Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Tao of The Dow

Uploaded by

TawanannaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Tao of The Dow

Uploaded by

TawanannaCopyright:

Available Formats

1

THE TAO OF THE DOW A Philosophy of Financial Securities Investing

By R.S. Heyer

1993

PREFACE

This little book distills the results of 35 years of investment experience, crystallized and conveniently expressed in terms of principles expressed in the Tao, but reached independently. The pun in the title is my own proclivity, but the idea of combining these two elements was inspired in part by such examples as the Tao of Physics, the Tao of Leadership, and the less serious Tao of Programming. The reader need not conscientiously peruse every line of this book to make use of it, although every author hopes that every reader will benefit from every word written. The plan of the work consists of four principal parts, each of which provides its own value and can be read separately. The first part presents the fundamental principles of the Tao, as I construe it. My approach differs from that of others, but that is not unusual or surprising. This part contains chapters I-III. Those mainly interested in the Tao, in an analytic way, but not in investment, might read only this. The second part details the application of these general principles to the particulars of investment problems. This is the longest part, containing chapter IV, parts A-D, and chapter VII. Those interested only in the investment practicalities might concentrate on this part. The third part contains a lighter, more sloganeering, less analytic approach to investment philosophy. It consists of appendices I and II. Appendix I relates to investment ideas suggested by each verse or section of the Tao, arranged in the poetic order in which the Tao itself is known rather than any analytic order. Although this is a verse-by-verse approach, it is not a translation by any means, but a sort of correlation, numbered to correspond to the verses of the Tao. Appendix II is a set of modern aphorisms (some old, some new, some revised) which are or might appropriately be applied to investment. Some readers may prefer this part to any of the others. It was the most fun to put together. The fourth part consists of the remaining appendices, which provide additional information which may be useful to the investor, especially a new one, for reference only. Appendix III contains acronyms and other odd abbreviations which help a new investor in reading or listening to the financial news media, and Appendix IV lists formulas used by fundamental analysts, as suggested by Graham and Dodd, and their successors, Cottle, Murray, and Block. It is hoped that the reader will enjoy and find useful this little book. It is of course too short to be complete in any of its aspects, certainly not in the summary of financially pertinent reality. For greater detail the reader may consult other sources, a few of which are suggested in the bibliography included after Appendix IV. Suggestions for corrections, clarifications, and additions are welcome. Taoism refers to the doctrines expressed in a concise ancient book, the name of which is usually spelled Tao Te Ching in English, following the Wade-Giles spelling system for Chinese (Dao De Jing in Pinyin). It is pronounced dow duh jing referring to the concept of the Tao (pronounced Dow), the Way of nature and of sensible human behavior. Hence The Tao of the Dow is a play on the identical sound of the two words, Tao (or Dao) and Dow. Some observers regard the Tao as emphasizing mere passivity,

3 but it was intended as advice to government in a tyrannical time; therefore, a more plausible and useful view is that the Tao is a guide to action, allowing for more patience, more forbearance, more reason and self-control, more liberalism of spirit than the actual tyrants of the time displayed.

THE TAO OF THE DOW Table of Contents

Preface Table of Contents I. II. III. IV. Introduction Harmonious Balance Cosmic Harmony in General Financial Securities Investing Defined A. Investing B. Financial Securities Harmonious Balance in Investing A. Psycho-Strategic Balance (Appropriate Goals) B. Emotional Balance (Reasoned Action) C. Market and Selection Balance (Independence, Avoidance of Extremes) D. Chronological Transactions Balance (Averaging) E. Portfolio-Holdings Balance 1. Asset Allocation 2. Diversification 3. Geographic Balance 4. Risk Balance F. Balance in Approach (Adaptability, Flexibility) Cosmic Harmony in Investing: A. Initial Comments B. Background Environment 1. Economic Environment a. Nature of Economy b. Financial Securities c. Classic Economic Laws d. Effective Demand e. Organizational Flexibility and Social Inclusivity f. Economic Cycles g. Interest Rates h. Geographical Scope of Economic Environment 2. Politics 3. Resources 4. Trading System C. Fundamental Analysis 1. Objectives and General Principles 2 4 6 9 12 14 14 14 17 17 17 18 18 19 20 20 20 20 20 22 24 24 24 25 25 29 30 32 34 36 36 37 39 40 40

V.

VI.

6 Valuing Debt Securities Valuing Stocks Compound Interest Rule of 72 Reading an Annual Report Primary Factors Accounting Concepts a. Earnings Report (profit) b. Balance Sheet (equity, book value) c. Cash Flow 9. Ratios a. Measures of Progress b. Measures of Value c. Measures of Safety d. Measures of Profitability and Stability D. Technical Analysis 1. Trends 2. Dow Theory 3. Averages and Indices 4. Patterns 5. Support and Resistance 6. Volume 7. Sentiment 8. Seasonality Conclusion 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 41 41 42 43 43 44 46 46 47 47 47 47 48 49 49 50 50 51 51 52 52 53 53 54 55 56 64 67 74 81

VII.

Appendix I. Interpretation and Application of Each Verse Appendix II. Aphorisms Appendix III. Acronyms Appendix IV. Formulas Bibliography

I.

Introduction

Principles of good sense and sound behavior long endure and widely apply. A truly sound philosophy can provide valuable guidance in a surprisingly wide variety of times and circumstances. Much of life turns out to consist of finding ways in which lessons learned in one context often apply to other contexts as well. For example, 25 centuries ago in China a man known simply as the Old Master wrote a poem to guide his people and especially the rulers through troubled times. The Chinese call that poem the Tao4 Te2 Ching1 (pronounced Dow Duh Jing), which can be translated as Guidebook to the Way of Virtue (more commonly as the Classic of the Way [of both reality and wisdom] and of its Virtue [human application]). The Old Master (Lao Tzu, pronounced Loud-zz) wrote in a time and for a culture far separated from ours, but I believe his ideas fit everyday life here and now. Some people call this poem mystical, but I believe it is clear and eminently practical common sense. Lao Tzu never heard of capitalistic financial investing, much less the Dow-Jones Average of stock prices of major American industrial companies, but I have found that his principles assist in stock market investing. That application is what I call the Tao of the Dow, i.e., a Way to invest. The Tao Te Ching basically enunciates two primary principles which I will call Cosmic Harmony and Harmonious Balance. Flowing from these are the corollary principles of careful, open-minded examination of past and present, imaginative and prudent foresight, patience, self-control, economy of action, independence of analysis and decision, modesty, generosity of spirit, honesty, steadfastness in plan, and agility and adaptability in application.

A. Cosmic Harmony

By Cosmic Harmony I mean external harmony between the self and the outside world. This comes, not from mere lazy passivity or fatalism, but rather from closely observing reality and purposefully adapting ones own behavior to that reality. This examination of reality looks for truth, in the manner of a scientist, a judge, or a financial analyst. This adaptation is like that of the old-fashioned rag sailor, who depends on his sails to propel his vessel. He cannot get out and push the vessel; he has no engine on which he can turn up the power. Yet he does not passively drift wherever the wind takes him. Instead, he quietly and constantly observes the wind, the current, the waves, and the shore, and fine-tunes the position of his rudder and the trim of his sails to harmonize his vessel with the uncontrollable forces of nature to navigate his intended course. In a similar way, the prudent investor observes closely the geographical, political, economic, and psychological realities, the progress of particular products and companies, the trends of prices, interest rates, and so on, and acts accordingly.

8 Professional investors have a saying, The trend is your friend. Successful investors watch for trends and use them like a favorable wind. They dont fight the trend, even if it is only caused by a mere fad in the mass psychology of the market. Yet they keep attention on their goals and longer time periods, and remain ready to adapt to new information.

B. Harmonious Balance

The other major principle of the Tao Te Ching or Taoism is that of Harmonious Balance, or internal harmony. The ancient Greek Stoics called this same idea the golden mean, but most of us would call it the happy medium. The idea here is like the experience of Goldilocks (in the childrens story of the Three Bears), who tried food that was too hot, too cold, and then just right. The basic idea is to maintain personal balance. The most obvious investment applications flowing from this principle include: 1. First, the prudent investor tries to keep emotions in balance, because success depends on avoiding impulsive actions resulting from extremes of overconfidence when things are going well and of panic and despair on each setback. 2. Second, and related, the investor must position the individual portfolio as a balance to the market, buying what the market has neglected and selling what the market has overemphasized. This is called buying straw hats in the winter, when prices are low. 3. The portfolio itself needs to be balanced, as discussed below. Market terminology uses different terms for different aspects of this balance (asset allocation, diversification, cost averaging, etc.). At the opposite end of the civilized or developed world in the ancient classical period, the Greek Stoic philosophers also emphasized essentially the same guides to human internal and external behavior: harmonious balance and harmonization with the real world. The differences between the modes of expression of these two groups of philosophers do not represent real differences in the underlying ideas. The Stoics used the term Golden Mean, conceived as a middle ground between extremes, as the term for the goal of harmonious balance. The Taoists, by contrast, refer to the union or complementarity of opposites, but the idea is similar. Similarly, the Greeks tried to analyze and reason out the fundamental nature of the world, while the Taoists sought to be in harmony with nature, with the flow of natural events in the world. As any scientist or sailboat skipper knows, these two processes are essentially the same. One must be aware of and attentive to the principles or persistent tendencies of the real world (the scientific laws) and set ones mind and body in step in tune, in harmony with them to make effective progress. The Greek version of this principle of close attention to the real world has grown into the modern scientific method. The Taoist version has traditionally been associated only with a certain mental state sought for the sake of inner peace. Yet a few modern Taoist scientists have recognized the essential identity of the single principle underlying the two modes of expression of the importance of

9 close attention to the real world, undiverted by prejudices, preconceptions, labels, or opinions. We may briefly refer to this principle as that of cosmic harmony. These two guides to action can profitably apply to investment strategy as well as to other aspects of life, with effectiveness arising from the same qualities which make them so valuable in the phenomenological sciences and for psychological health, even though the earlier formulation of these guides did not specifically have securities investment in mind. Readers interested only in the practical application of this approach to investing in financial securities (stocks, bonds, cash equivalents, and derivatives of these) may skip chapters II and III, which refer to the general philosophy suggested here.

10

II. Harmonious Balance

A. The Unity of Harmonious Balance with Cosmic Harmony

One quality of cosmic harmony is conformity to the real nature of the world, implying common sense attention and adherence to reality. That quality clearly arises from the principle of attention to the real world and the effort to conform ones own thoughts and action to the pattern of the outside world. This does not mean passively going along, like the proverbial sheep; it means trying to learn what is real and to act in recognition of that reality. One of those realities is that people, like all forms of life, function best in a certain range of conditions. Outside that range come various degrees of discomfort, reduced effectiveness, and, at extremes, disaster. The middle of that range is the Golden Mean. If we are too hot, dry, stuffed, or oxygenated, we die. If we are frozen, submerged, starved, or suffocated, we die. Near those extremes we are uncomfortable and inefficient. Near the Golden Mean we are healthy and able.

B. Harmonious Balance in General

Thus, harmonious balance itself arises from cosmic harmony. Yet harmonious balance does not mean finding some middle ground and calcifying there. Staying in one situation at all times is also a kind of extreme. We need exercise for mental and physical health, but not to the point of exhaustion. We need mental concentration to develop our minds, but not to the point of utter frustration. We need a variety of kinds of food for health, and a variety in many aspects of life to make it interesting and enjoyable, and to maintain our ability to cope with changing circumstances and make the most of opportunities. In these respects, too, a human being needs balance not necessarily perfect equality of all aspects of life, because people differ in their need for and enjoyment of various aspects but sufficient variety to maintain interest, health, effectiveness, and adaptability. A human also needs a certain amount of stability in certain aspects of life, but the search for unchanging stability often leads to unfortunate rigidity, forcing oneself or others into unreasonable, even unbearable courses of action or experience, or to inability to cope with change. What one needs is not a single, immobile, rigid, dogmatic straight line, perfectly poised between unbearable extremes, but rather a dynamic equilibrium constantly correcting tendencies to excess. The chemical processes which characterize, maintain, and perhaps constitute biological life illustrate such a dynamic equilibrium. A living body cell is not limited to being able only and always to produce various chemicals at one rate. Instead, it has a variable capacity, and in practice produces more or less of each under varying circumstances. If some chemical which it needs and produces is, for whatever reason, being used up too fast or is still in inadequate supply, the cell will increase the supply. If some chemical is in excess supply, a healthy functioning cell will reduce its production. Thus, not by a rigid inability to change, but instead by constantly adapting to the actual situation, the cell maintains its balance. The Wright brothers may illustrate the same point in a different way. In the early years of experimentation with vehicles intended for flying, the principles of lift from air flow and the

11 consequences on the design of the shape of flying machines led to some fairly successful gliders. The invention of the internal combustion engine provided a light enough source of power. Yet early experimenters died in the attempt to build an aircraft stable enough to avoid tipping over and crashing. The important contribution of the Wright brothers was that they had learned from making bicycles not to think in terms of stability, such as a rail car gains by having four wheels, but in terms of continuous balancing, as a cyclist does. A bicycle is inherently unstable, but in motion is easy to keep balanced by positive balancing action. By observing birds they learned about steering a flying object, and used that learning to find ways to achieve a dynamic balance instead of static stability. From this finding they put together all these elements to make an airplane that not only flew but initiated an entire new and important aspect of human life in this world. These are illustrations of the goal of harmonious balance. In subatomic physics the nature of reality appears to consist in the interactions of discrete bits or packets of whatever composes the world and these appear to have a number of opposite characteristics. Electric bits are positively and negatively charged, different spin categories are recognized, etc. On a larger scale we are familiar with the north and south poles of magnets. These all seem to be opposite, or at least different, yet they are compatible they act together to make our world what it is. We do not need, and we would not want, to eliminate, say, all the negative charges in the world. A world of protons would not provide an adequate place to live. The harmonious balance of these opposites constitutes the core of reality and a healthy environment. A biological example was given above. Another is the presence of males and females in a wide range of species. The sex differences provide advantages to a species in adapting to changing needs. That advantage is so great that sex differences are fundamental throughout most of the more complex and even some of the simpler parts of the biological world. The mean or balance is not achieved by a single average form, but by a healthy dynamic balance between two (or sometimes more) rather different forms. The same principle applies as well at the psychological level. The stress of immediate problems may at times seem overwhelming. We may then rail against reality, but that behavior achieves nothing useful. Instead, we may retreat from reality. Yet a total and permanent rejection of reality usually also does not succeed, and often only worsens the problem. A brief retreat from reality may however be healthy if it means accepting the basic truth of reality but turning the mind briefly to other pursuits in order to regain ones mental balance and perspective, and rest it from discomfort. Hereby we can regain an internal harmonious balance. Similarly, the push of urgency or necessity or responsibility sometimes may make us push too desperately on others, passing on our tensions and emotional pain. If we can try to regain some of our own internal balance, and think about our effect on the world in which we live, we can make it better for ourselves and others. If we all or most of us do that, we shall all live in a world more like what we prefer.

12 We cannot eliminate emotion from our nature, and could not get much joy from life without it. Yet we can try to balance our emotions, so that we do not lose control and cause harm from venting an excess of anger, sinking to an excess of grief or despair, taking unreasonable risks in a fit of euphoria, losing the power to function in a paroxysm of fear or a cloud of depression, exhausting the body or psyche in some manic enthusiasm, or losing sight of crucial considerations in life through some narrow and obsessive fixation. Balancing activity and balancing thoughts can help to restore a degree of balance in emotion. The object is not a straight line of emotional death, but a damping of extremes and a balancing of the humps and swales toward a range of reasonable emotional health. At still more complex levels, the goal of harmonious balance is crucial for societies, of whatever size and complexity of organization. The modern invention of consciously written national, state, and association constitutions and charters attempts to apply some of what we have learned about this principle to social organization. (The same is true of statutes creating and constituting local and special governmental agencies, city and county charters, corporate charters and articles of incorporation and partnership agreements.) Power is centralized for certain purposes but with balance to prevent is monopolization and consequent abuse by any one element (or limited group of elements) within the society. We have not yet mastered this process fully, which should not be surprising since we have not yet fully mastered it at the simpler level of psychology of the individual human being. But we have learned much. The particular techniques of achieving the goal of harmonious balance in particular types of situation are the proper subjects of consideration by particular sciences and arts. The fundamental principle of seeking such a goal, and what we mean by such a goal, is a main constituent of the Way (i.e., the Tao). From harmonious balance flow patience, self-control, economy of action, modesty, generosity of spirit, steadfastness in plan, and agility in actions.

13

III. Cosmic Harmony in General

The practice of paying close attention to reality and of acting in accordance with what one learns is practical, and is what successful, healthy, and intelligent beings do naturally, whether they are human or not. Sometimes, however, 1. Their emotions make them forget what they have learned, or 2. Their circumstances become too complex for them to fathom, or, 3. If they are human, they are taught misleading and unhelpful ideas. The Tao attempts to return to basics, restore the common sense perspective, and deal with these problems. The goal of seeking harmonious balance is the attempt to overcome the first problem. The practice of observing reality closely and directly is the attempt to overcome the last problem and to cope with the second one step by step. Observing reality attentively does not mean merely looking at sunsets and rivers and mountains and other aspects of what we sometimes narrowly call nature. Everything that really exists is part of reality. Nature includes the tendencies of physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy, and geology, but it also needs to be recognized as including human nature (psychology), the nature of group behavior and of ideas (sociology), and the nature of reasoning and philosophy itself. We learn about reality from looking at all of these things, and from thinking carefully about (not their essence, as the Greeks tried to do, but rather) what consistent tendencies appear in their behavior. We seek to know, not what they are, but what they repeatedly tend to do. Trying to act in accordance with reality does not mean passively blending in, following the next person, accepting foolishness and cruelty, insensitivity and selfishness, or any other form of meanness of spirit, as ones own method merely because many others seem to regard that course as realism. It means looking at the capacities and needs of the real world and seeking to adapt ones own course so as to utilize these toward building an ever better life for us all. Cosmic harmony means fitting ones methods to the tendencies or laws of nature, including human and societal nature, to achieve ones individual objectives. That does not mean fatalism, saying nothing can change, for history shows that the most repetitive of all human and societal tendencies is to change. It does not mean following the current fads of diet or thought, for history shows that the most repetitive of societal tendencies is for such fads to change. (Such fads sometimes go to foolish and even unconscionable extremes.) It does not mean blindly following societys current direction, even if bad, under the excuse that I cannot make a difference among so many, because society is only made of individuals, and thus every continuity or change in the behavior of a society consists in what each individual human does. The push or urgency or necessity or responsibility sometimes may make us push too desperately to achieve some short term, highly personal or narrow-group objective, struggling to overcome nature or the natural processes. Western civilization tends to describe its successes as coming from such behavior. In fact, successes more often come not from opposing but from utilizing some natural law

14 to achieve a desired objective. We cannot, without excessive effort, stop the flow of a river; we can often use and redirect that flow in a more helpful direction. We cannot overcome gravity. We can, however, use it or some other principle, such as aerodynamics or buoyancy, to make a flying vehicle. Major social projects sometimes excessively disrupt pre-existing natural environments. The authors of the projects may feel that the value of the project outweighs the damage done. Indeed, it may. But often the damage done is inadequately considered and exceeds what was needed. A more careful plan might have gained much of the benefit without much of the social cost. Failure to observe reality often blinds us to the full range of consequences of a contemplated course of action. We only look at a narrow and see little potential harm. Those who think only of the next quarters bottom line, without regard to the public weal, fall uniformly in that category. Such reckless approaches lead often to wreckage of the very enterprise which undertook the action and for which the benefit was intended. A convenient or expedient or practical but anti-social or short-range action often leads to very impractical results for the doer in addition to the misfortune to his society. After all, humans live in societies because it is generally to their advantage to work for the common good. Each gains (or loses) from the action of each. Likewise, each part of the entire ecosphere affects every other part; all of life is in some degree a common enterprise. Certain competitions are practical among its parts, but not an action which tends to harm all life. The Tao Te Ching expresses these ideas more elegantly, more succinctly, and more poetically. Details of their application could be compounded infinitely. The wisdom of humanity consists in a very few principles learned slowly over the millennia, and a continuous process of rediscovering their applications to a never-ending list of circumstances. Here the only further examples will be more specifically those related to the application to investing of the two principles of harmonious balance and cosmic harmony. From the principle of cosmic harmony or conformity to reality flow the corollaries of (1) careful (and open-minded) observation of past and present, (2) logical foresight based on trend analysis, (3) independent analysis and decision, and (4) adaptability in action.

15

IV. Financial Securities Investing Defined

A. Investing

Investing here means setting aside a little of todays resources to increase tomorrows opportunities. It includes acquiring or improving some natural resource, creating or acquiring some tool, forming or obtaining an interest in some enterprise, acquiring some object or substance or right, lending something, or otherwise making some contribution to society or to the development of something which will be of value to society or some person. In current local usage it includes creating, buying, or lending some property. (The terms used here are to be considered in their broadest meaning. A tool includes anything of use to humans [buildings, clothing, roads, ideas, machinery, crockery, holding tanks, heating and communications systems, vehicles, etc.] A property includes both physical things and rights, i.e., privileges which society grants for some social purpose to its members and which they can individually buy, sell, lease, or otherwise use to increase their claim on the total benefits of society.) Some people characterize investing as gambling, but this is not an accurate perception. Investment always involves risk, as does all of life, but a sound investment is based on a careful and realistic analysis of actual information about the subject, including awareness of direction, velocity, and consistency of trends. In other words, in investing, we try to minimize the risk aspect. By contrast, the essence of gambling is maximization of risk and minimization of information on which logical judgments can be made. Indeed, possession of such information is considered cheating in a gambling situation, whereas failing to provide it is considered cheating in an investment situation. The original reason for the distinction was that all life involves risk but an effort to control it through knowledge, while gambling was specifically invented to make choices uninfluenced by knowledge, either to resolve conflicts without taking sides, or to learn the will of the gods. Only later did gambling become a conscious game. As a game it has the advantage, in theory, of making all participants equal, so that the weak or the foolish have as much chance as the strong or the wise. Now it is to a considerable extent a business enterprise by large organizations, which deliberately set the odds in their favor. In this form, what is gambling to the individual is sound business to the gambling house, the manufacturer of gaming machines, and the insurance company, because these businesses are able to play the averages and win. For them, that activity is economic. But in this sense they are not gamblers anymore they know what result to expect over time. The prudent investor takes risks but never gambles.

B. Financial Securities

By financial securities is meant interests in ownership, debt, money, their equivalents, and derivative interests. The basic securities are (1) shares of stock of business corporations and (2) tradable long-term debt of those corporations. A buyer of debt becomes a creditor of the company, and thus entitled to interest and principal payments from the company. Technically, tradable long-term debt consists of debentures, which represent unsecured debt, and mortgage bonds, which are secured by

16 the right to foreclose on certain property, such as land, buildings, machinery, aircraft, ships, railroad cars, etc., if the debt obligations are not timely paid. In looser usage, the term bonds often includes both types of debt paper. Stock includes both common stock, ownership of which may result in receipt of dividends and usually entails a right to vote for the board of directors and proposals to change drastically the nature and organization of the company, and preferred stock, which usually involves dividends of a specified amount out of profits, but no voice in most corporate decisions. Derivative securities include shares of mutual funds, which are companies, called investment companies, which invest in the shares or debt of other companies. Investment companies may be closed-end, meaning that they issue their own shares once at the establishment of the fund, and rarely after that, and trade in the market like any other stock shares (e.g., General American Investments, traded on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol GAM). Open-end investment companies, on the other hand, continuously sell shares in themselves to the public and buy them back in (called redeeming them); owners do not sell these shares to other individuals; and the number of shares outstanding thus constantly changes. Options are also derivative securities. In this sense an option contract is effectively an enforceable promise by one person, the option writer or seller, to obey anothers (the option buyers) demand to buy or sell a certain amount of the underlying security (say, 100 shares of stock) at a specified price. The writer is willing to make such a promise in return for a payment of cash (called a premium) at the time the promise is made. This premium payment is completely separate from any payment that must be made if the underlying stock is actually bought or sold. The demand is called exercise of the option contract, and must be made, if at all, only within a time specified by the original option contract. Option sellers do so mainly for the premium, hoping that exercise will not occur. Option buyers do so either for speculation to take advantage of price movements or for insurance against adverse price movements. The level and movements of the stock (or underlying security) during the life of the contract (between its open and its close) determine whether exercise of the option makes investment sense and hence which contracting party gains and which loses. The two types of option contract are named puts (buyers right to sell and writers obligation to buy the underlying security) and calls (buyers right to buy and writers obligation to sell the stock or other underlying security). An intermediary company sets the terms of the option contracts, but supply and demand determine the premium at which each trade occurs. Other derivative securities also exist. Warrants and stock rights resemble options, usually conferring a right to buy stock at specified prices, or to buy stock below market value, but their terms are usually set by the company which issued the stock. Indices are averages of various groups of stocks, weighted in various ways. Index options are option contracts similar to those mentioned above, but ties to the level of the pertinent index rather than to prices of individual stocks. Futures and commodity options may also be considered securities, but lie outside the scope of this manual.

17 Other categories of financial securities also exist. Unit investment trusts are like mutual funds, but differ in keeping essentially the same portfolio throughout the life of the trust. Partnership shares are sometimes traded like financial securities, but for reasons too complex to discuss here, I would generally avoid them, whether limited or general. My experience with them has not proven satisfactory. Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITS), which also trade like stocks, attempt to profit from real estate ownership or lending. These instruments will not be specifically discussed further in this manual.

18

V. Harmonious Balance in Investing

The goal of harmonious balance is crucial in investing in at least six respects: A. B. C. D. E. F. Psycho-Strategic Balance Emotional Balance Market and Selection Balance: Avoidance of Extremes Chronological Transactions Balance Portfolio-Holdings Balance Approach Balance

A. Psycho-Strategic Balance (Appropriate Goals)

The investor must adapt his/her investment philosophy, strategy, and tactics to his/her own individual objectives and personality. If the attempted approach is not in balance with the individual human outlook and nature of the investor, or is not directed specifically toward the individual investors real life goals, then the result will not be satisfactory. (1) In particular, in terms of goals, the investor needs to think about the relative value, to him/her, of: (a) Opportunity versus safety, of (b) Short term versus long term, in timing, of (c) Current income versus growth of principal, of (d) Current and likely future income, other resources, needs, and obligations, and of (e) Possible future needs arising from loss of employment or ability to work, funds needed for education, retirement, illness, and death. (2) An investor also needs to consider his/her own emotional (a) Level of patience, (b) Tolerance for volatility of price, (c) Ability to decide independently or accept advice, (d) Risk tolerance, (e) Interest and enthusiasm, (f) Diligence, and (g) Consistency.

B. Emotional Balance (Reasoned Action)

In abstract theory, investment should be approached logically, although, like much of reality, forecasts involve an element of risk (uncertainty). When a person has actually invested money, whether for oneself or for another, however, emotion tends to become deeply involved. Consequently, when prices are rising, the investor tends to become overconfident and buy eagerly, even recklessly. Because this is happening to many people at the same time, the euphoria all around tends to exaggerate the effect on the individual, and on the market in general. Similarly, when prices fall, the investor may tend to lose confidence, even to panic, and sell when prices are low. The consequence is a strong tendency

19 to buy when prices are high and sell when prices are low exactly the opposite of a successful investor who, by definition, buys low and sells high. Of course high and low are relative, and in retrospect may seem very different from how they seemed at the time. The important point, however, is that emotions tend to motivate us to do exactly the opposite of what is prudent and sensible. An important principle in investment buying and selling therefore is to keep the emotions in balance, or at least exercise self-control over actions: avoid manic (reckless) and depressive (panicky) actions. Do not become overconfident no one and nothing can climb to the sky; do not become overly discouraged the world is not yet about to end. In either case, the market will turn. There are times when a recent price rise implies a future price rise, or a fall suggests further falls, but these must be evaluated by reason and not by emotion.

C. Market and Selection Balance (Independence, Avoidance of Extremes)

For the same reason as outline in section B, the market (the general tendency of prices) tends to go to extremes. Prices will rise farther than is reasonable, then fall farther than is reasonable. This tendency creates risks sometimes prices are too high for a purchase to work out well, sometimes too low to permit a reasonable gain from a sale but it also creates opportunities (buy when prices are too low, sell when too high). Essentially, the principle of balance dictates avoidance of extremes, whether in ones own psyche or in price levels. The exception is the investor who is doing the opposite of the markets tendencies, because here another kind of balance is in play: the market will ultimately balance itself by swinging back and the individual investor can gain by balancing out the market extremes. Great caution is needed in doing this, however, for there are risks to going against a current trend. Thus it is important to recognize extremes. The reasonableness of a price depends ultimately on fundamental analysis (see below), but the technical analysis is particularly valuable for determining trends, extremes, and likely turning points. For example, when everyone seems overoptimistic and prices (or a particular price) are unreasonably high, or when prices (or a price) rise at an accelerating rate, it may be time to stand aside or even sell; and vice versa. This principle applying to the market in general, also applies to individual securities, especially stocks, mutual funds, and options.

D. Chronological Transactions Balance (Cost Averaging)

Partly to avoid the excessive effect of emotions and partly to avoid the pitfalls of unexpected or unforeseeable market-trend shifts, a wise procedure is a measured pace of gradual change of investment stance: if an investor wants to buy (expecting a sustained rise in the whole market or in a major part of the intended investment portfolio), gradually buying in over a period of time (months or years) is often prudent (called cost averaging); likewise in selling, expecting a major market decline, it is sometimes useful to sell a little at a time, gradually over time.

20 These procedures require self-control and patience, do not suit everyone, and are not always appropriate (especially where the particular item is to be only a small part of the total investment portfolio), but I believe they produce superior results when an investor is trying to time a primary (relatively long term) market change or moving into a particularly risky investment area. When buying of a single security is done at exactly equal intervals of time and in exactly equal dollar amounts, purchasing in this measured, balanced way is called dollar cost averaging, and is common in acquiring substantial holdings in mutual funds, but it is just as sensible in moving into an industry and moving between different major asset-type allocations. When it involves buying more shares when a stock falls, it is called averaging down; when it involves buying smaller amounts as a stock rises in price, it is called pyramiding. In selling, it has no name, but all of these examples are applications of the same idea, which is balance in the timing of major changes in the investment portfolio.

E. Portfolio-Holdings Balance

Because no one can forecast the future with absolute certainty, some allowance must be made for the unforeseeable. The solution is not a search for the absolutely safe investment, like the search for stability in early aeronautics; as in the case of the Wright brothers, the solution instead is a dynamic balance. Viewed another way, balance in the portfolio allows the investor to gain from one class of investment to offset potential losses in another. There is no safe investment. Stocks can grow more than most investments, but call fall rapidly, and do so at irregular intervals they tend to be volatile. Bonds vary less in dollar value, but may lose in purchasing power when inflation occurs. They also change value depending on prevailing interest rates. Money-market funds are liquid and retain dollar value essentially unchanged, but deal with inflation even less well. Several kinds of balance are needed in a sound portfolio. The appropriate proportions of each element of the balance varies according to the needs, resources, and personality of the investor. The various facets of such portfolio balance are outlined below, with their customary names as used in the market. 1. Asset allocation: shifting trends among: a. Equity (participation) in enterprise for profit (=stocks), which also come in severl classes, among which a portfolio should be properly balanced: (1) Cyclical (rise and fall with economy); (2) Growth (tend to grow at most or all times); (3) Growing income (utilities); b. Debt (=bonds) provides fixed income, sometimes capital increase; one must vary maturity dates; c. Cash equivalents (=money market funds, etc.) Provide liquidity for emergencies or opportunity or allow waiting in time of uncertainty; provide limited interest; d. Physical assets, which protect against massive inflation:

21 (1) Real estate (2) Gold, etc. 2. Diversification a. Different types within each asset allocation (growth, cyclical, emerging, yield stocks; or bonds of different degrees of credit risk, different maturities, different debtors, etc.) b. Different industries c. Different companies d. Contra-cyclicals, i.e., companies whose individual cycles tend to offset each others cycles (for example, gold mining companies versus interest-rate sensitive companies, heating supplies with warm-weather products, etc.) 3. Geographic balance a. Different localities for local public utilities and regional banks b. Different global regions for world-class stocks 4. Risk balance: foreseeing the unforeseeable (because the future is never fully foreseeable, it is prudent to balance obviously riskier investments entered for their greater potential gain with apparently less risky investments, and keep the former to a limited percentage of the latter.) It is also prudent to provide protection against each of the major risks: a. Market or volatility risk (prices rise and fall); b. Credit risk (debtor doesnt pay); c. Interest rate risk (interest rates may rise, reducing value of existing long-term bond); d. Currency rate risk (risk that currency in which the purchase is denominated [e.g., marks or pounds] will fall relative to that which the investor must use to live [e.g., dollars]); e. Inflation or purchasing-power risk (prices for particular goods and services used by the investor may rise more than the value of the security); f. Quality risk (investment may simply prove less valuable than expected because the issuing entity is not as economically sound as expected).

F. Balance in Approach (Adaptability, Flexibility)

Whatever approach the investor or trader takes in all of the above mentioned respects, occasions will still occur when a change of direction or portfolio proportions or methods will be needed. Balance in approach means avoidance of rigid attachment to a single approach. An investor needs a consistent, basic strategy, but must maintain adaptability and flexibility in details, making reapportionments from time to time (especially in different phases of the economic cycle or of company development), and dealing with new circumstances as they arise, whether in the nature of new problems or new opportunities. The Tao Te Ching and other Asian scriptures speak of avoiding attachments to things. In the mundane practice of investment, the prudent investor avoids falling in love with (becoming emotionally or habitually attached to) one stock or tactic, to the point of using it at an inappropriate time.

22 Balance in tactics implies modesty about previous positions and expectations, patience coupled with adaptability, self-control, generosity of spirit toward trading partners (the other side in the contract), economy of action, and a balanced plan steadfastly applied.

23

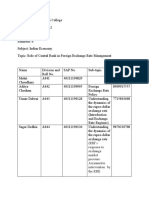

Diversification among Stock Types (above) and among Growth Stocks (below).

24

25

VI.

Cosmic Harmony in Investing:

A. Initial Comments

As indicated above, by cosmic harmony is here meant conforming behavior to fit reality. Aside from avoidance of wishful thinking and emotional responses, the difficult part of this process is discovering reality and its significance. The universe is whole and interacting, so everything influences everything else. Humans, however, with finite minds, cannot absorb the whole; we must settle for bits and pieces of information which we evaluate in light of each other and of past experience. We therefore never have enough information, but life requires decision on the basis of this limited information. We therefore must make judgments on how much effort to devote to gathering information, determining the relative weights to assign to various parts of it, and elucidating the relationships among the various parts of our data. A successful search for truth, for reality, requires intellectual honesty, independent analysis, and ignoring prejudices, preconceptions, labels, and opinions. We have to look beyond the words to objective reality. Discovering truth leads to the old conclusion that honesty with others, humaneness or generosity of spirit, and the golden rule, regardless of temporary temptations, really do constitute the best long-term policies, which do not permit exceptions. A reputation for honesty has great value, but a single breach will destroy it beyond repair. Factors most pertinent to financial securities investing are: 1. The background milieu, including such subjects as a. Economics (1) World (2) Regional (3) National (4) Provincial (5) Local (6) Enterprise b. Politics (1) Policies and practices of official government at all levels (2) International trends and demands c. Resources (1) Social Policy (2) Physical resources (3) Routes (Many other background factors are also relevant but not discussed in detail in this little book, such as the fundamental directions and current status of science, technology, education, demography, etc., and particularly the geographic, chemical, biological, sociological, and ecological facts which affect human life.) 2. Fundamental Analysis

26 (the attempt to discover true value of a security, relative to other investments, on the basis of actual and projected business considerations) 3. Technical Analysis (the search for patterns of mass psychology affecting prices of financial securities)

27

VI. Cosmic Harmony in Investing, Continued

B. Environment

1. Economic Environment a. Nature of Economy The nature and current status of the general economy in which investment is under consideration is obviously a crucial aspect of the investment environment. Ours is a mixed economy, in which several types of organization operate: (1) Individual autonomous subsistence activities (such as hunting, fishing, gathering berries and roots, etc.) which may involve sharing (within the family unit), but do not involve formal exchange this form of organization, unlike all the others mentioned here, is disregarded in virtually all national economic statistics and is not subject to the laws of economics taught in the schools (all others below are); (2) Individual and family enterprises, in which one person or family provides all the labor and capital, but the product or service is exchanged for money or barter; (3) Cooperatives, in which several humans participate as approximate equals, with various kinds of organizational structure; (4) Sole proprietorships, in which one person owns and manages the enterprise, though often borrowing funds for capital and hiring employees for labor; (5) Partnerships and joint ventures, in which more than one person operate the enterprise jointly, sharing profits, losses, investment, management, and liability to lenders, suppliers, employees, and customers, operating otherwise in a manner similar to a sole proprietorship; (6) Limited partnerships, in which one or more partners have management and liability, and others merely invest for a share in profits; (7) Corporations, which have the status of separate legal persons functioning like sole proprietors, but operated like a sort of subsidiary state, with a ruling group (board of directors) elected by the investors (shareholders) overseeing officers and a general manager (chief operating officer or CEO); (8) Associations (such as clubs), a form of little interest here; (9) Trusts; and (10)Public entities, such as governments of national, state, and local jurisdiction, schools, libraries, hospitals, research institutes, etc. Think tank futurists now argue that future enterprises will be characterized by more equality among the humans comprising the enterprise; more individual autonomy and initiative; flexibility; more widely distributed decision making; and perhaps a more responsible approach to the common good than has generally characterized business enterprise in the past.

28 b. Financial Securities: Relationship to Organization Forms Financial securities generally arise from the activities of business corporations owned by groups of individual humans, usually in considerable numbers, and by retirement funds, trusts, and other corporations. c. Classic Economic Laws In our society, some classic economic tendencies have been noticed. These were largely described by Adam Smith or others in the period (though some of these principles were known before that) when physicists were discovering the gas laws and atomic theory, and are therefore phrased in language and concepts similar to those scientific laws, i.e., they assume a perfect system with no friction, composed of elements of infinitely small size. Just as Boyle and Charles described how the atoms in a gas act, treating the atom as having no size (a point moving in space), Adam Smith describes an economy on the assumption that no individual enterprise or source of economic activity or resources is large enough for its size to matter, with each able to move infinitely far in a trivial time. This approach sufficed for his time, because his purpose was to ameliorate the economically stultifying restrictions imposed, and the special privileges and favoritism granted, by royal governments. For our time this simplicity in theory hides some defects in the analysis, but, keeping the limitations in mind, we must remain aware of the fundamental observations of classical economic theory: Law of Supply and Demand: In a totally free, equal, and competitive economic system, the price of a commodity, service, or other economic good depends (in part) on the supply (wide, easy availability tends to reduce price) and (in part) on effective economic demand (the desire to have it, coupled in the same person with the ability and willingness to pay for it). Demand, in this instance, depends not only on human needs, perceptions, and desires, but on the presence and distribution of buying power, which in turn depends to a considerable extent on the preservation and distribution of the results of prior production. The extent of price variability differs, however, from one type of economic good to another, depending on the flexibility or elasticity of supply and of demand. For example, in a hot country salt may be a necessity; therefore demand will always be relatively high; the amounts of salt obtainable are limited to some degree by mother nature; and therefore the price is unlikely to fall too far. On the other hand, some fad item or more discretionary purchase may have a great elasticity of demand, commanding a very high price at one time and place and an extremely low one under other circumstances. Each potential buyer has a series of prices at which that person is willing to buy certain amounts of something, and each seller similarly will sell different amounts at different prices. At some prices the seller may be unwilling ever to sell any, because the cost of production to the seller is too great to allow such a sale to be worthwhile or even acceptable, and at some prices the buyer will not buy. These series can be represented graphically as a series of points (or a curve in algebraic language). Sales occur, theoretically, at prices and in quantities revealed by the intersection of these curves. These intersection price levels are called the equilibrium prices because at these levels the supply and demand are in

29 equilibrium with each other. Different prevailing price levels may cause different amounts of a good with high demand elasticity to be sold. Actually, Adam Smiths idealized, atomic economy differs from reality. To some extent, custom, regulations, subsidies, tariffs, discriminatory taxes, waste, uneven economic policy, frictions and distortions in the market, market power such as monopoly or oligopoly (limited suppliers available) or monopsony or oligopsony (limited customers, such as only a single user, e.g., a unique business or a government) will also influence prices, as will a government requirement of having that good (such as automobile public liability insurance). In fact, any actual substantial size of any market participant distorts to some extent the operation of the market, as does geographical distance, local licensing, and other factors. Allocation of Resources: The existing price levels tend to influence the use of the resources of an individual customer or worker or investor, of an enterprise, of a country, of an economy, particularly where less expensive substitutions may be made. Of course quality of a potential purchase item also plays a part. The supply and demand curves may be analyzed in terms of value from the viewpoints of buyer and seller. The buyer must consider how much he or she has available to spend, what other demands there are on those limited resources, how much is likely to come in the future and at what rate, whether prices are likely to rise or fall or stay the same, how urgent the purchase is, what benefits it will provide, what opportunities are lost by spending the money or other resources on this purchase, etc., in light of the marginal utility to the buyer of both the purchase and the wherewithal to make that purchase, The seller must consider the costs of production (or acquisition by the seller from the producer), how urgent the sale is, what is likely to happen to price in the future, the cost of carrying the item in inventory (if it is carried), etc. Each must seek to obtain the maximum utility available to that party from the transaction. The trade can be mutually beneficial, and is likely to be consistently repeatable only if it is mutually beneficial. Trade versus Subsistence or Autochthony: A system of specialization and exchange increases productivity and prosperity over a system of self-sufficiency. Hence wider free-trade areas commonly lead to higher prosperity. When internal tariffs kept China, France, and Germany backward a few centuries ago, their absence helped Britain to lead the world economically. The unification of Germany in 1870 brought it ahead of Britain, and when the U.S. grew larger, it became the leader. The European Economic Community and China today are making strides from their more recent movements toward internal economic unity. Inclusion pays. Exchange of ideas, too, leads to more efficient advancement of more useful ideas. Where ideas from different cultures cross at some country, whether because of trade, exploration, or education from other kinds of impetus, that country often becomes the dominant culture of the time. Such has happened many times in history. It also happens in business and science. Persons from different scientific disciplines or different industries often find ways to make a company or a field of research prosper from the interaction of these divergences and exchanges.

30 For this reason, attempts to monopolize or corner the market sometimes backfire. Open architecture in computers led first Commodore, Apple, IBM, and later Sun to prosper, because of the wide range of software which outsiders quickly provided to operate on machines produced by these companies. Texas Instruments attempt to corner the market in TI software effectively killed the sales of the previously popular TI home computer and drove TI from the industry. Elements of Production: Economists generally recognize that production of goods, or even of services, requires the input of human effort (labor), natural resources (land), and capital, but not all define these terms in the same way. Many say that capital is, effectively, money, because money can often be exchanged to obtain real capital. Accountants treat money as capital, so that both long-term borrowing and saved profits, as well as initial investment in a company, are lumped together as capital structure. Other economists mean by capital the means of production saved from prior production, which for most businesses means the machinery and other equipment, special rights and privileges (such as patents, franchises, buildings, roads, electronic systems, information, etc.), and similar things used to aid labor in accomplishing the goals of the enterprise. This is, economically, probably a more useful definition. A whole country can only slowly convert money into usable capital equipment, although a single company may be able to do so fairly rapidly. Some economists include natural resources as capital, because certain systems allow them to be bought, and also because prior work may alter the immediate practical availability of some natural resources, but other economists distinguish irreplaceable natural resources as a third separate element. Since the other two elements can be changed by economic activity, and natural resources, in this sense, cannot, the separate treatment of this element is probably a sounder approach. A few economists list entrepreneurship as a fourth factor of production, but this concept seems to mean merely the investment of time, effort, initiative, leadership, and control exercised in varying degrees by some business owners, which are all forms of service, i.e., labor; investment of money or land or capital, which are already included in the other factors; and assumption of risk if the enterprise does not do as well as planned. But all participants experience risk, so this is probably not really a separate factor. In economic theory, the factor payments are termed rent if for natural resources and sites (land), interest if for capital lent with a promise of return, profit if for capital contributed as part of ownership, and wages if received for any form of service. Common usage slightly alters the applications of these terms, but in economics each must be taken into account. Each of these interests, if paid for, constitutes a part of business expense, and therefore helps determine the prices at which a seller is willing to sell. Law of Diminishing Returns: Because a number of factors affect each part of the economic process, an increase in one may often result in higher production, but this effect will be strongest when the increase is in the production element which is currently the most limiting factor. When there is a surplus of one of the three elements of production, increasing that one will not increase production

31 much. Thus, if labor is in short supply, but there is plenty of equipment and natural resources are plentiful, one more worker (if healthy, intelligent, and properly educated and motivated), will increase production considerably. But if capital or resources are in short supply, one more worker will not add much production. Thus, if the one element of production is increased and the other two are held constant, there comes a time when each further addition to that one element will add less production than did the previous addition. This is the law of diminishing return. It leads to the Law of Marginal Utility or Cost, meaning that at some point a further increase in the surplus element of production will add so little production as not to be worth doing it the point of marginal utility. Some companies find a way to sell a significant part of their products at prices sufficient to cover fixed and variable costs, and in addition sell some (in a different market) at a lower prices, determined by the law of marginal utility, usually the variable cost without regard for fixed costs, which are unaffected by how many units are sold. Scarcity: Economists say there is scarcity because reality is always finite and human desires tend to be infinite, especially so in an advertising society. Hence, total wants tend to outdistance current availability of whatever people want. Bad money drives out good: If two forms of money both suffice as legal tender and one is less valuable, or holds its value less well, everyone will pay bills in the less desirable form and hoard the other, driving it out of circulation. This was more important when gold and silver, though having variable values like any commodity, served as money, at a set ratio. Now it is replaced in importance by currency-value ratios. A rising economy and higher interest rates will tend to make one currency more attractive and therefore rise in value relative to another (say, the mark versus the dollar versus the yen versus the pound, etc.). The weak currency is sold to buy strong currency to invest in the stronger economy or at the higher interest rate, further draining money from the weaker economy. The devalued currency, however, then effectively makes the prices of goods produced in the weaker economy less expensive in international trade terms, which may tend (usually only temporarily) to improve sales of such goods and thus improve the weaker economy. Inflation usually increases in the economy with the weaker currency. Economic Stages: Since humans have considerable capacity to recognize improvements in methods, a common historical sequence of development of manufacturing in a country or region is from primary industries derived from and immediately dependent on natural resources and crops (such as textiles, wood products, metallurgy, processing of food, fiber, and fossil fuels), through secondary industries (like vehicle, chemical, and other more sophisticated manufactures) to tertiary industries with most advanced technologies (currently electronics and gene-splicing, but later something now unforeseen). Commercial activity often garners better profits than manufacturing and the latter more than agriculture per person engaged in them and per acre devoted to them, but in each case only if a large enough hinterland or market area is accessible, in which the other, more basic industries still prevail.

32 International specialization: In an ideal economic world, i.e., one without wars, national subsidies, and obstacles to international trade, each nation, like each individual, would, according to economic theory, fare better trading freely with all others, producing what it produces most efficiently, and buying from others what they produce most efficiently, because that arrangement yields the highest productivity and efficiency, coupled with the lowest prices. The major obstacles to such an arrangement, however, are (1) inertia, because current change from a different arrangement creates current disturbances and dislocations during the adjustment process; (2) the perennial effort of each to gain advantage over others, urging others to open their markets while restricting or skewing its own; (3) the inability of workers to move about to get work or access to resources, as easily as money and trade move; (4) the lack of effective international monetary and regulatory standards; and (5) the threat of interruption of supply, particularly from wars. If a group of nations can agree on avoidance of war among themselves, and provide a mechanism to assure that arrangement, and to protect them all from outsiders, they could then dare to trust their economies to one shared economy. The world slowly struggles toward this goal. Private Enterprise: The value of so-called private enterprise lies primarily in allowing competition of methods and relatively objective measurement of efficiency by profit. Yet its social costs (damage to workers, neighbors, sometimes customers, environment) become excessive if government policy fails to assign those costs to those competitors who create those costs. Hence this system only produces a consistently satisfactory result if government performs that assignment adequately. Workers compensation programs, product-liability and environmental lawsuits, health and safety regulation, and similar programs constitute attempts to accomplish that assignment. Common Observations Outside Classical Economics: Honesty and fairness in administration yield higher efficiency in the economy. Where governmental or company officers abuse their position for personal gain at the cost of the society or the enterprise, the latter loses efficiency. Irrational and unjust discrimination hurts perpetrator, object (intended victim), and bystander. Those societies and companies which have not learned this are less promising places for investment than those which have learned and consistently applied these principles. This paragraph may sound idealistic, but history proves its serious practicality, and investors often rue having ignored these commonplace ideas. d. Effective Demand The environment in which a company operates obviously can affect the success of the company, and the most obvious pertinent aspect of the environment is the economic. Markets, meaning demand for products and services are particularly vulnerable to the current general health of the economy. A maker of factory machinery will sell more when other businesses expect to expand their sales and therefore need new machinery; a builder will sell more houses when people are able to buy them; a seller of clothing and entertainment will make more sales when more people are able to buy them. When times are bad, these kinds of sales will fall drastically. Ability, desire, and confidence among buyers are not precisely constant in respect to those kinds of purchases which can conveniently be delayed. The rise and fall of economic demand largely

33 determines the level of consequent economic activity aimed at satisfying that demand. Increasing efficiency of production or supply can increase the buying power of either producer or customer or both, depending on how that efficiency is used and how the proceeds of it are allocated, but the ability to buy constitutes a crucial aspect of effective economic demand. Those who do not have the means to buy cannot do so, however much they may want and need to do so. Ability to produce is therefore crucial to economic health, but so it effective economic demand. In modern industrialized countries, therefore, effective economic demand generally controls the level of economic activity. The rise and fall of effective demand produces the rise and fall of economic activity, to which we refer as booms and busts, or growth and recession, etc. This rise and fall continues in all economic activity, at varying rates of change and over varying periods of time. Some broad tendencies seem to dominate for certain periods of time, however, and the general level of the economy tends to affect individual companies and humans. Interest rates, wars, natural disasters or unusually favorable natural phenomena, new inventions, new discoveries, new methods, and other factors can affect these broad economic fluctuations. The institution of several social insurance programs during the generation after the 1930 depression in the United States, for example, has tended to balance out and soften the effect of adverse circumstances since then, keeping the economy from sinking excessively low excessively fast, so as to allow government and businesses time to survive through temporary problems and to correct more lasting ones. Still, if the respite provided by these programs is not utilized to overcome basic problems, the results may prove unfortunate. If an individual company does not adjust its methods to a changed world in which it finds itself, its decline is assured. If a nation does not correct fundamental defects during the respite, its future will be difficult. The principles of the Tao and of common experience favor allowing the people flexibility and the freedom to adapt to reality as their many eyes see it, but also requires protection to all from each, and that no minority may seize so much that the rest cannot survive or feel that they have no stake in the benefits of their society. Each should be allowed what that person earns, but not necessarily all that the person can lay hands on, and all must contribute in accordance to their ability to those common expenses which society can best provide in a common effort. Social costs incidental to business activity will only remain within reasonable bounds if those persons or organizations with power to control them have to bear them. For example, rates of worker injury are largely determined by the nature of an economic activity and by the policies of company management. If the resulting socio-economic costs are borne by the company, it will be encouraged to keep them within reasonable bounds, either by more safety-conscious policies (such as fenders or enclosures over dangerous moving parts of machinery) or by safer manufacturing techniques (such as use of robots for dangerous work, or a substitute product allowing a different process). e. Organizational Flexibility and Social Inclusivity We also need to allow a variety of approaches. The Tao opposes straining to attain some overabstracted, oversimplified, rigid system. Such systems always become tyrannous, whether they are

34 extremely chauvinistic, selfish, or socialistic. An unbalanced system, which tries to force all group projects into one kind of organization, becomes unnatural, oppressive, inefficient, and ultimately insupportable. A one-legged stool is unstable. Some needs of society are best provided, as experience has shown, by public institutions: (1) military, police, and other regulatory organizations, because those not under public control cannot be trusted with power to coerce their fellow citizens; (2) at least a certain level of education, because it is in the interest of society that all citizens reach their maximum potential, regardless of whether individually and unaided they have the means to do so; (3) public roads and other facilities, because everyone must have access to them, because establishing them involves the power to take or spoil privately owned land, and because the taking of tolls impedes the flow of traffic. Public assistance to the destitute and other unfortunates has become necessary because those most able to help them tend not to do so voluntarily on an individual basis to a sufficient degree, perhaps partly because our competitive system tends to penalize them for doing so. Still, some social needs are best provided by separate, competing enterprises. Competition, where it stays within the bounds of efficiency, quality, service, or even educating the customer to the value of a product, provides an objective measure of the success of techniques, and thereby can reduce excessive bureaucracy, correct inaccurate judgments and forecasts, reward initiative and perception, and thus improve the economy generally. The danger is from the short sighted, who seek quick profit through fraud, overreaching, shoddiness, planned obsolescence, and dangerous practices; from the narrow viewed who injured their neighbors, their environment, their employees, or their society through disregarding the interests of these; from the vicious, who abuse for other ends the power granted them to operate enterprises; the dishonest and unpatriotic who injure their society by shirking their tax, regulatory, and other social responsibilities; and the grasping who abuse their power, acquired for management purposes, to garner an excessive part of the returns from shared enterprises. Some of these separate enterprises are actually private, one-person projects, but most economic activity in industrial countries is carried on through large-group organizations such as corporations and cooperatives, often with many employees, many stock holders, many bond holders, many customers, and many suppliers: a team requiring teamwork. A society needs to protect itself, its citizens, and its valuable institutions from enemies and to provide its members a sense of self-worth, but some societies are excessively narrow and domineering, too exclusive of other societies, or even of various segments of the society itself, whether on a genetic, religious, linguistic, or other physical or cultural basis, or just on the basis of some more trivial definition of ins and outs. All of these tendencies in societies have their useful, worthwhile side, but any society which tries to press every aspect into one of the three extremes (of excessive public enterprise, excessive private enterprise, or excessive regulation) falls ultimately on hard times and creates great, needless misery in the interim. Every society needs all of these, mixed and melded in suitable proportion civic

35 organization, privately owned (but often shared) enterprise, volunteer organizations, individual activity, working in harmony, each in its proper sphere. Wholeness comes only from the union of divergence; health comes only from the balance of multiple functions. An unstable or unbalanced society will not provide a secure investment milieu. Hence, a prudent investor will tend to invest more in societies with these various favorable features and even consider them in evaluating the effectiveness of the internal organization of a business corporation. f. Economic cycles

For financial investment purposes, then, the prudent investor must examine the state of the economy at any given time, look for the direction in which it is moving, as a whole and in its principal parts, up or down, and for its health or soundness, its balance, and whether it can continue to progress as it has. If the economy is rising and sharing the rise broadly, building soundly for the future, investment in stocks for growth may be profitable. If the economy is declining, then investment debt may be sounder. If inflation has become, or is likely to become, rampant, investment in land and physical objects may be best. If the economy is superficially doing well, but its benefits are flowing into increasingly narrower channels or growth comes only by enlarging debt faster, or economic growth is exhausting a crucial resource like forests, soil, a mineral, or the good will of its own people or its neighbors, then the prudent investor knows a time of retribution and tribulation lies ahead, and plans for it. The prudent investor also looks for how to utilize the observable trends in the economy. If interest rates are about to fall, buying bonds may produce substantial and prompt returns. If productivity is rising and depressed conditions are about to improve, stocks may be better. If inflation and recession are to be combined, physical assets may be needed. If a quick and temporary drop in prices is about to occur, cash may be best. If leisure time, disposable income, number of households or children, accessibility of resources or tourist locations, or something else is increasing rapidly, an industry able to utilize that change to its advantage may offer appropriate investment opportunity. If one industry is making another, or a part of it, obsolete, prudence suggests avoiding or deleting the loser from the portfolio. Generally, at any given time, some parts of the economy will be growing while others shrink. In general, three major price cycles overlap in our current economy: those of stock prices, of bond prices, and of physical assets. When economic activity is rising, or is soon expected to rise, business enterprise profits are generally expected to rise. People therefore invest in ownership of those enterprises. For most of us, that means buying stock. This causes the prices of stocks to rise, as demand for stocks increases faster than supply. In practice, the stock price rise tends to begin an average of six months before the actual economic rise, because investors are trying to forecast the future of prices. Individually they make many mistakes, but en masse their combined transactions function together like a massively parallel computer, which forecasts reasonably (but far from perfectly) well.