Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dissociation, The True Self and The Notion of The Frozen Baby

Uploaded by

Albert Muya MurayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dissociation, The True Self and The Notion of The Frozen Baby

Uploaded by

Albert Muya MurayaCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] On: 16 April 2010 Access details: Access Details:

[subscription number 791536623] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 3741 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Psychodynamic Practice

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713735392

Dissociation, the true self and the notion of the frozen baby

Maria Papadima a a Department of Psychosocial Studies, University of East London, UK

To cite this Article Papadima, Maria(2006) 'Dissociation, the true self and the notion of the frozen baby', Psychodynamic

Practice, 12: 4, 385 402

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/14753630600958189 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14753630600958189

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Psychodynamic Practice, November 2006; 12(4): 385 402

Dissociation, the true self and the notion of the frozen baby

MARIA PAPADIMA

Department of Psychosocial Studies, University of East London, UK

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Abstract The widespread trauma talk that is prevalent in the social sciences, has, in recent years, become increasingly commonplace in psychoanalytic writings, especially in attachment theory and relational psychoanalysis. This paper examines dissociation, a key concept in trauma theory, in conjunction with the Winnicottian term true self, in the context of a particular discursive and theoretical combination of the two. This discursive formation is named the frozen baby discourse, and it is presented and analysed. A critique is offered of the way true self, understood as a humanistic concept, is often used together with dissociation, in order to create a theoretical construct that is far removed from Winnicottian theory. This paper begins by exploring denitional issues, both around dissociation and true self. It is subsequently argued that this contemporary usage of true self in combination with dissociation has important implications for psychoanalytic practice.

Keywords: True self, dissociation, psychoanalysis, Winnicott, trauma.

Introduction In this paper, I will examine the Winnicottian term true self, and the way in which it forms a discursive basis for a modern, and currently fashionable, psychoanalytic understanding of dissociation, frequently found in attachment theory and relational psychoanalysis. I will start by looking at the concept of dissociation in its use within certain contemporary psychoanalytic texts, mainly belonging to the relational and attachment traditions. I will then look at how Winnicotts true self is employed in the context of this conceptualization. I will argue that the combination of the two terms creates a new way of understanding psychic trauma, which is far removed from the inspiration behind Winnicotts work, as indeed it is far removed from Freudian theory.

Correspondence: Maria Papadima, 6 Vaughan House, Nelson Square, London SE1 0PY. E-mail: maria.papadima@yahoo.com ISSN 1475-3634 print/ISSN 1475-3626 online 2006 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/14753630600958189

386

M. Papadima

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Winnicotts writing is rich, hard to grasp and complex. At the same time, paradoxically, it is characterized by a misleading simplicity or straightforwardness, which perhaps explains some of the theoretical confusions and divergences that often are found in readings of his work. Indeed, it can be argued that the strength and, simultaneously, weakness of Winnicottian concepts, including the term true self, is exactly that they can be read in many ways. True self is exible and slippery, a one-size-ts-all kind of concept, at least at rst glance. One inescapable association that leads to a widespread misreading of true self is understanding it as a humanistic core self deep inside us all, reminiscent of Rogerian conceptualizations of selfhood. This is precisely the reading of true self on which a popular current psychoanalytic understanding of dissociation depends. True self can thus be seen as a fertile battleground on which wider psychoanalytic debates on trauma and dissociation are played out. These theoretical battles do not occur, of course, in obvious ways, since it is not always easy to identify how different psychoanalytic authors position themselves within them. Different views and takes on the matter can be identied, often, merely by the casual and good-natured mention of true self in a context where it arguably does not belong. The way notions such as dissociation and true self as with all important concepts are employed implies certain assumed consequences of this, rather than another, use. Consequently, dissociation and true self in their particular combination that will be examined in this paper serve as a good example of where the authors using them wish to take us; and which psychoanalytic paths they want us to leave behind. I will begin by looking at the recent vicissitudes of the term dissociation within psychoanalytic theory, and I will then examine how Winnicotts true self is discursively and theoretically understood in that context. Dissociation and psychoanalysis In recent years, increasing attention has been devoted in psychoanalytic theorizing to rethinking the notion of trauma as it refers to a real, tangible, externally inicted event and its effects on later personality development. This emphasis on trauma and, more broadly, on traumatic memory is not specic to psychoanalysis (Fonagy & Target, 1995) and indeed it has been noted that less work has been done on understanding trauma and resulting dissociative states from a psychoanalytic viewpoint than has been done in other elds (Fonagy & Target, 1995, p. 161). Memory has become a central and organising concept within the social sciences in the last 30 years (Radstone, 2000b, p. 3), and trauma is the preferred theoretical framework in this discussion, stressing what has been called the toxicity of the event (Radstone, 2000a, p. 88). In psychoanalysis, a growing number of writings follow in this toxic event tradition,

Dissociation and the true self

387

frequently making use of the term true self in its aforementioned humanistic slant, even though Freuds (and, as will be argued, Winnicotts) work is a theory of conict and is fundamentally anti-humanist. For the purposes of this paper, I will refer to those psychoanalytic theoreticians who draw attention to the toxic event as the trauma paradigm writers.1 Dissociation, in the trauma paradigm literature, has become a key conceptual building block, mainly in its link to a specic, objectively documentable traumatic event.2 This theoretical turn towards a traumatic dissociation/hidden-true self model is worth looking at more closely since it is relatively recent within psychoanalytic circles. The transition, since the 1970s, from the prevailing unconscious conict model to the trauma paradigm is well documented, regardless of whether it is considered a positive or negative move (Bromberg, 1996a; Mollon, 1998b; Eagle, 2000, p. 126; Leys, 2000; Hinshelwood, 2002; Midgley, 2002, p. 38). The wider account of how dissociation has come to be understood as it is today is also well documented it is a term rst used by the nineteenth century French psychiatrist Pierre Janet (Hacking, 1995, p. 44; LeBlanc, 2001), largely forgotten for the biggest part of the twentieth century and gradually rediscovered in large part in the context of the second-wave feminist movements interest in sexual violence, and also with the re-introduction of Janets work (1889) through Henri Ellenbergers book The discovery of the unconscious, published in 1970 (van der Kolk & van der Hart, 1995, p. 159, Ellenberger, 1970). As for the link to psychoanalysis, Ian Hacking points out that the term dissociation used to be seen as indisputably far removed from the psychoanalytic framework the two models being in confrontation (Hacking, 1995, p. 134) until recently. This theoretical dissimilarity and this historical confrontation is now often offhandedly ignored, as a considerable number of writers who position themselves within psychoanalysis, mainly attachment theorists and relational psychoanalysts, make use of the concept of dissociation and see no contradiction in doing so. It is important then to examine the work of these writers and the ensuing theoretical debate around dissociation and the hidden true self in order to see what, if any, are the reasons for emphasizing it as a core psychic mechanism that helps to understand traumatic processes. One debate around dissociation, or two debates around dissociation? What can be observed when looking at the use of dissociation is that there are actually two very different conceptualizations of it in psychoanalytic theory, one based on early Freud and one on late Freud. There are not one but two psychoanalytic debates on dissociation, and frequently the two become conated.

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

388

M. Papadima

The rst debate around dissociation refers to pre-Freudian works, and in particular to Pierre Janets work (Janet, 1889), which emphasizes the idea of split consciousness, the centrality of a specic traumatic event and the importance of abreaction. It also refers to Freuds early understanding of the term, in particular in Studies on hysteria (Freud & Breuer, 1895) as well as in earlier papers. This rst conceptualization has followed its own path, predominantly outside psychoanalysis, and has only recently been picked up by certain psychoanalytic writers.3 There is however a second debate around dissociation within Freuds own work. This can more accurately be described as a progressive conceptualization of two novel terms, splitting and disavowal, which are gradually built up out of his early use of dissociation.

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Dissociation In the psychoanalytic dictionary of Laplanche and Pontalis (1986) the term dissociation is not included. It also is not included in Hinshelwoods Kleinian dictionary (1991), nor in Dylan Evanss Lacanian dictionary (2001). In Freuds own work, dissociation as such is mentioned very few times, mainly in the context of early considerations, especially referring to Janets work (Richards, 1974, p. 266). All these dictionaries, however, refer extensively to splitting (Spaltung), as well as to disavowal (Verleugnung), and these two terms have taken the place of dissociation. The question is whether splitting and disavowal as utilized by Freud have anything to do with dissociation as utilized by Janet and the very early Freud. Disavowal The term splitting (Spaltung) is very closely linked to disavowal (Verleugnung) found in a few of Freuds papers (Freud, 1918, p. 85; Freud, 1923; Freud, 1925; Freud, 1927; Freud, 1938a). Disavowal is used by Freud to denote a specic mode of defence which consists in the subjects refusing to recognise the reality of a traumatic perception (Laplanche & Pontalis, 1986, p. 61), and it is a term linked both to psychosis and to fetishism (Evans, 2001, p. 43) and, more crucially, to castration. Lacan and subsequent Lacanian psychoanalysts have taken up the term and have provided a rigorous theory of disavowal, linking it to perversion and differentiating it from foreclosure (in psychosis) and repression (in neurosis) (Evans, 2001). Like Freud, Lacan asserts that disavowal is always accompanied by a simultaneous acknowledgment of what is disavowed. Thus the pervert is not simply ignorant of castration; he simultaneously knows it and denies it (Evans, 2001, p. 44). When Freud re-introduces the concept splitting of the ego in his fetishism paper (Freud, 1927) he is doing so in order to better understand the

Dissociation and the true self

389

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

simultaneous and unconscious knowing and not knowing of castration, and it is unclear in this point in his writing what the term splitting refers to, as separate from repression (Laplanche & Pontalis, 1986, p. 62). Perhaps Freud is referring to disavowal. It is, however, apparent that the simultaneous existence of separate states of consciousness as conceptualized in the pre-Freudian (Janetian) and early Freudian works, is far from the idea he is here grappling with. He is more importantly asking questions about the nature of subjectivity and the nature of the self. Even though the term splitting is widened in Freuds paper (1938b), as well as in the Outline of psychoanalysis of the same year (1938a), still, he principally keeps it linked to psychosis and fetishism (Evans, 2001, p. 192). It is thus very hard to make the argument that this concept belongs to the aforementioned rst debate on dissociation and splitting, the debate based on Janets and earlyFreudian writings. Splitting In introducing the term, Laplanche and Pontalis (1986) do make an historical link to the pre-Freudian/early Freudian work on hysteria, hypnosis, multiple personality and splitting of consciousness (bewusstseinsspaltung, Freud & Breuer, 1895). At that early stage Freud explicitly refers to dissociation and examines hysteria on the terms set out by the theoreticians before him, including Bleuler and Janet. In that context, Freud sees hysterical dissociation as a form of personality split. However, by introducing the concept of the unconscious and that of psychic conict, a move that can be traced in Studies on hysteria, Freud irreversibly moves away from Janets, Bleulers and even Breuers ideas, giving birth to an original, new theory, that of the unconscious. What can be surmised from this initial use of the term dissociation is that Freud, in discovering and shaping this new object of study, the unconscious,4 had to think his discovery and his practice in imported concepts borrowed from the then dominant energy physics, political economy, and biology of his time (Althusser, 1964, p. 16). We can include dissociation and splitting to this list of borrowed concepts which Freud imported from Janets work and used in an increasingly differentiated sense, making the concepts his own, and quickly discarding Janets original use of them. In this way, Freud was gradually able to create his own domestic concepts (Althusser, 1964). In any case, the term splitting is used only sporadically in Freuds subsequent work and is not a foundational concept (Laplanche & Pontalis, 1986, p. 136). Yet, as we saw above, it is true that Freud returns to it from time to time, particularly in his late papers, showing that this term became of fundamental importance towards the end of his life (Freud, 1937, 1938a, b). What is important for the purposes of this paper is to demonstrate that the

390

M. Papadima

terms of the second debate, that on splitting as outlined in Freuds late work, have little to do with the terms of the non-psychoanalytic terms of the rst debate, that of dissociation as based in Janets work. Turning back the clock It is often the case that writers referring to Freuds 1938b paper on splitting make an explicit or implicit link to his early, Janetian, use of dissociation, implying that there is a turning back to his earlier understanding of the term, which emphasized the idea of a radical split consciousness. One early example of this confusion can be found in one of Stracheys editorial comments, which is ambiguous and can be read in different ways. Strachey, in his editors note on Freuds splitting paper, does indeed link the early and late uses of splitting and dissociation. He considers the topic of the 1938b paper on splitting in connection to the wider question of the alteration of the ego which is invariably brought about by the processes of defence (Strachey, 1964, p. 274) and he connects this theoretical development to Freuds Outline of psychoanalysis (Freud, 1938a) and Analysis terminable and interminable (Freud, 1937), noting that this discussion leads us back to very early times, to the second paper on the neuropsychoses of defence . . . and to the even earlier Draft K of the Fliess correspondence (Strachey, 1964, p. 274). This is where the misunderstanding may begin, since the trauma paradigm writers can perhaps infer from this statement that Strachey sees the splitting paper as a return to the terms of the rst debate on dissociation. This is in fact far from Stracheys point. What can be understood from his observation is that there is a topic that Freud returns to again and again, that of the self as fundamentally, irreducibly split, with no possibility of achieving wholeness or integration. It is not by chance that Strachey refers to Analysis terminable and interminable, a paper far from optimistic in a humanistic, discovering the long-lost integration within us kind of way. The idea of cure or even of denite psychic progress that is to be found in Studies on hysteria is forever gone by 1937. The term splitting in Freuds nal papers refers to a general characteristic of subjectivity itself; the subject can never be anything other than divided, split, alienated from himself. The split is irreducible, can never be healed; there is no possibility of synthesis (Evans, 2001, p. 192). When returning then to his earlier musings on dissociation, conceptualized as splitting, Freud does not of course forget the path he has trodden, nor does he go back to Janets work. Rather, he recalls his initial idea of splitting caused by a specic, externally generated traumatic event which leads to hysteria and widens it to show that trauma is inherent in each persons life and has to do with castration, understood at this point as a widened concept.

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Dissociation and the true self

391

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

In fact, one main difference between splitting in Freuds 1938 paper and splitting of consciousness (that is, the early understanding of dissociation) in Studies on hysteria has to do with the importance of castration, and the splitting paper certainly is part of a series of Freudian works dealing explicitly with this issue. Considering castration in Lacanian terms, what is split off (disavowed) is the realisation that the cause of desire is always a lack (Evans, 2001, p. 44) and not the particular perception of lack of penis in women. In this understanding of Freuds term, there can be no humanistic concept of a self made whole after recalling and reliving a trauma, an idea at the heart of the rst dissociation debate and taken up by trauma paradigm writers. The self cannot be made whole because it was never whole to begin with, but is fundamentally split, right at its centre. This point is also at the heart of the misreading of Winnicotts true self, when seen as a dissociated and hidden but, at the same time, whole and intact part of the personality. Dissociation and the trauma paradigm It is then possible to conclude that dissociation is habitually used, by certain psychoanalysts, in the pre-Freudian/early-Freudian way, as found partially in Studies on hysteria, and mainly in Janets work. In the trauma paradigm writing this understanding of dissociation is often cemented by referring to Winnicotts true self, in order to demonstrate what is dissociated, and what analysis aims to retrieve and restore. Namely, in trauma paradigm writings, both dissociation and true self are used in the terms of the rst debate on dissociation. What follows is a brief overview of such writings on dissociation. I begin with attachment theory, followed by relational psychoanalysis.5 These theories have in common a rejection of Freudian drive theory and its focus on sexuality, an emphasis on the centrality of relatedness (Mills, 2005, p. 157) as different from the alleged classical Freudian and Lacanian emphasis on a one-person psychology, and an increasing emphasis on trauma and its consequences, including dissociation. Attachment and dissociation Attachment theory, which historically belongs to the psychoanalytic tradition, yet has always had a fraught relationship with it (Fonagy, 2001; Diamond, 2004, p. 277), takes dissociation, in the terms of the rst debate, very seriously. One main nding is that dissociation is primarily linked to disorganized/disoriented attachment, as it manifests itself both in children and in their adult caregivers (Alexander, 1992; Liotti, 1992; Carlson & Sroufe, 1995, p. 607; Fonagy, 2001, pp. 32, 43, Fonagy, 2002, p. 74; Southgate, 2002). The central idea is that dissociation becomes a psychic way of coping for people who have experienced disorganized/disoriented

392

M. Papadima

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

relations with their main attachment gures. Dissociation is seen as an extreme coping mechanism, especially in cases of abuse or maltreatment from which the child needs to psychically escape: Through the process of dissociation, or defensive exclusion of information, the child . . . attempts to defend against severe trauma or loss (Alexander, 1992, p. 191). Indeed, the connection between dissociation, abuse or maltreatment and disorganized/disoriented attachment is a consistent nding in this literature (Diamond, 2004, p. 280). Importantly, intergenerational transmission of unresolved trauma would also be considered as possibly leading to dissociation and/or disorganized/disoriented attachment (Fonagy & Target, 1995, p. 164; Diamond, 2004, p. 280), widening considerably the scope of how trauma is to be conceived. The goal of therapy, apparently, is to relive the initial traumatic relationship in the context of the transference, and to rebuild a long-lost but certainly pre-existing cohesion, taking Michael Balints ideas on the basic fault (1979) a step further. Relational psychoanalysis and dissociation A number of recent writers from the American relational psychoanalytic tradition take a strikingly similar viewpoint. Indeed, in an introductory collection on relational psychoanalysis, dissociation gures largely in the subject index (Mitchell & Aron, 1999, p. 497) and is strictly used in the terms of the rst debate. Castration does not appear in the same subject index, while splitting gets only two meagre references (Mitchell & Aron, 1999, p. 511). This body of work, which follows partly from the British object-relational tradition, focuses on dissociation as a concept worth theorizing in its own right, separate from repression, splitting or other concepts. Philip Bromberg explains the changes that he understands to be occurring within psychoanalytic theory: Because of the increased attention now being paid to the normal multiplicity of states of consciousness, an important shift is taking place that is leading away from the unconscious-preconscious-conscious continuum per se, toward a view of the mind as a conguration of discontinuous, shifting states of consciousness with varying degrees of access to perception and cognition. Some of these self-states are hypnoidally unlinked from perception at any given moment of normal mental functioning not unlike some of Freuds ideas in his Project and The Interpretation of Dreams, while other self-states are virtually foreclosed from such access because of their original lack of linguistic symbolization (Bromberg, 1996a, p. 58). Bromberg therefore sees psychoanalysis as returning to the terms of the rst debate on dissociation, namely, as returning to a pre-Freudian

Dissociation and the true self

393

conceptualization of subjectivity. In the relational psychoanalytic tradition it is increasingly common to come across similar papers which take dissociation for granted and show how it can be utilized clinically (Messler Davies, 1996; Bromberg, 1998; Brenner, 1999; Waugaman, 2000; Brenner, 2001; Burton & Lane, 2001; Laub, 2003). Taking these notions a step further, there is also a theoretical move towards theorizing the self in terms of multiplicity (Messler Davies, 1996; Slavin, 1996; Chefetz & Bromberg, 2004; Arnold, 2005), naming this the multiple self-state model (Bromberg, 1996b; Chefetz & Bromberg, 2004), or the normal multiplicity of self (Bromberg, 1996b). The frozen baby discourse

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Following from the above overviews, it becomes clear that trauma paradigm writers understand dissociation in a particular way. Phil Mollon, a leading trauma paradigm spokesman, and a practising psychoanalyst, explains that dissociation is almost a state of auto-hypnosis. It refers, for instance, to a child during abuse thinking: I am not here, this is not happening to me (Mollon, 1998b, p. 134). This representation of dissociation assumes a radical separation between the self who understands and witnesses what is going on, and the self who refuses to know, departs from the scene, leaving the body behind. The emphasis is on the sheer enormity, the unbearable nature of the abusive event (Radstone, 2000a, p. 89). Dissociation in this context is therefore seen as being used when repression cannot do the trick (Mollon, 1998b, p. 127; Southgate, 2002, p. 95). I will now focus on a particular representation of dissociation, which I will refer to as the frozen baby discourse. Here, in a number of examples of this discursive formation, is where we can see several mentions of Winnicotts true self. This representation refers to the dissociated child within who knows what is going on and carries this knowledge hidden away in cold storage all the way into adulthood, ready to be recovered at the right moment. The frozen baby/child-within is a well-known discourse, which is present explicitly or implicitly wherever the dissociation concept is used in the psychoanalytically-informed trauma paradigm literature.6 This frozen baby is envisaged as the keeper of a memory something almost material, a thing locked away. It is therefore a secret to be hidden from all eyes, but at the same time, to be preserved at all costs. This locked knowledge is then forgotten, dissociated. In this representation of dissociation the metaphors of coldness, freezing as well as melting and thawing are often to be found, leading to an association with the process of putting something in the deep-freeze: the underlying idea being that the locked away frozen baby is unaffected by the passage of time. There is therefore an interesting conceptualization of time in this construction.

394

M. Papadima

What follows is an illustration, extracted from a piece of writing by a psychoanalyst who discusses dissociative identity disorder through a clinical example. This extract gives a good, strong avour of what is at stake in the frozen baby discourse: Instantly, to aid the woman, out of cold storage came the brave 6-year-old friend. Frozen in a terrible state of now-ness that had not changed for over 30 years she emerged . . . Some states were truly frozen not just in time but in their emotional states, pointing to disorientated disorganized attachments and even earlier infantile trauma . . . After two years of treatment they began to thaw, began to grow and discard their old strictures. Some of the frozen friends could then melt into their host bringing their strength, fragments of memory and courage back to the core personality (Sinason, 2002, p. 3; italics mine). All the aspects of the frozen baby discourse are evident here, as are the terms of the Janet-inspired rst debate on dissociation in the context of which this piece plainly belongs. The brave frozen baby (here actually a 6year-old child) emerges from cold storage to aid the now adult woman. Gradually, with the help of the analyst, the brave 6-year old and the woman become one, making use at last of the frozen babys knowledge, its fragments of memory and its strength and courage. The words strength and courage give pause for thought. Who is the subject who is referred to here? Who is courageous and strong? The 6-year old friend, who comes to the rescue of the older woman, is referred to as a cohesive, hidden self. A true self understood in a completely nonWinnicottian way. This baby is envisaged as an object, a piece of knowledge that has been put away, and, at the same time, paradoxically, as a subject, a strong and courageous parallel self. The contradiction is self-evident: who put this frozen baby into cold storage? Did it perhaps go into cold storage on its own accord? Did it then stay there voluntarily and how did it know to come out when she/he was needed? These questions may sound nonsensical, but Sinasons passage is written in all seriousness. The implications of her case-example deserve to be looked at because, at its core, the frozen baby discourse refers to subjectivity itself: Who is the subject who experiences the abuse and then gets frozen and hidden away? What kind of subjectivity are we talking about here? In order to better understand the frozen baby discourse and the dead ends to which it leads, I will now discuss the uses of Winnicotts terminology in various trauma paradigm papers. Psychoanalytic or non-psychoanalytic Winnicott? When looking at the term true self and the way it is used in trauma paradigm writings, we nd what Lacan refers to as a wearing down of the

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Dissociation and the true self

395

angles . . . a softening, reductive smoothing out (Lacan, 1981, p. 237) of what is essential about Winnicott. For example, Sue Richardson, in an attachment-theory analysis of work with dissociative conditions, refers to Winnicotts true self in cold storage (Richardson, 2002, p. 150). When closely examining the reference she provides, we nd a mention to Winnicotts (1960) collection of essays The maturational processes and the facilitating environment in its entirety. We also nd that nowhere in any part of that book does Winnicott refer to the true self as being in cold storage. This is Richardsons addition, and it is quite telling. This is an illustration of the frozen baby discourse grafted onto Winnicotts text. Richardsons addition of cold storage deserves thinking about, especially when linking it to her subsequent conceptualization of this frozen baby: It is the little creature within the traumatised adult who is in need of containing contact. Where that is successfully accomplished, there is a process of emergence (Richardson, 2002, p. 149). What these phrases imply is, again, that there is a subject who has experienced trauma, has gone into hiding, and will emerge intact when successful containing is accomplished. Regarding the reference to cold storage, let us look more closely at its metaphorical use and the implications of this use. When a food item is placed in cold storage, we hope, as much as possible, to insulate it from the environment (both space air, bacteria, etc. and time). When retrieved, we hope to nd it as good as new. Yet in practice this is not possible. First, because when a food item is left too long in cold storage, its quality will undoubtedly decrease: it will not actually be as good as new; rather, it will have a vague but distinct oldness to it. Second, because the freezer is in itself a specic kind of environment, albeit one that slows the decomposing process; it is not a non-environment. The passing of time does then inuence, even when frozen, the condition of the food item, since nothing, in the end, can be entirely insulated. Richardsons true self in cold storage is an illusory idea, since as the Freudian ideas about time and memory show (and as the example of the freezer also shows!) there is no untouched memory: memory, including traumatic memory, is reworked constantly through the process of nachtraeglichkeit: trauma does not consist only or essentially in its original occurrence (the earliest scene), but in its retrospective recollection (the latest scene) (Green, 2005, p. 175). The idea of a traumatic memory or even more, a whole traumatized inner self in cold storage unaffected by the constant unconscious reworking over time is simply untenable in a Freudian framework. Similar examples of the true, frozen self in hiding abound in the trauma paradigm literature. What is interesting is the frequent use, in passing, of the Winnicottian true self described as hidden or temporarily suppressed. A good illustration comes, again, from Phil Mollons work. In a chapter entitled Dissociation between true and false self,

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

396

M. Papadima

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Mollon begins by boldly stating that Winnicotts (1960) description of a division between true and false self is not an account of repression but of dissociation (Mollon, 1996, p. 12). After giving a short account of Winnicotts theory, focusing on the importance of the mothers decient adaptation to the child, he uses the phrase the true self is held in abeyance. This phrase clearly points to something with a prior existence, which is temporarily inactive or suppressed. Mollon goes on to give examples, through clinical material, of severe traumatic experiences, usually the result of repeated painful interactions with a primary caregiver (Mollon, 1996, p. 13), which create despair about ever being known and understood (Mellon, 1996). Again, what is evoked here, and unequivocally referred to, is a true self in hiding because of too much pain (similar examples can be found in De Zulueta, 1993, pp. 106, 126; Messler Davies & Frawley, 1994, p. 5; Mollon, 1998a, p. 7, Whewell, 2002, p. 171). Hiding is the operative term here. In their description of Winnicotts true self theory, Peter Fonagy and his co-authors make the following statement: Winnicott described the powerful desire to develop a sense of self and conversely how powerfully it may be hidden or falsied (Fonagy et al., 1995, p. 520). It is interesting that, however subtle and wellarticulated their description of the true-self theory, in the end one is left to question whether in these authors account the true self as such has ever existed or not. The phrase the false self provides a screen behind which the true self can secretly search for actualization (Fonagy et al., 1995, p. 522) further clouds the issue, since a hidden subjectivity is implied, which is actively, if unconsciously, involved in a process of searching for actualization. What is accomplished by such references? Mainly, the creation of a non-psychoanalytic Winnicott who squarely belongs to the tradition that follows Janetian dissociation and very early Freudian conceptualizations. Yet, since Winnicott is known as an important psychoanalyst, what is also paradoxically accomplished is the maintenance of a link to the psychoanalytic tradition. Winnicotts absent baby Apart from the dead-ends that the metaphor of the deep-freeze lead to, the representation of true self in hiding misreads Winnicott in an even more fundamental way. Starting from his 1960 paper on the true/false self, and reading it side by side with Fear of breakdown (Winnicott, 1974) and Ego integration in child development (Winnicott, 1962), it becomes apparent that Winnicott is interested in very early psychic processes that have to do with the process of self (or ego) creation. He is painting a picture of the acquisition of self, taking close notice of the facilitating environment and the prerequisites for this developmental process to occur as smoothly as possible. The trauma that Winnicott refers to cannot be understood as a

Dissociation and the true self

397

concrete, observable instance of abuse, not because something like that would not be possible in early stages of life, but because what is traumatic for a very young infant cannot be measured from the point of view of an adult. It should be noted that this conceptualization of discernible trauma is simply not Winnicotts area of interest in these papers. Furthermore, in the 1962 paper Winnicott clearly states that the traumatic events he refers to have to do with the early stage before the baby has separated off the not-me from the me (Winnicott, 1962, p. 58). He uses the term unthinkable anxiety to show that the aforementioned traumatic event is not thought, not represented by the baby, but in a way kickstarts prematurely an initial awareness, an ego root which is a long distance in time prior to the establishment of anything that could usefully be called the self (Winnicott, 1974, p. 107). This means that the traumatic event has not been experienced in any way. There is literally no one there to experience it, since there is no ego separate from the environment. What the baby does experience is a primitive, bodily agony (and its particular variation of the fear of falling for ever) that leads to self-holding in the absence of adequate environmental holding: this is done through the establishment of the false self-organization, which can be understood as a kind of protective shell. It has to be stressed though that the false self is not protecting and hiding an already established true self, since the true self is merely a potentiality and has not had the chance to exist. What the false self protects and reveals is the fact of the true selfs absence from the scene (Winnicott, 1962, p. 59). It is the unattributable dread which keeps the adult person looking for this detail in the future (Winnicott, 1974, p. 104); the constant searching for the reality of some trauma or catastrophe that will help to place and experience the unlived and unrepresented breakdown or trauma; these are the important elements of Winnicotts account. In other words, the potential true self has not started to exist (Winnicott, 1960, p. 142) since it has been subsumed by the false self defence brought about abruptly as a result of the trauma. In Winnicotts conceptualization of trauma, then, the important point is the non-existence of the true self and its potential, which can perhaps later be created (not re-created, but created) through the play of the analytic situation. In this way, at long last the traumatic event may be experienced, represented, and brought under the selfs control. In this description, Winnicott is strikingly near to Freuds account in Analysis terminable and interminable: Each ego is endowed from the rst with individual dispositions and trends, though it is true that we cannot specify their nature or what determines them . . . When we speak of an archaic heritage we are usually thinking only of the id and we seem to assume that at the beginning of the individuals life no ego is as yet in existence. But we shall not overlook the

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

398

M. Papadima

fact that id and ego are originally one; nor does it imply any mystical overvaluation of heredity if we think it credible that, even before the ego has come into existence, the lines of development, trends and reactions which it will later exhibit are already laid down for it (Freud, 1937, p. 240, italics mine). In Freud, the id and ego are originally one; in Winnicott, ego and environment are originally one. The main point, in both authors, is that there is no separate ego (self) to speak of at the beginning of life. Rather, there is a genetically biased set of dispositions, a mere potentiality (Bollas, 1991, p. 9). Winnicott uses the imagery of a true self to talk about a potentiality of spontaneous impulse (Winnicott, 1960, p. 145), which is a process of self-creation, of ego integration. When the trauma-paradigm authors therefore refer to Winnicotts true self, they are misreading a central idea, which is close to Freuds 1938 understanding of the split self. There is no true self in hiding. There is no frozen baby who will come to the rescue and bring a longed-for wholeness to the adult person. The only sign of the true selfs phantasmatic existence is the fear of breakdown, which brings to mind the unlived early traumatic event an event which cannot be relived but can be lived, possibly, for the rst time in the analytic context. Consequently, when talking about Winnicotts true self in the context of traumatic child abuse, any notion of dissociation has to be excluded, since dissociation presupposes an already formed, unitary, self/ego which, following a trauma, gets split in two (or more) distinct fragments. Even if we are to imagine a case of possible child abuse occurring in these extremely early days of the infants life, we could still not talk about dissociation or a frozen baby in hiding: we would need to understand what has occurred in the context of the dread that refers to an event that has not been experienced but can only be deduced from its consequences. In conclusion, Winnicotts true self, in striking contrast to the illusory frozen baby that can come out of hiding at the right moment, can only be known by the consequences of its non-existence. It is a fundamental absence that Winnicott is talking about, an absence that can never be lled, and this is why his writing is in stark opposition to the trauma-paradigm authors that refer to his work. In this way, Winnicotts work belongs to the tradition of the second debate on dissociation, outlined above, placing him within the Freudian line of thought concerning splitting, subjectivity and the self. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Corinne Squire, Susannah Radstone, Alexandros Ilias, Nick Midgley, Anouk Riviere and Ruth McCall for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. I would also like to thank the two

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Dissociation and the true self

399

anonymous reviewers of Psychodynamic Practice for their very useful comments. Notes 1 I use the term paradigm because it is favoured by many of these writers. It is indeed striking how often the shift to a more trauma-based model in psychoanalysis is enthusiastically referred to as a paradigm shift (see for example Waugaman, 2000) emphasizing the break with the old and the embracing of the new. 2 Fonagy & Target (1995, p. 162) explain that dissociation is not always linked to trauma; that is, it is conceivable that there are certain people who show a lack of capacity to unify content-specic elementary structures into a singular consciousness (Fonagy & Target, 1995, p. 162). However, for the purposes of this paper, dissociation will be understood as resulting from trauma, since this is by far its most common representation in the relevant literature. 3 For more information on this non-psychoanalytic understanding of dissociation and its link to Janets work, see among others Hacking (1995); Leys (2000); and LeBlanc (2001). 4 Following the Althusserian understanding of science, Freud created a new science, the object of which a revolutionary discovery on Freuds part is the unconscious (Althusser, 1964). 5 In this paper, I will not look at the Kleinian understanding of trauma and dissociation, since this tradition cannot be seen as belonging to the trauma paradigm, although there are perhaps certain similarities. It is however outside the scope of this paper to explore these possible similarities in detail. Sufce to say here that in Kleinian theory dissociation is not utilized, but is mostly examined in the context of wider discussion around splitting as a primitive psychic mechanism, although the theoretical framework is different from that of attachment theory and relational psychoanalysis. 6 It is also a well-known discourse in pop psychology/self-help texts, which focus on the child within and the healing work that needs to be done in order to gain access to this inner child or, indeed, in order to save it. References

Alexander, P. C. (1992). Application of attachment theory to the study of sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 185 195. Althusser, L. (1964). Freud and Lacan. In O. Corpet, & F. Matheron (Eds.), Freud and Lacan. New York: Columbia University Press. Arnold, K. (2005). Intersubjectivity, multiplicity and the dynamic unconscious. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 41, 519 533.

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

400

M. Papadima

Balint, M. (1979). The basic fault: Therapeutic aspects of regression. London & New York: Tavistock. Bollas, C. (1991). Forces of destiny: Psychoanalysis and human idiom. London: Free Association Books. Brenner, I. (1999). Deconstructing DID. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 53, 344 360. Brenner, I. (2001). Dissociation of trauma: Theory, phenomenology and technique. Madison, CT: International Universities Press. Bromberg, P. M. (1996a). Hysteria, dissociation and cure: Emmy von N. revisited. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 6, 55 71. Bromberg, P. M. (1996b). Standing in the spaces: The multiplicity of self and the psychoanalytic relationship. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 32, 509 535. Bromberg, P. M. (1998). Standing in the spaces: Essays on clinical process, trauma and dissociation. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press. Burton, N., & Lane, R. C. (2001). The relational treatment of dissociative identity disorder. Critical Psychology Review, 21, 301 320. Carlson, E. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (1995). Contribution of attachment theory to developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 1, Theory and methods. New York: John Wiley. Chefetz, R. A., & Bromberg, P. M. (2004). Talking with me and not-me: A dialogue. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 40, 409 464. De Zulueta, F. (1993). The traumatic roots of destructiveness: From pain to violence. London: Whurr. Diamond, D. (2004). Attachment disorganization: The reunion of attachment theory and psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 21, 276 299. Eagle, M. (2000). The developmental perspectives of attachment and psychoanalytic theory. In S. Goldberg, R. Muir, & J. Kerr (Eds.), Attachment theory: Social, developmental and clinical perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ & London: The Analytic Press. Ellenberger, H. (1970). The discovery of the unconscious: The history and evolution of dynamic psychiatry. London: Allen Lane, The Penguin Press. Evans, D. (2001). An introductory dictionary to Lacanian psychoanalysis. Hove & New York: Brunner-Routledge. Fonagy, P. (2001). Attachment theory and psychoanalysis. London & New York: Karnac. Fonagy, P. (2002). Multiple voices versus meta-cognition: An attachment theory perspective. In V. Sinason (Ed.), Attachment, trauma and multiplicity: Working with dissociative identity disorder. Hove & New York: Brunner-Routledge. Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1995). Dissociation and trauma. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 8, 161 166. Fonagy, P., Target, M., Steele, M., & Gerber, A. (1995). Psychoanalytic perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 1, Theory and methods. New York: John Wiley. Freud, S. (1918). From the history of an infantile neurosis. SE, 17. London: Hogarth Press. Freud, S. (1923). The infantile genital organisation. SE, 19. London: Hogarth Press. Freud, S. (1925). Psychical consequences of an anatomical distinction between the sexes. SE, 19. London: Hogarth Press. Freud, S. (1927). Fetishism. SE, 21. London: Hogarth Press. Freud, S. (1937). Analysis terminable and interminable. SE, 23. London: Hogarth Press. Freud S. (1938a). An outline of psychoanalysis. SE, 23. London: Hogarth Press. Freud, S. (1938b). Splitting of the ego in the process of defence. SE, 23. London: Hogarth Press. Freud, S., & Breuer, J. (1895). Studies on hysteria. SE, 2. London: Hogarth Press. Green, A. (2005). Key ideas for a contemporary psychoanalysis: Misrecognition and recognition of the unconscious. London & New York: Routledge.

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

Dissociation and the true self

401

Hacking, I. (1995). Rewriting the soul: Multiple personality and the sciences of memory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Hinshelwood, R. D. (1991). A dictionary of Kleinian thought. London: Free Association Books. Hinshelwood, R. D. (2002). The dividual person: On identity and identications. In V. Sinason (Ed.), Attachment, trauma and multiplicity: Working with dissociative identity disorder. Hove & New York: Brunner-Routledge. Janet, P. (1889). Lautomatisme psychologique. Paris: Alcan. Lacan, J. (1981). An address: Freud in the century. The psychoses: The seminar of Jacques Lacan, book III 1955 1956. New York & London: Routledge. Laplanche, J., & Pontalis, J. B. (1986). Lexilogio tis psychanalysis (Vocabulaire de la psychanalyse). Athens: Kedros. Laub, D. (2003). Trauma, early development and psychopathology. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 51, 669 674. Leblanc, A. (2001). The origins of the concept of dissociation: Paul Janet, his nephew Pierre and the problem of post-hypnotic suggestion. History of Science, xxxix, 57 69. Leys, R. (2000). Trauma: A genealogy. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press. Liotti, G. (1992). Disorganized/disoriented attachment in the etiology of the dissociative disorders. Dissociation, 5, 196 204. Messler Davies, J. (1996). Linking the pre-analytic with the postclassical: Integration, dissociation, and the multiplicity of unconscious processes. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 32, 553 576. Messler Davies, J., & Frawley, M. G. (1994). Treating the adult survivor of childhood sexual abuse: A psychoanalytic perspective. New York: Basic Books. Midgley, N. (2002). Child dissociation and its roots in adulthood. In V. Sinason (Ed.), Attachment, trauma and multiplicity: Working with dissociative identity disorder. Hove & New York: Brunner-Routledge. Mills, J. (2005). A critique of relational psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 22, 155 188. Mitchell, S. A., & Aron, L. (Eds.) (1999). Relational psychoanalysis: The emergence of a tradition. Hillsdale, NJ & London: The Analytic Press. Mollon, P. (1996). Multiple selves, multiple voices: Working with trauma, violation and dissociation. London: Wiley. Mollon, P. (1998a). Remembering trauma: A psychotherapists guide to memory and illusion. London & Philadelphia: Whurr Publishers. Mollon, P. (1998b). Terror in the consulting-room Memory, trauma and dissociation. In V. Sinason (Ed.), Memory in dispute. London: Karnac. Radstone, S. (2000a). Screening trauma: Forrest Gump, lm and memory. In S. Radstone (Ed.), Memory and methodology. Oxford & New York: Berg. Radstone, S.(2000b). Working with memory: An introduction. In S. Radstone (Ed.), Memory and methodology. Oxford & New York: Berg. Richards, A. (Ed.) (1974). Indexes and bibliographies, SE, 24. London: Hogarth Press. Richardson, S. (2002). Will you sit by her side? An attachment-based approach to work with dissociative disorders. In V. Sinason (Ed.), Attachment, trauma and multiplicity: Working with dissociative identity disorder. Hove & New York: Brunner-Routledge. Sinason, V. (2002). Introduction. In V. Sinason (Ed.), Attachment, trauma and multiplicity: Working with dissociative identity disorder. Hove & New York: Brunner-Routledge. Slavin, M. O. (1996). Is one self enough? Multiplicity in self-organization and the capacity to negotiate relational conict. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 32, 615 625. Southgate, J. (2002). A theoretical framework for understanding multiplicity and dissociation. In V. Sinason (Ed.), Attachment, trauma and multiplicity: Working with dissociative identity disorder. Hove & New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

402

M. Papadima

Strachey, J. (1964). Editors note: Splitting of the ego in the process of defence. SE, 23. London: Hogarth Press. Waugaman, R. M. (2000). Multiple personality disorder and one analysts paradigm shift. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 20, 207 226. Whewell, P. (2002). Profound desolation: The working alliance with dissociative patients in an NHS setting. In Sinason, V. (Ed.), Attachment, trauma and multiplicity: Working with dissociative identity disorder. Hove & New York: Brunner-Routledge. Winnicott, D. W. (1960). Ego distortion in terms of true and false self. The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. London: Karnac. Winnicott, D. W. (1962). Ego integration in child developmentThe maturational processes and the facilitating environment. London & New York: Karnac. Winnicott, D. W. (1974). Fear of breakdown. International Review of Psychoanalysis, 1, 103 107.

Downloaded By: [HINARI Consortium (T&F)] At: 12:29 16 April 2010

You might also like

- RighteousnessDocument24 pagesRighteousnessAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Personality Traits of AlcoholicsDocument1 pagePersonality Traits of AlcoholicsAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Baptism in The Holy Spirit PDFDocument9 pagesBaptism in The Holy Spirit PDFAlbert Muya Muraya100% (1)

- Four Steps Out of Tribulation PDFDocument0 pagesFour Steps Out of Tribulation PDFAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Praising GodDocument4 pagesPraising GodAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

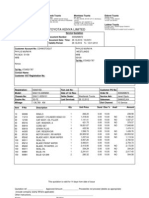

- KAN 519 D - Westlands Toyota QuotationDocument2 pagesKAN 519 D - Westlands Toyota QuotationAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of GivingDocument3 pagesDoctrine of GivingAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- A Person-Centered Approach To The Treatment of BPDDocument29 pagesA Person-Centered Approach To The Treatment of BPDAlbert Muya Muraya100% (1)

- Finding The Self in MindDocument15 pagesFinding The Self in MindAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Carl Rogers - Theory of PersonalityDocument2 pagesCarl Rogers - Theory of PersonalityAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- SFP EasyIntroToEganDocument5 pagesSFP EasyIntroToEganAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Transtheoretical Theory Model - Prochaska - WikipediaDocument10 pagesTranstheoretical Theory Model - Prochaska - WikipediaAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Kingdom Academy: Submitted Under The New Creation Realities Course in Partial Fulfilment of TheDocument3 pagesKingdom Academy: Submitted Under The New Creation Realities Course in Partial Fulfilment of TheAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Godhead Assignment IIDocument3 pagesGodhead Assignment IIAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Christian ApologeticsDocument5 pagesChristian ApologeticsAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- New Creation RealitiesDocument3 pagesNew Creation RealitiesAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- From Freuds Consulting Room PDFDocument346 pagesFrom Freuds Consulting Room PDFismailtaaa100% (1)

- PSY 312-History of Modern Psychology-Imran RashidDocument4 pagesPSY 312-History of Modern Psychology-Imran RashidAmmar HassanNo ratings yet

- Dissociation, The True Self and The Notion of The Frozen BabyDocument19 pagesDissociation, The True Self and The Notion of The Frozen BabyAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- Books Reconsidered: The Unconscious Before Freud: Lancelot Law WhyteDocument3 pagesBooks Reconsidered: The Unconscious Before Freud: Lancelot Law WhyteMateusz CzerniawskiNo ratings yet

- Great Books Recomendations - Jordan PetersonDocument4 pagesGreat Books Recomendations - Jordan PetersonA. AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Henri F. Ellenberger EthnopsychiatryDocument381 pagesHenri F. Ellenberger EthnopsychiatryHeráclito Aragão Pinheiro100% (1)

- Esca Bios IsDocument15 pagesEsca Bios Isjeisson leonNo ratings yet

- Ellenberger PDFDocument974 pagesEllenberger PDFCyberabad2598% (50)

- Jordan Peterson Book RecommendationsDocument6 pagesJordan Peterson Book RecommendationsJerome RafaelNo ratings yet

- Jay Sherry - Carl Jung Avant-Garde ConservativeDocument282 pagesJay Sherry - Carl Jung Avant-Garde ConservativeRodrigo Caron100% (1)

- Peterson CourseDocument3 pagesPeterson CourseTeodora IoanaNo ratings yet

- The Syndetic Paradigm: Robert AzizDocument334 pagesThe Syndetic Paradigm: Robert AzizBrian S. Danzyger100% (2)