Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Module 5 Topic 12 Gender Human Rights and Journalism Workbook

Uploaded by

api-218218774Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Module 5 Topic 12 Gender Human Rights and Journalism Workbook

Uploaded by

api-218218774Copyright:

Available Formats

Module 5_Topic 12: Gender, Human Rights and Journalism

At the completion of this topic, you will be able to:

Trace the emergence of human rights discourses; Distinguish between signature, ratification and reservation in relation to human rights treaties; Discuss the content of some human rights treaties developed by the United Nations; Comment on the ratification (and non-ratification) of human rights conventions and treaties in the Pacific; and

Outline the main principles behind a human rights approach to journalism.

Recommended Reading

United Nations, CEDAW: Restoring Rights to Women, Chapter One: Human Rights: From General to Specific and Chapter Two: Making Women Human (p.11 -22)

This lecture begins with a broad introduction to human rights discourses and conventions. It then highlights the importance of human rights training for journalists. The purpose of this lecture is to establish a framework for studying The Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in lecture 2.

What are Human Rights? While the doctrine of human rights may be traced back to Renaissance Europe and to philosophers like Thomas Paine and John Stuart Mill, modern classifications of human rights as civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights are based on the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The UDHR was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 largely in response to the atrocities of World War II. Its underlying premise (like most other human rights discourses) is that All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. This means that as human beings we are all entitled to freedom, dignity, justice, equality and protection. These international norms are universal and help to protect people worldwide from severe political, legal and social abuses (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 1). Human rights are fundamental rights that are meant for everyone, regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, nationality, age, sex, political beliefs (or any other kind of beliefs), intelligence, disability, sexual orientation or gender identity. Since the 1980s, human rights was used by scholars and activists representing a wide range of social, political and economic perspectives from feminists to lawyers and economists. This doctrine was defined as: A philosophy of egalitarian social relations expressed in law through contracts between states and peoples, as individuals and social groups (1993, 5).

One of the main criticisms of the doctrine of human rights by proponents of cultural relativism is that it is based on universal standards or international norms that emphasize individualism, freedom of choice and equality. These universal standards do not allow an acceptance of specific cultural practices (for example, female genital mutilation) that sometime clash with a human rights agenda. The counterargument is that human rights conventions are merely guidelines that, when ratified, have the potential to promote the betterment of womens (and mens) social, political and economic status. How these guidelines are interpreted and implemented will differ from country to country. The following quotation

at the 2005 World Summit reaffirmed: The universal nature of human rights and freedoms is beyond question.

Signature, Ratification and Reservation Human rights treaties are addressed to states for them to comply with and enforce. Once a member state ratifies a convention or treaty, it is obliged to follow the standards or rules laid out in the convention. Here, it is important to clarify that there is a difference between signing a treaty and ratifying in. When a state signs a treaty, it is expressing its interest in the treaty and its intention to become a party to a treaty. Ratification (acceptance, approval and accession) involves consent by a state to be bound by and implement a treaty. A reservation is a unilateral statement (or statement made by one party when signing or ratifying a treaty) that excludes or modifies the original treaty.

Seven core human rights treaties include: The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR, 1966); The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR, 1966); The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD, 1965); The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, 1979); The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (CAT, 1984); The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989) and The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (CMW,1990).

Here, it is important to stress that: The Pacific region has by far the lowest ratification rates worldwide of the seven core international human rights treaties (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2005). This is clearly indicated in the table below.

Pacific Island Country Table of Treaty Ratification

CESCR Cook Islands Fiji

CCPR

CERD

CEDAW 1-Oct-75 (via NZ)

CAT

CRC 6-Jun-97

CRMW

10-Feb-73

28-Aug-85

13-Aug93

Kiribati

17-Apr-04

11-Dec95

Marshall Is. Micronesia Nauru 12-Nov-01 Signature 12-Nov-01 Signature

2-Mar-06 1-Sept-04 12-Nov01 Signature

4-Oct-93 5-May-93 27-Jul-94

Niue

1-Oct-85 (via NZ)

20-Dec95 4-Aug-95

Palau PNG Samoa 27-Jan-82 12-Jan-95 25-Sep-92

2-Mar-93 29-Nov94

Solomon Is. Tonga Tuvalu

17-Mar-82

17-Mar-82 6-May-02

10-Apr95

16-Feb-72 6-Oct-99

6-Nov-95 22-Sep95

Vanuatu

8-Sept-95

7-Jul-93

(Adapted from: http://www.rrrt.org/assets/Pacific%20Culture%20and%20Human%20Rights.pdf)

These low levels of ratification may be explained in terms of limited human and financial resources and the lack of knowledge or technical capacity to fulfill treaty obligations (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2005). Pacific Island countries are also more inclined to ratify and implement conventions which do not

upset internal powerful stakeholder groups like Churches and customary chiefs (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2005). When human rights treaties are ratified, the country ratifying the treaty needs to ensure that customary norms (for example Melanesia kustom and faa Samoa) do not conflict with the new laws.

The Pacific Plan, endorsed by Pacific Island Forum member countries in October, 2005, integrates human rights under its third pillar (the goal of good governance). The plan envisions a region that is respected for the quality of its governance, the sustainable management of its resources, the full observance of democratic values and for its defense and promotion of human rights (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2005). Initiative 12.5 urges member states to ratify and implement international and regional human rights conventions, covenants and agreements in the hope that it will result in improved transparency, accountability, equity and efficiency in the management and use of resources in the Pacific (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2005). Human rights issues of specific concern to the Pacific region and that are related to the seven core human rights conventions include: decreasing poverty; improving health services; better education facilities; improving gender equality; protecting cultural values and traditional knowledge; and improving political and social conditions. In the second part of this lecture, we will discuss the main principles behind a human rights approach to journalism.

A Human Rights Approach to Journalism As journalists play a critical role in informing the public on a range of issues and in shaping our understanding of the world we live in, they also have the opportunity to increase public awareness, to educate the public on their rights, and, above all, to help in monitoring human rights (Beman and Calderbank, 2008, 7). A comprehensive understanding of human rights treaties can enable journalists to report on rights violations from multiple perspectives and to present an in-depth analysis of issues. It is often argued that an increasing awareness on human rights issues can lead to a stronger and more informed civil society. Benman and Calderbank argue that: If the public know that violations will not be ignored, and that they can rely on their local paper to report accurately and without bias on what is going on, then they will be more confident in their news media sources (2008, 7).

Some broad human rights areas that journalists would benefit from an understanding of include: children, disabled persons, education, HIV, health, the environment and gender. Here is it critical to stress that that these areas often intersect with each other, for example, we can highlight intersections

between gender, disability, and health. We can also reflect on how one set of rights are dependent on another, for instance, the right to health and the right to education and information are closely interconnected.

What do you know about children and the right to education in the Pacific? How are women who are disabled doubly affected as women and as disabled people? What are some intersections between gender, sexuality and health?

A human rights approach tends to focus on the most disadvantaged groups. It centres on principles of participation, non-discrimination and empowerment. Active, free and meaningful participation (UN Declaration on the Right to Development) of all individuals (women and men), communities, civil societies and so forth, should be a priority for journalists. It is critical that the voices of marginalized groups are presented or heard when addressing an issue. These groups should also be asked solutions to the issue being discussed as they may be able to suggest a means of solving issues that impact on them on a daily basis.

The principle of non-discrimination aims to safeguard the rights of vulnerable and marginalized individuals and communities. Constantly reflecting on questions like Who is interviewed? Where they are interviewed? What information is reported on? (Beman and Calderbank, 2008 , 25) can help journalists to prevent power imbalances and contribute to the empowerment of rights holders.

A human rights approach stresses the end result should be empowerment (of a marginalized community or communities). Through the process of giving voice to the marginalized and the interventions made by the journalist while reporting the story, other communities may be empowered. Now that you have some knowledge of human rights discourses and treaties, the next lecture closely examines one human rights treaty that impacts on women globally and in the Pacific, The Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women.

Benman, Gabrielle and Daniel Calderbank (eds.) (2008) The Human Rights Based Approach to Journalism, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Jalal, Imrana, (April, 2006), Pacific Culture and Human Rights: Why Pacific Island Countries Should Ratify Human Rights Treaties, available online at: http://www.rrrt.org/assets/Pacific%20Culture%20and%20Human%20Rights.pdf [accessed 7 September, 2011]

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Human Rights, available online at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rights-human/ [accessed 7 September, 2011]

United Nations, The Vienna Convention, 23 May, 1969, available online at: http://untreaty.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf [accessed 29 August, 2011]

Exercises

Exercise 1: Human Rights E-Games (15 minutes) If you have access to a computer, spend the first 15 minutes of the tutorial playing some of these online human rights e-games: http://www.youth-egames.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=40&Itemid=84 Discuss your responses to these games in groups.

Exercise 2: Culture versus Human Rights (20 minutes) Read the following story from The Observer (guardian.co.uk) and answer the questions that follow: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/feb/21/south-africa-polygamy-zuma/print

Discussion Questions: 1) Clearly outline the debate between polygamy and human rights in this news story. 2) Do you agree that polygamy is oppressive of women? Explain your answer. 3) Where is the reporter positioned in this story? Do you think he has intervened in the debate? If so, how? 4) Discuss the function of the headline and the photograph in this story. 5) If you were asked to write a story on polygamy, what approach would you take? Exercise 3: Racism and Religion (15 minutes) Read this story from The Fiji Times Online: http://www.fijitimes.com/story.aspx?id=115337

Discussion Questions: 1) List the human rights violations in the article above. 2) Which UN Convention/s can protect individuals from such forms of discrimination? 3) Comment on the style used by the journalist to broach this sensitive issue.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

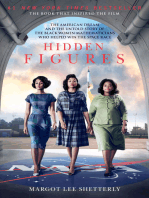

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Interpretation of Statutes - Notes For ExamsDocument31 pagesInterpretation of Statutes - Notes For ExamsMrinalBhatnagar100% (2)

- Kami Export - Mariam Abdo - Chief John Ross LetterDocument2 pagesKami Export - Mariam Abdo - Chief John Ross LetterMariam AbdoNo ratings yet

- The Dividing Line Wansolwara FeatureDocument3 pagesThe Dividing Line Wansolwara Featureapi-218218774No ratings yet

- Tempo Semanal Feature August WansolwaraDocument3 pagesTempo Semanal Feature August Wansolwaraapi-218218774No ratings yet

- Module 3 Topic 6 Gender and Print Media WorkbookDocument6 pagesModule 3 Topic 6 Gender and Print Media Workbookapi-218218774No ratings yet

- Module 2 Topic 5 Gender Sensitivity in The Media-WorkbookDocument7 pagesModule 2 Topic 5 Gender Sensitivity in The Media-Workbookapi-218218774No ratings yet

- Module 1 Topic 1 Introduction To Gender WorkbookDocument8 pagesModule 1 Topic 1 Introduction To Gender Workbookapi-218218774No ratings yet

- 3 Oblicon Prefinals PDFDocument35 pages3 Oblicon Prefinals PDFJohn Anthony B. LimNo ratings yet

- Mozambique Final Report 1feb17Document23 pagesMozambique Final Report 1feb17Verônica Da Graça Álvaro ManhenjeNo ratings yet

- Record Keeping For Delay Analysis PDFDocument12 pagesRecord Keeping For Delay Analysis PDFKarthik PalaniswamyNo ratings yet

- In The Lahore High Court Lahore Judicial Department: Judgment SheetDocument61 pagesIn The Lahore High Court Lahore Judicial Department: Judgment SheetUmair ZiaNo ratings yet

- Extrinsic MaterialsDocument3 pagesExtrinsic MaterialsjarjarbrightNo ratings yet

- ILO and IndiaDocument7 pagesILO and IndiaGlobal Justice AcademyNo ratings yet

- National Interest: Meaning, Components and MethodsDocument13 pagesNational Interest: Meaning, Components and MethodsAyesha FarooqNo ratings yet

- Public International Law - Landmark CasesDocument13 pagesPublic International Law - Landmark CasesKarla Marie TumulakNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-52265 Occena Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesG.R. No. L-52265 Occena Vs ComelecAronJamesNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full International Economics 8th Edition Husted Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full International Economics 8th Edition Husted Test Bank PDFwillardnelsonmn5b61100% (10)

- Petition 494 of 2014Document15 pagesPetition 494 of 2014Diana WangamatiNo ratings yet

- Susanne Zwingel. From Intergovernmental Negotiations Nto Subnational Change PDFDocument27 pagesSusanne Zwingel. From Intergovernmental Negotiations Nto Subnational Change PDFManuRamírezNo ratings yet

- International Business Law and Its Environment 9th Edition Schaffer Agusti Dhooge Test BankDocument23 pagesInternational Business Law and Its Environment 9th Edition Schaffer Agusti Dhooge Test Bankmelvin100% (22)

- Research Report On Child Protection and Child Social ProtectionDocument160 pagesResearch Report On Child Protection and Child Social ProtectionRepoa Tanzania100% (2)

- SC No 20 of 2011Document238 pagesSC No 20 of 2011SudheerRawatNo ratings yet

- 20161027-Delhi High Court LPA 222 of 2013 Jadhav Vishwas Haridas Vs Union Public Service Commission - SRB27102016LPA2222013 PDFDocument22 pages20161027-Delhi High Court LPA 222 of 2013 Jadhav Vishwas Haridas Vs Union Public Service Commission - SRB27102016LPA2222013 PDFDisability Rights AllianceNo ratings yet

- Saguisag Vs Ochoa CaseDocument1 pageSaguisag Vs Ochoa CaseBrylle DeeiahNo ratings yet

- Legal DiscourseDocument257 pagesLegal DiscourseThành PhanNo ratings yet

- Women Migrants Rights Under International Human Rights LawDocument6 pagesWomen Migrants Rights Under International Human Rights LawbbanckeNo ratings yet

- Lecture Ii - Defination and ConventionsDocument36 pagesLecture Ii - Defination and Conventionssimon eshetuNo ratings yet

- Case 5 Secretary of Justice Vs LantionDocument2 pagesCase 5 Secretary of Justice Vs LantionJairus Adrian VilbarNo ratings yet

- Qatar V Bahrain-2Document4 pagesQatar V Bahrain-2Joannalyn Libo-onNo ratings yet

- PIL-sem 4Document18 pagesPIL-sem 4Ishika ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Pinay Jurist: Bar Exam 2016 Suggested Answers in Political LawDocument41 pagesPinay Jurist: Bar Exam 2016 Suggested Answers in Political LawJohn Kayle BorjaNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law Case DigestsDocument9 pagesTransportation Law Case DigestsScents GaloreNo ratings yet

- Treatment Aliens : Doctrine WithDocument5 pagesTreatment Aliens : Doctrine WithMika SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Consular and Diplomatic Protection Legal Framework in The EU Member StatesDocument721 pagesConsular and Diplomatic Protection Legal Framework in The EU Member StatesPaulo RamosNo ratings yet

- Legality of The Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons CaseDocument11 pagesLegality of The Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons CaseJereca Ubando JubaNo ratings yet