Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rubin Harvard Speech

Uploaded by

RaviOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rubin Harvard Speech

Uploaded by

RaviCopyright:

Available Formats

Thank you very much, Scott.

Mr President, fellows of Harvard, Madame President, members of the board of overseers, distinguished faculty, todays graduates and their families, and alumni. I mentioned at lunch that Larry Summers had asked me last night what the second hour of my speech was going to be like, I suggested that he pay a lot of attention to it because it not only builds on the first hour but it foreshadowed what was to come. So well be with each other for a while. I am deeply honored to be your commencement speaker today. Little over 40 years ago, I arrived as a freshman of Harvard College from a public school in Miami beach Florida. I remember the first day of orientation, when the incoming freshmen class met together at the Memorial Hall and the acting Dean of Freshmen, as an effort of reassurance, said that only two percent of the incoming class would fail out. Well, it may seem funny today, it didnt seem so funny then, because I felt that I was providing enormous protection to the rest of my class since I figured I fall so far short as to fill the whole two percent all by myself. However I remained and my Harvard experience reshaped the intellectual framework through which I viewed everything that came my way, including the decision making that has been the critical core of my professional life, both in Wall Street and in government. My views on that critical function of decision making, derived from my lifes experience and so formatively and powerfully affected by my Harvard experience, will be the primary focus of my remarks today because I believe that decision making is the core of all of our livestodays graduates, the alumni, and all of us, no matter who we are or what we may be doing. The only question will be how well we make those decisions. Larry Summers, my former colleague at treasury and your outstanding incoming president used to say when we face top situations in Washington that life is about making choices and I think that is exactly right. Curiously though, despite this profoundly important reality, most people seem to give very little consideration to how they make those choices. Thus I would add to Larrys comment that how thoughtfully you make those choices will greatly affect the quality of those choices and how effective you will be. In addition to discussing decision making, Ill end my remarks today by urging that todays graduates and the alumni here today as well, consider spending at least some of your careers in public service where so many of our societies most complex decisions, affecting the lives of all of us, must be made. Sophomore year in Emerson Hall, I took Philosophy 1 with professor Rafael Dimos. I still remember the first day of class when a relatively short, white-haired, elderly Greek man walked on to the stage in Lecture Hall and instead of using a podium, turned a waste basket upside down on a desk, put his notes on top, and started to speak. That unadorned simplicity, in the best sense of the word,

permeated his thinking and his teaching. And Philosophy 1 was only part of a broader in Harvard intellectual experience that provided my most important training for subsequent careers on Wall Street and in economic policy making in government. Professor Dimos would lead us to the great philosophical thinkers of the ages, not in the spirit of simply understanding and accepting their views, but rather to use their views as launching pads for our own critical thinking. To question how well each thinkers points, stood up to critical analysis, and most importantly, to question how each assertion of truth was proven and as I slowly came to realize, the absolute trues that were asserted turned out to be unprovable, & in the final analysis to be based on belief or assumption. I also remember that after we have struggled with thinkers works that were immensely difficult, professor Dimos then assigned us another set of thinkers whose work was relatively easy to understand. However, we came to realize, and he later acknowledged that this was his purpose in those assignments, that this group lacked the trying but tight rigor and discipline of Kant or Spinoza. And seeing it intellectually loose and unsatisfying, we then returned to the more difficult philosophers with a renewed appreciation for tight analytic rigor. From the guidance of this gentle professor and from all my other experience at Harvard, I developed, in the core of my being, the view that there are no provable absolutes and with the absence of provable certainty that all decisions are about probabilitiesthat is, all decisions are about the respective odds of each of a number of possible outcomes actually taking place. Moreover, it seems to me that once you recognize that all decisions are about probabilities rather than certainties, that leads you to uncovering and engaging with the full range of complexities around making the best decisions. Perhaps most importantly, rejecting the idea of certainties, and needing to make the best possible judgments about probabilities, should drive you restlessly and rigorously to analyze and question whatever is before you and to treat assertions as the beginning points for analysis, not as accepted truths. Moreover, judging probabilities is far from the only complexity in decision making. Often, each alternative possible outcome is not a simple single effect but the net result of tradeoffs between competing effects. Im not expecting or intending in these remarks to fully explore these thoughts, but rather simply to convey my view as to the intellectual complexity inherent in making good decisions. To exemplify both probabilities and tradeoffs, when a new administrations economic team opted for deficit reduction to stimulate the economic recovery in 1993, we told President Clinton that we believed that likelihood that this program would worked was very good but that there were no guarantees so that he could make the decision on a dramatic change in fiscal policy with full awareness of the

economic and political risks. We also said that even if the strategy did work, the result would be a tradeoff, as I said a moment ago, between competing effectsthe positive effect of economic recovery and the negative effect of having to forego spending on programs that he cared so deeply about. Again, as Larry said, life is about making choices and that quickly leads you to probabilities and tradeoffs. With that, let me make one final point about how complex decision making can sometimes be; the point that sometimes all choices are bad but some are better than others. For example, our administration was greatly criticized for having worked with the international monetary fund to extend support for Russia in 1998 when Russia was facing a severe economic and financial crisis. Clearly, there was substantial risk that additional assistance would not work and would not be effective. On the other hand, there was no question that our country had a very substantial national security interest in attempting to help stave off crisis in Russia. All choices were probably bad in that case, including doing nothing, but there was still one choice that was least bad. Often, decision makers faced with a situation where all choices are bad react by not deciding. That however, is a decision in itself and often the wrong decision. Let me briefly mention one of the situations that exemplifies what Ive been saying about decision making. I often remember an experience early in my own Wall Street career, when I was investing our firms capital in an activity known as risk arbitrage, and a friendly competitor, in another firm, explained his massive investment in what he viewed as a sure thing. I agreed that it looks certain, but in the theory that there are no certainties but only probabilities, Ive made a very large investment but still at a level with a loss that was absorbable by our firm - if the entirely unexpected happened. The entirely unexpected did happen. The investment failed. We took a large loss and he took a loss beyond reason and lost his job. I doubt if Kant or Spinoza viewed themselves as offering the best and most important advice or preparation for risk arbitrage or for intervention of the dollaryen relationship or the many other activities of finance minister, but in my view they did. Looking back on all my years in the private and public sector, in the most important issues, certainties were almost always illusionary and misleading, as were the simple answers or opinions, and so often were the response to complicated issues in both political discourse and the private sector. Reality is complex and recognizing complexity and engaging with complexity, was the path to the best decision making. Thus, as todays graduates leave Harvard to undertake a vast variety of pursuits and as your alumni, engage in the vast variety of pursuits in which you were involved, I believe that nothing is important nor experience or professional

training as the ways of thinking and the restless pursuit of understanding, we have all had the opportunity to develop at this great institution. An important corollary to recognizing that decisions are about probabilities, at least in my view, is that decision should be judged not by outcomes but by the quality of the decision-making, though outcomes are certainly one useful input in that evaluation. Any individual decision can be badly thought through, and yet successful, or exceedingly well thought through, but be unsuccessful, because the recognized possibility of failure actually occurs. But over time, more thoughtful decision making will lead to better results and more thoughtful decision making can be encouraged by evaluating decisions on how well they are made rather than on the outcome. In managing trading rooms for 26 years, I always focused on evaluating promoting traders not on their results alone, but also and very importantly, on the thinking that underlay their decisions. Unfortunately this approach is not widely taken much to the detriment of decision making in both the private and public sectors. In Washington for example, where I spent six and a half years, there is very little tolerance for decisions that dont turn out to be successful, creating a counterproductive tendency to risk aversion. In 1995 for example, our administration decided to assist Mexico, in attempting recovery from an economic crisis and program succeeded. Then 3 years later, we made a conceptually similar decision, which Ive already mentioned, with regard to Russia and the effort did not succeed. I believe that the decision on Mexico would have been right even if the program had failed and the decision on Russia was right even though it did failed. In both cases we knew there were no guarantees of success, and in fact real chances of failure, but we also felt that the chance of success were good enough and the consequences of not engaging were severe enough threat to American economic and national security interests that involvement was the right decision. We were praised for the Mexican decision and criticized for the Russian decision. In both cases because of the outcomes, but I think those reactions were based on looking at the wrong thing. And that has real consequences. In the Mexican case, President Clinton made the decision well knowing that failure could cause him enormous political damage and that the judgment and evaluation of the decision in the media and the political process would be based solely on the outcome. Fortunately, President Clinton was willing to take that risk, but too often in this environment, it deters optimal decisions where there is a risk of failure. And that leads me to the thoughts on public service I mentioned at the beginning of my remarks. When I began in the new administration, the distinguished former cabinet member and graduate of this university told me that I will now live off my previously accumulated intellectual capital because I would be too busy to add to it. I found just the opposite that my time in government was an intense learning experience

about how our government and political processes work and about a vast array of policy issues. I also found that decisions that had to be made were often amongst the most complex faced anywhere on our society. Public service was a powerful challenge and using all the intellectual qualities that Harvard had sought to develop toward the objective of furthering the public good. I believe strongly in a market-based private sector economy but there are host of critically important functions that markets, by their nature, cannot and will not perform optimally, from education programs within the cities, law enforcement environmental protection, to defense and foreign policy and this array of functions becomes greater in a world of increasing global interdependence. Thus, we must attract to government a critical mass of people with the intellectual drive, restless quest for understanding, and the effectiveness of decision making that weve been discussing this afternoon. There was a terrible period during my time in government when radio talk shows and even important elected officials derogated public service and public servants. The atmosphere around government has substantially improved in recent years but simply reducing the level of derogation is not enough. The people I worked within government were as capable and committed as any I have any worked with any place, but to continue to attract the outstanding people to public service that the issues and the functions require, will I believe imposed an obligation on all of us, especially those of us who have received the benefits of our great universities to reject the denigration of public service and to help re-establish an environment of honor and respect for public service and public servants. None of this, let me quickly add, has anything to do with the perfectly proper debate about the appropriate role of government in our society. That debate is as old as our republic and the role of government in our society has fluctuated substantially over time. However, what should not be a matter of debate, no matter what ones views maybe as to the role of government, is the respect that we accord public service and public servants. Beyond origin to all of us contribute to reestablishing that environment of respect, I would also urge those of you who are here today, alumni and graduating students, to consider spending at least some time and hopefully for some of your career to public service. Public service at whatever lever of seniority can provide immense challenge to all of your capabilities as you help make and execute decisions in the most complex of circumstances and decisions that will profoundly affect the lives of all of us, and you get a very special insight to many of our societys most important policy decisions and into how our society works. For example, how policy, politics, and the media interact to affect what happens.

Government servers, whether for a few years or for a career, can provide enormous challenge and intellectual growth and the satisfaction of working to directly further the public good. With that, let me conclude by thanking you with the opportunity to share views that I have thought a great deal about over the years. Important issues are complicated and many of the most complicated are involved in the immense challenges requiring effective governance in our country and throughout the world. You who are graduating today and you, who are alumni, have been prepared by an outstanding institution, Harvard, to deal with this complexity whatever you do and to contribute greatly to that governance. Thus, you have an extraordinary opportunity to develop lives that work for you and to serve your country and all human kind. That is a wonderful prospect. Let me also say to the graduates specifically that I congratulate each of you graduating today on all that you have accomplished and on this momentous day in your lives. I wish each graduate the best in the years and decades ahead and I hope all of you will cherish and advance in the world the great intellectual traditions that Harvard represents, as so many of your predecessors have, before you. Thank you very much.

You might also like

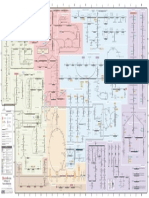

- A B C D E F G H I J K L M: Pathways of Human MetabolismDocument1 pageA B C D E F G H I J K L M: Pathways of Human MetabolismPranavJamdagneyaSharmaNo ratings yet

- Wait But Why History TimelineDocument1 pageWait But Why History TimelineRaviNo ratings yet

- An Evolutionary Theory of Dentistry (Science 2012 Gibbons)Document3 pagesAn Evolutionary Theory of Dentistry (Science 2012 Gibbons)RaviNo ratings yet

- Polanyi's Paradox and The Shape of Employment GrowthDocument47 pagesPolanyi's Paradox and The Shape of Employment GrowthribbedtrojanNo ratings yet

- Nassim Talib - Heuristics (Via Twitter)Document21 pagesNassim Talib - Heuristics (Via Twitter)RaviNo ratings yet

- Fat PDFDocument84 pagesFat PDFAravind MNo ratings yet

- Deconstruction BuddhismDocument430 pagesDeconstruction BuddhismIlkwaen Chung100% (4)

- Intensely Pleasurable Responses To Music Correlate With Activity in Brain Regions Implicated in Reward and EmotionDocument6 pagesIntensely Pleasurable Responses To Music Correlate With Activity in Brain Regions Implicated in Reward and EmotionRaviNo ratings yet

- The Rewards of Music Listening: Response and Physiological Connectivity of The Mesolimbic SystemDocument10 pagesThe Rewards of Music Listening: Response and Physiological Connectivity of The Mesolimbic SystemRaviNo ratings yet

- New Yorker MagazineDocument30 pagesNew Yorker MagazineRaviNo ratings yet

- Andy Clark - WhatevernextDocument73 pagesAndy Clark - WhatevernextIvanSmiljkovićNo ratings yet

- The Road to Lifelong Learning and GrowthDocument5 pagesThe Road to Lifelong Learning and GrowthKonstantin KakaesNo ratings yet

- San Francisco Mission Rock Community Design WorkshopDocument67 pagesSan Francisco Mission Rock Community Design WorkshopRaviNo ratings yet

- Richard HammingDocument37 pagesRichard Hammingnovrain100% (1)

- The Assessment of Creativity: An Investment Based ApproachDocument10 pagesThe Assessment of Creativity: An Investment Based ApproachRavi100% (1)

- Masters Thesis - Toward Service Oriented Architecture: An Insight Into Web ServicesDocument66 pagesMasters Thesis - Toward Service Oriented Architecture: An Insight Into Web ServicesRaviNo ratings yet

- Striking ThoughtsDocument83 pagesStriking ThoughtsRavi100% (2)

- James Montier - Darwin's Mind: The Evolutionary Foundations of Heuristics and BiasesDocument31 pagesJames Montier - Darwin's Mind: The Evolutionary Foundations of Heuristics and BiasesRaviNo ratings yet

- Masters Thesis - Toward Service Oriented Architecture: An Insight Into Web Services - Google Search ImplementationDocument18 pagesMasters Thesis - Toward Service Oriented Architecture: An Insight Into Web Services - Google Search ImplementationRaviNo ratings yet

- Dweck MindsetDocument1 pageDweck MindsetRaviNo ratings yet

- Emerging Trends in Real Estate 2013Document104 pagesEmerging Trends in Real Estate 2013RaviNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ADR R.A. 9285 CasesDocument9 pagesADR R.A. 9285 CasesAure ReidNo ratings yet

- Kursus Binaan Bangunan B-010: Struktur Yuran Latihan & Kemudahan AsramaDocument4 pagesKursus Binaan Bangunan B-010: Struktur Yuran Latihan & Kemudahan AsramaAzman SyafriNo ratings yet

- Advanced VocabularyDocument17 pagesAdvanced VocabularyHaslina ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: 0450/22 Business StudiesDocument12 pagesCambridge IGCSE: 0450/22 Business StudiesTshegofatso SaliNo ratings yet

- Guide Internal Control Over Financial Reporting 2019-05Document24 pagesGuide Internal Control Over Financial Reporting 2019-05hanafi prasentiantoNo ratings yet

- UP Law Reviewer 2013 - Constitutional Law 2 - Bill of RightsDocument41 pagesUP Law Reviewer 2013 - Constitutional Law 2 - Bill of RightsJC95% (56)

- What Is Leave Travel Allowance or LTADocument3 pagesWhat Is Leave Travel Allowance or LTAMukesh UpadhyeNo ratings yet

- To Sell or Scale Up: Canada's Patent Strategy in A Knowledge EconomyDocument22 pagesTo Sell or Scale Up: Canada's Patent Strategy in A Knowledge EconomyInstitute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP)No ratings yet

- G.O.MS - No. 578 Dt. 31-12-1999Document2 pagesG.O.MS - No. 578 Dt. 31-12-1999gangaraju88% (17)

- Sample Business Plans - UK Guildford Dry CleaningDocument36 pagesSample Business Plans - UK Guildford Dry CleaningPalo Alto Software100% (14)

- NOMAC Health and Safety AcknowledgementDocument3 pagesNOMAC Health and Safety AcknowledgementReynanNo ratings yet

- AHMEDABAD-380 014.: Office of The Ombudsman Name of The Ombudsmen Contact Details AhmedabadDocument8 pagesAHMEDABAD-380 014.: Office of The Ombudsman Name of The Ombudsmen Contact Details AhmedabadPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- Magnitude of Magnetic Field Inside Hydrogen Atom ModelDocument6 pagesMagnitude of Magnetic Field Inside Hydrogen Atom ModelChristopher ThaiNo ratings yet

- Carey Alcohol in The AtlanticDocument217 pagesCarey Alcohol in The AtlanticJosé Luis Cervantes CortésNo ratings yet

- Milton Ager - I'm Nobody's BabyDocument6 pagesMilton Ager - I'm Nobody's Babyperry202100% (1)

- Torts For Digest LISTDocument12 pagesTorts For Digest LISTJim ParedesNo ratings yet

- Switch Redemption Terms 112619Document2 pagesSwitch Redemption Terms 112619Premkumar ManoharanNo ratings yet

- Ortega V PeopleDocument1 pageOrtega V PeopleDan Alden ContrerasNo ratings yet

- 1.18 Research Ethics GlossaryDocument8 pages1.18 Research Ethics GlossaryF-z ImaneNo ratings yet

- United States v. Devin Melcher, 10th Cir. (2008)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Devin Melcher, 10th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

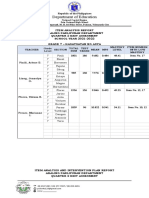

- Item Analysis Repost Sy2022Document4 pagesItem Analysis Repost Sy2022mjeduriaNo ratings yet

- Apple Strategic Audit AnalysisDocument14 pagesApple Strategic Audit AnalysisShaff Mubashir BhattiNo ratings yet

- ISLAWDocument18 pagesISLAWengg100% (6)

- NLIU 9th International Mediation Tournament RulesDocument9 pagesNLIU 9th International Mediation Tournament RulesVipul ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Democratization and StabilizationDocument2 pagesDemocratization and StabilizationAleah Jehan AbuatNo ratings yet

- PenaltiesDocument143 pagesPenaltiesRexenne MarieNo ratings yet

- Taxation Full CaseDocument163 pagesTaxation Full CaseJacquelyn AlegriaNo ratings yet

- Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocument9 pagesDate Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceN.prem kumarNo ratings yet

- Nabina Saha ThesisDocument283 pagesNabina Saha Thesissurendra reddyNo ratings yet

- Paper On Society1 Modernity PDFDocument13 pagesPaper On Society1 Modernity PDFferiha goharNo ratings yet