Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Building A Stronger Board: Corporate Governance

Uploaded by

pramit04Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Building A Stronger Board: Corporate Governance

Uploaded by

pramit04Copyright:

Available Formats

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

Dont start something you cant nish Peer review? Most of your directors time is spent in the air

Building a stronger board

Robert F. Felton Alec Hudnut Valda Witt

162

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

IGURING OUT WHAT A BOARD of directors should look like and how it should work with management is a tricky task about which few agree. Diferent companies have diferent needs; some call for an active board, others for a quieter role. Given the growing performance pressure from shareholders, CEOs should devote some thought to the role that their board plays.

Corporations in the United States generally fall into three camps on this issue. Many CEOs prefer their boards to play a strictly advisory role. Crises and external events drive a second group of CEOs to strengthen their boards, at least enough to satisfy their shareholders. Unfortunately, they sometimes have to do this in a hurry, which can do more harm than good, particularly if the board members themselves are resistant to change. Then there is a third group: proactive CEOs looking for another way to improve company performance who can see the long-term benets of an independent, involved board. For many companies, this third path is attractive, yet frightening. It takes a strong CEO to oversee the creation of an active, value-adding board of directors. Achieving improvements in board performance can take time perhaps years. And once a CEO embarks on this process, he or she had better see it through. Board and shareholders may read any mid-course wavering as a sign of weakness or uncertain resolve. Before moving forward, most CEOs will want to be sure of the answers to a few key questions. To begin with, are major shareholders raising questions about your governance practices? If you are not under scrutiny today, how likely is it, given current trends, that you will

We would like to thank Jennifer van Heeckeren, a professor at the University of Oregon, and our colleague Michael Moore for their contributions to this article.

Bob Felton is a director and Alec Hudnut and Valda Witt are consultants in McKinseys Los Angeles oce. Copyright 1995 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

163

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

be tomorrow? Even if your company is performing well and your shareholders seem satised, it may still be wise to explore whether now is the time to begin building a stronger board: Is it worth going the extra mile to ensure that shareholders remain happy about the way your company is governed? Is the company itself getting full value from the board? Do you want directors who act as thought partners over the major issues facing the business? If so, can you count on your board to give a fully informed and objective opinion? Is the boards perception of your performance in tune with your own? If not, are you concerned about where that perception might lead if the companys performance took a turn for the worse? Are you prepared to spend a good deal of your time over the next year or more in leading a governance change efort? Can you weather any resistance you encounter from board members? CEOs who decide to build a more independent board can maximize the return on their efort by focusing on improving core board processes, which fall into four groups: board governance, management development and compensation, corporate strategy and performance, and business values and ethical oversight. Though there is nothing surprising about any of these categories, the details of how some of the best boards interpret and execute these Success lies in a boards taking responsibilities can be revealing.

full, independent responsibility for the smooth functioning of each of the core processes

Success lies above all in a boards taking full, independent responsibility and accountability for the smooth functioning of each of the core processes. This should probably be the province of dedicated board committees, which must be guided by a clear charter, stafed by directors who will commit the time and efort required, and chaired by a strong outside director who will exercise skillful and energetic leadership.

Governance

Redesigning the governance process to foster a boards independence from management can involve some challenging steps, such as adjusting the composition of the board or establishing formal mechanisms for evaluating its efectiveness (Exhibit 1). As well as these tough, long-term steps, which are discussed below, there are also some relatively easy measures that can

164

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

Exhibit 1

Board governance

Establish leadership independent of management Key components Board governance committee is charged with all board process responsibilities Only outside directors serve on key committees Audit Board governance Compensation Board membership criteria and director job descriptions are clear and documented Vast majority of directors should be outsiders, enough to staff and lead key committees Meetings are long Formal, enough for confidential substantive work performanceoriented peer Outside director- review system for only meetings are individual directors frequent and routine Many opportunities to create director turnover Board government processes are clearly communicated to shareholders and other stakeholders through the annual report, letters, or other channels Ensure optimal board composition Structure meetings to maximize board effectiveness Evaluate board effectiveness and make changes as needed Communicate with stakeholders

produce performance improvements almost immediately. One of these is to restructure meetings to maximize board efectiveness.

Meetings matter

Analyzing how directors spend their time can be revealing. In one large company, an average director spent more than half the time traveling to and from meetings. This is not at all unusual. Fewer, longer meetings (say, ve to seven full-day meetings a year) are generally more ecient. But no schedule is ideal for every board, and nding the one that is right for yours can be tricky. Interviews with directors reveal a variety of points of view on the best meeting schedule, inuenced by such factors as their location, job status, and personal style. Boards planning their schedule must consider both the work to be done and the needs of their members. As directors are busy people, oten with businesses of their own, management should ensure that professional and personal services such as secretaries, telephones, and transportation are available to board members during meetings. Such services can reduce interruptions, distractions, and delays, allowing directors to devote all their attention to the issues before the board. Many management experts and shareholder representatives also believe that external directors should occasionally meet without management and most directors agree. Meetings are inevitably inhibited by the presence of insiders, one director insisted. Surprises come out whenever the outside directors meet alone. Board members also feel that they should sometimes meet in less formal settings, and appreciate spending time together at

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

165

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

dinners or ofsite retreats. Many comment that some of the most efective meetings happen at dinners. Some board members feel that multiday ofsites are too disruptive, but others swear by them, asserting that they can fulll all the objectives of meeting informally in just one or two sessions a year.

Managing management

While boards generally acknowledge they are responsible for evaluating the CEO as part of the compensation setting process, the most efective among them extend their involvement to senior management. They ensure that management recruitment and development programs are in place, and review and approve succession plans for the CEO and all key managers. They formally evaluate these individuals performance and design compensation programs in line with the companys long- and short-term performance objectives (Exhibit 2).

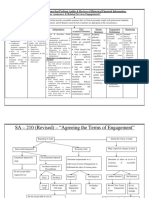

Exhibit 2

Management development and compensation

Develop tailored approach to assess companys management Key components Management development and compensation committee leads key processes CEO job description is reviewed and updated periodically Succession plans for CEO, direct reports, and their direct reports are reviewed annually with board Board elects CEO and approves appointments of direct reports CEO and direct reports are formally reviewed Directors review, approve, and administer compensation program Management development processes are clearly communicated to shareholders and other stakeholders Ensure critical management resources available Review senior management performance Reward on basis of performance Communicate with stakeholders

Directors have many opportunities to interact with Compensation is senior managers strictly tied to individual and company performance

Some of the best boards have set up a Management Development and Compensation Committee (MDCC) charged with leading eforts to evaluate, develop, and compensate management. This committee is responsible for initiating such critical management processes as succession planning and drating or reviewing the CEO job description to keep it up to date. Assigning this responsibility to a committee explicitly charged with this accountability is one way to put management assessment under the spotlight and make sure it receives regular board attention. One of the boards most important responsibilities is to elect a CEO and approve senior management appointments. In order to feel condent about such decisions, directors must be involved in evaluating and developing the current CEO and his or her potential successors. Several steps can be taken to foster this involvement:

166

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

A formal CEO evaluation process led by the MDCC, including the setting of annual goals, performance appraisals by all outside directors, and a selfevaluation by the CEO. Interestingly, the MDCC of one company has begun formally interviewing the CEOs direct reports as part of this process. An MDCC review of the CEOs evaluation of the top 20 (or more) key managers, presented to the full board. Increased exposure to the board for senior managers, with greater contact between directors and managers in both formal and informal settings. Possibilities include inviting a larger group of senior managers to make presentations to the board, and asking top managers to attend board meals and ofsite retreats.

Strategy and performance

Another critical role for the board is helping management to identify and resolve strategy and performance issues (Exhibit 3). This means that outside directors must have a solid understanding of both the industry and individual functions, as well as what creates value in the business. They must be aware of long- and near-term company goals and have timely access to nancial and other key measures so that they can monitor performance and hold management accountable. When deciding to strengthen a board, a CEO should focus particularly on the role it plays in strategy and performance.

Exhibit 3

Strategy and performance

Develop basic understanding of industry and company Key components Comprehensive director education emphasizes the companys fundamental value drivers Directors are routinely informed about relevant company, industry, and economic events Directors have access to senior management to discuss issues and ask questions Intensive, perhaps a multiday, annual board meeting reviews longterm goals, proposed strategic plans, and alternatives Board monitors a few critical performance measures on an ongoing basis Boards role in strategy development is outlined and clearly communicated to shareholders and other stakeholders Outside directors are available to meet important stakeholders Stay informed about major operating developments Confirm proposed strategy and monitor performance Communicate with stakeholders

Education and information

Most directors are in favor of a comprehensive introductory program for new board members, and stress the importance of continuing education throughout a directors tenure. Introductory education is a good idea, but education must be ongoing, one director said. Even the key performance

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

167

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

drivers need to be repeated, because you forget when you do not deal with them every day. All directors, new and current, should be encouraged to complete an introductory training program including site visits with business unit management. The involvement of operating managers also provides the secondary benet of increasing contact between manDirectors should never feel agers and directors. The board should review the companys assessment of its competitive position and monitor industry and economic trends continuously. To help in this process, board books should be designed to identify key agenda items clearly and concisely. If directors are to function as a peer group and sounding board for the CEO, they need to be kept fully informed about all major operating developments. They should never feel that they are in the dark or be surprised by news they read in the papers. Getting the right information to board members at the right time requires several steps. Directors should be routinely informed about relevant company, industry, and economic events. They should receive appropriate press clippings, subscriptions to selected industry journals, pertinent analyst reports, and any other high-level information that will keep them in touch with the state of the business. I want to know the concerns and Exhibit 4 thoughts of the people working in this business, A boards top five tasks declared one director. What are the issues? What Number of times selected by are competitors doing? directors as among 3 most

important roles of the board Monitor and evaluate long-term strategy 34

that they are in the dark or be surprised by news they read in the papers

Evaluate senior management performance Monitor and evaluate current corporate performance

28 25

Directors need full access to management so that they can discuss and ask questions about anything they believe to be important. The CEOs oce can handle any requests from directors for contact with management.

Understanding and monitoring strategy

Manage CEO succession Maintain legal and ethical practices 15 13

Source: Survey of 42 delegates attending Stanford Directors Conference, 1995

Any board needs to be generally well informed, but it especially needs to be aware of the companys strategy. In a recent survey, directors cited monitoring and evaluating a companys long-term strategy as their most important role (Exhibit 4). Yet board members oten complain that they do not even get a Dick and Jane picture of what the companys strategy is. While both directors and managers agree it is inappropriate for boards to

168

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

formulate strategy, many hold that they must review, appraise, and approve managements plans for a company. As one director put it, The boards role is to provide non-passive reactions to management proposals. In the words of governance specialist Ron Gilson, A good board provides a setting where the CEO has genuinely to justify the companys strategy and performance on a regular basis. Many companies have begun to hold ofsite sessions of several days where strategy is thoroughly discussed with the board. Eventually, this secures a strategy that the board has fully understood A good board provides a setting and ratied. An integral part of the strategy development process is to establish a set of operating measures focused on shareholder value creation which can be used to track the success of the chosen strategy over time. If the strategy cannot be measured, it may need further renement. Performance against these measures should be reported to the board periodically, with any deviations subjected to board scrutiny and discussion.

where the CEO has to justify the companys strategy and performance on a regular basis

Ethics and integrity

All companies are vulnerable to unethical behavior and its potentially devastating consequences. It is vital that managers and the board know where the corporation may be exposed and ensure that appropriate control systems are in place and reviewed at least annually. The most efective boards actively participate in setting boundaries for business values and ethics. They may develop or approve policies in such critical areas as nance and accounting, mergers and acquisitions, major capital expenditure, the environment, safety, employee relations, and legal and retirement obligations (Exhibit 5). These issues are typically addressed by audit, environmental, retirement, and other special committees.

Exhibit 5

Values, ethics, and financial integrity

Set boundaries Ensure processes in place Stay informed and monitor Communicate with stakeholders

Key components Independent discussion by outside board members of expectations and boundaries Consensus with top managers on expectations and boundaries Board committee(s) to oversee critical areas, eg audits, pension, health, environment, and safety Detail of major processes circulated to all relevant employees Mechanisms in place for routine and emergency notification of important events Directors have access to senior management to discuss issues and ask questions Boards role in processes clearly communicated to shareholders and regulatory agencies as appropriate

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

169

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

The benets of strong, independent board involvement in business ethics may be impossible to demonstrate conclusively. But what evidence there is tends to support independent review by the board. A recent study found that companies investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for aggressive reporting on nancial statements had fewer outsiders on their boards than the average rm, and these boards were generally less independent of management.1 Another study found that rms where management fraud occurred also had a smaller proportion of external directors than other companies.2 The independence and objectivity of a board can be crucial, particularly in preventing costly lapses.

Sharing with shareholders

Efective shareholder communication plays such an essential role in all four of the core board processes that it is worth thinking communication policies through carefully. Going beyond the bare minimum required to fulll SEC conditions in the proxy statement, for example shows that a company both appreciates its shareholders need to be well informed and values their involvement. The New Foundations Working Group, comprising prominent corporate executives, institutional investors, and academics, has produced a list of recommendations designed to improve communications between corporations and shareholders.3 Two fundamental principles underlie all the suggestions:

Efective communication with shareholders plays an essential role in all core board processes

Shareholders (especially the large ones) should be given opportunities to obtain information and provide feedback: A fuller understanding of the perspective of major investors and the broad opinion of the market can help senior managers and corporate directors to identify both sources of market support and sources of concern.

Senior management should be involved in the process: Communications should be structured so as to signal a serious commitment to seeking (on the part of the corporation) and to providing (on the part of investors) highlevel feedback that can potentially have a direct impact on policy.

Challenging, but possible

Making the renements outlined above can take a board a long way down the road toward performance improvement. For still higher achievement, there are further moves to make, especially in the core process of governance. These extra steps oten prove challenging and take a while to put into action.

1

For notes, see page 175.

170

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

Evaluating the evaluators

At every other level of a company, detailed performance standards with established measures and accountabilities are considered vital in achieving and sustaining high performance. Why should boards be the most prominent exception to this rule? Yet most boards, in our experience, hesitate to endorse the use of performance standards for themselves. They tend to be particularly uncomfortable with performance evaluation of individual directors. One board member protested, Evaluation is terribly dicult because on boards you share responsibility any evaluation would be highly subjective. Another stated simply, Peer review wont work. Evaluating the performance of the board collectively seems somewhat less controMost boards, in our versial, yet few boards do even this. But evaluation can be a powerful tool to develop and support high-performing board members. If directors are to take responsibility for creating and sustaining a strong board, they need to devise measures for distinguishing good performance from bad, as some of them acknowledge. One concerned board member complained, Directors are not held to a strict enough standard of performance. Perhaps a pass/fail evaluation system could be employed. Some form is necessary although everyone is reluctant. Another recommended, Make the renomination process more substantive. Since a boards efectiveness depends on the performance of its members, a formal, condential, and performance-oriented peer review system could be valuable for individual directors. At a minimum, board members should be renominated only ater their individual contributions have been thoroughly assessed. They should also meet objective standards concerning such things as current job status, attendance record, conicts of interest, acceptance of other directorships, and age. The board should conduct annual reviews of its own processes and make changes where necessary. One approach would be to interview directors regularly to identify areas where the functioning of the board could be improved. Many boards employ mechanical devices to create turnover, such as demanding that directors resign when they change jobs or retire. This can be a valuable strategy, and many directors support it, but it is unlikely to be enough in itself to instill the necessary performance ethic in a board that has not traditionally had one. There is no substitute for establishing and applying evaluation criteria to individual directors and/or the board as a whole. That said, we have yet to nd any companies that handle board evaluation very well.

experience, hesitate to endorse the use of performance standards for themselves

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

171

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

The right size and mix

If evaluating your board reveals performance gaps at the collective or individual level, you should consider adjusting the size of the board or its mix of members. While companies vary in the number of directors they need, boards that are too large encounter more coordination problems, and have diculty developing efective communication and teamwork. A recent study found A recent study found that that rms with smaller boards had rms with smaller boards had higher average prots than those with higher average prots than larger boards.4 And, while indepenrms with larger boards dence may be in the mind, another key factor in board efectiveness is the ratio of outside to inside members. Governance experts agree that boards should have a clear majority of outsiders.

The value of independence

Several academic studies have suggested that independent outsiders add real value to a company. One survey categorized a large random sample of companies according to their proportion of outside directors, and found that the group with the strongest external representation on its board also had the highest return on equity in the 1980s.5 Another study investigated investors reactions to company announcements of board appointments. On average, stock prices rose when independent outsiders were brought in.6 Practical experience tends to support these research ndings. Not only do shareholders and governance experts agree there should be a majority of outside directors, but many directors go even further, advocating that inside board members should number no more than three, and that ideally there should be Investors reactions to board only one the CEO. Experienced directors recognize that there are certain structural changes a board can make to secure efective, independent leadership. It should ensure that outside directors serve on and preferably lead the most important committees, including audit and compensation. Boards should also establish governance committees of three or four outside directors charged with all board process responsibilities, including the nomination of directors and committee assignments. Finally, many companies have created an executive committee consisting of the CEO and two or three outside directors that meets to approve major decisions such as acquisitions, divestitures, and major expenditures in

appointments generate rising stock prices when independent outsiders are brought in

172

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

emergencies where it is not possible to postpone matters until the next board meeting or to convene the full board by teleconference. Such executive committees should be viewed as emergency teams that will meet only to handle extraordinary events. An executive committee of outside directors and CEO is a good idea, a senior director of one large corporation remarked. However, the executive committee should not meet on a regular basis because this makes the rest of the board feel out of touch. My executive committee has not met at all in the last two years. It should be a standby, emergency committee.

Recruiting directors

The need for a majority of outside directors poses a problem for many boards. How can they recruit and retain a body of directors who are both independent and qualied for the job? There is a limited set of people, one director complained; Everybody has the same list, and most will not be available to serve. One way of extending the shortlist is to add the presidents and chief operating ocers of Fortune 500 companies to the traditional candidate pool of CEOs and well-known academics. As well as bringing experience and expertise, many presidents and COOs are enthusiastic about board membership and motivated to perform well. For one thing, being a director is good CEO training. For another, being appointed to another companys board may There is a limited set of be seen by their own company as a sign that people. Everybody has the they are CEOs in waiting. Another solution is to include CEOs from smaller corporations among the candidates. There are, ater all, only a few companies with revenues above $10 billion, but many more with revenues over $1 billion. The CEOs of these smaller companies deal with most of the same management challenges as do their counterparts in larger organizations. Companies attempting to enhance the diversity of their boards by recruiting more women and minority candidates may also nd that relying on the shortlist does not get them far. Search rms may be able to help identify a number of suitably qualied candidates. Recruiting strong board members can be hindered by diferences of opinion over what makes a good director. There are those who believe that You just need smart people with business sense. Ron Gilson asserts that The most important characteristic of a board member is that he ask good questions frequent, pointed questions. Some maintain that Directors have the responsibility to learn about and stay informed about

same list, and most will not be available to serve

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

173

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

an industry to which they might otherwise have little or no exposure. Others insist that directors must possess relevant industry experience, ideally as current CEOs. All agree, however, that the board should start the recruitment process by determining the skills and qualications needed for board membership at that time, and identifying several candidates who t the prole. This involves: Drating and reviewing board membership criteria and director job descriptions, recognizing that diferent roles on the board may demand diferent backgrounds and skills. Conducting a rigorous search to identify a number of qualied candidates for directorships. Led by the chairman of the governance committee, with input from other board members and top managers, this process may also be assisted Opportunities to learn, grow, by a suitable executive search rm. Establishing a set of practices and procedures that excite and energize a board may well make it easier to recruit talented directors. A signicant factor in attracting and retaining board members is the opportunity to learn and interact with peers in a stimulating environment, explained one experienced director. She had recently let a board because, as she put it, They were nice people, but there was nothing electrifying about the experience. It was sterile it had no life.

and contribute are for many the real attractions of a position on a strong and vital board

What to pay

If a company has trouble attracting the kind of board members that it wants, it should check whether its director compensation package is still competitive. Compensation is, of course, invariably controversial. Some experts insist that raising compensation has no proven efect on board performance, while others argue that $250,000 a year is only fair for a qualied and committed director. Until the right answer emerges if one exists a little pragmatism may be advisable. Accordingly, we recommend that before approaching prospective directors, the management committee should review the boards compensation package to ensure that it reects the responsibilities and time commitments that will be involved and compares with the remuneration ofered by peer companies. If compensation does need to be improved, consider options like paying directors in stock (or stock options). A recent academic study nds that the stock market reacts favorably to companies announcing the adoption of stock compensation plans for directors.7

174

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

BUILDING A STRONGER BOARD

In an independent and active board, the chairmen of core committees may merit higher compensation than other directors. Because their leadership responsibilities are both demanding and essential to the smooth functioning of the boards core processes, committee chairmen must be motivated to sustain high levels of commitment over time. Financial compensation is only one among many incentives, however, and it is oten not the decisive factor. Opportunities to learn, grow, and make a contribution are for many the real attractions of a position on a strong and vital board.

There is no universal formula for what boards should look like or how they should function. The possibilities are legion. But CEOs will be better able to understand the options and their associated risks and benets if they focus on the four basic processes of board governance, management development and compensation, corporate strategy and performance, and business values. In this way, they will acquire the insight necessary to judge whether they do indeed need to build a stronger board.

NOTES

1

Patricia Dechow, Richard G. Sloan, and Amy P. Sweeny, Causes and consequences of aggressive reporting policies, Working Paper, Harvard Business School, May 1994. Mark S. Beasley, An empirical analysis of the relation between corporate governance and management fraud, PhD dissertation, Michigan State University, 1994. Improving communications between corporations and shareholders: Overall ndings and recommendations, The New Foundations Working Group, Kennedy School of Government, Cambridge, Mass, January 1994. David Yermack, The superior performance of companies with small boards of directors, New York University Stern School of Business, Working Paper, 1995. Barry D. Baysinger and Henry N. Butler, Corporate governance and the board of directors: Performance efects of changes in board composition, Journal of Law and Economics, Volume 1, Number 1, Fall 1985. Stuart Rosenstein and Jefrey G. Wyatt, Outside directors, board independence, and shareholder wealth, Journal of Financial Economics, Volume 26, 1990. Scott Linn and Kenneth Martin, Director compensation and market reaction, University of Oklahoma College of Business, Working Paper, 1995.

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1995 NUMBER 2

175

You might also like

- The Certified Executive Board SecretaryFrom EverandThe Certified Executive Board SecretaryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- A CFO's Guide To Corporate GovernanceDocument8 pagesA CFO's Guide To Corporate GovernanceRonald Tres ReyesNo ratings yet

- Excellence in The Boardroom: 1. Carissa 2. Dita Anggraini 3. Nesia Ade Tantia 4. Siva FaoziahDocument32 pagesExcellence in The Boardroom: 1. Carissa 2. Dita Anggraini 3. Nesia Ade Tantia 4. Siva FaoziahSiva Faoziah FadillahNo ratings yet

- 2122 Bds U05 Ce01 Workshop GuideDocument6 pages2122 Bds U05 Ce01 Workshop GuideKaran UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Ten Things For Boards of Directors To Avoid Deloitte 091509Document4 pagesTen Things For Boards of Directors To Avoid Deloitte 091509Nguyen Quang NghiaNo ratings yet

- Effective Board MeetingsDocument4 pagesEffective Board MeetingsSheree WelchNo ratings yet

- Article NotesDocument11 pagesArticle NotesPriyanshi JainNo ratings yet

- Boards - When Best Practice Isn't EnoughDocument7 pagesBoards - When Best Practice Isn't EnoughEmanuela Magdala100% (1)

- Asdf RetDocument11 pagesAsdf RetAndrey YohanesNo ratings yet

- 04 044Document11 pages04 044Marwa Abdel RazekNo ratings yet

- The BODDocument55 pagesThe BODRosanna LombresNo ratings yet

- 7 Habits of Effective BoardsDocument3 pages7 Habits of Effective BoardsmrcindaiNo ratings yet

- 04 Relationship With ManagementDocument3 pages04 Relationship With ManagementSilentArrowNo ratings yet

- CHP 3Document14 pagesCHP 3Nazmul H. PalashNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Meeting Management, Minute Taking &Document19 pagesIntroduction To Meeting Management, Minute Taking &Jablack Angola MugabeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document17 pagesChapter 2jecille magalongNo ratings yet

- Governance and ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesGovernance and ResponsibilityKit Tze KiatNo ratings yet

- 20231215205228D6289 5.structuresandconsequencesDocument22 pages20231215205228D6289 5.structuresandconsequencestediprasetyo44No ratings yet

- Case Assignment: CEO Succession Planning, Selection and Performance AppraisalDocument4 pagesCase Assignment: CEO Succession Planning, Selection and Performance AppraisalKinza ZaheerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Board of DirectorsDocument43 pagesChapter 8 Board of DirectorsFATIN 'AISYAH MASLAN ABDUL HAFIZNo ratings yet

- CSR-Asmt 2 202201F0710Document21 pagesCSR-Asmt 2 202201F0710Jessy SimonNo ratings yet

- Redraw The Line Between The Board and The CEO: John C. SmileDocument3 pagesRedraw The Line Between The Board and The CEO: John C. Smilenoman100% (1)

- Corporate Governance (Self Study For Students)Document4 pagesCorporate Governance (Self Study For Students)akwadNo ratings yet

- Infographic: Do You Have A High-Impact Board of Directors?Document1 pageInfographic: Do You Have A High-Impact Board of Directors?OpenView Venture PartnersNo ratings yet

- ADL 08 Corporate Governance V2Document21 pagesADL 08 Corporate Governance V2Razz Mishra100% (3)

- Slides CG4Document22 pagesSlides CG4Phuong ThanhNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance Presentation Morvin Williams CCCUDocument29 pagesCorporate Governance Presentation Morvin Williams CCCUsahib lupanNo ratings yet

- Effective Operations & Best PracticesDocument11 pagesEffective Operations & Best PracticesSoonyoung KwonNo ratings yet

- Managing Director Chief ExecutiveDocument5 pagesManaging Director Chief ExecutivezaibeguyNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance PresentationDocument8 pagesCorporate Governance PresentationFloe MakumbeNo ratings yet

- 5.3. Board Meetings & Board StructuresDocument5 pages5.3. Board Meetings & Board StructuresThư Nguyễn Thị AnhNo ratings yet

- BWRR3123 AssignmentDocument55 pagesBWRR3123 AssignmentBaby KhorNo ratings yet

- Roles of The Chair and CEODocument4 pagesRoles of The Chair and CEOquadrospauloNo ratings yet

- BECG PowerPointDocument92 pagesBECG PowerPointHussain NazNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance SDocument12 pagesCorporate Governance SMariam AlraeesiNo ratings yet

- BoardMatters Quarterly, June 2012 - Audit Committees - Going Beyond The Ordinary - EY - United StatesDocument3 pagesBoardMatters Quarterly, June 2012 - Audit Committees - Going Beyond The Ordinary - EY - United StatesKwadwo AsaseNo ratings yet

- Effective Boards in Islamic FiDocument3 pagesEffective Boards in Islamic FihanyfotouhNo ratings yet

- Oliver Wyman CEO EvaluationDocument20 pagesOliver Wyman CEO EvaluationAbhilasha MunshiNo ratings yet

- BAC 04 Mid Term...Document25 pagesBAC 04 Mid Term...cheraimae840No ratings yet

- What Is Board of Directors (B of D) ?Document12 pagesWhat Is Board of Directors (B of D) ?J M LNo ratings yet

- How To Engage Your Board of Directors in A Borderless Competitive WorldDocument3 pagesHow To Engage Your Board of Directors in A Borderless Competitive WorldRituKukrejaNo ratings yet

- F8 - Audit and Assurance Chapter 2Document15 pagesF8 - Audit and Assurance Chapter 2Muhammad TahaNo ratings yet

- StructureDocument6 pagesStructureVengatesh SlNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - Mini Case: The Volkswagen Emissions ScandalDocument8 pagesChapter 10 - Mini Case: The Volkswagen Emissions ScandalNirvana ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Board ManualDocument5 pagesBoard ManualTwite_Daniel2No ratings yet

- L3 Role of Board MembersDocument7 pagesL3 Role of Board MembersvivianNo ratings yet

- MGT503 - Solved Repeated Questions in Current PapersDocument6 pagesMGT503 - Solved Repeated Questions in Current Paperskainatz891No ratings yet

- Board and Director EvaluationDocument3 pagesBoard and Director EvaluationNeha VermaNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Board of Directors in Corporate GovernanceDocument12 pagesThe Role of The Board of Directors in Corporate GovernancedushyantNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Board of Directors in Corporate GovernanceDocument12 pagesThe Role of The Board of Directors in Corporate GovernancedushyantNo ratings yet

- Us CCG Board Refreshment 012715Document1 pageUs CCG Board Refreshment 012715Charity ChikwandaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance - Christine Mallin - Chapter 8 - Directors and Board StructureDocument5 pagesCorporate Governance - Christine Mallin - Chapter 8 - Directors and Board StructureUzzal Sarker - উজ্জ্বল সরকার67% (3)

- NanoTool-2023-03-Choosing A New Board LeaderDocument3 pagesNanoTool-2023-03-Choosing A New Board LeaderrpercorNo ratings yet

- WWW Nacdonline Org BoardDevelopment Content CFM ItemNumbDocument2 pagesWWW Nacdonline Org BoardDevelopment Content CFM ItemNumbSanath FernandoNo ratings yet

- Kyambogo University Department of Lands and Architectural Studies Bachelor of Science Land Economics Principles of Management CourseworkDocument12 pagesKyambogo University Department of Lands and Architectural Studies Bachelor of Science Land Economics Principles of Management CourseworkDorothy MwesigyeNo ratings yet

- Ten Basic Responsibilities of Nonprofit BoardsDocument9 pagesTen Basic Responsibilities of Nonprofit BoardsempirechocoNo ratings yet

- A Senior LeadersGuide Leader-Led DevelopmentDocument24 pagesA Senior LeadersGuide Leader-Led DevelopmentKusumapriya007No ratings yet

- Fundamentals of OrganizationDocument28 pagesFundamentals of OrganizationchirkennurgetNo ratings yet

- Chapter 05 Board of Directors and Related IssuesDocument57 pagesChapter 05 Board of Directors and Related IssuesDuyên Nguyễn Hồng MỹNo ratings yet

- Comparing Several Means: AnovaDocument52 pagesComparing Several Means: Anovapramit04No ratings yet

- Weighting Cases: Factor % in Population / % in Sample. in Our Example With Assumed 8% of Officials in TheDocument1 pageWeighting Cases: Factor % in Population / % in Sample. in Our Example With Assumed 8% of Officials in Thepramit04No ratings yet

- ExercisesDocument1 pageExercisespramit04No ratings yet

- ExerciseDocument2 pagesExercisepramit04No ratings yet

- Kiams ContactsDocument4 pagesKiams Contactspramit04No ratings yet

- Acknowledgement: Mrs. Nivedita Dhal Project Co-Ordinator and H.O.D. (MBA)Document1 pageAcknowledgement: Mrs. Nivedita Dhal Project Co-Ordinator and H.O.D. (MBA)pramit04No ratings yet

- Certificate: Sparr DVDDocument44 pagesCertificate: Sparr DVDpramit04No ratings yet

- Systems of NonDocument63 pagesSystems of Nonpramit04No ratings yet

- Model Project On Improved Rice MillDocument50 pagesModel Project On Improved Rice Millpramit04No ratings yet

- X y X y X y X Y: Orientation Mathematics: Mock TestDocument3 pagesX y X y X y X Y: Orientation Mathematics: Mock Testpramit04No ratings yet

- Amount Expenditure Income and Expenditure - Pragati-08: (Excluding Borewell of Rs 24200)Document2 pagesAmount Expenditure Income and Expenditure - Pragati-08: (Excluding Borewell of Rs 24200)pramit04No ratings yet

- Culturals Expenses Sheet: S.No Item AmountDocument8 pagesCulturals Expenses Sheet: S.No Item Amountpramit04No ratings yet

- Culturals: Voucher No. Purpose Name of Claimant Paid DateDocument28 pagesCulturals: Voucher No. Purpose Name of Claimant Paid Datepramit04No ratings yet

- Budget FileDocument2 pagesBudget Filepramit04No ratings yet

- Deterministic ModelingDocument66 pagesDeterministic Modelingpramit04100% (1)

- Bajaj Auto LTD in Chile in UruguayDocument23 pagesBajaj Auto LTD in Chile in Uruguaypramit04No ratings yet

- Economics CasesDocument8 pagesEconomics Casespramit04No ratings yet

- What Is A Stock OptionDocument7 pagesWhat Is A Stock Optionpramit04No ratings yet

- Respective Obligations: Discharge of ContractDocument18 pagesRespective Obligations: Discharge of Contractpramit04No ratings yet

- About Chilean MarketDocument3 pagesAbout Chilean Marketpramit04No ratings yet

- Kle BL M5Document19 pagesKle BL M5pramit04No ratings yet

- Kle BL M9Document20 pagesKle BL M9pramit04No ratings yet

- Factory Physics PrinciplesDocument20 pagesFactory Physics Principlespramit04100% (1)

- Seminar On Refinery Maintenance Management and TPM Held at Saudi Aramcos Ras Tanura RefineryDocument4 pagesSeminar On Refinery Maintenance Management and TPM Held at Saudi Aramcos Ras Tanura Refinerychaitanya_kumar_13No ratings yet

- Supreme Court Reports (2012) 8 S.C.R. 652 (2012) 8 S.C.R. 651Document147 pagesSupreme Court Reports (2012) 8 S.C.R. 652 (2012) 8 S.C.R. 651Sharma SonuNo ratings yet

- Ituralde Vs Falcasantos and Alba V CADocument4 pagesIturalde Vs Falcasantos and Alba V CALouie Ivan MaizNo ratings yet

- Baldrige Flyer Category 1 3apr08Document2 pagesBaldrige Flyer Category 1 3apr08Tomi KurniaNo ratings yet

- Luzviminda Visayan v. NLRC and Fujiyama RestaurantDocument4 pagesLuzviminda Visayan v. NLRC and Fujiyama RestaurantbearzhugNo ratings yet

- CrimPro Codal Memory Aid FinalsDocument33 pagesCrimPro Codal Memory Aid FinalsMartin EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Law On Natural Resources ReviewerDocument130 pagesLaw On Natural Resources ReviewerAsh CampiaoNo ratings yet

- Culture of InnovationDocument6 pagesCulture of InnovationppiravomNo ratings yet

- (Written Work) & Guide: IncludedDocument10 pages(Written Work) & Guide: IncludedhacknaNo ratings yet

- TKD Amended ComplaintDocument214 pagesTKD Amended ComplaintHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- United States v. Arthur Pena, 268 F.3d 215, 3rd Cir. (2001)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Arthur Pena, 268 F.3d 215, 3rd Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brand Collaboration Agreement: (Labevande)Document3 pagesBrand Collaboration Agreement: (Labevande)Richard Williams0% (1)

- Personality and Self ImageDocument22 pagesPersonality and Self ImageApeksha Gupta100% (2)

- 2017 Annual Report: The Robby Hague Memorial Scholarship FundDocument6 pages2017 Annual Report: The Robby Hague Memorial Scholarship FundrghscholarshipNo ratings yet

- Easement Act Architecture Module 4 Professional Practice 2 15arc8.4Document17 pagesEasement Act Architecture Module 4 Professional Practice 2 15arc8.4Noothan MNo ratings yet

- 01 Section T1 - Invitation To Tender VFDocument12 pages01 Section T1 - Invitation To Tender VFSatish ShindeNo ratings yet

- C54 US Vs ArceoDocument1 pageC54 US Vs ArceoRon AceroNo ratings yet

- Spec Pro - Digests Rule 91 Up To AdoptionDocument11 pagesSpec Pro - Digests Rule 91 Up To Adoptionlouis jansenNo ratings yet

- 5 Brahmin Welfare - 01sept17Document17 pages5 Brahmin Welfare - 01sept17D V BHASKARNo ratings yet

- Metacognitive Reading ReportDocument2 pagesMetacognitive Reading ReportLlewellyn AspaNo ratings yet

- LeadershipDocument34 pagesLeadershipErika BernardinoNo ratings yet

- Farinas v. Executive Secretary GR 147387 - 12-10-03Document2 pagesFarinas v. Executive Secretary GR 147387 - 12-10-03John WeeklyNo ratings yet

- Offer Advice Very Carefully (Ed Welch)Document1 pageOffer Advice Very Carefully (Ed Welch)John FieckNo ratings yet

- GhararDocument5 pagesGhararSiti Naquiah Mohd JamelNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Palliative CareDocument21 pagesChapter 4 Palliative CareEINSTEIN2DNo ratings yet

- PCGT PetitionDocument3 pagesPCGT PetitionMoneylife Foundation100% (1)

- The Core Values of The Professional NurseDocument9 pagesThe Core Values of The Professional NurseEdmarkmoises ValdezNo ratings yet

- 53 Standards On Auditing Flowcharts PDFDocument22 pages53 Standards On Auditing Flowcharts PDFSaloni100% (1)

- Demand LetterDocument5 pagesDemand LetterAryan Ceasar ManglapusNo ratings yet

- PS Early Childhood Education PDFDocument69 pagesPS Early Childhood Education PDFHanafi MamatNo ratings yet