Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Governance

Uploaded by

aryatartaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Governance

Uploaded by

aryatartaCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [andi luhur prianto] On: 22 July 2012, At: 00:58 Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Critical Policy Studies

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcps20

Governance without governance: how nature policy was democratized in the Netherlands

Esther Turnhout & Marille Van der Zouwen

a a b

Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands

b

KWR Watercycle Research Institute, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands Version of record first published: 16 Dec 2010

To cite this article: Esther Turnhout & Marille Van der Zouwen (2010): Governance without governance: how nature policy was democratized in the Netherlands, Critical Policy Studies, 4:4, 344-361 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2010.525899

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Critical Policy Studies Vol. 4, No. 4, December 2010, 344361

Governance without governance1 : how nature policy was democratized in the Netherlands

Esther Turnhouta* and Marille Van der Zouwenb

Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands; b KWR Watercycle Research Institute, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands Trends in governance, including a changing role for the state and increasing civil society participation, are often seen as promising ways to achieve democratic legitimacy. The prominent presence of these claims and intentions in the new Dutch nature policy plan, Nature for People, People for Nature, stimulated us to look more closely into how this plan came about. Our analysis shows that the process started with the organization of several informal participatory processes, which involved not only traditional but also new actors. However, it ended in a fairly traditional way, with limited participation, which involved mostly traditional actors, and which was strictly orchestrated by central government. Based on these ndings, we argue that although the plan itself was clearly intended to achieve participatory governance, the participatory characteristics of the process can be questioned. For this reason, the case may be seen as one of governance without governance. The article ends by discussing the implications of these ndings for democratic legitimacy. Keywords: civil society; participation; governance; nature conservation policy; legitimacy

a

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

Governance in Dutch nature policy and the democratization of nature In 2000 the Dutch parliament adopted a new nature policy plan with the eye-catching title Nature for People, People for Nature. The following quotes taken from the rst page of the plan show the titles intriguing meaning (LNV 2000, p. 1):

The Government has opted for a broader nature policy to do more justice to the signicance of nature for society; The Government wishes to simplify the policy system and introduce programs which integrate objectives; The term [nature] as we use it embraces nature from the wildlife on peoples doorstep to the Wadden Sea. This is how most people perceive nature; Nature for people means that nature should meet the demands of society and should be within easy reach, accessible and usable. People for nature means nature should be protected, managed, cultivated and developed by people. [Government] will take responsibility where necessary but [will] also, more than in the past, remind others of their responsibility.

*Corresponding author. Email: esther.turnhout@wur.nl

ISSN 1946-0171 print/ISSN 1946-018X online 2010 Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham DOI: 10.1080/19460171.2010.525899 http://www.informaworld.com

Critical Policy Studies

345

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

As the citations above illustrate, the rhetoric of the policy plan is clear enough. First of all, the plan offers a broad and integrated conception of nature. It presents nature as part of a countryside which harbors different interests and functions (e.g. conservation, recreation, agriculture). Second, the plan emphasizes peoples wishes, perceptions and preferences as a legitimate basis for nature policy. Third, the plan indicates that people, rather than government, should take responsibility for nature conservation. These three elements are connected: it is expected that if nature meets peoples wishes, the people will in turn protect it, thereby enhancing the legitimacy and efciency of nature policy. When compared to its predecessor, this plan constitutes a dramatic change in nature policy. The 1990 Nature Policy Plan (LNV 1990) was characterized by a dominance of natural science expertise (Turnhout 2003, 2009). Conservation decisions and priorities were informed by ecological insights about ecosystems and about the ecological effects of human use and management. It was full of ecological science terms such as gene-reservoir, self-regulation, completeness, intactness, ecosystems and communities. Furthermore, it had quite a different take on the relationship between nature and people as the following citation illustrates:

Minimization of human inuence is seen as conditional for maximization of natural values (LNV 1990).

In comparison, it can be argued that the new plan aims for a democratization of nature. Nature is no longer the exclusive domain of ecological experts and the importance of peoples participation in nature, in dening nature, and in the governance of nature, has been recognized. In this new nature policy plan, the Dutch government, in particular the Ministry of LNV (Dutch acronym for Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality), presents a way of steering that emphasizes state withdrawal and public involvement and participation. It resonates with current ideas about governance. In the scientic literature from various scientic disciplines, governance is predominantly conceptualized in terms of processes and procedures (Turnhout 2010). An important issue in the governance literature, for example, is how to organize the relationships between interdependent actors from state, market and civil society in an effective, accountable and legitimate way (Van Kersbergen and Van Waarden 2004). Often, the underlying assumption is that these governance processes, almost by default, result in good and legitimate policies. In this article we start with the content of the policy plan and ask how it was developed, what the role of participants was and how formal participation practices were related to informal participation practices. The Dutch context provides interesting opportunities for analyzing processes of participatory governance. The Netherlands political culture is known for its long tradition of corporatism and accommodation (Lijphart 1968, Van Waarden 1992). A lot of policy development and implementation has taken place in sectoral iron triangles: elites of actors from government, interest groups and parliament who have frequently interacted to make agreements and resolve differences. This was common in nature policy too. Traditional societal interest groups such as forest and other landowners, site managers and nature conservation organizations had excellent access to decision-makers and civil servants and in that way had much inuence on policy development. In some other European countries too, close contacts traditionally exist between governmental parties and interest organizations as regards nature conservation issues (see for instance Van der Zouwen 2006 for the UK and Spain). A case study on the Netherlands will give insight into what participatory

346

E. Turnhout and M. Van der Zouwen

governance looks like in a corporatist tradition which is characterized by participation, albeit in rather closed and elitist structures.

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

Civil society governance and participation Among academics and policy practitioners there is much debate about crises occurring in state-led policy processes, gaps between politics and citizenry and a variety of trends manifesting themselves in response to these crises. The literature on the term governance generally assumes that policy processes are characterized by a shift from traditional, hierarchical government settings to governance, emphasizing the complexity and plurality of policy processes. Multi-level governance, which points to the increasing interconnectedness of the various political arenas due to processes such as devolution, Europeanization and globalization (e.g. Hooghe and Marks 2001), is one element contributing to this complexity. Also in terms of actors, increasing plurality is recognized. Changing ideas about the role of the state (e.g. Kooiman 2000, Pierre and Peters 2000) have created space for the participation of citizens and non governmental organizations (e.g. Arts 1998). In these complex processes, as Hajer and Wagenaar (2003, p. 9) state:

There are no pre-given rules that determine who is responsible, who has authority over whom, what sort of accountability is to be expected.

Interactions between actors are increasingly informal, ad hoc and temporary and take place outside traditional institutions and outside the exclusive centers of political power (Hajer 2003, Van der Zouwen 2006). Also, ideas about what kinds of knowledge and expertise are relevant and legitimate have changed, emphasizing the importance of lay knowledge and multi- and trans-disciplinary perspectives (e.g. Funtowicz and Ravetz 1993, Gibbons et al. 1994, Jasanoff 1997). One of the prominent features of current governance theories is the increased role of non-state actors. The involvement of civil society organizations and the public are considered crucial to increase the democratic quality and legitimacy of policy processes as well as their effectiveness and efciency (Innes and Booher 1999, Bulkeley and Mol 2003). Participation is generally seen as a dening characteristic of good governance and is promoted by various international organizations such as the European Commission and the World Bank. Participatory or civil society governance is increasingly recognized as an important concept to set alongside those of hierarchical and market governance. At the same time, however, participatory governance is complex and contested. Many different methods, tools and forms of participation exist and there is little agreement on what exactly constitutes a good participatory process. Arnsteins (1969) ladder of participation serves the purpose of distinguishing between low levels of participation, which amount to little more than tokenism and manipulation, and higher levels of participation, which empower the participants. In a similar vein, Goodwin (1998) distinguishes between hired hands and local voices. Other authors refrain from such judgments and argue that different participatory tools serve different ends. Van Asselt and Rijkens-Klomp (2002) distinguish between two objectives achieving consensus and mapping diversity and argue that both require different participatory tools. In a similar vein, Pellizioni (2001a), Fiorino (1990) and Rowe and Frewer (2000) each offer different typologies of participatory tools and their effectiveness in meeting conditions and objectives such as the extent to which they offer possibilities for reection and discussion, their potential to achieve

Critical Policy Studies

347

consensual decisions, the likelihood that the outcomes will be accepted and their potential to achieve equal relations among participants. What these authors have in common is a focus on the formal intentions or objectives of participation as regards procedures for organizing participation and the choice of methods or tools. Consequently, they pay little attention to what happens when these participatory intentions and tools are put into practice (Turnhout et al. 2010). Critical analyses of participation have demonstrated that participatory practices often deviate from their formal intentions and objectives. Participation has been shown to lead to exclusion, the suppression of differences and the strengthening and reproduction of existing power inequalities (Mohan and Stokke 2000, Cooke and Kothari 2001, Pellizioni 2001b, ONeill 2001). Furthermore, the relationship between participatory levels or methods and outcome is not straightforward. For example, Lawrence (2006) has shown how consultation, which is considered low level participation, did result in genuine involvement and empowerment of the participants. Recognizing the importance of participatory practices implies looking not only at what happens in formal participatory practices, but also at what happens behind the scenes in informal practices. These informal practices are not organized invited spaces, but popular or public ones that emerge organically based on common concerns (Cornwall 2002). In contrast to formal practice, informal practices are not driven by pre-given rules and have the potential for rule alteration and innovation (Cornwall 2002, Van Tatenhove et al. 2006). Although these distinctions between formal and informal and between invited and popular are useful for focusing attention on the oft neglected informal forms of participation, they are also overly dichotomous (Kesby 2007). Instead of treating them as distinct and disconnected, it is important to recognize the many interactions between them and analyze how formal and informal participatory practices mutually inuence and shape each other (Nandigama 2009). Accordingly, participatory processes can be conceived as performative practices in the sense that the roles that participants play and the interests they represent do not preexist but are shaped in the participatory process: they are performed (Turnhout et al. 2010). This makes clear that participation cannot be evaluated in terms of objectives that were set or tools that were applied. Understanding participation requires in-depth analysis of the different, formal and informal, participatory practices and the relationships between them. With this in mind we refer to Van Tatenhove et al. (2006), who describe two different kinds of strategies that are used to link formal and informal practices: cooperative strategies and conictual strategies. Cooperative strategies are used by actors who set out to strengthen the relationship between formal and informal practices, for example by means of mutual learning and reection. Conictual strategies are used by actors who set out to weaken this relation, for example by excluding other actors. In this article we will use the categories cooperative and conictual to typify the strategies we encounter in the case study. However, strategies do not completely determine what happens in practice. It remains to be seen, for example, if cooperative strategies also result in a cooperative relationship. For the purpose of this article, it is important to look not only at the strategies and the intentions of the actors that mobilize them, but also at the relationships between informal and formal practices that result from them. Subsequently, understanding participatory processes as performative practices forms the basis for discussing democratic legitimacy. Democratic legitimacy comes in (at least) two different modalities: input legitimacy, which is concerned with issues such as whether the right tool was selected, the right procedures followed and the right people invited; and output legitimacy, which is concerned with the quality of the outcomes of the participatory

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

348

E. Turnhout and M. Van der Zouwen

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

process (Joerges and Neyer 2003). While achieving input legitimacy is often associated with participatory forms of governance, output legitimacy can also be achieved through the playing of a strong role by central government. In line with our perspective on participation as performative practice, we consider input and output legitimacy as attributes that are achieved in practice. Based on these theoretical considerations, this article analyzes how the different, formal and informal, participatory practices interacted in the development of this plan and discusses the implications for democratic legitimacy as it has been achieved (or not) in practice. Our reconstruction of the development process is based on extensive research into the archives of the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (LNV). The archives of the specic dossier contained approximately six boxes lled with les. All of these were searched for relevant documents such as letters and correspondence by the ministry with participants, minutes of meetings, internal memos and draft documents. In particular, we looked for drafts of the new nature policy document, discussions that were going on within the project team and the steering group and with the secretary of state, reports on the different participatory meetings that were organized with societal actors, letters that were written in response to the different drafts of the plan, and communication with other ministerial departments. The selected documents were carefully analyzed according to date, in order to reconstruct the order of events and the roles of the different actors in the policy process. In addition, we conducted ve interviews with key players in the development of the policy plan, which were recorded and transcribed (see appendix). The ve interviewees comprise the two project leaders, the secretary of state, a project team member and a member of a societal group. The respondents were selected to address specic issues that resulted from the document analysis regarding the order of events in the reconstructed development process, the roles of the different actors involved, the content of discussions and the nature of interactions.

Towards a new nature policy plan This section presents the background of, and the starting points for, the new nature policy plans development. These starting points were to a large extent inuenced by strong criticisms of the old plan which focused on the plans ecological dominance and top down character (WRR 1998). The old plan also suffered from considerable implementation problems, which were believed to be due to a lack of citizen involvement and of political attention to peoples wishes concerning nature (LNV 1994). Subsequently, the Dutch Advisory Council for the Rural Area, which consists of scientists as well as representatives of societal organizations, advised that:

Policy must go further in the sense of including more goals to strengthen the links with society and the broad spectrum of wishes and expectations people have regarding nature. (RLG 1998)

In 1999, the government evaluated the old nature policy plan. In line with earlier criticisms, the report emphasized the importance of broadening nature policy to include societal aspects (LNV and IPO 1999). The evaluation also concluded that nature policy was too complex and fragmented and should strive for integral approaches. This related to the wish to simplify the policy system by integrating the so-called green policy documents: the landscape policy plan (LNV 1992), the nature policy plan (LNV 1990), the forest policy plan (LNV 1993) and the Vision on Urban Landscapes (LNV 1996).

Critical Policy Studies

349

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

Although they largely came from central government and corporatist organizations such as the Raad voor het Landelijk Gebied (RLG), these evaluations did give out a strong signal about the lack of societal support for nature policy and they served as important inputs for the new nature policy plan. Based on these inputs, the project team for the development of the new nature policy plan had three main starting points: (1) to integrate nature, forest and landscape policy into the new plan; (2) to broaden the concept of nature: not only ecological criteria but also the societal values and functions of nature would be included in nature policy; and (3) to organize the development process in an open and participatory way. A participatory approach was considered essential for an integrated and broad perspective on nature in the new policy plan. These starting points are strongly related to the nal contents of the plan. They emphasize the importance of participation, an integrated approach and a broad conception of nature. The project team consisted of 12 members: eight LNV civil servants from different departments (nature, agriculture, rural areas, regional branches), one civil servant from the Ministry of Spatial Planning and the Environment (VROM), one from the Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management (V&W) and two representatives from regional authorities. The composition of the team reects the ambition to involve actors from different administrative levels and sectors. The three starting points were shared among the members of the project team. For example, the Secretary of State, politically responsible for the new plan, was a strong supporter of integration. Referring to her experience in local government she said:

I had enough of all these policy documents from central government and now [as a Secretary of State] I had the position to do something about it. (Interview 2)

The Secretary of State was also very much in favor of broadening the concept of nature:

We had some discussions on what is nature. And I remember that at a certain point I said it is from a plant in a pot to the Wadden Sea. It is also that people, that was really important to me, can enjoy nature. That you not only have some beautiful places hidden away. (Interview 2)

A member of the project team made the link between broadening the concept of nature and societal support:

At the moment that you say that is not real nature . . . then you cut off a lot of support [for nature policy]. . . . If scientists determine this is nature and this is not, then you may question whether or not you link up with the interests of the public. (Interview 1)

Opening policy up to peoples wishes also related to ideals on how the process should be organized. A member of the project team stated:

If you want to involve more actors . . . you will only be able to achieve that if you allow them to provide input in the entire development process. That was our intention. (Interview 1)

This section has made clear that already in this early stage, the terms of the new plan had been largely set. The following sections will show how the development process continued and how it shifted from a rst stage in which informal participatory practices and cooperative strategies dominated, to a second stage of increasing (conictual) formalization and nally to a third stage in which cooperative strategies and informal practices emerged again while formal practices remained important.

350

E. Turnhout and M. Van der Zouwen

The rst stage: doing things differently Taking into account the starting points of a broad and integrated perspective on nature, the Secretary of State and the project leader realized that it was important to do things differently. First of all, they organized informal settings (three in total) in which a large variety of non-governmental organizations could freely exchange their thoughts about nature policy (Invitation letter Secretary of State 18 January 1999). Interestingly, many of the participants were not part of the group of actors usually consulted on nature policy, e.g. a regional branch of the National Agriculture Union (LTO), a cooperative bank (Rabobank), the Federation of Private Landowners (FPG) and the General Building Association (AVBB). According to the project leader, it was the explicit intention to invite new actors and facilitate new coalitions:

We categorized the [different actors]: the site managers, other ministries, agriculture [and also included] sectors that were traditionally further removed from nature. . . . We wanted to see if combinations were possible. . . . That was a very important change. (Interview 3)

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

The newcomers highly appreciated the openness and the ministrys willingness to let them engage in such an early stage of the process. Also, they acknowledged the importance of an integrated perspective on nature. At the same time however, some especially the traditional nature conservation actors feared that all this attention given to participation, peoples wishes and integration might come at the expense of traditional nature management and conservation issues (Report of the meeting 26 January 1999). A second change with respect to business as usual participation involved the composition of the project team. Normally, such a project team would consist of civil servants from the Ministry of LNV only, but in this case also regional authorities and other ministries were also involved in the project team. Third, the broad and integrated perspective on nature which had to be central to the new nature policy plan made the likely input of internal ministerial nature conservation experts less self evident. They were even explicitly excluded at the early stage. Other ministries and regional authorities were also involved in a steering group. This formal group did not play a very important role. It met for the rst time on 1 April 1999, which was signicantly later than the rst informal session with new societal actors, and only ve days before the publication of the rst draft of the new plan. In this rst draft, the three starting points of integration, broadening the concept of nature and participation were prominently present. The following quote illustrates that integration is assumed to contribute to the overall effectiveness of nature policy:

This policy document replaces three earlier policy documents, the nature policy plan, the landscape policy document and the forest policy plan. Integration of these documents in one new document for nature and landscape will strengthen consistency and efcacy in these policy elds. (p. 6)

Also, participation is emphasized:

This policy document . . . invites the different actors to take responsibility for nature and landscape . . . It is important to make good arrangements with partners. (p. 7)

An entire section was dedicated to broadening the concept of nature. The following serves as a nice illustration:

Ideas about the concept of nature change. . . . This means that nature policy can not assume one central view of nature. Not only large wild areas like the Wadden sea . . . are nature, but

Critical Policy Studies

351

also cultivated parks . . . Recognizing and acknowledging the diversity in views of nature is an important challenge for the coming years and important for support for nature policy. More and more, peoples wishes become an input for policy processes. (p. 15)

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

The ministry distributed the draft to more than 100 organizations, several of which were already involved in the development process. Many actors engaged in this formal participatory practice by sending their comments to the ministry. The comments were largely positive: the actors expressed their appreciation of being involved at this early stage and in general endorsed the plans main lines, strategies and goals (LNV 1999). Next to these positive comments, actors generally asked for further clarications and elaboration of the main lines of argument, strategies and goals, for example concerning the degradation of rural areas and the role of agriculture, and the vagueness of terms such as peoples nature wishes. Despite this broad support, resistance to the plan arose within the LNV. The Secretary of State recalls:

It was difcult in the beginning. The mindset within the Nature department [of the LNV] was very much dominated by ecologists and biologists. And this was understandable, because they had eventually achieved something with the Ecological Main Structure and then someone says hey, but thats not all. (Interview 2)

Several LNV experts who were excluded from the development process, because they did not participate in the project team, feared that certain topics in nature policy were no longer explicitly dealt with and that they were loosing ground as regards their elds of specialization. As two project team members recall:

There were also people who felt that they were losing ground. They started to search the draft to count the number of times that their particular word of interest was mentioned. (Interview 3) [civil servants involved in] species protection for example were angry because [their topic] wasnt covered well enough in the plan. Literally, it was about the number of pages in the document. (Interview 1)

Based on these concerns, these internal experts were formally invited by the project leader to deliver specic input on their elds of specialization. The results of this are reected in the second draft of the new nature policy plan, which was published on 29 July 1999. The second draft, though considerably bigger than the rst one, shows no major changes in the main lines of the plan. Each of the three starting points is, again, prominently present. The draft presents the importance of broadening the concept of nature in a way that is very similar to the rst draft:

It has become clear that nature, forest and landscape policies should be linked to the wishes of society. (p. 1)

The need for policy integration in this draft is not solely based on arguments related to effectiveness, but is also clearly linked to the broadening of the concept of nature:

The need for integration comes from the observation that the distinction between nature, forest and landscape is less self-evident than has been assumed in scientic and policy circles. Also the concept biodiversity . . . has to link up with what is perceived in society. (p. 2)

352

E. Turnhout and M. Van der Zouwen

Participation is in this draft explicitly related to ideas of joint responsibility and interactive decision-making:

Increasingly society has proven to be capable in different ways of taking their own responsibility for solving problems . . . With this policy document . . . we want to contribute to stimulating this active society in order to achieve and maintain the desired quality of nature, forest and landscape. (pp. 34) Nature may be a . . . right . . . but not without obligations. . . . People for nature means . . . that decision-making about nature requires broad involvement. To stimulate and use this involvement we want to promote interactive . . . decision-making. (p. 22)

This section makes clear that broad informal participatory settings, in which new actors would be invited to participate, would lead to support for the main lines of the plan. However, some actors were excluded and the struggles this caused eventually resulted in the publication of a sizeable second draft.

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

The second stage: formalization and closing down space for participation The reactions to the second draft were not positive. The Secretary of State qualied it as overly detailed and lacking vision:

I received a 180 page draft nature policy plan to take on holiday . . . And then I said, I am throwing this in the bin. I am not even going to read this. Well, I did sort of look through it, but it was just all more of the same. (Interview 2)

She commissioned a new draft of around 20 pages:

I want it to be short . . . with only the essentials. You dont have to repeat what we already know. Make it a real policy plan. (Interview 2)

She also appointed an additional project leader alongside the one already in place. The two project leaders were asked to deliver a new draft with a more general character and consisting of fewer pages. The two project leaders took up the challenge and started writing in relative isolation. Around three weeks later (15 September 1999) they delivered the rst version of what came to be known as the main lines document. They also reduced the size of the project team to ve members, all of whom were from the Nature Department within the ministry:

We . . . halved the project team. That was not easy, people who had put their energy into it, all of a sudden, they were put aside. . . . I dont believe that project teams should be big. (Interview 3)

This meant that the new actors, from the regional governments and other ministries disappeared from the project team. The idea was that a smaller and internal project team would ensure more commitment within LNV and a high-quality policy document. Rather than delivering the input themselves, the project team would make sure that the relevant input would be provided by others in the organization:

If a certain topic concerned the department of green space and recreation, I wanted them to deliver the input. . . . Under the direction of the project group, but the content had to come from the organization itself. (Interview 3)

Critical Policy Studies

353

Furthermore, the steering group was replaced by an inter-ministerial advisory group. This group had to formally coordinate the input of the different policy sectors at the national level. The biggest change was the absence of regional governmental representatives in the advisory group. According to the Secretary of State this was necessary because the steering group had not functioned well:

It didnt work and everything was discussed over and over again. It just wasnt effective. (Interview 2)

In November 1999 the inter-ministerial advisory group discussed a draft of the main lines document. During this meeting, the relative lack of inter-ministerial coordination (due to the malfunctioning of the steering group and its late involvement in the process) proved problematic. All participants were unanimous in their negative reactions. One of their criticisms concerned the absence of a spatial and nancial framework. As a representative from the Ministry of Finance stated:

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

To approve the plan is to approve a blank check. (Internal memo Roemers 30 November 1999)

Furthermore, they criticized the plans ignorance towards other important policy plans under development (e.g. the fth spatial policy plan). Finally, ministerial representatives were dissatised about how their involvement was arranged. As a representative from the Ministry of Economic Affairs put it:

We now have a version which has the approval of the Minister and Secretary of State for LNV . This has taken months and now they are in a big hurry to coordinate things with us. We barely have time to make up our minds and to discuss it properly. (Letter Huiskamp 26 November 1999)

Despite these criticisms, a draft of the main lines document was submitted to be discussed in two formal practices. First of all, in an extra meeting of the Rijksplanologische Commissie (RPC)2 on 9 December 1999. Although the RPC expressed its general support, it was critical of the lack of further elaboration of spatial and nancial claims. The RPC recommended submitting it to the Raad voor Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieu (RROM)3 as an intended policy. This draft, to which the comments of the RPC had been added, was published on 10 December 1999 and was discussed in the RROM meeting of 14 December 1999. As it only focused on the main lines, it was much shorter than the second draft. In this draft, the integration of forest, nature and landscape policy and the broadening of the concept of nature are legitimized by an appeal to peoples wishes about nature:

Government chooses to broaden nature policy in order to do better justice to the meaning of nature policy for society. (p. 1) It is nature from the front door to the Wadden Sea. This links up with the perceptions of people. (p. 1)

State withdrawal is emphasized to create room for participation and enable other actors to be actively involved:

A central government is required that . . . leaves space for its partners to maneuver [and] increases the possibilities for citizens and organizations to take responsibility for nature. (pp. 2526)

354

E. Turnhout and M. Van der Zouwen

The RROM did not approve the draft. Apparently, this was a disappointment for the project team:

We had already selected a cover with a winter landscape for the main lines document. But we didnt get permission from the RROM to go to parliament with it. (Interview 3)

The Secretary of State, however, explains that sending this draft to the RROM was a strategic, conictual, move to create a sense of commitment and urgency:

We knew it wouldnt get approval. (Interview 2) What we did is that we put this main lines document up for discussion in the [RPC and RROM]. With that we created inter-ministerial and political commitment about the main lines, and we made an agreement that it would be further elaborated. (Interview 2)

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

This phase saw increasing formalization and exclusion of the new actors who were involved in the rst phase. In these rather closed processes, the draft had been reduced again to main lines only.

The third stage: opening up space for traditional actors The project team realized that the previous phase had been rather closed but intended that this should be only temporary:

First we had to decide for ourselves what our priorities would be and from then on the process [of communication and interaction with societal actors, other ministries and the provinces] started again. (Interview 3)

However, this interaction with societal actors had a very different character. Instead of broad informal sessions, rather closed, specic and selective meetings took place:

[Participation] was very specic. We . . . actively initiated interaction, formal and informal. Perhaps the informal communication was the most important. . . . Telephone calls, conversations with a bag of peanuts on the table. (Interview 3)

In these formal and informal settings, cooperative strategies were used to create support. They included meetings with, for example, the Inter Provincial Organization (IPO) and the Industrial Board for Forestry and Silviculture and presentations for organizations such as the Society for the Preservation of Nature Monuments, the State Forestry Service (SBB) and the national employers organization (VNO-NCW). The issues addressed mainly concerned the strategic main lines as presented in the December 1999 draft. However, not everybody was content with discussing main lines only. Nature conservation organizations in particular wanted more information on how the policy would work out in practice. They were concerned that an integrated and broadened perspective on nature would lead to insufcient attention to species and habitat conservation and that the plan would fail to organize the strict spatial protection of nature (internal LNV report 19 February 2000). Also the reactions from several organizations, including the IPO, the State Forestry Service, the Recreation Platform (Platform Ruimte voor Recreatie) and the Royal Dutch Automobile Association (ANWB) to the December 1999 draft showed that these actors, in general, supported the main goals and strategies, but were critical as to how these would be elaborated on in a policy program.

Critical Policy Studies

355

By now, formal participatory settings had started to dominate the process. The publication of the nal draft of the new nature policy plan had a tight deadline. This was related to the planning of the fth memorandum on spatial planning, which the Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment was preparing at that time. It was important for the Ministry of LNV to publish the nature policy plan rst, because in that way it could have an impact on the spatial policy plan:

[If] Nature for people [the nature policy plan] [is] rst, . . . that is a good basis for having an inuence [on the spatial planning plan]. (Interview 2) Those things that were relevant spatially . . . would have to be included in [the fth memorandum on spatial planning]. (Interview 3)

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

To meet this deadline interactions with the other ministries regarding the elaboration of the nancial and spatial implications of the new nature policy plan had to be smooth and effective. According to the project leader, the conictual strategy of sending the draft to the RROM in December 1999 to create commitment now really paid off:

The Ministries of Economic Affairs, of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment, and of Transport, Public Works and Water Management cooperated very constructively. This was possible because there was a main lines document that they could agree with. (Interview 3)

The Secretary of State too emphasizes this, even though she does remember that the rejection by the RROM was far from pleasant:

It wasnt nice . . . but with hindsight, the most important benet was that afterwards there was a strong commitment, shared by the other ministries, to cooperate. (Interview 2)

Informal settings were required as well to resolve some remaining issues. To deal with the concerns of the Ministry of Finance that the plan would be a blank check, the Secretary of State for LNV and the Minister of Finance together agreed on some phrases that were to be included in the plan:

I believe that in the nal document you can nd some formal passages: they occur in three or four places, I think. It was the Ministry of Finance that required that, a passage to indicate [the extent to which our ambitions were actually covered nancially]. (Interview 3)

Another meeting between the Secretary of State and the Minister and Secretary of State for Transport, Public Works and Water Management was held to sort out some issues which pertained to the question of who would be responsible for, and pay for, plans to realize new nature areas along rivers. The remainder of the development process was relatively unproblematic. On 23 May 2000, a draft of the new plan was discussed in the RPC. In general, the participants were positive and it was felt that the remaining nancial and spatial issues could easily be resolved at the highest civil servant level (Internal LNV report 30 May 2000). Finally, on 20 June 2000, the RPC concluded that the new plan was ready for nal political decisionmaking and could be discussed in the RROM meeting of 4 July 2000. On 14 July 2000, the nal policy plan was sent to parliament. Participatory practices and strategies What we have seen in the case study is a dynamic process with different strategies and practices. The rst phase was guided by a general desire to do things differently. The

356

E. Turnhout and M. Van der Zouwen

informal meetings with a wide range of new societal actors constitute informal participatory practices characterized by cooperative strategies which were aimed at organizing support. Judging from the largely positive responses to the rst draft, these participatory practices really paid off and strengthened the formal process. Also, the project team could be seen as such an informal participatory practice, as it involved new actors from other ministries and from the regional governments. New actors from the regional governments were also involved in the steering group. However, alongside cooperative strategies, doing things differently required conictual strategies as well. Internal experts on nature conservation, who would traditionally have been involved, were explicitly excluded from the project team. Also, the late involvement of the steering group (whose rst meeting took place only right before the publication of the rst draft) reects such a conictual strategy. Both led to struggles and resistance later on in the process. The project team accommodated the criticisms of the internal LNV experts by allowing them to provide input. However, this led to a sizeable second draft which was not received positively. The second phase was characterized by the abandonment of informal participatory practices and increasing formalization. Conictual strategies were involved in removing the new actors from the project team, which now had a rather traditional composition of only internal LNV civil servants. They were also removed from the steering group, which subsequently changed into an inter-ministerial advisory group. Societal actors were also hardly involved in this phase. During the second phase, the two project leaders from the Ministry of LNV again reduced the second draft to main lines only. This draft was discussed in the inter-ministerial advisory group. The groups negative reaction to the content of the plan as well as to its limited involvement clearly demonstrates the conictual and formal character of the discussion. The decision of the Secretary of State to send the draft to the RROM, despite these criticisms, is very interesting in this respect. Although it certainly has a confrontational and conictual ring to it, the intention was that discussing the plan in the RROM even if it resulted in rejection would strengthen the formal process, smooth the nalization of the plan and create support among the other ministries. In that way, it can be seen as a cooperative strategy as well. In the third phase we nd mainly formal participatory practices and cooperative strategies. The ministry arranged meetings with (mainly traditional) societal actors to discuss specic topics in order to smooth differences and strengthen support. Also, bilateral meetings were organized with other ministries to resolve some remaining nancial and spatial issues. Overall, the development process started with informal participatory practices that involved a wide range not only of traditional actors but also of new societal actors. However, the informal participation settings created in the rst phase were quickly abandoned in favor of the increased involvement of internal LNV civil servants in the second phase and strictly orchestrated formal participatory practices with mainly traditional actors in the third phase. Throughout the process, the central government remained rmly in charge and the participatory practices involved ended up strongly resembling the old corporatist practices so characteristic of the Dutch context. Was Dutch nature policy democratized? One of the intriguing ndings of the analysis is that, throughout the development process, the content of the policy plan was relatively stable. The plans main themes broadening the

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

Critical Policy Studies

357

concept of nature, including peoples wishes, integrating different policies, and changing the role of government were present right from the start as lessons learnt from the evaluation and as starting points for the project team. Regardless of the dynamics in the process in terms of actor involvement, the actors participation changed little in the content of the plan. Based on this, it could be argued that all the participation that was organized, the importance that was attached to inviting new actors, the emphasis on doing things differently, served only to legitimize decisions already taken and priorities already set. Indeed, one of the main criticisms of participation is that it tends to assimilate participants into projects with pre-established objectives and strengthens these projects with a new participatory legitimacy (Kabeer 1996, Partt 2004, Turnhout et al. 2010). Also, there are clear signs that throughout the process, the central government remained rmly in charge. It was the Ministry of LNV who organized the participatory processes and set the terms regarding who was invited and what was discussed. The role of the government grew stronger in the second and third stage of the process, in which it rst closed down possibilities for informal participatory practices and later opened up space for participation again, but in a traditional and rather elitist and corporatist way. Thus, there are ample reasons to question the input legitimacy of the policy. Although actors were involved in the process, for example by attending meetings and submitting comments, the stability of the content implies that their inuence is, to say the least, difcult to detect. It appears that the use of cooperative strategies to involve new actors resulted in practices of assimilation and incorporation rather than cooperation. However, a different reading of the case study is possible as well. Our ndings suggest that a large number of the actors involved in the process were positive about the new themes that the plan introduced. They were happy to be involved and they expressed their support for the main lines of the plan. The main criticisms that were received pertained to concerns about the details of how the main lines would be elaborated. This suggests that the Ministry of LNV has learned from its experiences with the previous nature policy plan.4 That they have effectively dealt with the lack of societal support for nature policy by recognizing the importance of linking up with peoples perceptions and wishes and including these in the new plan. The democratization of nature policy, as it is expressed in the new plan, did not result from the development process. Participation was designed to sell the new themes and ideas to a civil society that, apparently, was already willing to buy. The positive reactions to the main lines of the plan throughout the process attest to its output legitimacy. The two readings of the case study show that, while the input legitimacy was questionable, output legitimacy was achieved. The question of whether Dutch nature policy was democratized can now be answered with a qualied yes: democratic legitimacy has been achieved but in terms of content, not of process. This qualication is important because our analysis does not include the actual implementation of the plan. The extent to which nature policy has been democratized on the ground remains to be seen. It could be argued that democratic legitimacy was achieved not in spite of, but thanks to, a government dominated setting. In a more open setting the outcomes would have been more unpredictable. In this case, participation could have resulted in a new plan that did not include a broad concept of nature and failed to link up with peoples wishes. There were actors within civil society as well as within the department of LNV who advocated a more traditional approach and a narrow concept of nature, based on ecological science. In the Dutch context, with its corporatist tradition, it is not unlikely that these actors would

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

358

E. Turnhout and M. Van der Zouwen

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

have been successful in using the participatory spaces available to them to meet their ends. In this case, democratic legitimacy could arguably only have been achieved with a rm government hand. In much of the literature, civil society governance and participation are seen as promising ways to ensure democratic legitimacy. Governance processes that involve civil society and imply a changing (more limited) role of government are considered key factors in increasing the legitimacy of policies and decisions. Our ndings demonstrate how, without governance processes, governance ambitions were institutionalized in a new policy plan. In that sense, our case is one of governance without governance, or put another way governance by government. Based on this, we argue that the procedural view on democratic legitimacy, which is implicit in much of the contemporary literature, is an insufcient basis for understanding participation and civil society governance and for evaluating democratic legitimacy. In addition to procedures, it is important to consider the outputs of these processes, that is, the content or substance of governance. Second, it is important not to dismiss central government as an important actor in achieving democratic legitimacy, and to recognize its potential to play a constructive role in organizing output legitimacy. More importantly though, we feel that to understand governance and participation, it is crucial to investigate them as practices, and to focus on the links and relationships between them: for example, the relationship between input and output, or between process and substance, which, as our case has shown, may or may not be straightforward; or the links between formal and informal participatory practices, which may strengthen as well as undermine each other. It is in the practices and the interactions between them that participation occurs, that democratic legitimacy is negotiated, and that civil society governance is shaped.

Acknowledgements

The study this article reports on was conducted as part of and funded under the EU 6th framework project GoFOR on new modes of governance for sustainable forestry in Europe.

Notes on contributors

Esther Turnhout is Associate Professor at the Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group, Wageningen University, the Netherlands. Her research and teaching concern the relationship between science and non-science in the elds of environmental governance, nature conservation, forestry, biodiversity politics and natural resource management. Current research projects focus on: the labeling of species as invasive in the biodiversity debate; the role of volunteers in biodiversity recording; and democratic legitimacy in the EU Water Framework Directive. She has published several international journal articles on topics such as the science policy interface, ecological indicators, classication and standardization, boundary objects, boundary work, volunteer recording and public participation. Marille Van der Zouwen is a senior scientist at the KWR Watercycle Research Institute, The Netherlands. Her PhD research focused on multilevel governance and the implementation of Natura 2000 in The Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom and resulted in 2006 in the publication of the book Nature policy between trends and traditions dynamics in nature policy arrangements in the Yorkshire Dales, Doana and the Veluwe (Eburon). Before starting her activities at KWR in 2009 she worked as an Assistant Professor at the Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group, Wageningen University, the Netherlands. Her research and teaching there concerned policy analysis and trends in multilevel and global governance. Her current activities at KWR focus on science system assessment and the functioning and governance of knowledge networks in the water sector.

Critical Policy Studies Notes

1. 2.

359

3. 4.

The title is paraphrasing the much used term in the governance literature governance (or governing) without government (Rhodes 1996, Peters and Pierre 1998). The RPC is the committee that is concerned with the inter-ministerial coordination of spatial planning issues. It mainly consists of top-level civil servants (often director-generals) from all ministries. They prepare agenda items that will then be taken to the sub-ministerial Council for Spatial Planning (RROM). The RROM is the sub-ministerial Council for Spatial Planning in which the decisions of the ministerial council are prepared. It consists of ministers and state secretaries, complemented with the chair of the RPC and several top-level civil servants. This reects a certain degree of input legitimacy to be sure. The starting points of the new plan were based on criticisms of the old plan, which stemmed from society. However, it was the central government who decided to take these into account and translated them into the main lines of the new plan.

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

References

Arnstein, S.R., 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American planning association, 35 (4), 216224. Arts, B., 1998. The political inuence of global NGOs. Case studies on the climate and biodiversity conventions. Utrecht: International Books. Bulkeley, H. and Mol, A.P.J., 2003. Participation and environmental governance: consensus, ambivalence and debate. Environmental values, 12 (2), 143154. Cooke, B. and Kothari, U., 2001. The case for participation as tyranny. In: B. Cooke and U. Kothari, eds. Participation, the new tyranny? London: Zed Books, 115. Cornwall, A., 2002. Making spaces, changing places: situating participation in development. Institute of Development Studies, IDS Working Paper 170. Fiorino, D.J., 1990. Citizen participation and environmental risk: a survey of institutional mechanisms. Science, technology, & human values, 15 (2), 226243. Funtowicz, S.O. and Ravetz, J.R., 1993. Science for the post normal age. Futures, September, 739755. Gibbons, M., et al., 1994. The new production of knowledge the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: SAGE. Goodwin, P., 1998. Hired hands or local voice: understandings and experience of local participation in conservation. Transactions of the institute of British geographers, 23 (4), 481499. Hajer, M.A., 2003. Policy without polity? Policy analysis and the institutional void. Policy sciences, 36 (2), 175195. Hajer, M.A. and Wagenaar H., eds., 2003. Deliberative policy analysis, understanding governance in the network society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hooghe, L. and Marks, G., 2001. Multi-level governance and European integration. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littleeld. Innes, J.E. and Booher, D.E., 1999. Consensus building and complex adaptive systems. Journal of the American planning association, 65 (4), 412423. Jasanoff, S., 1997. Civilization and madness: The great BSE scare of 1996. Public understanding of science, 6 (3), 221236. Joerges, C. and Neyer, J., 2003. Politics, risk management, World Trade Organisation governance and the limits of legalisation. Science and public policy, 30 (3), 219225. Kabeer, N., 1996. Reversed realities: gender hierarchies in development thought. New Delhi: Kali for Women. Kesby, M., 2007. Spatialising participatory approaches: the contribution of geography to a mature debate. Environment and planning A, 39 (12), 28132831. Kooiman, J., 2000. Societal governance: levels, modes, and orders of socialpolitical interaction. In: J. Pierre, ed. Debating governance: authenticity, steering, and democracy. Oxford University Press, 138166. Lawrence, A., 2006. No personal motive? Volunteers, biodiversity, and the false dichotomies of participation. Ethics, place and environment, 9 (3), 279298. Lijphart, A., 1968. The politics of accommodation, pluralism and democracy in the Netherlands. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

360

E. Turnhout and M. Van der Zouwen

LNV, 1990. Natuurbeleidsplan, regeringsbeslissing. Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij. Tweede Kamer, vergaderjaar 19891990, 21149, nrs. 23. LNV, 1992. Nota landschap, regeringsbeslissing. Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij. LNV, 1993. Bosbeleidsplan. Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij. LNV, 1994. Natuurbeleid in de peiling, een tussentijdse balans van het Natuurbeleidsplan. Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij. LNV, 1996. Visie stadslandschappen, discussienota. Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij. LNV, 1999. Verzameling reacties of eerste concept, met twee aanvullingen. Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij. LNV, 2000. Nature for people people for nature: nature, forest and landscape in the 21st century. Ministry of LNV: The Hague. LNV and IPO, 1999. Evaluatie van het natuur-, bos- en landschapsbeleid . Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij, Interprovinciaal Overleg. Mohan, G. and Stokke, K., 2000. Participatory development and empowerment: the dangers of localism. Third world quarterly, 21 (2), 247268. Nandigama, S., 2009. Transformations in the making: actor-networks, elite-control and gender dynamics in community forest management intervention in Adavipalli, Andhra Pradesh, India. Thesis (PhD), International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University (ISS), The Netherlands. ONeill, J., 2001. Representing people, representing nature, representing the world. Environment and planning C , 19 (4), 483500. Partt, T., 2004. The ambiguity of participation: a qualied defence of participatory development. Third world quarterly, 25 (3), 537556. Pellizzoni, L., 2001a. Democracy and the governance of uncertainty, the case of agricultural gene technologies. Journal of hazardous materials, 86 (1), 205222. Pellizzoni, L., 2001b. The myth of the best argument: power, deliberation and reason. British journal of sociology, 52 (1), 5986. Peters, B.G. and Pierre, J., 1998. Governance without government? Rethinking public administration. Journal of public administration theory and research, 8 (2), 223243. Pierre, J. and Peters, B.G., 2000. Governance, politics & the state. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Rhodes, R.A.W., 1996. The new governance: governing without government. Political studies, 44, 652667. RLG, 1998. Natuurbeleid dat verder gaat, advies over voorgang en vernieuwing van het natuurbeleid . Raad voor het Landelijk Gebied. Report number 98/8. Rowe, G. and Frewer, L.J., 2000. Public participation methods, a framework for evaluation. Science, technology, & human values, 25 (1), 329. Turnhout, E., 2003. Ecological indicators in Dutch nature conservation: science and policy intertwined in the classication and evaluation of nature. Amsterdam: Aksant. Turnhout, E., 2009. The effectiveness of boundary objects: the case of ecological indicators. Science and public policy, 36 (5), 403412. Turnhout, E., 2010. Heads in the clouds: knowledge democracy as a utopian dream. In: R.J. In t Veld, ed. Knowledge democracy, consequences for science, politics and media. Berlin: Springer, 2536. Turnhout, E., Van Bommel, S. and Aarts, N., 2010. How participation creates citizens: participatory governance as performative practice. Ecology and Society, 15 (4), 26. Available from: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art26/. Van Asselt, M.B.A. and Rijkens-Klomp, N., 2002. A look in the mirror: reection on participation in integrated assessment from a methodological perspective. Global environmental change, 12 (3), 107180. Van Kersbergen, K. and Van Waarden, F., 2004. Governance as a bridge between disciplines: cross-disciplinary inspiration regarding shifts in governance and problems of governability, accountability and legitimacy. European journal of political research, 43 (2), 143171. Van der Zouwen, M.W., 2006. Nature policy between trends and traditions dynamics in nature policy arrangements in the Yorkshire Dales, Doana and the Veluwe. Delft: Eburon. Van Tatenhove, J., Mak, J. and Liefferink, D., 2006. The inter-play between formal and informal practices. Perspectives on European politics and society, 7 (1), 824.

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

Critical Policy Studies

361

Van Waarden, F., 1992. The historical institutionalization of typical national patterns in policy networks between state and industry. A comparison of the USA and the Netherlands. European journal of political research, 21 (12), 131162. WRR, 1998. Ruimtelijke ontwikkelingspolitiek . Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid. Report number 53.

Appendix Respondents

Interview 1: Interview 2: Interview 3: Interview 4: Interview 5: Former member of the project team, Ministry of LNV. Former Secretary of state for Nature, Ministry of LNV. Second former project leader and member of the project team, Ministry of LNV. First former project leader and member of the project team, Ministry of LNV. Former secretary of the Dutch Industrial Board for Forestry and Silviculture.

Downloaded by [andi luhur prianto] at 00:58 22 July 2012

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The I Ching (Book of Changes) - A Critical Translation of The Ancient TextDocument464 pagesThe I Ching (Book of Changes) - A Critical Translation of The Ancient TextPhuc Ngoc88% (16)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Negotiation Skills: Training Manual Corporate Training MaterialsDocument10 pagesNegotiation Skills: Training Manual Corporate Training MaterialsMaria Sally Diaz-Padilla100% (1)

- Violence Against Women in IndiaDocument5 pagesViolence Against Women in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Types of Speech StylesDocument4 pagesTypes of Speech StylesAiresh Lumanao SalinasNo ratings yet

- Art History as Cultural History【】Document304 pagesArt History as Cultural History【】Min HuangNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - The Principle of Fashion - The NewDocument15 pagesChapter 2 - The Principle of Fashion - The NewyhiNo ratings yet

- Rizal and Philippine Nationalism: Learning OutcomesDocument8 pagesRizal and Philippine Nationalism: Learning OutcomesMa. Millen Madraga0% (1)

- Infographic Rubric: Exceeds Expectations Meets Expectations Developing Unacceptable Use of Class TimeDocument1 pageInfographic Rubric: Exceeds Expectations Meets Expectations Developing Unacceptable Use of Class TimeBayliegh Hickle100% (1)

- Alex Klaasse Resume 24 June 2015Document1 pageAlex Klaasse Resume 24 June 2015api-317449980No ratings yet

- Eka's Korean BreakthroughDocument1 pageEka's Korean BreakthroughEka KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Thus at Least Presuppose, and Should Perhaps Make Explicit, A Normative AccountDocument5 pagesThus at Least Presuppose, and Should Perhaps Make Explicit, A Normative AccountPio Guieb AguilarNo ratings yet

- Britain Quiz - OupDocument3 pagesBritain Quiz - OupÝ Nguyễn NhưNo ratings yet

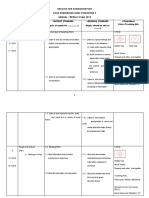

- English For Communication KSSM Pendidikan Khas Tingkatan 3 Annual / Weekly Plan 2019Document27 pagesEnglish For Communication KSSM Pendidikan Khas Tingkatan 3 Annual / Weekly Plan 2019LEE VI VLY MoeNo ratings yet

- 2 Ingles English Reinforcement Worksheet Unit OneDocument3 pages2 Ingles English Reinforcement Worksheet Unit OneEva Alarcon GonzalezNo ratings yet

- English Worksheet Third Term 2019-2020Document4 pagesEnglish Worksheet Third Term 2019-2020DANIELNo ratings yet

- Roaring 20s PPDocument11 pagesRoaring 20s PPapi-385685813No ratings yet

- DBQ Captains of Industry or Robber BaronsDocument5 pagesDBQ Captains of Industry or Robber Baronsapi-281321560No ratings yet

- HCI Lecture 1Document15 pagesHCI Lecture 1sumaira tufailNo ratings yet

- Definition of Research by Different Authors: Lyceum-Northwestern University Master of Arts (Maed) Dagupan City, PangasinanDocument2 pagesDefinition of Research by Different Authors: Lyceum-Northwestern University Master of Arts (Maed) Dagupan City, Pangasinanlydenia raquelNo ratings yet

- Man Is Inquisitive by NatureDocument2 pagesMan Is Inquisitive by Natureparagon2008No ratings yet

- Internaltional ManagementDocument28 pagesInternaltional ManagementramyathecuteNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 bm102Document6 pagesAssignment 1 bm102Star69 Stay schemin2No ratings yet

- Bahrain Media Roundup: Read MoreDocument4 pagesBahrain Media Roundup: Read MoreBahrainJDMNo ratings yet

- Auto AntonymsDocument4 pagesAuto AntonymsMarina ✫ Bačić KrižanecNo ratings yet

- CFLMDocument3 pagesCFLMRosemarie LigutanNo ratings yet

- Facilitation Form: Skill Development Council PeshawarDocument3 pagesFacilitation Form: Skill Development Council Peshawarmuhaamad sajjad100% (1)

- Tableau WhitePaper US47605621 FINAL-2Document21 pagesTableau WhitePaper US47605621 FINAL-2Ashutosh GaurNo ratings yet

- Writing Skills Practice: An Invitation - Exercises: PreparationDocument2 pagesWriting Skills Practice: An Invitation - Exercises: Preparationساجده لرب العالمينNo ratings yet

- Culture VietnamDocument16 pagesCulture VietnamCamila PinzonNo ratings yet

- Unit 4: Extra Practice: KeyDocument2 pagesUnit 4: Extra Practice: KeyBenjamíns Eduardo SegoviaNo ratings yet