Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bernoulli's principle and venturi effect in carburetors

Uploaded by

yad1020Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bernoulli's principle and venturi effect in carburetors

Uploaded by

yad1020Copyright:

Available Formats

Principles

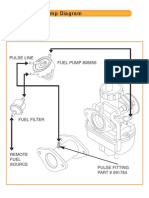

The carburetor works on Bernoulli's principle: the faster air moves, the lower its static pressure, and the higher its dynamic pressure. The throttle (accelerator) linkage does not directly control the flow of liquid fuel. Instead, it actuates carburetor mechanisms which meter the flow of air being pulled into the engine. The speed of this flow, and therefore its pressure, determines the amount of fuel drawn into the airstream. When carburetors are used in aircraft with piston engines, special designs and features are needed to prevent fuel starvation during inverted flight. Later engines used an early form of fuel injection known as a pressure carburetor. Most production carbureted (as opposed to fuel-injected) engines have a single carburetor and a matching intake manifold that divides and transports the air fuel mixture to the intake valves, though some engines (like motorcycle engines) use multiple carburetors on split heads. Multiple carburetor engines were also common enhancements for modifying engines in the USA from the 1950s to mid-1960s, as well as during the following decade of high-performance muscle cars fueling different chambers of the engine's intake manifold. Older engines used updraft carburetors, where the air enters from below the carburetor and exits through the top. This had the advantage of never "flooding" the engine, as any liquid fuel droplets would fall out of the carburetor instead of into the intake manifold; it also lent itself to use of an oil bath air cleaner, where a pool of oil below a mesh element below the carburetor is sucked up into the mesh and the air is drawn through the oil-covered mesh; this was an effective system in a time when paper air filters did not exist. Beginning in the late 1930s, downdraft carburetors were the most popular type for automotive use in the United States. In Europe, the sidedraft carburetors replaced downdraft as free space in the engine bay decreased and the use of the SU-type carburetor (and similar units from other manufacturers) increased. Some small propeller-driven aircraft engines still use the updraft carburetor design. Outboard motor carburetors are typically sidedraft, because they must be stacked one on top of the other in order to feed the cylinders in a vertically oriented cylinder block.

1979 Evinrude Type I marine sidedraft carburetor The main disadvantage of basing a carburetor's operation on Bernoulli's principle is that, being a fluid dynamic device, the pressure reduction in a venturi tends to be proportional to the square of the intake air speed. The fuel jets are much smaller and limited mainly by viscosity, so that the fuel flow tends to be proportional to the pressure difference. So jets sized for full power tend to starve the engine at lower speed and part throttle. Most commonly this has been corrected by using multiple jets. In SU and other movable jet carburetors, it was corrected by varying the jet size. For cold starting, a different principle was used in multi-jet carburetors. A flow resisting valve called a choke, similar to the throttle valve, was placed upstream of the main jet to reduce the intake pressure and suck additional fuel out of the jets.

Basic Carburetor Principles Carburetors, contrary to popular opinion, are a very basic device similar in relative design since Henry Ford and his Model T. The same basic things make them tick no matter who designed it. People over the years have heard horror stories about carburetors or maybe even had a bad experience firsthand (who hasnt been at the race track and witnessed a carburetor fire in their lifetime?) but that should not keep you from learning how one works. So without further ado, its time to dispel the myths, lies, and black magic. The first thing required for a carburetor to function properly is atmospheric pressure. Pressure is the most important variable tied to a carburetors performance, and without it one simply will not run! Most carburetors will have a vent tube that acts as a port to the fuel bowl; this port provides the carburetor with pressure from its ambient surroundings and forces the fuel to move through the metering passages as required based on engine demand. Manipulation or changing the length of the fuel bowl port can have dramatic affects on the fuel curve of a carburetor and should only be done with the assistance of a professional engine dyno. Many people think that fuel pressure is what moves fuel through a carburetor and they are which is incorrect. Fuel pressure simply pushes the fuel to the carburetor, atmospheric pressure takes over from there. Another phenomenon a carburetor requires is something we refer to as draw. Draw is essentially what the engine wants from the carburetor in terms of air and fuel. When an engine starts going through the RPM range, draw will increase (naturally as engine speed increases air and fuel demand will as well). As draw increases a carburetor must react to properly mix the air and fuel together. Air and fuel mixture is very important and varies depending on the type of fuel you use as well the elevation you are racing at. The word carburetor gurus use for the process of mixing air with fuel is atomization. Atomization is where things get tricky and some black magic comes to play; carburetor manufacturers, modifiers and other fuel system related companies are always searching for more efficient ways to atomize fuel and air. So how does the atomized fuel get to where it needs to be? This is a question that many might know the answer to - the Venturi effect - named after the Italian physicist Giovanni Venturi, the Venturi effect is a phenomenon where pressure is reduced after air flows through a constricted area. The constricted area in question is easy to spot as it is the skinniest part of the barrel on a carburetor. To explain a little further, air rushes past the area with the smallest circumference causing it to speed up and form an area of low pressure right below the venturi, this low pressure will in turn pull (remember our term draw) atomized fuel from the booster venturi and send it along to the intake runners. One thing nearly all carburetors have in common no matter how many barrels is the venturi. To sum it up; a carburetor will not run without atmospheric pressure, something to mix the fuel and a means of getting the fuel to combustion chamber - these are the basics and the details are where performance is found. Carburetor development has come a long way since Henry Fords Model T and each new season of racing brings some innovation giving racers an edge. Still foggy on the principals or want to know more? Give us a call, we love talking about these contraptions and helping people make the most of their race car.

You might also like

- What Is An EngineDocument15 pagesWhat Is An Engineravidra markapudiNo ratings yet

- Contents:: Name:Veeravalli Sunil Varma ROLL NO:17221A0371Document9 pagesContents:: Name:Veeravalli Sunil Varma ROLL NO:17221A0371Sunil Varma VeeravalliNo ratings yet

- Porting and Cylinder ScavengingDocument2 pagesPorting and Cylinder Scavenging69x4No ratings yet

- Carburettors Mikuni 33Document4 pagesCarburettors Mikuni 33Tegees TegeesovNo ratings yet

- CamshaftDocument5 pagesCamshaftPrabha KaranNo ratings yet

- Amal Tuning GuideDocument2 pagesAmal Tuning GuidegorlanNo ratings yet

- Bosch Fuel - TechDocument3 pagesBosch Fuel - TechMoaed KanbarNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis Motorcycle Swing Arm BracketDocument24 pagesDesign and Analysis Motorcycle Swing Arm Brackethafisilias0% (1)

- Minsk Repair ManualDocument60 pagesMinsk Repair ManualDavid Mondragon100% (1)

- Flowbench Design2 PDFDocument15 pagesFlowbench Design2 PDFsandy0% (1)

- HRC Manual - Honda NSR250R (MC28)Document48 pagesHRC Manual - Honda NSR250R (MC28)KICKERMAN360No ratings yet

- SAE Technical Paper FormatDocument2 pagesSAE Technical Paper FormatudaykanthNo ratings yet

- Understanding the fundamentals of camshafts in automotive enginesDocument8 pagesUnderstanding the fundamentals of camshafts in automotive enginesanshaj singhNo ratings yet

- TR8 Rom SupDocument32 pagesTR8 Rom SupClint CooperNo ratings yet

- How a 2-Stroke Engine WorksDocument6 pagesHow a 2-Stroke Engine WorksifzaeNo ratings yet

- Balancing of Crankshaft of Four Cylinder Engine, Dynamics of Machine, Ratnesh Raman Pathak, LpuDocument36 pagesBalancing of Crankshaft of Four Cylinder Engine, Dynamics of Machine, Ratnesh Raman Pathak, LpuRatnesh Raman PathakNo ratings yet

- Dyno BlairDocument10 pagesDyno BlairAntonino ScordatoNo ratings yet

- "Racing in Their Blood" Ch. 6 ExcerptDocument45 pages"Racing in Their Blood" Ch. 6 ExcerptBentley Publishers100% (2)

- Formula One Car DetailsDocument22 pagesFormula One Car DetailsBalaji AeroNo ratings yet

- Toaz - Info Graham Bell Two Stroke Performance Tuning PRDocument221 pagesToaz - Info Graham Bell Two Stroke Performance Tuning PRDeswita WitaNo ratings yet

- Scuderia Topolino - Technical AdviceDocument130 pagesScuderia Topolino - Technical AdviceNikNo ratings yet

- Animal Carb TuningDocument5 pagesAnimal Carb TuningRusty100% (1)

- Vincent TechnicalDocument58 pagesVincent TechnicalCiprian MaiorNo ratings yet

- Two Stroke AircraftDocument10 pagesTwo Stroke AircraftVinti Bhatia100% (1)

- Ducati 1199 Panigale Superquadro Engine - Over Square Design and Huge Power PDFDocument7 pagesDucati 1199 Panigale Superquadro Engine - Over Square Design and Huge Power PDFSarindran RamayesNo ratings yet

- 2017 Catalog Compressed PDFDocument140 pages2017 Catalog Compressed PDFDaniel DonosoNo ratings yet

- 1) Effect of Engine Speed On Intake Valve Flow Characteristics of A Diesel EngineDocument6 pages1) Effect of Engine Speed On Intake Valve Flow Characteristics of A Diesel EnginefitriasyrafNo ratings yet

- Puma Race Engines - Cylinder Head Modifications - Part 1: Valve SeatsDocument4 pagesPuma Race Engines - Cylinder Head Modifications - Part 1: Valve SeatsRobert DennisNo ratings yet

- How To Tune Carburetors, Step by Step - Cycle WorldDocument32 pagesHow To Tune Carburetors, Step by Step - Cycle WorldwillyhuaNo ratings yet

- Multi Valve SynopsisDocument11 pagesMulti Valve SynopsisiampiyushsahuNo ratings yet

- Desmo Drom IDocument5 pagesDesmo Drom IWilliamNo ratings yet

- Honda SOHC Four Lubritech Paint ScheduleDocument4 pagesHonda SOHC Four Lubritech Paint Schedulesetthe0% (1)

- Husqvarna Chain Saws: Workshop ManualDocument124 pagesHusqvarna Chain Saws: Workshop Manualnopublic78No ratings yet

- Spark Ignition and Pre-Chamber Turbulent Jet Ignition Combustion VisualizationDocument16 pagesSpark Ignition and Pre-Chamber Turbulent Jet Ignition Combustion VisualizationKaiser IqbalNo ratings yet

- Index For Holden H-G Series Bulletins Issued Durinf The Years 1949 and 1950Document2 pagesIndex For Holden H-G Series Bulletins Issued Durinf The Years 1949 and 1950Grant Millar100% (2)

- 2GR-FE Intake System Diagnosis and TestingDocument7 pages2GR-FE Intake System Diagnosis and TestingMenzie Peter RefolNo ratings yet

- Tuning SU CarburettorDocument25 pagesTuning SU Carburettorcrkg100% (1)

- HondaDocument37 pagesHondaPAVAN KALYAN AMGOTH100% (1)

- Enhancement of Combustion by Means of Squish Pistons: Key Words: Gasoline Engine, Combustion, Knocking, PistonDocument10 pagesEnhancement of Combustion by Means of Squish Pistons: Key Words: Gasoline Engine, Combustion, Knocking, PistonOfi de MoNo ratings yet

- Volkswagen Motorsport Celebrates 50 YearsDocument61 pagesVolkswagen Motorsport Celebrates 50 YearsVWvortex100% (1)

- CarburettorDocument67 pagesCarburettorKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Thesis Maioglou Dimitrios MSC SPD 2017 1106140007Document67 pagesDissertation Thesis Maioglou Dimitrios MSC SPD 2017 1106140007BIKASH100% (2)

- Applications of EngineDocument22 pagesApplications of EngineHari PrasadNo ratings yet

- Valve Timing Study of A Single Cylinder Motorcycle EngineDocument25 pagesValve Timing Study of A Single Cylinder Motorcycle EnginenicewiseNo ratings yet

- NSF250R PRESS INFORMATIONDocument24 pagesNSF250R PRESS INFORMATIONGuy ProcterNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis of Camshafts (DOHC)Document23 pagesDesign and Analysis of Camshafts (DOHC)Esaam Jamil0% (3)

- EFI Two StrokeDocument6 pagesEFI Two StrokegkarthikeyanNo ratings yet

- Cumbusiton Test WurthDocument1 pageCumbusiton Test WurthDiogov32No ratings yet

- F1-Cars SeminarsDocument25 pagesF1-Cars Seminarsphantaman100% (1)

- Amal Concentric HintsDocument8 pagesAmal Concentric HintsJohn NeweyNo ratings yet

- Carb Jett Jet SizesDocument54 pagesCarb Jett Jet Sizessaul acostaNo ratings yet

- Lap Sim EngineDocument5 pagesLap Sim Engineblack_oneNo ratings yet

- Lc4 BST 40 BibleDocument13 pagesLc4 BST 40 BibleAngélica Bayón González100% (1)

- Holsetturbo Productionspecs PDFDocument1 pageHolsetturbo Productionspecs PDFJulio Eduardo Candia AmpueroNo ratings yet

- DS L275eDocument2 pagesDS L275edespadaNo ratings yet

- Bultaco Swingarm Needle Roller Conversion Installation Guide R1Document6 pagesBultaco Swingarm Needle Roller Conversion Installation Guide R1Steve NewmanNo ratings yet

- Development Trends of Desmodromic Timing SystemsDocument29 pagesDevelopment Trends of Desmodromic Timing SystemsFabio Guedes100% (1)

- DCOE 40 MM Carb SettingDocument24 pagesDCOE 40 MM Carb SettingBrandon GilsonNo ratings yet

- Aisi 1020 SteelDocument1 pageAisi 1020 SteelTushar SaxenaNo ratings yet

- MechanicalDocument5 pagesMechanicalGaurav MakwanaNo ratings yet

- Lec3 Robot TechnologyDocument19 pagesLec3 Robot TechnologyPriya SubramanianNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of RoboticsDocument19 pagesFundamentals of RoboticsdharshanirymondNo ratings yet

- BT CottonDocument84 pagesBT Cottonyad1020No ratings yet

- Gate2014 Brochure 2Document82 pagesGate2014 Brochure 2अजय प्रताप सिंहNo ratings yet

- HDO Post No 1 Final For ResultsDocument36 pagesHDO Post No 1 Final For Resultsyad1020No ratings yet

- MQLDocument1 pageMQLyad1020No ratings yet

- Minimum Quantity LubricationDocument7 pagesMinimum Quantity Lubricationyad1020No ratings yet

- Refrigeration & Air Conditioning Sector Director Technical Education & Industrial Training, Punjab, Chandigarh Category - GeneralDocument6 pagesRefrigeration & Air Conditioning Sector Director Technical Education & Industrial Training, Punjab, Chandigarh Category - Generalyad1020No ratings yet

- Single Cylinder Four Stroke Deisel EngineDocument6 pagesSingle Cylinder Four Stroke Deisel Engineyad1020No ratings yet

- Sakhi Series Part 1Document154 pagesSakhi Series Part 1Charanpal Singh100% (2)

- RACTest RigDocument6 pagesRACTest Rigyad1020No ratings yet

- Quantitative AptitudeDocument55 pagesQuantitative Aptituderamavarshny85% (13)

- Fabrication GeneralDocument6 pagesFabrication Generalyad1020No ratings yet

- Form - 1: To Be Submitted by Every Public Authority To Administrative Department by 04-01-2012Document1 pageForm - 1: To Be Submitted by Every Public Authority To Administrative Department by 04-01-2012yad1020No ratings yet

- HardfacingDocument1 pageHardfacingyad1020No ratings yet

- Spiritual Strength of Women PDFDocument22 pagesSpiritual Strength of Women PDFyad1020No ratings yet

- Total Quality Management (105903) Credit: 04 LTP 3 1 0Document1 pageTotal Quality Management (105903) Credit: 04 LTP 3 1 0yad1020No ratings yet

- Machine ToolsDocument17 pagesMachine Toolsyad1020No ratings yet

- Engineering Metrology and MeasurementsDocument35 pagesEngineering Metrology and MeasurementsPairu Muneendra Mithul100% (2)

- Course SubjectsDocument1 pageCourse Subjectsyad1020No ratings yet

- Gku Talwandi Sabo, SyllabusDocument84 pagesGku Talwandi Sabo, Syllabusyad1020No ratings yet

- Rifling: Navigation SearchDocument12 pagesRifling: Navigation Searchyad1020No ratings yet

- Rifling: Navigation SearchDocument12 pagesRifling: Navigation Searchyad1020No ratings yet

- Major Project Report DeadlinesDocument11 pagesMajor Project Report Deadlinesyad1020No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1526612510000320 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S1526612510000320 Main PDFyad1020No ratings yet

- Basic Thermodynamic CyclesDocument4 pagesBasic Thermodynamic Cyclesapi-3830954No ratings yet

- WeldingDocument2 pagesWeldingyad1020No ratings yet

- Events of National Importance 2016Document345 pagesEvents of National Importance 2016TapasKumarDashNo ratings yet

- Designers' Guide To Eurocode 7 Geothechnical DesignDocument213 pagesDesigners' Guide To Eurocode 7 Geothechnical DesignJoão Gamboias100% (9)

- Coating Inspector Program Level 1 Studen 1Document20 pagesCoating Inspector Program Level 1 Studen 1AhmedBalaoutaNo ratings yet

- A Review On Micro EncapsulationDocument5 pagesA Review On Micro EncapsulationSneha DharNo ratings yet

- Exp-1. Evacuative Tube ConcentratorDocument8 pagesExp-1. Evacuative Tube ConcentratorWaseem Nawaz MohammedNo ratings yet

- What Is A Lecher AntennaDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Lecher AntennaPt AkaashNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - 31-05-2023Document163 pagesChapter 6 - 31-05-2023Saumitra PandeyNo ratings yet

- CLOZE TEST Fully Revised For SSC, Bank Exams & Other CompetitiveDocument57 pagesCLOZE TEST Fully Revised For SSC, Bank Exams & Other CompetitiveSreenu Raju100% (2)

- Critical Thinking Essay-Animal Testing: Rough DraftDocument10 pagesCritical Thinking Essay-Animal Testing: Rough Draftjeremygcap2017No ratings yet

- Investigation of Twilight Using Sky Quality Meter For Isha' Prayer TimeDocument1 pageInvestigation of Twilight Using Sky Quality Meter For Isha' Prayer Timeresurgam52No ratings yet

- Math 101Document3 pagesMath 101Nitish ShahNo ratings yet

- 31 Legacy of Ancient Greece (Contributions)Document10 pages31 Legacy of Ancient Greece (Contributions)LyreNo ratings yet

- BA 302 Lesson 3Document26 pagesBA 302 Lesson 3ピザンメルビンNo ratings yet

- Spectro Xepos Brochure 2016Document8 pagesSpectro Xepos Brochure 2016Mary100% (1)

- 1993 - Kelvin-Helmholtz Stability Criteria For Stratfied Flow - Viscous Versus Non-Viscous (Inviscid) Approaches PDFDocument11 pages1993 - Kelvin-Helmholtz Stability Criteria For Stratfied Flow - Viscous Versus Non-Viscous (Inviscid) Approaches PDFBonnie JamesNo ratings yet

- TCBE - Conversation Skills TemplateDocument10 pagesTCBE - Conversation Skills TemplateAryoma GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Production of Formaldehyde From MethanolDocument200 pagesProduction of Formaldehyde From MethanolSofia Mermingi100% (1)

- The Production and Interpretation of Ritual Transformation Experience: A Study on the Method of Physical Actions of the Baishatun Mazu PilgrimageDocument36 pagesThe Production and Interpretation of Ritual Transformation Experience: A Study on the Method of Physical Actions of the Baishatun Mazu PilgrimageMinmin HsuNo ratings yet

- 16SEE - Schedule of PapersDocument36 pages16SEE - Schedule of PapersPiyush Jain0% (1)

- Small Healthcare Organization: National Accreditation Board For Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (Nabh)Document20 pagesSmall Healthcare Organization: National Accreditation Board For Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (Nabh)Dipti PatilNo ratings yet

- 21 Great Answers To: Order ID: 0028913Document13 pages21 Great Answers To: Order ID: 0028913Yvette HOUNGUE100% (1)

- Phenomenal Consciousness and Cognitive Access: ResearchDocument6 pagesPhenomenal Consciousness and Cognitive Access: ResearchAyşeNo ratings yet

- Packing, Transportation and Marketing of Ornamental FishesDocument16 pagesPacking, Transportation and Marketing of Ornamental Fishesraj kiranNo ratings yet

- Dball-Gm5 en Ig Cp20110328aDocument18 pagesDball-Gm5 en Ig Cp20110328aMichael MartinezNo ratings yet

- Adopt 2017 APCPI procurement monitoringDocument43 pagesAdopt 2017 APCPI procurement monitoringCA CANo ratings yet

- Kavanaugh On Philosophical EnterpriseDocument9 pagesKavanaugh On Philosophical EnterprisePauline Zoi RabagoNo ratings yet

- Transportation Geotechnics: Tirupan Mandal, James M. Tinjum, Tuncer B. EdilDocument11 pagesTransportation Geotechnics: Tirupan Mandal, James M. Tinjum, Tuncer B. EdilDaniel Juan De Dios OchoaNo ratings yet

- The Eukaryotic Replication Machine: D. Zhang, M. O'DonnellDocument39 pagesThe Eukaryotic Replication Machine: D. Zhang, M. O'DonnellÁgnes TóthNo ratings yet

- MAPEH 6- WEEK 1 ActivitiesDocument4 pagesMAPEH 6- WEEK 1 ActivitiesCatherine Renante100% (2)

- Workflowy - 2. Using Tags For NavigationDocument10 pagesWorkflowy - 2. Using Tags For NavigationSteveLangNo ratings yet