Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sudha Ji's Informal Submission in TAC Case

Uploaded by

hnlu_subhroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sudha Ji's Informal Submission in TAC Case

Uploaded by

hnlu_subhroCopyright:

Available Formats

To, Honble The Chief justice, High Court of Chhattisgarh.

Subject: submission in good faith, to assist the court in WP (PIL) 23/2012, BK Manish Vs. State of Chhattisgarh & Another. Respected Sir, It is known that my name has cropped up twice in reference to the said case despite the fact that i have no formal link to it. It is also generally accepted that the case, being directly associated with operationalisation of Fifth Schedule, is of wide import as its outcome may affect millions of adivasis in Chhattisgarh, and outside. An Amicus Curie has been appointed to assist the court considering the complexities of the case. Indeed it can be said that in the course of justice the Bench does not just face complexities of purely legal nature but the complexities incidentally run far beyond the questions of law and venture into the field of history, psychology and socio-political justice. It is in this context that I have taken initiative to go through the submissions made so far and realized the imminent danger of miscarriage of justice primarily on account of the narrow reading of constitutional provisions and case laws. Also, I believe it would be a travesty of justice to adivasis, the most oppressed class of our country, if the lack of hard work in preparing submission leads to this great opportunity going in vain. Therefore Im compelled to make following informal submission in good faith to safeguard not just the justice but also the honour of my High Court: 1. Contention of the petitioner and the relevant provisions of Constitution as also of the impugned Rules have been adequately and repeatedly referred to in the submissions so I am focusing on facts in the background and their inter-relation. First, the general overview: 2. The petitioner has not merely challenged the constitutional validity of Chhattisgarh Tribal advisory Council Rules, 2006, rather the instant petition is titled, unconstitutional functioning of Tribes Advisory Council and challenge to the impugned rules is just a part of it; 5 out of 7 grounds in the petition do not have any reference to impugned rules at all. In fact a similar writ petition challenging unconstitutional functioning of TAC, currently in process in Odisha has made the minutes of a TAC meeting the basis to establish violation of sub-para 4(2) of Fifth schedule. 3. The question of Locus Standi was taken leniently by this court in this case and now it stands resolved after the rejoinder of the petitioner and the submission of the Amicus Curie. 4. The question of improper pleading has been raised both in terms of maintainability and the merit. The point on maintainability arose due to unconventional drafting by one side and poor reading on the other side. A careful reading shows that the petitioner has indeed provided adequate causes and grounds in support of his contention although not in a standard manner. By highlighting the fact that the impugned rules have been formulated by the state government and not the office of governor along with

the rulings of Supreme Court in Samata Case and PESA case, quoted in the petition, the petitioner did build a case of constitutional violation in terms of legislative incompetence. If it can be accepted that provisions of Fifth Schedule are akin to constitutional rights of scheduled tribes, then rulings of Supreme Court in Fertiliser Corporation Kamgaar case and Balco employees case further strengthens the maintainability of the present case. The point on merit is dealt with separately in the section on major questions of law. It must be said that the petitioner has shown very good public spirit in abiding by the wishes of Supreme Court in Balco Employees case- PIL was not meant to be adversarial in nature and was to be a cooperative and collaborative effort of the parties and the court so as to secure justice for the poor and the weaker sections of the community who were not in a position to protect their own interests by making the present petition a non-adversarial one. Response of the State & Union though is rather disheartening since they seems bent on squandering a great opportunity of making some amends in larger public good in cooperation with the petitioner as envisaged by the Supreme Court. In fact, the first Division Bench which heard the present petition had even suggested the Advocate General to advise the State Govt. to make amends but the suggestion was disregarded. 5. The question of jurisdiction arising from GVMCVs. CK Rajan (2003 7 SCC 546, para 50- 232(xi)) as raised by the State has garnered much attention. It must be noted that the obiter dictum was not delivered by the Bench in the said case instead was quoted from an earlier decision in N.B.A. Vs. Union of India (2000 SC 3751) the circumstances of which must be gone into before invoking that dictum in the present case. Supreme Court held that since High Courts do not have the powers akin to article 142 of the Constitution, they should not generally entertain the validity of a statute or statutory rule by way of a PIL. Impugned rules challenged in the present case can not be called to be a statute duly passed by the legislature or the rules made thereon, instead these rules are in the nature of an executive order issued in the name of the authority given under the provisions of Constitution which was passed by the Constituent Assembly, and not by the parliament. So, entertaining the challenge to an alleged violation of a constitutional provision is well within the jurisdiction of a High Court. In fact the term any other matter in the article 226 itself gives very wide scope of jurisdiction to a High Court. Yet it has to be admitted that apprehension of another division bench which heard this petition and mentioned the Guruvayur Devaswom case in an interim order is not completely unfounded inasmuch that the petitioner is not just sought the quashing of a particular rule or certain decisions taken by the TAC as a consequence, he has virtually challenged through the present petition a reading of a constitutional provision that has held ground since 1950 itself; theres no doubt in my mind that this case is destined for a ruling from the constitution bench of Supreme Court. 6. The question of non-joinder is in balance. While it is true that this is a question of paramount importance, the fact that respondent no.2, Secretary, ST & SC Development Department is also the ex-officio secretary of TAC, as also that it does not have a fix office or address as pointed out in the rejoinder of the petitioner almost nullifies the objection of the State. 7. The question of de-facto doctrine is an ill-founded excuse. If the very rules under which the TAC is constituted in the state is found to be ultra-vires,

and/or mala-fide, then naturally the justice is not delivered till the decisions taken on the basis of this are quashed too. As mentioned earlier, one reason why the petitioner has not challenged particular decisions is to make it a nonadversarial case of macro implications. Secondly, the state government does have the option to route all those quashed decisions through the cabinet which it should have done in the first place, instead of usurping the constitutional safeguard for tribals with the motive of preempting empowered revision of its (often brazen) decisions. Now, the recapitulation of the background of the matter of the case8. History of philosophy of Fifth ScheduleSupreme Court in the Samatha Judgement went into some detail in history of fifth schedule, relying heavily on the 1968 IIPA book of B. Shiva Rao, In Framing of Constitution. The matter was dealt with in detail earlier in Devendra Thakurs 1996 anthology, Tribal Laws and administration, as also in P.L. Mehtas 1991 book, Constitutional Protection to Scheduled Tribes in India, and has been focused on by several writers since then. The philosophy of alternate, protective governance mechanism prevalent before enactment of The Constitution could be expressed in a nutshell thus- A] Fate of tribals can not be entrusted to the legislature dominated by their immediate provincial neighbours. B] Put a judicious outsider completely in charge to ensure he doesn't have any personal stake in it; in other words an objective, empowered authority. C] Give the Governor eyes & ears of tribal sensibility. Besides formal recognition of the shift in tribal engagement policy of the government, the real cause of confusion in understanding of fifth schedule is created by the lack of clarity on the very scheme of Governor in chapter six of The Constitution. Analysis of Constituent Assembly debate on the subject clarifies that the present scheme of a nominated Governor reflects neither the recommendations of Joint Committee headed by Vallabhbhai Patel, nor the wishes of drafting committee. Further, while the provincial diarchy ended with the enactment of the Constitution, the special powers with regards to scheduled areas as were in GoI Act, 1935, remain despite the fact that the practical & moral authority to exercise these powers is gone. For all practical purposes, tribal policy of Govt. of India is a joint vision of Simon Commission and Thakkar Sub-Committee. This vision can be expressed in a nutshell thus- A] Tampering the application of general legislations in view of special needs of the scheduled areas & scheduled tribes as also finance for special development programs for these to be provided for in a swift, simple, non-elaborate manner. B] Provincial governments to own up the responsibility of closing the development gap between the scheduled areas-scheduled tribes and the general classes, and the Union to play an active supervisory role for the same. For the purpose of discourse though a more protectionist reading and implementation of fifth schedule was advocated, characterized by Nehrus Panchsheel Policy, elucidated not in an official declaration but as a foreword of a book by anthropologist and tribal affairs advisor Verrier Elwin. This gave rise to an alternate, liberal interpretation of an unclear text which is

diagonally opposite from that of the apparently nationalist framers of the text. This liberal interpretation has been gaining ground in the face of large scale dispossession of tribals in last two decades. Even the governments no longer counter the fact that tribals have bore the brunt maximum for the socalled development with the President saying as much in his Republic Dayeve address to the nation- Let it not be said by the future generations that the Indian Republic has been built on the destruction of the green earth and the innocent tribals who have been living here for centuries. The higher judiciary is consistently espousing the cause of such desperate yet wellmeaning activism at every possible opportunity. 9. History of Tribes Advisory CouncilIn the Government of India Act, 1919, the Governor had an Executive Council to assist him in his part of the provincial diarchy, the other part being the council of ministers. Members of this Executive Council were appointed by The Secretary of State upon advice of Governor-General. In a Government Order subsequent to enactment of Government of India Act, 1935, Tribes Advisory Council consisting of 12-15 tribal legislators was first provided for, to advise the Governor in discharging his special responsibility in respect of partially excluded areas, and of his role as sole legislature in respect of wholly excluded areas. The draft Constitution of 1948, based on recommendations of Thakkar Sub-Committee, had similarly given a wideranging role to the TAC and had made its advice obligatory for the Governor of the province. At the stage of debate though, drafting committee presented on 5th September 1949, a new draft which, based on altered national scenario since princely states had integrated formally with the Union, restricted the scope of work of TAC and also waived any obligation on Rajpramukh or Governor to follow its advice. This is the scheme passed by the Constituent Assembly and appears as such in the Constitution. 10. Fifth Schedule and TAC in practiceIn last decade, various committees (like the ones headed by B.N. Yugandhar2004, B.L. Mungekar-2005 and D. Bandopadhyay-2008) have expressly documented the general consensus that provisions of fifth schedule have largely remained un-implemented. Para.3- Annual reports of Governors are made by the respective state governments and therefore either sent to the Centre very late or sent together for last 2-3 years. So far, the only directive from Centre was issued in Nov.2012 for stopping the bauxite mining in Vishakhapatnam area which has not been complied to. Para.4- All 9 states having scheduled areas and 3 states having scheduled tribes population have formed TACs. Bhuria Committee Report 1995 had opined that TACs have mostly been ineffective. Many tribal legislators and representatives claim that their voice is muffled since this council too is chaired by the very chief of Council of Ministers. Notably, TAC in A.P. passed a resolution to amend fifth schedule so as to remove the basis of Samta Judgement. Since the fifth five-year plan, each working group report has advocated expanding the scope and role of TAC and it also finds place in reports of Bhuria Committee-1995 & Bhuria Commission-2004. Much confusion on this prevails created by appointment of Late Ramdayal Munda

as chairperson of Jharkhand TAC during presidents rule in 2010, and the present petition. Para.5- There are almost no instances of a Governor issuing a notification to amend or repeal any general legislation in scheduled areas under sub-para 5(1). There have been a handful of instances of Regulations being issued in various states under sub-para 5(2) but they were all in fact policy decisions of provincial government couched under this provision to avoid existing legal hindrances. Most common example of such regulation is cent percent reservation of seats for scheduled tribes in scheduled areas for class- 3 & 4 posts. Para.6 & 7- in 1976 the parliament added sub-para 6(dd) in fifth schedule to facilitate notification of more regions as scheduled areas in the same year. This amendment was challenged in Amrendranath Dutta Vs. State of Bihar case and the Supreme Court rejected the contention based on simple interpretation of para 7. Now, the major questions of law involved in the casea. Are the impugned rules made by The Governor? State had contended that these Rules were made by the Governor. Submissions of Amicus Curie and that of the Union clearly indicate that these rules were made in the name of Governor; rules formulated by the concerned department were later assented to by the Governor before publication in the state gazette. Petitioner argued in the court that any such rules made under the provisions of Fifth Schedule are to be signed by the Secretary to Governor, instead of Tribal Welfare Department, General Administration or any other government department. Since the Supreme Court has consistently held since 1997 that powers of Governor under fifth schedule are free from aid and advice of council of ministers, and as Balakrishnan, CJI., as he then was, reiterated from Amrendra Nath Dutta Vs. State of Bihar Case, in his ruling in Union of India Vs. Rakesh Kumar & Ors., it is evident that framers intent behind including the Fifth Schedule was that of a separate administrative scheme for scheduled areas in order to address the special needs of tribal communities, it is only expected that the execution-implementation mechanism will also be different and appear different; easily distinguishable. Impugned Chhattisgarh Tribal advisory Council Rules, 2006 are not made by the Governor. b. Legislative Competence for making these rules? Sub-para 4(3) of Fifth Schedule clearly stipulated the scope of the rules to be made by the Governor and altering the mandate or duties of TAC is not one of them, even if one takes a liberal interpretation of all incidental matters therein. It may be noted that State, Union and Amicus Curie all have in defending the current functioning of TAC on the basis of Suo-Motu powers, Council of Minister mechanism & constitutional stature of Chief Minister respectively, conceded the contention of petitioner that sub-para 4(2) is being violated. Now, if the TAC is expected to give advice as a pre-condition before the Governor makes any regulation as per sub para 5(5), and in doing so Governor may also amend or repeal any act of Parliament or legislature of the State or any other law, then presence of any member of council of minister in TAC is against the law of natural justice, since a minister is not merely a participantspectator in passing of such law or Act in first place but the very man (along

with colleagues in council of ministers) responsible for formulation and presenting to legislature of the same. Insofar the impugned Rules as formulated do alter the mandate of the Tribes Advisory Council. Since the question of the legislative competence is not just limited to making the rules, rather of making such rules, it is to be said that impugned Rules lack legislative competence. c. Are the functions of Governor discretionary under the Fifth Schedule? In absence of any original analysis of fifth schedule coming from eminent jurists like Basu, Jain, Seervai, Swarup-Singhai, Datar, Kashyap et al in their celebrated commentaries on Constitution, the Judiciary interpreted it in a most judicious manner. In 1969, Supreme Court dwelt for the first time on Fifth Schedule in Ram Kirpal Vs. State of Bihar case and took a line of clinical adherence to the official text, disregarding the dichotomy. Same year the Kerala High Court ruled while adjudicating in the matter of validity of Kerala Hillman Rules, 1964, that dedicated legislations for tribals can only be passed by the parliament as tribal affairs do not find mention in any list of schedule VII and are thus part of its residuary domain. Most notable ruling in this mould is that in the Shamsher Singh Vs. State of Punjab case where the very clinical reading of article 163 became the basis of two Attorneys General Soli Sorabjee (2001) and Goolam Vahanvati (2010) arriving at diagonally opposite conclusion on discretionary powers of Governor under Fifth Schedule. In 1997, in Bhuri Nath Vs. Govt. of J&K case the Supreme Court overturned the conclusion in Mansingh Surajsingh Padvi case and ruled that Governors functions under fifth schedule are discretionary. Same year in Samta case, the Supreme Court went into the official history of Fifth Schedule and its ruling for the first time went against a provincial government. Important case laws from Supreme Court: Cases related to Fifth ScheduleCases related to Governors functions in generalOther relevant casesRam Kripal Bhagat Vs. State of Bihar- (1969) 3 SCC 471 State of Meghalaya Vs. Ka Brhyien Kurkalang- (1972) 1 SCC 148 Samata Vs. State of A.P.- (1997) 8 SCC 191, para 173 Bhuri Nath Vs. State of J&K- (1997) 2 SCC 745, para 25 Satyeshwar Daolagupu Vs. Secetretary to Govt. of Assam- AIR 1974 Gau.20, 22-25 (8,10,11,16,21) Rami Reddy Vs. State of A.P.- AIR 1988 SC 1626, 35 Ramadoss G. Vs. Union- (1971) 2 Andh WR 261 Mangal Singh Vs. Union- (1973) 4 SCC, 225-318 Amrendranath Dutta Vs. State of Bihar- AIR 1983 Pat.151, 157 Edwingson Bareh Vs. State of Assam- AIR 1966 SC 1220 Amrendra Pratap Singh Vs. Tej Bahadur Prajapati- AIR 2004 SC 3782 Mahtab Patnaik Vs. State of AIR 1955 Pat.317, 319-20 Venkata Surya Sivarama Vs. State of AP- AIR 1967 SC 71 Mansingh Surajsingh Padvi Vs. State of Maharashtra- (1968) 70 Bom LR 654

Shamsher Singh Vs. State of Punjab- AIR 1974 SC 2192, (1974) 2 SCC 831 M.P. Special Police Establishment Vs. State of M.P.- (2004) 8 SCC 788 Pu Myllai Nlychho Vs. State of Mizoram- (2005) 2 SCC 92 D. Uphing Maslai Vs. State of Assam- AIR 2002 Gau 64, paras 6-8, 13-14, 1819 Regional Provident Fund Commissioner Vs. Shillong City Bus Syndicate1996(8) SCC 741, para 2-4, 9-10 2006(4) SCC 748, para 5-7 Union of India Vs. Rakesh Kumar & Ors.- 2010 (1) SC 281 Guruvayur Devaswom Managing Committee Vs. C.K. Rajan - 2003 7 SCC 546, para 50. 232(xi), 53, 60 Union of India Vs. S. Srinivasan- 2012 STPL 28(Web) 325 SC http://www.stpl-india.in/SCJFiles/2012_STPL%28Web%29_325_SC.pdf

Bibliography: Constituent Assembly Debates, Vol.VIII, 2010, Lok Sabha Secretariat http://164.100.47.132/LssNew/cadebatefiles/C30051949.html http://164.100.47.132/LssNew/cadebatefiles/C31051949.html http://164.100.47.132/LssNew/cadebatefiles/C01061949.html http://164.100.47.132/LssNew/cadebatefiles/C02061949.html Constituent Assembly Debates, Vol.IX, 2010, Lok Sabha Secretariat http://164.100.47.132/LssNew/cadebatefiles/C05091949.html

You might also like

- Francisco v. House of Representatives (Case Summary)Document6 pagesFrancisco v. House of Representatives (Case Summary)Jerome Bernabe83% (6)

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Contemporary World History Class XII (Old NCERT Must Read) PART 2 of 2Document54 pagesContemporary World History Class XII (Old NCERT Must Read) PART 2 of 2Udit Davinci Pandey67% (3)

- To It by The Governor. The Chhattisgarh High Court Ruled in The Case ThatDocument2 pagesTo It by The Governor. The Chhattisgarh High Court Ruled in The Case Thathnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Case Brief RDocument4 pagesCase Brief RsamriddhiNo ratings yet

- Doctrines Developed by The Indian Courts For Settling The Issues Related To Relationship Between Centre and StateDocument3 pagesDoctrines Developed by The Indian Courts For Settling The Issues Related To Relationship Between Centre and StateAAYUSHI SINGHNo ratings yet

- Kihota Hollohan V. Zachilhu & Ors.: Case Analysis ofDocument14 pagesKihota Hollohan V. Zachilhu & Ors.: Case Analysis ofCharu singhNo ratings yet

- NJAC Written Submission Part IDocument49 pagesNJAC Written Submission Part ILive LawNo ratings yet

- SR Bommai Vs Uoi JudgementDocument6 pagesSR Bommai Vs Uoi JudgementPOTATO GaMiNgNo ratings yet

- Arguments AdvancedDocument8 pagesArguments AdvancedNavjit SinghNo ratings yet

- "Merit" in The Appointment of Judges: by M.P. SinghDocument16 pages"Merit" in The Appointment of Judges: by M.P. SinghjananiNo ratings yet

- Legitimate Expectations, Judicial Review and TribunalsDocument29 pagesLegitimate Expectations, Judicial Review and TribunalsPratik Harsh100% (1)

- Amendability of Fundamental RightsDocument9 pagesAmendability of Fundamental RightsRajat KaushikNo ratings yet

- Judicial ReviewDocument17 pagesJudicial ReviewAnshu Sharma HNLU Batch 2018No ratings yet

- Judiciary - Class12 Unit 1Document10 pagesJudiciary - Class12 Unit 1nijo georgeNo ratings yet

- Law Essay PDFDocument2 pagesLaw Essay PDFRenata RamdhaniNo ratings yet

- Consti Midterm Pex 1Document4 pagesConsti Midterm Pex 1Honey Lorie PeterNo ratings yet

- Kesavananda Bharati v. The State of Kerala Who Wins?: Eastern Book Company Generated: Tuesday, February 7, 2017Document20 pagesKesavananda Bharati v. The State of Kerala Who Wins?: Eastern Book Company Generated: Tuesday, February 7, 2017ShadabNo ratings yet

- Judicial CreativityDocument10 pagesJudicial CreativityRajveer Singh SekhonNo ratings yet

- The Practical Lawyer PDFDocument20 pagesThe Practical Lawyer PDFSubh AshishNo ratings yet

- Digested Cases Montejo Consti 1Document12 pagesDigested Cases Montejo Consti 1Martin Martel100% (1)

- Kesavananda Bharati v. The State of Kerala Who Wins?: Eastern Book Company Generated: Tuesday, October 4, 2011Document20 pagesKesavananda Bharati v. The State of Kerala Who Wins?: Eastern Book Company Generated: Tuesday, October 4, 2011Suraaj TantraNo ratings yet

- Bhim RaoDocument49 pagesBhim RaoRitesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Imbong vs. Ochoa PDFDocument6 pagesImbong vs. Ochoa PDFNelda EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Ashish Notes 4Document9 pagesAshish Notes 4Muskan goriaNo ratings yet

- Kesavananda Bharati v. The State of Kerala Who Wins?: Eastern Book Company Generated: Wednesday, September 16, 2015Document20 pagesKesavananda Bharati v. The State of Kerala Who Wins?: Eastern Book Company Generated: Wednesday, September 16, 2015RishabhRathoreNo ratings yet

- Consti CA 1Document4 pagesConsti CA 1SakshamNo ratings yet

- Comment On ArbitrabilityDocument4 pagesComment On ArbitrabilityFar TaagNo ratings yet

- Polirev DigestDocument26 pagesPolirev DigestElaine Llarina-RojoNo ratings yet

- Kesavananda Bharathi Vs Govt of KeralaDocument20 pagesKesavananda Bharathi Vs Govt of Keralavenkatrao_100No ratings yet

- 8 PDFDocument8 pages8 PDFGILLHARVINDERNo ratings yet

- Judicial LegislationDocument9 pagesJudicial LegislationShehzad HaiderNo ratings yet

- Abakada Guro Vs ErmitaDocument29 pagesAbakada Guro Vs ErmitaMario P. Trinidad Jr.100% (2)

- Senate vs. Ermita (G.R. No. 169777) - Digest FactsDocument9 pagesSenate vs. Ermita (G.R. No. 169777) - Digest Factsaquanesse21No ratings yet

- Macalintal vs. PETDocument18 pagesMacalintal vs. PETDudly RiosNo ratings yet

- Golaknath V State of PunjabDocument15 pagesGolaknath V State of PunjabPurvaNo ratings yet

- Brief Case Analysis of State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali SarkarDocument7 pagesBrief Case Analysis of State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkarrayadurgam bharatNo ratings yet

- Remedies Against AdministrationDocument16 pagesRemedies Against AdministrationKartik KamwaniNo ratings yet

- Krishna Neel Verma v. Federal Republic of Mayeechin III: A Case Pertaining To Accepting Migrants OnDocument9 pagesKrishna Neel Verma v. Federal Republic of Mayeechin III: A Case Pertaining To Accepting Migrants OnpbNo ratings yet

- Kesavananda Bharati VsDocument7 pagesKesavananda Bharati VsSahil KhanNo ratings yet

- Admin Law (Peer Group)Document7 pagesAdmin Law (Peer Group)Shobhit BattaNo ratings yet

- Raj. Vo UoiDocument13 pagesRaj. Vo UoimeghakainNo ratings yet

- Legal English Assignment: WWW - Nja.nic - inDocument7 pagesLegal English Assignment: WWW - Nja.nic - inKalpana YadavNo ratings yet

- Basic StructureDocument20 pagesBasic Structureshankargo100% (1)

- Yaga Lakku EndsemDocument49 pagesYaga Lakku EndsemAshishNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law Project SEM IIIDocument26 pagesConstitutional Law Project SEM IIINabira FarmanNo ratings yet

- Chavez Vs Judicial and Bar CouncilDocument2 pagesChavez Vs Judicial and Bar CouncilChammy100% (1)

- Dharmashastra National Law University, JabalpurDocument8 pagesDharmashastra National Law University, JabalpurKanishka SihareNo ratings yet

- Measure For Unconstitutional MeasureDocument52 pagesMeasure For Unconstitutional MeasureKshitij Ramesh DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatuteDocument10 pagesInterpretation of StatuteIzaan Rizvi0% (1)

- State of Rajasthan v. Union of India (AIR 1977 SC 1361)Document13 pagesState of Rajasthan v. Union of India (AIR 1977 SC 1361)meghakain56% (9)

- Barium Chemicals Ltd. v. Company Law Board Article 356. State of Rajasthan v. Union of India3 Article 74Document3 pagesBarium Chemicals Ltd. v. Company Law Board Article 356. State of Rajasthan v. Union of India3 Article 74priyankaNo ratings yet

- Chavez vs. Judicial and Bar CouncilDocument74 pagesChavez vs. Judicial and Bar CouncilRico UrbanoNo ratings yet

- IV Judicial Review CasesDocument31 pagesIV Judicial Review Casesmarge carreonNo ratings yet

- Chavez vs. Judicial and Bar CouncilDocument74 pagesChavez vs. Judicial and Bar CouncilRico UrbanoNo ratings yet

- Brief On Indian Service and Administrative LawsDocument6 pagesBrief On Indian Service and Administrative LawsPrashant KhuranaNo ratings yet

- IOS ProjectDocument7 pagesIOS ProjectHritikka KakNo ratings yet

- Consti Case Gutierrez Vs HR Committee On Justice, 643 SCRA 198, GR 193459 (Feb 15, 2011)Document6 pagesConsti Case Gutierrez Vs HR Committee On Justice, 643 SCRA 198, GR 193459 (Feb 15, 2011)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- Courts and Procedure in England and in New JerseyFrom EverandCourts and Procedure in England and in New JerseyNo ratings yet

- Law School Survival Guide (Volume II of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Evidence, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Law School Survival GuidesFrom EverandLaw School Survival Guide (Volume II of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Evidence, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Law School Survival GuidesNo ratings yet

- Human Rights in the Indian Armed Forces: An Analysis of Article 33From EverandHuman Rights in the Indian Armed Forces: An Analysis of Article 33No ratings yet

- Yes Minister - Prime Minister (Typical Episode Notes)Document2 pagesYes Minister - Prime Minister (Typical Episode Notes)hnlu_subhro0% (1)

- World Development Report 2016 PDFDocument359 pagesWorld Development Report 2016 PDFZoune ArifNo ratings yet

- Guwahati - Governors PowesDocument11 pagesGuwahati - Governors Poweshnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Rejoinder in The PILDocument2 pagesRejoinder in The PILhnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Rank List Sem IXDocument5 pagesRank List Sem IXhnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Indian Express News ReportsDocument1 pageIndian Express News Reportshnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Cal - Governors PowersDocument64 pagesCal - Governors Powershnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Chhattisgarh Activists Write To The CenterDocument1 pageChhattisgarh Activists Write To The Centerhnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Career & Writing Chronology: Dr. BD SharmaDocument1 pageCareer & Writing Chronology: Dr. BD Sharmahnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- 5TH Schedule IntroductionDocument5 pages5TH Schedule Introductionhnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- 31-March 2013: Role of Governors in Tribal AreasDocument4 pages31-March 2013: Role of Governors in Tribal Areashnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Dilemma - Historical Injustice With TribalsDocument4 pagesConstitutional Dilemma - Historical Injustice With Tribalshnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- 5th Schedule DebateDocument43 pages5th Schedule Debatehnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- PIL Filed in The Bilaspur HCDocument13 pagesPIL Filed in The Bilaspur HChnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- By-BK Manish: Left and The Tribal QuestionDocument4 pagesBy-BK Manish: Left and The Tribal Questionhnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- CG HC OrderDocument13 pagesCG HC Orderhnlu_subhroNo ratings yet

- Fifth Schedule - FarceDocument6 pagesFifth Schedule - Farcehnlu_subhro100% (2)

- EVSDocument55 pagesEVSRishabhGangwarNo ratings yet

- Election Commission's ResponseDocument2 pagesElection Commission's ResponsethequintNo ratings yet

- Punjab SC AND BC Act 2006Document9 pagesPunjab SC AND BC Act 2006Sunil SharmaNo ratings yet

- PWD Volume 1Document222 pagesPWD Volume 1harishjasani67% (6)

- Dopt CpioDocument12 pagesDopt CpioadhityaNo ratings yet

- PT 365 Government Schemes 2020 PDFDocument172 pagesPT 365 Government Schemes 2020 PDFjai-shriramNo ratings yet

- GTU Regulations-2017 - 1 PDFDocument142 pagesGTU Regulations-2017 - 1 PDFAmaru GujaratNo ratings yet

- MICR CodeDocument635 pagesMICR Codemother21020% (1)

- 74tcs-Transfer-Order-Dt 02 08 18Document4 pages74tcs-Transfer-Order-Dt 02 08 18sulemanreangNo ratings yet

- DLCPM00312970000241958 NewDocument2 pagesDLCPM00312970000241958 NewAnshul KatiyarNo ratings yet

- List of Viceroys of IndiaDocument3 pagesList of Viceroys of IndiaAbdul Hakeem100% (2)

- Respondent Memo Final PrintDocument19 pagesRespondent Memo Final PrintKrusha BhattNo ratings yet

- Amartya Sen and The Nalanda Scam by Priyadarshi DuttaDocument13 pagesAmartya Sen and The Nalanda Scam by Priyadarshi DuttaSati Shankar50% (4)

- Microbiology SelectedDocument4 pagesMicrobiology SelectedGurpreetNo ratings yet

- K. Lakshminarayan v. Union of India and Ors.Document54 pagesK. Lakshminarayan v. Union of India and Ors.jay1singheeNo ratings yet

- Ifsc Code List-2001-2500 PDFDocument500 pagesIfsc Code List-2001-2500 PDFMahesh100% (2)

- Ashok GahlotDocument3 pagesAshok GahlotAbhishek JainNo ratings yet

- ch-21 Employment After RetirementDocument8 pagesch-21 Employment After Retirementkarunamoorthi_p2209No ratings yet

- NSE Centres 2015Document82 pagesNSE Centres 2015gnkstarNo ratings yet

- Mumbai SMEsDocument648 pagesMumbai SMEsVbs ReddyNo ratings yet

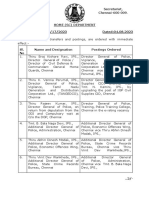

- DIPR-IPS - Transfers & Postings - Date 4.08.2023Document4 pagesDIPR-IPS - Transfers & Postings - Date 4.08.2023Raj kumarNo ratings yet

- Annex7 PDF PDFDocument14 pagesAnnex7 PDF PDFrajarao001No ratings yet

- Hindi Prachar Sabha - ResultsDocument1 pageHindi Prachar Sabha - ResultsvjaiNo ratings yet

- Directorate of Technical Education, Maharashtra State, MumbaiDocument35 pagesDirectorate of Technical Education, Maharashtra State, Mumbaijo_work2900No ratings yet

- Compendium of Accounting Classification CodesDocument525 pagesCompendium of Accounting Classification Codeskuththan0% (1)

- Delegation of Financial Powers Rules, 1978Document31 pagesDelegation of Financial Powers Rules, 1978sairam dulipudiNo ratings yet

- Sbi 1024Document5 pagesSbi 1024Priyanka SharmaNo ratings yet

- CV Vivek Mishra SQSDocument4 pagesCV Vivek Mishra SQSvasaganeshNo ratings yet

- Pet Aso-ADocument2,620 pagesPet Aso-AAshutosh KashyapNo ratings yet