pictures 1946.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

583

assets.51 Bailey had a portfolio of Bedford Falls mortgages and longstanding banking relationships with its borrowers.52 Bailey faced two key problems with its business model. First, the mortgage loans held by Bailey were largely illiquid, long-term assets, so Bailey could not sell them to improve its short-term cash flow.53 Second, due to interstate-banking restrictions, all the loans were made in the Bedford Falls area, which meant they were not diversified, making Bailey heavily exposed to the overall economic conditions of Bedford Falls.54 As a result, Bailey had to be careful about its lending, but having community-based relationships with its borrowers gave it additional information for sound loan underwriting.55 Over the past quarter century or so, the mortgage industrys traditional relational-portfolio-lending model has been replaced with an originate-to-distribute (OTD) model designed to increase liquidity and portfolio diversification in mortgage lending.56 The OTD mortgage market involves a cast of several players: originators; private mortgage insurers; and secondary-market securitizers, including governmentsponsored entities (GSEs), mortgage-pool insurers, mortgage-backed security investors, and servicers. First, there are the financial institutions that advance (or, in mortgage-industry parlance, originate) the mortgage loan to the homeowner, sometimes directly, and sometimes through mortgage brokers. These institutions include commercial banks, savings banks, credit unions, finance companies, and mortgage banks. If the loan-tovalue (LTV) ratio on the mortgage exceeds 80 percent, mortgage insurance will generally be required to make the loan marketable on the secondary market.57 Usually the mortgage insurance is purchased by the

51. Id. Before 1994, there was no interstate branch banking, so most lending was local. See Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994, Pub. L. No. 103-328, 109(c), 108 Stat. 2338, 2338 (codified at 12 U.S.C. 1835(a)). 52. ITS A WONDERFUL LIFE (RKO Radio Pictures 1946). 53. Id. Id. 54. See id. 55. 56. See infra Chart 2. 57. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored entities that dominate the secondary mortgage market, will not purchase standard mortgages with LTVs of more than 80 percent without mortgage-insurance coverage. FANNIE MAE, SINGLE FAMILY 2007 SELLING GUIDE, at pt. V, 101.01 (2007), available at https://www.efanniemae.com/sf/guides/ssg (under Online Access click Access AllRegs and choose the appropriate part and section); FREDDIE MAC, SINGLE-FAMILY SELLER/SERVICER GUIDE, at 27.1, (2009), available at http:// www.freddiemac.com/sell/guide/# (under Access the Guide click AllRegs and choose the appropriate chapter).

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

584

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

homeowner, with the mortgagee as the payee, but it can also be lender purchased.

100% Market Share ($ Outstanding) 80% 60% 40% 20% 0%

1 Q 20 08

80

84

88

60

64

68

72

76

92

52

56

96

00

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

19

20

Private Label MBS Pools GSEs Savings Institutions and Credit Unions Household Sector

Agency & GSE MBS Pools Commercial Banks Insurance Companies Other

Chart 2: Holders of Residential One-to-Four-Family Mortgages by Entity Type58 Sometimes originators hold the mortgage loans on their own books, but often (indeed, almost always, in the case of mortgage banks) they sell them into the secondary market. Sometimes this is done through a direct securitization, in which the originator sells a pool of mortgage loans to a specially created entity (special purpose vehicle or SPV), typically a trust (a securitization trust).59 The SPV pays for the mortgage loans by selling securities, secured by the pooled mortgages, to capital-market investors.60 These securities are the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) because they are collateralized or backed by the mortgages in the pool. Often, however, the originator does not securitize the loans directly. Instead, the originator sells the loans to either a GSE like Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac or to a private securitization conduit, such

58. See Fed. Reserve Bank, Statistical Release, No. Z.1, Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States, at tbl.L.217 (Dec. 11, 2008), available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/accessible/1217.htm. 59. VINOD KOTHARI, SECURITIZATION: THE FINANCIAL INSTRUMENT OF THE FUTURE 11 (2006). Id. 60.

20

04

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

585

as an investment bank.61 Sometimes these entities retain the mortgages in their own portfolios, but they generally pool mortgages originated by many different originators and undertake a multiconduit securitization. Sometimes MBS are themselves pooled and securities are issued against a pool of MBS, in what is called a collateralized debt obligation (CDO).62 It is estimated that 75 percent of outstanding first-lien residential mortgages are held by securitization trusts, and that twothirds are in GSE MBS.63 The MBS issued by the SPVs are typically divided into slices or tranches of various risk, based on senior or subordinated status.64 The price of the various MBS tranches is largely determined by the ratings given to them by rating agencies like Moodys, Standard and Poors, and Fitch Ratings.65 The credit ratings of various MBS tranches are often enhanced through myriad credit-enhancement mechanisms, such as overcollateralization or pool-levelstop-loss bond insurance.66 Although the securitizer does not carry the mortgages it has sold to the SPV on its books, it frequently keeps a relationship with the mortgages it has sold by entering into a pooling and servicing agreement (PSA) with the SPV.67 Because the SPV exists only on paper, it needs an agent to manage and collect (or service) the loans it owns.68 The PSA is the contract that creates the principal-agent relationship between the SPV and the servicer. The originator will thus service the loans even though it does not hold them on its books, creating a potential moral hazard as the servicer does not internalize the full costs and benefits of its actions. A homeowners mortgage may thus be transferred several times during its lifetime, even as the servicer remains the same (or the servicer may change while the ultimate ownership of the mortgage remains constant).

61. Id. at 32829. Id. at 41314. 62. 63. See CREDIT SUISSE EQUITY RESEARCH, supra note 9, at 28. 64. KOTHARI, supra note 59, at 57, 211. 65. Id. at 208. Id. at 21130 (discussing various credit-enhancement techniques). 66. 67. Id. at 209. Typically securitization originators retain the last-out equity tranche of the trust, which allows them to retain any excess spread over the trusts payout. Id. at 289. Id. at 209. 68.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

586

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

II. BANKRUPTCY-MODIFICATION RISK AS REFLECTED IN MORTGAGE-MARKET PRICING

Because only certain types of residential mortgages are subject to the Bankruptcy Codes antimodification provision,69 it is possible to examine different types of mortgage-market pricing to see if they reflect differences in bankruptcy-modification risk. One would expect that if the market were sensitive to bankruptcy modification, there would be a risk premium for mortgages on the types of property that can currently be modified in bankruptcymortgages on vacation homes, multifamily homes, and investment propertiesand that this premium would not exist for single-family, owner-occupied, principalresidence mortgages, which cannot be modified. To test this hypothesis, I examined three different pricing measures in mortgage markets: effective mortgage interest rates (annual percentage rates or APRs), PMI rates, and secondary-mortgage-market pricing from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In each market I examined rate variation by property type in order to isolate the expected risk premium for bankruptcy-modification risk on non-single-family, owneroccupied properties. Astonishingly, all three measures indicate that mortgage markets are indifferent to bankruptcy-modification risk, at least in terms of pricing.70

A. Mortgage-Interest-Rate Variation by Property Type

1. EXPERIMENT DESIGN Using online rate-quote generators, I pricing on six types of properties to see variations in bankruptcy-modification risk:71 family, principal residences; single-family tested current mortgage if the pricing reflected owner-occupied, singlesecond homes; owner-

69. See supra text accompanying notes 4346. 70. It is possible that there is simply less available credit for modifiable properties. I was unable to test this possibility, however. 71. The reliability of online quotes was confirmed in interviews with veteran mortgage brokers. E.g., Telephone interview with Dom Sutera, The Sutera Group (Jan. 23, 2008). In response to my congressional testimony based on a draft of this Article, David M. Kittle, the President of the Mortgage Bankers Association, declared that online rate quotes were unreliable. Helping Families Save Their Homes: The Role of Bankruptcy Law, Hearing Before the S. Judiciary Comm., 110th Cong. (1998) (testimony of David Kittle). Mr. Kittles surprising admission of mortgage industry bait-and-switch tactics aside, the rate-quote generators results are consistent with other, more reliable data sources, see infra Sections II.B., C, as well as with quotes produced by the Mortgage Bankers Association in Mr. Kittles own testimony.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

587

occupied, two-family residences; owner-occupied, three-family residences; owner-occupied, four-family residences; and investor properties. I obtained the quotes from four major mortgage lenders: eLoan, IndyMac, Chase, and Wachovia.72 These lenders were selected because their online quote generators did not require disclosure of personal information. The quotes were generated between January 17, 2008 and January 27, 2008.73 Using the online quote generators, I tested 530 mortgage rate quotes from eleven states. The quotes were divided into two subsamples. First I took a standardized sampling of 288 quotes in three states: California, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. I chose Massachusetts and Pennsylvania because of the clarity of the law in those states, which are located in the jurisdictions of the United States Courts of Appeals for the First and Third Circuits, respectively. There is unambiguous circuit-level law in both the First and Third Circuits permitting the strip-down of mortgages on all multiunit residences.74 I included California both because it is the largest single state mortgage market and because it has been hit particularly hard by the mortgage crisis.75 For this three-state sample, I obtained 288 quotes for 30-year fixed-rate, first-lien purchase money mortgages, the most common traditional-mortgage product. I tested assuming a LTV ratio of 80 percent, representing a 20 percent down payment. Half of the quotes obtained were for loan amounts within the GSE-conforming limits, and half were for nonconforming jumbos.76 The conforming quotes were

72. Chases online rate-quote generators can be found at http://mortgage.cha se.com/pages/purchase/crq_p_landing.jsp. Since the time I gathered the rate quotes, IndyMac and Wachovia both failed, so their quote generators are no longer available, and eLoan has outsourced its rate quotes to Lending Tree. 73. IndyMac was placed in an FDIC conservatorship on July 11, 2008. Louise Story, Regulators Seize IndyMac After a Run on the Bank, N.Y. TIMES, July 12, 2008, at C5. 74. See, e.g., Scarborough v. Chase Manhattan Mortgage Corp. (In re Scarborough), 461 F.3d 406, 413 (3d Cir. 2006); Lomas Mortgage, Inc. v. Louis, 82 F.3d 1, 7 (1st Cir. 1996). 75. Kevin Yamamura, Schwarzenegger Vetoes Mortgage Broker Restrictions, SACRAMENTO BEE (Cal.), Sept. 26, 2009, at A3 (California is the epicenter of the national foreclosure crisis.) (quoting Paul Leonard, California Office Director, Center for Responsible Lending). 76. Federal law limits the size of loans that GSEs may purchase. 12 U.S.C. 1454(a)(2)(C) (2006). Loans above the conforming limit are known as jumbos. Bob Tedeschi, The Race Is to the Swift, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 10, 2008. The limits are adjusted annually. 12 U.S.C. 1454(a)(2)(C). For 2007, the limit was $417,000. Press Release, Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, 2007 Conforming Loan Limit to Remain at $417,000 (Nov. 28, 2006), available at www.ofheo.gov/media/pdf/ PRConfLoan07.pdf; OFHEO.gov, Supervision & Regulations: Conforming Loan

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

588

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

for loan amounts based on the average mortgage loan amount in the state. The quotes for the jumbos were for loan amounts slightly higher than the conforming limit for a three-family residence.77 For each of the six types of residences, I recorded the quoted interest rate, points, and APR for the lowest APR quotation. For IndyMac and eLoan, I obtained a full set of quotes for each of three different credit scores: 760, 660, and 560, representing prime, Alt-A, and subprime borrowers, respectively.78 For Chase and Wachovia, I was not able to test for specific credit scores and have assumed that the single set of quotes generated are for prime borrowers, based on rate comparisons with IndyMac and eLoan.79 Accordingly, in each state I tested thirty-six quotes for IndyMac and eLoan, and twelve for Chase and Wachovia, for a total of 96 quotes per state and 288 quotes total. Appendix A provides an illustrative example of the data. Appendix A shows the rate quotes generated by IndyMac on January 27, 2008, for mortgages in California within conforming limits at 20 percent and 10 percent down (Tables A1A3 and A4A5, respectively) with variations by credit scores. As a cross-check on the ability to extrapolate from 30-year-fixed, first-lien, purchase-money-mortgage rate quotes in California, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania, I also tested an additional

Limits, http://www.ofheo.gov/Regulations.aspx?Nav=128 (last visited Jan. 27, 2009). In 2007, the limit was temporarily raised for selected metropolitan statistical areas by different amounts. See OFFICE OF FEDERAL HOUSING ENTERPRISE OVERSIGHT, METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS, MICROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS AND RURAL COUNTIES WITH NEW LOAN LIMITS (2008), available at http:// www.ofheo.gov/media/hpi/AREA_LIST_5_2008.pdf. As of July 30, 2008, OFHEO was replaced by the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-289, 1101, 130104, 122 Stat. 2654. 77. By testing just above the conforming limit for three-family residences, all of the four-family-residence quotes ended up being for conforming properties because of the higher conforming loan limit for four-family residences. I tested just above the three-family limit out of concern that the loan amount necessary for a four-family jumbo might be so large as to distort the results for single- and two-family properties. Since there is no difference in legal treatment of three-family and four-family residences, I do not believe that the absence of four-family jumbos from our sampling is significant. 78. There is no standard definition of subprime credit score; cutoffs of 600, 620, or even 650 are commonly used. There is also no standard definition of Alt-A; it can range between 620 to 800+. See Jody Shenn, Subprime Meltdown Snares Borrowers with Better Credit, BLOOMBERG.COM, Mar. 22, 2009, http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&refer=home&sid=a8ilcv.eOx Mc. 79. Chase permits specification of credit by characterization (excellent, good, fair, etc.), but not by score. See Mortgage.chase.com, Check Rates, http://mortgage.chase.com/pages/refinance/crq_r_landing.jsp (last visited Mar. 25, 2009). I used excellent as the assumption.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

589

nonscientific sample of 242 quotes from those three states, as well as from eight additional states: Illinois, Florida, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Ohio, Nevada, and Texas. In this sample I tested at a variety of credit scores, ranging from 540 to 760, a range of LTV ratios from 90 percent to 70 percent, a variety of property values, and other mortgage products such as 15-year-fixed mortgages, 2/1 and 5/1 LIBOR adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs), and interest-only mortgages. 2. EXPERIMENT RESULTS The samplings produced three general rate-quote patterns that did not vary by either state or mortgage product type. First, for all conforming mortgage loans with 20 percent down payments from eLoan, IndyMac, and Wachovia, there was no difference in credit scores between the quotes offered for single-family primary residences, vacation homes, or any multifamily unit in which one unit is owner occupied.80 Interest rates, points, and APRs were identical for these property types, despite the variation in bankruptcy-modification risk. Uniformly, however, investor properties had higher interest rates and points. The rate-spread patterns in the quotes make sense intuitively. Investor properties share the same bankruptcy-modification risk as vacation homes and multifamily residences. Therefore, the rate premium on investor-property mortgages cannot be attributed to bankruptcy-modification risk because there is not also a corresponding rate premium for vacation homes or multifamily homes. Instead, to the extent that investor-property mortgages have a premium over mortgages on single-family, owner-occupied properties, it reflects risks distinct from bankruptcy modification. It is unsurprising that vacation homes have the same rates as single-family principal residences. Vacation homes reputedly have lower default rates than principal residences because typically only well-heeled buyers purchase them. They do not have tenant risks such as vacancy, nonpayment, or damage, and they are typically well maintained because of the pride-of-ownership factor. Arguably neither vacation-home nor investor-property mortgages reflect a premium for bankruptcy modification because neither is likely

80. Chase rate quotes for conforming 20-percent-down mortgages presented a variation on this pattern. Single-family principal residences, vacation homes, and fourfamily residences had identical quotes, but two- and three-family residences were priced around twenty-five basis points higher, and 30-year-fixed quotes were unavailable for investor properties.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

590

WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW

to be modified in bankruptcy. A mortgage-loan modification in bankruptcy can occur only as part of a plan.81 The automatic stay would likely be lifted on an investment property (or vacation home) before a plan could be confirmed. The Bankruptcy Code provides that the automatic stay shall be lifted for cause, including either lack of adequate protection of a secured creditors interest in the propertythat is, payments to compensate the secured creditor for depreciation in its collateral during the bankruptcyor the debtors lack of equity in the property, if the property is not necessary for an effective reorganization.82 Therefore, debtors with positive equity who could not handle mortgage payments would be unlikely to be able to make the adequate-protection payments necessary to prevent the lifting of the stay,83 and debtors with negative equity would find the stay lifted because investment properties and second homes are not essential to their reorganizations.84 Thus, investor-property and vacation-home mortgages do not provide particularly meaningful comparisons to single-family, owneroccupied properties when considering bankruptcy-modification risk because both are unlikely to be modified. In contrast, multifamily residences in which the debtor occupies a unit are essential to a debtors successful reorganization, and therefore present a valid comparison to single-family, owner-occupied properties. Multifamily residences in which the owner resides carry the same tenant risks as investor properties. I do not have default-rate data on multifamily residences, but owner residency likely reduces default risk and ensures reasonable property maintenance. Significantly, for all four lenders, single-family primary residences, which are not modifiable in bankruptcy, were priced the same as both vacation homes and at least one of the multifamily residence types, property types that are modifiable in bankruptcy. The expected rate-premium differential among property types does not exist.85 When I reduced the down payment to 10 percent on conforming mortgages, a slightly different pattern emerged. First, rate quotes were

81. 11 U.S.C. 1321, 1322(b). 82. Id. 362(d). See id. 362(d)(1). 83. 84. See id. 362(d)(2). 85. In theory, the lack of the differential could be explained by the market anticipating bankruptcy-reform legislation, which would impose the same basic modification risk on all properties, even if the risk would actually be less for investor properties and vacation homes because of the greater likelihood that the stay would be lifted on those properties.

LEVITIN - FINAL

4/23/2009 11:40 AM

2009:565

Foreclosure Crisis

591