Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Uploaded by

Jamiu OlusholaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Uploaded by

Jamiu OlusholaCopyright:

Available Formats

LAGOS STATE UNIVERSITY (LASU) LEKKI EXTERNAL CAMPUS FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

BY OGBU BENEDICTA ADERELE MATRIC NO: 07098214807 COURSE CODE: FMS 500

COURSE TITLE: ENTREPRENEURSHIP

FEBRUARY 2013

1

INTRODUCTION The entrepreneurial process involving all the functions, activities, and actions associated with the perception of opportunities and creation of organizations to pursue them has generated considerable academic interest. However, there is a lack of an agreed definition of entrepreneurship and a concern over what

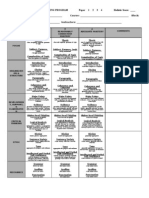

entrepreneurship constitutes as a field of study. Like many other disciplines, there is growing concern that entrepreneurship as a discipline is fragmented among specialists who make little use of each others work (e.g., researchers following the phenomenological paradigm rather than positivist paradigm). Fragmentation hinders the full advance of knowledge, because it creates parts without wholes, disciplines without cores. Most notably, there is concern whether the issue of wealth creation is being adequately explored. The diversity of wealth creation is manifold. Our mission within academia is to describe and account for that diversity. To achieve this mission, we must promote the study of entrepreneurship and we must not constrain our definition of the context for entrepreneurship. This raises the question of the focus of research in the field of entrepreneurship. To encourage the advancement and propagation of knowledge in the field of entrepreneurship, this paper develops the focus theme and issues associated with entrepreneurship are highlighted to integrate research focusing upon the entrepreneurial phenomenon. The aim of this paper is to encourage additional research rather than providing an exhaustive review of all themes worthy of debate in the field of entrepreneurship. Gartner (1985) presented a conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation that integrated four major perspectives in entrepreneurship: the characteristics of the individual(s) starting the new venture; the organization they create; the environment surrounding the new venture; and the process by which the new venture is created. This paper takes the approach that the processes associated with the entrepreneurial phenomenon can be discussed with regard to opportunity recognition and exploitation by entrepreneurs; ability based on skills, competencies and knowledge; and ability to obtain resources and co-ordinate scarce resources (Low and MacMillan, 1988; Shane and Venkataraman, 2000). The context of the entrepreneurial phenomenon for illustration can be discussed, not only in terms of the creation of new independent firms, but also in terms of corporate ventures (McGrath, Venkataraman and MacMillan, 1994), management buy-outs and buy-ins (Wright and Coyne, 1985), franchising (Shane, 1996) and the inheritance and development of family firms (Church, 1993). The objective of the paper is to identify a set of themes that best illustrate progress and developments in the focus of entrepreneurship research. Following a review of existing literature surrounding these themes, several research gaps that need to be addressed. Key aspects of the entrepreneurial process and context are highlighted in Figure 1. The exposition in the paper follows the themes highlighted in the figure. First, we examine the changing focus of the nature of entrepreneurship theory, and in particular the shift of emphasis towards the examination of behavior. Second, we review studies focusing upon different types of entrepreneur. Third, the process of

entrepreneurship is examined in terms of: (a) studies focusing upon opportunity recognition, information search and learning, and (b) resource acquisition and competitive strategies selected by entrepreneurs. Fourth, organizational modes selected by entrepreneurs are examined with regard to corporate venturing, management buy-outs and buyins, franchising and the inheritance of family firms. Fifth, the external environment for entrepreneurship is

discussed. Sixth, the outcomes of entrepreneurial endeavors are analyzed. Finally, some conclusions are drawn and themes worthy of additional research attention are identified based on the dimensions identified in Figure 1. THEME 1: ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY Within the study of entrepreneurship, a variety of approaches have been selected to describe entrepreneurs.

The cognitive processes in the decision making reported by entrepreneurs have also been explored (Manimala, 1992; Palich and Bagby, 1995, Baron, 1998). A particularly promising research focus has been entrepreneurial cognition, the way entrepreneurs think and the individual decision-making processes or heuristics adopted by entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs regularly find themselves in situations that tend to maximize the potential impact of various heuristics (Baron, 1998). Busenitz and Barney (1997) have argued that the level of uncertainty entrepreneurs face is substantially greater than that of managers of well-established organizations who have access to historical trends, past performance, and other information that can usually be readily obtained. Entrepreneurs often have to make decisions with little or no historical trends, no previous levels of performance, and little if any specific market information surrounding whether new products or services will be accepted. However,

entrepreneurs can gain new insights from interpreting new combinations of information via unique heuristic-based logic. Simplifying heuristics may have a great deal of utility in enabling entrepreneurs to make decisions that exploit brief windows of opportunity (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974; Stevenson and Gumpert, 1985). We develop below the implications of this approach for the understanding of entrepreneurial behavior by different types of entrepreneur and within different organizational forms. THEME 2: TYPES OF ENTREPRENEURS Studies have made a distinction between nascent (i.e., individuals considering the establishment of a new business), novice (i.e., individuals with no prior business ownership experience as a business founder, an inheritor or a purchaser of a business), habitual (i.e., individuals with prior business ownership experience), serial (i.e., individuals who have sold / closed their original business but at a later date have inherited, established and / or purchased another business), and portfolio entrepreneurs (i.e., individuals who have retained their original business but a later date have inherited, established and / or purchased another business). There is an increased awareness of the need for a greater understanding of the processes and strategies selected by different types of entrepreneurs to grow their ventures. Studies have begun to focus upon the pre-venture creation stage during which individuals may be described as nascent entrepreneurs (Delmar and Davidsson, 2000). Reynolds (1997) found that nascent entrepreneurs are not homogeneous, with the age of the entrepreneur and their previous employment status being important discriminators. Carter, Gartner and Reynolds (1996) showed that the individuals actually found to establish a business had undertaken more activities, including gathering the necessary resources, to ensure that their business idea was tangible than those who had given up. Longitudinal studies are important in order to provide insights into the extent to which nascent entrepreneurs actually start businesses and the processes that are involved. Additional research in this area might usefully examine the links between pre-start-up activities and venture success rates. Studies seem to be warranted that focus upon whether the difference between those individuals who successfully start a business and those who give up is attributable to the nature of the opportunity, to the commitment and expectations of the nascent entrepreneur or to the level of resource availability in the external environment. Alsos and Kolvereid (1998) have presented a study that begins to shed light on these issues. They found that portfolio founders had a higher probability of venture implementation than novice or serial founders. Attempts have been made to identify the relevant characteristics of entrepreneurs that may be linked to new venture success. Several studies have suggested that entrepreneurs, whether involved in start-ups or buy-outs and buy-ins can be divided into two broad types, namely, craftsmen or opportunists with differing growth potential.

Woo, Cooper and Dunkelberg (1991) have challenged the usefulness of this dichotomy. They suggest that there may be other types of entrepreneur that still have not been identified. One dimension of the heterogeneity of entrepreneurial types, that has until recently been neglected, is the possibility that entrepreneurs may be involved in more than one venture. Dyers (1994) work on entrepreneurial careers, for example, is couched very much in terms of an individuals development within a growing busi ness over time. In contrast, an entrepreneurs decision to exit from an initial venture raises important issues about the factors that influence the subsequent decision to exit completely from an entrepreneurial career or to own a further venture. Ronstadt (1986) has provided an exploratory examination of why, when and how entrepreneurs end their entrepreneurial careers. It is widely believed that an entrepreneur only starts another business when the first one fails (Dyer, 1994) but exit from a venture may depend on an entrepreneurs own threshold of performance (Gimeno, Folta, Cooper and Woo, 1997). Using a real options perspective, McGrath (1999) has argued that entrepreneurs may learn from the experience of owning a business that ceased to trade (or failed) to avoid repeating mistakes in subsequent ventures. Westhead and Wright (1998a, 1998b, 1999) have identified differing characteristics and motivations of novice, serial and portfolio founders. Interestingly, they found no significant differences between the performance of the surveyed firms owned by habitual and novice founders but that a skewed pattern of absolute employment growth was more prevalent in businesses owned by habitual entrepreneurs (particularly, those located in rural environments) than by novice founders. A crucial, though relatively neglected, dimension of research on types of entrepreneur has been in the area of entrepreneurial teams. Kamm and Shuman (1990) reviewed several studies and noted that 50% of businesses were started by entrepreneurial teams. Businesses owned by teams have generally more diversified skills and competence bases to draw upon alongside a wider social and business network, which can be used to acquire additional resources. Teams can also increase the legitimacy of the business, particularly when trying to secure financial resources (Fiet, Busenitz, Moesel and Barney, 1997). It is important to acknowledge that entrepreneurial teams are not exclusive to start-ups. Wright and Coyne (1985) and Baruch and Gebbie (1998), for example, have explored entrepreneurial teams in the context of management buy-outs. However, there has been limited research exploring the dynamics of entrepreneurial teams (Ensley, Carland, Carland and Banks, 1999) such as the process of effectively assembling and maintaining entrepreneurial teams (see Birley and Stockley, 2000 for a review of existing literature). It is clear from the above discussion that entrepreneurs are not a homogeneous entity. Moreover,

entrepreneurship is not necessarily a single-action event. Entrepreneurs, among themselves, may display differing characteristics and patterns of behavior that warrants research into different types of entrepreneurs. Alongside the entrepreneur, the entrepreneurial process is also a crucial dimension of entrepreneurship research. This dimension is highlighted in the following section. THEME 3: THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PROCESS This section examines two broad dimensions of the entrepreneurial process: opportunity recognition and information search, and resource acquisition and business strategies. Opportunity Recognition and Information Search While opportunity recognition (Kirzner, 1973) and information search are often considered to be the first critical steps in the entrepreneurial process (Christensen, Madsen and Peterson, 1994; Shane and Venkataraman, 2000),

limited empirical research has been conducted surrounding this process. Venkataraman (1997) argues that one of the most neglected questions in entrepreneurship research is whe re opportunities come from. Why, when and how certain individuals exploit opportunities appears to be a function of the joint characteristics of the opportunity and the nature of the individual (Shane and Venkataraman, 2000). Venkataraman (1997) highlighted three main areas of difference between individuals that may help us understand why certain individuals recognize opportunities while others do not: knowledge (and information) differences; cognitive differences; and behavioral differences. The ability to make the connection between specific knowledge and a commercial opportunity requires a set of skills, aptitudes, insights, and circumstances that are neither uniformly nor widely distributed (Venkataraman, 1997). The extent to which individuals recognize opportunities and search for relevant information can depend on the make-up of the various dimensions / aspects of an individuals human capital. Kirzner (1973) asserted that the entrepreneur identifies opportunities by being 'alert' to and 'noticing' opportunities that the market presents. The process of search and opportunity recognition can be influenced by the cognitive behaviors of entrepreneurs. Search behavior can be bounded by the decision-makers knowledge of how to process informatio n as well as the ability to gather an appropriate amount of information (Woo, Folta, and Cooper, 1992). Entrepreneurs with limited

experience may use simplified decision models to guide their search, while the opposite may be the case with experienced entrepreneurs (Gaglio, 1997). Experience may not strictly enhance opportunity recognition ability. Habitual entrepreneurs associated with liabilities (e.g., over-confidence, subject to blind spots, illusion of control, etc.), resulting from their prior business ownership experience, may also exhibit limited and narrow information search. Cooper, Folta and Woo (1995) found, however, that novice entrepreneurs sought more information than entrepreneurs with more entrepreneurial experience, but they searched less in unfamiliar surroundings. Further, entrepreneurs having high levels of confidence sought less information. Some experienced entrepreneurs may simply have had a fortuitous prior business ownership experience and may subsequently have little idea about identifying additional profitable projects. Over time, however, habitual entrepreneurs are likely to acquire information and contacts that provides them with a flow of information relating to opportunities. Consequently, habitual entrepreneurs may need to be less proactive compared with novice

entrepreneurs. Having earned a reputation as a successful entrepreneur, financiers, advisers, other entrepreneurs and business contacts may send proposals to previously successful habitual entrepreneurs. The ability of entrepreneurs to learn from previous business ownership experiences can influence the quantity and quality of information subsequently collected. Previous entrepreneurial experience may provide a framework or mental schema for processing information. In addition, it allows informed and experienced

entrepreneurs to identify and take advantage of dis-equilibrium profit opportunities. This entrepreneurial learning goes beyond acquiring new information by connecting and making inferences from various pieces of information that have not previously been connected. These inferences build from individual history and experience and often represent out-of-the-box thinking. Heuristics may be crucial to making these new links and interpretations. Some people habitually activate their mental schema for processing information and can notice it in the midst of an otherwise overwhelming amount of stimuli (Gaglio, 1997). This may explain why the pursuit of one set of ideas and opportunities invariably leads entrepreneurs to additional innovative opportunities that had not been previously recognized (Ronstadt, 1988). McGrath (1999) has argued that entrepreneurs have access to numerous shadow options (i.e., opportunities that have not been recognized). Over time, valuable information regarding the

real option can be made available or suitable venture opportunities emerge. Although McGrath focused on the ability to learn from entrepreneurial failure, shadow options may also arise with more successful entrepreneurs. There is limited evidence surrounding the search behavior of habitual entrepreneurs. Most notably, it is not clear whether ideas, projects and deals go to habitual entrepreneurs or whether habitual entrepreneurs initiate them. Case studies of habitual entrepreneurs have revealed that habitual start-up entrepreneurs were likely to be more proactive than habitual buy-out / buy-in entrepreneurs with regard to the search processes they adopted in subsequent ventures (Wright, Robbie and Ennew, 1997; Ucbasaran, Wright, Robbie and Westhead, 1999). Low and MacMillan (1988) suggested that networks are an important aspect of the context and process of entrepreneurship. Subsequent studies have found that networking allows entrepreneurs to enlarge their knowledge of opportunities, to gain access to critical resources and to deal with business obstacles. Businesses owned by teams of partners generally have wider social and business networks and more diversified skill and competence bases to draw upon. Once the opportunity has been identified and information relevant to the venture has been obtained, the next step for the entrepreneur (or the team of entrepreneurs) is to acquire new resources or effectively manage existing resources, in order to exploit the opportunity. entrepreneurial process are discussed in the following section. Research developments in these aspects of the

Resource Acquisition and Business Strategies Recent studies have attempted to examine entrepreneurs with respect to their resource endowments and resource acquisition strategies. The owner(s) of a business is likely to be its key resource (Storey, 1994; Westhead, 1995; Bates, 1998). Further, the owner(s) may be the key constraint on resource acquisition (Brown and Kirchhoff, 1997). Resources and assets (both tangible and intangible) are accumulated throughout entrepreneurial careers (Katz, 1994; Teece, Pisano and Shuen, 1997), for example, human, social, physical, financial and organizational capital (Cooper, Gimeno-Gascon and Woo, 1994; Greene and Brown, 1997; Hart, Greene and Brush, 1997). Although resources are crucial to the performance of a venture, resources alone are not sufficient to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. It follows that entrepreneurs must develop skills and select competitive strategies to make better use of the resources that are accessible to them. Based on the resource-based theory of the firm, Chandler and Hanks (1994) suggested that businesses should select their strategies to generate rents based upon resource capabilities. They argue that when there is a fit between the available resources and the ventures competitive strategies, firm performance should be enhanced. Additional firm-level studies are required to explore the relationship between entrepreneurial resources (and their acquisition and management) and the competitive strategies pursued by organizations (Zahra, Jennings and Kuratko, 1999).

THEME 4: ORGANIZATIONAL FORMS SELECTED BY ENTREPRENEURS As noted earlier, the organizational form an entrepreneurial venture takes is a crucial element of entrepreneurship research. However, as will be highlighted in the following discussion, there is considerable heterogeneity among organizational modes selected by entrepreneurs. In this section, four organizational forms the entrepreneurial venture may take are discussed: corporate venturing; the purchase of an existing organization through a management

buy-out or buy-in; the purchase of an existing organization through a franchise; and the inheritance and development of family firms. Corporate Venturing / Entrepreneurship A hierarchy of terminology to describe the corporate entrepreneurship phenomenon has recently been presented by Sharma and Chrisman (1999). Corporate entrepreneurship is a process of organizational renewal and is associated with two distinct but related dimensions (Guth and Ginsberg, 1990; Zahra, 1993; Zahra, Kuratko and Jennings, 1999). The first dimension stresses creating new businesses through market developments or by undertaking products, process, technological and administrative innovations. The second dimension is associated with the redefinition of the business concept, reorganization, and the introduction of system-wide changes for innovation. It is possible to identify the antecedents to the development of corporate venturing that are necessary to successfully combat bureaucratic processes and procedures that are linked to organizational inflexibility in large corporations. Several studies (Zahra, 1993; Covin and Miles, 1999; Russell, 1999) have also shown that the characteristics of the environment play an important role in executives pursuits of corporate entrepreneurship and in the resultant performance. Zahra and Covin (1995) argue that although there has been considerable theoretical discussion about the potential benefits of corporate venturing, and extensive anecdotal evidence regarding its impact, there has been little systematic analysis (also see Dess, Lumpkin and McGee (1999)). Their longitudinal study concluded that corporate venturing was particularly effective for enterprises operating in hostile environments and that its effects may only fully emerge in the long-term. Different conceptualizations of firm-level entrepreneurship need to be explored. For example, different conceptualizations of the link between entrepreneurial activities and company performance are warranted. Large sample studies conducted in a wide range of industrial, regional, national and cultural environments are required to explore the interplay between environment, corporate entrepreneurship and financial performance. Several studies have focused upon entrepreneurship as either an independent or a dependent variable. It has been suggested (Zahra, Jennings and Kuratko, 1999) that most firm-level studies have not examined the lag effect that might exist between antecedent variables and entrepreneurship. Additional research is, therefore, required focusing upon the causal sequences between entrepreneurship and outcomes (e.g., firm-level performance). Corporate venturing has

generally been depicted as an antecedent of company performance. Future studies should explore the link between company performance and subsequent corporate venturing behaviour. Longitudinal studies using quantitative as well as qualitative research methodologies would provide insights into the important why and how questions. In addition, given the problems that may arise where corporations have perspectives which are too short-term, and where there is inadequate continuing senior management support for corporate venturing activities, there remains a need for additional studies to address the barriers to corporate venturing.

Purchase of an Existing Organization: Management Buy-outs and Buy-ins Management buy-outs, where incumbent management purchase an existing organization in which they are employed, and management buy-ins, where outside managers effect a purchase of an existing organization with institutional finance, can both be considered as a form of corporate entrepreneurship. Studies have shown that the most significant contribution to organizational performance improvements emanate from managerial equity stakes rather than the commitment to servicing the debt used to finance the purchase of a business (Denis, 1994; Phan and

Hill, 1995). This latter finding suggests that entrepreneurial activities are taking place in these new organizational forms. The transfer of ownership in an existing firm is typically accompanied by entrepreneurial actions that reconfigure the way in which the firm operates (Malone, 1989), although buy-outs may not perform as well as owner-started businesses (Chaganti and Schneer, 1994). Wright, Thompson and Robbie (1992) showed that

although there has been a dominant agency cost perspective concerning buy-outs (Jensen, 1986), there is significant evidence of their entrepreneurial effects in the form of new product development and capital investment that would not otherwise have occurred. Zahra (1995) has also provided evidence of the entrepreneurial impact of management buy-outs. Wright, Wilson and Robbie (1996), for example, found that over a period of ten years following management buy-outs, new markets and product development were reported to be the most important influences on sales and profitability growth. The cognition perspective developed by Busenitz and Barney (1997) has opened up potentially interesting applications to the analysis of entrepreneurship in management buy-outs. Although it is possible to extend agency theory to apply to the design of incentives to encourage innovation in management buy-outs, this may be limited to the case of more routine innovation where incumbent managers rely on detailed information and systematic analyses in their decision-making. To achieve more radical innovation, there may be a need for individuals with an

entrepreneurial cognition orientation to adopt heuristic-based decision-making. Arguably, management buy-outs of divisions can occur where managers with an entrepreneurial cognition perspective become frustrated. For example, managers can be pushed into entrepreneurship by the bureaucratic decision-making process of a large diversified parent firm that rejects investment proposals because of a lack of the appropriate information to fit this process. Indeed, studies of managements motivation for buying out show the importance of being able to develop strategic opportunities that could not be carried out under the previous owners (Wright, Thompson, Chiplin and Robbie, 1991; Robbie, Wright and Albrighton, 1999), and to control their own destiny (Baruch and Gebbie, 1998). Further research is required to develop a clear theoretical and empirical analysis of the entrepreneurial dimension of management buy-outs. Wright, Hoskisson, Busenitz and Dial (2000) provide a step in this direction by developing a theoretical model that synthesizes the agency cost approach to buy-outs with a cognitive perspective. They argue that while the control and incentive mechanisms typically used in buy-outs can produce enhancements to efficiency and limited innovation, this will not lead to significant innovation, if the new-owner managers possess only managerial cognition since entrepreneurial cognition is required. There is a need to

empirically confirm the processes discussed above in a variety of industrial, national and cultural settings. Purchase of an Existing Organization: Franchising Franchising can be considered as an alternative start-up method and selected by some entrepreneurs concerned with minimizing uncertainty and risk. Several studies have focused upon the potential for co-operation versus conflict between the franchisee and the franchisor. Spinelli and Birley (1996) have presented an entrepreneurship

perspective surrounding franchising that provides insights into the informal governance of the relationship between the franchisor and the franchisee. Also focusing on relationship issues, Gassenheimer, Baucus and Baucus (1996) detected that participative communication generally enhanced franchisees freedom to take entrepreneurial actions. It has been suggested that an entrepreneur taking up a franchise is more likely to be associated with a firm that survives than an entrepreneur establishing a new independent firm (Shane, 1996). In marked contrast, Bates (1998), concluded that franchisees starting by purchasing the ongoing franchise unit from a previous owner were

riskier than franchisees starting from scratch, and indeed than de novo start-ups, since poor firm performance often lay behind the reason for the sale of the firm. Additional research surrounding the performance of outlets purchased by franchisees compared with other business ownership forms is warranted given conflicting empirical evidence. The control by the franchisor over the way franchisees organize their business (Felstead, 1994) raises issues about the ability of franchisees to engage in entrepreneurial actions. Despite growing recent interest in franchising, there appears to have been a general neglect of entrepreneurial issues associated with this context for entrepreneurship. Further research is required that considers the entrepreneurial attributes of individuals purchasing franchises, their search and opportunity recognition processes and the entrepreneurial actions they undertake. Inheritance of an Existing Organization: Family Firms Although there is no widely accepted family firm definition (Westhead and Cowling, 1998), several studies have detected that family firms differ from otherwise similar organizations because of the critical role that family members play in business processes at many levels (Davis and Harveston, 1998; Chua, Chrisman and Sharma, 1999). While the founding of a family firm fits with conventional definitions of entrepreneurship, the inheritance of an existing family firm raises issues about whether the inheritors engage in entrepreneurial behavior. Despite the importance of succession to the continuity of a family firm it is surprising to note that many issues of theoretical impact have not been explored in large-scale empirical studies (Davis and Harveston, 1998). Effective succession may be influenced by the objectives pursued by the family owning the business. Somewhat paradoxically, emphasis on the maintenance of a particular life-style objective (Westhead and Cowling, 1997) which involves family dominance in management (Daily and Dollinger, 1993) and family agendas (Church, 1993), can adversely affect a firms ability to adapt and survive in the long term. Quality of management may suffer (3i, 1995), captive boards may not bring the necessary pressure to change (Hoy and Verser, 1994), and there may be a reluctance to bring in outsiders who would contribute equity finance and monitoring (Westhead, 1997). The survival of family firms has been assisted by the development of management buy-outs where next-generation family owners are either not available or unwilling to take on the running of the business (Wright and Coyne, 1985). However, the frequent failure of family firms to develop professional non-family managers has meant that new outsiders may need to be brought in as the new owner-managers, creating a management buy-in (Robbie and Wright, 1996). Inheritors can also rid themselves of their burdens and responsibilities by the clean division of a family business into two or more separate independent businesses (Lansberg, 1999). On the other hand, the reported stronger commitment to long-term investments, greater focus upon the quality of their products or services (Westhead, 1997), and investment in employee and management training and / or research (Church, 1993; for a dissenting view see Westhead, 1997) may exert a positive influence on succession. Lansberg (1999) has recently presented a conceptual distinction between three types of succession transitions (i.e., succession transitions that recycle the business form; evolutionary successions that involve fundamental changes in the authority and control structure leading to a more complex family firm system; and devolutionary successions that lead to a more simpler family firm system). Further conceptual and rigorous empirical research on the entrepreneurial attributes of family firms facing succession issues is warranted. Given the lack of consensus as to what defines a family firm, additional studies need to examine carefully the entrepreneurial implications of succession in family and non-family firms. The succession issue clearly raises an urgent need for more longitudinal studies of family firms (Hoy and Verser, 1994). Additional research is required focusing upon the

true complexities of the succession process in the family firm (i.e., the three intertwined systems of the family, management and ownership) as well as the overlap between entrepreneurship and family business. The above discussion highlights that entrepreneurship may manifest itself in various organizational forms. There is a clear need to investigate the nature of entrepreneurial behavior within these different organizational settings. Furthermore, entrepreneurial actions and certain organizational forms may be considered more favorable in certain environments and cultural contexts (Shane, 1993). It follows, therefore, that investigation of the

entrepreneur and the organizational forms adopted (i.e., the entrepreneurial process), must be viewed in the context of the external environment. In the following section, the relationship between external environmental conditions and the nature of entrepreneurial activity is discussed.

THEME 5: EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENTS FOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP Van de Ven (1993) has argued that the study of entrepreneurship is deficient if it focuses exclusively on the characteristics and behaviors of individual entrepreneurs and treats the social, economic, and political infrastructure for entrepreneurship as externalities. He asserted that a social system perspective that considers external

environmental conditions is appropriate for explaining the process of entrepreneurship. A recent and growing body of research has focused upon venture creation and the relationship between environmental conditions and the nature of entrepreneurial activity (for a summary see Gnyawali and Fogel, 1994). Studies have explored the relationship between environmental conditions and new venture creation (Keeble and Walker, 1994; Reynolds, Storey and Westhead, 1994), business survival (Romanelli, 1989; Stearns, Carter, Reynolds and Williams, 1995), business closure (Keeble and Walker, 1994; Westhead and Birley, 1994), the competitive strategies pursued by organizations (Romanelli, 1989; Zahra, 1996) and business performance (Covin and Slevin, 1990; Vaessen and Keeble, 1995; Westhead and Wright, 1999). Resource dependence and population ecology theory have been used to guide research and provide explanations as to how the environment affects new firm formation rates. Resource dependence theorists view the environment as a pool of resources with organizations entering into transactional relationships with environmental factors because they cannot generate all necessary resources internally (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978). This theory suggests that differentiation and diversification encourage organizational survival and growth. The resource

dependence perspective is different from the population ecology perspective in that the organization is looked upon as more active in attempting to adapt to the environment. Adherents of the population ecology perspective suggest that the processes of carrying capacity, density, legitimation and competition play a determining role in the size of organizational populations (Hannan and Carroll, 1992). Within the evolutionary perspective, Aldrich (1990)

suggests that the founding of new organizations can be influenced by intra-population, inter-population and institutional factors. The predictive limitations of the population ecology perspective with regard to types of organizations established and their performance have been widely discussed (Romanelli, 1989; Aldrich, 1990; Bygrave and Hofer, 1991) and they still need to be addressed. In response to this research gap, Specht (1993) combined the population ecology and the resource dependence perspectives and presented a model of the relationship between organizational formation and environmental munificence and carrying capacity. Spechts novel model needs to be tested in a variety of environmental settings. Further, Specht has suggested that studies are required which focus upon

10

intervention methods to increase new formation rates in environments when munificence and carrying capacity are declining. Whilst not discounting internal managerial factors, Covin and Slevin (1989) explored the relationship between an organizations overall strategic orientation, its competitive tactics and the organizational attributes of firms in hostile and benign environments. Covin and Slevins study needs to be replicated in a variety of industrial and national settings beyond their sample of high performing small manufacturing firms. A longitudinal research design should be considered to unravel the business practices and organizational responses selected by entrepreneurs (and their firms) in hostile and benign environments. Further, the important why and how questions need to be explored using multivariate statistical techniques and qualitative methodologies. Additional research will provide useful evidence surrounding the causes of subsequent behavior reported by entrepreneurs competing in different types of external environments. Despite the contributions discussed above, Gnyawali and Fogel (1994) have argued that an integrated, theoretically driven and comprehensive framework is not available for studying the environmental conditions conducive for entrepreneurship. Moreover, they asserted that a conceptual framework is needed that integrates existing literature on external environments for entrepreneurship. Additional studies focusing upon this theme is, therefore, still warranted.

THEME 6: OUTCOMES The entrepreneurial process may lead to numerous outcomes. Most studies exploring the outcomes of

entrepreneurship have focussed on firm-level survival and / or financial performance. Focusing on firm-level aspects, while important, may be insufficient to understand fully the outcomes associated with the entrepreneurial phenomenon. It is possible to identify two additional dimensions of the entrepreneurial outcome: performance of the entrepreneur and firm exit issues. It is crucial, therefore, that any study exploring the outcome(s) of the entrepreneurial process is clear on the unit of analysis being used. To date, the majority of empirical work has used various objective financial and non-financial yardsticks to measure firm-level growth and performance (Birley and Westhead, 1990a; Chandler and Hanks, 1993; Cooper, 1993; Bridge, ONiell and Cromie, 1998). Entrepreneurial performance, however, may be a much more subjective concept, depending on the personal expectations, aspirations and skills of the individual entrepreneur. Whilst several studies have focused upon the personality and traits of entrepreneurs, the performance of entrepreneurs (i.e., the entrepreneur rather than the firm as the unit of analysis) has received limited research attention. Given the heterogeneous nature of entrepreneurship in terms of motivational diversity, different types of entrepreneurs and organizational forms, measuring entrepreneurial performance is inevitably a challenging task. Davidsson and Wiklund (this issue) and Venkataraman (1997) suggest that in order to distinguish what is truly attributable to the individual entrepreneur from the idiosyncrasies of the particular opportunity, the individuals must be studied across several new enterprise efforts. Rosa (1998) has called for a measure of entrepreneurial

performance in which aggregate value is assessed over all businesses owned by the entrepreneur, not just any single existing firm under study. Most notably, the performance of portfolio entrepreneurs should be assessed with reference to all the businesses they currently have an ownership stake in (Birley and Westhead, 1993a; Westhead and Wright, 1998a). Similarly, Davidsson and Wiklund (this issue) suggest that entrepreneurial career

11

performance in terms of the number and proportion of successful new enterprise processes or the total n et worth created, may be an effective means of avoiding the mismatch between independent and dependent variables (common in much entrepreneurship research). Many studies fail to appreciate the diversity of entrepreneurs and organizations owned by entrepreneurs. Consequently, very few studies have focussed upon which type of organization and which type of entrepreneur may influence several outcomes (Birley and Westhead, 1990a; Westhead, 1995). This diversity raises opportunities for entrepreneurship research in that there is a need to learn more about how type of entrepreneur or type of organization acts as a moderator in influencing relationships between predictors and performance (Chandler, 1996). Furthermore, to understand and separate the contribution of individual entrepreneurs (as well as teams of entrepreneurs) to the entrepreneurial process and entrepreneurial performance, qualitative approaches may be more appropriate. A final important outcome of the entrepreneurial process is the issue of firm exit (Birley and Westhead, 1990b). Defining organizational closure or failure is a major problem and a variety of definitions have been utilized (Keasey and Watson, 1991). There is no universally accepted definition of the point in time when an organization can be said to have closed (or failed). For example, the development of management buy -outs of companies in receivership suggests that although a firm may have failed in terms of one configuration of resources, it may be possible to resurrect it in another form (Robbie, Wright and Ennew, 1993). A detailed review of the small firm failure prediction literature by Keasey and Watson (1991) found that statistical models using firm-level data were able to predict the probability of firm closure better than human decision-makers using the same information sets. They believe that there may be a need to develop specific models for different types of firm failure. The major problem, however, is being able to obtain appropriate and representative samples of failed and non-failed firms. Brderl, Peisendorfer and Zeigler (1992) examined the contribution of human capital theory and organizational ecology explanations of new firm failure. Their analysis suggests that variables reflecting the latter approach, such as number of employees, capital invested and organizational strategies, are the most important determinants of firm survival. However, characteristics of the founder, notably years of schooling and work experience were also found to be important determinants. As noted earlier, the entrepreneurs decision to exit from the current business may not strictly be the result of failure or poor financial / economic performance. Ronstadt (1986) noted that 43% of businesses in his sample were exited due to liquidation. Interestingly, he found that 46% of the entrepreneurs in the sample exited by selling their businesses. Firm survival depends on an entrepreneurs own threshold of performance which is determined by human capital characteristics such as alternative employment opportunities, psychic income from entrepreneurship and the switching costs involved in moving to other occupations. (Gimeno et al., 1997). If economic performance falls below this threshold, the entrepreneur may exit the firm but continue in business if performance is above this threshold. However, if we accept the perspective that entrepreneurship relates largely to the recognition and exploitation of opportunities, it follows that opportunities may emerge at any time and in various forms. The option to exit from a firm may also be viewed as the exploitation of a strategic window of opportunity by the entrepreneur. Hence, the entrepreneur may choose to sell a firm if an attractive offer is put forward. Alternatively, the

entrepreneur may choose to exit a firm if a more appealing venture (i.e., opportunity) is accessible. There is a need, therefore, for additional research to explore the various reasons for exiting a firm and the modes of exit selected by entrepreneurs (Birley and Westhead, 1993b).

12

CONCLUSIONS This paper has highlighted that the focus of research into entrepreneurship. Most notably, several studies have recently given greater consideration to entrepreneurial behavior, search processes selected by different types of entrepreneur, the differing organizational forms through which entrepreneurial behavior is expressed and the importance of the external environment. The focus of future research should increasingly gather more information on wealth creation and the behavior of entrepreneurs and the patterns exhibited by entrepreneurs and their organizations in a variety of industrial, regional, national and cultural settings. As highlighted by Low and

MacMillan, there is a continued need for studies to explain the contexts and processes associated with entrepreneurial behavior. The following themes and links between themes are worthy of additional research as well as policy-maker and practitioner attention. 1. The theoretical antecedents explaining entrepreneurial behavior remain quite disparate (Theme 1 in Figure 1). Studies are required that attempt to integrate the inter-disciplinary nature of entrepreneurship. Although

complete integration may be unrealistic, recognition of the multi-disciplinary dimensions of entrepreneurship could add to our understanding of the phenomenon. 2. There is a growing appreciation of different types of entrepreneurs (i.e., nascent, novice, serial and portfolio entrepreneurs) as well as contrasting organizational forms selected (i.e., corporate venturing, management buyouts and buy-ins, franchising and family firms) by entrepreneurs. Despite recent progress, additional studies are required that focus upon the identification of different types of entrepreneurs (Theme 2). With respect to the links with theoretical antecedents, there is still a need to examine the heuristics adopted by different types of entrepreneurs with regard the differing contexts for entrepreneurship. For example, to what extent do novice entrepreneurs display different heuristics than serial and portfolio entrepreneurs (i.e., link between Themes 1 and 2)? Furthermore, depending on the heuristics and cognitive patterns displayed by entrepreneurs, the learning experiences from their ventures may be quite different (i.e., link between Themes 1 and 3). 3. Alongside the need to examine the heuristics of different types of entrepreneurs, there is scope to examine the cognitive behaviors of subgroups of entrepreneurs. For example, while habitual entrepreneurs may be different from novice entrepreneurs, habitual entrepreneurs among themselves may differ in terms of the number and quality of ventures they engage in (Theme 2). Further research is warranted that focuses upon the characteristics and motivations of those habitual entrepreneurs who appear to be addicted to entrepreneurship through their involvement in large numbers of ventures. To encourage best business practice, the skills accumulated and learnt by successful habitual entrepreneurs need to be identified and disseminated to nascent entrepreneurs as well as practicing entrepreneurs. With respect to the neglected area of entrepreneurial teams, there is a need for studies to explore the extent to which they can facilitate the acquisition and leveraging of resources. Further, given the diversity among entrepreneurs, studies should investigate whether certain contexts are more likely to be associated with a significantly lower probability of firm ownership and control in the hands of a single entrepreneur rather than a team of entrepreneurs. The following questions need to be carefully explored. What does each individual entrepreneur look for when they join a consortium of entrepreneurs to establish or purchase a business? What are the assets and liabilities provided by each entrepreneur involved in a business consortium? Do novice entrepreneurs tend to establish or purchase businesses with additional entrepreneurs as a means of overcoming their individual limited experience? Do habitual entrepreneurs make use of their broad networks to build better,

13

more effective firm ownership teams or do they over-rely on their own individual past experience? Are consortiums of entrepreneurs who establish new businesses different from consortiums of entrepreneurs who strategically select to purchase existing businesses? What are the problems and challenges facing each

entrepreneur involved in a business consortium? How does the composition and dynamics of ownership teams change in start-up ventures compared with purchased and inherited ventures? How does the composition and dynamics of ownership change in the successive ventures engaged in by habitual entrepreneurs? 4. Several studies have explored the opportunity recognition and information search processes exhibited by different types of entrepreneurs (Theme 3). Limited research has, however, been conducted focusing on how entrepreneurs use the knowledge they have acquired. For example, the learning issues embedded in the search behavior of serial and portfolio entrepreneurs are poorly understood (i.e., link between Themes 2 and 3). Research is needed to answer why, when and how certain individuals are able to identify and exploit opportunities, while others cannot or do not do so. For a number of entrepreneurs, one opportunity may present a whole array of shadow options (i.e., other potential opportunities). There is, therefore, scope to explore the extent to which certain types of entrepreneurs may adopt such an approach in evaluating opportunities (i.e., link between Themes 2 and 3). 5. There is further scope to examine the resource acquisition strategies selected by different types of entrepreneur (Theme 3). Studies are required that focus on how entrepreneurs leverage personal resources in order to create or acquire resources to diversify their firms resource base. Limited research has been conducted exploring the selection of appropriate competitive strategies by different types of entrepreneurs (and organizations) located in hostile and benign environments (i.e., link between Themes 2, 3 and 5). Studies need to be conducted that explore how different types of entrepreneurs may adopt different business related strategies. Research is also needed to examine the causal relationships between resources, strategies and organization and entrepreneur performance (i.e., link between Themes 2, 3 and 6). The resource-based view of the entrepreneur (and the firm) should be considered to guide studies in this area. 6. Additional studies are required that explore entrepreneurial behavior displayed in several contrasting organizational contexts (Theme 4). Studies are required to carefully examine, using multivariate statistical techniques as well as qualitative techniques, whether individuals involved in corporate entrepreneurship, management buy-outs and buy-ins, franchising or family firms exhibit different heuristics and cognitive behaviors from founders of independent start-up businesses or conventional managers (i.e., link between Themes 1 and 4). 7. Limited research has been conducted surrounding the search processes selected by purchasers or inheritors of businesses as well as individuals engaged in corporate venturing (i.e., link between Themes 3 and 4). Additional research is required to explore whether entrepreneurs in a management buy-out situation exhibit reactive behavior or do they proactively select a buy-out option after considering start-up and buy-in options. Studies should also explore whether certain types of organizational form create further profitable commercial opportunities for entrepreneurs. 8. Despite recent progress, the development and testing of an integrative model of the links between entrepreneurship and external environmental conditions is still required (Theme 5). Studies need to appreciate that contrasting environmental conditions exist for entrepreneurship. The emergence of market economies from former centrally planned economies, in particular, raises research possibilities for the study of entrepreneurial

14

heuristics and opportunity search processes in environments where entrepreneurship has previously been difficult, if not illegal. The change in environment to one in which the institutions of a market economy are either undeveloped or are missing, introduces the issue of whether entrepreneurship is either destructive (for example, organized crime and corruption) or constructive (Baumol, 1990). Moreover, studies need to focus on how to channel entrepreneurial talent and vision into more productive (i.e., constructive) activities rather than criminal and destructive activities. 9. The outcomes associated with the entrepreneurial process and context can be examined in terms of organizational or entrepreneurial performance (Theme 6). An expanding literature exists on organizational performance, for example, in terms of firm-level survival as well as sales, profits and employment growth. Unfortunately, this literature fails to adequately identify factors that explain subsequent firm-level performance, particularly the performance of independent start-ups businesses (Cooper, 1993; Storey, 1994). Additional studies are still urgently required focusing upon the relationships between the entrepreneur, the organization, the external environment and organizational performance in terms of financial and non-financial indicators (i.e., links between Themes 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). For example, do successful entrepreneurs subsequently become more reactive with regard to the search for opportunities or markets? Moreover, are successful entrepreneurs more likely to purchase rather than establish a subsequent business? Research exploring whether franchises are more likely to survive than independent start-up businesses are warranted. Studies need to recognize the importance of being consistent in terms of the unit of analysis being used, hence avoiding a mismatch between the independent and dependent variable (Davidsson and Wiklund, this issue). Further careful quantitative as well as qualitative studies of large longitudinal data-sets of entrepreneurs as well as organizations will enable researchers to shed greater light on the performance of different types of ventures. They will also provide policy-makers and practitioners with relevant information to develop more fine-tuned instruments to promote new firm formation and business development. Several studies have highlighted that some entrepreneurs own more than one business and have entrepreneurial careers. Additional research is warranted focusing upon the performance of entrepreneurs with regard to the portfolio of businesses that they own over time. The

performance of novice as well as habitual entrepreneurs should be measured with regard to their personal wealth, the quantity and quality of the businesses they own as well as the levels of satisfaction they report (i.e., link between Themes 2 and 6). Triangulation is required here to validate, revise and refine measures of entrepreneur-level as well as firm-level entrepreneurship. The themes highlighted above represent a considerable research agenda. It is clear that there is a need for further focus in entrepreneurship research surrounding context and process issues. These need to be examined in a far wider context than initially envisaged by Low and MacMillan. The emergence of newer entrepreneurial

organization forms, together with an appreciation that entrepreneurs may engage in more than one venture, takes the focus of future entrepreneurship research beyond the founding of new firms by first time entrepreneurs. Furthermore, examining the behavior of entrepreneurs through a cognitive and heuristic-based model is likely to aid our understanding of the entrepreneurial process.

15

References Aldrich, H. E. (1990). Using An Ecological Perspective to Study Organizational Founding Rates. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 14, 7-24. Alsos, G. A., and Kolvereid, L. (1998). The Gestation Process of Novice, Serial and Parallel Business Founders. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22, 101-114. Baron, R. A. (1998). Cognitive Mechanisms in Entrepreneurship: Why and When Entrepreneurs Think Differently Than Other People. Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 275-294. Baruch, Y., and Gebbie, D. (1998). Cultures of Success: Characteristics of the UKs Leading MBO Teams and Managers. Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 423-439. Bates, T. (1998). Survival Patterns Among Newcomers to Franchising . Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 113130. Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship, Productive, Unproductive and Destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 893-921. Birley, S. J. and Stockley, S. (2000). Entrepreneurial Teams and Venture Growth. In D. L. Sexton and H. Landstrm (Eds.), The Blackwell Handbook of Entrepreneurship. Oxford: Blackwell. Birley, S. J., and Westhead, P. (1990a). Growth and Performance Contra sts Between Types of Small Firms. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 535-557. Birley, S., and Westhead, P. (1990b). Private Business Sales Environments in the United Kingdom. Journal of Business Venturing, 5, 349-373. Birley, S., and Westhead, P. (1993a). A Comparison of New Businesses Established by 'Novice' and 'Habitual' Founders in Great Britain. International Small Business Journal, 12, 38-60. Birley, S., and Westhead, P. (1993b). The Owner-Managers Exit Route. In H. Klandt (Ed.). and Business Development, Avebury: Gower, 123-140. Entrepreneurship

Block, Z., and MacMillan, I. C. (1993). Corporate Venturing: Creating New Businesses within the Firm . Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Bridge, S., ONeill, K., and Cromie, S. (1998). Understanding Enterprise, Entrepreneurship & Small Business. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press Ltd. Brown, T. E., and Kirchhoff, B. A. (1997). Resource Acquisition Self-Efficacy: Measuring Entrepreneurs Growth Ambitions. In P. D. Reynolds, W. D. Carter, P. Davidsson, W. B. Gartner, and P. McDougall (Eds.). Frontiers in Entrepreneurship Research 1997, Wellesley, Massachusetts: Babson College, 59-60. Brderl, J., Preisendrfer, P., and Ziegler, R. (1992). Survival Chances of Newly Founded Business Organizations. American Sociological Review, 57, 227-242. Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G., Hart, M. M., and Edelman, L. F. (1997). Resource Configurations Over the Life Cycle of Ventures. In P. D. Reynolds, W. D. Carter, P. Davidsson, W. B. Gartner, and P. McDougall (Eds.). Frontiers in Entrepreneurship Research 1997, Wellesley, Massachusetts: Babson College, 315-329. Busenitz, L. W., and Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences Between Entrepreneurs and Managers in Large Organizations: Biases and Heuristics in Strategic Decision-Making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 9-30. Bygrave, W. D., and Hofer, C. W. (1991). Theorizing About Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16, 13-22. Carland, J. W., Hoy, F., Boulton, W. R., and Carland, J. AC. (1984). Differentiating Entrepreneurs from Small Business Owners. Academy of Management Review, 9, 354-359. Carrier, C. (1997). Intrapreneurship in Small Businesses: An Exploratory Study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21, 5-20.

16

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., and Reynolds, P. D. (1996). Exploring Start-Up Event Sequences. Journal of Business Venturing, 11, 151-166. Chaganti, R., and Schneer, J. A. (1994). A Study of the Impact of Owners Mode of Entry on Venture Performance and Management Patterns. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 243-260. Chandler, G. N. (1996). Business Similarity as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Pre-Ownership Experience and Venture Performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 20, 51-65. Chandler, G., and Hanks, S. H. (1993). Measuring the Performance of Emerging Businesses: A Validation Study. Journal of Business Venturing, 8, 391-408. Chandler, G., and Hanks, S. H. (1994). Market Attractiveness, Resource-Based Capabilities, Venture Strategies and Venture Performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 331-349. Chandler, G., and Hanks, S. H. (1998). An Examination of the Substitutability of Founders Human and Financial Capital in Emerging Business Ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 253-369. Chell, E., Haworth, J. M., and Brearley, S. A. (1991). The Entrepreneurial Personality: Concepts, Cases and Categories. London: Routledge. Christensen, P. S., Madsen, O. O., and Peterson, R. (1994). Conceptualising Entrepreneurial Opportunity Recognition. In G. E. Hills (Ed.), Marketing and Entrepreneurship: Research Ideas and Opportunities . Westport, CT: Quorum Books, 61-75. Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., and Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the Family Business by Behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 19-37. Church, R. (1993). The Family Firm in Industrial Capitalism: International Perspectives on Hypotheses and History. Business History, 35, 17-43. Cooper, A. C. (1993). Challenges in Predicting New Firm Performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 8, 241253. Cooper, A. C., and Dunkelberg, W. C. (1986). Entrepreneurship and Paths to Business Ownership. Strategic Management Journal, 7, 53-68. Cooper, A. C., Folta, T. B., and Woo, C. (1995). Entrepreneurial Information Search. Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 107-120. Cooper, A. C., Gimeno-Gascon, F. J., and Woo, C. Y. (1994). Initial Human and Financial Capital as Predictors of New Venture Performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 371-395. Covin, J. G., and Miles, M. P. (1999). Corporate Entrepreneurship and the Pursuit of Competitive Advantage. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 47-63. Covin, J. G., and Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10, 75-87. Cunningham, J. B., and Lischeron, J. (1991). Defining Entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 29, 45-61. Daily, C. M., and Dollinger, M. J. (1993). Alternative Methodologies for Identifying Family- Versus NonfamilyManaged Businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 31, 79-90. Davidsson, P., and Wiklund, J. (2000). Level of Analysis in Entrepreneurship Research Practice and Suggestions for the Future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, forthcoming.

17

Davis, P. S., and Harveston, P. D. (1998). The Influence of Family on the Family Business Succession Process: A Multi-Generational Perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22, 31-53. Delmar, F., and Davidsson, P. (2000). Where Do They Come From? Prevalence and Characteristics of Nascent Entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 12, 1-23. Denis, J. (1994). Organizational Form and the Consequences of Highly Leveraged Transactions: Krogers Recapitalization and Safeways LBO. Journal of Financial Economics, 36, 193-224. Dess, G, G., Lumpkin, G. T., and McGee, J. E. (1999). Linking Corporate Entrepreneurship to Strategy, Structure, and Process: Suggested Research Directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 85-102. Dyer, W. G. Jr. (1994). Toward a Theory of Entrepreneurial Careers. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19, 7-21. Ensley, M. D., Carland, J.C., Carland, J. W. and Banks, M. (1999): Exploring the Existence of Entrepreneurial Teams. International Journal of Management, 16, 276-286. Felsenstein, D. (1994). University-Related Science Parks - Seedbeds or Enclaves of Innovation? Technovation, 14, 93-110. Felstead, A. (1994). Shifting the Frontier of Control: Small Firm Autonomy Within a Franchise. International Small Business Journal, 12, 50-62. Fiet, J, Busenitz, L., Moesel, M., and Barney, J. (1997). Complementary Theoretical Perspectives on the Dismissal of New Venture Team Members. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 347-366. Floyd, S. W., and Wooldridge, B. (1999). Knowledge Creation and Social Networks in Corporate Entrepreneurship: The Renewal of Organizational Capability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 123-143. Flynn, D. M. (1993). A Critical Exploration of Sponsorship, Infrastructure, and New Organizations. Business Economics, 5, 129-156. Small

Gaglio, C. M. (1997). Opportunity Identification: Review, Critique and Suggested Research Directions. In J. A. Katz (Ed.), Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth . Connecticut: JAI Press, 3, 139202. Gartner, W. B. (1985). A Conceptual Framework for Describing the Phenomenon of New Venture Creation. Academy of Management Review, 10, 696-706. Gartner, W. B. (1990). What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 5, 15-28. Gartner, W. B., Bird, B. J., and Starr, J. A. (1992). Acting as if: Differentiating Entrepreneurial from Organizational Behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16, 13-31. Gassenheimer, J., Baucus, D., and Baucus, M. (1996). Cooperative Arrangements among Entrepreneurs: An Analysis of Opportunism and Communication in Franchise Structures. Journal of Business Research, 36, 6779. Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., and Woo, C. Y. (1997). Survival of the Fittest? Entrepreneurial Human Capital and the Persistence of Underperforming Firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 750-783. Gnyawali, D. R., and Fogel, D. S. (1994). Environments for Entrepreneurship Development: Key Dimensions and Research Implications. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18, 43-62. Greene, P. G., and Brown, T. E. (1997). Resource Needs and the Dynamic Capitalism Typology. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 161-173. Greene, P. G., Brush, C. G., and Hart, M. M. (1999). The Corporate Venture Champion: A Resource-Based Approach to Role and Process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 103-122.

18

Guth, W. D., and Ginsberg, A. (1990). Guest Editors Introduction: Corporate Entrepreneurship. Management Journal, 11 (special issue), 5-15.

Strategic

Hannan, M. T., and Carroll, G. R. (1992). Dynamics of Organizational Populations: Density, Legitimation and Competition. New York: Oxford University Press. Hart, M., Greene, P. G., and Brush, C. G. (1997). Leveraging Resources: Building and Organization on an Entrepreneurial Resource Base. In P. D. Reynolds, W. D. Carter, P. Davidsson, W. B. Gartner, and P. McDougall (Eds.). Frontiers in Entrepreneurship Research 1997. Wellesley, Massachusetts: Babson College, 347-348. Hills, G. E., Lumpkin, G. T and Singh, R. P (1997). Opportunity Recognition: Perceptions and Behaviors of Entrepreneurs. In P. D. Reynolds, P. W. D. Carter, P. Davidsson, W. B. Gartner, and P. McDougall (Eds.). Frontiers in Entrepreneurship Research 1997, Wellesley, Massachusetts: Babson College, 330-344. Hitt, M. A., Nixon, R. D., Hoskisson, R. E., and Kochhar, R. (1999). Corporate Entrepreneurship and CrossFunctional Fertilization: Activation, Process and Disintegration of a New Product Design Team. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 145-167. Hornaday, R. W. (1990). Dropping the E-words from Small Business Research. Journal of Small Business Management, 28, 22-33. Hoy, F., and Verser, T. G. (1994). Emerging Business, Emerging Field: Entrepreneurship and the Family Firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19, 9-23. Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance and Takeovers. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings May, 76, 326-329. Johannisson, B., Alexanderson, O., Nowicki, K., and Senneseth, K (1994). Beyond Anarchy and Organization: Entrepreneurs in Contextual Networks. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 6, 329-356. Johnston, R. J. (1991). A Question of Place: Exploring the Practice of Human Geography . Oxford: Blackwell. Kaish, S., and Gilad, B. (1991). Characteristics of Opportunities Search of Entrepreneurs Versus Executives: Sources, Interests, General Alertness. Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 45-61. Kamm, J. B., and Shuman, J. C. (1990). Entrepreneurial Teams in New Venture Creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 14, 7-24 Katz, J. A. (1994). Modelling Entrepreneurial Career Progressions: Concepts and Considerations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19, 23-39. Keasey, K., and Watson, R. (1991). The State of the Art of Small Firm Failure Prediction: Achievements and Prognosis. International Small Business Journal, 9, 11-29. Keeble, D., and Walker, S. (1994). New Firms, Small Firms, and Dead Firms: Spatial Patterns and Determinants in the United Kingdom. Regional Studies, 28, 411-427. Kirzner, I. M. (1973). Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Lansberg, I. (1999). Succeeding Generations: Realizing the Dream of Families in Business . Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press. Boston,

Low, M. B., and MacMillan, I. C. (1988). Entrepreneurship: Past Research and Future Challenges. Journal of Management, 35, 139-161. Lumpkin, G. T., and Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking it to Performance. Academy of Management Review, 21, 135-172.

19

Malone, S. (1989). Characteristics of Smaller Company Leveraged Buyouts. Journal of Business Venturing, 4, 349-359. Manimala, M. J. (1992). Entrepreneurial Heuristics: A Comparison Between High PI (Pioneering-Innovative) and Low PI Ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 7, 477-504. McGrath, R. G. (1999). Falling Forward: Real Options Reasoning and Entrepreneurial Failure. Academy of Management Review, 24, 13-30. McGrath, R. G., Venkataraman, S., and MacMillan, I. C. (1994). The Advantage Chain: Antecedents to Rents from Internal Corporate Ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 351-369. Mosakowski, E. (1993). A Resource-Based Perspective on The Dynamic Strategy-Performance Relationship: An Empirical Examination of the Focus and Differentiation Strategies in Entrepreneurial Firms. Journal of Management, 19, 819-839. Murray, G. (1994). The Second Equity Gap: Exit Problems for Seed and Early Stage Venture Capitalists and their Investee Companies. International Small Business Journal, 12, 59-76. Palich, L. E., and Bagby, D. R. (1995). Using Cognitive Theory to Explain Entrepreneurial Risk-Taking: Challenging Conventional Wisdom. Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 425-438. Pfeffer, J., and Salancik, G. R. (1978). The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper & Row. Phan, P., and Hill, C. (1995). Organizational Restructuring and Economic Performance in Leveraged Buyouts: An Ex Post Study. Academy of Management Review, 38, 704-739. Reynolds, P. D. (1997). Who Starts New Firms? - Preliminary Explorations of Firms-in-Gestation. Small Business Economics, 9, 449-462. Reynolds, P. D., Storey, D. J., and Westhead, P. (1994). Cross-National Comparisons of the Variation in New Firm Formation Rates. Regional Studies, 28, 443-456. Robbie, K., and Wright, M. (1996). Management Buy-Ins: Active Investors and Corporate Restructuring . Manchester: Manchester University Press. Robbie, K., Wright, M., and Ennew, C. (1993). Management Buy-outs from Receivership. Omega, International Journal of Management Science, 21, 519-530. Robbie, K., Wright, M., and Albrighton, M. (1999). High Tech Management Buy-outs. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 1, 219-240. Romanelli, E. B. (1989). Environments and Strategies of Organization Start-Up: Effects on Early Survival. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34, 369-387. Ronstadt, R. (1986). Exit, Stage Left: Why Entrepreneurs End Their Entrepreneurial Careers Before Retirement. Journal of Business Venturing, 1, 323-338. Ronstadt, R. (1988). The Corridor Principle. Journal of Business Venturing, 3, 31-40. Rosa, P. (1998). Entrepreneurial Processes of Business Business Cluster Formation and Growth by Habitual Entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22, 43-61. Russell, R. D. (1999). Developing a Process Model of Intrapreneurial Systems: A Cognitive Mapping Approach. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 65-84. Sapienza, H. J., Manigart, S., and Vermeir, W. (1996). Venture Capitalists Governance and Value Added in Four Countries. Journal of Business Venturing, 11, 439-469.

20

Shane, S. (1993). Cultural Influences on National Rates of Innovation. Journal of Business Venturing, 8, 59-73. Shane, S. A. (1996). Hybrid Organizational Arrangements and their Implications for Firm Growth and Survival: A Study of New Franchisors. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 216-234. Shane, S., and Venkataraman, S. (2000). The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. Academy of Management Review, 25, 217-226. Sharma, P., and Chrisman, J. J. (1999). Toward a Reconciliation of the Definitional Issues in the Field of Corporate Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 11-27. Slevin, D. P., and Covin, J. G. (1992). Creating and Maintaining High-Performance Teams. In D. L. Sexton and J. D. Kasarda (Eds.) The State of the Art of Entrepreneurship. Boston, MA: PWS-Kent Publishing Company, 358-386. Specht, P. H. (1993). Munificence and Carrying Capacity of the Environment and Organizational Formation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17, 77-86. Spinelli, S., and Birley, S. (1996). Towards a Theory of Conflict in the Franchise System. Journal of Business Venturing, 11, 329-342. Stearns, T. M., Carter, N. M., Reynolds, P. D., and Williams, M. L. (1995). New Firm Survival, Industry, Strategy, and Location. Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 23-42. Stevenson, H. H., and Gumpert, D. E. (1985). The Heart of Entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 63, 8594. Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the Small Business Sector. London: Routledge. 3i. (1995). The 3i / Mori Survey of Key Independent Businesses in Britain . London, 3i. Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 509-533. Thrift, N. (1996). Spatial Formations. London: Sage Publications. Tversky, A., and Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185, 11241131. Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., Robbie, K., and Westhead, P. (1999). Habitual Entrepreneurs: A Resource-Based View. Paper presented at the Ninth Global Entrepreneurship Conference , New Orleans, April 1999. Vaessen, P., and Keeble, D. (1995). Growth-Orientated SMEs in Unfavourable Regional Environments. Regional Studies, 29, 489-505. Van de Ven, A. H. (1993). The Development of an Infrastructure for Entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 8, 211-230. Venkataraman, S. (1997). The Distinctive Domain of Entrepreneurship Research. In J. A. Katz (Ed.), Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth. Connecticut: JAI Press, 3, 139202. Westhead, P. (1995). Survival and Employment Growth Contrasts Between Types of Owner-Managed HighTechnology Firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 20, 5-27. Westhead, P. (1997). Ambitions, 'External' Environment and Strategic Factor Differences between Family and Non-Family Companies. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 9, 127-157. Westhead, P., and Batstone, S. (1999). Perceived Benefits of a Managed Science Park Location for Independent Technology-Based Firms. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 11, 129-154.

21

Westhead, P., and Birley, S. (1994). Environments for Business Deregistrations in the United Kingdom, 19871990. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 6, 29-62. Westhead, P., and Cowling, M. (1997). Performance Contrasts Between Family and Non-Family Unquoted Companies in the UK. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research , 3, 30-52. Westhead, P., and Cowling, M. (1998). Family Firm Research: The Need for a Methodological Rethink. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 31-56. Westhead, P., and Storey, D. J. (1995). Links Between Higher Education Institutions and High Technology Firms. Omega, International Journal of Management Science , 23, 345-360. Westhead, P., and Wright, M. (1998a). Novice, Portfolio, and Serial Founders: Are They Different? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 173-204. Westhead, P., and Wright, M. (1998b). Novice, Portfolio, and Serial Founders in Rural and Urban Areas. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22, 63-100. Westhead, P., and Wright, M. (1999). Contributions of Novice, Portfolio, and Serial Founders Located in Rural and Urban Areas. Regional Studies, 33, 157-173. Westhead, P., and Wright, M. (2000). Introduction. In P. Westhead and M. Wright (Eds.), Advances in Entrepreneurship. Volume 1, xi-xcvi. Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, (forthcoming). Woo, C. Y., Cooper, A. C., and Dunkelberg, W. C. (1991). The Development and Interpretation of Entrepreneurial Typologies. Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 93-114. Woo, C. Y., Folta, T., and Cooper, A. C. (1992). Entrepreneurial Search: Alternative Theories of Behavior. In N. C. Churchill, S. Birley, W. D. Bygrave, D. F. Muzyka, C. Wahlbin, and W. E. Wetzel (Eds.) Frontiers in Entrepreneurship Research 1992, Wellesley, Massachusetts: Babson College, 31-41. Wright, M., and Coyne, J. (1985). Management Buy-outs. Beckenham: Croom Helm. Wright, M., Hoskisson, R., Busenitz, L., and Dial, J. (2000). Entrepreneurial Growth Through Privatization: The Upside of Management Buy-outs. Academy of Management Review, forthcoming . Wright, M., Robbie, K., and Ennew, C. (1997). Venture Capitalists and Serial Entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 227-249. Wright, M., Robbie, K., Thompson, S., and Starkey, K. (1994). Longevity and the Life-cycle of Management Buyouts. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 215-228. Wright, M., Thompson, S., Chiplin, B., and Robbie, K. (1991). Management Buy-ins and Buy-outs: New Strategies in Corporate Management. London: Graham & Trotman. Wright, M., Thompson, S., and Robbie, K. (1992). Venture Capital and Management-Led, Leveraged Buy-Outs: A European Perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 7, 47-71. Wright, M., Westhead, P., and Sohl, J (1998). Habitual Entrepreneurs and Angel Investors. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22, 5-21. Wright, M., Wilson, N., and Robbie, K. (1996). The Longer Term Effects of Management-led Buyouts. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Small Business Finance, 5, 213-234. Zahra, S. A. (1991). Predictors and Outcomes of Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 259-285. Zahra, S. A. (1993). Environment, Corporate Entrepreneurship, and Financial Performance: A Taxonomic Approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 8, 319-340.

22