Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ST Nicolas Cabasilas On The Mother of God

Uploaded by

akimelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ST Nicolas Cabasilas On The Mother of God

Uploaded by

akimelCopyright:

Available Formats

Beyond all holiness: St Nicolas Cabasilas on The Mother of God

Metropolitan Kallistos of Diokleia

To the Pilgrimage to Our Lady of Walsingham, March 2007 Ecumenical Marian Pilgrimage Trust

She is the cause of all beauty and magnificence, and of everything that humankind honours with hymns. All praise is to be ascribed to her alone. Indeed, she has even to be regarded as the cause of our very existence as human beings. And not only that, but it is moreover because of the Blessed Virgin that heaven and earth, the sun and the whole universe, have come into existence and attained well-being ... Christ chose her to be his Mother not only because she is the best of mothers, but because she is, in an absolute sense, the best of all (III,2; II,8).1

Such are the striking words with which St Nicolas Cabasilas (1319/23 after 1397) expresses his profound sense of awe and wonder before the person of Mary the Mother of God. A lay theologian and diplomat, contemporary and friend of St Gregory Palamas, Cabasilas is chiefly remembered for his two writings on sacramental theology, Life in Christ and Commentary on the Divine Liturgy.2 But his three homilies in honour of the Holy Virgin also constitute a significant contribution to Orthodox religious thought. Indeed, by virtue of these homilies he may justly be regarded as one of the foremost Marian theologians in the Greek Patristic tradition, surpassed in importance perhaps only by St John of Damascus. Whereas in the Life in Christ and the Commentary Cabasilas adopts a relatively simple and straightforward style, his homilies are far more elaborate in their manner of writing and more rhetorical. Yet, although rhetorical, they are also genuinely theological, expressing a doctrinal standpoint that is balanced and carefully argued. Without attempting to be exhaustive, let us consider seven points in his teaching concerning the Theotokos. 1. Christology. Cabasilas two major works, the Life in Christ and the Commentary, are both strongly Christological in character. So also, albeit in a less obvious way, are his three homilies in honour of the Holy Virgin. This Christocentric perspective may be identified as a first and fundamental point in his Marian theology. When he glorifies Mary, this is never solely for and in herself. He views her not in isolation but always, either explicitly or implicitly, in terms of her relationship to Christ her Son. If she is highly praised, in words that may sometimes appear extravagant to a modern Western reader, this is specifically because she is Theotokos, Birthgiver of God. The Mother is honoured because of her Child. For Cabasilas she is first and foremost Hodigitria not that this actual term occurs in the three homilies the One who points towards Christ, who shows us the way and

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

leads us to him. She is, as he puts it, the path and door to the Saviour (III,13). Thus, when Cabasilas says somewhat surprisingly, in words already quoted, that heaven and earth, the sun and the whole universe, have come into existence because of Mary (III,2), he surely has in mind the Incarnation of Christ. If the human birth of the Divine Logos is the focal point of all history, the reason why the world was brought into existence if the Incarnation is, in the words of St Maximos the Confessor, the blessed end on account of which all things were created3 then it was Mary, as Christ's Mother, who acted as the human instrument through which that blessed end came to pass. In a relative sense, therefore, strictly under Christ and by virtue of her relationship to him, she too may be regarded as the reason why the universe exists. If we keep in mind this Christocentric perspective underlying the three Marian homilies of Cabasilas in their entirety, we can better understand certain passages in which he applies to Mary titles or phrases that normally would be applicable only to Christ. Thus he says of her, She became for us purification and propitiation, and has sanctified the whole human race, and she justified all of us (III, 6: cf. Heb. 1:3; Rom. 3:21 and 5: 18-19). ? is meaning, however, is clarified when immediately afterwards he goes on to describe Mary's sacrifice as a preparatory sacrifice of purification offered before the great sacrifice on behalf of all the human race. Marys sacrifice in this way has value and efficacy solely because it prepares the way for the great sacrifice presented by her Son. It is Christ, that is to say, who reconciles us to God through his Cross; but at the same time it was Mary his Mother who was the means whereby Christ our Saviour came to dwell among us. When, employing a phrase frequently found in Orthodox liturgical texts, Cabasilas styles Mary the salvation of humankind, this is to be understood in a similar manner. As Cabasilas himself expresses it, He [Christ] is the cause of my sanctification; but you [Mary] are the co-cause (III, 12). Here, without actually using the word, Cabasilas comes close to the Roman Catholic notion of Mary as Co-Redemptrix, who by virtue of her Divine Motherhood shares to a unique degree in Christ's work of redemption. There can, however, be no doubt that for Cabasilas Jesus Christ is indeed the one and only Redeemer of the world. He would have agreed with the words of Pope John XXIII, The Madonna is not pleased when she is put above her Son. 2. The link between the two Covenants. Another primary element in the Marian theology of Cabasilas is the way in which he regards the Blessed Virgin as the connecting link and the bond of union between the Old Testament and the New, who in her own person ensures the continuity of sacred history. She is, as he expresses it, at one and the same time both the fruit of the Law and the treasure -house of Grace (I, 3). She is the Daughter of Israel, summing up in he r own person all the sanctity of God's Chosen People under the Old Covenant, and at the same time she is Mother of Christ, through whom the New Covenant was brought to pass. Emphasizing her roots in Judaism, Cabasilas applies to the Virgin language taken from the Mosaic law: she is the true tabernacle of God, the ark and encampment of Moses, the holy of holies (I, 3; III, 2; I, 13).

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

3. Mary and the doctrine of the human person. Here we approach close to the heart of Cabasilas theology of the Virgi n Mary. As Panagiotis Nellas observes, his three homilies on the Mother of God could equally well be described as three Byzantine essays on anthropology.4 Martin Jugie rightly sums up the Cabasilan standpoint in the words: Mary is the ideal type of humanity; she alone has fully realized the divine idea of what it is to be human; she is the human being par excellence. 5 One recalls the aphorism of G.K.Chesterton: Men are men, but Man is a woman. To quote the words of Cabasilas himself:

She made manifest in this world human personhood in its purity and completeness, as it was in paradise: such, that is to say, as it was created in the beginning, such as it ought to have remained, and such as it may subsequently become through our struggle to recover our true nobility (I, 16).

Although Cabasilas, as we have noted, sees Mary as rooted in the Old Covenant, yet in this present context, when expounding her anthropological significance, he emphasizes a complementary aspect of her identity: her radical newness. As exemplar of human personhood, she represents in the history of the human race a new beginning, a fresh start, a clear and decisive inauguration. So, in his homily for the Nativity of the Theotokos, celebrated on 8 September, he describes the feast as the birthday not so much of the Virgin but rather of the whole inhabited earth (I, 18). Mary's birth is nothing less than the commencement of the new creation: The Virgin has fashioned a new heaven and a new earth (III, 4: cf. Isaiah 65:17; Revelation 21:1). With good reason she can be called The First Man, for (says Cabasilas), she first and alone showed forth human nature (I, 4). She reveals to us Man, disclosing what we were created to be (I, 6). In all this, Cabasilas viewpoint is clear and consistent. In Adams seed and progeny prior to the Virgin Mary, we see human nature marred by sin; in her for the first time we see our humanness undistorted and in its true integrity, according to the divine intention (I, 14). Here, as before, some readers of Cabasilas Marian homilies may begin to feel uneasy. Is he not assigning to the Holy Virgin what properly speaking should be ascribed only to her Son? Whereas for Cabasilas it is Mary's birth that constitutes the birthday of the whole inhabited earth, is not St Basil the Great more correct when he describes the Nativity of Christ, not that of Mary, as the birthday of the human race?6 For St Paul it is Christ who is the Second Adam (I Corinthians 15:45), embodying and expressing that fullness of our human personhood which the First Adam failed to attain. Is not Cabasilas treading upon dangerous ground when he terms Mary the First Man, apparently regarding her as not simply the New Eve but as herself the New Adam?7 Cabasilas has an answer here. He would not in any way deny that Christ is the New Adam. Yet in his opinion Christ does not reveal to us the meaning of our humanness in the way that Mary does; for he was God as well as man, whereas she was exclusively human. Christ, being God, could not have sinned; but Mary, being human, could have sinned, although in fact she did not. Christ did indeed take integral human nature, but in his case this human nature was united hypostatically to his divine nature. He is thus a divine hypostasis who has assumed into himself the plenitude of

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

what it is to be human. In Mary's case, however, that plenitude exists not in a divine but in a human hypostasis. The Second Adam, argues Cabasilas, by virtue of the fact that he is God by nature, could not reveal his second nature, that is, our [human] nature, in such a way that it was manifest on its own (I, 14). Yet this precisely is what Mary, by God's grace, was enabled to do. It is not difficult to appreciate the point that Cabasilas is here seeking to establish. Yet, on the principle already enunciated, Mary under Christ, it is legitimate to feel certain reservations. Would it not have been wiser for him to affirm that, in seeking to apprehend the true dimensions of our human personhood, we should look first and foremost at Christ the Theanthropos (God-man)? If we suggest that, because Christ is a divine hypostasis, he cannot reveal to us the authentic completeness of human nature, we are in danger of opening the door to Eutychian Docetism, although that was in no way Cabasilas' intention. Mary is certainly a mirror in which we humans see reflected our own true face. But our primary and ultimate looking-glass is always our Lord. Men are men, but Man is a woman: yes, indeed but The Man is Jesus Christ. The Christocentric stance of Cabasilas own Mariology requires us to say no less than that. Implicit in Cabasilas anthropological teaching concerning the Holy Virgin, there can be discerned what may broadly be termed a Scotist view of the Incarnation. For Cabasilas, as for St Maximus the Confessor and St Isaac the Syrian as, equally, for Cabasilas contemporaries St Gregory Palamas and Theophanes of Nicaea the determining motive for the Incarnation was not simply the fall. On the contrary, the human birth of the Logos was something willed by the Trinity from all eternity. The Incarnation, that is to say, is not to be seen merely as a contingency plan, devised because of human sin. As the supreme expression of the Creator's love for his creation, revealing the authentic dimensions of our personhood, it is part of God's primary plan for the world that he has made. In this way, Mary's vocation to be Mother of God incarnate is likewise an integral part of that primary plan. It is for this reason that Cabasilas can claim that the world was created for the Holy Virgin and because of her. Just as the tree exists because of the fruit, he argues, so it can be asserted that all creation came into being for her sake (III, 2); she is in this sense the fruit of all created things (III, 3). Here Cabasilas reaffirms the teaching of St Andrew of Crete, who describes Mary as the final and ultimate end of all creation, on account of whom the world came into being.8 From all ages, then, and not just subsequent to the fall of humankind into sin, God desired to create a Mother through whom the saving economy of the Incarnation might be realized. She is, as St Bernard says in the concluding Canto of Dantes Paradiso, termine fisso deterno consigl io, the fixed goal of the eternal counsel. 4. The co-operation of the Mother of God. In his interpretation of the anthropological significance of Mary, Cabasilas insists more particularly upon one specific way in which she reveals to us the essential meaning of our personhood; and that is through the exercise of her free will. Human freedom is a master-theme throughout the major works of Cabasilas. He is not a Pelagian or a semi-Pelagian, for he underlines the need for divine grace. But at the same time he is totally convinced that to be human is to

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

enjoy liberty of choice, and this centrality of freedom is to be seen preeminently in the life of the Mother of God. She was not simply a passive tool in God's hands but, to use the phrase of St Irenaeus, She co-operated with the economy.9 St Paul's words, We are co-operators with God (I Corinthians 3:9), apply first and foremost to her. As Cabasilas puts it, she acted as God's helper and co-operated with the Creator in the work of refashioning the creation (I, 17). When we seek to fathom the meaning of synergeia, of the mysterious interaction between God's grace and human freedom, we should look above all at Mary. The chief moment when the Theotokos exercised this co-operation through the employment of her human freedom was at the Annunciation, when she replied to Gabriel, Behold, the servant of the Lord; let it to be done to me according to your word (Luke 1:38). God did not simply announce the divine plan to her through the intermediary of the archangel, but he waited for her voluntary response. And this response was not merely a foregone conclusion; Mary was indeed chosen by God, but for her own part she also made a decisive act of free choice. In the epigrammatic phrase of Cabasilas, The Word of God is formed through the word of his Mother (II, 10). In a memorable passage, whose importance has been rightly emphasized by (among others) Vladimir Lossky and Paul Evdokimov, Cabasilas states:

The Incarnation of the Word was not only the work of the Father, of his Power [the Son], and of his Spirit the first consenting, the second descending, the third overshadowing but it was also the work of the will and the faith of the Virgin. Without the three divine persons this design could not have been set in motion; but likewise the plan could not have been carried into effect without the consent and faith of the all-pure Virgin. Only after teaching and persuading her does God make her his Mother and receive from her the flesh that she consciously wills to offer him. Just as he was conceived by his own free choice, so in the same way she became his Mother voluntarily and with her free consent (II, 4-5).

5. The sinlessness of Mary. In his treatment of the Virgin as a model for human personhood, Cabasilas draws attention not only to her freedom of choice but equally to her entire sinlessness. She is higher in sanctity than any other member of the human race, above and beyond all holiness.10 She alone, he writes, among all human beings, in every age from the beginning to the end, stood firm against all evil, and rendered back to God unimpaired the beauty conferred on us by him (I, 6). Not only did she keep her soul pure from every evil, but her sanctity extended from her soul to her body, so that even in this present life she possessed a spiritual body (I, 4; II, 2: cf. I Corinthians 15: 44). Even though some of the Holy Teachers state that [at the Annunciation] the Virgin was purified beforehand by the Spirit, writes Cabasilas, yet this does not signify that she was previously sinful; purification in this context merely indicates an addition of the gifts of grace (I, 10). She was first and uniquely detached from sin once for all (III, 8); in other words, totally pure and sinle ss from her birth. Cabasilas even asserts that she never in any way needed reconciliation (II, 3), which, taken out of context, could be interpreted to mean that she did not require to be saved by Christ, although this can hardly be what Cabasilas intends. The unambiguous testimony to the Virgins sinlessness, to be found throughout Cabasilas three Marian homilies, naturally raises the question:

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

Did he accept the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, as taught in the Roman Catholic Church? The Assumptionist Father Martin Jugie concludes confidently that he did,11 whereas the Greek theologian Panagiotis Nellas argues to the contrary.12 The standpoint of Nellas seems closer to the truth, for three reasons in particular: (i) There is lacking from Cabasilas, as from the Greek Patristic tradition in general, one of the central presuppositions of the Latin doctrine of the Immaculate Conception: the notion of inherited guilt. Contrary to the Latin doctrine, Cabasilas clearly maintains that Mary, while sinless in all her personal actions, nonetheless inherited fallen human nature: The spotless Virgin did not have heaven as her city, nor was she born from the bodies that are there, but she was born from the earth, in the same way as everyone else born from this fallen race that had grown ignorant of its own nature (I, 6). And Cabasilas continues, in words that leave no room for doubt: She did not receive a nature unacquainted with all wickedness; born as she was before the coming of Christ the New Man, she did not initially enjoy any exceptional grace or inclination derived specifically from his Incarnation. On the contrary, in common with the rest of the human race prior to the coming of Christ, she inherited a nature that had acquired the experience of being constantly defeated and a body that was enslaved to sin. Lacking as she did any distinctive or unique grace, such as was not available to all other human beings in the period between the fall and the coming of Christ, she simply used to the full the grace and power that were given also to the rest of humankind (I, 7). Her situation was essentially that of her fellow humans. To appreciate Cabasilas' position on this question, a firm distinction needs to be made between the levels of nature and of will. On the level of nature, Mary was subject to the consequences of the fall, but on the level of her will and of her personal exercise of voluntary choice she was altogether sinless. A further point, confirming that Cabasilas did not accept the notion of the Immaculate Conception, is his stress upon Mary as the link between the Old and the New Covenant (see 2 above). When the Roman Catholic definition of 1854 states that Mary was conceived immaculately intuitu meritorum Christi Iesu Salvatoris humani generis, having in view the merits of Christ Jesus the Saviour of the human race, it seems to remove the Holy Virgin from her position within the Old Covenant and to place her proleptically and by anticipation within the New; and in this way the cohesion and continuity of salvation history are impaired. Conscious as he is of the importance of this continuity, Cabasilas considers that at the Annunciation, when Mary responded, Behold the handmaid of the Lord, she was speaking not in her own name only but in the name of all the holy men and women of the Chosen People in the many generations before her. As Georges Florovsky rightly observes,

(ii)

(iii)

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

The Blessed Virgin was representative of the race, i.e. of the fallen human race, of the old Adam.13 The continui ty of sacred history, then, requires that Mary did not enjoy any special grace or inclination derived from the future Incarnation, and not available to the rest of fallen humankind (see point [ii] above). The pre -redemption ( praeredemptio), posited by the Latin doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, is therefore excluded by Cabasilas. The fact that the Holy Virgin inherited fallen human nature, and that as a link between the two Covenants she was, prior to the Annunciation, in the same position as the other righteous men and women of the Chosen People, does not in any way diminish her glory, but in Cabasilas eyes it renders her sinlessness all the more remarkable. Her holiness was not merely passive, the result of a special gift of grace from God, but it was also active, attained through her own zeal and strength (I, 14). Here, as always, Cabasilas highlights the crucial value of human freedom. Even though Cabasilas does not have the Latin teaching directly in view, yet in his exposition of the sinlessness of Mary he closely anticipates the modern Orthodox standpoint vis--vis the Roman Catholic dogma of the Immaculate Conception. 6. The final glory of the Theotokos. Although Cabasilas rejects the Immaculate Conception, yet as regards the Bodily Assumption he is in substantial agreement with the modern Roman Catholic view, even though he nowhere envisages the proclamation of this doctrine as a dogma of the Church. It is his belief that Mary underwent physical death, but that her body, after remaining for a little while in the tomb, was raised from the dead and re-united with her soul, so that she was then assumed, body and soul together, into heaven (III, 12). There are in fact a few Roman Catholics, such as Martin Jugie, who have adopted an immortalist view, arguing that the Virgin Mary in common with Enoch (Genesis 3: 24) and Elijah (2 Kings 2: 11) was received into glory without actually undergoing bodily death. Even if this notion is not specifically excluded by the Papal definition of 1950, I understand that it is not the normal opinion in the Latin West. So far as the Orthodox East is concerned, it is clearly affirmed in the liturgical texts, and more generally in the Greek Patristic tradition as a whole, that Mary actually experienced physical death, just as her Son had done; and Cabasilas himself is clear on this point. There is equally no trace in Cabasilas of the view, found in some Greek writers, that after her death Mary's body, although taken up from the tomb, was not at that point reunited with her soul, but was placed in paradise understood as a region distinct from heaven there to remain until the Parousia. This assumptionless opinion is held by, for example, the Emperor Leo the Wise and John Geometres in the tenth century, and by Joseph Bryennios in the fifteenth. Cabasilas, on the other hand, holds that even now Mary already dwells in the heavenly places with the full integrity of her personhood, body and soul together; and this is likewise the position of St John of Damascus and, in the later Byzantine period, of St Gregory Palamas and Saint Mark of Ephesus, as it is also of the contemporary Orthodox Church.14

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

The main argument that Cabasilas advances in support of the Bodily Assumption of the Virgin is that there exists between her life and that of Christ her Son a close configuration, a constant correspondence. Here he follows John of Damascus, who makes this the main theme in his homilies on the Dormition: as the Damascene puts it, There is nothing between Mother and Son.15 It was right, says Cabasilas, that she should participate with her Son in all the actions of his providence towards us. Thus, continues Cabasilas, she shared to the utmost in Christ's sufferings when she stood at the foot of the Cross, so fulfilling Symeon's prophecy, A sword will pierce through your own soul also (Luke 2:35). In this way, more than anyone else, she realized in her own person the meaning of Paul's words, I make up what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ (Colossians.1:24). Just as he underwent death, so also did she, being conformed to a death like his (Romans 6: 5; Philippians 3:10); like him, she descended into the depths of the earth; and finally before all others she shared also in his Resurrection, being taken up, body and soul together, into the heavenly places:

It was right that her all-holy soul should be separated from her most sacred body separated, and so united to the soul of her Son, the second light united to the first. Her body remained for a short time in the earth, and then departed thence to be together with her soul. For it was right that she should traverse all the paths which were trodden by the Saviour, that she should shine upon both the living and the dead, and so in every way should sanctify our human nature, before receiving as her dwelling-place the region appropriate to her. Thus the tomb received her body for a little while, and then heaven in its turn received this new earth, this spiritual body, this treasure of our life, more venerable than the angels, more holy than the archangels.... So the Tree was restored to the Fruit, and the Mother to her Son (III, 12).

Here Cabasilas applies to Mary's body, assumed into heaven, the phrase applied by St Paul to the resurrection of the body at the last day: It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body. (I Corinthians 15:44). By spiritual in this context Paul did not mean dematerialized but filled with the grace and power of the Holy Spirit. Cabasilas is to be understood in the same sense: Mary is present in heaven in her physical body, but this physical body has been divinized and glorified. The resurrection of the Blessed Virgin and her ascension with her body into heaven render her par excellence an eschatological p erson. The resurrection of the body, which awaits all of us at the Parousia, has in her case been anticipated and is already an accomplished fact. She has passed beyond death and judgement, and even now she dwells completely in the glory of the Age to come. Indeed, her entry into the Eschaton, realized in its plenitude at her Bodily Assumption, was already inaugurated during her life on earth. From the moment when the Spirit overshadowed her at the Annunciation, she began to possess a spiritual body. Even in this present life, affirms Cabasilas, she shared in the blessings that are to come and reigned in the Kingdom that is reserved for the righteous. While her absolute glorification was reserved to the period after her death, yet long before that she shared in glory, living to the full a hidden life in Christ (III, 10). Here significantly Cabasilas applies to Mary the phrase life in Christ that he adopted as the title of his best-known work. The Blessed Virgin Mary, more than any other human being, has expressed within herself that

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

grace-given state of transfiguration about which the Apostle spoke when he exclaimed: I live yet no longer I, but Christ lives in me (Galatians 2:20). It is this state of Christ living in me that was made supremely manifest at her Assumption. 7. The Virgin as intercessor. Although taken up into heaven, the Virgin still remains inseparably joined to us on earth through her ceaseless intercession on our behalf. This her ministry of prayer constitutes a seventh and final element in Cabasilas theology of the Theotokos. Before the coming of the Paraclete, she became our paraclete to God, he writes (II, 3). But if she prays for us, may we also sometimes pray for her? There is one notable occasion when it seems that we do so, in the Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, immediately after the Epiclesis of the Spirit upon the Holy Gifts. Here the celebrant says to God: Also we offer you this spiritual worship for those who have fallen asleep... above all for our all-holy, pure, most blessed and glorified Lady the Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary. Despite, however, what might seem to be the obvious meaning of this passage, Cabasilas insists at some length in his Commentary on the Divine Liturgy that this is not a prayer on her behalf but simply an expression of thanksgiving.16 We do not intercede for Mary; it is she who intercedes for us. Such, in its main outlines, is the complex and sensitive teaching of St Nicolas Cabasilas concerning the person and wor k of the Mother of God. Needless to say, his three Marian homilies do not claim to constitute a systematic treatise. They are sermons although it is unclear whether they were delivered before an actual congregation, or were simply literary exercises and, as sermons, their purpose is to awaken the prayer and devotion of the audience, rather than to develop a series of doctrinal theses in logical sequence. Nevertheless, the homilies are profoundly theological, and they contain all the essential elements for a proper appreciation of Mary's place in the scheme of salvation. The most valuable among these elements is surely Cabasilas understanding of the Theotokos as the supreme model of what it is to be a human being. So long as she is seen under Christ and in union with him, she can indeed be regarded as a true paradigm of the ultimate potentialities of our human personhood at its highest. And what she shows us about our humanness is above all, as Cabasilas eloquently proclaims, the cardinal value of freedom. In the words of Sren Kierkegaard, The most tremendous thing granted to human beings is choice, freedom. And if you desire to save that freedom and to preserve it, there is only one way: in the same second...to give it back to God, and yourself with it. That, as St Nicolas Cabasilas recognized, is exactly what the Holy Virgin did. Metropolitan Kallistos of Diokleia 2007

Metropolitan Kallistos

Beyond all holiness

Notes

1

The three Marian homilies of Cabasilas are cited by Roman numerals: I

( On the Nativity to the Mother of God); II (On the Annunciation); III (On the Dormition). This is then followed, in Arabic numerals, by the number of the relevant sub-section.

2

The Life in Christ, tr. Carmino J. deCatanzaro, with an introduction by

Boris Bobrinskoy (Crestwood: St Vladimirs Seminary Press, 1974.); A Commentary on the Divine Liturgy, tr. J. M. Hussey and P. A. McNulty, with an introduction by R. M. French (London: SPCK, 1960). So far as I know, the three Marian homilies have not been translated into English.

3 4 5

To Thalassios, Question 60 (ed. Laga and Steel, p. 75, lines 33-34). I Theomitor (Athens: Tinos Shrine of the Mother of God, 1968), p.9. Limmacule conception dans lEcriture sainte et dans la tradition orientale On the Nativity of Christ 6 (PG 31: 1473A); possibly not by Basil. In his three Marian homilies, Cabasilas in fact nowhere uses the title New Quoted in Nellas, I Theomitor, p. 170, note 12. Against the heresies III, 21, 7. Commentary on the Divine Liturgy 33:7. Limmacule conception, pp. 246-63. I Theomitor, pp. 48-49. The Ever-Virgin Mother of God, in Georges Florovsky, Creation and On the paradise theory and its opponents, see Kallistos Ware, The Final

(Rome: Academia Mariana, 1952), p.247.

6 7

Eve.

8 9

10 11 12 13

Redemption, Collected Works, vol. III (Belmont, MA: Nordland, 1976), p. 181.

14

Mystery: the Dormition of the Holy Virgin in Orthodox worship, in William M. McLoughlin and Jill Pinnock (ed.), Mary for Time and Eternity (Leominster: Gracewing, 2007), pp. 219-52.

15

On the Dormition III,5 (ed. Kotter, p. 554, line 23), Cf. Kallistos Ware, The

Earthly Heaven: The Mother of God in the Teaching of St John of Damascus, in William M. McLoughlin and Jill Pinnock (ed.), Mary for Earth and Heaven (Leominster: Gracewing, 2002), pp. 355-68, epecially pp. 363-4.

16

Commentary on the Divine Liturgy 49:12.

10

You might also like

- Saint Photius The Great - Mystagogy of The Holy SpiritDocument37 pagesSaint Photius The Great - Mystagogy of The Holy Spiritvictor_georgescu100% (3)

- Hieromonk Damascene - What Christ Accomplished On The CrossDocument22 pagesHieromonk Damascene - What Christ Accomplished On The CrossYamabushi100% (2)

- 00 Theosis and The Doctrine of SalvationDocument49 pages00 Theosis and The Doctrine of SalvationRonnie Bennett Aubrey-Bray100% (7)

- Divine Presence Cabasilas - PDFDocument243 pagesDivine Presence Cabasilas - PDFlpaguaga3932100% (4)

- THE HOLY FATHERS: A SURE GUIDE TO TRUE CHRISTIANITY. by Father Seraphim (Rose)Document8 pagesTHE HOLY FATHERS: A SURE GUIDE TO TRUE CHRISTIANITY. by Father Seraphim (Rose)Иоанн Дойг100% (6)

- Spiritual Maturity Through UnderstandingDocument21 pagesSpiritual Maturity Through UnderstandingmahannaNo ratings yet

- The Kontakia, Theology and Poetry in Early ByzantiumDocument250 pagesThe Kontakia, Theology and Poetry in Early ByzantiumWolfsbane Hobbes100% (2)

- 01 - Orthodox Dogmatic Theology IDocument454 pages01 - Orthodox Dogmatic Theology IRareș GoleaNo ratings yet

- Orthodox Handbook On Ecumenism-Watermarked PDFDocument998 pagesOrthodox Handbook On Ecumenism-Watermarked PDFLuke Lovejoy100% (1)

- Henri de Lubac and Radical OrthodoxyDocument30 pagesHenri de Lubac and Radical OrthodoxyakimelNo ratings yet

- God and FreedomDocument13 pagesGod and FreedomakimelNo ratings yet

- Ibn Arabī, Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya, and The Political Functions of Punishment in The Islamic HellDocument0 pagesIbn Arabī, Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya, and The Political Functions of Punishment in The Islamic HellakimelNo ratings yet

- Theosis and Gregory PalamasDocument24 pagesTheosis and Gregory PalamasMirceaNo ratings yet

- East & West - Fundamental Differences by Fr. John RomanidesDocument23 pagesEast & West - Fundamental Differences by Fr. John RomanideszyrasNo ratings yet

- Orthodox Advice On FastingDocument7 pagesOrthodox Advice On FastingKen Okoye100% (1)

- The Orthodox Church and Eschatological Frenzy: The Recent Proliferation of "Antichristology" and Its Perilous Side-EffectsDocument68 pagesThe Orthodox Church and Eschatological Frenzy: The Recent Proliferation of "Antichristology" and Its Perilous Side-EffectsHibernoSlavNo ratings yet

- Reading The Fathers TodayDocument12 pagesReading The Fathers TodayakimelNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Orthodox TheologiansDocument12 pagesContemporary Orthodox TheologiansStefan Soponaru100% (1)

- Liturgy of St. James (Eliz. English) - Byz. NotationDocument26 pagesLiturgy of St. James (Eliz. English) - Byz. NotationHieromonk EphraimNo ratings yet

- The BlessedDocument16 pagesThe BlessedGiorgosby17100% (1)

- The Problem of Hell: A Thomistic Critique of David Bentley Hart's Necessitarian UniversalilsmDocument21 pagesThe Problem of Hell: A Thomistic Critique of David Bentley Hart's Necessitarian UniversalilsmakimelNo ratings yet

- Homily On The Burial of ChristDocument20 pagesHomily On The Burial of ChristakimelNo ratings yet

- OROLO & W. D. GannDocument56 pagesOROLO & W. D. GannGaurav Garg100% (1)

- St. Ignatius Brianchaninov - Basics of Spiritual LifeDocument9 pagesSt. Ignatius Brianchaninov - Basics of Spiritual LifeHeiko Pufal100% (1)

- The Eucharistic Doctrine of The Byzantine IconoclastsDocument19 pagesThe Eucharistic Doctrine of The Byzantine IconoclastsakimelNo ratings yet

- How To Read Genesis - Hieromonk Seraphim RoseDocument25 pagesHow To Read Genesis - Hieromonk Seraphim Rosehexaimeron_ro100% (2)

- The Problem of The Desiderium Naturale in The Thomistic TraditionDocument10 pagesThe Problem of The Desiderium Naturale in The Thomistic TraditionakimelNo ratings yet

- The Sacrament of The Altar: To Save This Essay..Document1 pageThe Sacrament of The Altar: To Save This Essay..akimelNo ratings yet

- Analogia: The Pemptousia Journal for Theological Studies Vol 2 (St Maximus the Confessor)From EverandAnalogia: The Pemptousia Journal for Theological Studies Vol 2 (St Maximus the Confessor)No ratings yet

- The Salvation of The World According To ST SilouanDocument12 pagesThe Salvation of The World According To ST Silouanakimel100% (1)

- The True Believer by Aidan KavanaughDocument10 pagesThe True Believer by Aidan KavanaughakimelNo ratings yet

- Knowing The Purpose of Creation Through The ResurrectionDocument267 pagesKnowing The Purpose of Creation Through The ResurrectionΛευτέρης Κοκκίνης100% (1)

- Theosis (Eastern Orthodox Theology)Document7 pagesTheosis (Eastern Orthodox Theology)j.miguel593515No ratings yet

- G. Florovsky, Aspects of Church History (Collected Works, Vol. 4) (Nordland Publishing Company 1975)Document301 pagesG. Florovsky, Aspects of Church History (Collected Works, Vol. 4) (Nordland Publishing Company 1975)Adrian Cristi Adrian Cristi100% (3)

- The Hesychastic Controversy and its Impact on Orthodox and Catholic RelationsDocument34 pagesThe Hesychastic Controversy and its Impact on Orthodox and Catholic RelationscaralbertoNo ratings yet

- Jay Dyer Refutes Romanides On Analogia Entis and The LogoiDocument18 pagesJay Dyer Refutes Romanides On Analogia Entis and The Logoist iNo ratings yet

- There Is Nothing Untrue in The Protevangelion's Joyful, Inaccurate TalesDocument2 pagesThere Is Nothing Untrue in The Protevangelion's Joyful, Inaccurate Talesakimel100% (1)

- Patristic Theology and Post-Patristic Heresy SymposiumDocument206 pagesPatristic Theology and Post-Patristic Heresy SymposiumBranko Milosevic100% (3)

- The theology of the icon screen according to Symeon of ThessalonikeDocument22 pagesThe theology of the icon screen according to Symeon of ThessalonikeacapboscqNo ratings yet

- Louth Maximus EcclesiologyDocument14 pagesLouth Maximus Ecclesiologyic143constantin100% (1)

- Ramelli Reviews The Devil's Redemption by McClymondDocument10 pagesRamelli Reviews The Devil's Redemption by McClymondakimelNo ratings yet

- Ascetical Homilies Tableof Contents 1Document10 pagesAscetical Homilies Tableof Contents 1John MorcosNo ratings yet

- Apokatastasis in Gnostic Coptic TextsDocument14 pagesApokatastasis in Gnostic Coptic Textsakimel100% (1)

- 'But The Problem Remains': John Paul II and The Universalism of The Hope For SalvationDocument25 pages'But The Problem Remains': John Paul II and The Universalism of The Hope For SalvationakimelNo ratings yet

- 'But The Problem Remains': John Paul II and The Universalism of The Hope For SalvationDocument25 pages'But The Problem Remains': John Paul II and The Universalism of The Hope For SalvationakimelNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsDocument62 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and PoliticsTeds TV89% (84)

- These Truths We Hold - The Holy Orthodox Church: Her Life and TeachingDocument247 pagesThese Truths We Hold - The Holy Orthodox Church: Her Life and TeachingKelvin Wilson100% (6)

- The Human Person As An Icon of The TrinityDocument20 pagesThe Human Person As An Icon of The Trinityakimel100% (3)

- Original Sin According To Saint Paul - John RomanidesDocument21 pagesOriginal Sin According To Saint Paul - John Romanides09yak85No ratings yet

- Paul and UniversalismDocument15 pagesPaul and Universalismakimel100% (1)

- Fr. Anthony Alevizopoulos - Basic Dogmatic Teaching An Orthodox HandbookDocument189 pagesFr. Anthony Alevizopoulos - Basic Dogmatic Teaching An Orthodox HandbookDior100% (1)

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Light of The ScripturesDocument38 pagesEastern Orthodoxy in Light of The ScripturesJesus LivesNo ratings yet

- Staniloae Final DraftDocument35 pagesStaniloae Final DraftluciantimofteNo ratings yet

- Visual Catechism (Abridged)Document28 pagesVisual Catechism (Abridged)Michael E. Malulani K. Odegaard100% (2)

- Controversial End Time Prophecies by The Holy EldersDocument6 pagesControversial End Time Prophecies by The Holy EldersJohn Baptiste100% (3)

- Orthodoxy's Realism of Divine-Human CommunionDocument29 pagesOrthodoxy's Realism of Divine-Human CommunionAugustin FrancisNo ratings yet

- St. Justin Popovich - Orthodox Faith and Life in ChristDocument123 pagesSt. Justin Popovich - Orthodox Faith and Life in ChristDiorNo ratings yet

- OrthodoxDocument158 pagesOrthodoxLarry Day100% (2)

- Fr. George Metallinos - The Way An Introduction To The Orthodox FaithDocument114 pagesFr. George Metallinos - The Way An Introduction To The Orthodox FaithJustino Carneiro100% (4)

- The Natural Desire To See GodDocument21 pagesThe Natural Desire To See GodakimelNo ratings yet

- Preparing Children For The Sacrament of ConfessionDocument12 pagesPreparing Children For The Sacrament of ConfessionfabianNo ratings yet

- IEC-60721-3-3-2019 (Enviromental Conditions)Document12 pagesIEC-60721-3-3-2019 (Enviromental Conditions)Electrical DistributionNo ratings yet

- Fire of Purgation in Gregory of Nyssa by Armando ElkhouryDocument27 pagesFire of Purgation in Gregory of Nyssa by Armando ElkhouryakimelNo ratings yet

- Athanasius: Creation Ex-NihiloDocument15 pagesAthanasius: Creation Ex-NihiloDimmitri ChristouNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of Marketing Marketing ManagementDocument51 pagesNature and Scope of Marketing Marketing ManagementFeker H. MariamNo ratings yet

- Nicholas Healy - HENRI DE LUBAC ON NATURE AND GRACE: A NOTE ON SOME RECENT CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE DEBATEDocument30 pagesNicholas Healy - HENRI DE LUBAC ON NATURE AND GRACE: A NOTE ON SOME RECENT CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE DEBATEFrancisco J. Romero CarrasquilloNo ratings yet

- Perichoresis in Gregory and MaximusDocument21 pagesPerichoresis in Gregory and MaximusBaciu AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Nikolaos Loudovikos__Consubstantiality Beyond Perichoresis. Personal Threeness, Intra-divine Relations, And Personal Consubstantiality in Augustine's, Aquinas' and Maximus the Confessor's Trinitarian TheologiesDocument21 pagesNikolaos Loudovikos__Consubstantiality Beyond Perichoresis. Personal Threeness, Intra-divine Relations, And Personal Consubstantiality in Augustine's, Aquinas' and Maximus the Confessor's Trinitarian TheologiesAni LupascuNo ratings yet

- Akathist To St. Paisios The AthoniteDocument8 pagesAkathist To St. Paisios The AthoniteFra Petrus100% (1)

- Symeon of Thessaloniki and The Theology of The Icon ScreenDocument22 pagesSymeon of Thessaloniki and The Theology of The Icon Screenlimpdelicious100% (1)

- Saint Gregory Palamas, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies-The One Hundred and Fifty Chapters-Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (1988)Document295 pagesSaint Gregory Palamas, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies-The One Hundred and Fifty Chapters-Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (1988)nyomchen100% (15)

- The Way by Fr. George MetallinosDocument137 pagesThe Way by Fr. George Metallinosdelef367% (3)

- Fifth Ecumenical CouncilDocument5 pagesFifth Ecumenical CouncilakimelNo ratings yet

- Annihilation or Salvation? A Philosophical Case For Preferring Universalism To AnnihilationismDocument24 pagesAnnihilation or Salvation? A Philosophical Case For Preferring Universalism To AnnihilationismakimelNo ratings yet

- Eternally Choosing HellDocument18 pagesEternally Choosing Hellakimel100% (1)

- Trinity and Man Gregory of NyssaDocument249 pagesTrinity and Man Gregory of Nyssapezzilla100% (8)

- Heat and Light: David Bentley Hart On The Fires of HellDocument9 pagesHeat and Light: David Bentley Hart On The Fires of Hellakimel100% (1)

- Augustinianism and PredestinationDocument36 pagesAugustinianism and Predestinationakimel100% (1)

- The Patristic Heritage and Modenity PDFDocument21 pagesThe Patristic Heritage and Modenity PDFMarian TcaciucNo ratings yet

- The Rich Hues of Purple Murex DyeDocument44 pagesThe Rich Hues of Purple Murex DyeYiğit KılıçNo ratings yet

- The Redemption of Evolution: Maximus The Confessor, The Incarnation, and Modern ScienceDocument6 pagesThe Redemption of Evolution: Maximus The Confessor, The Incarnation, and Modern Scienceakimel100% (4)

- The Life in Christ by Nicholas CabasilasDocument19 pagesThe Life in Christ by Nicholas CabasilascatchcrabNo ratings yet

- Indian Institute OF Management, BangaloreDocument20 pagesIndian Institute OF Management, BangaloreGagandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Analogia: The Pemptousia Journal for Theological Studies Vol 9 (Ecclesial Dialogue: East and West I)From EverandAnalogia: The Pemptousia Journal for Theological Studies Vol 9 (Ecclesial Dialogue: East and West I)No ratings yet

- Peter Damian FILIOQUE Procession Greeks Latins CreedDocument1 pagePeter Damian FILIOQUE Procession Greeks Latins CreedPeter Brandt-SorheimNo ratings yet

- Church Book Triodion 2018 PDFDocument134 pagesChurch Book Triodion 2018 PDFFragile FuturesNo ratings yet

- Justification by FaithDocument7 pagesJustification by FaithakimelNo ratings yet

- Cunningham37 2Document12 pagesCunningham37 2markow2No ratings yet

- With No Qualifications: The Christological Maximalism of The Christian EastDocument7 pagesWith No Qualifications: The Christological Maximalism of The Christian EastakimelNo ratings yet

- Leaving The Womb of ChristDocument17 pagesLeaving The Womb of ChristakimelNo ratings yet

- Revering An Image of The Holy TrinityDocument3 pagesRevering An Image of The Holy TrinityakimelNo ratings yet

- Chetan Bhagat's "Half GirlfriendDocument4 pagesChetan Bhagat's "Half GirlfriendDR Sultan Ali AhmedNo ratings yet

- Body Scan AnalysisDocument9 pagesBody Scan AnalysisAmaury CosmeNo ratings yet

- City of Brescia - Map - WWW - Bresciatourism.itDocument1 pageCity of Brescia - Map - WWW - Bresciatourism.itBrescia TourismNo ratings yet

- LAC-Documentation-Tool Session 2Document4 pagesLAC-Documentation-Tool Session 2DenMark Tuazon-RañolaNo ratings yet

- Believer - Imagine Dragons - CIFRA CLUBDocument9 pagesBeliever - Imagine Dragons - CIFRA CLUBSilvio Augusto Comercial 01No ratings yet

- Voltaire's Candide and the Role of Free WillDocument3 pagesVoltaire's Candide and the Role of Free WillAngy ShoogzNo ratings yet

- VNC Function Operation InstructionDocument11 pagesVNC Function Operation InstructionArnaldo OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Donny UfoaksesDocument27 pagesDonny UfoaksesKang Bowo D'wizardNo ratings yet

- Java MCQ QuestionsDocument11 pagesJava MCQ QuestionsPineappleNo ratings yet

- 256267a1Document5,083 pages256267a1Елизавета ШепелеваNo ratings yet

- Maximizing modular learning opportunities through innovation and collaborationDocument2 pagesMaximizing modular learning opportunities through innovation and collaborationNIMFA SEPARANo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Ee3311.002.07f Taught by Gil Lee (Gslee)Document3 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Ee3311.002.07f Taught by Gil Lee (Gslee)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Osora Nzeribe ResumeDocument5 pagesOsora Nzeribe ResumeHARSHANo ratings yet

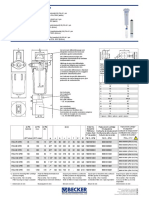

- Medical filter performance specificationsDocument1 pageMedical filter performance specificationsPT.Intidaya Dinamika SejatiNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Sciences P1 Nov 2015 Memo EngDocument9 pagesAgricultural Sciences P1 Nov 2015 Memo EngAbubakr IsmailNo ratings yet

- Brooks Instrument FlowmeterDocument8 pagesBrooks Instrument FlowmeterRicardo VillalongaNo ratings yet

- PM - Network Analysis CasesDocument20 pagesPM - Network Analysis CasesImransk401No ratings yet

- 01 Design of Flexible Pavement Using Coir GeotextilesDocument126 pages01 Design of Flexible Pavement Using Coir GeotextilesSreeja Sadanandan100% (1)

- Manual - Sentron Pac Profibus Do Modul - 2009 02 - en PDFDocument106 pagesManual - Sentron Pac Profibus Do Modul - 2009 02 - en PDFDante Renee Mendoza DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship Project-NishantDocument80 pagesSummer Internship Project-Nishantnishant singhNo ratings yet

- Policies and Regulations On EV Charging in India PPT KrishnaDocument9 pagesPolicies and Regulations On EV Charging in India PPT KrishnaSonal ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Exam Ref AZ 305 Designing Microsoft Azure Infrastructure Sol 2023Document285 pagesExam Ref AZ 305 Designing Microsoft Azure Infrastructure Sol 2023maniNo ratings yet

- Levels of Attainment.Document6 pagesLevels of Attainment.rajeshbarasaraNo ratings yet

- Addition and Subtraction of PolynomialsDocument8 pagesAddition and Subtraction of PolynomialsPearl AdamosNo ratings yet