Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History and The Canon: The Case of Doctor Faustus

Uploaded by

samcoltrinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History and The Canon: The Case of Doctor Faustus

Uploaded by

samcoltrinCopyright:

Available Formats

MICHAEL H.

KEEFER

History and the Canon: The Case of

Doctor Faustus

The relationship between the two key words of my title is a curiously intricate one. Since the notion of canonicity implies a controlled transmis sion of the past into the future, to talk about literary canons is also, unavoidably, to invoke one or another view of history. Yet, paradoxically, some of the recently and currently most inuential critical positions have encouraged understandings of canonicity that are thoroughly antihistorical. I shall be concerned in the rst part of this essay with some of the implications of this paradox. In the second part, turning to Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, a play that is by common consent of some importance in our literary canon, I will consider certain practical consequences, both textual and interpretive, of attempts to lift the canon out of history. Another less stolid title, that of a recent academic conference, may serve to introduce the issues I wish to discuss. 'Beyond the Canon: Literary Innovation and Integration' - these words, from one point of view, are no more than an elliptical summary of the inescapable process of canon revision. Any new text is 'beyond the canon' in the banal sense of being not yet canonical - and sometimes also in the more interesting sense of being genuinely innovative, of embodying moves that extend beyond the limits implied by the current literary canon. Critical commen tary, where it is not simply dismissive, serves to integrate the new text into the canon by discovering some degree of 'conformity between the old and the new/ which also implies making adjustments to the 'ideal order' formed by the 'existing monuments' of literature.1 This is a familiar perspective, as the tags from T.S. Eliofs Tradition and the Individual Talenf will already have signalled. And it is one that within certain limits can accommodate historically oriented canon revisions as well: witness Eliofs revisionary insistence that 'the main current... does not at all ow invariably through the most distinguished reputations.'1 But perhaps 'Beyond the Canon' is meant to evoke something a little more exciting. Taken in another sense, the words suggest, indeed invite, a kind of deliberate transgression. Since in other contexts a prepositional phrase of this kind might as easily be hortatory as descriptive, can one be blind in this case to its hidden persuasive force? 'Down to the river! into the street!' cried Allen Ginsberg in the second part of Howl.3 Why not then 'Beyond the Canon!'? Yet as we surge forward, arm in arm, two doubts may assail us.

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO QUARTERLY, VOLUME 56, NUMBER 4, SUMMER 1987

You might also like

- Accute NL Dec 1992Document16 pagesAccute NL Dec 1992samcoltrin100% (1)

- Verbal Magic and The Problem of The A and B Texts of Doctor FaustusDocument24 pagesVerbal Magic and The Problem of The A and B Texts of Doctor FaustussamcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Doctor Faustus: A 1604-Version EditionDocument90 pagesIntroduction To Doctor Faustus: A 1604-Version EditionMichael KeeferNo ratings yet

- Introduction To "The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus: A Critical Edition of The 1604 Version"Document163 pagesIntroduction To "The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus: A Critical Edition of The 1604 Version"samcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Accute NL Mar 1993Document24 pagesAccute NL Mar 1993samcoltrin100% (1)

- Accute NL Sept 1992Document16 pagesAccute NL Sept 1992samcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Accute NL Dec 1993Document24 pagesAccute NL Dec 1993samcoltrinNo ratings yet

- ACCUTE NL Supplement - March 1992Document19 pagesACCUTE NL Supplement - March 1992samcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Accute NL June 1993Document20 pagesAccute NL June 1993samcoltrin100% (1)

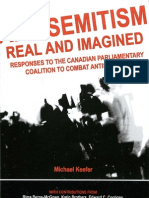

- Antisemitism: Real and ImaginedDocument298 pagesAntisemitism: Real and ImaginedsamcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Accute NL June 1994Document36 pagesAccute NL June 1994samcoltrin100% (1)

- Accute NL March 1994Document20 pagesAccute NL March 1994samcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Accute NL Sept 1993Document16 pagesAccute NL Sept 1993samcoltrin100% (1)

- Lunar Perspectives: Field Notes From The Culture WarsDocument252 pagesLunar Perspectives: Field Notes From The Culture Warssamcoltrin100% (1)

- Fraud and Scandal in Haiti's Presidential Election: Préval's Victory and UN's DisgraceDocument29 pagesFraud and Scandal in Haiti's Presidential Election: Préval's Victory and UN's DisgracesamcoltrinNo ratings yet

- War Against Iraq-ResourcesDocument99 pagesWar Against Iraq-Resourcessamcoltrin100% (1)

- Keefer Declaring ExceptionDocument19 pagesKeefer Declaring ExceptionsamcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Alison - Race Gender and ColonialismDocument367 pagesAlison - Race Gender and ColonialismsamcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Keefer Politics of SolidarityDocument18 pagesKeefer Politics of SolidaritysamcoltrinNo ratings yet

- The Six Nations Land Reclamation: ( ( (Roundtable) ) )Document33 pagesThe Six Nations Land Reclamation: ( ( (Roundtable) ) )samcoltrinNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- N List Aug 2012Document5 pagesN List Aug 2012rajeevdudiNo ratings yet

- As 4055-2006 - Amdt 1-2008 Wind Loads For HousingDocument8 pagesAs 4055-2006 - Amdt 1-2008 Wind Loads For HousingBrad La PortaNo ratings yet

- Crafts From India, Shilparamam, Crafts Village of Hyderabad, Shilparamam Crafts Village, IndiaDocument2 pagesCrafts From India, Shilparamam, Crafts Village of Hyderabad, Shilparamam Crafts Village, IndiavandanaNo ratings yet

- Gluck On The Reform of OperaDocument1 pageGluck On The Reform of Operahebrew4100% (1)

- St. John Climacus - The Ladder of Divine AscentDocument159 pagesSt. John Climacus - The Ladder of Divine AscentEusebios Christofi100% (11)

- Ballroom Dance NotesDocument12 pagesBallroom Dance Notesmaelin dagohoyNo ratings yet

- Test de Evaluare Initiala A12aDocument2 pagesTest de Evaluare Initiala A12aRamona AndaNo ratings yet

- MonacoDocument7 pagesMonacoAnonymous 6WUNc97No ratings yet

- Mixed Twnses English CourseDocument2 pagesMixed Twnses English CourseMorrieNo ratings yet

- Timeline Tender ADocument4 pagesTimeline Tender Azulkifli mohd zainNo ratings yet

- Class 8 - TopicsDocument33 pagesClass 8 - TopicsAmit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Obaidani ProfileDocument16 pagesObaidani Profilekumar4141No ratings yet

- Panitia Bahasa Inggeris: Program Peningkatan Prestasi AkademikDocument53 pagesPanitia Bahasa Inggeris: Program Peningkatan Prestasi AkademikPriya MokanaNo ratings yet

- ) Caterina de Nicola Selected Works (Document19 pages) Caterina de Nicola Selected Works (Catecola DenirinaNo ratings yet

- Pedestrian BridgesDocument16 pagesPedestrian Bridgesdongheep811No ratings yet

- Already But Not Yet: David Feddes!Document168 pagesAlready But Not Yet: David Feddes!BenjaminFigueroa100% (1)

- Stair Details by 0631 - DAGANTADocument1 pageStair Details by 0631 - DAGANTAJay Carlo Daganta100% (1)

- Mikroskop GeneralnoDocument24 pagesMikroskop GeneralnoikonopisNo ratings yet

- Theravada Buddhism ExplainedDocument18 pagesTheravada Buddhism ExplainedMaRvz Nonat Montelibano100% (1)

- Obituary Death Revhi PDFDocument6 pagesObituary Death Revhi PDFYildirimFrisk93No ratings yet

- Poems of The Islamic Movement of UzbekistanDocument13 pagesPoems of The Islamic Movement of UzbekistanLeo EisenlohrNo ratings yet

- The Aesthetic Appreciator in Sanskrit PoeticsDocument9 pagesThe Aesthetic Appreciator in Sanskrit PoeticsSandraniNo ratings yet

- Listening Exercises 1 - MelisaDocument5 pagesListening Exercises 1 - Melisamelisa collinsNo ratings yet

- 7 Bible Verses About the Power of Your ThoughtsDocument9 pages7 Bible Verses About the Power of Your ThoughtswondimuNo ratings yet

- Mintmade Fashion: Fresh Designs From Bygone ErasDocument15 pagesMintmade Fashion: Fresh Designs From Bygone ErasShivani ShivaprasadNo ratings yet

- Maki Part1Document17 pagesMaki Part1Slobodan VelevskiNo ratings yet

- Septic Tank and Soak Away PitDocument1 pageSeptic Tank and Soak Away Pitcprein9360% (5)

- Eucharist PDFDocument2 pagesEucharist PDFMarkNo ratings yet

- TOPAZ GLOSS EMULSIONDocument2 pagesTOPAZ GLOSS EMULSIONsyammcNo ratings yet

- m006 Modal Test Junio 17Document2 pagesm006 Modal Test Junio 17Alex Saca MoraNo ratings yet