Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Declarative Sentence Symbols True False Truthbearers: Three Types of Proposition

Uploaded by

Merlie GotomangaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Declarative Sentence Symbols True False Truthbearers: Three Types of Proposition

Uploaded by

Merlie GotomangaCopyright:

Available Formats

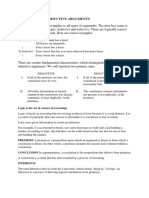

the term proposition refers to either (a) the "content" or"meaning" of a meaningful declarative sentence or (b) the pattern

of symbols, marks, or sounds that make up a meaningful declarative sentence. The meaning of a proposition includes having the quality or property of being either true or false, and as such propositions are claimed to be truthbearers. Three types of proposition There are three types of proposition: fact, value and policy. Proposition of Fact A proposition of fact is a statement in which you focus largely on belief of the audience in its truth or falsehood. Your arguments are thus aimed at getting your audience to accept the statement as being true or false. Proposition of Value In a proposition of values, you make a statement where you are asking your audience to make an evaluative judgment as to whether the statement is morally good or bad, right or wrong. This may be done by comparing two items and asking them which is better. Propositions of Policy A proportion of policy advocates a course of action. In this, you ask your audience to endorse a policy or to Inference is the act or process of deriving logical conclusions from premises known or assumed to be true.[1] The conclusion drawn is also called an idiomatic. The laws of valid inference are studied in the field of logic. Definition of MEDIATE INFERENCE : a logical inference drawn from more than one proposition or premise An immediate inference is an inference which can be made from only one statement or proposition. For instance, from the statement "All toads are green." we can make the immediate inference that "No toads are not green." There are a number of immediate inferences which can validly be made using logical operations, the result of which is a logically equivalent statement form to the given statement. There are also invalid immediate inferences which are syllogistic fallacies.

All of the following are thinking steps to prevent drawing false inferences 1. Verify and value the facts. 2. Assess prior knowledge. 3. Detect contradictions. An antecedent is the first half of a hypothetical proposition. Examples:

If P, then Q.

This is a nonlogical formulation of a hypothetical proposition. In this case, the antecedent is P, and the consequent is Q. In an implication, if implies then called the antecedent and is called the consequent.[1]

is

If X is a man, then X is mortal.

"X is a man" is the antecedent for this proposition.

If men have walked on the moon, then I am the king of France.

Here, "men have walked on the moon" is the antecedent. A consequent is the second half of a hypothetical proposition. In the standard form of such a proposition, it is the part that follows "then". In an implication, if implies then is called the antecedent and is called the consequent.[1] Examples:

If P, then Q.

Q is the consequent of this hypothetical proposition.

If X is a mammal, then X is an animal.

Here, "X is an animal" is the consequent.

If computers can think, then they are alive.

"They are alive" is the consequent. The consequent in a hypothetical proposition is not necessarily a consequence of the antecedent.

If monkeys are purple, then fish speak Klingon.

"Fish speak Klingon" is the consequent here, but intuitively is not a consequence of (nor does it have anything to do with) the claim made in the antecedent that "monkeys are purple". Informally, two kinds of logical reasoning can be distinguished in addition to formal deduction: induction and abduction. Given a precondition or premise, a conclusion or logical consequence and a rule or material conditional that implies the conclusion given the precondition, one can explain that:

Deductive reasoning determines whether the truth of a conclusion can be determined for that rule, based solely on the truth of the premises. Example: "When it rains, things outside get wet. The grass is outside, therefore: when it rains, the grass gets wet." Mathematical logic and philosophical logic are commonly associated with this style of reasoning. Inductive reasoning attempts to support a determination of the rule. It hypothesizes a rule after numerous examples are taken to be a conclusion that follows from a precondition in terms of such a rule. Example: "The grass got wet numerous times when it rained, therefore: the grass always gets wet when it rains." While they may be persuasive, these arguments are not deductively valid, see the problem of induction. Science is associated with this type of reasoning. Abductive reasoning selects a cogent set of preconditions. Given a true conclusion and a rule, it attempts to select some possible premises that, if true also, can support the conclusion, though not uniquely. Example: "When it rains, the grass gets wet. The grass is outside and nothing outside is dry, therefore: maybe it rained." Diagnosticians and detectives are commonly associated with this type of reasoning.

A syllogism (Greek: syllogismos "conclusion," "inference") is a kind of logical argument in which one proposition (the conclusion) is inferred from two or more others (the premises) of a specific form. Basic structure A categorical syllogism consists of three parts:

Major premise Minor premise Conclusion

Each part is a categorical proposition, and each categorical proposition contains two categorical terms.[7] In Aristotle, each of the premises is in the form "All A are B," "Some A are B", "No A are B" or "Some A are not B", where "A" is one term and "B" is another. "All A are B," and "No A are B" are termed universal propositions; "Some A are B" and "Some A are not B" are termed particular propositions. More modern logicians allow some variation. Each of the premises has one term in common with the conclusion: in a

major premise, this is the major term (i.e., the predicate of the conclusion); in a minor premise, it is the minor term (the subject) of the conclusion. For example: Major premise: All humans are mortal. Minor premise: All Greeks are humans. Conclusion: All Greeks are mortal. Each of the three distinct terms represents a category. In the above example, humans, mortal, and Greeks. Mortal is the major term, Greeks the minor term. The premises also have one term in common with each other, which is known as the middle term; in this example, humans. Both of the premises are universal, as is the conclusion. Major premise: All mortals die. Minor premise: Some mortals are men. Conclusion: Some men die. Here, the major term is die, the minor term is men, and the middle term is mortals. The major premise is universal; the minor premise and the conclusion are particular. A sorites is a form of argument in which a series of incomplete syllogisms is so arranged that the predicate of each premise forms the subject of the next until the subject of the first is joined with the predicate of the last in the conclusion. For example, if one argues that a given number of grains of sand does not make a heap and that an additional grain does not either, then to conclude that no additional amount of sand would make a heap is to construct a sorites argument. In classical logic, hypothetical syllogism is a valid argument form which is a syllogism having a conditional statement for one or both of its premises.[1][2] If I do not wake up, then I cannot go to work. If I cannot go to work, then I will not get paid. Therefore, if I do not wake up, then I will not get paid. In propositional logic, hypothetical syllogism is the name of a valid rule of inference[3][4] (often abbreviated HS and sometimes also called the chain argument, chain rule, or the principle of transitivity of implication). Hypothetical syllogism is one of the rules in classical logic that is not always accepted in certain systems of nonclassical logic. The rule may be stated:

where the rule is that whenever instances of " ", and " of a proof, " " can be placed on a subsequent line.

" appear on lines

Hypothetical syllogism is closely related and similar to disjunctive syllogism, in that it is also type of syllogism, and also the name of a rule of inference. Hypothetical syllogisms were already known and discussed in antiquity

CATEGORICAL PROPOSITIONS Categorical propositions divide the world into two distinct classes and make an assertion about members of those classes. Every categorical proposition is a statement about the members of two classes and their relationship to one another. For example, All geraniums are flowering plants. Some logicians are not rational thinkers.

Now we can formulate the syllogism above. The terms: A = "is a mammal" B = "is a lion" C = "Leo" (individual subject) Thus: AaB (all lions are mammals) BiC (some C, Leo, is a lion) _____ AiC (some C, Leo, is a mammal)

Now, in propositional logic, we would have to formulate this in terms of propositions. If we only use the sentences above, we will get A (all lions are mammals) B (Leo is a lion) ___ C (Leo is a mammal) An informal fallacy is an error in reasoning that does not originate in improper logical form. Arguments committing informal fallacies may be formally valid, but still fallacious. An error that stems from a poor logical form is sometimes called formal fallacy or simply an invalid argument.

There are many different informal fallacies, but a few basic types. For instance, material fallacies is error in what the arguer is talking about, while Verbal fallacies is error in how the arguer is talking. Fallacies of presumption fail to prove the conclusion by assuming the conclusion in the proof. Fallacies of weak inference fail to prove the conclusion with insufficient evidence. Fallacies of distraction fail to prove the conclusion with irrelevant evidence, like emotion. Fallacies of ambiguity fail to prove the conclusion due to vagueness in words, phrases, or grammar

You might also like

- Document Thinking-1Document17 pagesDocument Thinking-1claytontanaka7No ratings yet

- Deductive Reasoning: I. DefinitionDocument4 pagesDeductive Reasoning: I. DefinitionAc MIgzNo ratings yet

- Deductive Reasoning ReportDocument3 pagesDeductive Reasoning Reportnnaesor_1091No ratings yet

- Introduction To Philosophy and ArgumentsDocument15 pagesIntroduction To Philosophy and ArgumentsEmmanuel AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- 3 What Is An ArgumentDocument12 pages3 What Is An Argumentakhanyile943No ratings yet

- Logic 2 AssnDocument3 pagesLogic 2 AssnDeepu GuptaNo ratings yet

- 01 Legal LogicDocument14 pages01 Legal LogicAnonymous BBs1xxk96VNo ratings yet

- A Normative Account of Defeasible and PRDocument9 pagesA Normative Account of Defeasible and PRdex12384No ratings yet

- Logic by UmarDocument7 pagesLogic by UmarMuhammad Umar NaheedNo ratings yet

- Homework 1Document9 pagesHomework 1tu.ngohcmutproNo ratings yet

- Logic Final ExamDocument28 pagesLogic Final ExamDhen MarcNo ratings yet

- Intro To Philo LP - Arguments 22Document13 pagesIntro To Philo LP - Arguments 22Eljhon monteroNo ratings yet

- Copi and Cohen For Toolkit ChokDocument7 pagesCopi and Cohen For Toolkit Chokdanaya fabregasNo ratings yet

- SYLLOGISMDocument7 pagesSYLLOGISMJewel Lloyd Dizon GuintuNo ratings yet

- Alina Bradford Mindy Weisberger: Deductive Reasoning vs. Inductive ReasoningDocument4 pagesAlina Bradford Mindy Weisberger: Deductive Reasoning vs. Inductive Reasoninglehahai1802No ratings yet

- Logic Handout MUDocument40 pagesLogic Handout MUAbdi KhadirNo ratings yet

- Inductive and Deductive ResearchDocument3 pagesInductive and Deductive ResearchAbdullah HamidNo ratings yet

- Syllogistic Reasoning-Categorical SyllogismsDocument5 pagesSyllogistic Reasoning-Categorical SyllogismsTin EupenaNo ratings yet

- Logic Notes 5 6Document12 pagesLogic Notes 5 6Dhen MarcNo ratings yet

- Deductive and Inductive Arguments: A) Deductive: Every Mammal Has A HeartDocument9 pagesDeductive and Inductive Arguments: A) Deductive: Every Mammal Has A HeartUsama SahiNo ratings yet

- Induction and DeductionDocument2 pagesInduction and DeductionNethravathi Narayanaswamy100% (1)

- Notes: Victoria Int'l CollegeDocument17 pagesNotes: Victoria Int'l CollegeAnonymous 6RxKCAYNNo ratings yet

- Handout For Logic ExtensionDocument26 pagesHandout For Logic ExtensionkasimNo ratings yet

- Propositional CalculusDocument106 pagesPropositional CalculusPraveen Kumar100% (1)

- PHILOSOPHY ASSIGNMENT VarangDocument3 pagesPHILOSOPHY ASSIGNMENT VarangVARANG DIXITNo ratings yet

- Logic, Deductive and Inductive ArgumentDocument14 pagesLogic, Deductive and Inductive Argumentaroosa100% (1)

- Philosophy and LogicDocument24 pagesPhilosophy and Logichauwah202No ratings yet

- The PrinciplesDocument2 pagesThe PrinciplesMadhusudan DeodharNo ratings yet

- Legal Arguments & ReasoningDocument17 pagesLegal Arguments & ReasoningNasir MengalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document7 pagesChapter 3niczclueNo ratings yet

- XAT Reasoning TermsDocument4 pagesXAT Reasoning Termsaaryan.8912No ratings yet

- GST 111Document31 pagesGST 111AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Term - logic-WPS OfficeDocument6 pagesThe Term - logic-WPS OfficeALEX OMARNo ratings yet

- Argument Analysis & Evaluation in Philosophy.2Document5 pagesArgument Analysis & Evaluation in Philosophy.2nefiseNo ratings yet

- Deductive reasoning-WPS OfficeDocument7 pagesDeductive reasoning-WPS OfficeJerry G. GabacNo ratings yet

- Argument: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument9 pagesArgument: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchJef PerezNo ratings yet

- Propositional CalculusDocument191 pagesPropositional CalculusMatthew Allan RosalesNo ratings yet

- Inference Is The Act or Process of Deriving Logical Conclusions From Premises Known or Assumed ToDocument4 pagesInference Is The Act or Process of Deriving Logical Conclusions From Premises Known or Assumed Toagungputra45No ratings yet

- Question No 1: Answer:: Logic: MeaningDocument7 pagesQuestion No 1: Answer:: Logic: MeaningSana KhanNo ratings yet

- Notes in LogicDocument10 pagesNotes in LogicJoseph De Villa BobadillaNo ratings yet

- Logical ArgumentDocument4 pagesLogical Argumentapi-150536296No ratings yet

- SyllogismDocument31 pagesSyllogismyousuf pogiNo ratings yet

- Logic Chapter 3Document8 pagesLogic Chapter 3Laine QuijanoNo ratings yet

- Abductive ReasoningDocument13 pagesAbductive ReasoningpsfxNo ratings yet

- LOGICDocument19 pagesLOGICRolaine MarieNo ratings yet

- Inductive and Deductive ReasoningDocument28 pagesInductive and Deductive ReasoningJohn Rendell MoralesNo ratings yet

- 7.6 Sorites Sorites Is An Argument Whose Conclusion Is Inferred From Its Premises by A Chain of SyllogisticDocument10 pages7.6 Sorites Sorites Is An Argument Whose Conclusion Is Inferred From Its Premises by A Chain of SyllogisticKaren Sheila B. Mangusan - DegayNo ratings yet

- GST 112 Updated-1Document10 pagesGST 112 Updated-1Emmanuel DaviesNo ratings yet

- Logical ReasoningDocument15 pagesLogical ReasoningInsight MndyNo ratings yet

- LogicDocument5 pagesLogicHalimatNo ratings yet

- Unit-2 (38) CATEGORICAL SYLLOGISM PDFDocument13 pagesUnit-2 (38) CATEGORICAL SYLLOGISM PDFAnonymous 9hu7flNo ratings yet

- Chapter Five - Evaluating ArgumentsDocument32 pagesChapter Five - Evaluating ArgumentsSamuel AyladoNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four Judgment and Proposition What Is A Judgment?Document20 pagesChapter Four Judgment and Proposition What Is A Judgment?Alexander OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Short Summary About Deductive and Inductive ReasoningDocument3 pagesShort Summary About Deductive and Inductive ReasoningJamina JamalodingNo ratings yet

- ENG101A Freshman English: Logic and Argumentation IDocument74 pagesENG101A Freshman English: Logic and Argumentation ICharles MK ChanNo ratings yet

- Logic DictionaryDocument66 pagesLogic DictionaryInnu Tudu0% (1)

- III.1. Deductive Argumentation, Validity and SoundnessDocument22 pagesIII.1. Deductive Argumentation, Validity and SoundnessJavier Hernández IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Syllogistic ReasoningDocument17 pagesSyllogistic Reasoningnesuma100% (1)

- Deductive Reasoning Vs Inductive ReasoningDocument2 pagesDeductive Reasoning Vs Inductive ReasoningAc MIgzNo ratings yet

- Research Report LeadershipDocument10 pagesResearch Report Leadershipdassia_legorretaNo ratings yet

- CHCECE017 Student Assessment Task 3 - ScenariosDocument7 pagesCHCECE017 Student Assessment Task 3 - ScenariosDanica RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Communication Skills MCQs With Answers PDFDocument11 pagesCommunication Skills MCQs With Answers PDFjayitadebangiNo ratings yet

- Benefits of ReadingDocument7 pagesBenefits of ReadingCeleste GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Yr 8 Sci Task 9 Energy Converter-Mouse Trap Car-Student VersionDocument3 pagesYr 8 Sci Task 9 Energy Converter-Mouse Trap Car-Student Versionapi-398166017No ratings yet

- Empathy ProjectDocument1 pageEmpathy Projectapi-281965237No ratings yet

- ELearning-2014 BelgradeSerbia ProceedingsDocument146 pagesELearning-2014 BelgradeSerbia Proceedingsivo.kleber100No ratings yet

- The Metaphorical Meanings of Maroon 5'S Selected Song LyricsDocument101 pagesThe Metaphorical Meanings of Maroon 5'S Selected Song LyricsSalman 1stINANo ratings yet

- Lam Q4 Week 6 8Document19 pagesLam Q4 Week 6 8Chrisjon Gabriel EspinasNo ratings yet

- MPC 003 2020Document17 pagesMPC 003 2020Rajni KumariNo ratings yet

- Gum RoadDocument14 pagesGum RoadjohnlimshNo ratings yet

- The Use of Undercover Game Application To Improve Students' VocabularyDocument16 pagesThe Use of Undercover Game Application To Improve Students' VocabularyNina ResianaNo ratings yet

- NSE English10 LessonsLearnedDocument82 pagesNSE English10 LessonsLearnedjoshNo ratings yet

- Learning Style QuestionnaireDocument4 pagesLearning Style Questionnairemeymirah80% (5)

- The Internet Is An Indispensable Tool in Institutions of Higher Learning. DiscussDocument3 pagesThe Internet Is An Indispensable Tool in Institutions of Higher Learning. DiscussSimbarashe KareziNo ratings yet

- Mental Skills Training For Tennis Players An.11Document4 pagesMental Skills Training For Tennis Players An.11Paulo Tsuneta0% (1)

- Do You Know That Digits Have An End1Document20 pagesDo You Know That Digits Have An End1Smake JithNo ratings yet

- Ascilite 2015 DrafttopublishDocument5 pagesAscilite 2015 DrafttopublishRichiel SungaNo ratings yet

- VCE Psychology: Sample Teaching PlanDocument2 pagesVCE Psychology: Sample Teaching Planapi-526753145No ratings yet

- Landmark EducationDocument5 pagesLandmark Educationparag300067% (3)

- Systematic Reviews of The Literature: Journal Selection For Submitting A Systematic ReviewDocument3 pagesSystematic Reviews of The Literature: Journal Selection For Submitting A Systematic ReviewphyllidaNo ratings yet

- Mezirow, J. (1985) - A Critical Theory of Self-Directed Learning.Document14 pagesMezirow, J. (1985) - A Critical Theory of Self-Directed Learning.Piero Morata100% (1)

- JEE Main 2017 Official Question Paper 1 Set C, April 2Document232 pagesJEE Main 2017 Official Question Paper 1 Set C, April 2shantha kumarNo ratings yet

- Exam QuestionDocument8 pagesExam QuestionShiyamala SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- TechnologyDocument11 pagesTechnologyAnonymous GVWIlk3ZNo ratings yet

- JIC - Dubbing or Subtitling InterculturalismDocument8 pagesJIC - Dubbing or Subtitling InterculturalismDavidForloyoNo ratings yet

- STEP 1 IELTS Speaking Tips (E-Book)Document13 pagesSTEP 1 IELTS Speaking Tips (E-Book)Arnie TJ Hernandez Estrella100% (1)

- Teaching Philosophy StatementDocument2 pagesTeaching Philosophy StatementSUHAILNo ratings yet

- Adverbs AlexDocument11 pagesAdverbs AlexAlex Highlander MunteanuNo ratings yet

- Personal ReflectionDocument4 pagesPersonal ReflectionAndrewSmith100% (1)