Professional Documents

Culture Documents

p32 Central Theme

Uploaded by

lisahunCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

p32 Central Theme

Uploaded by

lisahunCopyright:

Available Formats

To be successful, any maintenance organisation worthy of the name will function via a number of necessary and inter-related managerial

and control systems. In his new book, Maintenance Systems and Documentation, Tony Kelly identifies those systems (performance control, work control, documentation, budgeting, costing etc.) that are key, showing how each can be mapped and modelled and its function and operating principles explained. As with his other books, the analysis is illustrated throughout by case studies drawn from his own wealth of experience, and readers can test their understanding of the lessons to be derived by addressing various review questions.

Some thoughts on

The central importance of budgeting to the formulation of maintenance strategy, is stressed and it is explained, by reference to real case examples, that the maintenance budget should be an expression of the forecasted short term (i.e. annual) and long term workloads in terms of the cost of internal labour, contract labour and the materials needed to deal with them. It is also emphasised that in plants requiring major shutdowns there is also the need for a specific turnaround budget. Budgeting procedures appropriate for large process plants are compared with those for individual manufacturing units and, finally, it is explained that, all too often, maintenance budgeting is rarely as rational as described, senior management seeing maintenance only as a cost and ignoring the linkage between maintenance expenditure and production output.

Maintenance Budgeting

Tony Kelly Consultant, Wilmslow, Cheshire (Recently Visiting Professor at the Universities of Central Queensland, Stellenbosch and Stavanger)

Annual income 20, annual expenditure 19.95 result happiness: annual income 20, annual expenditure 20.05 result misery

(Mr Micawber, in David Copperfield by Charles Dickens)

Key words: budgeting zero-based budgeting standard costs profit centre capital budget company revenue budget cost centre

t company level the function of control is to monitor outputs, compare these with what was expected, identify any deviation and then re-direct the companys effort as necessary. Budgetary control is one of the key elements of this, the preparation of a company budget being an integral part of the company planning process. Management are required to plan for production volumes to meet forecasted sales demand. This in turn requires a sales, production and maintenance budget. The budget can be regarded as the end point of the companys planning process in as much as it is a statement of the companys objectives and plans in revenue and/or cost terms It is a baseline document against which actual financial performance is measured. In control terms, budgets are based on standard costs which provide the expected (or planned) yearly expenditure profile. This is compared to the actual expenditures (cost control) and the variances over or under budget noted. Management then has information on which to base corrective action. Usually, the word budget is taken to refer to a particular financial year. However, the annual budget is often the first year of a rolling long term budget. For example, if a company has a strategic five-year plan it will normally align with a five-year rolling financial budget.

32 | July/Aug 2007 | ME

CENTRAL THEME

MAINTENANCE OBJECTIVE

(start here)

Business Production objective Saftey requirements

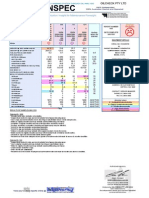

Typical examples of maintenance workloads are shown in Figures 2(a) and (b) and a detailed categorisation of the maintenance workload in Table 1. Essentially, maintenance budgeting is the expression of this forecasted workload in terms of the cost of internal labour, contract labour and materials needed to deal with it. It will be appreciated from Figure 2(a) that maintenance budgeting involves both the ongoing workload and also the major workload (overhauls, equipment replacement and modifications). It is important that the maintenance budget is set up to reflect the nature of the maintenance strategy and workload. There is a need for a longer term strategic maintenance budget that covers the Work Categories 7 and 8 as shown in Table 1. Much of this major work involves capital expenditure that can subsequently be depreciated by corporate management in the revenue budgets. In the shorter term there is a requirement for an annual maintenance expenditure budget that covers Work Categories 1 to 6 of Table 1. These costs feed into the company revenue budget that operates over the financial year. Continued on page 34

MAINTENANCE CONTROL

LIFEPLANS

Longevity requirements Production requirements (operating pattern, output etc.) Budget forecast

PREVENTIVE SCHEDULE WORKLOAD

MAINTENANCE ORGANISATION Strategic thought process In uencing factors Control

Figure 1 Relationship between maintenance strategy and budgeting

MAINTENANCE BUDGETING

The need for a maintenance budget arises from the overall budgeting need of corporate management and involves estimation of the cost of the resources (labour, spares etc.) that will be needed in the next financial year to meet the expected maintenance workload. This is best explained via Figure 1. The maintenance life plans and schedule have been laid down to achieve the maintenance objective (which incorporates the production needs, e.g. operating pattern and availability) and in turn generates the maintenance workload.

Main Category

FIRST LINE

Sub-category

Correctiveemergency

Category number

(1)

Comments

Occurs with random incidence and little warning and the job times also vary greatly. In some industries (e.g. power generation) failures can generate major work, these are usually infrequent but cause large work peaks. Occurs in the same way as emergency corrective work but does not require urgent attention; it can be deferred until time and maintenance resources are available. Work repeated at short intervals, normally involving inspections and/or lubrication and/or minor replacements. Same characteristics as (2) but of longer duration and requiring major planning and scheduling. Involves minor off-line work carried out at short or medium length intervals. Scheduled with time tolerances for slotting and work smoothing purposes. Similar to deferred work but is carried out away from the plant (second line maintenance) and usually by a separate tradeforce. Involves overhauls of plant or plant sections or major units. Can be planned and scheduled some time ahead. The modification workload (often capital work) tends to rise to a peak at the end of the company financial year.

Maintenance Resources

First line Second line Third line

Correctivedeferred (minor)

Shutdown work

(2)

100 1st and 2nd line work 1 2 3

Preventiveroutines SECOND LINE Correctivedeferred (major) Preventiveservices

(3)

Figure 2 (a) Power station workload

YEARS

(4)

(5)

~250 ~ Maintenance Resource Weekend planned maintenance Weekday 1st line maintenance via shift cover Emergency maintenance Summ er shutdown maintena nce

First line Second line Third line

Correctivereconditioning and fabrication THIRD LINE Preventive-major work (overhauls etc) Modifications

(6)

(7)

10 on each shift

4 WE EKS

50

(8)

Figure 2 (b) Food processing plant workload

Table 1 Categorisation of maintenance workload by organisational characteristics

ME | July/Aug 2007 | 33

CENTRAL THEME

In plants requiring major shutdowns there is also the need for specific turnaround budgets which are an integral part of the turnaround planning procedure. The maintenance budgeting procedure is facilitated by identifying plant cost centres and, where necessary, continuing the identification down to unit level. A cost centre in an alumina refinery, for example, might be coded as follows: Cost Centre Digestion Area 6 Unit Bauxite Mills C 02 Unique Unit Number

THE BUDGETING PROCEDURE

The budgeting procedure depends on the type of administration in operation. In a functional organisation of the kind used in large integrated plants e.g. in an alumina refinery (see Figure 3), the strategic maintenance budget is set up by the Chief Engineer with contributions from the Maintenance Manager, Services Manager and the Plant Manager. A typical major work schedule for an alumina refinery is shown in Figure 4 (The refinery never comes off line it is designed to allow the major plant sections to be maintained while it is still operating at full or reduced load. The major workload tends to be scheduled in such a way as to avoid the major work peaks). Such a schedule extends for at least ten years and is used to identify the large, low-frequency, high-cost, maintenance jobs and the capital replacement work. This information is used to set up the strategic maintenance budget. The major work schedule shown in Figure 4 also includes some of the higher frequency maintenance work which, in conjunction with the maintenance routines and services, is also covered in the annual maintenance expenditure budget. The annual budget is built up from the budget for each plant and workshop. For example, the mechanical maintenance for the Digestion Area can be estimated, from the expected area workload, by the Digestion Mechanical Superintendent, translated into resources needed, and added to similar estimates from other plant areas and disciplines (see Figure 5). Budgeting for the preventive work (Categories 3 and 5) is relatively straightforward. Corrective work (Categories 1, 2, 4 and 6) presents a more difficult problem. Nevertheless, if a history record is available it is often possible to estimate, with acceptable accuracy, the level of corrective work to be expected for a given level of preventive effort. Without such experience little confidence can be placed in the estimate and this must be made clear in the budget statement. The workshops and services areas needed to be tackled differently, because their workload originates from each of the plant areas. This approach is sometimes called Zero-based Budgeting (ZBB) because the maintenance budget is built up from scratch each year in the light of the maintenance schedule for that year. The above budgeting procedures need modification for an administrative structure based on manufacturing units (see Figure 6). Each manufacturing unit becomes a profit centre, and a combined production/ maintenance budget is required at Operations Manager level. The centralised maintenance functions become cost centres and budgets for the service they provide to the manufacturing units. These centralised maintenance functions are concerned with efficiency of resource usage rather than plant Continued on page 36

Over the designated financial period the actual maintenance cost (of labour, spares, tools) are collected against these cost centres to enable cost monitoring and control (viz. cost control) to be undertaken. Cost control complements budgeting.

Most large process plants use some form of strategic maintenance budgeting which matches their long term preventive schedule (e.g. see the power station workload, Figure 2 (a) ). Some food processing plants, however, do not use strategic maintenance budgets. This is because their maintenance strategies are based on simple routines and inspections (a wait and see policy) they schedule neither long term major maintenance nor, in some cases, the replacement of capital equipment (which I find surprising).

Refinery Manager

Commercial Manager

Technical Manager Staff

Chief Engineer Staff

Production Manager

Plant Maintenance Manager

Maintenance Services Manager

Manager Purchasing and Stores

other area production supts

Digestion Digestion other area Support Electrical Production Mech mech suptsEngineers Instrument Maintenance Supt. Supt. Supt. Digestion Digestion Mech Production Supvs Supvs Digestion Digestion Mech Production trades Operators Digestion other E/I area E/I Supvs Supvs

Plant Services Maintenance Supt.

Workshop Supt.

E/I Supv. Supv. Supv. Workshop Supv. services trades

Supv. Supv. Supv.

E/I trades

mechanical workshop trades.

OTHER PLANT AREAS

DIGESTION AREA

Figure 3 Alumina refinery functional administration

34 | July/Aug 2007 | ME

ID 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36

Name Boilerhouse Boilers Boiler - 4 Boiler - 7 Boiler - 2 Turbo-Alternators Turbo-Alternators - 1 Digestion Unit Shutdowns Unit 1 Unit 1 B/O Tank Conversion Unit 2 Unit 2 B/O Tank Conversion Unit 3 Unit 3 B/O Tank Conversion Digesters Unit 1 Digester 1 Digester 1 Digester 2 Digester 3 Unit 2 Digester 4 Digester 5 Digester 5 Digeaster 6 Digester 6 Unit 3 Digester 7

2000 Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun

2001 Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb

1/5

26/5 12/7

27/7 1/9

5/3

20/7 23/3 23/4

1/4 1/6

31/5

1/8

1/10

30/9

30/11

1/4

31/5

31/7 1/12

1/1

2/3

30/1

15/1

This article was published in Maintenance & Asset Management journal, Volume 21 No 4. It first appeared in Volume 3 - Maintenance Systems and Documentation - of the 3 part Plant Maintenance Management Set written by Tony Kelly and published by Butterworth Heinemann. The other titles in the series are Strategic Maintenance Planning and Managing Maintenance Resources - see previous page (p.35) for further details, including cost and method of ordering.

Figure 4 Extract from major work schedule

Refinery budget (Refinery Manager)

availability they act like internal contractors and the costing system is designed to reflect this situation. In practice, maintenance budgeting is rarely as rational as described. Senior management see maintenance only as a cost. The linkage between maintenance expenditure and production output indicated in Figure 1 is often ignored. Maintenance budgeting then becomes an exercise based on last years costs plus an allowance for inflation (at best low frequency major work may be included). This is a poor form of budgeting, it is an attempt to forecast what is likely to be spent in the absence of any management intention to deviate from what has gone before.

Stores budget

Production budget Maintenance budget (Plant Maintenance Manager)

Other budget inputs

Mechanical maintenance budget (Plant Maintenance Manager) From other areas Clarification area mechanical budget (Clarification Mech. Supt )

E/I budget (Services Manager)

Workshop and services budget (Services Manager)

Digestion area mechanical budget (Digestion Mech. Supt )

Electrical maintenance budget (E/I Supt )

Instrument maintenance budget (E/I supt )

Plant services budget (Services Supt )

Mechanical workshop budget (Workshop Supt )

Refinery Manager Shift Managers (Mon to Fri cover)

Figure 5 Build-up of refinery expenditure budget

CommercialTechnical Manager Manager

Plant Engineer

Digestion Operations Manager

Clarification Preciptation Clacination Utilities Operations Operations Operations Operations Manager Manager Manager Manager Similar in principle to digestion

Maintenance Manager

Staff

Staff

Staff

Digest Process Support Eng. Product Shift Supv(s) Shift teams

Plant Plant Plant MaintenanceDigestion Digestion Officer Officer Officer Resource Planner Support A B C Officer Engineer

Maintenance Plant Service Workshop Contracts Supt. Supt. Supt. Support Engineer Staff Staff

Mech Supv. A

Mech Mech Supv. Supv. B C

E/I Supv

T/A planning E and I CBM supervision engineersengineer(s) Centralised shift team MEI first line maintenance

Second line mech. resouce. area specialisation with flexibility

DIGESTION MANUFACTURING UNIT

Teams Teams

Figure 6 Administrative structure based on manufacturing units

36 | July/Aug 2007 | ME

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Beyond Mine Dispatch - Optimizing The Mining Value Chain - Wenco Mining SystemsDocument5 pagesBeyond Mine Dispatch - Optimizing The Mining Value Chain - Wenco Mining Systemslisahun100% (1)

- Customer Cat ET OverviewDocument36 pagesCustomer Cat ET Overviewlisahun100% (5)

- 992G HYD TroubleshootingDocument9 pages992G HYD TroubleshootinglisahunNo ratings yet

- 773E ToolingListDocument12 pages773E ToolingListlisahunNo ratings yet

- AMMJ Knowledge Centre Past Issue SummariesDocument4 pagesAMMJ Knowledge Centre Past Issue SummarieslisahunNo ratings yet

- Fuel Filter RestrictionDocument2 pagesFuel Filter RestrictionlisahunNo ratings yet

- Gps Positioning and SurveyingDocument62 pagesGps Positioning and SurveyinglisahunNo ratings yet

- Manpower Calculator Introduction V1.5Document18 pagesManpower Calculator Introduction V1.5lisahunNo ratings yet

- Coda Training31Document5 pagesCoda Training31lisahunNo ratings yet

- Geosat 8 UpdDocument19 pagesGeosat 8 UpdlisahunNo ratings yet

- Fuel Dilution of Engine OilDocument2 pagesFuel Dilution of Engine Oillisahun100% (3)

- DT 101 HydraulicDocument2 pagesDT 101 HydrauliclisahunNo ratings yet

- Dealer Stocking ListDocument6 pagesDealer Stocking ListlisahunNo ratings yet

- Lowongan Kerja Husky-CNOOC Madura Limited Februari 2015Document4 pagesLowongan Kerja Husky-CNOOC Madura Limited Februari 2015lisahunNo ratings yet

- DT-94 EventDocument6 pagesDT-94 EventlisahunNo ratings yet

- Lowongan Kerja MRT Jakarta Februari 2015Document5 pagesLowongan Kerja MRT Jakarta Februari 2015lisahunNo ratings yet

- DT 102 EventDocument17 pagesDT 102 EventlisahunNo ratings yet

- McBride Music Company - Woodwind and Brass Instrument RepairDocument2 pagesMcBride Music Company - Woodwind and Brass Instrument Repairlisahun0% (1)

- Welding PrecautionDocument2 pagesWelding Precautionlisahun100% (1)

- Maintenance ORSDocument4 pagesMaintenance ORSlisahun100% (1)

- ORS Hardware and SchematicsDocument11 pagesORS Hardware and Schematicslisahun100% (1)

- Marketing BulletinDocument7 pagesMarketing BulletinlisahunNo ratings yet

- Powered Stairway SystemDocument4 pagesPowered Stairway Systemlisahun0% (1)

- Automatic Retarder Control (ARC)Document5 pagesAutomatic Retarder Control (ARC)lisahun100% (1)

- Certified Marine AnalystDocument1 pageCertified Marine AnalystlisahunNo ratings yet

- Powered Stairway SystemDocument4 pagesPowered Stairway Systemlisahun0% (1)

- Engine ReportDocument2 pagesEngine ReportlisahunNo ratings yet

- PECJ0003-05 July2014Document448 pagesPECJ0003-05 July2014lisahunNo ratings yet

- EM SystemDocument11 pagesEM SystemlisahunNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- International Financial Management: Jeff Madura 7 EditionDocument27 pagesInternational Financial Management: Jeff Madura 7 EditionHamid KhurshidNo ratings yet

- Baumol Model NDocument5 pagesBaumol Model NGaurav SharmaNo ratings yet

- Government AccountingDocument6 pagesGovernment AccountingroliNo ratings yet

- Bond Valuation Synopsis IGNOUDocument3 pagesBond Valuation Synopsis IGNOUSenthil kumarNo ratings yet

- Ai Trading ApplicationDocument28 pagesAi Trading ApplicationAbhijeet PradhanNo ratings yet

- 2014 3M Annual ReportDocument132 pages2014 3M Annual ReportRitvik SadanaNo ratings yet

- Austral Coke ScamDocument3 pagesAustral Coke ScamMohit GiriNo ratings yet

- Understanding Macro Economics PerformanceDocument118 pagesUnderstanding Macro Economics PerformanceViral SavlaNo ratings yet

- Business of Banking (Volumul II) PDFDocument328 pagesBusiness of Banking (Volumul II) PDFminusdas540No ratings yet

- Currency Future & Option For StudentsDocument8 pagesCurrency Future & Option For StudentsAmit SinhaNo ratings yet

- Apple Matrik SpaceDocument25 pagesApple Matrik SpaceChandra SusiloNo ratings yet

- Tough LekkaluDocument42 pagesTough Lekkaludeviprasad03No ratings yet

- LIC Housing FinanceDocument25 pagesLIC Housing Financepatelnayan22No ratings yet

- Guide To MSCI Global Islamic IndicesDocument29 pagesGuide To MSCI Global Islamic Indicesbrendan lanzaNo ratings yet

- CA Ghana Professional Exams: Audit and Assurance CommentsDocument24 pagesCA Ghana Professional Exams: Audit and Assurance CommentsmohedNo ratings yet

- Two Asset Portfolio Risk and Return AnalysisDocument10 pagesTwo Asset Portfolio Risk and Return AnalysisSagar KansalNo ratings yet

- FULL Publication 2017 - Web PDFDocument57 pagesFULL Publication 2017 - Web PDFIsidor GrigorasNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of SFP ElementsDocument33 pagesFundamentals of SFP ElementsAbyel Nebur100% (2)

- Mokoagouw, Angie Lisy (Advance Problem Chapter 1)Document14 pagesMokoagouw, Angie Lisy (Advance Problem Chapter 1)AngieNo ratings yet

- Leasing Companies in BDDocument21 pagesLeasing Companies in BDMd Tareq50% (2)

- Low Latency White PaperDocument3 pagesLow Latency White PapersmallakeNo ratings yet

- Three Basic Candlestick Formations To Improve Your TimingDocument4 pagesThree Basic Candlestick Formations To Improve Your TimingelisaNo ratings yet

- Group 10-Mexican Peso CrisisDocument10 pagesGroup 10-Mexican Peso CrisisTianqi LiNo ratings yet

- The Figures in The Margin On The Right Side Indicate Full MarksDocument8 pagesThe Figures in The Margin On The Right Side Indicate Full MarksManas Kumar SahooNo ratings yet

- Assigment BBM Finacial AccountingDocument6 pagesAssigment BBM Finacial Accountingtripathi_indramani5185No ratings yet

- Solution 4 27Document12 pagesSolution 4 27hind alteneijiNo ratings yet

- Laporan Arus KasDocument22 pagesLaporan Arus KasdianpujipsNo ratings yet

- Tankeh vs. DBP (Digest)Document1 pageTankeh vs. DBP (Digest)Ana Altiso100% (2)

- Role of UTI in mobilizing savings and assisting corporate sectorDocument2 pagesRole of UTI in mobilizing savings and assisting corporate sectorsnehachandan9167% (3)

- Documentary Evidence of AuthorityDocument6 pagesDocumentary Evidence of AuthorityMichael Kovach100% (6)