Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J Chadwick - Museums in Society

Uploaded by

Caroline Alciones LeiteOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J Chadwick - Museums in Society

Uploaded by

Caroline Alciones LeiteCopyright:

Available Formats

Museums in Society

Pgina 1 de 8

Museums in Society

John Chadwick, 1995-1996

This paper was written for a Language, Literacy, and Culture classs at the University of New Mexico during the Fall, 1995 semester. This paper was not intended to be the definitive work on the history of museums, but rather an attempt to explore where museums have been and where they may be going. In light of some of the controversy surrounding multiple voices in our cultural institutions this paper is taking on some new meaning for me.

Introduction

Since the Transcendentalist movement led by Ralph Waldo Emerson in the 19th century, and reinforced by the Humanistic movement in the early 1900s, Unitarians have largely avoided using the Bible in worship and religious education. Now, Unitarian minister Tony Larsen tells his fellow makes a claim, which rings true, that we are cultural Christians and to fail to teach our children about the Bible leaves them culturally illiterate. Literacy is more than writing and language skills, it is at the root of culture. It seems to be stating the obvious, but we live in a heterogeneous society where it is important to learn the culture of the society. I believe that everyone should have their voice represented, but it is equally as important to understand the voices of others in our society as well. The notion of cultural literacy is something that drives me and many other museum professionals. There is an ideal that we are doing something good for society by protecting, preserving, and interpreting cultural artifacts and the stories behind those artifacts. This ideal often comes into conflict with political realities as the controversy surrounding the Enola Gay exhibition at the Smithsonian played out on the evening news. The exhibit, part of the 50th anniversary of the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, was perceived by some stakeholders, notably members of Congress, as a commemoration. The curators viewed the exhibit as an opportunity to explore all the factors that were weighed in making the decision to drop the bomb. The dichotomy that arose brought to the public the debate that often takes place behind closed walls, the process that goes into designing an exhibit that helps visitors gain a deeper understanding of an artifact. In the case of the Enola Gay, the attempt was made to help the public gain a deeper understanding of the issues rather than to present an airplane in an exhibit hall. This personal research project has allowed me to read books by several noted authors in the museum profession and build my personal philosophy. Even after the reading I am more convinced than ever that the museum profession needs people who will fight the good fight from the inside rather than the outside. Stephen E. Weil has been the deputy director of the Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Gardens, Smithsonian Institution, since 1974. Weil takes a very critical view of the role of museums in society in his 1995 book A Cabinet of Curiosities : Inquiries into Museums and their Prospects. Weil writes: "Unlike medicine, the law, and certain other professions that offer the opportunity for individual practice and that may provide occasions for courageous resistance, museum work occurs almost exclusively in an institutional setting. Courage is rarely an institutional quality. Consider, for example, the case of history museums. If history, (as one historian has called it) is the 'gossip of winners,' should it be a surprise that the versions of history offered by such museums may tend to change almost precisely in tandem with any change in those winners? The very notion of institutional bravery would appear to be something of an oxymoron." This really begs the question of whose history, and whose culture are we presenting in a museum. A

mhtml:file://C:\Users\Luiz Srgio\Desktop\Museus de arte_sociedade e democracia\...

23/03/2009

Museums in Society

Pgina 2 de 8

little understanding of why governments and other political bodies created museums can go a long way in helping to understand how we got to where we are. Just who are the winners, and what is the gossip we are telling ourselves. It is virtually impossible to be totally objective, as humans we all have opinions, and museums make value judgements about what is important when they spend millions of dollars on developing exhibits.

Birth of the Museum

To understand how museums came to be, it is important to remember that museums are primarily collections-based organizations. That is to say, museums are designed around their collections. The collection may be art, history, anthropology, or natural history, but a museum is designed around a collection. One only need to look at one of the newest natural history museums in the world, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque. The legislation enabling the museum defines the mission as to protect, preserve, and interpret the natural history and resources of the state of New Mexico. The idea for the museum was the result of paleontologists who were upset that the dinosaur finds in New Mexico were being sent out of state, and the state needed a resource to keep these fossils in the state. As collections-based institutions, many museums are associated with research facilities such as universities with public displays often being only the visible portion of what a museum does. The idea of a public museum really didnt take off until the 19th century. According to Michael M. Ames (1992), director of the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia since 1974, The granting of public access therefore also entailed the granting of a degree of public control over the museum enterprise, the purpose of the institution, and the collections it contained. This control was founded on the expectation that publicly owned collections would be made meaningful to the public. Thus, gradually, the public -- or more correctly, the educated classes -- came to believe that they had the right to expect that the collections would present and interpret the world in some way consistent with the values they held to be good, with the collective representations they held to be appropriate, and with the view of social reality they held to be true. Once again we see a theme starting to emerge, that history is the gossip of the winners and as museums came to be open to the public, the concept was not a noble social issue as much as a matter of control. From Tony Bennetts book The Birth of the Museum (1995), makes a case for the development of the modern museum concept as a process that acquired recognized form in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Both Ames and Bennett make the claim that the evolution of the museum occured in response the transfer of cultural holdings from the private sector to the public sector in the nineteenth century. However, according to Bennett, the idea of a public good was more social control than social good. It is, however, only later -- in the mid to late nineteenth century that the relations between culture and government came to be thought of and organized in a distinctively modern way via the conception that the works, forms and institutions of high culture might be enlisted for this governmental task in being assigned the purpose of civilizing the population as a whole. Museums and other cultural institutions were viewed as a means to cure social ills of the day such as alcoholism, but, no matter how noble, the issue was control, for the dominant culture to pass their culture and values to the subordinate classes.

Cultural Capital

The concept of cultural capital is really nothing new, it is an expansion of the theme that history is the gossip of the winners. It is also a denigration of culture, from something that everyone has to a commodity to be attained, something that can be bought, and sold. Borrowing from the work of fellow Englishman Nick Merriman and French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, Kevin Walsh (1992) explores the role of museums in the post-modern world. Walsh writes, "Ones 'cultural capital', a form of distinguishing kudos, is articulated through the consumption of cultural products; it thus goes through a process of incrementation with each product consumed. This process of cultural capital investment serves to distinguish the individual from one social group, whilst at the same time

mhtml:file://C:\Users\Luiz Srgio\Desktop\Museus de arte_sociedade e democracia\...

23/03/2009

Museums in Society

Pgina 3 de 8

developing and image of association with another group, usually one perceived as being elevated from that which the individual is attempting to remove themselves." We seem to be building social classes based not on ethnicity or income, but on the cultural capital one group may be peceived as possessing. I really shouldnt be shocked though, Ames and other Canadian researchers have been say for years that one of the reasons some people go to a museum is just to be seen at the museum. The demographics of who visits museums, which I will discuss later, would seem to support the notion that some people would want to be seen as part of the leisure class that has the time, money, and resources to attend museums and other cultural institutions and events. Weil speaks of the metaphors we use to describe museums. The metaphors we use define the role of the museum professional and define how the public views the museums. According to Weil, To call a museum a temple is to summor up a rich mixture of powerful suggestions. It might suggest, for example, that those of us who work within its precincts are performing some kind of priestly function. It certainly suggests that the attitude most appropriate for visitors to the museum is one of reverence. Above all, it suggests that the museum objects toward which that reverence is due may, in some manner, partake of the sacred. The idea of the museum as a the keeper of the sacred trust of society, and curators as the guardians, has certainly created an image of the museum that keeps many people away, even while may museum professionals are working hard to draw in the disenfranchised and give them a voice that becomes part of the museum collections and holdings. But, metaphors, like myths, die hard -- perhaps just as religions hold some myths to be absolute fact or truth, some museum professionals still cling to old metaphors. Weil continued, The metaphors we elect to use in speaking about our museums can directly influence what our visitors expect. Call a museum a treasure house, and their expectation may be of carefully chosen objects of great rarity and value. Call it instead a laboratory for the visual arts and what they may expect instead is the unusual, the novel, the experimental. Compared with the museum as temple, the museum as laboratory is a place where truth and beauty are to be discovered not through revelation but through patient trial and error. In a laboratory, not everything need be right. Research replaces reverence, an inquisitive spirit replaces faith. The institution we imagine is a completely different and far more intellectually driven one than either the museum as temple or the museum as treasure house. As my friend Kris Morrissey is fond of telling audiences at museum conferences, the notion that the museum is not Oz, and the curator is not the great wizard is at the heart of the application of constructivist learning philosophy to the museum. Science Centers such as the Exploratorium in San Francisco have begun to transform the concept of the museum to that of laboratory that is both fun and messy. Learning is by orderly trial and error and discovery. Science Centers are, in many ways, what John Dewey and other progressive educators envisioned as the model school, students working together on authentic problems. We need to move away from the notion of museums as brokers of cultural capital. As Weil and others point out, institutions are tied both to their mission and to those who pay the bills. Institutional bravery is a real oxymoron. This does not get us off the hook though, we must try and we must be aware of our limitations as museum professionals. As Weil eloquently points out: Just as one culture is necessarily distorted when seen through the lens another -- there is a good optical metaphor -- so is the past distorted when seen through the lens of the present. Those, though, are only two of our difficulties. A third is that every story must be somebodys story. Once upon a time -- in the time of our grandparents or certainly of our great-grandparents -- people still believed in what one writer has called 'the certainty of an ultimately observable, emprically verifiable truth. We no longer do. As people who live in this world, we cannot discuss it with the detachment of somebody who lives outside it. No matter how earnestly any storyteller purports to tell us a story truthfully, we understand how deeply the story that is told must be biased from the start by his or

mhtml:file://C:\Users\Luiz Srgio\Desktop\Museus de arte_sociedade e democracia\...

23/03/2009

Museums in Society

Pgina 4 de 8

her point of view. Moreover, because such a narrator -- no more than the observer who interacts with a museum object -- can never be fully detached or free but must always function from within a specified social context, then even the most purportedly truthful story must, in turn, be profoundly influenced by the nature of the social context. Like the meanings that adhere to our objects, the stories that we tell in museums turn out to be, at bottom, social constructs. The more I meditate and reflect on the above statement, the more powerful it becomes, and the feeling of hopelessness dissipates. We need to be honest with ourselves about what we are doing in museums. We are telling stories that are colored by our own perceptions.

Shifting Role of Museums

Museums are becoming recognized as educational organizations. Often thought of as informal learning environments because the education is not alway direct or overt, museums are increasingly borrowing tools from more formal educational organizations while formal educational organizations are learning from museums. The line of distinction between informal and formal education is breaking down, and I contend that much of it is due to computer-based technology. Stephen Weil laments that when museum professionals gather we more often cary on about how wonderful the shift is to educational programs as the new focus for our institutions without asking really hard questions. Failure to ask hard questions and formulate answers among ourselves could result in the withdrawal of funding. Remember, museums are non-profit institutions and as such must answer to the various funding sources. According to Weil, museums are, and always will be collections-based organizations and by defining ourselves by our educational mission rather than our collections leaves us vulnerable to massive cuts as politicians. Weil states, More troubling in this respect is the extent to which some museums have begun to stress general educational objectives as the principal outcome for which they ought to be valued. By doing so, they may ultimately leave themselves vulnerable to the claims of more traditional educational institutions that these latter could, with only a little inexpensive tinkering, deliver comparable value at a fraction of the cost. In a paper and presentation I made at the Visitor Studies Conference held in July, 1995 in St. Paul, Minnesota, I discussed the move by museums towards providing online services. In the paper I wrote, Museums are educational organizations with missions that define what topics they present to the public. Museums are already engaged in the business of distance education. Distance Education is a way of delivering instruction to an audience that is separated from the source of the instruction. Technical media may be as simple as a handout or a text panel or as complex as an interactive multimedia program linked to the Internet. Meetings may take place through contact with docents or lectures by educators or curators. It is important to realize in this discussion about the use of the Internet as a means to deliver instruction that distance education is not just technology. We like to adapt a less rigid definition of distance education than Mason and Kay (1990) and their six point criteria to determine if instruction falls in the category of distance education. Their model is better suited for formal educational settings. However, there are four characteristics of distance education that apply to museums; the separation of teacher and learner (by time and/or space), influence of an educational organization, the use of technical media, usually print, to unite teacher and learner, and the possibility of occasional meetings. Visitors may be separated from those who develop exhibits by time and/or space. As museums continue to evolve and offer more educational programming, I see telecommunications playing a vital role. Museums do have the power to excite and engage learners, and the learning is voluntary. People are not compelled to attend museums, and observing how visitors behave in museums, they will stop and pay attention at objects or exhibits of personal interest.

mhtml:file://C:\Users\Luiz Srgio\Desktop\Museus de arte_sociedade e democracia\...

23/03/2009

Museums in Society

Pgina 5 de 8

Bennett, citing the work of Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, claims that French museums were born from the French Revolution, exposing what had been concealed by the upper classes. Appropriating royal, aristocratic and church collections in the name of the people, destroying those items whose royal or feudal associations threatened the Republic with contagion and arranging for the display of the remainder in accordance with rationalist principles of classification, the Revolution transformed the museum from a symbol of arbitrary power into an instrument which, through the education of its citizens, was to serve the collective good of the state. While it sounds noble that the people are reclaiming their heritage, I am concerned again about the notion of history is the gossip of the winners where there are only new winners ready to repress. Bennett argues that there is a mismatch between the rhetoric of the stated aims of the museum and the political rationality of the governments that provide the bulk of the funding for many museums. This conflict is an ever present feature of museums, and the goal for me, as a museum professional, is to recognize the conflicts and be able to do my job with a level of ethics and morals that ensure that I am really an agent for change rather than perpetuating a dominate and often times repressive culture.

Why People Visit a Museum

Peter Vergo edited a book titled The New Museology, a series of essays exploring museums in society in Great Britian. Nick Merriman (1989) explored the issue of who visits the museums and discovered what researchers in Canada had discovered, that frequent or regular visitors, ...tend to be of high status, to have received tertiary education, and to be students or in work while those who rarely or never visit museums tend to be the elderly, those of low status, to have left school at the earliest opportunity, and to be looking after the home, or in retirement. Weil spoke of the power of metaphors, and the metaphors and resulting image from the 19th century museum still continues. In a survey, Merriman found that, The more frequently respondents visit museums, the more likely they are to associate it with a library; the less frequently they visit, the more likely they are to associate it with a monument to the dead. Either metaphor does little to encourage people in a free society to visit the museum unless there is a strong interest in a particular topic. Citing the work of Pierre Bourdieu, Merriman says: Bourdieu argues that one effect of schooling is to produce a culture of consensus, by which the maintenance of hierarchical social relations is (mis)recognized as natural and legitimate by all classes. He argues schooling imposes an arbitrary set of values (arbitrary in the sense that they are not fixed or resident in nature) in favour of the dominant class. Because school has the illusion of neutrality this arbitrary set of values is misrecognised as legitimate and natural. Thus the school inculcates both a recognition of the legitimacy of the dominate culture -- and of the illegitimacy of the culture of the dominated -- and a misrecognition that the dominate culture is an arbitrary construction. Merriman says, Just as with school, therefore, the museum and the works in it are understood best by those who are predisposed by their habitus to acquire the cultural competence to do so. Those in possession of the competence to render art and the experience of the art gallery meaningful feel at home in the museum and know how to behave there. For those less well-equipped, misunderstanding and confusion are inevitable. Bourdieus work is criticized by Merriman for looking only at the social function of museums and ignoring the psychological factors involved in museum attendance, just as he criticize the work American museum professionals for not looking closely at the social function of museums. Merriman has articulated that visiting museums is as much a social function as a psychological function for personal growth and education.

Discussion

mhtml:file://C:\Users\Luiz Srgio\Desktop\Museus de arte_sociedade e democracia\...

23/03/2009

Museums in Society

Pgina 6 de 8

Through this paper I have tried to explore the evolution of museums, and how museum professionals and the public view museums. The primary concern for me is culutural literacy, what does it mean to be literate without being repressed or indoctrinated. As Tony Larsen tells Unitarians that we need to have an understanding of the Bible to be culturally literate, culturally literate does not mean indoctrination or repression. It means, to me, a basic understanding of the culture and the society in which we live. My concern is about culture, and whose culture do we represent in museums. While many small museums and historical societies in small, homogeneous towns across American never have to answer these questions, larger museums must learn to play a balancing game between the political realities of funding sources, giving all a voice, and the demands of those who come to museums. Museums have also have to combat the image that they are only for those with either high income or high educational levels. Last week a message posted on Museum-L, an Internet discussion group for museum professionals, brought the issue of whose culture and the role of museums in society to a political reality for one professional:

---------------------- Information from the mail header ----------------------Sender: Museum discussion list Poster: Redding Museum of Art & History Subject: Use of Museums for Political Agenda ------------------------------------------------------------------------------We had an incident last Saturday at our museum. In conjunction with our current exhibition "Ancestral Memories: A Tribute to Native Survival", a local native American man was scheduled to have a storytelling session in the gallery. The fact that this event was scheduled by the museum on the Thanksgiving weekend was no accident -- it was felt that it would provide another local perspective on what we have to give thanks for, not to mention an antidote for the stereotyping of local native peoples around this time of year. Indeed, the entire exhibition is intended to challenge just these stereotypes, and to present native peoples in a contemporary light as living, breathing and fully functioning members of our society. Too many of our school tours brought embarrassing facts about these stereotypes to the forefront, as illustrated by an eight-year old's questioning the authenticity of a native American docent by stating "if you are a real Indian, then where are your feathers?" But I digress. On Saturday, the man, a tribal elder, came as scheduled to the museum accompanied by his wife, also an elder. The man began his talk, weaving his life experiences with his perspective on where the world is going. After about twenty minutes of intriguing stories, his wife stood and gave an extremely emotional outpouring of some of the indignities that she and her people had suffered, and continue to suffer, at the hands of the intruders to her homeland. This tearful outpouring had its intended effect on most of us in the audience of around fifty - some were also crying. One woman and her two sons (around 12 and 15 years old) left at this point. The storyteller then once more picked up the thread of his stories of visits by UFOs and prophecies, the Bible and similarities between world religions, even some comments about the Biosphere project in Arizona. Afterward, nearly everyone stayed to speak informally with this couple who had come to share their Saturday with us. The following Tuesday, I was called by the woman who had left with her sons. She was well-spoken and polite as she informed that she did not think that the museum was an appropriate place for a "furthering of one's political agenda." She was talking about the man's wife's outpouring. The woman went on to claim that she had brought her sons to a "storytelling", and was extremely disappointed in the "false advertising by the museum".

mhtml:file://C:\Users\Luiz Srgio\Desktop\Museus de arte_sociedade e democracia\...

23/03/2009

Museums in Society

Pgina 7 de 8

I (also politely) informed her that I thought the museum was a perfect place for this day's activity, and questioned the use of the term "political agenda". I told her that had she stayed, she might have been able to see the day's activity in perspective, rather than reacting to the elder woman's five minute speech. The productive period after the session, when the public mingled informally with the couple, was perhaps the most gratifying event of the day. The caller and I agreed to disagree on the use of museums as political platforms, and also on the definition of "storytelling"... Anybody have any similar experiences?

OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE ARE MINE, \\|// NOT THOSE OF RMAH! { @ @ } ---------------------------------------------oO) -{~}- (Oo-----------Jim Gilmore, Curator of Public Programs & Exhibitions Redding Museum of Art & History PO Box 990427, Caldwell Park Redding,CA 96099-0427 redmuse@shastalink.k12.ca.us 916)243-8801 fax 916)224-8929

Museum Home Page:http://www.shastalink.k12.ca.us/www/rmah/RMAHmain.html

There is hope for the museum profession when I see issues like this discussed. How do we give voice to all cultures in this country that is supposed to be the great melting pot. Unfortunately, this great melting pot has seemed to create a layer that has floated to the top and the top is more concerned about staying there and keeping the rest down rather than allowing all to have an equal voice. Museums are appropriate places to allow all to have a voice. It has been said that freedom of the press is free to those who have a printing press, and cultural representation is available to those who have museums. Here in New Mexico we have had a debate raging over state funding of the Hispanic Cultural Center. Some see it a waste of money while others see it as the only way to allow Hispanics to show history through their eyes. If we lived in an ideal world, I would side with the former, but we dont. Understanding Hispanic culture is important to understanding New Mexico, and the Hispanic Cultural Center is a appropriate venue for this. Afterall, if Minneapolis can have a Swedish cultural center, why shouldnt New Mexico have an Hispanic Cultural Center. There are other ways to allow visitors to have a voice, and technology is providing the means at the Art Gallery of Ontario. At AGO Douglas Worts provides paper and pencils and visitors to one of the galleries are invited to draw pictures and write notes about their reaction to the art in the exhibit. Many of the drawings and notes are then scanned into a computer program and the computer program is available to all visitors to the gallery. Visitors see the art and the reactions by other visitors. With the use of the Internet and access to a large variety of information sources, many teachers and museums are encouraging programs such as Kids as Curators and Students as Curators. These online projects are expanding the traditional notions of curator and gallery and providing people with a voice. But, as Jim Gilmore discovered, giving voice to members of a culture that has long been dominated can make some people uncomfortable. I find hope for museums when only one person felt uncomfortable. Which gossip will be the official story is going to be an ongoing debate in a heterogeneous society. A debate which can be divisive and brutal. As a museum professional, I need to be aware. During the course of the class someone mentioned the idea that literacy is not liberating. I would suggest that cultural literacy is not liberating either. To be culturally literate demands that we have at least a

mhtml:file://C:\Users\Luiz Srgio\Desktop\Museus de arte_sociedade e democracia\...

23/03/2009

Museums in Society

Pgina 8 de 8

passing knowledge of all the cultures that make up out society. Museums are political institutions with agendas that are set in response to political realities. Recognizing this, it is incumbent upon museum professionals to find language and metaphors that can help us transcend the gossip of the victors and included all voices in our society. There are many issues that museums and museum professionals must deal with. Understanding who are visitors are is a growing field, and one that I think is critical to the survival of museums. We have much work to do if we are to grow beyond limiting metaphors and become dynamic places where real learning can take place and everyone has a voice. I do not know the answers, but I hope I can continue to ask the questions and search for a better way of doing things.

Bibliography

Ames, M. M. (1992). Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes : The Anthropology of Museums. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. 212 pp. Bennett, T. (1995). The Birth of the Museum : history, theory, politics. New York: Routledge. 279 pp. Chadwick, J.C. and Lawicki, K.A. (in press). Evaluating On-Line Programs. From the proceedings of the 8th Annual Visitor Studies Conference, July 20 to 22, 1995, St. Paul, MN. Merriman, N. (1989). Museum Visiting as a Cultural Phenomenon. In The New Museology, Peter Vergo, ed. London: Reaktion Books, Ltd. 149-171. Walsh, K. (1992). The Representation of the Past : Museums and heritage in the post-modern world. New York: Routledge. 204 pp. Weil, S.E. (1995). A Cabinet of Curiosities : Inquiries into Museums and their Prospects. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. 264 pp.

mhtml:file://C:\Users\Luiz Srgio\Desktop\Museus de arte_sociedade e democracia\...

23/03/2009

You might also like

- How The United States Funds The ArtsDocument33 pagesHow The United States Funds The ArtsCaroline Alciones LeiteNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Museum VisitsDocument20 pagesFactors Influencing Museum VisitsCaroline Alciones LeiteNo ratings yet

- Counterfeit MuseologyDocument16 pagesCounterfeit MuseologyCaroline Alciones LeiteNo ratings yet

- Pride and Prejudice PDFDocument479 pagesPride and Prejudice PDFIqra ButtNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Basketry Teachers Resource PackDocument31 pagesBasketry Teachers Resource Packninxninx100% (1)

- Media and Information Sources: Lesson 5Document36 pagesMedia and Information Sources: Lesson 5Vinana AlquizarNo ratings yet

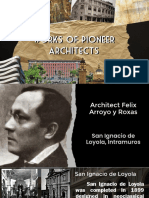

- Works of Pioneer Architects PDFDocument23 pagesWorks of Pioneer Architects PDFKimNo ratings yet

- Colorado Heritage Magazine - Summer 2018Document36 pagesColorado Heritage Magazine - Summer 2018History ColoradoNo ratings yet

- Oop C++ Book Solution All Mcq's PDFDocument37 pagesOop C++ Book Solution All Mcq's PDFmitranNo ratings yet

- Greek Medicine From Hippocrates To Galen. Selected PapersDocument423 pagesGreek Medicine From Hippocrates To Galen. Selected PapersAntonio Lopez Garcia100% (3)

- Sabah Malaysian Borneo Buletin May 2008Document28 pagesSabah Malaysian Borneo Buletin May 2008Sabah Tourism Board100% (2)

- Wayne. C FileDocument23 pagesWayne. C Filegauravb46No ratings yet

- Media Release - Jim Harper Invests in Foxton - March 2013Document3 pagesMedia Release - Jim Harper Invests in Foxton - March 2013api-211792679No ratings yet

- Bibliography of Tu 00 Ash B RichDocument160 pagesBibliography of Tu 00 Ash B RichDaniel Álvarez Malo100% (1)

- Portable Antiquities Annual Report 2001/02 - 2002/03Document74 pagesPortable Antiquities Annual Report 2001/02 - 2002/03JuanNo ratings yet

- WiX TutorialDocument63 pagesWiX Tutorialr0k0t100% (4)

- NunitDocument19 pagesNunitmarlondavidgNo ratings yet

- Modals: Can, Could, Be Able ToDocument9 pagesModals: Can, Could, Be Able Toinyric50% (2)

- Understanding Edward Hopper's Lonely Vision of America, Beyond "Nighthawks" - ArtsyDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Edward Hopper's Lonely Vision of America, Beyond "Nighthawks" - ArtsySpam TestNo ratings yet

- Expressive Self Portrait Clay Bust Project DescriptionDocument6 pagesExpressive Self Portrait Clay Bust Project Descriptionapi-233396734No ratings yet

- The Enamels of Lilyan Bachrach On Modern Silver Marybeth Schon Modern Silver Magazine 2003Document9 pagesThe Enamels of Lilyan Bachrach On Modern Silver Marybeth Schon Modern Silver Magazine 2003Robert BachrachNo ratings yet

- Basel & Architecture - Information GuideDocument5 pagesBasel & Architecture - Information GuidesusCitiesNo ratings yet

- Sample Program For Foundation DayDocument2 pagesSample Program For Foundation DayVictoria Tamayo100% (2)

- Document Control-SOPDocument2 pagesDocument Control-SOPnivil_thomasNo ratings yet

- Murach CatalogDocument3 pagesMurach Catalognishantk1No ratings yet

- J-Sketch User Manual EngDocument84 pagesJ-Sketch User Manual EngFandy MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Sad Lab PracticalsDocument26 pagesSad Lab PracticalsykjewariaNo ratings yet

- Anatolia Libraries - Catalog Help GuideDocument19 pagesAnatolia Libraries - Catalog Help GuiderichbocuNo ratings yet

- Matem Financ - J Rodriguez Franco - E C Rodriguez Jimenez Ed Patria 201401 (Cap 4 Interés Compuesto)Document38 pagesMatem Financ - J Rodriguez Franco - E C Rodriguez Jimenez Ed Patria 201401 (Cap 4 Interés Compuesto)Nadia MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- WASP Newsletter 11/01/75Document32 pagesWASP Newsletter 11/01/75CAP History Library100% (1)

- Binder 1Document169 pagesBinder 1Sayar GyiNo ratings yet

- Adès, Dawn. Constructing Histories of Latin American Art, 2003 PDFDocument14 pagesAdès, Dawn. Constructing Histories of Latin American Art, 2003 PDFLetícia LimaNo ratings yet

- AisrmyersreferenceDocument1 pageAisrmyersreferenceapi-196258509No ratings yet

- History and Narrative in Wide Sargasso SeaDocument17 pagesHistory and Narrative in Wide Sargasso Seadevilguardian34No ratings yet