Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pan Africanism and Pan Somalism By: I.M. Lewis

Uploaded by

AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pan Africanism and Pan Somalism By: I.M. Lewis

Uploaded by

AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriCopyright:

Available Formats

Pan-Africanism and Pan-Somalism Author(s): I. M. Lewis Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 1, No.

2 (Jun., 1963), pp. 147-161 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/159026 . Accessed: 25/01/2013 15:00

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern African Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Journal of ModernAfricanStudies,I, 2 (1963), pp. 147-161

and Pan-Africanism Pan-Somalism

BY I. M. LEWIS*

attitudes towards Pan-Africanism, and more particularly towards the federation of African states, have to be understood in relation to the very special conditions of the Horn of Africa. It will be necessary therefore to begin this survey with a few general remarks about the Somali Peninsula and the special characteristics of Somali nationalism. Before the partition of their grazing lands by Egypt, and later by France, Britain, Italy, and Ethiopia, in the latter part of the nineteenth century, the Somali did not constitute a single autonomous political unit. They were divided into a number of large and often hostile clans, themselves further split into a wide array of subsidiary kinship groups. And while wider ties were acknowledged, the individual's loyalties were most often focused upon the small 'blood compensation group' of kinsmen with whom he paid and received damages, which provided his main security in an extremely unfriendly environment. Within these small groups of kinsmen, usually only a few thousand strong, the rule of law applied in the sense that the elders had the power and the means to compose disputes. Outside these, however, there was no stable centralised authority to regulate the relations between opposed

SOMALI

groups. Yet there was a common code of morality recognised by all Somali, and a common tariff of damages and indemnities for wrongs. All disputes between rival groups could, when the parties were willing, be compounded by the payment of standard rates of compensation. There was thus a common code of, as it were, international law, and courts of arbitration could be mounted to judge between conflicting groups. There was also a common sentiment of Somali-ness, accompanied by a virtually uniform national Somali culture, and reinforced by the strong adherence of all Somali to Islam. Thus the Somali have always constituted a nation, but political nationalism was absent largely because of the divisive forces within

* Lecturer in Social Anthropology, University of Glasgow. This article is based on a paper read in January 1963 to the post-graduate seminar on Pan-Africanism and Eastern Africa at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

148

I. M. LEWIS

the nation; it was only after imperial partition that the way was opened towards the formation of a Somali nation-state.1 The division by non-Muslim colonial powers of the Somali Peninsula into French Somaliland, British Somaliland, the Ethiopian Haud and Ogaden, Italian Somalia, and Northern Province of Kenya,2 tended to reinforce Somali sentiments of national identity through Islam. This multiple colonisation of a single Muslim ethnic area brought the Somali as a single people into contact not only with three European governments, but also with the Egyptians and Ethiopians. No other ethnic groups were involved, except in French Somaliland, which the Somali shared with the ethnically related Danakil (or Afar); to assert their rights to independence the Somali therefore had no need to claim any other common feature than that of being Somali. There was no need in this situation, and indeed for long little inclination, to appeal to a wider identity as 'Africans'. Equally, the stereotype of the colonising power was not of a monolithic European or 'white' domination (as opposed to 'African' or 'black'), but of French, British, Ethiopians, and Italians, whose differences in national character and in systems of government were very obvious, and whose competition and rivalries the Somali were quick to exploit. Thus when between I900 and 1920 the famous Sayyid Mohammed 'Abdille Hassan (the so-called 'Mad Mullah') conducted his remarkable rebellion against the Christian colonisers (and particularly against Britain and Ethiopia), his appeal did not extend beyond the Somali as a national group.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PAN-SOMALI IDEAL3

The same is true of the main modern Somali nationalist movements, which have developed largely locally, out of touch with, and until recently little affected by, African nationalism elsewhere. From their inception these organisations have appealed to the common national identity of all Somali and have claimed the right to make their nation a nation-state. The Somali National League (S.N.L.), which had had an intermittent existence since 1935, emerged as a fully-fledged party in the

1 For fuller information on the structure of Somali traditional society see I. M. Lewis, A PastoralDemocracy (London, 1961). 2 The populations of these territories are approximately as follows: French Somaliland, 65,ooo (half of whom are Somali); Ethiopian Haud and Ogaden, 750,000 Somali; Somali Republic (Somalia and ex-British Somaliland), 2,250,000; Northern Province of Kenya, 200,000 Somali in a provincial population of 300,000. 3 For further information on Somali nationalism see I. M. Lewis, 'Modern Political Movements in Somaliland', in Africa, xxvIII (London, 1958), pp. 244-6I and 344-64; no. A. A. Castagno, 'Somalia', International Conciliation, 522 (New York, I959).

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PAN-AFRICANISM

AND

PAN-SOMALISM

I49

British Protectorate in I951 with the following programme: I. To work for the unification of the Somali people and territories. 2. To work for the advancement of the Somali by abolishing clan fanaticism and encouraging brotherly relations among Somalis. 3. To encourage the spread of education and the economic and political development of the country. 4. To co-operate with the British Government or any other local body whose aims are the welfare of the inhabitants of the country. Similarly, the Somali Youth League (S.Y.L.), founded as a youth club in British-occupied Somalia in I943, and fully organised as a party by the end of 1947, sought: i. To unite all Somalis generally and the youth especially, with the consequent repudiation of all harmful old prejudices, such for example as tribal distinctions. 2. To educate the youth in modern civilisation by means of schools and by cultural and propaganda circles. 3. To take an interest in and assist in eliminating by constitutional and legal means any existing or future situations which might be prejudicial to the interests of the Somalis. 4. To develop a Somali language, and to assist in putting into use among the Somalis the already existing writing known as Ismaniya. Here also it is Somali nationhood that is stressed and there is no reference to wider African issues. The paramount importance which the S.Y.L. attached at this early period to the Pan-Somali ideal was made even more explicit by the party's representatives to the FourPower Commission which visited Somalia early in I948 to examine Somali aspirations for the future. On that occasion the S.Y.L. stated that: 'The union of Italian Somaliland with the other Somalilands was their primary objective, for which they were prepared to sacrifice any other demand standing in the way of the achievement of Greater Somalia.' 1 This aim of the amalgamation of all the Somali territories, translating cultural nationalism into political nationalism, remains the basic credo common to all the nationalist parties. Such differences as exist on this issue, and they are slight, refer merely to the means by which Pan-Somalism should be achieved.2

1 Report the Four Power Commission of (London, I949), II, pp. IO-I I. The members were Britain, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union. 2 At the present time, the Greater Somalia League (G.S.L.) and the Somali National League are probably the most militant; and the Independent Constitutional Party (H.D.M.S.) -which draws its support almost entirely from the area between the Juba and Shebelle rivers-the least militant.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I50

I. M. LEWIS

When the S.Y.L. were returned to power in Somalia in 1956 as the first Somali government, with control only in internal affairs,the Prime Minister Abdullahi 'Ise, in his policy statement before the Assembly, assigned first place to the resolution of his country's border dispute with Ethiopia, but did not otherwise refer to his party's Pan-Somali aims. Three years later, however, when performing the same task on 26 July I959, with independence close at hand and the Greater Somalia League to contend with, Abdullahi 'Ise gave firstplace to the unification of the Somali territories. 'The Somali', he told the Assembly, 'form a single race, practise the same religion and speak a single language. They inhabit a vast territory which, in its turn, constitutes a welldefined geographic unit. All must know that the Government of Somalia will strive its utmost with the legal and peaceful means which are its democratic prerogative to attain this end: the union of Somalis, until all Somali form a single Great Somalia.'l With the approach of independence there was now a growing awareness amongst political leaders of the importance of forming links with the already independent African States with whom Somalia would soon have direct relations. This is evident in the charter of the National Pan-Somali Movement, an organisation founded at Mogadishu a month after the formation of the new government. Including representatives of the S.Y.L., the S.N.L. from British Somaliland, the Union somalifrom French Somaliland,2 and delegates also from democratique the Ethiopian Ogaden and the Northern Province of Kenya, the Movement expressed its primary aim, for the unity and independence of all Somali territoriesby peaceful and legal means, in much the same terms as the Prime Minister. But it set this in a wider context, seeking also 'to institute and maintain firm ties with the other peoples of the African continent and to maintain and reinforce relations with the states of the Islamic world'.3 It was in this spirit that the Minister charged with the responsibility of preparing the new State's constitution, one of the most pressingtasks facing Abdullahi 'Ise's government,4 was despatched in December to

1 II Corriere della Somalia, 27 July I959. 2 The situation in French Somaliland, still an oversea territory of France and currently seeking independence within the French community, is regarded by Somali nationalists as indentical with that in Algeria prior to Algerian independence. 3 II Corriere della Somalia, 3I August 1959. 4 The preparation of the constitution was initiated by a decree of 6 September 1957, which provided for the setting up of two committees, one political and the other technical. In the preparation of the final draft presented to the Assembly all the main political parties participated. See G. A. Costanzo, Problemicostituzionalidella Somalia nella preparazioneall' independenza (Milan, I962).

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PAN-AFRICANISM

AND

PAN-SOMALISM

I5I

visit Nigeria, Ghana, Guinea, and Liberia, to discover what could be learnt from the constitutional experience of these States. On President Nkrumah's suggestion, the constitution was drafted to include provisions for the eventual amalgamation of the other Somali territories. In its final version, accepted by the Assembly, the constitution faithfully reflects the new trend towards viewing the Pan-Somali ideal in a wider African context. Article VI (para. 4) states: 'The Somali Republic shall promote, by legal and peaceful means, the union of Somali territories and encourage solidarity among the peoples of the world, and in particular among African and Islamic peoples.' With this constitutional pledge to uphold, the British Protectorate and the former Italian Somalia united on I July I960, as a unitary Republic with a coalition government formed from the separate administrations of the two component countries. The disadvantageous position of this new African State has been most eloquently described by the present Prime Minister, Dr Abdirashid 'Ali Shirmarke: Our misfortune is that our neighbouring countries, with whom, like the rest of Africa, we seek to promote constructive and harmonious relations, are not our neighbours. Our neighbours are our Somali kinsmen whose citizenship has been falsified by indiscriminate boundary 'arrangements'. They have to move across artificial frontiers to their pasturelands. They occupy the same terrain and pursue the same pastoral economy as ourselves. We speak the same language. We share the same creed, the same culture and the same traditions. How can we regard our brothers as foreigners? ... Of course, we all have a strong and very natural desire to be united. The first step was taken in I960 when the Somaliland Protectorate was united with Somalia. This act was not an act of 'colonialism' or 'expansionism' or 'annexation'. It was a positive contribution to peace and unity in Africa and was made possible by the application of the principle of the right to self-determination.1 Here we see the view that Pan-Somalism is not merely not incompatible with Pan-Africanism, but is in fact a positive contribution towards PanAfrican unity.

RELATIONS WITH OTHER AFRICAN STATES

Before examining how, since independence, the Somali Government has developed this view and sought to gain support for it among African States, it will be convenient to consider the relations between Ethiopia and the Somali Republic, since Ethiopia's position is a crucial factor in any further implementation of the Pan-Somali ideal.

1 The Somali Peninsula: a new light on imperialmotives(London, 1962), p. vi.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I52

I. M. LEWIS

Ethiopia has consistentlyopposed the union of the Somali territories, advocating instead federation with herself.' Thus the Ethiopian Government sought to prevent the union of the British Protectorate with Somalia, protesting to the British Government after Mr LennoxBoyd's announcement at Hargeisa in February 1959 that, should the Protectorate Legislative Council desire closer associationwith Somalia, his government would arrange the necessary negotiations. This was hardly a propitious start to amicable relations between Ethiopia and the Republic. But it was of course merely a symptom of the fundamental issue. This arises from the fact that perhaps as many as three-quartersof a million Somalis live in the Haud and Ogaden, regions which are administered by Ethiopia, but which have no mutually agreed frontier with the Somali Republic and which are, moreover, claimed by the Republic. 'Claimed' is perhaps too strong an expression. The present demand is, more specifically, the right of self-determination for all Somalis. On attaining independence, the Somali Republic not only inherited the old Italo-Ethiopian border dispute on which so much has been written,2 but was also pledged by its constitution, and obliged by popular sentiment, to bring into the Republic the Somalis in the Ogaden region and to recover the western Haud, which Britain had relinquished to Ethiopia on the dubious basis of the Anglo-Ethiopian treaty of I897.3 In practice, since independence both sides have observed the pre-existing frontiers. Relations between the two States, however, have been anything but friendly, and Ethiopia is concerned not merely with retaining her Somali regions, but also with French

1 As for example in the Emperor's speech at Gabradare in the Ogaden in August I956, when he spoke of the racial, economic, and geographic unity of the Somali and Ethiopian peoples. This speech, of course, was vigorously repudiated in Somalia. 2 See, for example, The Somali Peninsula,pp. 59-60 and 63-77; A. A. Castagno, op. cit. FrontierProblem(Ministry of Information, Addis Ababa, pp. 386-91; and The Ethio-Somalia I96I). 3 This treaty, signed by Britain with Ethiopia after the battle of Adowa and in the context of Anglo-French rivalry on the Nile, was designed to secure Ethiopian goodwill and to gain some assurance that Ethiopia would not support the Mahdist rebels in the Sudan. Despite the fact that the Anglo-Somali treaties of I884-6, on the basis of which the British Somaliland Protectorate was established, pledged Britain to protect the 'independence' of the Somali clans concerned, by the treaty of I897 Britain unilaterally abandoned many of the clansmen she had undertaken to 'protect' and some 67,000 square miles of territory were excised from the Protectorate. This is the vital grazing area known as the western Haud. However, the treaty was cleverly worded to stipulate that while Ethiopia recognised British sovereignty within the new frontiers of the Protectorate, Britain did not reciprocally recognise Ethiopian sovereignty over the land and people who had been abandoned. Yet it was on this questionable basis, admittedly with reluctance, that in I954 Britain finally surrendered the area to Ethiopian administration-again without consultation with the Somali contracting parties of I884 and i886.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PAN-AFRICANISM

AND

PAN-SOMALISM

I 53

Somaliland, where she is deeply committed through her virtual control of the railway line from Addis Ababa to Jibuti. Following the Somali Republic's emergence as an independent State on I July 1960, the Ethiopians strengthened their military garrisons in the disputed Haud and Reserved Areas. The end of the year was marked by a number of incidents, of which the most serious occurred at Danod, on the Ethiopian side, 85 miles south of the def.actofrontier. The refusal of the Ethiopian authorities to allow a party of nomads from the Republic to draw water from the Danod water-holes led to a tribal skirmish in the area, which was suppressed by Ethiopian ground and air forces.1 This and other similar incidents led the Somali Government to protest strongly to the Ethiopian Government, and the situation was also brought to the attention of the United Nations. Throughout 1961 these strained relations continued, the highlight being an exchange of diplomatic Notes when the Ethiopian Government charged the Republic with conducting an unfriendly campaign. And although Ethiopia supplied generous aid to the Republic after the flood damage at the end of the year, the cold war between the two States continued to gather momentum throughout 1962.2 As will be seen presently, the recent heightening of tension between Ethiopia and the Republic is associated with the approaching independence of Kenya as it affects Somali aspirations for the union of the Northern Frontier District (N.F.D.) with the Republic. A referendum was held in June 1961 to seek national approval for the constitution, which had been passed by the Somali Assembly prior to the union of the two parts of the Republic; and on 19 August, Dr Shirmarke, Prime Minister since independence, told the National Assembly: While acknowledging its traditional friendly ties, the Somali Republic wishes to establish relations with the largest possible number of independent countries and to remain outside any bloc or political coalition, thus confirming

1 See The DanodIncidents,a pamphlet published by the Somali Republic Ministry of the Interior in 1961. 2 In April I962, the Somali Foreign Minister warned the U. N. Acting Secretary-General that current Ethiopian postures constituted a threat to peace. In September, an Ethiopian spy-ring was uncovered in the Northern Regions and was alleged to have been sent there to stir up trouble at the time of the President of the Republic's visit. In the same month, the Ethiopian Government withdrew diplomatic recognition from an official of the Somali embassy in Addis Ababa, and a wrangle developed about his nationality. In September also the government paper The Somali News attacked the United States for giving military aid to Ethiopia, and claimed that a jet airfield was being built at Gabradare in the Ogaden to menace the Republic. In October, the Ethiopian Government claimed that the representatives of io 'tribes' from the Republic had sought Ethiopian nationality. II

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

154

I.

M. LEWIS

as the goals of its international activity the maintenance of peace, respect for the neutrality principle, co-operation and solidarity among countries, and in particular among the African and Muslim nations. It [i.e. the new Government] always places above all, not only in thought but also in action, the intention of achieving the unification of the Somali territories by legal and pacific means.1 It was in this spirit that Somali delegations had already attended the third All-African People's Conference at Cairo in March 196I, and the Monrovia Conference in May. The previous meeting of the A.A.P.C. at Tunis in January I960 had passed a resolution on Somaliland approving the Pan-Somali aim; but at the March 1961 meeting the combined S.Y.L., S.N.L., and G.S.L. Somali delegation encountered serious opposition, and their protests that a resolution on this subject, passed during the proceedings, had been omitted from the final statement led to a walk-out by the Ethiopian delegation. At the Monrovia Conference, in which again both the Republic and Ethiopia participated, all that was achieved was a resolution urging the two States to settle their border disputes. At the Belgrade Conference in September, the President of the Republic took the opportunity of again stating his country's cause, but without attracting any tangible support. In October 1961, the Somali President, Adan Abdulla, went on a state visit to Ghana, the first African State south of the Sahara to establish diplomatic relations with the Republic. At the end of his stay he and President Nkrumah issued a joint communique, in which they expressed the view that 'outstanding frontier problems inherited from colonial regimes' could be solved by federation. They also recognised, however, 'the imperative need to restore the ethnic, cultural, and economic links arbitrarily destroyed by colonisation'. 2 In the same month, at the sixteenth session of the U.N. General Assembly, the Republic's Foreign Minister, Abdullahi 'Ise, stated: 'The Somali Government and the Somali people want the unification of Somalis in a single national entity to be obtained by peaceful and legal means.'3 Meanwhile, events in Kenya had led to increasing activity by the Somali political parties of the Northern Frontier District, and their demands for secession from Kenya and union with the Republic were given wide publicity in the Republic.4 The Northern

1 The SomaliNews, 25 August I96I.

Ibid. 27 October 1961. 3 Ibid. 13 October I961. 4 See, for example, The Somali News, 1961 and 1962, passim. See also A People in Isolation: FrontierDistrict of Kenya unionwith the SomaliRepublic a call bypoliticalpartiesof the Northern for (London, I962), a pamphlet published in connexion with the Kenya Conference.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PAN-AFRICANISM

AND

PAN-SOMALISM

155

Frontier District, covering an area of I02,000 square miles, is in fact a Province and comprises six administrative Districts: Garissa, Wajir, Mandera, Moyale, Marsabit, and Isiolo. The Somali, estimated to number about 2o0,ooo in the latest census returns, are mainly concentrated in the east of the N.F.D. in Garissa, Wajir, and Mandera Districts. The majority of the Somali entered this area by migration from the north within the last hundred years, although some Somali groups entered the area earlier and appear to have been its first known inhabitants. This Hamitic migration displaced groups of the north-east coastal Bantu-known to the early Arab geographers as the 'Zengi'also intruders, who had expanded into this area and Jubaland from the south. In response to approaches from the Somali N.F.D. parties in Kenya (particularly the People's Progressive Party led by 'Ali Aden Lord), the Somali National Assembly in November passed a motion in support of the union of the Province with the Republic, urging the Government to press for self-determination for its people. As a result, the Somali Government was now being forced to concentrate its Pan-Somali endeavour on the demands of a national minority in Kenya, a course bound to lead to conflict with the Kenyan nationalists as well as with Ethiopia, and likely to increase the Republic's difficulties in finding Pan-African support for her aims. Indeed, in October Tom Mboya of K.A.N.U. had visited Addis Ababa and, after an audience with the Emperor, announced that his party would categorically oppose all attempts at secession on the part of the peoples of the N.F.D.1 The next Pan-African meeting was the Lagos Summit Conference in January 1962, which the Republic attended with some misgivings over the exclusion of Algeria, whose provisional government it had recognised. On his return from Lagos, the Prime Minister announced that the Conference had agreed to set up an independent body to deal with disputes between African States, to which the Republic's difficulties with neighbouring States could be referred.2 In February, however, the Pan-African Freedom Movement for East and Central Africa, meeting at Addis Ababa, suggested that a solution could be found in federalism, and proposed an East African Federation of Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, and Zanzibar, with Ethiopia and the Somali Republic. To this end both Ethiopia and the Republic were urged to open negotiations

Mboya argued that Kenya had as legitimate a claim to Jubaland, which Britain had excised from Kenya and given to Italy to add to Somalia in 1925. These statements were attacked in an editorial in The Somali News, 20 October 1961, and in a letter from the Secretary-General of the S.Y.L. to The East AfricanStandard, October 196I. 30 2 The Somali News, I February 1962.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I56

I. M. LEWIS

for the extension of common services with the East Africa High Commission. The projected federation was to be achieved within the framework of the All-African People's Conference, and the leader of the Somali delegation took the opportunity of urging P.A.F.M.E.C.A. to use its influence to bring about a union of the Monrovia and Casablanca powers. The Pan-Somali goal was now seen in a wider-East African-context. Immediately following the P.A.F.M.E.C.A. meeting, and just before the Lancaster House Conference on Kenya, the Somali embassy in London issued a statement stressing that African unity and Somali unity were 'complementary' and that the Somali people, whose unity was based on common cultural, ethnic, and religious ties, had as pastoralists special problems which were best understood and catered for by a democratic Somali government.1 The Somali Government was not of course represented at the Kenya Conference, but it assisted the N.F.D. delegation in publicising their demands for secession from Kenya and union with the Republic. In the Republic itself there were widespread demonstrations in support of the Kenya secessionists. And in March the Prime Minister made a strongly anti-imperialist speech, attacking Ethiopia and France, and warning the British Government that it would be held responsible if the 'mistakes' of the past were added to and the inhabitants of the N.F.D. were refused the right 'to freely decide their own destiny'.2 At this time, relations between Ethiopia and the Republic were particularly hostile and both sides were engaged in a vituperative campaign by press and radio, the Somali Government being particularly anxious to deny that its support for the N.F.D. secessionists was delaying Kenya's independence, or was in any sense detrimental to the cause of African unity. The Somali News summed up the Somali point of view in the phrase 'Pan-Somalism is Pan-Africanism'; and the depth of feeling in the Republic at this time can be gauged from the fact that 31 members of the National Assembly chose this moment to table a motion of no confidence in the government, one of their specific criticisms being 'lack of courage' on the Pan-Somali issue. In replying to the motion, which was defeated by a considerable majority, the Prime Minister re-affirmed his government's dedication to the Belgrade principles of non-alignment, to the promotion of solidarity between

1 On the same occasion the Somali embassy in London distributed copies of The Somali Peninsula: a new light on imperialmotives,an important contribution to the history of the imperial partition of the Horn of Africa. 2 The Somali News, 23 March I962.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PAN-AFRICANISM

AND

PAN-SOMALISM

I57

peoples (particularly Africans and Muslims), and to the continuing struggle for Somali unification.1 Meanwhile, despite the K.A.D.U. and K.A.N.U. opposition to the secession of the Northern Frontier District, the British Colonial Secretary had announced that his government would appoint an independent commission 'to ascertainpublic opinion in the area regardingits future'. This news was received cautiously in the Republic. On 12 April, at a mass rally held to mark African solidarity week, the Prime Minister, after recalling the Republic's moral support for the national struggle in the Congo, Angola, Algeria, and South Africa,2 said that the announcement of the N.F.D. Commission was not satisfactorysince 'it was not clear whether the right of self-determination would be given to the people concerned'.3 However, the Republic demonstrated the genuineness of its desire to participate in an East African federation by acting upon the suggestion made at the P.A.F.M.E.C.A. conference, and sending observersto the meeting of the East African Central Legislative Assembly which followed.4 While maintaining the view that the responsibility of deciding the future status of the N.F.D. lay with Britain, the Government of the Republic also sought to promote better relations with the Kenya African leaders.5 Accordingly, K.A.N.U. was invited to send delegates to the Republic's Independence Day celebrations on I July. These were in fact attended by Jomo Kenyatta's daughter, by the party's Vice President, Oginga Odinga, and by others. Kenyatta himself and other K.A.N.U. delegates came later for a short visit, and this was followed by a six-day visit by Ronald Ngala and members of K.A.D.U. Both leaders were treated with full honours.6 Jomo Kenyatta in numerous discussions and speeches made it clear

1 The SomaliNews, 6 and 20 April 1962. In March I962, legislation banned trade with South Africa, refused transit to South African nationals, and closed sea and air ports to South African vessels or aircraft, save in case of emergency. 3 The SomaliNews, 20 April I962. 4 In June 1962, the Republic was represented at the Lagos Conference of Foreign Ministers, which approved a revised draft charter for the Organisation of African States. In his address, the Foreign Minister regretted the absence of a number of African States and stressed that his government was opposed to rival political groupings amongst the African States. The Republic was also represented in June at the Islamic World Conference in Baghdad, which passed a resolution supporting the Somali struggle for union. 5 This was partly, apparently, in response to representations made by the British Government, which urged that a final settlement of the N.F.D. problem would have to be acceptable to Kenya's African leaders. 6 Both were accorded the Freedom of Mogadishu and awarded the Star of Somali Solidarity. For details of these visits, see The Somali Republicand African Unity, a pamphlet published by the Somali Government in September I962.

2

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I58

I. M. LEWIS

that he regarded the N.F.D. as an inalienable part of Kenya, and was not to be moved on the Somali issue. After his visit, the Somali Minister of Information held a press conference, at which he clarified his government's position, emphasising that a federation of East and Central African States was 'an absolute necessity', but that it would have to be designed so that the Somali people formed a single unit within it. There was no question, however, of his government forcing Somalis under alien rule to unite. Unity could only be based upon the principle of self-determination. And notwithstanding his government's earlier reservations, the Minister made it clear that they now welcomed the British Government's decision to send a commission to the N.F.D. The Republic, he stated, would not object if the commission found that a majority of the peoples of the Province wished to remain with Kenya. But if majorityfeeling ran the other way, his government insisted that secession should be granted before Kenya's independence. This was necessary in view of the impending East African federation; and the time for settling boundaries was before, not after federation.1 The Minister also challenged Kenyatta's references to the N.F.D. as 'part and parcel' of Kenya, and referred to the different way of life of its inhabitants, its isolation, and the special administrative arrangements which had been employed in running it. Finally, the Minister reiterated his government's view that the settlement of the problem was the responsibility of the British Government, and that the Somali Republic was the only African state with a 'legitimate interest' in it. No headway had been made with Kenyatta, although Ngala, as might have been expected with his party's regionalist policy, appeared to be more flexible. But nothing tangible was achieved in the course of these visits, and after the K.A.N.U. and K.A.D.U. delegations had departed the Government settled down to await the N.F.D. Commission and its findings, keeping meanwhile a watching brief on events in the area. In the middle of October, the two-man Commission eventually arrived, and a month later had completed its work.2 It found that the vast majority of the Somali of the Province desired secession and union with the Republic, as did most of the Muslim Galla and some other minor groups. Despite these quite unequivocal findings, the new constitutional

1 Here the Minister referred to his country's unhappy experience in trying to settle its boundary dispute with Ethiopia. 'The settlement of boundaries', he said, 'can be one of the most intractable problems between independent African States.' 2 The Commission consisted of Major General M. P. Bogert from Canada, and Mr G. M. Onyiuke, Director of Public Prosecutions in Eastern Nigeria. Their findings were FrontierDistrict Commission published as Reportof the Northern (London, 1963), Cmnd. 1900.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PAN-AFRICANISM

AND

PAN-SOMALISM

159

arrangements for Kenya announced in March 1963 by the British Colonial Secretary provided only for the creation of a new seventh region embracing the predominantly Somali areas of the N.F.D. This decision, interpreted as precluding the possibility of subsequent Somali secession, was received with anger and resentment in the District and in the Republic. Indeed, to mark the extent of popular feeling, the government of the Republic was forced, not without reluctance, to break off diplomatic relations with Britain; and the Somali Chiefs and local authorities in the District refused to co-operate with the Kenya administration or to participate in the elections. To many Somali, this unhappy compromise is viewed as a further injury in the long tradition of British disregard for Somali interests which began with the unfortunate Anglo-Ethiopian treaty of 1897.

Somali nationalism began as an exclusive movement aimed at the amalgamation of the Somali territories in the Horn of Africa, such wider interests as it possessed being directed more towards the Muslim nations of the world than towards the African States. In the last few years, and particularly since independence, Somali nationalists have evinced a growing concern with both African and world affairs, while still retaining their Islamic ties.1 The present Government has maintained a position of strict non-alignment and at the same time has also sought to play an active, if modest role in Pan-African affairs. Pan-Somalism, based on the principle of self-determination, is now viewed as a positive contribution towards African unity, of which the first step has already been achieved by the creation of the Somali Republic. This, of course, was a union by mutual consent of two separate, independent States, and the addition of French Somaliland, in spite of Ethiopia's objections, would merely be an extension of this. Where the Pan-Somali aim encounters serious constitutional as well as political difficulties is with the Somali territories in Ethiopia and Kenya, for here the application of the right of self-determination to the Somali peoples concerned is in conflict with the principle of territorial sovereignty. It is hardly surprising therefore, notwithstanding the special circumstances of the Somali case, that both K.A.N.U. and K.A.D.U. in Kenya, as well as Ethiopia, should oppose the Somali aim. Somali nationalists, however, can with justice protest that their

1 The Republic has diplomatic relations with the following Muslim countries: Egypt, Lebanon, Sudan, Algeria, Pakistan, Syria, and Saudi Arabia.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I6o

I. M. LEWIS

aims are even here compatible with Pan-Africanism, and maintain that the unification of the Somali territories of Ethiopia and Kenya with the Republic would be the prelude to Somali participation in an East African federation. From this point of view, opposition to the association of the Somali territories is detrimental to Pan-Africanism, which, as President Adan Abdulla has warned, is in danger of being frustrated by 'the unwillingness of African rulers to curb their powers and to lift their artificial colonial boundaries'.1 Since the favourable resolution passed at the Tunis A.A.P.C. meeting in I96o, the Somali case has on the whole attracted little support from other African States. Those who have shown most sympathy are Egypt and Ghana, and of all the African States it is with Egypt that the Republic has closest ties and to which it is most indebted economically. Yet despite this, in the wider sphere of African affairs the Somali Government has not aligned itself particularly with these two States. Indeed, it is opposed to the Monrovia-Casablanca division; in so far as it takes sides it has tended, like Ethiopia, to follow Monrovia.2 But what is more significant, I think, is that Ethiopia and the Republic should so often speak with the same voice in African and world affairs, despite their very different systems of government, their religious differences, and their long history of conflict. This suggests that the resolution of the Somali unification problem by a federation including both Ethiopia and the Republic is not so fanciful as might at first appear. And, of course, more recently both States have participated in the P.A.F.M.E.C.A. negotiations in the Congo. In justly evaluating these considerations, however, attention must also be given to the Northern Frontier District issue. For if the Somali aim of secession from Kenya is not achieved it is difficult to see how co-operation can be maintained between the Republic and Ethiopia and Kenya. Finally, in tracing the development of Pan-African attitudes in the Republic, it is interesting to notice how the Somali approach to wider African unity has been influenced by the fact that Pan-Somalism is based upon ethnic and cultural homogeneity, coupled with the principle of self-determination. This has led Somali nationalists to emphasise the importance of such factors as a basis for African unification. These views were most pointedly expressed by the President of the Republic in his address on Pan-Africanism during the K.A.N.U. visit

1 In an important speech on Pan-Africanism at a state banquet held in honour of Jomo Kenyatta on 28 July I962. 2 It should be noted, however, that both Ethiopia and the Somali Republic attended the Belgrade Conference and were in fact the only States who had been at the Monrovia Conference to go to Belgrade.

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PAN-AFRICANISM

AND

PAN-SOMALISM

i6i

to the Republic. Referring to his country's experience since independence, the President said: We have learned of a cardinal principle underlying the effectiveness or otherwise of a political union between independent states. It is this: the ordinary person must be able to identify himself and his interests with the new order, on economic, ethnic, and cultural grounds. It is this lesson that is perhaps the hardest to learn, but if we Africans are proud to take our place as a democratic people in the comity of nations we must do more than pay lip-service to the feelings of the ordinary man and woman in our society.1 The special predicament of the Somali, then, remains that whereas other independent African States seek to make themselves into nations, they seek to build a State on the basis of their nationhood. And whatever the implications of this elsewhere, there seems little doubt that if Kenya and Ethiopia join an East African federation which excludes the Somali Republic, and perpetuates the partition of the Somali people, unrest and instability will be entrenched in the Horn of Africa. The sacrifice of national pride and territorial sovereignty which would be involved in including the Somali as a unified territorial entity in an enlarged East African federation would surely be amply rewarded by the prospect of harmony between three, at least, of the member States.

1 Speech of 28 July I962. The President took a similar line in another speech on I6 August I 962, during Ronald Ngala's visit. On that occasion, speaking of democratic practice in the Republic, he regretted that many other African States 'because of the intolerances that are inevitable among a heterogeneous populace' had had to resort, for the sake of cohesion, to a single-party system of government. 'Others forbid politics altogether.'

This content downloaded on Fri, 25 Jan 2013 15:00:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Mental Colonized Nation Somalia 2 1 1Document5 pagesThe Mental Colonized Nation Somalia 2 1 1KhadarNo ratings yet

- The Ogaden and The Fragility of Somali Segmentary Nationalism By: I.M. LewisDocument8 pagesThe Ogaden and The Fragility of Somali Segmentary Nationalism By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Ohio Homeland Security Hls 0075 A Guide To Somali CultureDocument44 pagesOhio Homeland Security Hls 0075 A Guide To Somali CultureSFLD0% (1)

- The Somali Conquest of The Horn of Africa By: I.M. LewisDocument19 pagesThe Somali Conquest of The Horn of Africa By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (1)

- Scarcity and SurfeitDocument37 pagesScarcity and SurfeitMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- U.S. Strategic Interest in Somalia-From Cold War Era To War On Terror by Mohamed MohamedDocument86 pagesU.S. Strategic Interest in Somalia-From Cold War Era To War On Terror by Mohamed MohamedIsmael Houssein MahamoudNo ratings yet

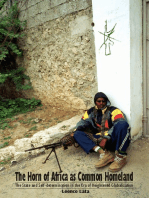

- The Horn of Africa as Common Homeland: The State and Self-Determination in the Era of Heightened GlobalizationFrom EverandThe Horn of Africa as Common Homeland: The State and Self-Determination in the Era of Heightened GlobalizationNo ratings yet

- A Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of AfricaFrom EverandA Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of AfricaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Collapse of The Somali State - The Impact of The Colonial Legacy PDFDocument187 pagesThe Collapse of The Somali State - The Impact of The Colonial Legacy PDFChina BallNo ratings yet

- The Last Century and The History of SomaliaDocument154 pagesThe Last Century and The History of SomaliaNathan Hale100% (3)

- Somali Identity ArticleDocument53 pagesSomali Identity ArticleetrixiNo ratings yet

- The Application of Sharia in SomaliaDocument6 pagesThe Application of Sharia in SomaliaDr. Abdurahman M. Abdullahi ( baadiyow)No ratings yet

- Clanship and Contract in Northern Somaliland By: I.M. LewisDocument21 pagesClanship and Contract in Northern Somaliland By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (2)

- Force and Fission in Northern Somali Lineage Structure By: I.M. LewisDocument20 pagesForce and Fission in Northern Somali Lineage Structure By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Somalia - The Untold Story Through Eyes OfwomenDocument270 pagesSomalia - The Untold Story Through Eyes Ofwomenrostad12100% (1)

- DR - Ali Mohamed Ali Iye Wrote The History of Daarood ClanDocument15 pagesDR - Ali Mohamed Ali Iye Wrote The History of Daarood ClanDrAli Mohamed Ali Iye100% (1)

- The Ogaden A Microcosm of Global ConflictDocument20 pagesThe Ogaden A Microcosm of Global ConflictIbrahim Abdi GeeleNo ratings yet

- Somalia 1900 - 2000Document19 pagesSomalia 1900 - 2000whvn_havenNo ratings yet

- Aman, The Story of A Somali Girl Book ReviewDocument3 pagesAman, The Story of A Somali Girl Book ReviewJsea2011No ratings yet

- The Total Somali Clan Genealogy (Second Edition) : African Studies Centre Leiden, The NetherlandsDocument54 pagesThe Total Somali Clan Genealogy (Second Edition) : African Studies Centre Leiden, The NetherlandsibrahimNo ratings yet

- The Interval Battle of DayniileDocument15 pagesThe Interval Battle of DayniileBinyamine MujahidNo ratings yet

- Somalia HistoryDocument21 pagesSomalia HistoryAuntie DogmaNo ratings yet

- The Isaq Somali Diaspora and Pol2013Document26 pagesThe Isaq Somali Diaspora and Pol2013Khadar Hayaan Freelancer100% (2)

- 1961 Somaliland's Last Year As A ProtectorateDocument13 pages1961 Somaliland's Last Year As A ProtectorateAbdirahman AbshirNo ratings yet

- The Wallaga MassacreDocument6 pagesThe Wallaga MassacreIbrahim Abdi GeeleNo ratings yet

- COLONIAL RULE IN THE BRITISH SOMALILAND PROTECTORATE, 1905-1939 by PATRICK KITABURAZA KAKWENZIRE (PHD) Vol. 1 of 2Document294 pagesCOLONIAL RULE IN THE BRITISH SOMALILAND PROTECTORATE, 1905-1939 by PATRICK KITABURAZA KAKWENZIRE (PHD) Vol. 1 of 2AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (5)

- Tareke Ethiopia Somalia War of 1977Document34 pagesTareke Ethiopia Somalia War of 1977DayyanealosNo ratings yet

- AbanegaDocument7 pagesAbanegaWeldeseNo ratings yet

- Out of Mogadishu - Yusuf HaidDocument129 pagesOut of Mogadishu - Yusuf Haidmaxamed muuseNo ratings yet

- 180638Document19 pages180638WadaayNo ratings yet

- The Somali Conflict: Prospects For PeaceDocument14 pagesThe Somali Conflict: Prospects For PeaceOxfam100% (1)

- Phonology of The OrmaDocument39 pagesPhonology of The OrmasemabayNo ratings yet

- Imperial Policies and Nationalism in The Decolonization of SomalilandDocument28 pagesImperial Policies and Nationalism in The Decolonization of SomalilandahmedNo ratings yet

- Islam in Somali HistoryDocument16 pagesIslam in Somali HistoryIbrahim Abdi Geele100% (4)

- Colonial Policies and The FailureDocument182 pagesColonial Policies and The FailureIbrahim Abdi Geele100% (2)

- Fulani Empire of SokotoDocument260 pagesFulani Empire of Sokotouzbeg_khan100% (1)

- Sufism in Somaliland A Study in Tribal Islam - I By: I.M. LewisDocument23 pagesSufism in Somaliland A Study in Tribal Islam - I By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (1)

- The Somali PeninsulaDocument104 pagesThe Somali Peninsulamjplayer201067% (3)

- History of Southern Africa NotesDocument104 pagesHistory of Southern Africa NotesHomok NokiNo ratings yet

- U.S. Foreign Assistance To Somalia - Phoenix From The AshesDocument26 pagesU.S. Foreign Assistance To Somalia - Phoenix From The AshessaidbileNo ratings yet

- The Cult of Muslim Saints in Harar - Religious Dimension - Foucher PDFDocument12 pagesThe Cult of Muslim Saints in Harar - Religious Dimension - Foucher PDFmohamed abdirahmanNo ratings yet

- The Bantu Jareer Somalis Unearthing AparDocument317 pagesThe Bantu Jareer Somalis Unearthing Aparлюбовь ивановаNo ratings yet

- The So-Called 'Galla Graves' of Northern Somaliland By: I.M. LewisDocument5 pagesThe So-Called 'Galla Graves' of Northern Somaliland By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (3)

- Giib 1 PDFDocument6 pagesGiib 1 PDFRashid JamaNo ratings yet

- Colonial Concubinage in Eritrea, 1890S1941Document85 pagesColonial Concubinage in Eritrea, 1890S1941Jeff Cassiel100% (1)

- The Gadabursi Somali ScriptDocument24 pagesThe Gadabursi Somali Scriptnewwaver203239100% (5)

- History of SomaliaDocument18 pagesHistory of Somaliashimbir100% (4)

- The So-Called 'Galla Graves' of Northern SomalilandDocument5 pagesThe So-Called 'Galla Graves' of Northern SomalilandAchamyeleh TamiruNo ratings yet

- Misunderstanding The Somali Crisis By: I.M. LewisDocument4 pagesMisunderstanding The Somali Crisis By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Recovering The Somali State: The Islamic FactorDocument36 pagesRecovering The Somali State: The Islamic FactorDr. Abdurahman M. Abdullahi ( baadiyow)No ratings yet

- Haweenku Wa Garab (Women Are A Force) - Women and The Somali Natio - PDF Version 1Document22 pagesHaweenku Wa Garab (Women Are A Force) - Women and The Somali Natio - PDF Version 1ApdiKaaFi AhmedNo ratings yet

- The Fulani Empire of SokotoDocument260 pagesThe Fulani Empire of Sokotoabaye2013No ratings yet

- (Mohamed Haji Mukhtar) Historical Dictionary of So (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFDocument401 pages(Mohamed Haji Mukhtar) Historical Dictionary of So (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFFüleki Eszter67% (3)

- Gene OlogiesDocument97 pagesGene OlogiesNoah MohamedNo ratings yet

- DERG. A Short HistoryDocument10 pagesDERG. A Short HistoryXINKIANGNo ratings yet

- The Darwish Resistance: The Clash Between Somali Clanship and State SystemDocument18 pagesThe Darwish Resistance: The Clash Between Somali Clanship and State Systembinsalwe100% (1)

- Somaliland Country Report Mark Bradbury PDFDocument60 pagesSomaliland Country Report Mark Bradbury PDFMohamed AliNo ratings yet

- Yurugu An African Centered Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behavior Marimba Ani SmallerDocument337 pagesYurugu An African Centered Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behavior Marimba Ani Smallerbingiedred98% (47)

- Domestic Slavery in 18th and Early 19th Century North Sudan MA Thesis (1992)Document241 pagesDomestic Slavery in 18th and Early 19th Century North Sudan MA Thesis (1992)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Diamonds - Michael ODonohue Chapter 1 of 2 PDFDocument26 pagesDiamonds - Michael ODonohue Chapter 1 of 2 PDFAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- THE HEART OF THE MATTER SIERRA LEONE, DIAMONDS & HUMAN SECURITY (2000) Economic / Historic ReportDocument99 pagesTHE HEART OF THE MATTER SIERRA LEONE, DIAMONDS & HUMAN SECURITY (2000) Economic / Historic ReportAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Views of Ancient Egypt Since Napolean Boneparte: Imperialism, Colonialism, and Modern Appropriations (2003) UCL PressDocument119 pagesViews of Ancient Egypt Since Napolean Boneparte: Imperialism, Colonialism, and Modern Appropriations (2003) UCL PressAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Asyut in The 1260s (1844-1853) - by Terrance WalzDocument14 pagesAsyut in The 1260s (1844-1853) - by Terrance WalzAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Islamic Roots of Capitalism, Egypt 1760-1840 - Peter Gran (1941) University of Texas PressDocument148 pagesIslamic Roots of Capitalism, Egypt 1760-1840 - Peter Gran (1941) University of Texas PressAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (1)

- Philosphy of History of Ibn Khaldun - by Muhsin Mahdi (1957) University of Chicago PressDocument158 pagesPhilosphy of History of Ibn Khaldun - by Muhsin Mahdi (1957) University of Chicago PressAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri50% (2)

- Indian Influences On Rastafarianism (2007) BA Thesis Univ OhioDocument53 pagesIndian Influences On Rastafarianism (2007) BA Thesis Univ OhioAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (1)

- Slaves and Slavery in Muslim Africa - John Ralph Willis. Vol.2 The Servile EstateDocument15 pagesSlaves and Slavery in Muslim Africa - John Ralph Willis. Vol.2 The Servile EstateAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Does Modernization Require Westernization? - Deepak Lal (2000) The Independant ReviewDocument21 pagesDoes Modernization Require Westernization? - Deepak Lal (2000) The Independant ReviewAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Keeping Ma'at: An Astronomical Approach To The Orientation of The Temples in Ancient Egypt - by Juan Antonio Belmonte and Mosalam Shaltout (2010)Document9 pagesKeeping Ma'at: An Astronomical Approach To The Orientation of The Temples in Ancient Egypt - by Juan Antonio Belmonte and Mosalam Shaltout (2010)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Unfer The Raj: Prostitution in Colonial Bengal - by Sumanta Banerjee (1998)Document26 pagesUnfer The Raj: Prostitution in Colonial Bengal - by Sumanta Banerjee (1998)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Nubians, Black Africans and The Development of Afro-Egyptian Culture in Cairo at The End of The Nineteenth Century - by Terence WalzDocument16 pagesNubians, Black Africans and The Development of Afro-Egyptian Culture in Cairo at The End of The Nineteenth Century - by Terence WalzAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- LIBYA, THE TRANS - SAHARAN TRADE OF EGYPT, AND ABDALLAH AL - KAHHAL, 1880-1914 - by Terence Walz in Islamic Africa Vol 1 Nol 1 2010Document23 pagesLIBYA, THE TRANS - SAHARAN TRADE OF EGYPT, AND ABDALLAH AL - KAHHAL, 1880-1914 - by Terence Walz in Islamic Africa Vol 1 Nol 1 2010AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri0% (1)

- Trans Saharan Migration and The Colonial Gaze The Nigerians in Egypt - Terence WalzDocument34 pagesTrans Saharan Migration and The Colonial Gaze The Nigerians in Egypt - Terence WalzAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Slave, Slave Trade and Abolition Attempts in Egypt and Sudan 1820-1882 (1981)Document139 pagesSlave, Slave Trade and Abolition Attempts in Egypt and Sudan 1820-1882 (1981)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (1)

- Sudanese Trade in Black Ivory: Opening Old WoundsDocument21 pagesSudanese Trade in Black Ivory: Opening Old WoundsAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (1)

- Islamic Law and and Slavery in Premodern West Africa- by Marta GARCIA NOVO Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Journal of World History Universitat Pompeu Fabra ا Barcelona Número 2 (novembre 2011)Document20 pagesIslamic Law and and Slavery in Premodern West Africa- by Marta GARCIA NOVO Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Journal of World History Universitat Pompeu Fabra ا Barcelona Número 2 (novembre 2011)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Nubians of Egypt and Sudan, Past and PresentDocument5 pagesNubians of Egypt and Sudan, Past and PresentJohanna Granville100% (5)

- Trade Between Egypt and Bilad Al-Takrur in 18th Century - by Terence WalzDocument35 pagesTrade Between Egypt and Bilad Al-Takrur in 18th Century - by Terence WalzAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Sexuality in The Age of Empire (2011)Document67 pagesSexuality in The Age of Empire (2011)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Linkages and Similarities Between Scholars and European Scholars PDFDocument26 pagesLinkages and Similarities Between Scholars and European Scholars PDFAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- The Decisive Criterion For Distinguishing Islam From Masked Infidelity - Imam Al Ghazali (English)Document30 pagesThe Decisive Criterion For Distinguishing Islam From Masked Infidelity - Imam Al Ghazali (English)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- The Radical Enlightenment: Pantheists, Freemasons, and Republicans (2006) by Margret C. JacobsDocument65 pagesThe Radical Enlightenment: Pantheists, Freemasons, and Republicans (2006) by Margret C. JacobsAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (2)

- Muslim Economic-16 PDFDocument215 pagesMuslim Economic-16 PDFAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Works On Market Supervision Andshar'iyah Governance (Al-Hisbah Waal-Siyasah Al-Shar'iyah) by The Sixteenthcentury Scholars PDFDocument10 pagesWorks On Market Supervision Andshar'iyah Governance (Al-Hisbah Waal-Siyasah Al-Shar'iyah) by The Sixteenthcentury Scholars PDFAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- The Decisive Criterion For Distinguishing Islam From Masked Infidelity - Imam Al Ghazali (English)Document30 pagesThe Decisive Criterion For Distinguishing Islam From Masked Infidelity - Imam Al Ghazali (English)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Islamic Distributive Scheme PDFDocument13 pagesIslamic Distributive Scheme PDFAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Economic and Financial Crises inFifteenth-Century Egypt - Lessons From The History PDFDocument23 pagesEconomic and Financial Crises inFifteenth-Century Egypt - Lessons From The History PDFAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Elements of StateDocument6 pagesElements of StateJesica Belo100% (1)

- Trips, Trims N UnctadDocument29 pagesTrips, Trims N UnctadAnand RaoNo ratings yet

- FMM Working Paper: What'S Wrong With Modern Money Theory (MMT) : A Critical PrimerDocument38 pagesFMM Working Paper: What'S Wrong With Modern Money Theory (MMT) : A Critical PrimerMark MacIntyreNo ratings yet

- Trancripts MOOC Classical Sociological TheoryDocument97 pagesTrancripts MOOC Classical Sociological TheoryHigoNo ratings yet

- Role of Pay CommissionDocument23 pagesRole of Pay Commissiondeepankarrao100% (2)

- Excelsior: DailyDocument12 pagesExcelsior: DailyAnil PeshinNo ratings yet

- WAC News Aug 2006Document4 pagesWAC News Aug 2006UN-HABITAT NepalNo ratings yet

- Chap1 Nature of Contract-IntroductionDocument11 pagesChap1 Nature of Contract-IntroductionjankiNo ratings yet

- Pre-Development Vs Post-Development Runoff Volume Analysis Jeffrey J. E A R H A R T, P.E., M.S., Dyer, Riddle, Mills & Precourt, IncDocument12 pagesPre-Development Vs Post-Development Runoff Volume Analysis Jeffrey J. E A R H A R T, P.E., M.S., Dyer, Riddle, Mills & Precourt, IncLeticia Karine Sanches BritoNo ratings yet

- Ca 8454Document4 pagesCa 8454bluerosedtu0% (1)

- Food Defense Program Security MeasuresDocument5 pagesFood Defense Program Security MeasuresgmbyNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia Powerplants Output Co2 and IntensityDocument5 pagesSaudi Arabia Powerplants Output Co2 and IntensityMahar Tahir Sattar MtsNo ratings yet

- Soci1002 Unit 8 - 20200828Document12 pagesSoci1002 Unit 8 - 20200828YvanNo ratings yet

- Sharica Marie Go-Tan Vs Spouses TanDocument2 pagesSharica Marie Go-Tan Vs Spouses Tanmerlyn gutierrezNo ratings yet

- Territorial and Extra Territorial Jurisdiction IPC PDFDocument14 pagesTerritorial and Extra Territorial Jurisdiction IPC PDFHarsh Vardhan Singh HvsNo ratings yet

- Sunace International Not Liable for Worker's Contract ExtensionDocument2 pagesSunace International Not Liable for Worker's Contract ExtensionPlaneteer Prana100% (1)

- Irll Ch-7: Industrial Disputes Resolution System Under The Industrial Disputes Act, 1947Document16 pagesIrll Ch-7: Industrial Disputes Resolution System Under The Industrial Disputes Act, 1947ayeshaNo ratings yet

- CLASS-PROGRAM-Grade-4-CATCH-UP FRIDAY-WITH ActivitiesDocument13 pagesCLASS-PROGRAM-Grade-4-CATCH-UP FRIDAY-WITH ActivitiesVenson AgonoyNo ratings yet

- Diversity Cultural Competence ChecklistDocument5 pagesDiversity Cultural Competence ChecklistMUHAMMAD ARIF HARJANTONo ratings yet

- Maglalang Vs CADocument2 pagesMaglalang Vs CACleinJonTiuNo ratings yet

- Election Law Class Notes 2020Document19 pagesElection Law Class Notes 2020Alianna Arnica MambataoNo ratings yet

- The Circular Economy Economic Managerial and Policy Implications - SpringerDocument191 pagesThe Circular Economy Economic Managerial and Policy Implications - SpringerDaniela perdompNo ratings yet

- Midterm Examination CSCDocument7 pagesMidterm Examination CSCAimee SalangNo ratings yet

- International Relations Theories ExplainedDocument13 pagesInternational Relations Theories ExplainedRashmi100% (1)

- Kenneth S. Greenberg-Nat Turner - A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory (2003)Document310 pagesKenneth S. Greenberg-Nat Turner - A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory (2003)Hego RoseNo ratings yet

- Dayton Reinsurance LetterDocument1 pageDayton Reinsurance LetterdhmontgomeryNo ratings yet

- Emilio A. Gonzales III vs. Office of The President, G.R. Nos. 196231 & 196232 September 4, 2012Document3 pagesEmilio A. Gonzales III vs. Office of The President, G.R. Nos. 196231 & 196232 September 4, 2012Kang MinheeNo ratings yet

- Meerut Conspiracy Case Judgement Volume IIDocument349 pagesMeerut Conspiracy Case Judgement Volume IISampath Bulusu100% (1)

- A Comparison of The Manual Electoral System and The Automated Electoral System in The PhilippinesDocument42 pagesA Comparison of The Manual Electoral System and The Automated Electoral System in The PhilippineschaynagirlNo ratings yet

- 2018 Dar Cancellation RulesDocument7 pages2018 Dar Cancellation RulesPhill Sean Recla100% (5)