Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Doing Business in 2012 Case Studies Mexico

Uploaded by

sanjay NayakCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Doing Business in 2012 Case Studies Mexico

Uploaded by

sanjay NayakCopyright:

Available Formats

32

DOING BUSINESS 2012

MEXICO: UNLEASHING REGULATORY REFORM AT THE LOCAL LEVEL

Governments around the world face challenges when pursuing broad regulatory reform: identifying bottlenecks, obtaining political support, getting the resources needed, gaining buy-in from stakeholders, bringing agencies together in one coordinated effort. Mexico illustrates the challenges of regulatory policy making when it involves different levels of government and regulation. Mexicos 31 states and 2,441 municipalities, along with Mexico City, have extensive regulatory powers, allowing them to design, implement and enforce regulations.1 So regulatory reform has required not only horizontal coordination among ministries, agencies, and legislative and judicial bodies at the federal level, but vertical coordination with entities at the state and municipal levels. The regulatory reform initiative in Mexico has used an exercise of benchmarking business regulation in all 31 states and Mexico City to support this coordination and stimulate change.

no longer viable. Compounding the problem was the lack of outreach to other stakeholders: Congress, the judiciary and the public administration.3 In 2000 the Office of the President set up the Federal Commission for Regulatory Improvement (known by its Spanish acronym Cofemer) with the aim of establishing a long-lasting reform effort and a systematic approach to regulation. But while this agency became the main driver of change, continuing political obstacles at the local and national levels limited its effectiveness. In late 2003 the rst Doing Business report ranked Mexico above the global average on the ease of doing business. Yet Mexico trailed behind such competitors as Chile, Malaysia and Thailandand even further behind OECD high-income economies such as the United Kingdom, Australia and Germany. The Office of the President saw an opportunity to use the Doing Business report to drive improvements. But because the presidents support in Congress eroded even further in the 2003 midterm elections, reforms failed to pass. With a national presidential election looming in mid-2006, the Office of the President simply did not have the political clout to carry out broad reforms, which usually take several years to plan and implement. Thanks to Mexicos federal structure, however, states could start reform efforts immediately. In 2005 the Office of the President requested a subnational Doing Business report that would go beyond Mexico City. The rst such report, launched in 2005, benchmarked 12 states in addition to Mexico City. A second one extended coverage to all 31 states in 2006. A third report repeated the benchmarking in 2008. A fourth is under way.

Sharing experience

The subnational Doing Business project has provided a vehicle for peer-to-peer learning and sharing of good practices among Mexican states. Cofemer organizes a conference twice a year at which plenary sessions allow every state to share its experiences with regulatory reform, as well as lessons learned. Peer learning also takes place even more informally, on visits by policy makers to good performers such as Aguascalientes and Guanajuato. A visit to Sinaloa, where policy makers learned more about how this state issues land use authorizations electronically, led Colima to set up a similar system on its own website. Sharing experience makes sense, because differences across states in what entrepreneurs encounter in doing business can point to opportunities for improvement. For example, Doing Business in Mexico 2007 showed that business registration fees varied greatly from state to state. In Michoacn the registration cost for companies was the equivalent of $16; in Chihuahua it was $1,035, more than 60 times as much. And while some states set xed fees, others charged percentage-based fees, calculated on the basis of the companys capital.4 The 5 states with the most expensive business start-up processes used percentage-based fees.5 The story was similar for property transfer fees. Yet a company registration or property transfer takes the same amount of work regardless of the size of the companys capital or the value of the property. The many similarities across statessuch as bottlenecks faced by entrepreneurs trying to start or expand a businessprovided just as much reason for sharing experience. In registering a business or transferring property, the biggest hurdle was ling documents with the company or property registry. Doing Business in Mexico 2007 reported that the property registration procedures with the public registry took between 73% and 87% of the total time for registering property. But Doing Business in Mexico 2009 could report that 13 states had focused on updating their property and commercial registries. Many states have also been working to consolidate procedures in one place. Most now have a

Gathering momentum

Regulatory reform efforts started as early as the 1980s as Mexico, seeking rapid integration with the global economy, joined large international trade agreements and the OECD. Greater openness to international markets and increased competition required measures to lower the cost of doing business for its 75 million people.2 In the early 1990s the reform initiative was led by the Office of the President and a small group of technical advisers. The consequences of the 199495 economic crisis helped intensify the focus on small and medium-size enterprises as an engine of employment growth. But the success of the reform efforts was undermined by lack of effective monitoring, transparency and public support. Changes in the political landscape after the 1997 midterm elections weakened the governments support in Congress, where the presidents party lost its 68-year majority in the lower chamber. Now none of the 3 major political parties had an absolute majority. In this fragmented political environment the unilateral top-down approach was seen as

What has worked?

The subnational Doing Business reports, by providing a fact-based set of indicators that capture differences in local regulation and local implementation of national laws, prompted rst dialogue and then action on regulatory reform. Along the way they have also led to the sharing of experience, to competition and to collaboration, all of which have helped to promote and sustain change.

ECONOMY CASE STUDIES: MEXICO

33

one-stop shop that centralizes procedures and provides advice to entrepreneurs.

collaboration through Cofemer helped expand the system to more municipalities across more states. Today the system has been implemented in 186 municipalities across 30 states.6 According to a recent study, the SARE initiative has had a signicant impact.7 After the introduction of SAREs one-stop shops, the number of registered businesses increased by 5% and wage employment by 2.2%. After a few years of steady improvement at the state and municipal levels, the Office of the President saw a need for broad regulatory reforms at the federal level. One impetus was a perception that the subnational reform efforts needed another boost. Mexico Citys poor performance in the subnational rankings on the ease of doing business pushed the federal government to collaborate more closely with Mexico Citys 16 boroughs to coordinate reform efforts. A second impetus was Mexicos performance in the global rankings. While several regulatory reform programs had been introduced at the federal level in 200509, these had not been enough to propel Mexico into the ranks of the best performerssuch as New Zealand, Korea and Denmark, which were then among the top 35 on the ease of doing business. In September 2009 the Office of the President announced its intention to transform Mexicos regulatory environment. The aims were to build a regulatory framework centered on and involving the citizen, to increase competitiveness and to promote development. The Mexican government secured technical assistance from the World Bank Group to identify opportunities for regulatory reform and to provide expert advice. The initiative has already produced results in business registration. Previously there had been little coordination between federal agencies and the state and municipal organizations involved in the process. Now an online one-stop shop, Tuempresa, launched in August 2009, coordinates the federal procedures and is adding state and municipal procedures.8 Public notaries have been granted access. Today the online system processes about 100 new business registrations a month in Mexico City, or 7% of the

total. Mexico has also improved construction permitting, by merging and streamlining procedures related to zoning and utilities. More areas are being worked on. Reforms continue in trade, construction permitting, and business, property and collateral registration.

Creating competition

Competition between states was the biggest catalyst for reform. Faced by almost identical federal regulations, mayors and governors had difficulty explaining why it took longer or cost more to start a business or register property in their city or state. States that did poorly could not justify their poor performance, and they were inspired by the reform efforts of other states. This showed up in an accelerating pace of change. Doing Business in Mexico 2007 reported that 9 of 12 states (75%) had implemented reforms in at least one area measured by the report. Two years later, Doing Business in Mexico 2009 reported that 28 of 31 states (90%) as well as Mexico City had implemented Doing Business reforms. Mexican states were improving their regulatory environments, and the impulse for regulatory reform persisted even through changes in government. The pace of reform was maintained thanks in part to the regulatory reform units that states were beginning to create. Puebla set up the rst, in 2003. By 2005, 5 states had regulatory reform units. Today about 20 states do. Nuevo Len created the most recent one, in 2010. All the units have been created at the states initiative, with technical assistance from the federal government through Cofemer.

Seeing results

There are encouraging signs that strengthening different areas of the business environment at the same time produces better overall results for business creation. A study performed after the introduction of SARE in several states found that the program had a signicantly greater effect on the number of new businesses created in areas with a better overall investment climate.9 Changes are also apparent for rms. The share of senior managements time spent dealing with requirements imposed by government regulations fell from 20% in 2005 to 14% in 2009. During the same period the share of businesses that had applied for an operating license increased from 4% to 23%.10

Conclusion

Regulatory reform in Mexico has become an ongoing process. The government has taken steps to continue the subnational Doing Business project. In a rst for such projects, the methodology is being transferred to a reputable, independent think tank in Mexico, which expects to continue to do the study every 23 years. The federal and state governments have taken the lead on the funding side as well. The rst Doing Business in Mexico reports were nanced in part by donors (such as USAID) and the World Bank Group and in part by the Mexican government. The fourth is being fully funded by the federal and state nance ministries. The hope is that by tracking progress over time, continued periodic benchmarking by an independent third party will create incentives to maintain the reform effort through changes in government. The Doing Business in Mexico reports, capturing the progress of regulatory reform over time, show that it was not a one-time initiativebut instead an effort that has strengthened with continued benchmarking.

Promoting collaboration

Delegating the reform agenda to local authorities proved to be an essential part of the national reform effort. This fostered commitment, a sense of collaboration and better communication among federal, state and municipal authorities. Early on in the reform process the federal government collaborated with the states to improve business registration through the Rapid Business Opening System (SARE). A system of one-stop shops for local procedures, SARE was created to coordinate municipal procedures so that low-risk companies could get their license and start operating in a few days. The improved

34

DOING BUSINESS 2012

NOTES

1. Garca Villarreal 2010. Information on the

number of municipalities is from National Institute for Federalism and Municipal Development (INAFED), Los ltimos municipios creados, http://www.e-local .gob.mx/.

2. Population in 1985 from World Bank 2010b. 3. Cordova and Haddou-Ruiz 2008. 4. World Bank 2006a. 5. World Bank 2008a. 6. Information provided by Cofemer. 7. Bruhn 2011. 8. http://tuempresa.gob.mx. 9. Kaplan, Piedra and Seira 2007. 10. World Bank Enterprise Surveys (http://www

.enterprisesurveys.org).

You might also like

- Study Guide - Mere ChristianityDocument6 pagesStudy Guide - Mere ChristianityMichael Green100% (2)

- Mystery of The Dropa DiscsDocument18 pagesMystery of The Dropa DiscsMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Business Plan Template (ZAR)Document25 pagesBusiness Plan Template (ZAR)Nelce MiramonteNo ratings yet

- The Federal Budget Process, 2E: A Description of the Federal and Congressional Budget Processes, Including TimelinesFrom EverandThe Federal Budget Process, 2E: A Description of the Federal and Congressional Budget Processes, Including TimelinesNo ratings yet

- The What, The Why, The How: Mergers and AcquisitionsFrom EverandThe What, The Why, The How: Mergers and AcquisitionsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- l1 2024 Fixed IncomeDocument540 pagesl1 2024 Fixed IncomeAlex SalazarNo ratings yet

- The Pre-Adamic Catastrophe & Its AftermathDocument84 pagesThe Pre-Adamic Catastrophe & Its AftermathMichael Green100% (2)

- UPSC Civil Services Exam SyllabusDocument231 pagesUPSC Civil Services Exam SyllabusVarsha V. RajNo ratings yet

- Practical Innovation in Government: How Front-Line Leaders Are Transforming Public-Sector OrganizationsFrom EverandPractical Innovation in Government: How Front-Line Leaders Are Transforming Public-Sector OrganizationsNo ratings yet

- Abuse in International TaxationDocument4 pagesAbuse in International TaxationAmarendraKumarNo ratings yet

- SEBI Functions and Role in Regulating Indian Securities MarketDocument21 pagesSEBI Functions and Role in Regulating Indian Securities Marketkusum kalani100% (1)

- Accounting-Academic Journal Guide 2021Document5 pagesAccounting-Academic Journal Guide 2021lwidyawati_1No ratings yet

- Procurement and Supply Chain Management: Emerging Concepts, Strategies and ChallengesFrom EverandProcurement and Supply Chain Management: Emerging Concepts, Strategies and ChallengesNo ratings yet

- Review Fee Pauline ChristologyDocument6 pagesReview Fee Pauline ChristologyMichael Green100% (1)

- Summary The Role of Law in Business DevelopmentDocument4 pagesSummary The Role of Law in Business DevelopmentFatimah AzzahrahNo ratings yet

- Tax Invoice Trucks and BuyersDocument2 pagesTax Invoice Trucks and BuyersSyam JamiNo ratings yet

- Fortalezas Mexico IngDocument13 pagesFortalezas Mexico IngHno MayenNo ratings yet

- Public Sector Reform in New Zealand and Its Relevance To Developing CountriesDocument19 pagesPublic Sector Reform in New Zealand and Its Relevance To Developing Countriesfathurrozi.wali.zulkarnain-2020No ratings yet

- Taxation and Real Estate Development in Keas Zawang Plateau StateDocument48 pagesTaxation and Real Estate Development in Keas Zawang Plateau StateChigozieNo ratings yet

- Tax Evasion and Financial Market Participation in Brazilian FirmsDocument14 pagesTax Evasion and Financial Market Participation in Brazilian FirmsCorina-maria DincăNo ratings yet

- Poli Econ EssayDocument8 pagesPoli Econ EssayhelmasryNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Global Business Today Canadian 4th Edition Hill Solutions Manual PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Global Business Today Canadian 4th Edition Hill Solutions Manual PDFarianazaria0d9gsk100% (9)

- The Economics of The Informal SectorDocument16 pagesThe Economics of The Informal SectorAlexander Mori EslavaNo ratings yet

- Reflection 3 - Campos, Grace R.Document4 pagesReflection 3 - Campos, Grace R.Grace Revilla CamposNo ratings yet

- Contracting Task Force Report 0Document23 pagesContracting Task Force Report 0teetoszNo ratings yet

- w058 PDFDocument31 pagesw058 PDFSherwin OrdinariaNo ratings yet

- Government ReinventionDocument15 pagesGovernment ReinventionSopnil AbdullahNo ratings yet

- OCDE Recommendations For Sustainable DevelopmentDocument41 pagesOCDE Recommendations For Sustainable DevelopmentVivi BarqueroNo ratings yet

- Answer For Final Assessment Pad320 - Muhammad Athif Wajdi Bin Mohd Rizal - N4am1105kDocument7 pagesAnswer For Final Assessment Pad320 - Muhammad Athif Wajdi Bin Mohd Rizal - N4am1105kMUHAMMAD ATHIF WAJDI MOHD RIZALNo ratings yet

- Econ SG Chap16Document16 pagesEcon SG Chap16Mohamed MadyNo ratings yet

- Improving Real Property Tax Collection in MagsaysayDocument30 pagesImproving Real Property Tax Collection in MagsaysayErica Marie H FabrigasNo ratings yet

- Enterprising States 2011Document135 pagesEnterprising States 2011U.S. Chamber of CommerceNo ratings yet

- Regional Economic Growth in Mexico: Policy Research Working Paper 5369Document24 pagesRegional Economic Growth in Mexico: Policy Research Working Paper 5369Faca CórdobaNo ratings yet

- Crowley Tax Reform Case Studies v1Document37 pagesCrowley Tax Reform Case Studies v1MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Jobs and Economy - Real Solutions New Jobs - Roadmap To Florida's Future - Parts I and IIDocument20 pagesJobs and Economy - Real Solutions New Jobs - Roadmap To Florida's Future - Parts I and IIBill McCollumNo ratings yet

- Cut, Balance, and GrowDocument24 pagesCut, Balance, and GrowTeamRickPerryNo ratings yet

- Public Sector Reform MauritiusDocument2 pagesPublic Sector Reform MauritiusDeva ArmoogumNo ratings yet

- Enterprising States 2012 WebDocument90 pagesEnterprising States 2012 WebDavid LombardoNo ratings yet

- Ethics in TaxationDocument6 pagesEthics in Taxationchippanavin1No ratings yet

- How Federalism Will Help Improve Philippine EconomyDocument9 pagesHow Federalism Will Help Improve Philippine EconomyBoy GadorNo ratings yet

- Government_Accountability_and_Voluntary_Tax_CompliDocument10 pagesGovernment_Accountability_and_Voluntary_Tax_ComplipaulevbadeeseosaNo ratings yet

- Brooking Paper Owens&HamiltonDocument37 pagesBrooking Paper Owens&HamiltonStuart HamiltonNo ratings yet

- PWC. Paying Taxes 2012Document318 pagesPWC. Paying Taxes 2012Carlos Santillán DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Business Power and Tax Reform: Taxing Income and Profits in Chile and ArgentinaDocument36 pagesBusiness Power and Tax Reform: Taxing Income and Profits in Chile and ArgentinaandreaNo ratings yet

- DB11 Sub PhilippinesDocument175 pagesDB11 Sub PhilippinesRadvilė SmalinskaitėNo ratings yet

- Tyranny of The Status Quo - The Challenges of Reforming The Indian Tax SystemDocument56 pagesTyranny of The Status Quo - The Challenges of Reforming The Indian Tax SystemAditya SeethaNo ratings yet

- Accenture High Performance Government Executive Summary State and LocalDocument8 pagesAccenture High Performance Government Executive Summary State and LocalBrian MeshkinNo ratings yet

- Defining Local Economic Development and Why is it ImportantDocument14 pagesDefining Local Economic Development and Why is it Importantjessa mae zerdaNo ratings yet

- Tax Expenditures in Latin America Civil Society Perspective English Ibp 2019Document27 pagesTax Expenditures in Latin America Civil Society Perspective English Ibp 2019Paolo de RenzioNo ratings yet

- Commentary Governing To Deliver: Three Keys For Reinventing Government in Latin America and The CaribbeanDocument9 pagesCommentary Governing To Deliver: Three Keys For Reinventing Government in Latin America and The CaribbeanNo SeiNo ratings yet

- How To Address Regional and Sector-Specific Regulatory Issues? Case Study On MozambiqueDocument21 pagesHow To Address Regional and Sector-Specific Regulatory Issues? Case Study On MozambiqueaswardiNo ratings yet

- Department of Commerce: A Study On Us Corporate Taxation Adopted by Grant Thornton LLPDocument6 pagesDepartment of Commerce: A Study On Us Corporate Taxation Adopted by Grant Thornton LLPAnish PoojaryNo ratings yet

- Tax System Reform in Ethiopian Revenue ADocument5 pagesTax System Reform in Ethiopian Revenue AGoogle jkNo ratings yet

- Assessing Public Sector GovernanceDocument8 pagesAssessing Public Sector Governancealsaban_7No ratings yet

- A Jobs Recovery: Congressman Chuck Fleischmann's Jobs Plan For AmericaDocument22 pagesA Jobs Recovery: Congressman Chuck Fleischmann's Jobs Plan For AmericaRepChuckNo ratings yet

- Privatisation in Developing Countries (Performance and Ownership Effects)Document34 pagesPrivatisation in Developing Countries (Performance and Ownership Effects)Hanan RadityaNo ratings yet

- NPM, BPR, RegoDocument7 pagesNPM, BPR, Regolight&soundNo ratings yet

- Role of Government in Corporate GovernanceDocument2 pagesRole of Government in Corporate GovernanceIshanDograNo ratings yet

- CHAN, James L. Government Accounting - An Assessment of Theory, Purposes and StandardsDocument9 pagesCHAN, James L. Government Accounting - An Assessment of Theory, Purposes and StandardsHeloisaBianquiniNo ratings yet

- Rakoto Harimino Oliorilanto Contingency Factors Affecting The Adoption of Accrual Accounting in Malagasy Municipalities WWW Icgfm OrgDocument14 pagesRakoto Harimino Oliorilanto Contingency Factors Affecting The Adoption of Accrual Accounting in Malagasy Municipalities WWW Icgfm OrgFreeBalanceGRP100% (1)

- Turbotax Contact Number (1-828-668-2992)Document64 pagesTurbotax Contact Number (1-828-668-2992)PC FixNo ratings yet

- Vietnam governance reforms supported by donorsDocument9 pagesVietnam governance reforms supported by donorslhphuong03_728503220No ratings yet

- PPI - Workforce Investment ActDocument20 pagesPPI - Workforce Investment ActppiarchiveNo ratings yet

- Consumer, Government and Taxation ImpactDocument28 pagesConsumer, Government and Taxation ImpactREGLOS, Marie Nhelle K.No ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Implementation of Performance Contract Initiative at Municipal Council of Maua-KenyaDocument17 pagesFactors Affecting Implementation of Performance Contract Initiative at Municipal Council of Maua-KenyaKiran SoniNo ratings yet

- Independent Democratic Conference Regulation ReportDocument44 pagesIndependent Democratic Conference Regulation Reportrobertharding22No ratings yet

- Neolms Week 1-2,2Document21 pagesNeolms Week 1-2,2Kimberly Quin CanasNo ratings yet

- Government Accounting: An Assessment of Theory, Purposes and StandardsDocument12 pagesGovernment Accounting: An Assessment of Theory, Purposes and StandardsAl-Wahfi Suhada SipahutarNo ratings yet

- Notes: The Public Sector Governance Reform Cycle: Available Diagnostic ToolsDocument8 pagesNotes: The Public Sector Governance Reform Cycle: Available Diagnostic ToolsrussoNo ratings yet

- Mysteries of The MenorahDocument10 pagesMysteries of The MenorahMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- The Two ResurrectionsDocument7 pagesThe Two ResurrectionsMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Zorin BaikalDocument3 pagesZorin BaikalMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Life in The Third ReichDocument31 pagesLife in The Third ReichMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Sister Charlotte - A Nun S TestimonyDocument42 pagesSister Charlotte - A Nun S TestimonyTina Chauppetta Plessala100% (1)

- NSEL FiascoDocument7 pagesNSEL FiascoMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- The Scientific Case Against EvolutionDocument61 pagesThe Scientific Case Against EvolutionMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Technology & Innovation in The IDFDocument3 pagesTechnology & Innovation in The IDFMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- The Perfect Harmony of The NumbersDocument92 pagesThe Perfect Harmony of The NumbersMichael Green0% (1)

- The Big Questions Buzzing Over Boston Bombers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Have A Single AnswerDocument3 pagesThe Big Questions Buzzing Over Boston Bombers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Have A Single AnswerMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- The Firing Incident at BetuniaDocument5 pagesThe Firing Incident at BetuniaMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- AsianDevelopmentBankreport Asia 2050Document145 pagesAsianDevelopmentBankreport Asia 2050Michael GreenNo ratings yet

- Anti Semitic Disease PaulJohnsonDocument6 pagesAnti Semitic Disease PaulJohnsonMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Bible Authority Can Be ProvenDocument22 pagesBible Authority Can Be ProvenMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Tiananmen Incident of 1989Document10 pagesTiananmen Incident of 1989Michael Green100% (1)

- Obama Embraces and Works With Major Muslim Jihadist Leader and International Drug TraffickerDocument33 pagesObama Embraces and Works With Major Muslim Jihadist Leader and International Drug TraffickerMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- HAARP To Be Officially Offline From June 2014Document6 pagesHAARP To Be Officially Offline From June 2014Michael GreenNo ratings yet

- Pol Sci IiDocument8 pagesPol Sci IiParas MehendirattaNo ratings yet

- 20 Pictures of A Lion, A Bear and A TigerDocument10 pages20 Pictures of A Lion, A Bear and A TigerMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- Continuous Jewish Presence in The Holy LandDocument13 pagesContinuous Jewish Presence in The Holy LandMichael Green100% (1)

- 38 Reasons We Love IDFDocument17 pages38 Reasons We Love IDFMichael GreenNo ratings yet

- 7 Reasons Why Have Jews Rejected Jesus For Over 2Document32 pages7 Reasons Why Have Jews Rejected Jesus For Over 2Michael GreenNo ratings yet

- Pol Sci IDocument8 pagesPol Sci IAnusha ShettyNo ratings yet

- BA Political ScienceDocument9 pagesBA Political SciencePuspesh GiriNo ratings yet

- Management IIDocument16 pagesManagement IIMAX PAYNENo ratings yet

- Kelgaon Working Estimate 03.2.22Document457 pagesKelgaon Working Estimate 03.2.22ASHOK ARJUNRAO TAYADENo ratings yet

- Withdraw Funds ScriptDocument4 pagesWithdraw Funds ScriptЕвгений ТолстойNo ratings yet

- Where Nike Shoes Are Made & Globalization ImpactsDocument12 pagesWhere Nike Shoes Are Made & Globalization Impactshunter johnsonNo ratings yet

- Application of Differentiation To EconomicsDocument6 pagesApplication of Differentiation To Economicsvaibhavarora273No ratings yet

- Design and Evaluation of Electrical Services For An Energy Efficient Home - 1701825Document8 pagesDesign and Evaluation of Electrical Services For An Energy Efficient Home - 1701825Engr. Najeem Olawale AdelakunNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Foreign Currency TransactionsDocument10 pagesChapter 6 Foreign Currency Transactionsfitsum tesfayeNo ratings yet

- ABM11 - Business Mathematics - Q1 - W7 - (7) FINALDocument5 pagesABM11 - Business Mathematics - Q1 - W7 - (7) FINALEmmanuel Villeja LaysonNo ratings yet

- 2 Assingment of ASCDocument4 pages2 Assingment of ASCIram Zulfiqar Ali FastNUNo ratings yet

- Hacienda de CalambaDocument4 pagesHacienda de CalambaMary Jane MasulaNo ratings yet

- 1679028135898fw3TuyP3VyjUHvFh PDFDocument4 pages1679028135898fw3TuyP3VyjUHvFh PDFSV FilmsNo ratings yet

- A222 BWBB3193 Topic 03 ALMDocument70 pagesA222 BWBB3193 Topic 03 ALMNurFazalina AkbarNo ratings yet

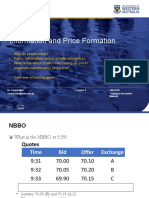

- Information and Price FormationDocument36 pagesInformation and Price FormationDylan AdrianNo ratings yet

- Cryptocurrency - Tips & Strategies For Your Investing Success by Dexter SanchezDocument75 pagesCryptocurrency - Tips & Strategies For Your Investing Success by Dexter SanchezgfgfgfgNo ratings yet

- InstaSummary Report of Vivid Global Industries Limited - 28-07-2020Document13 pagesInstaSummary Report of Vivid Global Industries Limited - 28-07-2020RajiNo ratings yet

- IFA CMA Exam Question Solutions on Non-Current LiabilitiesDocument15 pagesIFA CMA Exam Question Solutions on Non-Current LiabilitiesKamrul HassanNo ratings yet

- Summer 2023 BUS530 Course OutlineDocument6 pagesSummer 2023 BUS530 Course OutlinesayidNo ratings yet

- Case - International AcquisitionDocument6 pagesCase - International AcquisitionMayankJhaNo ratings yet

- The Firm and Its EnvironmentDocument80 pagesThe Firm and Its EnvironmentKarl EthanNo ratings yet

- Measurement Form of An T.W.Partition: Name of Work: FURNITUREDocument4 pagesMeasurement Form of An T.W.Partition: Name of Work: FURNITUREakshay salviNo ratings yet

- The Need For Financial Literacy Education For University Students in IndonesiaDocument5 pagesThe Need For Financial Literacy Education For University Students in IndonesiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Applied Economics 2Document8 pagesApplied Economics 2Sayra HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Marshall Plan for Africa Would Not WorkDocument2 pagesMarshall Plan for Africa Would Not WorkSari Yahya0% (1)

- OrdonioKara SocialChangeDocument4 pagesOrdonioKara SocialChangeJayson DoctorNo ratings yet

- China Three Red LinesDocument7 pagesChina Three Red LinesTrung Kiên Nguyễn ĐìnhNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Earnings Management To Issuance of Audit Qualification Evidence From IndonesiaDocument29 pagesThe Effect of Earnings Management To Issuance of Audit Qualification Evidence From IndonesiaMega LestariNo ratings yet