Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Student Drinking Spring 2013: Figure 1. Students' Self-Reported Drinking Behavior

Uploaded by

Brian CottonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Student Drinking Spring 2013: Figure 1. Students' Self-Reported Drinking Behavior

Uploaded by

Brian CottonCopyright:

Available Formats

Student Drinking Spring 2013

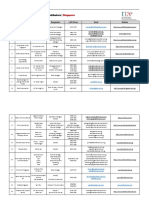

INTRODUCTION This survey, conducted by Student Affairs Research and Assessment, provides data on alcohol use and high-risk drinking behavior of undergraduate students at University Park. Survey questions focus on students' alcohol consumption, the direct and indirect consequences of that consumption, and protective and risk behaviors associated with drinking. While this topic has been assessed regularly since 1995, the survey was significantly revised in 2008 with the assistance of Dr. Rob Turrisi and staff in the Penn State Prevention Research Center and has been conducted annually since that year. Although some pre-2008 comparisons can be made, other findings are only comparable to data gathered since 2008. Primarily, 2011 data (the most recent prior administration) are presented in this report for comparison. Data from other years are available at http://studentaffairs.psu.edu/assessment/alphapulse.shtml. This survey was administered by email/web. At University Park, a random sample of 4,990 undergraduate students was invited to participate. In total, 1,174 students completed the survey for a 23.5% response rate. The confidence interval for the resulting sample is +/-2.86%. Of the respondents, 55.8% were female and 44.2% were male; 83.0% were 18 to 20 years old; and 57.4% lived off campus. Seventy-eight percent were White domestic students, 14.4% were domestic Students of Color, and 6.1% were international students (1.7% were of unknown race). For information on the Pulse methodology, please visit: http://studentaffairs.psu.edu/assessment/pulse. FINDINGS Alcohol Consumption Prevalence of Alcohol Use When asked how they would best describe their alcohol usage, the majority of students (68.7%) reported being either light or moderate drinkers (Figure 1).

Alcohol use and high-risk drinking behavior at University Park

Figure 1. Students' Self-Reported Drinking Behavior

2008 2011 2013

43.5% Students 32.1% 33.5% 23.3% 23.9% 17.7% 29.5%

38.7% 39.2%

6.7% 4.6% 7.5% Never tried or don't currently drink Light drinkers Moderate drinkers Heavy drinkers

Penn State Pulse is a project of Student Affairs Research and Assessment. For further information, please visit www.studentaffairs.psu.edu/assessment or contact Dr. Katherine Reed saraoffice@psu.edu, 222 Boucke, University Park, PA 16802, (814) 863-1809. U.Ed. STA 13-92

This publication is available in alternative media on request. Penn State is committed to affirmative action, equal opportunity, and the diversity of its workforce.

In addition, 57.0% indicated they had tried alcohol (more than a few sips) prior to the age of 18. While 20.1% reported they have never gotten drunk, 43.6% had gotten drunk for the first time prior to the age of 18. Quantity of Consumption Students were asked about their drinking behavior on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights of a typical week during this academic year. Roughly two-thirds of students reported drinking on Friday and Saturday nights of a typical week, whereas 13.5% reported drinking on Wednesday nights and 37.0% on Thursday nights (Table 1). The percentage of students who reported drinking on a given night was lower than it was in 2011 (Table 1). The average numbers of drinks per hour of students who drink on a given night was about the same as in 2011 and down slightly compared to 2008 (Figure 2). The Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) levels of students who drink were higher on the weekends at .09 on Friday and Saturday nights compared to .05 on Wednesday and .07 on Thursday evenings (Table 1). The BAC levels of students for each night in the 2013 administration were slightly higher than those of students in 2011 (Table 1). Table 1. Nightly Alcohol Use During a Typical Week % Who are Drinking Avg. # of Drinks Night 2011 2013 2011 2013 Wednesday 13.8 13.5 0.42 0.42 Thursday 39.6 37.0 1.69 1.64 Friday 69.6 66.3 3.86 3.76 Saturday 69.2 66.6 3.95 3.91

Avg. # of Hours 2011 2013 0.32 0.32 1.21 1.18 2.75 2.69 2.81 2.83

Avg. BAC* 2011 2013 0.042 0.045 0.064 0.069 0.083 0.088 0.085 0.090

* BAC is reported for drinkers only. All other data in this table represent all respondents.

Figure 2. Avg. Number of Drinks Per Hour (Drinkers only)

2008 Drinks per Hour 1.6 1.3 1.3 1.6 1.4 1.4 2011 2013 1.5 1.4 1.5 1.5 1.4 1.4

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Students were also asked how many times they got drunk during a typical month of the current academic year and of their senior year in high school (Figure 3). During the current academic year, 19.5% of students indicated they got drunk on 7 or more days during a typical month, whereas 29.1% indicated they dont drink or didnt get drunk. In comparison, 59.4% of students reported that they did not get drunk during a typical month of their senior year in high school and only 3.7% got drunk 7 or more days. Men, White students, students of legal drinking age, and off-campus students reported getting drunk significantly more frequently during a typical month of the current academic year than their respective counterparts (analysis not shown).

Figure 3. Number of Days Students Got Drunk During a Typical Month

59.4% Senior Year of High School Current Academic Year

Students

29.1% 23.1% 23.2% 14.7% 9.4% 4.4% 5 to 6 days 13.4% 3.7% 7 or more days 19.5%

Never/don't/didn't drink

1 to 2 days

3 to 4 days

Peak Drinking Behavior Students were asked to report on the occasion when they drank the most in the previous three months. On that occasion, students averaged 7.42 drinks over 3.89 hours. 63.7% of students who drink consumed two or less drinks per hour (Figure 4) during peak drinking occasions, with an overall average of 2.12 drinks per hour, compared to an average of 2.09 in 2011. Students, on average, reported drinking at this peak volume 2.84 times during the three-month period. Fortyeight percent reported drinking at a peak level 1 to 2 times; 15% said 3 to 4 times; and 16% said 5 or more times (with 22% reporting they didnt drink). While 22.4% of students who drink (compared to 27.0% in 2011) reported peak drinking behavior resulting in a BAC of .079 or lower (below the legal limit of .080), 22.8% indicated a BAC of .250 or higher (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Drinks Consumed per Hour During Peak Drinking (Drinkers Only)

2008 42.9% 42.9% 44.1% 2011 2013

Students

16.7%

21.3% 19.6%

25.0% 22.1%

20.1%

15.4%

13.7%

16.3%

>0 to 1 drinks

>1 to 2 drinks

> 2 to 3 drinks

> 3 drinks

Figure 5. Blood Alcohol Content of Drinkers During Peak Drinking Experience

22.8% 22.4%

A BAC of: .040 - .079 Can cause: Lower inhibition, minor reasoning impairment Impaired balance, speech, judgement, reasoning, reaction time Nausea, anxiety, disorientation, vomiting, memory loss Severe mental, physical sensory impairment, possible death

BAC .250 BAC: .160 - .249

25.7%

BAC: .079 BAC: .080 - .159

.080 - .159

.160 - .249

29.1%

.250

High-Risk Drinking High-risk, or binge drinking, is defined as having four or more drinks in a two-hour period for women and five or more drinks in a two-hour period for men. Frequent high-risk drinkers are those students who report having binged three or more times during a two-week period. Occasional high-risk drinkers are those who report having binged one or two times during a two-week period. Just under half of the respondents (43.9%) reported engaging in high-risk drinking behavior in the previous two weeks with 16.6% being classified as frequent high-risk drinkers (Figure 6). These data indicate a slight decline in high-risk drinking since 2008, when 52.8% of students reported engaging in this activity. Similar to previous years, men engaged in high-risk drinking at a greater rate than women (46.5% compared to 41.7% respectively), though the difference is not statistically significant (Figure 7). The 2008-13 high-risk drinking rates are lower than what had been reported in recent years (58.9% in 2006, 55.2% in 2004, and 60.4% in 2003). The question, however, was revised in 2008 which may account for the difference. Since 2008, the question has been based on the number of drinks consumed during a two -hour period as compared to in one sitting or in a row that had been asked in the previous years.

Figure 6. Number of Times Students Engaged in High-Risk Drinking During a Two-Week Period

56.2% 52.5% 47.2% Students 2008 2011 2013

28.7% 28.8% 27.3% 14.6% 12.6% 10.7%

9.4%

6.0% 5.9%

0/don't drink

1-2 times

3-4 times

5 or more times

Figure 7. Percentage of Male and Female Students Who Engage in High-Risk Drinking

Men 60.6% 54.0% 52.0% 52.6% 46.5% 41.7% 2009 2010 2011 2013 Women

59.0% Percent

48.1% 46.4% 2008

42.5%

As depicted in Figure 8, men and White students were more likely to report engaging in high-risk drinking behavior than their counterparts. Off-campus students were significantly more likely than on-campus students to report engaging in high-risk drinking. Evidence suggests a significant inverse relationship between high-risk drinking and GPA (Figure 8).

4

Figure 8. Percentage of High-Risk Drinkers within Groups

Men Women White students Students of Color Off-campus On-campus 21 & older Under 21 GPA < 3.00 GPA 3.00-3.29 GPA 3.30-3.59 GPA 3.60-4.00 46.5% 41.7% 47.1% 40.1% 47.2% 39.2% 54.5% 55.1% 49.2% 46.5% 41.0% 39.1%

Percent

Perceptions of Alcohol Use Students were asked how much alcohol they think a typical Penn State student of their same sex consumes on a typical Thursday, Friday, or Saturday evening. These perceptions of alcohol use are compared to the actual reported behavior for female and male students in Figure 9. As demonstrated, students perceive a higher quantity of alcohol consumed than what is actually reported, a trend that is consistent over time (data not shown). In addition, both women's and men's perceptions in 2013 are similar to previous years (data not shown).

Figure 9. Perceptions v. Reported Behavior by Gender: Avg Number of Drinks Consumed in a Typical Evening

Perception of others' drinking Own reported behavior

Men

Number of Drinks 6.8 4.6 3.8 2.0 6.9 4.8 3.2 1.3

Women

5.4 3.1

5.5 3.1

Thursday Consequences of Alcohol Use

Friday

Saturday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Students were also asked about a series of consequences of alcohol useboth direct (resulting from their own drinking) and indirect (resulting from other students drinking)1.

1

These questions are used with permission from the Harvard School of Health.

Indirect Consequences The data regarding students experiencing consequences as a result of other students drinking are presented in Table 2. These questions were asked of students who drink and students who do not. These questions have been used in drinking surveys going back to 2003, and data from 2006, 2008, and 2011 are provided for comparison points. 57.5% of students reported having had to baby-sit a student who drank too much and similar numbers (55.7%) had their studying or sleep interrupted during this academic year. 32.1% had been insulted or humiliated, and 24.0% had had a serious argument or quarrel as a result of someone elses drinking during this academic year. From 2003 (not shown) to 2006, there was a general upward trend in negative indirect consequences. Those consequences peaked in 2006 and 2008 and since that time have declined (Table 2). Table 2. Percentages of Students Experiencing Indirect Consequences from Other Students Drinking Indirect Consequences 2006 (%) 2008 (%) 2011 (%) 2013 (%) Had to baby-sit a student who drank too much 64.0 65.7 62.7 57.5 Had your studying or sleep interrupted 70.5 66.0 59.7 55.7 Been insulted or humiliated 36.9 40.6 36.4 32.1 Had a serious argument or quarrel 44.5 38.6 30.9 24.0 Had your property damaged 31.4 21.9 17.0 17.9 Been pushed, hit, or assaulted 20.1 17.7 14.0 12.4 Been a victim of unwanted sexual experience 5.8 5.5 6.2 6.3 Direct Consequences All student participants reported on a variety of physical, academic, interpersonal, legal, and sexual consequences they experienced as a result of their own drinking during the current academic year2. 60.4% reported having had a hangover or headache the morning after drinking, similar to the level in 2011 (60.5%) and lower than in 2008 (68.1%) (Table 3). Just less than half reported having felt sick to their stomach or thrown up (47.3%) and being unable to remember part of the previous evening (46.4%) (Table 3). 22.8% reported missing a class because of their alcohol use, compared to 25.2% in 2011 (Table 3). 31.0% reported doing something they later regretted, compared to 29.8% in 2011 (Table 3). Table 3. Percentages of Students Experiencing Physical, Academic & Interpersonal Consequences from Drinking Direct Consequences: Physical 2008 (%) 2011 (%) 2013 (%) Had a hangover/headache the morning after drinking 68.1 60.5 60.4 Felt sick to your stomach or thrown up 49.3 45.1 47.3 Been unable to remember a part of the previous evening 48.1 43.0 46.4 Been hurt or injured 14.6 12.3 15.8 Gotten into a physical fight 7.3 5.8 4.9 Direct Consequences: Academic Missed class 32.4 25.2 22.8 Gotten behind in school work 26.4 22.0 18.2 Had difficulty concentrating in class 24.2 19.8 15.5 Performed poorly on an assignment or test 15.6 12.6 10.9 Direct Consequences: Interpersonal Done something you later regretted 37.1 29.8 31.0 Become rude, obnoxious, or insulting 36.5 28.5 25.3 Felt guilty about your drinking 28.4 22.8 22.3

These percentages represent all respondents. In several cases, the questions asked were also asked in previous surveys on student drinking. Comparison data are available.

In addition, 4.6% indicated they had driven under the influence, a substantial decrease from 2008 (Table 4). 4.1% reported having damaged property or set off a false alarm (Table 4). Moreover, 7.1% reported having had sex when they didnt really want to, and 2.7% had been pressured or forced to have sex with someone when they had been too drunk to prevent it (Table 4). Lastly, and similar to findings from previous years, students who engaged in high-risk drinking were significantly more likely to experience all of the consequences when compared to non-high-risk drinkers. Frequent high-risk drinkers were at the greatest risk (analysis not shown). Table 4. Percentages of Students Experiencing Legal & Sexual Consequences from Drinking 2008 Direct Consequences: Legal (%) Driven under the influence 7.4 Damaged property or set off a false alarm 6.3 Gotten in trouble at school 5.9 Gotten in trouble with the police 5.3 Direct Consequences: Sexual Had sex when you didnt really want to 9.3 Been pressured or forced to have sex with someone when you 3.2 were too drunk to prevent it Pressured or forced someone to have sex with you after you had been drinking 2.6 Protective and Risk Behaviors Another section of the survey included questions regarding protective and risk behaviors when drinking alcohol. The following findings represent only students who drink. The percentages are for those students who indicated they usually or always engage in these behaviors. More responsible drinking is associated with a higher percentage and with a higher average score. With the exceptions of students intentionally eating food before drinking (74.0% usually or always) and keeping track of how many drinks they have had (53.4%), most students do not frequently practice protective behaviors that will reduce their risks related to alcohol (Table 5). For example, typically students rarely or sometimes (based on the average scores) alternate drinking alcoholic drinks with non-alcoholic beverages, pace their drinking to no more than one drink per hour, think about their BAC to reduce risks, or intentionally mix their drinks with less alcohol than normal (Table 5). In general, the percentages of students practicing protective behaviors increased from 2008 to 2011 (not shown), suggesting that educational efforts are having an impact, but have plateaued somewhat since 2011. Table 5. Protective Behaviors When Drinking (Drinkers Only) Behavior Intentionally eat food or a meal before drinking Keep track of how many drinks youve had Set a personal limit of how many drinks youll have during a drinking occasion Alternate alcoholic drinks with water or other nonalcoholic beverages Pace your drinking to no more than one drink per hour Think about your BAC in order to reduce risks associated with alcohol consumption Intentionally mix your drinks with less alcohol than normal % Usually or Always 2011 2013 68.0 74.0 56.1 53.4 34.4 21.9 21.8 18.6 15.8 33.0 23.3 18.8 17.9 16.5 Average* 2011 3.73 3.44 2.84 2.54 2.45 2.20 2.44 2013 3.89 3.43 2.83 2.62 2.42 2.21 2.48

2011 (%) 4.7 4.5 4.4 4.3 8.0 3.1 1.9

2013 (%) 4.6 4.1 3.5 2.5 7.1 2.7 1.4

* Scale: 1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=usually, 5=always. The higher the average the more frequently students are engaging in drinking behaviors that will reduce their risk.

In Table 6, data related to risk behaviors associated with alcohol consumption are provided. The percentages are for those students who indicated they rarely or never engage in these behaviors. More responsible drinking is associated with a higher percentage. The opposite is true for the average scores; the lower average is associated with more responsible drinking behavior. Of students who drink, 66.1% reported that they rarely or never chug alcohol, and 38.2% seldom choose a drink containing a higher alcohol concentration. However, only 24.6% reported the same when asked about playing drinking games, indicating that playing drinking games is the most common risk behavior among drinkers. In addition, only 27.6% of students who drink are unlikely to pre-game, and only 26.8% are unlikely to do shots. These percentages demonstrate an increase in risk behaviors since 2011. Table 6. Risk Behaviors When Drinking (Drinkers Only) Behavior Chug alcohol (e.g., keg stands, beer funnels) Choose a drink containing a higher alcohol concentration Pre-game (start drinking before going out) Do shots Play drinking games % Never or Rarely 2011 2013 68.5 66.1 44.3 38.2 37.1 27.6 31.5 26.8 28.7 24.6 Average* 2011 1.98 2.52 2.99 3.00 3.04 2013 2.09 2.71 3.26 3.18 3.18

* Scale: 1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=usually, 5=always. The lower the average, the more frequently students are engaging in drinking behaviors that will reduce their risk

You might also like

- Brandy & LiqueursDocument13 pagesBrandy & Liqueursjavaidbhat100% (1)

- Cape Chemistry Unit 2 LabsDocument85 pagesCape Chemistry Unit 2 LabsNalini Rooplal69% (13)

- Organic Syntheses Collective Volume 3Document1,060 pagesOrganic Syntheses Collective Volume 3caltexas100% (5)

- Final Project Report On Ub GroupDocument276 pagesFinal Project Report On Ub GroupRishi KumarNo ratings yet

- Questions On Alcoholic BeveragesDocument5 pagesQuestions On Alcoholic BeveragesRahul jajoriaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Chapter 1 5Document14 pagesThesis Chapter 1 5Felicity Mae Dayon BaguioNo ratings yet

- Binge DrinkingDocument16 pagesBinge DrinkingHanJiwonNo ratings yet

- An Undergraduate Thesis Presented To The Faculty of The College of EducationDocument28 pagesAn Undergraduate Thesis Presented To The Faculty of The College of EducationJean MaltiNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1.docx ResearchDocument11 pagesCHAPTER 1.docx Researchgaea louNo ratings yet

- Alkanes, Alkenes and AlkynesDocument85 pagesAlkanes, Alkenes and AlkynesYoichi Kho100% (1)

- List of Local Wine Importers and Distributors - : SingaporeDocument3 pagesList of Local Wine Importers and Distributors - : SingaporeSimone Sacchi100% (2)

- Walwal Now, Aral Later: The Effect of Alcohol Consumption To Mechanical Engineering Students' Academic PerformanceDocument18 pagesWalwal Now, Aral Later: The Effect of Alcohol Consumption To Mechanical Engineering Students' Academic Performancetoni50% (2)

- Practical Research GilDocument14 pagesPractical Research Giljohn lloyd gil100% (1)

- Chanakya National Law University: Project of Sociology ON Liquor Ban in BiharDocument21 pagesChanakya National Law University: Project of Sociology ON Liquor Ban in BiharAntra AzadNo ratings yet

- English 202 Final PaperDocument13 pagesEnglish 202 Final Paperapi-242011942No ratings yet

- Alcohol ConsumptionDocument7 pagesAlcohol ConsumptionAbel seyfemichaelNo ratings yet

- Research Methods - Final PaperDocument9 pagesResearch Methods - Final Paperapi-623352013No ratings yet

- Use of Soft Drinks and Its Effects Among High School Students of KottayamDocument6 pagesUse of Soft Drinks and Its Effects Among High School Students of Kottayamchinju shajanNo ratings yet

- AMA Computer College Caloocan: 263 UE Tech Road, Caloocan CityDocument9 pagesAMA Computer College Caloocan: 263 UE Tech Road, Caloocan CityRonnie Serrano PuedaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology Binge Drinking Among College Age Individuals United StatesDocument8 pagesEpidemiology Binge Drinking Among College Age Individuals United Statesapi-550096739No ratings yet

- Señor Tesoro Academy Senior High SchoolDocument67 pagesSeñor Tesoro Academy Senior High SchoolMarilyn Cercado FernandezNo ratings yet

- DR Mike Proposal EditsDocument8 pagesDR Mike Proposal EditsOladele RotimiNo ratings yet

- Use of Soft Drinks and Its Effect Among High School Students of KottayamDocument6 pagesUse of Soft Drinks and Its Effect Among High School Students of KottayamBijimol RajanNo ratings yet

- College Students Perception On Their Daily Food ChoiceDocument14 pagesCollege Students Perception On Their Daily Food ChoiceNguyễn Thiên DiNo ratings yet

- ScalesDocument5 pagesScalesPiinkeNo ratings yet

- Research Notes 2Document2 pagesResearch Notes 2api-458705471No ratings yet

- Michelles Presentation PR2Document29 pagesMichelles Presentation PR2Monica JoyceNo ratings yet

- Practical Research: Presented By: Erica Rose H. Garcia Nicojireh J. VelascoDocument21 pagesPractical Research: Presented By: Erica Rose H. Garcia Nicojireh J. VelascoLogsssNo ratings yet

- Chapter No 1: Introduction & BackgroundDocument39 pagesChapter No 1: Introduction & Backgroundusman_buttNo ratings yet

- HALE COUNTY - Plainview ISD - 2007 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesHALE COUNTY - Plainview ISD - 2007 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument8 pagesResearchLucilleNo ratings yet

- HALE COUNTY - Plainview ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesHALE COUNTY - Plainview ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S021265672030127X MainDocument2 pages1 s2.0 S021265672030127X MainenzoNo ratings yet

- LEON COUNTY - Oakwood ISD - 2008 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesLEON COUNTY - Oakwood ISD - 2008 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- Thesis Pr1 IijimaDocument16 pagesThesis Pr1 IijimaAnonymous yUUVGwwOtNo ratings yet

- LAMB COUNTY - Springlake-Earth ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesLAMB COUNTY - Springlake-Earth ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence and Associated Factors of Alcohol Use During Pregnancy Among Pregnant Women in The Buea Town Health CenterDocument70 pagesThe Prevalence and Associated Factors of Alcohol Use During Pregnancy Among Pregnant Women in The Buea Town Health CenterFavour ChukwuelesieNo ratings yet

- MAS306 BSM AS 3A The Impact of Alcohol Use Disorders On Mortality Rates - A Friedmans Test Approach - Edit - 1681785019531 - Edit - 1684061512375Document14 pagesMAS306 BSM AS 3A The Impact of Alcohol Use Disorders On Mortality Rates - A Friedmans Test Approach - Edit - 1681785019531 - Edit - 1684061512375Erica Joy EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Alcohol Consumption Among Emmanuel Alayande College of Education StudentsDocument16 pagesFactors Influencing Alcohol Consumption Among Emmanuel Alayande College of Education StudentsCentral Asian Studies100% (2)

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument5 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundKaye Jelai De LeonNo ratings yet

- PANOLA COUNTY - Beckville ISD - 2005 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument9 pagesPANOLA COUNTY - Beckville ISD - 2005 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- 3 Introduction 10.12Document10 pages3 Introduction 10.12Barbie QueNo ratings yet

- Patterns and Average Volume of Alcohol Use Among Women of Childbearing AgeDocument10 pagesPatterns and Average Volume of Alcohol Use Among Women of Childbearing AgeJessica Jean AllardNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument24 pagesResearchLuizalene Jacla AcopioNo ratings yet

- LEON COUNTY - Oakwood ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesLEON COUNTY - Oakwood ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- CORYELL COUNTY - Evant ISD - 1996 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument6 pagesCORYELL COUNTY - Evant ISD - 1996 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- HALE COUNTY - Plainview ISD - 2001 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument8 pagesHALE COUNTY - Plainview ISD - 2001 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- PANOLA COUNTY - Beckville ISD - 2008 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesPANOLA COUNTY - Beckville ISD - 2008 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Alcohol On Juvenile Delinquency To The Study O1Document8 pagesThe Effects of Alcohol On Juvenile Delinquency To The Study O1althea caballero100% (1)

- HABERMAN SurveyAlcoholDrug 1994Document17 pagesHABERMAN SurveyAlcoholDrug 1994vushe152No ratings yet

- Lily Szymanski Sona Article Interactive Effects of Drinking History and Impulsivity On College DrinkingDocument2 pagesLily Szymanski Sona Article Interactive Effects of Drinking History and Impulsivity On College DrinkingLily SzymanskiNo ratings yet

- Effects of Alcohol IntroDocument10 pagesEffects of Alcohol Introapi-298164241No ratings yet

- The Effects of Early Consumption of Alcoholic Beverages To The Senior High School Students of The Fisher Valley College S.Y. 2018-2019Document7 pagesThe Effects of Early Consumption of Alcoholic Beverages To The Senior High School Students of The Fisher Valley College S.Y. 2018-2019Alexandrea Bella GuillermoNo ratings yet

- PR Ericka GroupDocument9 pagesPR Ericka GroupCharie HopeNo ratings yet

- TERRY COUNTY - Wellman-Union CISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesTERRY COUNTY - Wellman-Union CISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- HALE COUNTY - Plainview ISD - 2004 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument9 pagesHALE COUNTY - Plainview ISD - 2004 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- TYLER COUNTY - Woodville ISD - 2003 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument8 pagesTYLER COUNTY - Woodville ISD - 2003 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- COCHRAN COUNTY - Whiteface CISD - 2004 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument9 pagesCOCHRAN COUNTY - Whiteface CISD - 2004 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- Likitha Eradala Case Study On Teenage DrinkingDocument16 pagesLikitha Eradala Case Study On Teenage Drinkinglikhitha eradalaNo ratings yet

- Study Habits and The Level of Alcohol Use Among College StudentsDocument25 pagesStudy Habits and The Level of Alcohol Use Among College StudentsHafiz RoslanNo ratings yet

- DALLAS COUNTY - Desoto ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesDALLAS COUNTY - Desoto ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy Among University Students The Roles of Sports Type and GenderDocument10 pagesRelationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy Among University Students The Roles of Sports Type and Gendercab1048kzNo ratings yet

- GRAYSON COUNTY - S & S Cons. ISD - 2003 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument8 pagesGRAYSON COUNTY - S & S Cons. ISD - 2003 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- TYLER COUNTY - Woodville ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesTYLER COUNTY - Woodville ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- WHEELER COUNTY - Shamrock ISD - 2003 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument8 pagesWHEELER COUNTY - Shamrock ISD - 2003 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- O'donnell Isd - 1994 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument7 pagesO'donnell Isd - 1994 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- JOHNSON COUNTY - Keene (Private School) - 2004 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument9 pagesJOHNSON COUNTY - Keene (Private School) - 2004 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- Parents' Perceptions of Their Adolescents' Attitudes Towards Substance Use: By Ethnic DifferencesFrom EverandParents' Perceptions of Their Adolescents' Attitudes Towards Substance Use: By Ethnic DifferencesNo ratings yet

- Lab Report 1. Adkisson and Searcy.02.12Document8 pagesLab Report 1. Adkisson and Searcy.02.12madkissoNo ratings yet

- CrastinSK603NC010 CompleteDocument6 pagesCrastinSK603NC010 Completerajcoep88No ratings yet

- Paper Ethanol Corrosion Cavalcanti1987Document3 pagesPaper Ethanol Corrosion Cavalcanti1987Eduardo CavalcantiNo ratings yet

- Chemistry LL SyllabusDocument19 pagesChemistry LL SyllabusRajat Kumar VishwakarmaNo ratings yet

- Organic Synthesis. Functional Group InterconversionDocument57 pagesOrganic Synthesis. Functional Group InterconversionJennifer Carolina Rosales NoriegaNo ratings yet

- GPS Safety Summary GPS Safety Summary GPS Safety Summary GPS Safety SummaryDocument5 pagesGPS Safety Summary GPS Safety Summary GPS Safety Summary GPS Safety SummaryAndhi Septa WijayaNo ratings yet

- A Toast To The Good 'Ol DaysDocument4 pagesA Toast To The Good 'Ol DaysCamper EnglishNo ratings yet

- SmartBevNEER00One pagerENDocument2 pagesSmartBevNEER00One pagerENLourdes LandoniNo ratings yet

- Acc. Chem. Res. 1992,25, 504 Gif Chemistry PDFDocument9 pagesAcc. Chem. Res. 1992,25, 504 Gif Chemistry PDFCarlotaNo ratings yet

- Nota Kimia Carbon Compoun Form 5Document16 pagesNota Kimia Carbon Compoun Form 5akusabrina2012No ratings yet

- Physical ChemistryDocument6 pagesPhysical ChemistryAnand MurugananthamNo ratings yet

- Ujian 2 Form 5Document9 pagesUjian 2 Form 5Nazreen NashruddinNo ratings yet

- 02b PDFDocument19 pages02b PDFSyed Ali Akbar BokhariNo ratings yet

- Final MatterDocument119 pagesFinal MatterSonam ReddyNo ratings yet

- Process Block Diagram Oleochemicals (Rev. 0)Document4 pagesProcess Block Diagram Oleochemicals (Rev. 0)Muhammad Alfikri RidhatullahNo ratings yet

- Op 7001886Document10 pagesOp 7001886TąmąƦą UltƦąsNo ratings yet

- Behind The Scenes of AWPDocument5 pagesBehind The Scenes of AWPJayesh BoleNo ratings yet

- Controlador y CalibradorDocument374 pagesControlador y CalibradorIrving Pineda100% (1)

- Bairstow RiggingDocument168 pagesBairstow Riggingswhite336No ratings yet

- MIDTERM Mix. Vodka 5Document19 pagesMIDTERM Mix. Vodka 5Amos CalebNo ratings yet

- Review Solvatochromically Based Solvent-Selectivity TriangleDocument11 pagesReview Solvatochromically Based Solvent-Selectivity TriangleMarcos SilvaNo ratings yet

- Chem Volume 3Document170 pagesChem Volume 3Marc Laurenze CelisNo ratings yet