Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Theories of Motivation

Uploaded by

gangadhar119Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Theories of Motivation

Uploaded by

gangadhar119Copyright:

Available Formats

THEORIES OF MOTIVATION Taylor, Frederick W (1856-1915) An American engineer who invented work study and developed the scientific

c approach to management. Taylor advocated division of labor, specialized tools, piece-rate payments and tighter management control for improving productivity. Taylors management principles had considerable impact in America, the most visible being the mass production system at Ford. While Taylors system began as an attempt to develop the perfect pay-for-performance formula, it quickly came to encompass broader issues of work and control. Taylor realized the need for standardizing work, tools, and maintenance techniques to improve productivity. Standardization, in turn, demanded a level of control over work that had never been attempted before. Taylor began by examining not just how long a particular task took to complete but how long it should take. Taylor used a stopwatch and recorded his observations in a notebook. He broke each job and work process down into discrete parts, studying and timing the movements of men and machines. Taylor realized that while two machinists might be working on entirely different products, such as a railroad tire and an engine part, the elementary steps in the job were the same. The secret of improving productivity was to improve and standardize the elementary steps and apply them to a wide range of tasks. By breaking each job down into its component parts, Taylor determined, how production machinery could be modified and individual operations improved or eliminated. Taylor was eager to learn from the best of the skilled workmen, especially machinists, and was prepared to promote them. But those who were left to operate on the factory floor were stripped of their individual artistry. By deskilling the foremens jobs, no single foreman needed to understand the entire range of supervisory work. Taylor also introduced an elaborate planning department that was responsible for coordinating the work of the foreman, designing work flow and conducting cost-accounting reviews. The main limitation of Taylorism was that it failed to see a factory as a social system. Today, Taylorism has fallen out of fashion. Knowledge workers like to be left free and do not want to be micro managed as Taylorism would advocate. Mayo, Elton and Roethlisberger, Fritz 1: Mayo and Roethlisberger pointed out that, psychological techniques and social interaction held the key to managing the relationships within social systems and to improve employee morale and productivity. Roethlisberger and Mayo insisted that behavior of employees was influenced as much by their role in a work group and their relationship to their colleagues as by the promise of economic gain. They were among the first to draw attention to the power of the informal organization. Mayo traced the root of many problems in the work place to the shift from the skilled trades of the nineteenth century, with their strong community ties, to the rise of unskilled, migrant laborers. Industry had effectively destroyed the selfesteem of skilled tradesmen and was ill equipped to deal with the alienation and disaffection of blue-collar workers, most of whom had been uprooted from their communities. Together Mayo and Roethlisberger conducted the famous Hawthorne experiments to study human motivation. The experiments exposed the inadequacy of the piecework system and challenged the assumption that there was a neat correlation between pay levels and productivity. The experiments also exposed the complex way in which the relationships between supervisors and workers could affect output. In the first set of tests, known as the illustration experiments, workers were divided into two groups a test group in which the workers were submitted to increasing amounts of light and a control group, which worked under a constant light intensity. Contrary to expectations, productivity increased in both groups. The workers seemed to be responding more to the attention they were receiving from management than to any actual change in working conditions. This response of the workers was called the Hawthorne effect. In the last set of investigations, known as the Bank Wiring Observation Room experiments, the room was staffed with 14 workmen, paid according to a group piecework system. The more components they turned out, the more money they made. So it was logical to expect that the most efficient workers would put pressure on the slower workers to maintain

1

Abstracted from the book The essence of Competitive Strategy written by David Faulkner and Cliff Bowman, published by Prentice Hall of India in 2002.

a high level of output. This did not prove to be the case. Instead, the group established an unofficial output norm based on what was considered a fair production quota. Workers who violated the norm by producing either too much or too little, were looked down upon by their coworkers. The informal organization dictated the output of each worker based on its own standards of fairness and the position each worker occupied within the work group. In many smaller organizations, many of the rules of the work place remained implicit, not only the operating rules and standards of performance, but also the rules of communication, that is, to whom one was supposed to go for help. People were bound together by relations that had nothing to do with what they were supposed to be doing. These relations seemed to be important, not only for achieving the objectives of the organization but also for obtaining the cooperation of people. (See Motivation) Maslow, Abraham: Well-known for his needs hierarchy theory of motivation. Unlike many other behavioral scientists of his time, Maslow did not analyze and study mental dysfunction. Instead, he tried to seek out and probe the healthiest minds and best-balanced personalities he could find. Maslow believed in the innate potential of human beings for goodness and recognized the importance of developing the human capacity for compassion, creativity, ethics, love, and spirituality. All people are born with such basic needs as food and shelter, as well as the emotional yearnings for safety, love, and self-esteem. But these needs are only the foundation of a pyramid of higher aspirations. Man yearns for bread when there is no bread. But when there is plenty of bread and the stomach is full, higher needs emerge. And when these in turn are satisfied, new and still higher needs emerge, and so on. Maslow believed altruism resulted when lower order needs had been largely fulfilled, in childhood, leading to the development of a healthy character Theory of Hierarchy of Needs "If we are interested in what actually motivates us and not what has or will, or might motivate us, then a satisfied need is not a motivator." - Abraham Maslow Abraham Maslow proposed a model of motivation that gained a lot of attention, but not complete acceptance. His theory of human personality has become arguably the most influential conceptual basis for employee motivation to be found in modern industry. He argues that individuals are motivated to satisfy a number of different kinds of needs, some of which are more powerful than others i.e. more prepotent than others. (The term prepotency refers to the idea that some needs are felt as being more pressing than others.) Until these most pressing needs are satisfied, other needs have little effect on an individual's behavior. We satisfy the most prepotent needs first and then progress to the less pressing ones. As one need becomes satisfied, and therefore less important to us, other needs loom up and become motivators of our behavior. Maslow represents this prepotency of needs as a hierarchy. The most prepotent needs are at the bottom. Prepotency decreases as one moves upwards.

Self-actualization - reaching your maximum potential, doing you own best thing Esteem - respect from others, self-respect, recognition Belonging - affiliation, acceptance, being part of something Safety - physical safety, psychological security Physiological - hunger, thirst, sex, rest

According to Maslow these physiological needs are the most prepotent of all needs. This means that in the human being who is missing everything in life in an extreme fashion, it is most likely that the major motivation would be the physiological needs rather than any others. A person who is lacking food, safety, love and esteem would probably hunger for food more strongly than anything else".

Once the first level needs are largely satisfied, the next level of needs would be for safety and security - protection from physical harm, disaster, illness and security of income, life-style and relationships. Once this set of needs have become largely satisfied, individuals become concerned with belonging - a sense of being a member in some group or groups, a need for affiliation and a feeling of acceptance by others. When there is a feeling that the individual belongs somewhere, he is motivated by a desire to be held in esteem. Individuals have a strong need to see themselves as worthwhile people. Without this type of self-concept, one sees oneself as drifting, cut off, pointless. In simpler terms, until one level of need is fairly well satisfied, the next higher need does not even emerge - Maslow's theory postulates that the most basic needs must be satisfied before higher needs can be addressed. Self-actualization according to Maslow "A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately happy. What a man can do, he must do. This need we may call self-actualization... It refers to the desire for self-fulfillment, namely the tendency for one to become actualized in what one is potentially. This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming. Much of the dissatisfaction with certain types of job activities might arise from the fact they are perceived, by the people performing them, as demeaning and therefore damaging to their self-concept. When all these needs have been satisfied at least to some extent, people are motivated by a desire to self-actualize, to achieve whatever they define as their maximum potential, to do their thing to the best of their ability. The specific form these needs take will of course vary greatly from person to person. In his model of motivation, Maslow does not mean that individuals experience only one type of need at a time. An individual probably experiences all levels of needs all the time, only to varying degrees. For example, productivity drops prior to lunch as people transfer their thoughts from their jobs to the upcoming meal. After lunch, food is not uppermost in people's minds but perhaps rest is, as a sense of drowsiness sets in. In most organizational settings, individuals juggle their needs for security - They seek answers to questions like - Can I keep this job? With needs for esteem - If I do what is demanded by the job, how will my peers see me, and how will I see myself? Given a situation where management is demanding a certain level of performance, but where group norms are to produce below these levels, all these questions arise. If the individual does not produce to the level demanded by management, he may lose the job (security). But if he conforms to management's norms rather than those of the group, it may ostracize him (belonging) while the individual may see him or herself as a turncoat (esteem) and may have a feeling of having let the side down (self-esteem.) The point is that individuals do not move simply from one level in the hierarchy to another in a straightforward, orderly manner; there is a constant, but ever-changing pull from all levels and types of needs. The order in which Maslow set up the needs does not necessarily reflect their prepotence for every individual. Some people may have such a high need for esteem that they are able to subordinate their needs for safety, or their physiological or belonging needs to these. A war hero has little concern for safety or physical comfort as he seeks glory mindless of the prospect of destruction.

Most importantly, the hierarchical model is the assertion that once a need is satisfied it is no longer a motivator - until it re-emerges. Food is a poor motivator after a meal. If management placed emphasis on needs that have not been satisfied, employees would be more likely to be motivated towards achieving the goals of the organization. Reiterating Joe Kelly's point, Human behavior is primarily directed towards unsatisfied needs. The model also provides for constant growth of the individual. There is no point at which everything has been achieved. Having satisfied the lower needs, he is always striving to do things to the best of his ability, and best is always defined as being slightly better than before. david c mcclelland's motivational needs theory American David Clarence McClelland (1917-98) achieved his doctorate in psychology at Yale in 1941 and became professor at Wesleyan University. He then taught and lectured, including a spell at Harvard from 1956, where with colleagues for twenty years he studied particularly motivation and the achievement need. He began his McBer consultancy in 1963, helping industry assess and train staff, and later taught at Boston University, from 1987 until his death. McClelland is chiefly known for his work on achievement motivation, but his research interests extended to personality and consciousness. David McClelland pioneered workplace motivational thinking, developing achievement-based motivational theory and models, and promoted improvements in employee assessment methods, advocating competency-based assessments and tests, arguing them to be better than traditional IQ and personality-based tests. His ideas have since been widely adopted in many organisations, and relate closely to the theory of Frederick Herzberg. David McClelland is most noted for describing three types of motivational need, which he identified in his 1961 book, The Achieving Society:

achievement motivation (n-ach) authority/power motivation (n-pow) affiliation motivation (n-affil)

david mcclelland's needs-based motivational model These needs are found to varying degrees in all workers and managers, and this mix of motivational needs characterises a person's or manager's style and behaviour, both in terms of being motivated, and in the management and motivation others. the need for achievement (n-ach) The n-ach person is 'achievement motivated' and therefore seeks achievement, attainment of realistic but challenging goals, and advancement in the job. There is a strong need for feedback as to achievement and progress, and a need for a sense of accomplishment. the need for authority and power (n-pow) The n-pow person is 'authority motivated'. This driver produces a need to be influential, effective and to make an impact. There is a strong need to lead and for their ideas to prevail. There is also motivation and need towards increasing personal status and prestige. the need for affiliation (n-affil)

The n-affil person is 'affiliation motivated', and has a need for friendly relationships and is motivated towards interaction with other people. The affiliation driver produces motivation and need to be liked and held in popular regard. These people are team players. McClelland said that most people possess and exhibit a combination of these characteristics. Some people exhibit a strong bias to a particular motivational need, and this motivational or needs 'mix' consequently affects their behaviour and working/managing style. Mcclelland suggested that a strong n-affil 'affiliation-motivation' undermines a manager's objectivity, because of their need to be liked, and that this affects a manager's decision-making capability. A strong n-pow 'authority-motivation' will produce a determined work ethic and commitment to the organisation, and while n-pow people are attracted to the leadership role, they may not possess the required flexibility and people-centred skills. McClelland argues that n-ach people with strong 'achievement motivation' make the best leaders, although there can be a tendency to demand too much of their staff in the belief that they are all similarly and highly achievement-focused and results driven, which of course most people are not. McClelland's particular fascination was for achievement motivation, and this laboratory experiment illustrates one aspect of his theory about the affect of achievement on people's motivation. McClelland asserted via this experiment that while most people do not possess a strong achievement-based motivation, those who do, display a consistent behaviour in setting goals: Volunteers were asked to throw rings over pegs rather like the fairground game; no distance was stipulated, and most people seemed to throw from arbitrary, random distances, sometimes close, sometimes farther away. However a small group of volunteers, whom McClelland suggested were strongly achievement-motivated, took some care to measure and test distances to produce an ideal challenge - not too easy, and not impossible. Interestingly a parallel exists in biology, known as the 'overload principle', which is commonly applied to fitness and exercising, ie., in order to develop fitness and/or strength the exercise must be sufficiently demanding to increase existing levels, but not so demanding as to cause damage or strain. McClelland identified the same need for a 'balanced challenge' in the approach of achievement-motivated people. McClelland contrasted achievement-motivated people with gamblers, and dispelled a common pre-conception that n-ach 'achievement-motivated' people are big risk takers. On the contrary - typically, achievement-motivated individuals set goals which they can influence with their effort and ability, and as such the goal is considered to be achievable. This determined resultsdriven approach is almost invariably present in the character make-up of all successful business people and entrepreneurs. McClelland suggested other characteristics and attitudes of achievement-motivated people:

achievement is more important than material or financial reward.

achieving the aim or task gives greater personal satisfaction than receiving praise or recognition. financial reward is regarded as a measurement of success, not an end in itself. security is not prime motivator, nor is status.

feedback is essential, because it enables measurement of success, not for reasons of praise or recognition (the implication here is that feedback must be reliable, quantifiable and factual).

achievement-motivated people constantly seek improvements and ways of doing things better. achievement-motivated people will logically favour jobs and responsibilities that naturally satisfy their needs, ie offer flexibility and opportunity to set and achieve goals, eg., sales and business management, and entrepreneurial roles.

McClelland firmly believed that achievement-motivated people are generally the ones who make things happen and get results, and that this extends to getting results through the organisation of other people and resources, although as stated earlier, they often demand too much of their staff because they prioritise achieving the goal above the many varied interests and needs of their people.

The expectancy theory of motivation is suggested by Victor Vroom. Unlike Maslow and Herzberg, Vroom does not concentrate on needs, but rather focuses on outcomes.

Whereas Maslow and Herzberg look at the relationship between internal needs and the resulting effort expended to fulfil them, Vroom separates effort (which arises from motivation), performance, and outcomes. Vroom, hypothesises that in order for a person to be motivated that effort, performance and motivation must be linked. He proposes three variables to account for this, which he calls Valence, Expectancy and Instrumentality. Expectancy is the belief that increased effort will lead to increased performance i.e. if I work harder then this will be better. This is affected by such things as: 1. 2. 3. Having the right resources available (e.g. raw materials, time) Having the right skills to do the job Having the necessary support to get the job done (e.g. supervisor support, or correct information on the job)

Instrumentality is the belief that if you perform well that a valued outcome will be received i.e. if I do a good job, there is something in it for me. This is affected by such things as: 1. 2. 3. Clear understanding of the relationship between performance and outcomes e.g. the rules of the reward game Trust in the people who will take the decisions on who gets what outcome Transparency of the process that decides who gets what outcome

Valence is the importance that the individual places upon the expected outcome. For example, if I am mainly motivated by money, I might not value offers of additional time off. Having examined these links, the idea is that the individual then changes their level of effort according to the value they place on the outcomes they receive from the process and on their perception of the strength of the links between effort and outcome. So, if I perceive that any one of these is true: 1. 2. 3. My increased effort will not increase my performance My increased performance will not increase my rewards I dont value the rewards on offer

...then Vrooms expectancy theory suggests that this individual will not be motivated. This means that even if an organisation achieves two out of three, that employees would still not be motivated, all three are required for positive motivation. Here there is also a useful link to the Equity theory of motivation: namely that people will also compare outcomes for themselves with others. Equity theory suggests that people will alter the level of effort they put in to make it fair compared to others according to their perceptions. So if we got the same raise this year, but I think you put in a lot less effort, this theory suggests that I would scale back the effort I put in. Crucially, Expectancy theory works on perceptions so even if an employer thinks they have provided everything appropriate for motivation, and even if this works with most people in that organisation it doesnt mean that someone wont perceive that it doesnt work for them. At first glance this theory would seem most applicable to a traditional-attitude work situation where how motivated the employee is depends on whether they want the reward on offer for doing a good job and whether they believe more effort will lead to that reward. However, it could equally apply to any situation where someone does something because they expect a certain outcome. For example, I recycle paper because I think it's important to conserve resources and take a stand on environmental issues (valence); I think that the more effort I put into recycling the more paper I will recycle (expectancy); and I think that the more paper I recycle then less resources will be used (instrumentality) Thus, this theory of motivation is not about self-interest in rewards but about the associations people make towards expected outcomes and the contribution they feel they can make towards those outcomes. Other theories, in my opinion, do not allow for the same degree of individuality between people. This model takes into account individual perceptions and thus personal histories, allowing a richness of response not obvious in Maslow or McClelland, who assume that people are essentially all the same. Expectancy theory could also be overlaid over another theory (e.g. Maslow). Maslow could be used to describe which outcomes people are motivated by and Vroom to describe whether they will act based upon their experience and expectations. Formula : motivation=valence x expectancy(instrumentality)

1.

Expectancy theory is associated with the work of Vroom and Lawler/Porter (and others prior to this).

2.

Vroom applied concepts of

o o o

expectancy - If I tried could I do it? instrumentality - if I did it will I attain the required outcome? valence (a subjective value) - do I really value the available outcomes?

These are expressed as probabilities. Path-goal relationships are worked into explanation of motivation and performance at work. 3. The expectancy model seeks to elicit

a.

factors that shape the effort that someone puts into their job? Lawler/Porter focus on value of rewards/outcomes i.e. their attractiveness to the individual. For any person there is a range of outcomes that they desire. Some may hold aversion/negative value. Positive rewards are for Lawler/Porter reflect the needs suggested by Maslow with each person typically having a stable profile of preferences over time. This notion is akin to "subjective utility". a subjective probability that these rewards will result from effort i.e. the person's perception of the likeihood of reward success if he/she puts in the effort. This combine the probability that rewards depend on performance and that performance depends on effort. b. factors affecting the effort-performance relationship. Lawler/Porter argue that effort is not synonymous with performance. The important matters are the catch all of ability (including personality traits) - individual differences: intelligence, skills, aptitudes etc and perceptions of role (activities and behavours the person feels they should be engaged in to do the performance successfully) . The well-known Lawler/Porter diagram of expectancy relationships is as follows.

Discussion The model suggests that people at work are motivated to perform because of expectations as to perceived payoffs or rewards arising from that performance. The desireability of these (valence), perception of expectancy and force of expression are intrinsic to the person . Each one has their view of what is challenging or interesting, important to self-esteem and regard for extrinsic payoffs - pay and material rewards Expectancy depicts a subjective not "other-defined objective reality". It is how you/I see the world around use. Our perception of the worth of the payoffs available and attainable affects the degree of motivation.

Herzberg, Frederick (1923-2000): Well-known for his two-factor theory of job satisfaction. According to Herzberg, every organization has a set of hygiene factors like working conditions, salary, etc. The absence of hygiene factors creates employee dissatisfaction but their presence does not improve satisfaction. Herzberg found five factors in particular that were strong determinants of job satisfaction: achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility and advancement. Motivators (satisfiers) are associated with a long-term positive impact on job performance. In contrast, hygiene factors produce only short-term changes in job attitudes and performance, which quickly fall back to their previous level. Although Herzberg has been criticized for drawing conclusions about workers as a whole based on a study of accountants and engineers, his theory has proved very robust. Many firms have successfully put his methods into practice. Part of the reason for the popularity of his theory is that Herzberg has offered a practical approach to improving motivation through job enrichment, by redesigning workplaces and work systems. His Theory: Man has two sets of needs, one as an animal to avoid pain and the other as a human being to grow psychologically. The need for food, warmth, shelter and safety are hygiene needs. Whereas motivational needs are achievements through self-development. Frederick Herzberg proposed the Two Factor theory for human motivation. Satisfaction and psychological growth was a factor of motivation factors. Dissatisfaction was a result of hygiene factors. Frederick Herzberg decided to observe the key factors affecting a workers performance. He found that certain factors tended to cause a worker to feel unsatisfied with his or her job. The factors seemed to relate to the work environment. Some examples are: physical surroundings, supervisors and even the company itself. From this he developed a theory, he called, Hygiene Theory. According to his theory, for a worker to be happy and therefore productive, the environment factors must be comfortable for them. Although the removal of the environmental problems may make a worker productive, it will not necessarily motivate him. The question remains, "How can managers motivate employees?" Many managers believe that motivating employees requires giving rewards. Herzberg, however, believed that the workers get motivated through feeling responsible for and connected to their work. In this case, the work itself is rewarding. Managers can help the employees connect to their work by giving them more authority over the job, as well as offering direct and individual feedback. Other factors that can be related to the Hygiene Factor are:

Working conditions Salary Status Security Interpersonal Relations

Other factors that can be related to the Motivation Factors are:

Achievement Achievement Recognition Responsibility Advancement Growth

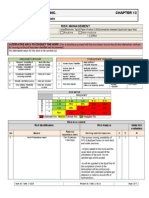

The combination of hygiene and motivation factors can result in 4 conditions:

1. 2. 3. 4.

High Hygiene/High Motivation: The ideal situation where employees are highly motivated and have few problems. High Hygiene/Low Motivation: Employees have few problems but are not highly motivated. Low Hygiene/High Motivation: Employees are motivated but have a lot of problems. Low Hygiene/Low Motivation: The worst situation. Unmotivated employees with lots of problems.

Herzbergs theories can be summarized by his quote, If you want people to do a good job, give them a good job to do. The two factor theory is useful because job context and content are major issues in the business world today. McGregor, Douglas (1906-1964): An American psychologist whose book THE HUMAN SIDE OF ENTERPRISE categorized managers into two types: Theory X and Theory Y. Many managers assume people to be work-shy and motivated primarily by money. These are Theory X managers. In contrast, Theory Y managers assume that workers look to gain satisfaction from employment. If achievement levels are low, managers must ask whether they are providing the right work environment. In other words, the Theory Y manager assumes that the blame for poor workforce performance lies with the management rather than the workers themselves. The Theory X manager assumes the following: Workers are motivated by money. Unless supervised closely, workers will under-perform. Workers will only respect a tough, decisive boss. Workers have no wish or ability to help make decisions. The Theory Y manager assumes the following: Workers seek job satisfaction, no less than managers. If trusted, workers will behave responsibly. Low performance is due to dull work or poor management. People have the desire and right to take part in decision making. McGegor was also against the traditional pay-for performance concept. He was convinced that money could not substitute an environment that was conducive to motivation. McGregor recognized the tremendous improvements in working conditions since the turn of the century, at all levels of the corporation. Drawing on Maslows hierarchy of needs, he argued that by satisfying the safety and security needs of its employees, companies had created higher-order needs. The focus had to shift to satisfying those higher needs. McGregors work is not completely original. Theory X is derived from the work of F W Taylor and from Adam Smiths notion of economic man. Theory Y stems clearly from Mayos human relations approach and Maslows work on human needs. Douglas McGregor, an American social psychologist, proposed his famous X-Y theory in his 1960 book 'The Human Side Of Enterprise'. Theory x and theory y are still referred to commonly in the field of management and motivation, and whilst more recent studies have questioned the rigidity of the model, Mcgregor's X-Y Theory remains a valid basic principle from which to develop positive management style and techniques. McGregor's XY Theory remains central to organizational development, and to improving organizational culture. McGregor's X-Y theory is a salutary and simple reminder of the natural rules for managing people, which under the pressure of day-to-day business are all too easily forgotten. McGregor maintained that there are two fundamental approaches to managing people. Many managers tend towards theory x, and generally get poor results. Enlightened managers use theory y, which produces better performance and results, and allows people to grow and develop.

theory x ('authoritarian management' style)

The average person dislikes work and will avoid it he/she can.

Therefore most people must be forced with the threat of punishment to work towards organisational objectives. The average person prefers to be directed; to avoid responsibility; is relatively unambitious, and wants security above all else. theory y ('participative management' style)

Effort in work is as natural as work and play.

People will apply self-control and self-direction in the pursuit of organisational objectives, without external control or the threat of punishment. Commitment to objectives is a function of rewards associated with their achievement. People usually accept and often seek responsibility.

The capacity to use a high degree of imagination, ingenuity and creativity in solving organisational problems is widely, not narrowly, distributed in the population. In industry the intellectual potential of the average person is only partly utilised.

tools for teaching, understanding and evaluating xy theory factors The XY Theory diagram and measurement tool below (pdf and doc versions) are adaptations of McGregor's ideas for modern organizations, management and work. They were not created by McGregor. I developed them to help understanding and application of McGregor's XY Theory concept. The test is a simple reflective tool, not a scientifically validated instrument; it's a learning aid and broad indicator. Please use it as such. free XY Theory diagram (pdf) free XY Theory diagram (doc version) free XY Theory test tool - personal and organizational - (pdf) free XY Theory test tool - personal and organizational - (doc version) same free XY Theory test tool - two-page version with clearer layout and scoring - (pdf) same free XY Theory test tool - two-page version with clearer layout and scoring - (doc version)

characteristics of the x theory manager Perhaps the most noticeable aspects of McGregor's XY Theory - and the easiest to illustrate are found in the behaviours of autocratic managers and organizations which use autocratic management styles. What are the characteristics of a Theory X manager? Typically some, most or all of these:

results-driven and deadline-driven, to the exclusion of everything else intolerant

issues deadlines and ultimatums distant and detached aloof and arrogant elitist short temper shouts issues instructions, directions, edicts issues threats to make people follow instructions demands, never asks does not participate does not team-build unconcerned about staff welfare, or morale proud, sometimes to the point of self-destruction one-way communicator poor listener fundamentally insecure and possibly neurotic anti-social vengeful and recriminatory does not thank or praise withholds rewards, and suppresses pay and remunerations levels scrutinises expenditure to the point of false economy seeks culprits for failures or shortfalls

seeks to apportion blame instead of focusing on learning from the experience and preventing recurrence does not invite or welcome suggestions takes criticism badly and likely to retaliate if from below or peer group poor at proper delegating - but believes they delegate well thinks giving orders is delegating holds on to responsibility but shifts accountability to subordinates relatively unconcerned with investing in anything to gain future improvements unhappy

how to manage upwards - managing your X theory boss

Working for an X theory boss isn't easy - some extreme X theory managers make extremely unpleasant managers, but there are ways of managing these people upwards. Avoiding confrontation (unless you are genuinely being bullied, which is a different matter) and delivering results are the key tactics.

Theory X managers (or indeed theory Y managers displaying theory X behaviour) are primarily results oriented - so orientate your your own discussions and dealings with them around results - ie what you can deliver and when.

Theory X managers are facts and figures oriented - so cut out the incidentals, be able to measure and substantiate anything you say and do for them, especially reporting on results and activities.

Theory X managers generally don't understand or have an interest in the human issues, so don't try to appeal to their sense of humanity or morality. Set your own objectives to meet their organisational aims and agree these with the managers; be seen to be selfstarting, self-motivating, self-disciplined and well-organised - the more the X theory manager sees you are managing yourself and producing results, the less they'll feel the need to do it for you.

Always deliver your commitments and promises. If you are given an unrealistic task and/or deadline state the reasons why it's not realistic, but be very sure of your ground, don't be negative; be constructive as to how the overall aim can be achieved in a way that you know you can deliver.

Stand up for yourself, but constructively - avoid confrontation. Never threaten or go over their heads if you are dissatisfied or you'll be in big trouble afterwards and life will be a lot more difficult.

If an X theory boss tells you how to do things in ways that are not comfortable or right for you, then don't questioning the process, simply confirm the end-result that is required, and check that it's okay to 'streamline the process' or 'get things done more efficiently' if the chance arises - they'll normally agree to this, which effectively gives you control over the 'how', provided you deliver the 'what' and 'when'. And this is really the essence of managing upwards X theory managers - focus and get agreement on the results and deadlines - if you consistently deliver, you'll increasingly be given more leeway on how you go about the tasks, which amounts to more freedom. Be aware also that many X theory managers are forced to be X theory by the short-term demands of the organisation and their own superiors - an X theory manager is usually someone with their own problems, so try not to give them any more. See also the article about building self-confidence, and assertiveness techniques.

theory z - william ouchi First things first - Theory Z is not a Mcgregor idea and as such is not Mcgregor's extension of his XY theory. Theory Z was developed by not by Mcgregor, but by William Ouchi, in his book 1981 'Theory Z: How American management can Meet the Japanese Challenge'. William Ouchi is professor of management at UCLA, Los Angeles, and a board member of several large US organisations. Theory Z is often referred to as the 'Japanese' management style, which is essentially what it is. It's interesting that Ouchi chose to name his model 'Theory Z', which apart from anything else tends to give the impression that it's a Mcgregor idea. One wonders if the idea was not considered strong enough to stand alone with a completely new name... Nevertheless, Theory

Z essentially advocates a combination of all that's best about theory Y and modern Japanese management, which places a large amount of freedom and trust with workers, and assumes that workers have a strong loyalty and interest in team-working and the organisation. Theory Z also places more reliance on the attitude and responsibilities of the workers, whereas Mcgregor's XY theory is mainly focused on management and motivation from the manager's and organisation's perspective. There is no doubt that Ouchi's Theory Z model offers excellent ideas, albeit it lacking the simple elegance of Mcgregor's model, which let's face it, thousands of organisations and managers around the world have still yet to embrace. For this reason, Theory Z may for some be like trying to manage the kitchen at the Ritz before mastering the ability to cook a decent fried breakfast. Theory Z is an approach to management based upon a combination of American and Japanese management philosophies and characterized by, among other things, long-term job security, consensual decision making, slow evaluation and promotion procedures, and individual responsibility within a group context. Proponents of Theory Z suggest that it leads to improvements in organizational performance. The following sections highlight the development of Theory Z, Theory Z as an approach to management including each of the characteristics noted above, and an evaluation of Theory Z. Realizing the historical context in which Theory Z emerged is helpful in understanding its underlying principles. The following section provides this context. Development of Theory Z Theory Z has been called a sociological description of the humanistic organizations advocated by management pioneers such as Elton Mayo, Chris Argyris, Rensis Likert, and Douglas McGregor. In fact, the descriptive phrase, "Theory Z." can be traced to the work of Douglas McGregor in the 1950s and 1960s. McGregor, a psychologist and college president, identified a negative set of assumptions about human nature, which he called Theory X. He asserted that these assumptions limited the potential for growth of many employees. McGregor presented an alternative set of assumptions that he called Theory Y and were more positive about human nature as it relates to employees. In McGregor's view, managers who adopted Theory Y beliefs would exhibit different, more humanistic, and ultimately more effective management styles. McGregor's work was read widely, and Theory Y became a wellknown prescription for improving management practices. But in the 1970s and 1980s, many United States industries lost market share to international competitors, particularly Japanese companies. Concerns about the competitiveness of U. S. companies led some to examine Japanese management practices for clues to the success enjoyed by many of their industries. This led to many articles and books purporting to explain the success of Japanese companies. It was in this atmosphere that Theory Z was introduced into the management lexicon. Theory Z was first identified as a unique management approach by William Ouchi. Ouchi contrasted American types of organizations(Type A) that were rooted in the United States' tradition of individualism with Japanese organizations (Type J) that drew uponthe Japanese heritage of collectivism. He argued that an emerging management philosophy, which came to be called Theory Z, would allow organizations to enjoy many of the advantages of

both systems. Ouchi presented his ideas fully in the 1981 book, Theory Z: How American Companies Can Meet the Japanese Challenge. This book was among the best-selling management books of the 1980s. Professor Ouchi advocated a modified American approach to management that would capitalize on the best characteristics of Japanese organizations while retaining aspects of management that are deeply rooted in U.S. traditions of individualism. Ouchi cited several companies as examples of Type Z organizations and proposed that a Theory Z management approach could lead to greater employee job satisfaction, lower rates of absenteeism and turnover, higher quality products, and better overall financial performance for U.S. firms adapting Theory Z management practices. The next section discusses Ouchi's suggestions for forging Theory Z within traditional American organizations. Theory Z as an Approachto Management Theory Z represents a humanistic approach to management. Although it is based on Japanese management principles, it is not a pure form of Japanese management. Instead, Theory Z is a hybrid management approach combining Japanese management philosophies with U.S. culture. In addition, Theory Z breaks away from McGregor's Theory Y. Theory Y is a largely psychological perspective focusing on individual dyads of employer-employee relationships while Theory Z changes the level of analysis to the entire organization. According to Professor Ouchi, Theory Z organizations exhibit a strong, homogeneous set of cultural values that are similar to clan cultures. The clan culture is characterized by homogeneity of values, beliefs, and objectives. Clan cultures emphasize complete socialization of members to achieve congruence of individual and group goals. Although Theory Z organizations exhibit characteristics of clan cultures, they retain some elements of bureaucratic hierarchies, such as formal authority relationships, performance evaluation, and some work specialization. Proponents of Theory Z suggest that the common cultural values should promote greater organizational commitment among employees. The primary features of Theory Z are summarized in the paragraphs that follow. Long-Term Employment Traditional U.S. organizations are plagued with short-term commitments by employees, but employers using more traditional management perspective may inadvertently encourage this by treating employees simply as replaceable cogs in the profit-making machinery. In the United States, employment at will, which essentially means the employer or the employee can terminate the employment relationship at any time, has been among the dominant forms of employment relationships. Conversely, Type Jorganizations generally make life-long commitments to their employees and expect loyalty in return, but Type J organizationsset the conditions to encourage this. This promotes stability in the organization and job security among employees. Consensual Decision Making

The Type Z organization emphasizes communication, collaboration, and consensus in decision making. This marks a contrast from the traditional Type A organization that emphasizes individual decision-making. Individual Responsibility Type A organizations emphasize individual accountability andperformance appraisal. Traditionally, performance measures in Type J companies have been oriented to the group. Thus, Type Zorganizations retain the emphasis on individual contributions that are characteristic of most American firms by recognizing individual achievements, albeit within the context of the wider group. Slow Evaluation and Promotion The Type A organization has generally been characterized by short-term evaluations of performance and rapid promotion of high achievers. The Type J organization, conversely, adopts the Japanese model of slow evaluation and promotion. Informal Controlwith Formalized Measures The Type Z organization relies on informal methods of control, but does measure performance through formal mechanisms. This is an attempt to combine elements of both the Type A and Type Jorganizations. Moderately Specialized Career Path Type A organizations have generally had quite specialized career paths, with employees avoiding jumps from functional area to another. Conversely, the Type J organization has generally had quite non-specialized career paths. The Type Z organization adopts a middle-ofthe-road posture, with career paths that are less specialized than the traditional U.S. model but more specialized than the traditional Japanese model. Holistic Concern The Type Z organization is characterized by concern for employees that goes beyond the workplace. This philosophy is more consistent with the Japanese model than the U.S. model. Evaluation of Theory Z Research into whether Theory Z organizations outperform others has yielded mixed results. Some studies suggest that Type Zorganizations achieve benefits both in terms of employee satisfaction, motivation, and commitment as well as in terms offinancial performance. Other studies conclude that Type Zorganizations do not outperform other organizations. Difficulties in the Japanese economy in the 1990s led some researchers to suggest that the widespread admiration of Japanese management practices in the 1970s and 1980s might have been misplaced. As a result, Theory Z has also received considerable criticism. It is unclear whether Theory Z will have a lasting impact on management practices in the U. S. and around

the world into the twenty-first century, but by positioning target research at the organizational level rather then the individual level, Ouchi will surely leave his mark on management practice for years to come.

Reinforcement theory is the process of shaping behavior by controlling the consequences of the behavior. In reinforcement theory a combination of rewards and/or punishments is used to reinforce desired behavior or extinguish unwanted behavior. Any behavior that elicits a consequence is called operant behavior, because the individual operates on his or her environment. Reinforcement theory concentrates on the relationship between the operant behavior and the associated consequences, and is sometimes referred to as operant conditioning.

BACKGROUND AND DEVELOPMENT OF REINFORCEMENT THEORY

Behavioral theories of learning and motivation focus on the effect that the consequences of past behavior have on future behavior. This is in contrast to classical conditioning, which focuses on responses that are triggered by stimuli in an almost automatic fashion. Reinforcement theory suggests that individuals can choose from several responses to a given stimulus, and that individuals will generally select the response that has been associated with positive outcomes in the past. E.L. Thorndike articulated this idea in 1911, in what has come to be known as the law of effect. The law of effect basically states that, all other things being equal, responses to stimuli that are followed by satisfaction will be strengthened, but responses that are followed by discomfort will be weakened.

B.F. Skinner was a key contributor to the development of modern ideas about reinforcement theory. Skinner argued that the internal needs and drives of individuals can be ignored because people learn to exhibit certain behaviors based on what happens to them as a result of their behavior. This school of thought has been termed the behaviorist, or radical behaviorist, school.

REINFORCEMENT, PUNISHMENT, AND EXTINCTION

The most important principle of reinforcement theory is, of course, reinforcement. Generally speaking, there are two types of reinforcement: positive and negative. Positive reinforcement results when the occurrence of a valued behavioral consequence has the effect of strengthening the probability of the behavior being repeated. The specific behavioral consequence is called a reinforcer. An example of positive reinforcement might be a salesperson that exerts extra effort to meet a sales quota (behavior) and is then rewarded with a bonus (positive reinforcer). The administration of the positive reinforcer should make it more likely that the salesperson will continue to exert the necessary effort in the future.

Negative reinforcement results when an undesirable behavioral consequence is withheld, with the effect of strengthening the probability of the behavior being repeated. Negative reinforcement is often confused with punishment, but they are not the same. Punishment attempts to decrease the probability of specific behaviors; negative reinforcement attempts to increase desired behavior. Thus, both positive and negative reinforcement have the effect of increasing the probability that a particular behavior will be learned and repeated. An example of negative reinforcement might be a salesperson that exerts effort to increase sales in his or her sales territory (behavior), which is followed by a decision not to reassign the salesperson to an undesirable sales route (negative reinforcer). The administration of the negative reinforcer should make it more likely that the salesperson will continue to exert the necessary effort in the future.

As mentioned above, punishment attempts to decrease the probability of specific behaviors being exhibited. Punishment is the administration of an undesirable behavioral consequence in order to reduce the occurrence of the unwanted behavior. Punishment is one of the more commonly used reinforcement-theory strategies, but many learning experts suggest that it should be used only if positive and negative reinforcement cannot be used or have previously failed, because of the potentially negative side effects of punishment. An example of punishment might be demoting an employee who does not meet performance goals or suspending an employee without pay for violating work rules.

Extinction is similar to punishment in that its purpose is to reduce unwanted behavior. The process of extinction begins when a valued behavioral consequence is withheld in order to decrease the probability that a learned behavior will continue. Over time, this is likely to result in the ceasing of that behavior. Extinction

may alternately serve to reduce a wanted behavior, such as when a positive reinforcer is no longer offered when a desirable behavior occurs. For example, if an employee is continually praised for the promptness in which he completes his work for several months, but receives no praise in subsequent months for such behavior, his desirable behaviors may diminish. Thus, to avoid unwanted extinction, managers may have to continue to offer positive behavioral consequences.

SCHEDULES OF REINFORCEMENT

The timing of the behavioral consequences that follow a given behavior is called the reinforcement schedule. Basically, there are two broad types of reinforcement schedules: continuous and intermittent. If a behavior is reinforced each time it occurs, it is called continuous reinforcement. Research suggests that continuous reinforcement is the fastest way to establish new behaviors or to eliminate undesired behaviors. However, this type of reinforcement is generally not practical in an organizational setting. Therefore, intermittent schedules are usually employed. Intermittent reinforcement means that each instance of a desired behavior is not reinforced. There are at least four types of intermittent reinforcement schedules: fixed interval, fixed ratio, variable interval, and variable ratio.

Fixed interval schedules of reinforcement occur when desired behaviors are reinforced after set periods of time. The simplest example of a fixed interval schedule is a weekly paycheck. A fixed interval schedule of reinforcement does not appear to be a particularly strong way to elicit desired behavior, and behavior learned in this way may be subject to rapid extinction. The fixed ratio schedule of reinforcement applies the reinforcer after a set number of occurrences of the desired behaviors. One organizational example of this schedule is a sales commission based on number of units sold. Like the fixed interval schedule, the fixed ratio schedule may not produce consistent, long-lasting, behavioral change.

Variable interval reinforcement schedules are employed when desired behaviors are reinforced after varying periods of time. Examples of variable interval schedules would be special recognition for successful performance and promotions to higher-level positions. This reinforcement schedule appears to elicit desired behavioral change that is resistant to extinction.

Finally, the variable ratio reinforcement schedule applies the reinforcer after a number of desired behaviors have occurred, with the number changing from situation to situation. The most common example of this reinforcement schedule is the slot machine in a casino, in which a different and unknown number of desired behaviors (i.e., feeding a quarter into the machine) is required before the reward (i.e., a jackpot) is realized. Organizational examples of variable ratio schedules are bonuses or special awards that are applied after varying numbers of desired behaviors occur. Variable ratio schedules appear to produce desired behavioral change that is consistent and very resistant to extinction.

REINFORCEMENT THEORY APPLIED TO ORGANIZATIONAL SETTINGS

Probably the best-known application of the principles of reinforcement theory to organizational settings is called behavioral modification, or behavioral contingency management. Typically, a behavioral modification program consists of four steps:

1. 2. 3. 4.

Specifying the desired behavior as objectively as possible. Measuring the current incidence of desired behavior. Providing behavioral consequences that reinforce desired behavior. Determining the effectiveness of the program by systematically assessing behavioral change.

Reinforcement theory is an important explanation of how people learn behavior. It is often applied to organizational settings in the context of a behavioral modification program. Although the assumptions of reinforcement theory are often criticized, its principles continue to offer important insights into individual learning and motivation.

You might also like

- Womens Movements in IndiaDocument23 pagesWomens Movements in Indiagangadhar119100% (1)

- Dances of IndiaDocument7 pagesDances of Indiagangadhar119No ratings yet

- Dances of IndiaDocument7 pagesDances of Indiagangadhar119No ratings yet

- Devlopment and DependencyDocument7 pagesDevlopment and Dependencygangadhar119No ratings yet

- James Allen Eight Pillars of ProsperityDocument121 pagesJames Allen Eight Pillars of Prosperitygangadhar119No ratings yet

- Rashtriya Swasthya Bima YojanaDocument1 pageRashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojanagangadhar119No ratings yet

- James Allen Eight Pillars of ProsperityDocument121 pagesJames Allen Eight Pillars of Prosperitygangadhar119No ratings yet

- The Mastery of Destiny - James AllenDocument41 pagesThe Mastery of Destiny - James AllenShawn100% (3)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- NDE Level II JobDocument3 pagesNDE Level II JobHelen TrippNo ratings yet

- Social Welfare Laws: Short Title. - This Act Shall Be Known As "The Anti-Rape Law of 1997."Document10 pagesSocial Welfare Laws: Short Title. - This Act Shall Be Known As "The Anti-Rape Law of 1997."gheljoshNo ratings yet

- AAA Code Promotes Ethics in Property AssessmentDocument13 pagesAAA Code Promotes Ethics in Property AssessmentMatei MarianNo ratings yet

- Wegmans Case Study on Strong Organizational CultureDocument20 pagesWegmans Case Study on Strong Organizational CultureBhagyashree Baruah100% (1)

- City of Dallas AD2-51Document19 pagesCity of Dallas AD2-51mhashimotoNo ratings yet

- NYCOSH Letter To DOB Re: OSHA Card Arrests 10262015Document2 pagesNYCOSH Letter To DOB Re: OSHA Card Arrests 10262015Monica NovoaNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management FRAmework ModelDocument5 pagesHuman Resource Management FRAmework ModelihmrishabhNo ratings yet

- Ielets General ReadingDocument29 pagesIelets General Readinglayal mrowehNo ratings yet

- DOCSNT #1119481 v1 Complaint PDFDocument14 pagesDOCSNT #1119481 v1 Complaint PDFClara-Sophia DalyNo ratings yet

- American Style Resume GuidelinesDocument3 pagesAmerican Style Resume GuidelinesJames GordonNo ratings yet

- Cidb Standard Form of Contract 2000Document127 pagesCidb Standard Form of Contract 2000SzeJinTan100% (2)

- Viraj Exports Employee Absenteeism ReportDocument108 pagesViraj Exports Employee Absenteeism ReportMichael WellsNo ratings yet

- Employment Documentation Form: American Culinary FederationDocument1 pageEmployment Documentation Form: American Culinary FederationALMusriALSudaniNo ratings yet

- Human Resources Assistant Resume, HR, Example, Sample, Employment, Work Duties, Cover LetterDocument3 pagesHuman Resources Assistant Resume, HR, Example, Sample, Employment, Work Duties, Cover LetterDavid SabaflyNo ratings yet

- PMSDocument16 pagesPMSJasveen SawhneyNo ratings yet

- Ashley Dwarshuis - Resume 2018Document2 pagesAshley Dwarshuis - Resume 2018api-398855744No ratings yet

- Organizational Culture in 40 CharactersDocument18 pagesOrganizational Culture in 40 CharactersParva ChandaranaNo ratings yet

- TNSDC Recruitment 15 Senior Associate Project Associate Notification 1Document8 pagesTNSDC Recruitment 15 Senior Associate Project Associate Notification 1Kama RajNo ratings yet

- HR 2Document12 pagesHR 2GaneshNo ratings yet

- Midterm Ugbana Marc Lloyd MidtermDocument8 pagesMidterm Ugbana Marc Lloyd MidtermMarc Lloyd Mangila UgbanaNo ratings yet

- The Cost of Labour Is Determined by The Price Paid For Labour and The Quantity of Labour UsedDocument3 pagesThe Cost of Labour Is Determined by The Price Paid For Labour and The Quantity of Labour UsedBisag AsaNo ratings yet

- Movtivation & Retention Strategies at Microsoft (HR Perspective)Document18 pagesMovtivation & Retention Strategies at Microsoft (HR Perspective)Muhammad Omair75% (4)

- Employee Empowerment: A Case Study On Starbucks: Submitted To: Ma'am Shanza Submitted By: Namira SiddiqueDocument4 pagesEmployee Empowerment: A Case Study On Starbucks: Submitted To: Ma'am Shanza Submitted By: Namira SiddiquenamiraNo ratings yet

- Dgms Strategic Plan 2011Document68 pagesDgms Strategic Plan 2011gulab111No ratings yet

- Conversion Table For PressureDocument4 pagesConversion Table For Pressuredassi99No ratings yet

- Cis 49Document2 pagesCis 49tiagoulbraNo ratings yet

- Maral Brochure FinalDocument10 pagesMaral Brochure FinalHitechSoft HitsoftNo ratings yet

- Annex A Application Form For Promotion AppointmentDocument1 pageAnnex A Application Form For Promotion Appointmentkaizen shinichiNo ratings yet

- Compensation AdministrationDocument2 pagesCompensation Administrationfrancine olilaNo ratings yet

- HRM Case Study On "Travails of A Training Manager"Document11 pagesHRM Case Study On "Travails of A Training Manager"Ashish KattaNo ratings yet