Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ep 058491

Uploaded by

Jom JeanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ep 058491

Uploaded by

Jom JeanCopyright:

Available Formats

Evolutionary Psychology

www.epjournal.net 2007. 5(1): 84-91

Original Article

Evolutionary Theorys Increasing Role in Personality and Social Psychology

Gregory D. Webster, Department of Psychology, University of Colorado at Boulder. Webster is now at Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA. Email: webster3@uiuc.edu.

Abstract: Has the emergence of evolutionary psychology had an increasing impact on personality and social psychological research published over the past two decades? If so, is its growing influence substantially different from that of other emerging psychological areas? These questions were addressed in the present study by conducting a content analysis of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (JPSP) from 1985 to 2004 using the PsycINFO online abstract database. Specifically, keyword searches for evol* or Darwin* revealed that the percentage of JPSP articles drawing on evolutionary theory was modest, but increased significantly between 1985 and 2004. To compare the growing impact of evolutionary psychology with other psychological areas, similar keywords searches were performed in JPSP for emotion and motivation, judgment and decision making, neuroscience and psychophysiology, stereotyping and prejudice, and terror management theory. The increase in evolutionary theory in JPSP over time was practically equal to the mean increase over time for the other five areas. Thus, evolutionary psychology has played an increasing role in shaping personality and social psychological research over the past 20 years, and is growing at a rate consistent with other emerging psychological areas. Keywords: evolutionary psychology, personality, social psychology, publication trends, history and systems of psychology, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Introduction Although evolutionary psychology may be considered either a theoretical perspective or a sub-discipline of psychology (Cornwell, Palmer, Guinther, and Davis, 2005), it is nevertheless an emerging area that is growing in influence. In their recent article, Cornwell et al. showed that introductory psychology textbooks have given increasing coverage to sociobiology, evolutionary psychology, or both, over the past 30 years (1975-2004). Although the tone of this increasing coverage became increasingly positive (or at least less negative) over time, some inaccurate interpretations of

Evolutionary Theory in Personality and Social Psychology

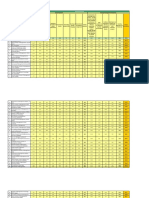

evolutionary psychology still persist. Cornwell et al. acknowledged that much more work is needed to evaluate fully how sociobiology or evolutionary psychology is being integrated within the social sciences (p. 371). To this end, the purpose of the present study was to empirically evaluate the extent to which evolutionary theory has impacted articles published in the flagship journal (the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology or JPSP) of a specific sub-discipline of psychology (social-personality psychology) over the past 20 years (1985-2004). Method PsycINFO keyword searches were performed using evolutionary psychology terms (evol* or Darwin*) for articles published in JPSP from 1985 to 2004. For comparison purposes, similar keyword searches were also performed for five other topics areas in social-personality psychology: (a) emotion and motivation (emot* or motiv*), (b) judgment and decision making (judgment* or decision*), (c) neuroscience and psychophysiology (neur*, physiologic*, or psychophysio*, but not neurotic*), (d) stereotyping and prejudice (stereotyp* or prejudic*), and (e) terror management theory (terror management or mortality salience). Articles published in an October 2003 special section of JPSP on social neuroscience were not counted toward the neuroscience and psychophysiology totals. These topic areas do not represent mutually exclusive categories. For example, a JPSP article on the evolutionary psychology of terror management theory would have counted toward both relevant topic areas. The five additional topic areas represent a broad convenience sample of many possible topic areas in social-personality psychology. Because evolutionary psychology can be viewed as a psychological sub-discipline or a unique theoretical approach (Cornwell et al., 2005), both psychological (stereotyping and prejudice) and interdisciplinary (emotion and emotion, judgment and decision making) sub-disciplines were chosen, as well as both methodological (neuroscience and psychophysiology) and theoretical (terror management theory) perspectives that have recently influenced social-personality psychology. The dependent variable was the proportion of the topic area articles out of the total number of JPSP articles per year. Since these proportions exhibited some year-to-year volatility, a three-year moving average was used to smooth short-term fluctuations in the data. Because proportion data often violate the homogeneity-of-variance assumption of regression (Judd and McClelland, 1989, pp. 525-526), an arcsine transformation was applied to the three-year moving average proportions: sin1(proportion1/2). Although all analyses were performed using the arcsine transformation, the data presented in Figure 1 show the raw three-year moving average percentages. The independent variable was publication year in JPSP. For each topic area, simple linear regressions were performed predicting change in the transformed moving average proportions over time. Results See Table 1 and Figure 1 for results. Significant linear increases in JPSP articles over time were detected for (a) evolutionary psychology, (b) emotion and motivation, (c) stereotyping and prejudice, and (d) terror management theory. In contrast, significant linear

Evolutionary Psychology ISSN 1474-7049 Volume 5(1). 2007.

-85-

Evolutionary Theory in Personality and Social Psychology

decreases in JPSP articles over time were detected for (a) judgment and decision-making and (b) neuroscience and psychophysiology. The mean of the six topic areas change-over-time slopes (M = 0.0019) did not differ significantly from zero (t5 = 0.96, p = .38). Moreover, none of the topic areas individual slopes differed significantly from the mean slope of the other five areas. Interestingly, the slope for evolutionary psychology was the same as the mean slope of the other five topic areas (both Ms = 0.0019). Although comparing the temporal slopes of these topic areas may be elucidating, it should be done with caution. First, each of these topic areas began to emerge at a different time. Thus, it may be difficult to compare an emerging topic area like evolutionary psychology with more established ones like emotion and motivation or stereotyping and prejudice. Second, only the linear effects of time were tested. It is certainly possible that different topic areas may grow or decline at differing curvilinear rates over time in JPSP. For example, some topic areas may have thresholds or tipping points after which they rapidly gain (or lose) acceptance. Further, emerging scientific fields often undergo growth spurts following identification (e.g., formal conferences) and institutionalization (e.g. establishing a dedicated journal or program of study; Feist, 2006). While interesting, the present data cannot speak to these possibilities. Table 1. Linear regression results: Proportion (arcsine of three-year moving average) of JPSP articles as a function of publication year (1985-2004) for six topic areas Topic area Evolutionary psychology Emotion and motivation Judgment and decision making Neuroscience and psychophysiology Stereotyping and prejudice Terror management theory *p .05. Discussion Consistent with previous research that has shown evolutionary psychologys increasing role in introductory psychology textbooks (Cornwell et al., 2005), the present research showed that evolutionary theory has been making substantial inroads into socialpersonality psychology by publishing empirical articles in its flagship journal, JPSP. Although the proportion of evolutionary psychology articles published in JPSP was modest, it increased at a rate similar to other topic areas in social-personality psychology. b 0.0019 0.0022 0.0026 0.0046 0.0077 0.0070 t16 2.11* 2.11* 2.17* 4.75* 10.72* 6.99* R2 .22 .22 .23 .58 .88 .75

Evolutionary Psychology ISSN 1474-7049 Volume 5(1). 2007.

-86-

Evolutionary Theory in Personality and Social Psychology

Figure 1. Percentage (three-year moving average) of JPSP articles as a function of publication year (1985-2004) for six topic areas (bs represent raw regression slopes)

Evolutionary Psychology 2 b = 0.035

Emotion & Motivation 40 b = 0.21 35

30

0 1985

1995 Publication Year

2005

25 1985

1995 Publication Year

2005

Judgments & Decisions 20 5

Neuroscience

b = -0.14

15 b = -0.19 10 1985

1995 Publication Year

2005

1 1985

1995 Publication Year

2005

Stereotyping & Prejudice 11 b = 0.39 2

Terror Management

b = 0.099 1

3 1985

1995 Publication Year

2005

0 1985

1995 Publication Year

2005

Evolutionary Psychology ISSN 1474-7049 Volume 5(1). 2007.

-87-

Evolutionary Theory in Personality and Social Psychology

Although the results were straightforward, they were not without their limitations. First, there was some overlap in the areas examined, since the categories were not mutually exclusive. For example, an article on evolutionary perspectives of emotion using psychophysiological methods would have counted toward three of the six topic areas. Second, popular topic areas in psychology, and perhaps social psychology in particular, may wax and wane with historical changes in the socio-political zeitgeist or funding changes in various research paradigms (Gergen, 1973). Thus, the linear trends observed here may only represent 20-year snapshots of long-term cyclical trends. Third, since 1986, JPSPs page layout and the number of pages it publishes each year has been relatively constant, which suggests that the percentage of journal space allocated to various topic areas may resemble a zero-sum game. For example, evolutionary psychology may have gained ground at the expense of one or more topic areas or theoretical approaches; however, it is also possible that, because of its interdisciplinary nature, evolutionary psychology has occasionally overlapped with other established areas (e.g., evolutionary approaches to emotion and motivation), which would obfuscate the necessity of a zero-sum scenario. Occasionally, specialized journals that cater to a specific topic area are established that may attract manuscripts that would have originally considered JPSP as an outlet. For example, the journal Neuropsychology, which began publishing in 1987, may have contributed to the observed decline in social neuroscience articles published in JPSP. Fourth, it is also possible that evolutionary psychologys increasing influence in JPSP is not due solely to growing acceptance, but rather to a combination of both growing acceptance and increasing criticism; however, JPSP rarely publishes comments and rejoinders that could artificially inflate a sub-disciplines influence based solely on its controversial nature. How should these results be interpreted within the larger context of ongoing publication trends in social-personality psychology, evolutionary psychology, and psychology in general? First of all, the present findings should only be generalized to articles published in JPSP, the flagship journal of social-personality psychology; however, it is unlikely that the observed trends would differ markedly for similar high-impact socialpersonality journals (e.g., Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin or PSPB). The extent to which evolutionary psychologys growing influence in social-personality psychology may generalize to other psychological sub-disciplines (e.g., clinical, cognitive, developmental, neuropsychology) is beyond the scope of the present study. Other research on social-personality publication trends in leading journals such as JPSP (Reis and Stiller, 1992; Webster, Bryan, Haerle, and OGara, 2005) and PSPB (Sherman, Buddie, Dragan, End, and Finney, 1999) have shown that articles have become longer, have included more authors and studies, and have employed more complex data analytic techniques over time. Similar trends have been observed in evolutionary psychologys flagship journal, Evolution and Human Behavior, such that the numbers of authors and studies have increased, as have the proportion of empirical (vs. theoretical or review) articles (Webster, 2007). Psychology articles in general have seen (a) an explosion in cited references (vs. other scientific disciplines, Adair and Vohra, 2003), (b) an increase in cognitive psychology and a decrease in behavioral psychology (Robins, Gosling, and Craik, 1999), and (c) an increase in article length that has leveled-off since the turn of the century (Webster, in press). Thus, for better or worse, as evolutionary theorys impact on

Evolutionary Psychology ISSN 1474-7049 Volume 5(1). 2007.

-88-

Evolutionary Theory in Personality and Social Psychology

social-personality psychology continues to grow, evolutionary psychologists can expect to read, write, and review longer articles with more studies using more empirical methods and increasingly sophisticated analyses. On a related note, evolutionary and social-personality psychology have witnessed a fruitful cross-fertilization over recent years. Perhaps most notably, evolutionary psychology has received attention in both the leading personality (Buss, 1999) and social (Buss and Kenrick, 1998) psychology handbooks. Similarly, the first comprehensive evolutionary psychology handbook has included chapters on evolutionary personality psychology (Figueredo et al., 2005) and evolutionary social psychology (Kenrick, Maner, and Li, 2005). Moreover, two pioneering edited volumes have been dedicated to the intersections of evolutionary and social psychology (Schaller, Simpson, and Gangestad, 2006; Simpson and Kenrick, 1997). Thus, evolutionary and social-personality psychology appear to have engaged in beneficial interweaving of mutual theoretical influence. What are the implications of these findings for the future of evolutionary psychology in the context of social-personality psychology? First, the results suggest that evolutionary theory has established a viable beachhead on the theoretical landscape of social-personality psychology, and successfully planted its flag in the sub-disciplines flagship journal, JPSP. Second, evolutionary psychologys growing influence in JPSP articles appears to mirror the growth rates of other, similar topic areas, on average. Third, as evolutionary psychological research becomes more empirical (Webster, 2007), it is more likely to gain widespread acceptance in sub-disciplines such as social-personality psychology, which has itself become more empirical by adopting more complex statistical techniques (Reis and Stiller, 1992). Whereas social-personality psychology has witnessed an increase in sophisticated research methods (Reis and Stiller, 1992), evolutionary psychology is only just beginning to carve out its own niche of scientific methods (Simpson and Campbell, 2005), which will require continued development and refinement if evolutionary psychology is to flourish as an empirical science in the future. Finally, although it is beyond the scope of the present findings, it is possible that the evolution of scientific theory may itself mimic Darwinian selection pressures, as various scientific theories merge or compete with one another over time. Moreover, the pursuit of science may itself be a signaling display of intelligence and creativity for the mating market, just as creating art and music appear to be (Miller, 1998). In addition, science and math may represent co-opted by-products of evolved adaptations (Feist, 2006, p. 217), such that they do not typically promote reproductive fitness directly, but may do so indirectly, through their signaling intelligence to potential mates, or their contributions to human society, or both. Although the present research cannot speak to these broader implications (e.g., it is unlikely to impact the authors fitness), it does provide an initial, empirical snapshot of the emerging scientific symbiosis between evolutionary psychology and social-personality psychology. Acknowledgements: This research was presented as a poster at the 4th Evolutionary Psychology Preconference at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Palm Springs, California, January 2006. This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under Training Grant Award PHS 2 T32 MH014257 entitled Quantitative Methods for Behavioral Research (to M. Regenwetter, principal

Evolutionary Psychology ISSN 1474-7049 Volume 5(1). 2007.

-89-

Evolutionary Theory in Personality and Social Psychology

investigator). This research was completed while the author was a postdoctoral trainee in the Quantitative Methods Program of the Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institute of Mental Health. Received 14 November 2006; revision received 10 January 2007; accepted 10 January 2007 References Adair, J. G., and Vohra, N. (2003). The explosion of knowledge, references, and citations: Psychologys unique response to a crisis. American Psychologist, 58, 15-23. Buss, D. M. (1999). Human nature and individual differences: The evolution of human personality. In L. A. Pervin and O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (2nd ed., pp. 31-56). New York: Guilford Press. Buss, D. M., and Kenrick, D. T. (1998). Evolutionary social psychology. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (4th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 982-1026). New York: McGraw-Hill. Cornwell, R. E. Palmer, C., Guinther, P. M., and Hasker, P. D. (2005). Introductory psychology texts as a view of sociobiology/evolutionary psychologys role in psychology. Evolutionary Psychology, 3, 355-374. Feist, G. J. (2006). The Psychology of Science and the Origins of the Scientific Mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Figueredo, A. J., Sefcek, J. A. Vasquez, G., Brumbach, B. H., King, J. E., and Jacobs, W. J. (2005). Evolutionary personality psychology. In D. M Buss (Ed.), The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (pp. 851-877). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Gergen, K. J. (1973). Social psychology as history. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 26, 309-320. Judd, C. M., and McClelland, G. H. (1989). Data Analysis: A Model-Comparison Approach. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Kenrick, D. T., Maner, J. K., and Li, N. P. (2005). Evolutionary social psychology. In D. M Buss (Ed.), The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (pp. 803-827) Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Miller, G. F. (1998). How mate choice shaped human nature: A review of sexual selection and human evolution. In C. Crawford and D. Krebs (Eds.), Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (pp. 87-129). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Reis, H. T., and Stiller, J. (1992). Publication trends in JPSP: A three-decade review. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 465-472. Robins, R. W., Gosling, S. D., and Craik, K. H. (1999). An empirical analysis of trends in psychology. American Psychologist, 54, 117-128. Schaller, M., Simpson, J. A., and Kenrick, D. T. (Eds.). (2006). Evolution and Social Psychology. New York: Psychology Press.

Evolutionary Psychology ISSN 1474-7049 Volume 5(1). 2007.

-90-

Evolutionary Theory in Personality and Social Psychology

Sherman, R. C., Buddie, A. M., Dragan, K. L., End, C. M., and Finney, L. J. (1999). Twenty years of PSPB: Trends in content, design, and analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 177-187. Simpson, J. A., and Campbell, L. (2005). Methods of evolutionary sciences. In D. M Buss (Ed.), The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (pp. 119-144). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Simpson, J. A., and Kenrick, D. T. (Eds.). (1997). Evolutionary Social Psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Webster, G. D. (2007). Increasing impact, diversity, and empiricism: The Evolution of Evolution and Human Behavior, 1980-2004. Manuscript submitted for publication. Webster, G. D. (in press). The demise of the increasingly protracted APA journal article? American Psychologist. Webster, G. D., Bryan, A., Haerle, D., and OGara, A. (2005, January). Increasing complexity in social and personality psychology articles: Publication trends in JPSP, 1986-2002. Poster presented at the 6th annual meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, New Orleans, LA.

Evolutionary Psychology ISSN 1474-7049 Volume 5(1). 2007.

-91-

You might also like

- Schroots-1996-Theoretical Developments in The Psychology of AgingDocument7 pagesSchroots-1996-Theoretical Developments in The Psychology of AginggabrielcastroxNo ratings yet

- Richard Michael Furr - Psychometrics - An Introduction-SAGE Publications, Inc (2021) - 39-50Document12 pagesRichard Michael Furr - Psychometrics - An Introduction-SAGE Publications, Inc (2021) - 39-50Hania laksmi /XI MIA 3 / 15No ratings yet

- Desarrollo y PsicoanalisisDocument36 pagesDesarrollo y PsicoanalisisArieles1984No ratings yet

- s11205-005-3516-0Document19 pagess11205-005-3516-0Sandra CorbovaNo ratings yet

- Dolan 2007 Do We Know What Make Us HappyDocument29 pagesDolan 2007 Do We Know What Make Us HappyDamian Vázquez GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Applying Social Psychology to Organizational ResearchDocument4 pagesApplying Social Psychology to Organizational ResearchJuan Manuel Caballero JaqueNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Psychology - Psychology - Oxford BibliographiesDocument20 pagesEvolutionary Psychology - Psychology - Oxford BibliographiesErick Antonio Bravo ManuelNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Psychology and PsychopathologyDocument9 pagesEvolutionary Psychology and PsychopathologyLuis Felipe Varela EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Gamble, Moreau, Tippett, Addis (2018) - Specificity of Future Thinking in Depression - A Meta-Analysis - PreprintDocument39 pagesGamble, Moreau, Tippett, Addis (2018) - Specificity of Future Thinking in Depression - A Meta-Analysis - PreprintMekhla PandeyNo ratings yet

- Work Psychology1 Sabah 3 2007Document23 pagesWork Psychology1 Sabah 3 2007Asadulla KhanNo ratings yet

- Work Psychology1 Sabah 3 2007Document23 pagesWork Psychology1 Sabah 3 2007Buy SellNo ratings yet

- WORK PSYCHOLOGY IN NATIONAL BANK OF OMANDocument19 pagesWORK PSYCHOLOGY IN NATIONAL BANK OF OMANAsadulla KhanNo ratings yet

- Do We Really Know What Makes Us Happy - A Review of The Economic Literature On The Factors Associated With Subjective Well-BeingDocument29 pagesDo We Really Know What Makes Us Happy - A Review of The Economic Literature On The Factors Associated With Subjective Well-BeingInna RamadaniaNo ratings yet

- Sociotropy, Autonomy, and Self-CriticismDocument10 pagesSociotropy, Autonomy, and Self-Criticismowilm892973100% (1)

- The Critique of PsychologyDocument246 pagesThe Critique of PsychologyFrederick Leonard83% (6)

- Emotional Intelli Ence: An Integral Part of Positive PsychologyDocument9 pagesEmotional Intelli Ence: An Integral Part of Positive PsychologyadrianitanNo ratings yet

- Elliot 2015 Color and Psychological FunctioningDocument8 pagesElliot 2015 Color and Psychological FunctioningKamran HughesNo ratings yet

- Baltes - 1987 - Theoretical Propositions of Life-Span Developmental Psychology On The Dynamics Between Growth and DeclineDocument16 pagesBaltes - 1987 - Theoretical Propositions of Life-Span Developmental Psychology On The Dynamics Between Growth and DeclineBruno PontualNo ratings yet

- Personality Theories For The 21st Century Teaching of Psychology 2011 McCrae 209 14Document7 pagesPersonality Theories For The 21st Century Teaching of Psychology 2011 McCrae 209 14HaysiFantayzee100% (2)

- Theoretical Communities and Theory: & Psychology: A Decade ReviewDocument9 pagesTheoretical Communities and Theory: & Psychology: A Decade ReviewMalahat HajiyevaNo ratings yet

- BlattDocument12 pagesBlattupanddownfileNo ratings yet

- LilienfeldDocument16 pagesLilienfeldFer VasNo ratings yet

- Personality Traits and Anxiety SymptomsDocument19 pagesPersonality Traits and Anxiety SymptomsSusana Díaz100% (1)

- Psy6 - Psychology and Social IssuesDocument22 pagesPsy6 - Psychology and Social Issuesrabarber1900No ratings yet

- Theory in Religion and AgingDocument21 pagesTheory in Religion and AgingNurmalaNo ratings yet

- Psihobiologia PersonalitatiiDocument6 pagesPsihobiologia PersonalitatiiDav Ina100% (1)

- Paul Baltes Lifespan (ENG)Document16 pagesPaul Baltes Lifespan (ENG)albitaalejandraNo ratings yet

- Kopala Sibley2019Document17 pagesKopala Sibley2019Ogi NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Child Temperament Review PDFDocument31 pagesChild Temperament Review PDFMamalikou MariaNo ratings yet

- What Is Extraversion For - 2012 McCabe 1498 505Document9 pagesWhat Is Extraversion For - 2012 McCabe 1498 505Iona KalosNo ratings yet

- Child Temperament ReviewDocument31 pagesChild Temperament ReviewMamalikou Maria100% (1)

- Jasp PreprintDocument46 pagesJasp PreprintNabeel NastechNo ratings yet

- Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination 3Document26 pagesPrejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination 3Veronica TosteNo ratings yet

- Falk & Heine (2015) - What Is Implicit Self-Esteem, and Does It Vary Across Cultures?Document22 pagesFalk & Heine (2015) - What Is Implicit Self-Esteem, and Does It Vary Across Cultures?RB.ARGNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence An Integral Part of PositivDocument10 pagesEmotional Intelligence An Integral Part of PositivbangNo ratings yet

- 2014 Book TheCatalyzingMind PDFDocument307 pages2014 Book TheCatalyzingMind PDFCatalina Henríquez100% (1)

- Textbook Geriatric Psychiatry 09 PDFDocument23 pagesTextbook Geriatric Psychiatry 09 PDFLydia AmaliaNo ratings yet

- A Psychology of Human Strengths Fundamental Questions and Future Directions For A Positive PsychologyDocument325 pagesA Psychology of Human Strengths Fundamental Questions and Future Directions For A Positive PsychologyAndreea Pîntia100% (14)

- Psychoanalytic Theory As A Unifying Framework For 21ST Century Personality AssessmentDocument20 pagesPsychoanalytic Theory As A Unifying Framework For 21ST Century Personality AssessmentPaola Martinez Manriquez100% (1)

- Publication Trends in Individual DSM Personality Disorders: 1971-2015Document23 pagesPublication Trends in Individual DSM Personality Disorders: 1971-2015mrt jchavarriaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Foundations of AttitudesFrom EverandPsychological Foundations of AttitudesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Steel Et Al., 2008Document70 pagesSteel Et Al., 2008giuliaNo ratings yet

- Diw sp0455Document30 pagesDiw sp0455generico2551No ratings yet

- Psychological Behaviorism Theory of Bipolar DisorderDocument26 pagesPsychological Behaviorism Theory of Bipolar DisorderLouise MountjoyNo ratings yet

- The Future of Positive Psychology: A Declaration of IndependenceDocument17 pagesThe Future of Positive Psychology: A Declaration of IndependenceEbonnie DiazNo ratings yet

- Personality and Motivational Systems in Mental RetardationDocument341 pagesPersonality and Motivational Systems in Mental RetardationLyz LizNo ratings yet

- Adult Personality Development (2001)Document6 pagesAdult Personality Development (2001)Kesavan ManmathanNo ratings yet

- 1989 VallerandOConnor CPDocument13 pages1989 VallerandOConnor CPNurul pattyNo ratings yet

- Retrieved From HTTPDocument31 pagesRetrieved From HTTPmeeno123No ratings yet

- SyllabusPSY4005 2014Document3 pagesSyllabusPSY4005 2014Ria BagourdiNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence in Social Phobia and Other Anxiety DisordersDocument11 pagesEmotional Intelligence in Social Phobia and Other Anxiety DisordersTracy Rebbun CrossleyNo ratings yet

- The Measurement of Self-Esteem in P&SP PreprintDocument54 pagesThe Measurement of Self-Esteem in P&SP PreprintMerlymooyNo ratings yet

- Kazdin+Wicked ProblemsDocument18 pagesKazdin+Wicked Problemsjenna ibanezNo ratings yet

- Four Meanings of Introversion Social Thi PDFDocument15 pagesFour Meanings of Introversion Social Thi PDFPetrNo ratings yet

- Russian and Soviet Psychology in the Changing Political Environment: A Time Series Analysis ApproachFrom EverandRussian and Soviet Psychology in the Changing Political Environment: A Time Series Analysis ApproachNo ratings yet

- What Emotions Really Are: The Problem of Psychological CategoriesFrom EverandWhat Emotions Really Are: The Problem of Psychological CategoriesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- WWW Thehindubusinessline Com Portfolio Big Story Big Story WDocument9 pagesWWW Thehindubusinessline Com Portfolio Big Story Big Story WJom JeanNo ratings yet

- SEBI issues regulatory framework for Online Bond Platform ProvidersDocument9 pagesSEBI issues regulatory framework for Online Bond Platform ProvidersJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Media Briefing Document - Business Standard For GoldenPiDocument4 pagesMedia Briefing Document - Business Standard For GoldenPiJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Kraction Films-Profile - Jan 2016 - JOMDocument13 pagesKraction Films-Profile - Jan 2016 - JOMJom JeanNo ratings yet

- REI - 2014 Brochure 2014Document16 pagesREI - 2014 Brochure 2014Akhil ParameswaranNo ratings yet

- Improving internal communication at STATECDocument24 pagesImproving internal communication at STATECJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Being in A Beginning or Early Stage Incipient: 2. Imperfectly Formed or Developed Disordered or IncoherentDocument14 pagesBeing in A Beginning or Early Stage Incipient: 2. Imperfectly Formed or Developed Disordered or IncoherentJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Objective Parametres Future OrientationDocument9 pagesObjective Parametres Future OrientationJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Global WarmingDocument2 pagesGlobal WarmingJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Property Insight q4Document46 pagesProperty Insight q4Jom JeanNo ratings yet

- Indian Real Estate Opening Doors PDFDocument18 pagesIndian Real Estate Opening Doors PDFkoolyogesh1No ratings yet

- Stress at WorkDocument94 pagesStress at WorktiggertenfourNo ratings yet

- A Good Speech: Writing For CeosDocument5 pagesA Good Speech: Writing For CeosJom JeanNo ratings yet

- SZ Social Media Marketing e BookDocument171 pagesSZ Social Media Marketing e BookAlexia IonNo ratings yet

- Stress & Stress Management PDFDocument30 pagesStress & Stress Management PDFAngie EspesoNo ratings yet

- Anselm ADocument7 pagesAnselm AJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Branding in The Post-Digital World 080612 PDFDocument19 pagesBranding in The Post-Digital World 080612 PDFChristina HoldenNo ratings yet

- Ethics of LibertyDocument336 pagesEthics of LibertyJMehrman33No ratings yet

- God GoodDocument7 pagesGod GoodJom JeanNo ratings yet

- A Good Speech: Writing For CeosDocument5 pagesA Good Speech: Writing For CeosJom JeanNo ratings yet

- MorrisseyDocument21 pagesMorrisseyJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Psychology Today - Steven Reiss - Secrets of HappinessDocument5 pagesPsychology Today - Steven Reiss - Secrets of HappinessJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Ipa 3Document8 pagesIpa 3Cristina ToaderNo ratings yet

- Meta I 1 2009 BocanceaDocument26 pagesMeta I 1 2009 BocanceaJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Aspers Patrik Phenomenology04Document15 pagesAspers Patrik Phenomenology04Jom JeanNo ratings yet

- Haslanger, Sally - Changing The Ideology and Culture of Philosophy Not by Reason (Alone) PDFDocument15 pagesHaslanger, Sally - Changing The Ideology and Culture of Philosophy Not by Reason (Alone) PDFDavid Robledo SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Liu Matthews 2005Document14 pagesLiu Matthews 2005Jom JeanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To PhilosophyDocument30 pagesIntroduction To PhilosophyStefan SnellNo ratings yet

- NosDocument16 pagesNosJom JeanNo ratings yet

- Asserting The Definition of PersonalityDocument4 pagesAsserting The Definition of Personalityalborada1000No ratings yet