Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and Vocabulary

Uploaded by

joabeilonOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and Vocabulary

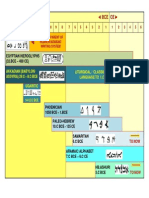

Uploaded by

joabeilonCopyright:

Available Formats

Study Guide for Students of Beginning Biblical Hebrew/Aramaic From Letters, Vowels & Syllables to New Vocabulary Joab

Eichenberg-Eilon, PhD A. Learning Hebrew Letters and Vowels Hebrew Letters 1. For Biblical Hebrew, the most important skill is decoding. Decoding means identifying letters and vowels and instantly knowing what sounds they produce. Writing them and actually pronouncing them, let alone identifying the letters and vowels by listening to the sounds are nice skills to have, but they are secondary. 2. In the document library you will find several charts for learning the alphabet as well as a document with ready-to-print flash cards of all the Hebrew letters. If this is your learning style, print them out, cut them out, fold and glue them as cards and carry them everywhere with you. Use down time (waiting for a ride, at a doctors office, etc.) to review them. 3. Several songs exist for leaning the Hebrew alphabet in sequence. Most if not all of them can be found on YouTube, and you are welcome to use any one that you like. I personally like one song and included it in a document posted in the document library of our website. It is catchy and lively and easy to learn, and once you know it, you can always hum it to yourself if you forget the name of a particular letter. Writing Hebrew Letters 4. Many Bible scholars know a lot about the Bible, but when they write a word on the board what a disaster! If you are super ambitious, you may want to learn the cursive script, which is used in Modern Hebrew, and is easier to use (in such case, contact me). Otherwise, stick with the chart of the block letters with stroke directions. Every week, use it to do the writing homework, and if there is no writing in the homework, take a verse and practice. 5. When you writ Hebrew block letters, imagine an invisible rectangle within which the letter is written. Some letters fill the whole rectangle, some fill it vertically but are very narrow, one is so small that it does not fill it either way, and others stick out below or above the rectangle. Using the recommended stroke order will increase the chances of your doing so correctly. Hebrew Sounds 6. The Hebrew sound system is very simple. It has only five sounds (sounds are the audible outcome of vowels): ah, eh, ee, oh and oo. It is important not to equate Hebrew sounds with English letters, which sounds differently in different situation, e.g. the letter a in cat, father caught came and wall. 7. Because there are only five sounds, all you need to do to learn how to use them with letters is take a consonant and pronounce it with one of the five sounds: Aleph + ah = ah; Bet + ah = bah, etc. This is the traditional way children have been taught for century, only instead of ah, eh etc. they called out the vowels name.

Eichenberg-Eilon Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and Vocabulary (2012)

p. 1 of 4

Vowel Signs 8. Hebrew, like other Semitic languages, is a consonantal language. This means that the Hebrew alphabet, from A to Z sorry from Aleph to Tav, contains only consonants. The vowels were initially added from memory, and gradually developed into a separate system of vowel signs, consisting of groups of dots and lines placed under, inside or above the letters. 9. Learners of Modern Hebrew can get away without vowel signs. In fact, they hardly know them at all. But on the other hand, they need the skill of reading texts without vowel signs and knowing which sounds to use in them. 10. Biblical Hebrew learners need to know the vowel signs and their names because they are used later on in analyzing texts, identifying parts of speech, explaining changes in vowels, and differentiating between identical words with different vowels. 11. Hebrew has more vowel signs than its five sounds. This means that for each sound there are several vowel signs. The good news is (a) in Biblical Hebrew we read, but dont write, so we dont need to know which vowel sign to use they are already there; and (b) there are tricks to remind us to which sound a particular vowel sign belongs (and a song we can use as a mnemonic tool for that purpose). 12. I was unable to find any songs for learning the vowel signs, so I have created my own. It is not perfect (some of the meter is a little stiff) but it is based on a well known tune (London bridge is falling down, falling down, falling down) and separated into stanzas, each of which is focused on a sign or a group of signs, so you dont need to hum the whole song but go straight to the one you need. The song is likewise posted in the document library. 13. For those of you who want a more serious (and maybe tedious) way of learning letter+vowel combinations, I will post two color-coded documents. The color coding corresponds to the sound of the vowel. For example green represents the sound ee, blue the sound oo, etc. 1. A list of all the consonant + vowel sign combinations, so you can go, like in the traditional method: Aleph Kamatz Ah, Bet Kamatz Beh, Gimmel Kammatz Geh, etc. 2. An Excel chart of all the possible combination of consonant + vowel sign and vowel sign + consonant, which create open and closed syllables (you will soon find out the difference) that can result from such combinations. After using one of the methods above, I expect none of you to refer to the letter a in the name Yaacov (Jacob) as a (pron. ay) but as the sound ah or vowel sign x Hebrew Transliteration 14. There are many transliteration methods for Hebrew, each with its own purpose: the easiest to recognize, the most suitable for speaking, etc. 15. The method used in our course represents the way Hebrew words are written, not the way they sound. Therefore, even though several vowel signs produce the same sound, in the transliterated text they are represented by different signs. For example, the sound ah can be transliterated as a, , or , depending on the Hebrew vowel sign each of them represents. The reason for this is that, until you have enough practice and confidence to refer directly to the Hebrew signs, you have another tool, which reflects changes in vowels, which are important for explaining other phenomena.

Eichenberg-Eilon Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and Vocabulary (2012)

p. 2 of 4

Hebrew Syllables and Words 16. Words are made of Syllables. Syllables are combinations of consonants and vowels. 17. Hebrew syllables: a. Must begin with a consonant. When you think a syllable begins with a vowel, you must have forgotten that aleph and ayin, represented in the transliteration by or , are the invisible consonants preceding that vowel: Adam is in fact dm. b. May end with either a consonant (e.g. lot) or a vowel (e.g. go); c. A syllable may not contain two consecutive consonants (e.g. bread) d. A syllable can be open (CV, e.g. go) or closed (CVC, e.g. lot) 18. The shortest Hebrew words have one syllable, open or closed. In the first lesson you have learned eight of the 22 letters of the Hebrew language, and 15 vocabulary items made by combining those consonants with vowels, provided both as vowel signs (pending later explanation) and their transliteration. Those are summarized on page 2 of the book. 19. As a first exercise in syllabification (division of words into syllables), divide the onesyllable words into two groups: (a) open (CV); (b) closed (CVC). The two-syllable words are more difficult, because you have not yet learned the rules of syllabification, so I am using them as an example: a. = mar | mar = CV|CVC; = rh r | h = CV|CVC b. , however, uses the vowel sign , which complicates things, so well let it be for now. B. Learning Vocabulary 20. About memorizing vocabulary. Language learners often have the misconception that the way to learn new vocabulary is to memorize lists of words. The most effective way to learn vocabulary is in context. Once the terms have been learned, there is an important role for vocabulary lists, charts and flash cards as tools for review and repetition of vocabulary or for self-testing or mutual texting (working in pairs or groups) and creating artificial context. 21. Learning vocabulary in context. There are two types of context: a. Natural Contexts: In modern languages, natural context can be given immediately by the instructor, who often speaks only Hebrew to the students. It results from the very first conversations in class: Who are you? I am John Smith. In Biblical Hebrew, the natural context is the text of the Hebrew Bible. Period. Initially you will receive vocabulary out of any context. So what can you do? b. Artificial Context: Develop the habit from the very beginning to use new and learned vocabulary to create meaningful contexts. At first it will be awkward: in the first lesson there are 15 vocabulary items; what meaningful context can you create from 15 vocabulary items? Lets give it a try: Nouns (incl. proper nouns): brother; mother; mountain/hill; bread/food; stream/river, young man/lad; lamp; people

Eichenberg-Eilon Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and Vocabulary (2012)

p. 3 of 4

Prepositions & Particles: to/towards; from; upon; no/not Verbs: [he] said; [he] saw (verbs are initially presented in the 1p.m.s.) All but one noun are m.s. and can be used with the nouns as subjects. So we begin. We dont know yet how to use the definite article, so we put it in brackets:

[the] brother said = h mar = [ ; the] brother saw =h rh = [the] brother did not say = h l mar = [ ; the] brother did not see =h l rh = [the] brother saw [a] hill =h rh har = [ ; the] brother did not see a river =h l rh nhr =

Now we add the negative particle. Intuitively, we place it before the verb:

Next we add a direct object. Let us use the verb saw:

When all the reasonable combinations have been exhausted and we still have unused words, we can add the missing words in English, for example: [the] people went to Aram = am went el rm = 22. Every week you will receive a new list of 15 vocabulary units. The vocabulary previously learned will be used as much as possible, but it is never enough. Some terms may appear only occasionally, not enough to provide the repetition necessary for deep learning. This is where the habit of creating artificial context comes in handy: it forces you to pull out the old words and plug them into new constructions to be used with fresh vocabulary. Examples a. When we reach the unit with the definite article, you will go back to the vocabulary learned up to that point, pull out all the nouns and adjectives and combine them with and without the definite article. b. As you learn the use of prepositions for indirect objects, you will pull out all the verbs and reasonable objects for them and plug in all the new prepositions to see how they fit. 23. Natural Contexts, again: Soon you will begin to read actual biblical passages first very short and simple, and more complex as you progress. This provides you with a growing body of natural context for reviewing mostly new grammatical concepts, but also for vocabulary. a. Again, when we reach the definite article, you can go back to all the leaned passages and identify it, looking for the specific phenomena taught in that unit; b. You can also look for words that were previously used in passages (which will include invariably unlearned materials), searching for new vocabulary in context. 24. We will discuss all this in class and, when there is an opportunity to use these techniques, you will be advised.

Eichenberg-Eilon Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and Vocabulary (2012)

p. 4 of 4

You might also like

- Basic HebrewDocument6 pagesBasic HebrewNatalieRivkahAlexander0% (1)

- 1.4 Hebrew Guttural LettersDocument2 pages1.4 Hebrew Guttural LettersScott SmithNo ratings yet

- Hiphil Stem HebrewDocument3 pagesHiphil Stem HebrewAnthony PowellNo ratings yet

- 1.5 The Begedkephat LettersDocument3 pages1.5 The Begedkephat LettersScott Smith100% (1)

- Sheva and Dagesh ReviewDocument75 pagesSheva and Dagesh ReviewGudisa AdisuNo ratings yet

- The Hebrew Noun Presented in English and HebrewDocument44 pagesThe Hebrew Noun Presented in English and HebrewjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- The Hebrew Noun Presented in English and HebrewDocument44 pagesThe Hebrew Noun Presented in English and HebrewjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Biblical Hebrew Grammar Presentation PDFDocument245 pagesBiblical Hebrew Grammar Presentation PDFNana Kopriva100% (3)

- Hebrew Consonants VowelsDocument1 pageHebrew Consonants VowelsChi WanNo ratings yet

- 1 Kings 1-11: Adonijah Attempts to Seize the ThroneDocument95 pages1 Kings 1-11: Adonijah Attempts to Seize the ThronedaghaalsuiiNo ratings yet

- Spirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdDocument330 pagesSpirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdfcocajaNo ratings yet

- Alefbet Book PG 1 12Document11 pagesAlefbet Book PG 1 12Alexutu AlexNo ratings yet

- Samaritan HebrewDocument6 pagesSamaritan Hebrewdzimmer6No ratings yet

- Passive in HebrewDocument11 pagesPassive in Hebrewovidiudas100% (1)

- Grammatical Remarks: 1. The Hebrew Aleph-BethDocument6 pagesGrammatical Remarks: 1. The Hebrew Aleph-BethprogramandosumusicaNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Podcasts: Lesson 2 - AlphabetDocument9 pagesHebrew Podcasts: Lesson 2 - AlphabetSean C. TaylorNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Weak Verb Cheat SheetDocument1 pageHebrew Weak Verb Cheat SheetBenjamin GordonNo ratings yet

- The 53 Questions: Did Pre-Flood Humans Mate with AnimalsDocument54 pagesThe 53 Questions: Did Pre-Flood Humans Mate with AnimalsBlaceNo ratings yet

- Psalm 119 - Beit - CompletedDocument12 pagesPsalm 119 - Beit - CompletedChozehChristPhronesis100% (1)

- Tregelles. Hebrew Reading Lessons: Consisting of The First Four Chapters of The Book of Genesis, and The Eighth Chapter of The Proverbs. 1860?Document106 pagesTregelles. Hebrew Reading Lessons: Consisting of The First Four Chapters of The Book of Genesis, and The Eighth Chapter of The Proverbs. 1860?Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (3)

- Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyDocument4 pagesLearning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Hebrew ResourcesDocument5 pagesHebrew ResourcesjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Proofs Biblical Hebrew Periodization enDocument11 pagesProofs Biblical Hebrew Periodization enChirițescu Andrei100% (1)

- Fundamental Hebrew GrammarDocument40 pagesFundamental Hebrew Grammarjoabeilon100% (3)

- BIBS1300 02C Reading HebrewDocument35 pagesBIBS1300 02C Reading HebrewDavidNo ratings yet

- Use-Of OT-in NTDocument33 pagesUse-Of OT-in NTsorin71100% (1)

- Hebrew To LatinDocument10 pagesHebrew To LatinMitchell PowellNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Memorization Chapter 3Document2 pagesVocabulary Memorization Chapter 3Joshua DavidNo ratings yet

- Ancient Hebrew MorphologyDocument22 pagesAncient Hebrew Morphologykamaur82100% (1)

- Jesus Christ and His Revelation Revised and Updated: Commentary and Bible Study on the Book of RevelationFrom EverandJesus Christ and His Revelation Revised and Updated: Commentary and Bible Study on the Book of RevelationNo ratings yet

- Pocket Lexicon of Hebrew Words Occuring 2-49xDocument40 pagesPocket Lexicon of Hebrew Words Occuring 2-49xSimon PattersonNo ratings yet

- A Is for Abandon: An English to Biblical Hebrew Alphabet BookFrom EverandA Is for Abandon: An English to Biblical Hebrew Alphabet BookNo ratings yet

- Learn Basic HebrewDocument36 pagesLearn Basic HebrewEric Zong IINo ratings yet

- A Student's Introduction To Biblical Hebrew: What Are The Essential Features That You Need To Memorize in Chapter 1?Document9 pagesA Student's Introduction To Biblical Hebrew: What Are The Essential Features That You Need To Memorize in Chapter 1?ajakukNo ratings yet

- Masoretic PunctuationDocument26 pagesMasoretic PunctuationBNo ratings yet

- The Ancient Near East: Cradle of The JewsDocument37 pagesThe Ancient Near East: Cradle of The JewsjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Grammar Davidson PDFDocument264 pagesHebrew Grammar Davidson PDFvictor100% (1)

- Holman Bible AtlasDocument69 pagesHolman Bible AtlasBea Christian0% (1)

- Keter Torah DevarimDocument18 pagesKeter Torah DevarimSebastian HernandezNo ratings yet

- Divine Will and Human Experience: Explorations of the Halakhic System and its ValuesFrom EverandDivine Will and Human Experience: Explorations of the Halakhic System and its ValuesNo ratings yet

- Did Jesus Speak Hebrew? Evidence That Jesus Spoke the Language of His PeopleDocument4 pagesDid Jesus Speak Hebrew? Evidence That Jesus Spoke the Language of His PeopleScott SmithNo ratings yet

- Hebrew ShortStories Sample PDFDocument24 pagesHebrew ShortStories Sample PDFBurtNo ratings yet

- The Enigma of the Masoretic TextDocument26 pagesThe Enigma of the Masoretic TextAnonymous mNo2N3100% (1)

- Hebrew, #5475, Means Counsel, Confidentiality That Comes Only by Intimacy!Document9 pagesHebrew, #5475, Means Counsel, Confidentiality That Comes Only by Intimacy!David MathewsNo ratings yet

- Baruch She 'Amar Teaching Guide: by Torah Umesorah Chaim and Chaya Baila Wolf Brooklyn Teacher CenterDocument10 pagesBaruch She 'Amar Teaching Guide: by Torah Umesorah Chaim and Chaya Baila Wolf Brooklyn Teacher CenterMárcio de Carvalho100% (1)

- Introductory Biblical HebrewDocument98 pagesIntroductory Biblical Hebrewjoabeilon100% (1)

- HebrewDocument7 pagesHebrewsalvoreyNo ratings yet

- Transliterating English Into HebrewDocument2 pagesTransliterating English Into HebrewOmbre d'OrNo ratings yet

- Joshua in E-Prime With Interlinear Hebrew in IPA (9!7!2016)Document169 pagesJoshua in E-Prime With Interlinear Hebrew in IPA (9!7!2016)David F MaasNo ratings yet

- Joshua in E-Prime With Interlinear Hebrew in IPA (9!7!2016)Document169 pagesJoshua in E-Prime With Interlinear Hebrew in IPA (9!7!2016)David F MaasNo ratings yet

- Hebrew OtDocument1,098 pagesHebrew OtKomishinNo ratings yet

- LDS Old Testament Handout 26: DanielDocument2 pagesLDS Old Testament Handout 26: DanielMike ParkerNo ratings yet

- Biblical Hebrew (SIL) ManualDocument13 pagesBiblical Hebrew (SIL) ManualcamaziNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Memorization Chapter 8Document2 pagesVocabulary Memorization Chapter 8Joshua DavidNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Aleph-Bet and Letter As Numbers: Letter Name in Hebrew Keyboard Letter Number ValueDocument2 pagesHebrew Aleph-Bet and Letter As Numbers: Letter Name in Hebrew Keyboard Letter Number ValueTonio RheygieNo ratings yet

- Hebrew JournalDocument168 pagesHebrew JournalbinifsNo ratings yet

- HebrewDocument3 pagesHebrewJust In the RealNo ratings yet

- Hebrew PDFDocument51 pagesHebrew PDFMath Mathematicus0% (1)

- Niccacci-BH Verbal SystemDocument21 pagesNiccacci-BH Verbal Systemclaudia_graziano_3100% (2)

- Biblical Abbreviations and TermsDocument1,750 pagesBiblical Abbreviations and TermsBrian Berge100% (2)

- An Easy Practical Hebrew Grammar MasonVol1 PDFDocument625 pagesAn Easy Practical Hebrew Grammar MasonVol1 PDFafflanteNo ratings yet

- Ancient Hebrew PhonologyDocument20 pagesAncient Hebrew PhonologyjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Thanksgiving in Jewish LiturgyDocument3 pagesThanksgiving in Jewish LiturgyjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Uploaded by MistakeDocument1 pageUploaded by MistakejoabeilonNo ratings yet

- From Cuneiform To ABGD - Visual PresentationDocument1 pageFrom Cuneiform To ABGD - Visual PresentationjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- The Hebrew Bible in S NutshellDocument4 pagesThe Hebrew Bible in S NutshelljoabeilonNo ratings yet

- From Bible To Rabbinic Literature in A NutshellDocument3 pagesFrom Bible To Rabbinic Literature in A NutshelljoabeilonNo ratings yet

- 1) Remained in Ur 2) Left Ur For Haran 2) Left Haran For CanaanDocument1 page1) Remained in Ur 2) Left Ur For Haran 2) Left Haran For CanaanjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Torah Hebrew PDFDocument323 pagesTorah Hebrew PDFjoabeilon50% (2)

- Hebrew Letters Vowel Practice Grid Modern Color CodedDocument1 pageHebrew Letters Vowel Practice Grid Modern Color CodedjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- The Mourners KaddishDocument1 pageThe Mourners KaddishjoabeilonNo ratings yet