Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sample Pages From Romantic Women Writers Reviewed Part III - Gentleman's Magazine, 1791

Uploaded by

Pickering and ChattoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sample Pages From Romantic Women Writers Reviewed Part III - Gentleman's Magazine, 1791

Uploaded by

Pickering and ChattoCopyright:

Available Formats

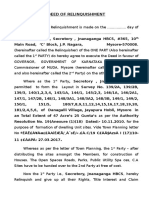

GENTLEMANS MAGAZINE

Barbauld, Anna Laetitia

61:2 no. 12 (December), pp. 11246. 205. Reflections on the Slave-Trade; with Remarks on the Policy of its Abolition. In a Letter to a Clergyman in the County of Suffolk. By G. C. P. The great question of abolition, which has agitated the minds of our countrymen for the two last years, having been brought to an issue in the last session of the British Parliament, and in France by a much earlier resolution of the National Assembly, we cannot close the discussion of it better than in the words of our brethren the Monthly Reviewers, whose understanding regulates their feelings in a just degree; and who, without triumphing over the fallacies they point out, do not hesitate to detect them in the justest and fullest manner. In vain do the feelings of the tender sex urge them to vent their resentment against those senators who voted against abolition, in the keen severity of Mrs. Barbaulds and other poetical pens.* In vain do the patriots call upon our wives and daughters, our sisters and aunts, our mistresses and Abigails, to associate against the use of sugar till Negroes cease to be employed in manufacuring it, or till there be a sufficient colony formed of the outcasts and miscreants of our own nation to take it up. Much do we fear that neither Dr. Edwards, nor any other Doctor, can so far regenerate the world, or the smallest civilized part of it, as to carry these resolutions into any permanent effect; and how feebly such associations operate we all know from the association of the Americans not to drink any tea till they could drink it unstampt: they substituted the leaf of every green herb and tree in their united provinces, till they could drink them no longer, and then smuggled-in foreign tea from British markets in the vessels of other nations of Europe. Such are

* Epistle to William Wilberforce, Esq. on the Rejection of the Bill for abolishing the SlaveTrade. By Anna-Letitia Barbauld.An Address to every Briton on the Slave-Trade, being an effectual Plan to abolish this Disgrace to our Country (reviewed in p. 944).Elegy occasioned by the Rejection of Mr. Wilberforces Motion (reviewed in p. 358). See An Address to the People of Great Britain on the Consumption of West Indian Produce. 219

Copyright

220

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7

patriotic associations!!! Much, alas! do we fear that there will be found too many backsliders amongst the Friends, strictly so called, who, with all their abhorrence of the slave-trade, would purchase West Indian sugar, and sell it for East Indian, and at an advanced price. Philosophic and truly patriotic minds, and, indeed, men of the commonest understandings, would see that such a measure as the abolition of the slave-trade demands the coolest and most mature deliberation, and cannot possibly be carried into execution hastily. Reforms in the conduct of it are for the interest both of trade and humanity. Resolutions, such as the abolishers clamour for, would only involve half the West Indies in insurrection and bloodshed. Instead of doing evil that good may come of it, we should do good and produce evil. Most earnestly should we pray that no Abb Gregoire may carry his sentiments into execution in this country; sentiments which have made one of the most flourishing colonies of his own country a scene of devastation sufficient to teach every unprejudiced mind what we have to expect from the savages of Africa. But such is the inconsistency of the human mind, that there are persons, of good understanding, who, while justified by experience in thinking the Dissenters are not to be admitted to places of power and trust, would admit these savages to the rights and powers of civilized nations.

Copyright

The slave-trade (say the Monthly Reviewers for October last) is now an old subject: but these Reflections are the dictates of a worthy heart, which estimates all other hearts according to a consciousness of its own integrity. The author considers the trade in slaves as a moral evil, a religious evil, and a political one: it is certainly all three; and we are sorry to add, that it is one of those evils which the mass of mankind never were, and in all probability never will be, sufficiently enlightened to eradicate. We think our author often mistaken in arguing from right to fact: thus he declares, I cannot conceive that it ever was the intention of the Creator of the world to place his creatures in a state where their very existence must depend solely upon mutual [1125] violence, rapine, and destruction.

Yet are they not actually so placed over a great part of the globe, where civilization, and the establishment of wholesome laws, have not altered their condition? Again:

Is the African a member of society, or is he not? The advocates for the slave-trade contend, that he is still in a state of nature, an unsociated savage. I contend, on the contrary, that he is a member of society, and as such entitled to the benefit of civil institutions, to liberty, and to security.

We scarcely understand what it is for which the author contends in this passage. Bring the Africans here, and he will be entitled to the civil institutions in force here: but at home he enjoys all to which he is entitled, according to the usages that prevail in his own country; and they appear to be what the author declares to be contrary to the intentions of his Creator; wanton butchery, or sale into captivity, from neither of which it is in our power to release him, notwithstanding this writer adds, that the benefits of society were never intended to be

Gentlemans Magazine

221

confined within the narrow limits of countries, but to extend over the face of the globe, the equal right of all mankind. They are evidently intended to extend so far as they take place. Happy would it be, if we could carry into universal execution all the moral, religious, and political principles here laid down, which every considerate man will agree to be necessary to the perfection of civil society; and did the accomplishment of such a grand scheme of universal philanthropy rest with us, the reproach of employing slaves would not long exist:--but while we may lament that the one half of mankind neither understand, nor would assent to, moral, religious, and political truths, if propounded to them, our intercourse with other nations must be regulated according to their notions of things. Even in lands where we have gained some ascendancy, as in the East, we find it an indispensable obligation to accommodate our maxims of conduct to the ideas and habits of the people. When another nation determines to go to war with us, they oblige us to cut the throats of as many of them as we can, to save our own; and, not to shrink from the direct subject, it is nugatory to investigate the motives of Negro wars, or to deny their right to sell their captives; and we cannot but smile to find this author gravely censure their practices, by quotations from Montesquieu and Blackstone! All that we have to do is to convert evil to good, as far as we are able, in our concerns with them. Totally to renounce all dealings with them, is doing no good to the objects of our compassion, but infinite injury to ourselves. We must, in this case, quit abstract reasoning, and act so as to support our rank among the rival nations by whom we are surrounded, and who will instantly seize every advantage which we neglect; and, if we use our slaves well, it is a real kindness to purchase them out of worse hands. What begins in slavery, then, will soon relax into common service for common protection. How men reason in their closets will appear in the following extract:

The African, I suppose, is as sensible of the blessings and advantages of peace, and of the horrors and devastations of war, as the most civilized European. And as harmony seems more natural to the human frame than discord, I conclude that the African, partaking of the same nature as the European, has the same inclinations and propensity to the one, as dislike and aversion to the other. Perhaps I am led to this opinion rather by the dictates of my own heart than a strict adherence to fact; but, whatever may be the dispositions of individuals, however sanguinary the minds of some members of every community are, I can scarcely conceive that any body of men, collected into a compact of government, and actuated by the first and most natural of all impulses, the desire of happiness, will prefer a system of everlasting rapine and plunder to the contrary one of perennial peace, harmony, and good order*. I speak not now of those fierce and numerous bodies of banditti who infest the wild deserts of Arabia, and bid defiance to the civil power. I speak not of those hordes or tribes of wandering Indians, who, like the old Patriarchs, live in caves and deserts, upon the roots of the earth. I * Is it possible this writer can have Africa in his eye, under so poetical a description!

Copyright

222

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7 speak of large and populous nations, of extensive and numerous communities, who are bound by systems of laws, rules of policy, which we have no reason to ridicule and despise. Whence then the perpetual scene of war and desolation that fills the states of Africa with blood? From what cause, from what source, does it originate? It originates not from the dispositions of the natives; not from the situation and proximity of the respective states; not from the manners and customs, the policy and religion, of the country. It originates in the instigations of wicked and profligate men, from the rewards that are offered, from the gilded bait that is hung out and eagerly taken by those deluded wretches. The kings or chieftains of each principality are bribed to attack, plunder, and carry away each others subjects. Here then lies the onus of guilt: the captains of the slave-ships are the primary cause of that perpetual scene of desolation, rapine, and violence, which, contrary to the nature of things, to the pacific disposition of the natives, to Religion, Justice, and Humanity, is kept alive with unabated ardour on the coat of Africa. [1125] Had this writer deemed it necessary to inquire minutely into the interior state of Africa, before he wrote, he would perhaps have quitted the subject. So far as we can rely on concurring information, the case is far different from what is here represented. The European slave-ships compose but a small potion of the chapmen; the great trade for slaves is with the Moors of Barbary, and with the Asiatic powers, particularly the Turks*, by a current inland traffick that does not come under our observation. The scheme here proposed, of superseding the use of black slaves, by transferring our convicts from Botany Bay to the sugar-islands, is not more mature than this view of the slave-trade. Supposing we had a sufficiency (which God forbid!) to furnish them with a full supply of desperadoes, could so many thousands of men, versed in Eropean arts, and void of all principle, be harboured with as little hazard as the same number of less corrupt Negroes? or must the islands be encumbered with a suitable military force to guard them? These islands are depraved enough at present; and what moral, religious, or political consequences would arise from an influx of such reformers, may be left to our authors future thoughts on the subject. [1126]

Copyright

Bec-de Lievre, Madame de Bentley, Elizabeth

61:2 no. 2 (August), p. 747. 121. Genuine Poetical Compositions. By E. Bentley, of Norwich.

E-Po. 61:2 (Supplement), p. 1222. Elegy on the Death of John Howard, Esq. at Cherson, Jan. 20, 1790.1 By Madame la Comtesse de Bec-DeLievre.

Noa more, my pipe, rehearse your sylvan plaint! [] Live Howards soul, in some new form to burn!

This is certainly an extraordinary performance. The authoress is a poor, uneducated daughter of a journeyman shoemaker, who, without any assistance from

* The numerous Eastern harams are usually guarded by black eunuchs.

Gentlemans Magazine

223

books, or even the opportunity of improvement from conversation, has exhibited strong marks of a polished and superior mind. The present is with equal truth and energy called the Age of Benevolence; and we are very happy to find that the humble merit of Mrs. Bentley has excited the interest, and obtained the patronage, of an opulent manufacturing town. Her early talent for poetical composition has been eagerly encouraged and generously rewarded, as a long list of subscribers sufficiently testifies. When we say of her poems, that they are always correct, frequently animated, and often above mediocrity, we hope that many of our readers will be induced to contribute to the purpose the authoress has in view, of printing a second edition. To strengthen such a propensity, it gives us pleasure to add, that the emoluments of the present and future publications are designed for the support and comfort of an aged and infirm parent. The following is subjoined as a specimen of her abilities:

Ode to Chearfulness. May, 1790. Hail! Virgin of therial birth, Thou more lovely far than Mirth, O hither bend thy way! Come, beauteous Nymph, serenely smiling, Evry anxious thought beguiling, Thou makst each prospect gay. Thine eye with joy young Spring beholds, When Nature evry charm unfolds, And spreads thy favrite hue; When Eurus to his cave retires, And Zephyr fans those glowing fires That verdant life renew. Thou lovst to range the fields at dawn, Or meet the shepherds on the lawn, At leisure Eves advance; Brisk Sport comes tripping oer the mead, And sweetly sounds his oaten reed, And joins the rural dance. Not een hoar Winters dreary sway, Nor freezing blast can thee dismay, Nor change thy sprightly mien; Tis then thou seekst the social band, And oer their minds, with gentle hand, Diffusst a joy serene. Though absent Sol his ray denies, Round the bright flame which Art supplies, The friendly train regale; Some fairy legend each imparts,

Copyright

224

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7 Whilst rapt Attention, gazing, starts At evry wondrous tale. Thy presence charms stern Grief to rest, Thy light illumes th untainted breast, Sweet sister of Content; Like her thou flyst th abandond mind, Where Guilt, Despair, and Shame, combind, Their hapless prey torment. What magick in thy aspect dwells! That Melancholys mist dispells; What graces round thee shine! Sweet Pleasure ever near thee stands, With Transport, whose high soul expands, And soars to realms divine.

Brooke, Frances

T. 61.1 no. 5 (May), p. 495. Theatrical Register.

Copyright

Centlivre, Susanna

T. 61:1 no. 1 ( January), p. 86. Theatrical Register. T. 61:1 no. 4 (April), p. 363. Theatrical Register. T. 61:1 no. 6 ( June), p. 591. Theatrical Register. T. 61:2 no. 3 (September), p. 879. Theatrical Register.

May 12 and 27. Covent-Garden. Rosina [Performed with Wild Oats (12 May) and both Lovers Quarrels and Comus (27 May).]

Jan. 1. Covent-Garden. The Busy Body [Performed with The Picture of Paris.]

April 4. Drury-Lane. The Gamester [Performed with The Deuce is in Him.]

June 14. Covent-Garden. The Busy Body [Performed with The Farmer.]

Sept. 17. Covent-Garden. The Busy Body [Performed with Love in a Camp.]

Gentlemans Magazine

225

T. 61.2 no. 5 (November), p. 1071. Theatrical Register. Nov. 29. Drury-Lane (Hay-Market). The Wonder [Performed with Richard Coeur de Lion.]

Corinna

Ref. See Inchbald, Elizabeth, 61:1 no. 3 (March), p. 255.

Cowley, Hannah

T. 61:1 no. 3 (March), p. 287. Theatrical Register. Feb. 15. Drury-Lane. Whos the Dupe? [Performed with The Siege of Belgrade.] T. 61:1 no. 3 (March), p. 287. Theatrical Register. Feb. 15 and 21. Covent-Garden. The Belles Stratagem [Performed with The Farmer (15 February) and Two Strings to Your Bow (21 February).] T. 61:1 no. 4 (April), p. 363. Theatrical Register.

April 30. Drury-Lane. Whos the Dupe? [Performed with The Haunted Tower.] T. 61:1 no. 5 (May), p. 495. Theatrical Register.

Copyright

May 10 and 26. Drury-Lane. The Belles Stratagem [Performed with Follies of a Day (10 May) and The Padlock (26 May).] May 31. Covent-Garden. The Runaway [Performed with The Liar.] T. 61.1 no. 5 (May), p. 495. Theatrical Register. May 24. Covent-Garden. Which is the Man? [Performed with Primrose Green.] T. 61:1 no. 6 ( June), p. 591. Theatrical Register. June 3. Covent-Garden. The Belles Stratagem [Performed with The Cottage Maid.]

226

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7

T. 61:1 no. 6 ( June), p. 591. Theatrical Register. June 8. Hay-Market. Whos the Dupe? [Performed with The Battle of Hexham.] T. 61:2 no. 2 (August), p. 783. Theatrical Review. Aug. 26. Hay-Market. Whos the Dupe? [Performed with both The Battle of Hexham and The Catch Club.] T. 61:2 no. 3 (September), p. 879. Theatrical Register. Sept. 12 and 15. Hay-Market (Little). Whos the Dupe? [Performed with The Surrender of Calais.] T. 61:2 no. 4 (October), p. 975. Theatrical Register.

Copyright

T. 61:2 no. 6 (December), p. 1167. Theatrical Register. 61:2 no. 6 (December), p. 1118. Mr. Urban, Sawbridgeworth, Dec. 10.

, , All things of nothing sprang, from dust or smoke, Devoid of reason all things all a joke! Yours, &c. John Lane.

Oct. 24. Drury (Hay-Market). Whos the Dupe? [Performed with The Siege of Belgrade.]

Dec. 3, 5, 6, 9, and 30. Covent-Garden. A Day in Turkey; or, The Russian Slaves [Performed with Hob in the Well (3 December), Oscar and Malvina (5 December), The Farmer (6 December), A Divertisement (9 December), and Blue Beard; or, The Flight of Harlequin (30 December).]

Should you judge the following extempore translation of the old Greek epigram (which Mrs. Cowley has introduced in her farce Whos the Dupe?) not unworthy your entertaining Miscellany, I will beg you to insert it

Gentlemans Magazine

227

Clanranald, Lady

61:1 no. 1 ( January), pp. 55-7. 7. Memoirs of the Life and gallant Exploits of the old Highlander, Serjeant Donald Macleod, who, having returned, wounded, with the Corpse of General Wolfe, from Quebec, was admitted an Out-pensioner of Chelsea Hospital in 1759; and is now in the 103d Year of his Age. Several anecdotes of this interesting character have appeared in the public papers; and a very general curiosity has been excited to enquire farther into the life, fortune, and character of a man who has survived so many hardships and wounds, and still, in the 103d year of his age, enjoys a viridis senectus in an uncommon and an astonishing degree. This curiosity the Memoirs now presented to the publick are calculated fully to gratify; while they serve, at the same time, to paint, in some degree, the different stages and scenes of that long period and busy drama in which the gallant serjeant acted a distinguished part. They are drawn-up by a person who possesses an easy style and humour, and is conversant in British history and general knowledge. Donald Macleod, we are informed by his biographer, in the outset,

a cadet of the family of Ulinish, in the Isle of Skye, from the time of his enlisting in the Scotish army, in the reign of King William, to his last campaign with Sir Henry Clinton in America, sent hundreds of heroes to their long homes: but, in return, he raised up, from his own loins, a numerous race of brave warriors, the eldest of whom is now eighty-three years old, and the youngest only nine. Nor, in all probability, would this lad close the rear of his immediate progeny, if his present wife, the boys mother, had not now attained to the forty-ninth year of her age.

Copyright

Our biographer, after this exordium, makes some observations on feudal customs and manners, tending to shew how soon the descendants of lairds, or men of landed property, very often were mingled with the common people; when estates were parceled out among a number of children, or let in different lots, to younger brothers, at easy rents, under the name of tacksmen; and these, again, sub-let, in smaller divisions, to their offspring; when men of family had not the same resources in manufactures and trade that they have now, and which, if they had enjoyed, they would have despised:--it ought not, therefore, to seem any ways incredible, that Serjeant Donald Macleod is, by his mother, a grandson of Sir Roderick Macdonald, of Slate, and, by his father, a grandson of Macleod of Ulinish; the representative of which family, we are informed, is at present sheriff of a district of Invernessshire, and turned of 100 years. Donald Macleod was brought-up in a manner so hardy as scarcely to appear credible, and, after learning to read and write, was bound apprentice to a stone-cutter in Inverness; from whom he made his escape, and enlisted, not yet 13 years of age, in the

228

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7

Scots Royals, commanded by the Earl of Orkney, at Perth, in 1703. He went abroad the same year, and served in Germany and Flanders, under the Duke of Marlborough. Returning home, he was severely wounded at the battle of the Sheriffmuir, in 1715. He left the Scots Royals by permission, and entered into the independent companies of the Highland Watch, raised for keeping the peace in the Highlands, and enforcing the laws among a rude and untractable people. Here we shall give an extract that may serve as a specimen of the entertaining performance before us.

Our late Serjeant in Captain Macdonalds company, in the Scots Royals, was now all impatience to revisit the environs of Inverness, from which, about twelve years ago, he had fled, and to offer his services to Lord Lovat, who had married a daughter of Macleod of Dunvegan, the chief of his clan. At three oclock, on a summers morning, he set out, on foot, from Edinburgh, and, about the same hour, on the second day thereafter, he stood on the green of Castle Downie, Lord Lovats residence, about five or six miles beyond Inverness; having performed, in 48 hours, a journey of an hundred miles and upwards, and the greater part of it through a mountainous country. His sustenance on this march was bread and cheese, with an onion, all which he carried in his pocket, and a dram of whiskey at each of the great stages on the road, as Falkland, the half-way-house between Edinburgh, by the way of Kinghorn and Perth; the town [55] of Perth (where he did not fail to call on Mary Forbes, to whom he made a present, and his former master, James Macdonald); Dunkeld, Blair, Dalwhinnie, Ruthven of Badenoch, Avemore in Strathspey, and, perhaps, one or two other places. It is to be understood, that what is here called a dram of whiskey was just half a pint; which, it may be farther mentioned, he took pure and unmixed. He never went to bed during the whole of this journey; though he slept, once or twice, for an hour or two together, in the open air, on the road-side. By the time he arrived at Lord Lovats park, the sun had risen upwards of an hour, and shone pleasantly, according to the remark of our hero, well pleased to find himself in this spot, on the walls of Castle Downie, and those of the antient abbey of Beaulieu in the near neighbourhood. Between the hours of five and six, Lord Lovat appeared, walking about in his hall, in a morning-dress; and at the same time a servant flung open the great folding doors, and all the outer doors and windows of the house. It is about this time that many of the great families in London, of the present day, go to bed. As Macleod walked up and down on the lawn before the house, he was soon observed by Lord Lovat, who immediately went out, and, bowing to the Serjeant with great courtesy, invited him to come in. Lovat was a fine-looking, tall man, and had something very insinuating in his manners and address. He lived in all the fulness and dignity of the antient hospitality, being more solicitous, according to the genius of feudal times, to retain and multiply adherents than to accumulate wealth by the improvement of his estate. As scarcely any fortune, and certainly not his fortune, was adequate to the extent of his views, he was obliged to regulate his unbounded hospitality by rules of prudent conomy. As his spacious hall was crowded by kindred visitors, neighbours, vassals, and tenants of all ranks, the table, that extended from one end of it nearly to the other, was covered, at different places, with different kinds of meat and drink; though of each kind there was always great abundance. At the head of the table, the lords and lairds pledged his lordship in claret, and some-

Copyright

Gentlemans Magazine times in champagne; the tacksmen, or duniwassals, drank port, or whiskey punch; tenants, or common husbandmen, refreshed themselves with strong beer; and below the utmost extent of the table, at the door, and sometimes without the door of the hall, you might see a multitude of Frazers, without shoes or bonnets, regaling themselves with bread and onions, with a little cheese perhaps, and small-beer. Yet, amidst the whole of this aristocratical inequality, Lord Lovat had the address to keep all his guests in perfectly good humour. Cousin, he would say to such and such a tacksman, or duniwassal, I told my pantry lads to hand you some claret, but they tell me ye like port and punch best. In like manner, to the beer-drinkers he would say, Gentlemen, there is what ye please at your service; but I send you ale, because I understand ye like ale best. Every body was thus well pleased; and none were so ill-bred as to gainsay what had been reported to his Lordship. Donald Macleod made his compliments to Lovat in a military air and manner, which confirmed and heightened that prepossession in his favour which he had conceived from his appearance. I know, said he, without your telling me, that you have come to enlist in the Highland Watch. For a thousand such men as you I would give my estate. Macleod acknowledged the justice of his Lordships presentiment; and, at his request, briefly related his pedigree and history. Lovat clasped him in his arms, and kissed him; and, holding him by the hand, led him into an adjoining bed-chamber, in which Lady Lovat, a daughter of the family of Macleod, lay. He said to his lady, My dear, here is a gentleman of your own name and blood, who has given up a commission in Lord Orkneys regiment, in order to serve under me. Lady Lovat raised herself on her bed, congratulated his Lordship on so valuable an acquisition, called for a bottle of brandy, and drank prosperity to Lord Lovat, the Highland Watch, and Donald Macleod. It is superfluous to say, that in this toast the lady was pledged by the gentlemen. Such were the customs and manners of the highlands of Scotland in those times. By the time they returned to the hall, they found the laird of Clanronald, who, having heard Macleods history, said, Lovat, if you do not take care of this man, you ought to be d---. His Lordship immediately bestowed on him the same rank, with somewhat more pay, than he had received in the Royal Scots; and, after a few days, sent him on the business of recruiting. Macleod, from the time that he went to the shires of Inverness and Ross, to recruit for Lord Orkney, passed under the name of the name that was lost and found. The time that he served in the Highland, now called the 42d regiment, so long as it was stationed in the mountains of Scotland, a period of about twenty years, was filled up in a manner very agreeable to the taste of our hero; in training-up new soldiers (for he was now employed in the lucrative department of a drill-serjeant); in the use of the broad sword, hunting after incorrigible robbers, shooting, hawking, fishing, drinking, dancing, and toying, as heroes of all times and countries are apt to do, with the young women.

229

Copyright

The independent highland companies were incorporated, about 1740, into a regiment, under the name of the 42d, [56] and sent abroad to join the army under the Duke of Cumberland. In 1745, when the body of the army marched Northwards against the rebels, the Highlanders, suspected by Government, were sent to Ireland. From Ireland, in 1758, they were sent to America, where Macleod was drafted from the 42d to act as a drill-serjeant in the 78th, or Frasers

230

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7

Copyright

Craven, Elizabeth, Lady

Ref. 61:2 no. 4 (October), pp. 97071. Obituary of considerable Persons; with Biographical Anecdotes.

Highlanders. Wounded in the battle of Quebec, he came home in the ship that carried the corpse of Gen. Wolfe, in 1759, and was admitted an out-pensioner of Chelsea Hospital: yet such was the spirit of this hardy veteran, that he went recruiting for the Colonels Campbell and Keith, in the Highlands, in 1760, and served under them voluntarily, in the rank of a paymaster-serjeant, in 1761, in Germany. After the peace, he resided sometimes at Inverness, sometimes at Chelsea, pursuing various occupations: but, on the breaking-out of the American war, as war was his very element, he went abroad, though near ninety years of age, and offered his services to Sir Henry Clinton, who had known him in Germany, then commanding the British forces at Charlestown. Sir Henry received him kindly, and allowed him half a guinea-a-week out of his own pocket: but, when the army was about to move Northwards, unwilling to subject the old Serjeant to the fatigues of the campaign, he sent him home in a frigate that carried dispatches to Government. Our bounds will not permit us to follow this biographer into the details he gives of Mr. Macleods exploits in war, his enterprizes, his duels, his wounds, his hair-breadth scapes; nor into his manner of life, into which our author has, with great propriety, enquired very minutely. But we cannot avoid mentioning, that Macleod, in his prime, did not exceed five feet seven inches, and that he is now inclined, by age, to five feet five inches; that he has still exceedingly high spirits, hates to be long in bed, and loves to be in motion; and that he has a very fine physiognomy, expressive of sincerity, sensibility, and determined courage. We entirely agree with the author of the Memoirs, that he would be a very fit subject for the Polygraphic Society, who, by multiplying his likeness, at an easy rate, might gratify a very general curiosity, and furnish new matter of reflexion to the speculators in physiognomy. [57]

At Lausanne, in his 53d year, Right Hon. William Lord Craven, Baron of Hamstead Marshall, lord lieutenant and custos rotulorum2 of the county of Berks, colonel of the Berkshire militia, recorder of Newbury, &c. His Lordship was born Sept. 22, 1737, and succeeded his uncle, the late Lord, in 1769. He married, 1767, Elizabeth, daughter of the late, and sister of the present, Earl of Berkeley; of his separation from whom, and her subsequent Travels with the Margrave of Anspach, see our vol. LX. p. 237. [970]

Gentlemans Magazine

231

Doddridge, Mercy

61:1 no. 2 (February), pp. 1278. Mr. Urban, Feb. 2. P. S. Mrs. D. whose death you recorded in vol. LX. p. 377, was Mercy Maris, a native of Worcestershire, married to the Doctor in Dec. 1730. She brought him one son, who is an attorney at law, and three daughters. The eldest married to Mr. Humphreys, attorney at Tewksbury; the two others single, 1766. [128] Ref. 61:2 no. 4 (October), pp. 8835. Mr. Urban, Oct. 11. I greatly admire the present respectable Bishop of Durhams Speech to his Chapter, which you have given in p. 695. It bespeaks the elegant scholar, the polite nobleman, and, what is above all, the serious Christian prelate. Friendly as I am to our present [883] excellent Church-establishment, I greatly respect many of the Dissenters and their writings, such as Dr. Doddridge and Mr. Orton, who are both dead, and whose letters and correspondence I would strongly recommend to the publick. And I should have thought more favourably of Dr. Price if he had died in those tenets which he professed in his sermon of 1759; extracts from which are to be had at Mess. Rivingtons. Mr. John Claytons Address and Sermon of the present day do him much credit; and, if the same rational, moderate, and candid spirit, had influenced the rest of his brethren, we should neither have heard of Birmingham riots, nor of the French Revolution-feasts in England. The widow of that excellent man, Dr. Doddridge, died within these two years. It is to be hoped that the Editor of his Correspondence, in the next edition, will insert the admirable and pious letter which she wrote to her children, from Lisbon, upon the death of their father. In the mean time, I send it to you, to insert in your useful and interesting Repository. Philip Doddridge, D.D. was prevailed upon, for the recovery of his health, to go to Lisbon, in the neighbourhood of which city he died October 26, 1751. His Widow, Mrs. Mercy Doddridge, who accompanied him thither, wrote the following letter to her children in England after his decease. Yours, &c. O. C.

My dear Children, Lisbon, Nov. 11, N.S. 1751. How shall I address you under this aweful and melancholy Providence! I would fain say something to comfort you. And I hope God will enable me to say something that may alleviate your deep distress. I went out in a firm dependence that, if Infinite Wisdom was pleased to call me out to duties and trials as yet unknown, He would grant

Copyright

232

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7 me those superior aids of strength that would support and keep me from fainting under them; persuaded that there was no distress or sorrow, into which he could lead me, under which his gracious and all-sufficient arm could not support me. He has not disappointed me, nor suffered the heart and eyes directed to him to fail. God all sufficient, and my only hope, is my motto: let it be yours. Such, indeed, have I found him; and such, I verily believe, you will find him too in this time of deep distress. Oh! my dear children, help me to praise Him! such supports, such consolations, such comforts, has He granted to the meanest of His creatures, that my mind, at times, is held in perfect astonishment, and is ready to burst into songs of praise under its most exquisite distress. As to outward comforts, God has withheld no good thing from me, but has given me all the assistance, and all the supports, that the tenderest friendship was capable of affording me, and which I think my dear Northampton friends could not have exceeded. Their prayers are not lost. I doubt not but I am reaping the benefit of them, and hope that you will do the same. I am returned to good Mr. Kings. Be good to poor Mrs. King. It is a debt of gratitude I owe for the great obligations I am under to that worthy family here. Such a solicitude of friendship was surely hardly ever known as I meet with here. I have the offers of friendship more than I can employ; and it gives a real concern to many here that they cannot find out a way to serve me. These are great honours conferred on the dear deceased, and great comforts to me. It is impossible to say how much these mercies are endeared to me, as coming in such an immediate manner from the Divine Hand. To his name be the praise and glory of all! And now, my dear children, what shall I say to you? Ours is no common loss. I mourn the best of husbands and of friends, removed from this world of sin and sorrow to the regions of immortal bliss and light. What a glory! What a mercy is it that I am enabled with my thoughts to pursue him there! You have lost the dearest and best of parents, the guide of your youth! and whose pleasure it would have been to have introduced you into life with great advantages. Our loss is great indeed! But I really think the loss the publick has sustained is still greater. But God can never want instruments to carry on his work. Yet, let us be thankful that God ever gave us such a friend; that he has continued him so long with us. Perhaps, if we had been to have judged, we should have thought that we nor the world could never less have spared him than at the present time. But I see the hand of Heaven, the appointment of His wise providence in the every step of this aweful dispensation. It is his hand that has put the bitter cup into ours. And what does he now expect from us but a meek, humble, entire submission to his will? We know this is our duty. Let us pray for those aids of His Spirit, which can only enable us to attain it. A father of the fatherless is God in his holy habitation. As such may your eyes be directed to him! He will support you. He will comfort you. And that he may is not only my daily, but hourly, prayer. We have never deserved so great a good as that we have lost. And let us remember, that the best respect we can pay to his memory is to endeavour, as far as we can, to follow his example, to cultivate those amiable qualities that rendered him so justly dear to [884] us, and so greatly esteemed by the world. Particularly I would recommend this to my dear P. May I have the joy to see him acting the part worthy the relation to so amiable and excellent a parent, whose memory, I hope, will ever be valuable and sacred to him and to us all! Under God, may he be a comfort to me, and a support to

Copyright

Gentlemans Magazine the family! Much depends on him. His loss I think peculiarly great. But I know an all-sufficient God can over-rule it as the means of the greatest good to him. It is impossible for me to tell you how tenderly my heart feels for you all! how much I long to be with you to comfort and assist you! Indeed, you are the only inducements I have left to wish for life that I may do what little is in my power to form and guide your tender years. For this purpose I take all possible care of my hearth. I eat, sleep, and converse at times with a tolerable degree of chearfulness. You, my dears, as the best return you can make me, will do the same, that I may not have sorrow upon sorrow. The many kind friends you have around you, I am sure, will not be wanting in giving you all the assistance and comfort that is in their power. My kindest salutations attend them all. I hope to leave this place in about fourteen or twenty days. But the soonest I can reach Northampton will not be in less than six weeks, or two months time. May God be with you, and give us, though a mournful, yet a comfortable meeting! for your sakes I trust my life will be spared. And, I bless God, my mind is under no painful anxiety as to the difficulties and dangers of the voyage. The winds and the waves are in His hands, to whom I resign myself, and all that is dearest to me. I know I shall have your prayers, and those of my dearest friends with you. Farewell, my dearest children! I am your afflicted, but most sincere friend, and ever affectionate mother, M. Doddridge. [885]

233

Ref. See Tyrwhitt, Elizabeth, 61:1 no. 1 ( January), pp. 279.

Copyright

Elizabeth I, Queen of England Graham, Catharine Macaulay

B. 61:1 no. 6 ( June), pp. 58990. Obituary of considerable Persons; with Biographical Anecdotes. 23. At Binfield, Berks, after a long and very painful illness, Mrs. Catherine Macaulay Graham. She was the youngest daughter of John Sawbridge, esq. of Ollantigh, Kent, and sister of John S. esq. alderman of London. June 13, 1760, she married George Macaulay, M. D. (see his writings in the Medical Observations of the London Physical Society, in our vol. XXVII, pp. 224, 362); who died in 17.., leaving by her one daughter, married, Dec. 7, 1787, to Cha. Gregory, esq. an East India captain. Mrs. M. re-married, Dec. 17, 1778, the younger brother of the celebrated Dr. Graham, with whom she retired to a cottage in Leicestershire. She began her literary career with the History of England, from James I. to the Brunswick Line; the first volume of which was published in 1763; the second, 1765; the third, 1767; the fourth, 1769; the fifth, 1771; the sixth and seventh, 1781; and the eighth, 1783. Thoughts on the Causes of the present Discontents, 1770 (see our vol. XL. p. 222). A modest Plea for the Property [589] of Copy-right (XLIV. 125). History of England, from the Revolution to the pre-

234

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7

sent Time; in a Series of Letters to a Friend, the Rev. Dr. Wilson, Prebendary of Westminster, 1778, 4to. (XLVIII. 528); on which C. Lofft, esq. published Panegyrical Observations the same year. A Treatise on the Immutability of Moral Truth, 1783, 8vo. An Address to the People of England, Scotland, and Ireland, on the present important Crisis of Affairs, 1775, 8vo. Her last publication was, Letters on Education, 1790, 8vo. The enthusiastic devotion paid to her, as a favourer of Liberty, by the late Dr. Wilson, prebendary of Westminster, by setting up a statue of her, in the character of the Goddess of Liberty, in her life-time, in the chancel of his church in Walbrook, which on his death was removed, is well known. I looked to no purpose, says Mr. Pennant, in his History of London, p. 388, for the statue erected divae macaviae, by her doating admirer, a former rector, which a successor of his has most profanely pulled down. [590] Ref. 61:2 no. 1 ( July), p. 618. Mr. Urban, July 2. You will please to correct an error in your Obituary for the last month, p. 590, concerning the monument erected in Wallbrook church for Mrs. Macaulay. It was taken down (by the statuary who erected it) in the life-time of Dr. Wilson, and by his order. Whether the Doctor was instigated so to do from motives of revenge, because she married Mr. Graham, or whether from fear, because the Vestry was just upon citing him to the Commons for it, I will not undertake to say; perhaps from both; for, very soon after, he sold the vault, which he built to deposit her remains in, to a branch of the Royds, a wealthy and respectable family in that parish; so that it was her doating admirer, then rector, not his successor, most profanely (if Mr. Pennant will have it so) pulled it down. Whatever idea Mr. Pennant may have of this transaction, the inhabitants of the parish thought the church was not a proper place for enthusiastic Party and politicks, and was determined to carry the matter into the Ecclesiastical Court, if the Doctor had not thought proper to have it taken down almost as suddenly as it was put up. The present incumbent, who was his successor, did not, nor could he, take any steps whatever about this business. A. Y. Z. Ref. See Wollstonecraft, Mary, 61:2 no. 1 ( July), pp. 6545.

Copyright

Gunning, Elizabeth

Ref. See Gunning, Susannah, below.

Gentlemans Magazine

235

Gunning, Susannah

61:1 no. 2 (February), p. 180. Fashionable Mystery. About two years ago, the M of B met the accomplished Miss G at a ball, and had the good fortune to engage the ladys hand as his partner for the evening. Soon after, Miss G received a letter from the M as she believed, expressing very tender sentiments of admiration, and soliciting permission to visit and to correspond with her. The rank and pretensions of the M were indisputable recommendations of his suit; and a correspondence was begun, which General G was not indisposed to countenance, as he was informed that the D his father was perfectly acquainted with his sons attachment. The correspondence went on for some months, until the Dof A suggested some doubts of the D of Ms being acquainted with the affair. General G wrote a letter to the Noble D, communicating the penchant of the son, and saying, that unless it was with his Graces perfect consent, he would not suffer the correspondence to go on. That this letter might be conveyed with becoming attention, the General dispatched his own servant with it; and after a proper interval he received, by the hand of the same messenger, an answer from the D, assuring the General of his perfect respect for the young Lady, to whose merits he was no stranger; and that an alliance with the ancient family of the General would be highly desirable to every branch of his House. The envelope had the Noble Dukes seal of arms. This, for the time, satisfied the scruples of the D of A; and now that all cause of secrecy was removed, it was expected that the M would avow his passion, and publickly visit Miss G. They waited in vain for this event; and wondering at his absence, the D of A shewed the letter, which the General had received, to L C S, desirous of knowing if it was his Noble Brothers writing and seal. Lord C said it was a clumsy forgery of the Ds hand; but that the seal was either a copy of, or the actual seal which the D had worn to his watch about five years ago, but had not used it since, as he had now a seal of a smaller size and different form. The General, shocked with this information, questioned Mrs. and Miss G; told them that a forgery had been practiced either by or on them; and, with the authority of a husband and farther, demanded the truth. He received no other answer, than that they were equally dupes of the fraud, if it was a fraud. He flew to the servant whom he had entrusted with this letter; and, having made him properly to apprehend the effects of his fury if he deceived him, he drew from him a disclosure of the whole plot, that the D was utterly ignorant of the whole affair; and that the M had never shewn any other than the attentions of common politeness to the Lady. The General, on this exposure, took the

Copyright

236

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7

Copyright

61:2 no. 3 (September), p. 856. The For Lorn Maiden.

measure of a man more jealous of honour, than softened by parent weakness. He gave his wife and daughter twenty-four hours to justify their conduct; at the end of which if they failed to acquit themselves, they must leave his house for ever. They immediately withdrew, and took shelter under the protecting kindness of the Duchess of Bd. Such is the vague story, and which we have willingly submitted to relate, absurd as it is, because the ladies are not unwilling that the gross fiction, which has produced such serious consequences to them, should go forth; its own improbability being its refutation. Here is a stratagem without a motive, and a forgery working to no benefit. The M could not be drawn into marriage by a correspondence of which he was ignorant; and it surely was not a very likely means for the young Lady to engage the heart of any other Nobleman, by pretending to be violently enamoured herself of another her letters are made to breathe the warmest and most tender affection for him. The fact is, that, deep, dark, and mysterious as the plot has been, it will turn out to be an artful machine in a quarter from which the young Lady should rather have received protection than injury; practiced for the purpose of drawing off the affections of a young Nobleman really enamoured of her charms, and to whose passion they were adverse. Miss G was, equally with her mother, the dupe of the contrivance; and unless gallantry shall rouse gentlemen to inquire before they decide, she may become the victim! Mrs. G and Miss G have both made affidavit, that the letters of the pretended correspondence, the scandalous story of which we have exhibited so circumstantially, were not written by them, or with their privity.

This is the note, that nobody wrote. This is the groom, that carried the note, that nobody wrote. This is Maam Gunning, who was so very cunning, as to betray the groom, that carried the note, that nobody wrote. This is Maam Bowing, to whom it was owing, that Mrs. Minifie Gunning was so very cunning, as to betray the groom, that carried the note, that nobody wrote. This is the maiden all for Lorn, to become of a sudden so tatterd and torn, by means of Maam Bowing, to whom it was owing, that Mrs. Minifie Gunning was so very cunning, as to betray the groom, that carried the note, that nobody wrote. These are the Marquisses, shy of the horn, that caused the maiden all for Lorn, to become of a sudden so tatterd and torn, by means of Maam Bowing, to

Gentlemans Magazine

237

whom it is owing, that Mrs. Minifie Gunning was so very cunning, as to betray the groom, that carried the note, that nobody wrote. These are the two Dukes, whose bitter rebukes made the two Marquisses shy of the horn, and the maiden all for Lorn, to become of a sudden so tatterd and torn, by means of Maam Bowing, to whom it was owing, that Mrs. Minifie Gunning was so very cunning, as to betray the groom, that carried the note, that nobody wrote. This is the General, somewhat too bold, whose head was so hot, though his heart was so cold, who made himself single before it was meet, and his wife and his daughter turnd into the street, to appease the two Dukes, whose bitter rebukes made the two Marquisses shy of the horn, and caused the maiden all for Lorn, to become of a sudden so tatterd and torn, by means of Maam Bowing, to whom it was owing, that Mrs. Minifie Gunning was so very cunning, as to betray the groom, that carried the note, that nobody wrote.

Hastings, Selina, Countess of Huntingdon

E-Pr. 61:2 no. 1 ( July), pp. 6189. Letter from the late Countess of Huntingdon to Dr. Doddridge. [No date to it.]

Rev Sir, Since I wrote my last to you, I have received a letter from my beloved Dutchess of Somerset, who thus writes concerning you: I should be very glad to see any sermon of Dr. Doddridges, and should look upon a letter from him as an honour [] S. Huntingdon.

Copyright

Inchbald, Elizabeth

61:1 no. 3 (March), p. 255. 43. A Simple Story. By Mrs. Inchbald. In Four Volumes. 12mo. Among our ancestors it appears to have been thought a piece a gallantry to admire every thing that was the literary production of a lady. The Sapphos and the Corinnas of a hundred years ago were flattered and panegyrised for no mortal reason but because they wore a petticoat. At present, the case is altered; the fair sex has asserted its rank, and challenged that natural equality of intellect which nothing but the influence of human institutions could have concealed for a moment. One of the good effects of this revolution is, that Criticism becomes once more the office of Reason, and Gallantry surrenders the sceptre to Justice and Truth. Speaking with the frankness which these authorities dictate, we are ready to confess that we were not pleased with the dramatical productions of Mrs. I. There are in them some ingenuity of structure, and some merits of an inferior sort; but we search in vain for the glowing impressions of character, and the fervent enthusiasm of passion. What we wanted in the plays of this lady we have found in the Simple Story. She has struck out on a path entirely her own. She has

238

Romantic Women Writers Reviewed: Volume 7

Copyright

T. 61:1 no. 1 ( January), p. 86. Theatrical Register. T. 61:1 no. 3 (March), p. 287. Theatrical Register.

disdained to follow the steps of her predecessors, and to construct a new novel, as is too commonly done, out of the scraps and fragments of earlier inventors. Her principal character, the Roman Catholic lord, is perfectly new; and she has conducted him, through a series of surprizing and well-contrasted adventures, with an uniformity of character and truth of description that have rarely been surpassed. The novel, in reality, consists of two distinct histories; and the talisman by which they are united in this unity of character in its hero. We do not recollect an instance of an invention so happily calculated for the purpose of uniting events in their own nature unconnected and opposite. Every writer of a novel, in his moments of diffidence, will be inclined to tremble lest his production should be lost and forgotten amidst the immense lumber of trash that is hourly published under this description. This, however, is a difficulty, and not a discouragement; it should waken exertion, not incline to despondence. When conquered, the triumph is so much the more illustrious; and there are few records more honourable in the archives of literature than those of the labours of Richardson. Turgot, the virtuous and penetrating statesman of France, has asserted, that the science of morals is more impartially and effectually taught by romances than by any other species of composition. We predict that Mrs. Inchbald, especially if she can be prevailed upon to persist in the path she has so honourably begun, will rank amongst the first classes of those who, through this enchanting vehicle, have communicated instruction and improvement to mankind. In the midst of admiration we forgot censure; but we cannot stand excused to ourselves in omitting to notice, in spite of the beauties of this charming production, the painful sentiment excited by the catastrophe. It is so huddled and imperfect, that the feeling left upon the mind of the reader, when he closes the volumes, is that of imbecility; the strength of stamina in the novel is for a moment forgotten; and it is not till after a pause that he can call back his mind to recollect the eminent excellences by which this defect is so gloriously atoned.

Jan. 7. Covent-Garden. The Child of Nature [Performed with Rose and Colin and The Picture of Paris.]

March 2. Covent-Garden. The Midnight Hour [Performed with The Woodman.]

Gentlemans Magazine

239

T. 61:1 no. 5 (May), p. 495. Theatrical Register. May 11. Drury-Lane. The Hue and Cry [Performed with Love for Love.] May 31. Covent-Garden. The Midnight Hour [Performed with The Comedy of Errors and Soldiers Festival.] T. 61:1 no. 6 ( June), p. 591. Theatrical Register. June 13. Hay-Market. Ill Tell You What! [Performed with Agreeable Surprize.] June 17. Hay-Market. A Mogul Tale [Performed with Summer Amusement.] 61:2 no. 1 ( July), p. 687. Theatrical Register. July 9, 11, 12, 18, 20, 23, 27, 28, and 29. Hay-Market. Next Door Neighbours [Performed with a Ladys Half an Hour after Supper (9, 18, 23, and 29 July), The Author (9 July), Gretna Green (11 and 23 July), Seeing is Believing (11, 12, and 20 July), Inchbalds A Mogul Tale (12 July), A Quarter of an Hour before Dinner (14 and 27 July), The Citizen (14 July), The Son-in-Law (18 and 28 July), The Flitch of Bacon (20 and 27 July), and The Minor (29 July).] July 12. Hay-Market. A Mogul Tale [Performed with both Seeing is Believing and Inchbalds Next Door Neighbours.] T. 61:2 no. 2 (August), p. 783. Theatrical Review. Aug. 13 and 30. Hay-Market. Next Door Neighbours [Performed with both The Padlock and The Irishman in Spain (13 August) and both The Manager in Distress and Gretna Green (30 August).] T. 61.2 no. 5 (November), p. 1071. Theatrical Register. Nov. 19. Covent-Garden. The Midnight Hour [Performed with Artaxerxes.] T. 61:2 no. 6 (December), p. 1167. Theatrical Register. Dec. 13. Covent-Garden. Animal Magnetism [Performed with The Woodman.] Dec. 20. Covent-Garden. The Midnight Hour [Performed with The Duenna.]

Copyright

Notes to pages 22261

323

Gentlemans Magazine

1. 2. 3. 1790: This poems Latin epigram, adapted from the opening line of Politians Elegy on the Exile and Death of Ovid, is omitted here [CSB]. custos rotulorum: maintainer of county [CSB]. Jenny H: Judith Jennings in Gender, Religion, and Radicalism (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), pp. 878) identifies Jenny H as Jane Harry Thresher (175684). Born in Jamaica of an English father and a Jamaican slave mother, Thresher was identified in her obituary as an abolitionist [CSB]. stalking forth into the next world: Vice is every day [] stalking forth with more hardened effrontery, an assertion Johnson makes in his 1754 essay questioning the virtue of religious solitude (an important component of Quaker worship) [CSB]. Snake in the Grass: Charles Leslies (16501722) controversial 1696 anti-Quaker work The Snake in the Grass: or Satan transformed into an Angel of Light, which had run to three editions by 1698. See DNB [CSB]. A Switch for the Snake: Joseph Wyeths (16631731) 1699 Anguis Flagellatus: or a Switch for the Snake. Being an answer to the Third and Last edition of the Snake in the Grass. See DNB [CSB]. Heroes shadows: Aeneas confronted netherworld shades by Offering his brandishd weapon at their face, / Had not the Sibyl stopd his eager pace, / And told him what those empty phantoms were. See Popes translation of Virgil, Aeneid, VI.4048 [CSB]. A Constant Reader of the G. M.: James Kuist attributes this letter to Anna Seward. The Nichols File, p. 143 [CSB]. them: In the intervening paragraph which we have omitted as having nothing to do with Montague, the author of the letter inveighs against a Myriad of ignorant, stupid, or malicious Critics (p. 303). Monster: Between 1788 and 1790, Rhynwick Williams attacked several London women with a knife, leading to a panic among city-dwellers. The attacks were broadly reported in the periodical press, which deemed him the Monster; and his capture and trial captured imaginations throughout the country [SE]. Slander Hate: Alexander Popes Satires and Epistles of Homer, Imitated (book 2, satire 1, lines 814). See Alexander Popes Poetical Works, to which is Prefixed the Life of the Author of Alexander Pope, ed. Samuel Johnson (Philadelphia, PA: J. J. Woodward, 1836) [CSB]. In regard to there mentioned: see Letter to Lord Harvey, Works of Alexander Pope, vol. 8, p. 196 [CSB]. Mother Needham: Convicted on 29 April 1731 of pandering, Elizabeth Needham died after standing two days in the pillory and was memorialized in Hogarths 1731 The Harlots Progress. See DNB; and W. Hogarth and T. Cook, Anecdotes of the Celebrated William Hogarth (London, 1813), pp. 2636 [CSB]. tracd with a Sun-beam: Anna Sewards 1782 Poem to the Memory of Lady Millar. Tracd by a sun-beam, the broad letters blaze [SE]. Curl: Edmund Curll (16751747), a controversial London bookseller famous for his long-running and vituperative battles with Pope. See DNB [CSB]. Court Poems: Town Eclogues: Ironically, the 1716 volume Court Poems I. The Basset-Table. An Eclogue. II. The Drawing-Room. III. The Toilet (hereafter Montagus Court Poems) was in fact published in London as the Productions of a Lady of Quality. A 1716 Dublin publication by the same title identifies Pope as its author (hereafter Popes Court Poems).

4.

5.

6.

7.

8. 9.

10.

Copyright

11.

12. 13.

14. 15. 16.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- WORKSHEET (Interstate 60)Document5 pagesWORKSHEET (Interstate 60)Bényi OlgaNo ratings yet

- Expanded Orgasm Report 1 Patricia TaylorDocument12 pagesExpanded Orgasm Report 1 Patricia Taylorpatricia_taylor_1No ratings yet

- Index To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Document8 pagesIndex To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index To The Mysterious Science of The Sea, 1775-1943Document2 pagesIndex To The Mysterious Science of The Sea, 1775-1943Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945 PDFDocument3 pagesIntroduction To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945 PDFPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Victorian Medicine and Popular CultureDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Victorian Medicine and Popular CulturePickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Index To Victorian Medicine and Popular CultureDocument4 pagesIndex To Victorian Medicine and Popular CulturePickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Mysterious Science of The Sea, 1775-1943Document12 pagesIntroduction To The Mysterious Science of The Sea, 1775-1943Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Document9 pagesIntroduction To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945 PDFDocument3 pagesIntroduction To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945 PDFPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index To Standardization in MeasurementDocument6 pagesIndex To Standardization in MeasurementPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Adolphe Quetelet, Social Physics and The Average Men of Science, 1796-1874Document18 pagesIntroduction To Adolphe Quetelet, Social Physics and The Average Men of Science, 1796-1874Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945Document6 pagesIndex To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Sample Pages From The Miscellaneous Writings of Tobias SmollettDocument13 pagesSample Pages From The Miscellaneous Writings of Tobias SmollettPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Standardization in MeasurementDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Standardization in MeasurementPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Stress in Post-War Britain, 1945-85Document15 pagesIntroduction To Stress in Post-War Britain, 1945-85Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index To Victorian Literature and The Physics of The ImponderableDocument6 pagesIndex To Victorian Literature and The Physics of The ImponderablePickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index From Adolphe Quetelet, Social Physics and The Average Men of Science, 1796-1874Document5 pagesIndex From Adolphe Quetelet, Social Physics and The Average Men of Science, 1796-1874Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To MalvinaDocument12 pagesIntroduction To MalvinaPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Gothic Novel and The StageDocument22 pagesIntroduction To The Gothic Novel and The StagePickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- The Selected Works of Margaret Oliphant, Part VDocument18 pagesThe Selected Works of Margaret Oliphant, Part VPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index To Stress in Post-War Britain, 1945-85Document7 pagesIndex To Stress in Post-War Britain, 1945-85Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index To The Gothic Novel and The StageDocument4 pagesIndex To The Gothic Novel and The StagePickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Merchants and Trading in The Sixteenth CenturyDocument17 pagesIntroduction To Merchants and Trading in The Sixteenth CenturyPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Victorian Literature and The Physics of The ImponderableDocument17 pagesIntroduction To Victorian Literature and The Physics of The ImponderablePickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Index To Merchants and Trading in The Sixteenth CenturyDocument8 pagesIndex To Merchants and Trading in The Sixteenth CenturyPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830-1910Document18 pagesIntroduction To Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830-1910Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Indulgences After LutherDocument15 pagesIntroduction To Indulgences After LutherPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Early Modern Child in Art and HistoryDocument20 pagesIntroduction To The Early Modern Child in Art and HistoryPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index From Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830-1910Document5 pagesIndex From Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830-1910Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index From Indulgences After LutherDocument3 pagesIndex From Indulgences After LutherPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- ItDocument3 pagesIt?????No ratings yet

- ĐỀ 2Document6 pagesĐỀ 2Anh Mai NgọcNo ratings yet

- Intuisi 101: Vol 1 No, 2 Jurnal IlmiahDocument8 pagesIntuisi 101: Vol 1 No, 2 Jurnal IlmiahrukhailaunNo ratings yet

- Danh Động Từ Và Bài Tập: Choose the best answer for each of the following sentencesDocument3 pagesDanh Động Từ Và Bài Tập: Choose the best answer for each of the following sentencesBonbon NguyễnNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL-PROCEDURE - Q&aDocument28 pagesCRIMINAL-PROCEDURE - Q&aJeremias CusayNo ratings yet

- Emergency Response PlanDocument2 pagesEmergency Response PlanNikhil Chakravarthy VatsavayiNo ratings yet

- TE2091 MEETING and MINUTES & FORMAL LETTERDocument11 pagesTE2091 MEETING and MINUTES & FORMAL LETTERNUR KHAIRUNNISA AKMAR BT NORDIN (JTM-ADTECSHAHALAM)No ratings yet

- FM17-37 Air Cavalry Squadron 1969Document163 pagesFM17-37 Air Cavalry Squadron 1969dieudecafeNo ratings yet

- DeedDocument11 pagesDeedsunilkumar1988No ratings yet

- Sport GK PDFDocument127 pagesSport GK PDFRaja Aamir JavedNo ratings yet

- COLREG 1972 원문Document29 pagesCOLREG 1972 원문jinjin6719No ratings yet

- Paris Convention For The Protection of International PropertyDocument24 pagesParis Convention For The Protection of International PropertyNishita BhullarNo ratings yet

- United States v. George Uzzell, United States of America v. Vernon Uzzell, 780 F.2d 1143, 4th Cir. (1986)Document5 pagesUnited States v. George Uzzell, United States of America v. Vernon Uzzell, 780 F.2d 1143, 4th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Yale University Press History 2011 CatalogDocument36 pagesYale University Press History 2011 CatalogYale University Press100% (1)

- Contract 2Document9 pagesContract 2ANADI SONINo ratings yet

- 02-27-12 EditionDocument27 pages02-27-12 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- m1934 Subject ListDocument279 pagesm1934 Subject ListPierre Abramovici100% (1)

- GR 14078 - Rubi v. PB MindoroDocument2 pagesGR 14078 - Rubi v. PB MindoroChelsea CatiponNo ratings yet

- Cohen Monster CultureDocument23 pagesCohen Monster CultureLudmila SeráficaNo ratings yet

- Employee 1Document16 pagesEmployee 1Shivam RaiNo ratings yet

- Principle of Natural Justice - Chapter 9Document34 pagesPrinciple of Natural Justice - Chapter 9Sujana Koirala60% (5)

- Mint 10.04.2024?Document18 pagesMint 10.04.2024?yashh1708No ratings yet

- Cory Aquinos SpeechDocument19 pagesCory Aquinos SpeechLuke Demate Borja100% (4)

- Internal Security WorkbookDocument56 pagesInternal Security WorkbookSam PitraudaNo ratings yet

- Refugee Protection Act and Its Regulations. The Officer Will Ask To See This Letter, Your PassportDocument2 pagesRefugee Protection Act and Its Regulations. The Officer Will Ask To See This Letter, Your PassportDon Roseller DumayaNo ratings yet

- Xxx17index FileDocument2 pagesXxx17index FileMarcelo Bernardino CardosoNo ratings yet

- RETORIKA 1st Reporting (PPT) The Pros and Cons of Aquino and MarcosDocument14 pagesRETORIKA 1st Reporting (PPT) The Pros and Cons of Aquino and MarcosAlezandra Eveth HerreraNo ratings yet

- Elvis Wayne Jones v. The Texas Beaumont U.S. District Courts, 4th Cir. (2016)Document2 pagesElvis Wayne Jones v. The Texas Beaumont U.S. District Courts, 4th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet