Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Qualitative Exploration of Reasons For Poor Hand Hygiene

Uploaded by

Marsha WilliamsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Qualitative Exploration of Reasons For Poor Hand Hygiene

Uploaded by

Marsha WilliamsCopyright:

Available Formats

infection control and hospital epidemiology

may 2009, vol. 30, no. 5

original article

A Qualitative Exploration of Reasons for Poor Hand Hygiene Among Hospital Workers: Lack of Positive Role Models and of Convincing Evidence That Hand Hygiene Prevents Cross-Infection

V. Erasmus, MSc; W. Brouwer, MSc; E. F. van Beeck, MD, PhD; A. Oenema, PhD; T. J. Daha; J. H. Richardus, MD, PhD; M. C. Vos, MD, PhD; J. Brug, PhD

objective.

To study potential determinants of hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers in the hospital setting.

design. A qualitative study based on structured-interview guidelines, consisting of 9 focus group interviews involving 58 persons and 7 individual interviews. Interview transcripts were subjected to content analysis. setting. Intensive care units and surgical departments of 5 hospitals of varying size in the Netherlands. A total of 65 nurses, attending physicians, medical residents, and medical students. participants.

results. Nurses and medical students expressed the importance of hand hygiene for preventing of cross-infection among patients and themselves. Physicians expressed the importance of hand hygiene for self-protection, but they perceived that there is a lack of evidence that handwashing is effective in preventing cross-infection. All participants stated that personal beliefs about the efcacy of hand hygiene and examples and norms provided by senior hospital staff are of major importance for hand hygiene compliance. They further reported that hand hygiene is most often performed after tasks that they perceive to be dirty, and personal protection appeared to be more important for compliance that patient safety. Medical students explicitly mentioned that they copy the behavior of their superiors, which often leads to noncompliance during clinical practice. Physicians mentioned that their noncompliance arises from their belief that the evidence supporting the effectiveness of hand hygiene for prevention of hospital-acquired infections is not strong. conclusion. The results indicate that beliefs about the importance of self-protection are the main reasons for performing hand hygiene. A lack of positive role models and social norms may hinder compliance. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30:415-419

Hospital-acquired infections are a major threat to patients and place a great burden on national healthcare services.1,2 This problem must be combated with an adequate level of hand hygiene compliance, which is of crucial importance in preventing cross-transmission3-5 and has been identied as a health policy priority.1,6 However, the level of hand hygiene compliance remains low worldwide, and it was termed unacceptably poor by a public health authority in London, United Kingdom.7 Interventions aimed at improving hand hygiene compliance have been implemented, but the effects of these interventions remain modest and/or of short duration.8,9 To develop interventions with more-pronounced and sustainable effects, information is needed on the behavioral determinants of hand hygiene compliance.10 This topic has only recently started receiving attention by investigators involved in hand hygiene

research.11,12 Qualitative research can provide valuable insight into possible behavioral determinants13,14 and is often the rst step in a stepwise approach to intervention development.15 Qualitative methods have, however, rarely been used to evaluate hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers. Compliance with hand hygiene among different groups of hospital workers may be inuenced by beliefs and norms that vary across the groups. Review of the international literature reveals that the hand hygiene behavior of nurses has been studied most extensively.16,17 Physician compliance is often found to be lower than that of nurses,18,19 although the reason for this is not always clear. Medical students hand washing behavior has rarely been studied,20 although research into their behavior could provide essential knowledge on how tomorrows physicians could be stimulated to comply with hand hygiene guide-

From the Departments of Public Health (V.E., W.B., E.F.v.B., A.O., J.H.R.) and Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (M.C.V.), University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Dutch Society for Hygiene and Infection Prevention in Healthcare, Leiden (T.J.D.), and the EMGO Institute, Amsterdam (J.B.), the Netherlands. Received August 20, 2008; accepted December 4, 2008; electronically published April 2, 2009. 2009 by The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. All rights reserved. 0899-823X/2009/3005-0002$15.00. DOI: 10.1086/596773

416

infection control and hospital epidemiology

may 2009, vol. 30, no. 5

lines and thereby break the cycle of poor physician hand hygiene.2 The present study is a qualitative exploration of reasons for poor hand hygiene compliance among nurses, medical students, and physicians in the hospital setting in the Netherlands.

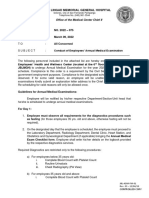

table. Topics Covered to Lead Focus Group Discussions and Interviews Topic, discussion point(s) Attitudes What are reasons for (non)compliance? What are (dis)advantages of hand hygiene? Who benets from hand hygiene? How important is hand hygiene? When do you like to perform hand hygiene? Subjective norms How do other healthcare workers inuence hand hygiene behavior? Perceived behavioral control Does anything prevent healthcare workers from performing hand hygiene? How could hand hygiene be stimulated?

methods

Participants A total of 9 focus groups and 7 individual interviews were conducted with healthcare professionals. Participants were recruited from 5 Dutch hospitals. The hospitals included were 1 small general hospital (!400 beds), 1 large general hospital (1400 beds), 1 top clinical teaching hospital (1400 beds), and 2 university teaching hospitals (1400 beds each). Participants worked in the intensive care unit (ICU) or surgical ward of these hospitals. Twenty-four participants were non-ICU nurses, 23 were ICU nurses, 4 were attending physicians, 3 were residents, and 1 were medical students. All focus groups were homogenous with respect to profession and hospital. To ensure maximum levels of participation, the focus groups and individual interviews were held on location. The individual interviews were conducted with physicians, because their schedules did not allow focus group participation. Focus Group Interviews The 9 focus group interviews took 3060 minutes and included 410 participants. All interviews were led by a moderator (V.E.) and were supported by an assistant. At the start of the interview, it was emphasized that the interview was not a test (ie, that there were no good or bad answers) and that all opinions were respected. Furthermore, the participants were encouraged to discuss their opinions openly, to increase the diversity of perspectives. All focus groups were recorded with a voice recorder and were fully transcribed. Face-to-Face Interviews The 7 face-to-face interviews took 2050 minutes. All interviews were led by an interviewer (V.E.). Again, it was expressed during the introduction that the interview was not a test and that all answers and information were useful. All interviews were also recorded with a voice recorder and were fully transcribed. Structured-Interview Guide All interviews were conducted in accordance with a structured-interview guide, to ensure that all topics of interest were covered during the interview (Table). The interview guide was developed a priori on the basis of the constructs included in an established behavioral determinants model known as the Theory of Planned Behavior.21 Therefore, the interview guide aimed to explore attitudes (ie, perceptions of different positive and negative consequences of hand hygiene compliance), subjective norms (ie, the perceived opinion of others concerning hand hygiene compliance), and perceived behav-

ioral control concerning compliance with hand hygiene standards. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, these constructs predict the intention for engagement in the behavior under study, and readiness to change hand hygiene behavior was also explored. The Theory of Planned Behavior has been used in previous studies to explain hand hygiene behavior.12,16 Earlier studies have indicated that perceived social inuences other than subjective norms, such as examplesetting behaviors by others (ie, modeling) and direct social support, may be important for a range of behaviors15; these potential social inuences were also included in the interview guide. Analysis Interview transcripts underwent systematic content analysis for collection of qualitative data, using Nvivo software, version 7. After content analysis, data were assigned codes, and code-specic reports were generated to detect common themes and key points. Content analysis was performed independently by 2 researchers (V.E. and W.B.). Disagreements were resolved by a third researcher (J.B.).

results

All participants admitted that noncompliance to the hand hygiene guidelines at their respective institutions occurred frequently. Attitudes Advantages of hand hygiene compliance. Participants mentioned that prevention of cross-infections is the main advantage of hand hygiene. Participants in all 3 groups distinguished between preventing cross-infections among patients and protecting themselves. Physicians mainly mentioned the protection of the patient on both individual and ward level as important advantages of hand hygiene, whereas nurses and medical students primarily mentioned self-protection. Fur-

poor hand hygiene during hospitalization

417

thermore, physicians and nurses mentioned the advantages of uniformity in procedure for the hospital as a whole. If participants were asked to provide reasons for performing hand hygiene, the most frequently given reasons were the protection of oneself from cross-infection (Yes, I think that most people do it for themselves. Otherwise, you wouldnt feel the urge to wash your hands so quickly after that diabetic foot [comments by a medical student]) and the need to feel clean and fresh after performing tasks perceived as dirty, such as contact with body uids or with patients or body parts perceived as unclean (I think that when youve touched a patient who was a bit sticky, you want to get rid of it [comments by a physician]). All participants mentioned that they were most likely to perform hand hygiene when they felt that their hands were dirty, before they ate, and at the end of their shift. Disadvantages of hand hygiene compliance. The disadvantages participants specied as being associated with performance of hand hygiene, mainly dryness and soreness of hands after performance of hand hygiene, were similar among all 3 groups. Furthermore, physicians and nurses mentioned the amount of time necessary for adequate hand hygiene. Subjective Norms Social control. All participants mentioned a lack of social control with regard to compliance with hand hygiene guidelines, and all groups reported difculties in addressing others about their hand hygiene behavior (I think lots of people see it [ie, the lack of hand hygiene], but dont say anything [comments by a medical student]). Role models. Nurses and particularly medical students mentioned the presence of negative role modelsthat is, experienced nurses or physicians who were noncompliant with hand hygiene guidelinesas reasons for their own noncompliance. Medical students explicitly mentioned that they are unable to comply if the rest of the group fails to comply. They would otherwise fall behind during rounds, and they reported feeling strongly inuenced by negative role models to abstain from compliance with hand hygiene guidelines (To a great extent, I copy the behavior of the physicians and staff members [comments by a medical student]). Furthermore, medical students and nurses reported that they adjust their behavior to match the behavior that they witness in practice (If you arrive here and no one washes their handsyes, I think you copy that behavior. You think thats what they do so that must be right [comments by a nurse]). Physicians also reported the need for positive role models. Norms. In all groups, a discussion arose about the culture in the hospital, in which it is accepted that physicians, particularly senior staff, deviate from the set of rules and guidelines, and its importance as reason for noncompliance (Those at the bottom of the ladder make sure that everything is done correctly, and then a staff member [ie, a physician] walks in without washing his hands and everything is wasted

[comments by a physician]). All participants agreed that creating a stronger social norm and establishing more explicit social control would be important for improving hand hygiene compliance. Perceived Behavioral Control Barriers to hand hygiene compliance mentioned by participants were the occurrence of emergent situations, the lack of availability of and easy access to hand hygiene materials, the lack of time, and forgetfulness. Furthermore, improving the availability and accessibility of materials and nonirritating hand alcohol rubs were mentioned as important facilitators to improve compliance. Physicians reported that the scarcity of evidence-based research supporting the role of hand hygiene in the prevention of hospital-acquired infections is a barrier for compliance (There should be data [about the effectiveness of hand hygiene], real data, presentations, and reports so that people can read about it [comments by a physician]).

discussion

With the help of a qualitative study design, we analyzed the behavioral determinants of hand hygiene compliance among different hospital healthcare workers, including physicians, nurses, and medical students. The hand hygiene behavior of healthcare workers appears to be motivated by self-protection and a desire to clean oneself after a task that is perceived to be dirty. Nurses and medical students expressed the importance of hand hygiene for preventing cross-infection among patients and themselves, whereas physicians expressed the importance of hand hygiene but also perceived a lack of evidence for the importance of hand hygiene in preventing crossinfection. Personal beliefs about the efcacy of hand hygiene and the examples set and norms established by senior staff in a hospital are of major importance for hand hygiene compliance. Medical students tend to copy the hand hygiene behavior of their superiors, leading to noncompliance when they observe noncompliance by others. Physicians mentioned that their noncompliance was associated with a perceived lack of evidence that hand hygiene is effective in the prevention of hospital-acquired infection, which could be an explanation for the inverse correlation found between the level of education and the rate of handwashing compliance.22 Behavioral research into hand hygiene compliance is highly needed because it is essential for developing successful multifaceted interventions.8,11 A qualitative study of hand hygiene was performed by Whitby et al.,12 although it focused more on hand washing in the community setting and included a group of participants (children, mothers, and nurses) that differed from those in our study (physicians, nurses, and medical students). Despite the differences, one striking similarity can be found in the data about nurses attitudes towards hand washing at work. The nurses in the study by Whitby

418

infection control and hospital epidemiology

may 2009, vol. 30, no. 5

and colleagues reported that their level of compliance is inuenced by their own assessment of the degree of dirtiness or the lack of cleanliness of a patient, which was also found in our study. This assessment results in performance of hand hygiene mainly after direct contact with the patient. It also indicates of a lack of knowledge about the presence of pathogens in the vicinity of the patient and on such items as door handles and telephones. Increased knowledge about such pathogens, combined with the desire to feel clean, could lead to better hand hygiene compliance after contact with these inanimate objects. That hand hygiene is mainly performed after patient contact is supported not only by the results from the study by Whitby et al.,12 but also by numerous studies measuring hand hygiene performance in practice.16,23-27 In general, these studies nd much higher rates of hand hygiene after patient contact than before patient contact. This provides another indication that the motivation for performing hand hygiene is perhaps inuenced more by the inherent desire to clean oneself when feeling dirty than by an interest in protecting the patient, as previously suggested by Whitby et al.12 In the same study, Whitby and colleagues further found that elective in-hospital handwashing behavior was significantly inuenced by the nurses beliefs about the benets of the activity, by peer pressure from senior physicians and administrators, and by role modeling. Pittet et al.28 performed a quantitative study among physicians and found that observed physician adherence was mainly predicted by variables related to the environmental context, to social pressure and the perceived risk of cross-transmission, and to a positive individual attitude toward hand hygiene. The results presented in both studies conrm our results and underline the importance of social norms and culture for compliance with hand hygiene guidelines. Physicians mentioned a need for more social control to improve their hand hygiene behavior, although it remains unclear who should provide this control. Most physicians do not feel inclined to comment on the hand hygiene behavior of their colleagues, and some feel that nurses should perform this task. However, only a few nurses (mostly older, more-experienced nurses) mentioned ever having commented on the hand hygiene behavior of physicians. Furthermore, medical students appear to copy the hand hygiene behavior of the physicians they see at work, often resulting in poor hand hygiene habits that will, in turn, be copied by future students. Positive role models are essential in breaking the cycle.2 However, most physicians do not see themselves as role models, and many appear to be uninclined to change their behavior. Authorities responsible for medical training of physicians in all career phases should be involved in promoting better hand hygiene compliance, because doing so may improve compliance across the hierarchy of healthcare professionals. Because not all physicians are convinced that sound rationale supports the effectiveness of hand hygiene, an independent synthesis of the available evidence from controlled quasi-

experimental studies on the role of hand hygiene in the prevention of cross-infection should also be conducted. When interpreting the aforementioned results, a number of limitations have to be taken into account. Different groups of healthcare workers participated in this study. However, the number of participating physicians was relatively small because of the impracticality of focus group interviews for this profession. This, in effect, generated 2 types of qualitative data, one from group discussions and another from individual interviews. On the other hand, the quality of the data is strengthened by the participation of different types of healthcare workers and by the inclusion of healthcare workers from different institutions. This, in combination with the considerable degree of consistency in the answers given, enhances the generalizability of the results. It is furthermore important to consider that the value of the ndings presented here lies in their qualitative nature; that is, they are useful in the preliminary identication of possible factors inuencing hand hygiene compliance. These factors can then be investigated further in quantitative and experimental research.

conclusions

The results of this qualitative study indicate that beliefs about the importance of self-protection are the main reasons for performing hand hygiene. Lack of positive role models among and social norms established by senior physicians may hinder compliance. The results from this study should inform methods for stimulating hand hygiene compliance in healthcare settings. If hand hygiene is indeed mainly inuenced by the desire to clean oneself and by the behavior of other healthcare professionals, then workshops and courses that focus on patient protection may have little effect. The best methods for improving hand hygiene compliance may involve encouraging senior healthcare workers to be compliant and creating a supportive environment with readily available and easily accessible hand hygiene facilities.

acknowledgments

We thank Meeke Hoedjes and Tinneke Beierens, for their help during the focus groups interviews, and all healthcare workers who participated in this study. Financial support. This project was funded by ZonMW (grant 24300036). The funding source had no involvement in the study and the authors work is independent. Potential conicts of interest. All authors report no conicts of interest relevant to this article. Address reprint requests to V. Erasmus, MSc, Department of Public Health, University Medical Center Rotterdam, P.O. Box 2040, 3000 CA, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (v.erasmus@erasmusmc.nl).

references

1. Donaldson L. Dirty handsthe human cost. London, United Kingdom: UK Department of Public Health; 2006.

poor hand hygiene during hospitalization

419

2. Group HL. Hand washing. BMJ 1999; 318:686. 3. Teare L, Cookson B, Stone S. Hand hygiene. BMJ 2001; 323:411412. 4. Stone S, Teare L, Cookson B. Guiding hands of our teachers. Handhygiene Liaison Group. Lancet 2001; 357:479480. 5. Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Sax H, et al. Evidence-based model for hand transmission during patient care and the role of improved practices. Lancet Infect Dis 2006; 6:641652. 6. World Alliance for Patient Safety. Global patient safety challenge 20052006: clean care is safer care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. 7. Day M. Chief medical ofcer names hand hygiene and organ donation as public health priorities. BMJ 2007; 335:113. 8. Jumaa PA. Hand hygiene: simple and complex. Int J Infect Dis 2005; 9: 314. 9. Naikoba S, Hayward A. The effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing handwashing in healthcare workersa systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2001; 47:173180. 10. Larson EL, Bryan JL, Adler LM, Blane C. A multifaceted approach to changing handwashing behavior. Am J Infect Control 1997; 25:310. 11. Pittet D, Mourouga P, Perneger TV. Compliance with handwashing in a teaching hospital. Infection Control Program. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130:126130. 12. Whitby M, McLaws ML, Ross MW. Why healthcare workers dont wash their hands: a behavioral explanation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2006; 27:484492. 13. Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Sage; 1997. 14. Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. London, United Kingdom: Sage; 2002. 15. Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Planning health promotion programs; an intervention mapping approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006. 16. OBoyle CA, Henly SJ, Larson E. Understanding adherence to hand hygiene recommendations: the theory of planned behavior. Am J Infect Control 2001; 29:352360.

17. Creedon SA. Healthcare workers hand decontamination practices: compliance with recommended guidelines. J Adv Nurs 2005; 51:208216. 18. Lipsett PA, Swoboda SM. Handwashing compliance depends on professional status. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2001; 2:241245. 19. Pittet D, Hugonnet S, Harbath S. Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene (published correction appears in Lancet 2000; 356:2196). Lancet 2000; 356:13071312. 20. Feather A, Stone SP, Wessier A, Boursicot KA, Pratt C. Now please wash your hands: the handwashing behaviour of nal MBBS candidates. J Hosp Infect 2000; 45:6264. 21. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec Processes 1991; 50:179211. 22. Duggan JM, Hensley S, Khuder S, Papadimos TJ, Jacobs L. Inverse correlation between level of professional education and rate of handwashing compliance in a teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008; 29: 534538. 23. Aragon D, Sole ML, Brown S. Outcomes of an infection prevention project focusing on hand hygiene and isolation practices. AACN Clin Issues 2005; 16:121132. 24. Golan Y, Doron S, Grifth J, et al. The impact of gown-use requirement on hand hygiene compliance. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42:370376. 25. Lankford MG, Zembower TR, Trick WE, Hacek DM, Noskin GA, Peterson LR. Inuence of role models and hospital design on hand hygiene of healthcare workers. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:217223. 26. MacDonald A, Dinah F, MacKenzie D, Wilson A. Performance feedback of hand hygiene, using alcohol gel as the skin decontaminant, reduces the number of inpatients newly affected by MRSA and antibiotic costs. J Hosp Infect 2004; 56:5663. 27. OBoyle CA, Henly SJ, Duckett LJ. Nurses motivation to wash their hands: a standardized measurement approach. Appl Nurs Res 2001; 14: 136145. 28. Pittet D, Simon A, Hugonnet S, Pessoa-Silva CL, Sauvan V, Perneger TV. Hand hygiene among physicians: performance, beliefs, and perceptions. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:18.

You might also like

- Hand Hygiene StoryboardDocument9 pagesHand Hygiene StoryboardVera IndrawatiNo ratings yet

- Hospitalist Program Toolkit: A Comprehensive Guide to Implementation of Successful Hospitalist ProgramsFrom EverandHospitalist Program Toolkit: A Comprehensive Guide to Implementation of Successful Hospitalist ProgramsNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding Resources Poster GuideDocument3 pagesBreastfeeding Resources Poster GuideDhea Rizky Amelia SatoNo ratings yet

- Rotation: Medical Intensive Care Unit (South Campus) For Interns and ResidentsDocument6 pagesRotation: Medical Intensive Care Unit (South Campus) For Interns and ResidentsHashimIdreesNo ratings yet

- Critical ThinkingDocument7 pagesCritical ThinkingAru VermaNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Hygiene Practices of Food Handlers in Bakori CommunityDocument56 pagesAssessing The Hygiene Practices of Food Handlers in Bakori CommunityUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument12 pagesThesisJanna DatahanNo ratings yet

- Panduan-Pasien-RSDocument12 pagesPanduan-Pasien-RSEko Wahyu AgustinNo ratings yet

- QTB Study Pack Final FinalDocument126 pagesQTB Study Pack Final FinalQaiser IqbalNo ratings yet

- Using Effective Hand Hygiene Practice To Prevent and Control InfectionDocument6 pagesUsing Effective Hand Hygiene Practice To Prevent and Control Infectionfarida nur ainiNo ratings yet

- Data Gathering ProceduresDocument2 pagesData Gathering ProceduresYessaminNo ratings yet

- Bekele ChakaDocument74 pagesBekele ChakaDoods QuemadaNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2Document3 pagesCase Study 2JoPaul Prado100% (2)

- Marketing Mix - The 4 P's of Marketing ExplainedDocument6 pagesMarketing Mix - The 4 P's of Marketing ExplainedDeepak Kalonia JangraNo ratings yet

- Hand Hygiene Compliance ReviewDocument126 pagesHand Hygiene Compliance ReviewHosam GomaaNo ratings yet

- Mod2 - Ch3 - Health IndicatorsDocument13 pagesMod2 - Ch3 - Health IndicatorsSara Sunabara100% (1)

- Administrative Order No. 2005-0032Document14 pagesAdministrative Order No. 2005-0032Cherrylou BudayNo ratings yet

- Ahrq 2004 PDFDocument74 pagesAhrq 2004 PDFDelly TunggalNo ratings yet

- 4TH PT1 MethodologyDocument7 pages4TH PT1 MethodologyKirito - kunNo ratings yet

- Handout Core CompetenciesDocument4 pagesHandout Core CompetenciesAi CaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Staffing StrategiesDocument63 pagesNursing Staffing StrategiesHannah DuyagNo ratings yet

- Patient Safety Indicator PDFDocument149 pagesPatient Safety Indicator PDFDang RajoNo ratings yet

- Seminar PresentationDocument31 pagesSeminar Presentationapi-520940649No ratings yet

- PDSA Directions and Examples: IHI (Institute For Healthcare Improvement) Web SiteDocument8 pagesPDSA Directions and Examples: IHI (Institute For Healthcare Improvement) Web Siteanass sbniNo ratings yet

- The Good Ones Chapter 3Document6 pagesThe Good Ones Chapter 3jasmin grace tanNo ratings yet

- Designing Health Promotion ProgramDocument10 pagesDesigning Health Promotion ProgramThe HoopersNo ratings yet

- NR Thesis1Document40 pagesNR Thesis1ceicai100% (1)

- MODULE 3 STUDENT National Patient Safety Goals 2013Document15 pagesMODULE 3 STUDENT National Patient Safety Goals 2013Dewi Ratna Sari100% (1)

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaDocument10 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Standard Operating Proceduresgov1Document197 pagesStandard Operating Proceduresgov1Adam ShawNo ratings yet

- ISOBAR Clinical HandoverDocument3 pagesISOBAR Clinical HandoverSamer FarhanNo ratings yet

- Patient Safety: What Should We Be Trying To Communicate?Document32 pagesPatient Safety: What Should We Be Trying To Communicate?cicaklomenNo ratings yet

- JCIA Update Documentation StandardsDocument26 pagesJCIA Update Documentation StandardsBayuaji SismantoNo ratings yet

- Perceived Safety Culture of Healthcare Providers in Hospitals in The PhilippinesDocument14 pagesPerceived Safety Culture of Healthcare Providers in Hospitals in The PhilippinesRhod Bernaldez EstaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 MelDocument6 pagesChapter 3 MelJefferson MoralesNo ratings yet

- Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument5 pagesAdvantages and DisadvantagesKyla RodriguezaNo ratings yet

- OlistDocument19 pagesOlistAnkush PawarNo ratings yet

- Republic Act DOHDocument45 pagesRepublic Act DOHMARIA AURORA COMMUNITY HOSPITALNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument24 pagesThesisapi-297856632No ratings yet

- Camiguin Hospital Safety PlansDocument131 pagesCamiguin Hospital Safety PlansJay Raymund Aranas BagasNo ratings yet

- Pico HandwashingDocument21 pagesPico HandwashingAnonymous gkInz9No ratings yet

- PfeDocument2 pagesPfeCaryl Lou Casamayor100% (3)

- Seminar JCI - 9 Feb 2012Document16 pagesSeminar JCI - 9 Feb 2012Mahardika PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Emergency Nurses Association (ENA)Document5 pagesEmergency Nurses Association (ENA)Ngu W PhooNo ratings yet

- g7 Research Proposal FinalDocument36 pagesg7 Research Proposal FinalChristian Leo Venzon MoringNo ratings yet

- Drug Abuse Among The Students PDFDocument7 pagesDrug Abuse Among The Students PDFTed MosbyNo ratings yet

- COMPETENCIES - Bag TechniqueDocument3 pagesCOMPETENCIES - Bag TechniquejokazelNo ratings yet

- Hospital Quality Reporting SystemDocument5 pagesHospital Quality Reporting SystemumeshbhartiNo ratings yet

- Problems Affecting Work Performance of Healthcare Practitioners in Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi ArabiaDocument11 pagesProblems Affecting Work Performance of Healthcare Practitioners in Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi ArabiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Thesis Pin Aka Final Ye HeyDocument50 pagesThesis Pin Aka Final Ye HeyKaith Budomo LocadingNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Versus Multidisciplinary Care Teams - Do We Understand The DifferenceDocument2 pagesInterdisciplinary Versus Multidisciplinary Care Teams - Do We Understand The DifferenceSinisa RudanNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal Cross-Sectional Studies Aug 2011Document3 pagesCritical Appraisal Cross-Sectional Studies Aug 2011dwilico100% (1)

- Patient SatisfactionDocument18 pagesPatient Satisfactionali adnanNo ratings yet

- HBPM ProtocolDocument8 pagesHBPM ProtocolGutemhcNo ratings yet

- IPSG PresentationDocument38 pagesIPSG Presentationmuhammed shamaa100% (1)

- The Value of Healthcare AdministrationDocument3 pagesThe Value of Healthcare AdministrationKrizzella ShainaNo ratings yet

- Skill For Health PromotionDocument244 pagesSkill For Health PromotionElly MartinsNo ratings yet

- Staffing-Term PaperDocument9 pagesStaffing-Term PaperRodel CamposoNo ratings yet

- Improving Healthcare Through Advocacy: A Guide for the Health and Helping ProfessionsFrom EverandImproving Healthcare Through Advocacy: A Guide for the Health and Helping ProfessionsNo ratings yet

- GrandTheorists PaperDocument4 pagesGrandTheorists PaperMarsha WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Global Health Nursing Roles in the 21st CenturyDocument46 pagesGlobal Health Nursing Roles in the 21st CenturyJosefa CapuyanNo ratings yet

- Theorycritiqueof Florence Nightingale Environmental Theoryusing FawcettsmodelDocument7 pagesTheorycritiqueof Florence Nightingale Environmental Theoryusing FawcettsmodelMarsha WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Florence Nightingale Content OutlineDocument8 pagesFlorence Nightingale Content OutlineMarsha Williams100% (1)

- Orem PresentationDocument26 pagesOrem PresentationMarsha WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Algorithm 1: Initial Evaluation and Management: Symptoms of Possible ACSDocument6 pagesAlgorithm 1: Initial Evaluation and Management: Symptoms of Possible ACSNenyNo ratings yet

- Employee contact listDocument16 pagesEmployee contact listabreddy2003No ratings yet

- Faye Glenn AbdellahDocument3 pagesFaye Glenn AbdellahZia BrionesNo ratings yet

- Makalah Plendis Blok 24Document23 pagesMakalah Plendis Blok 24Alvian RamadyaNo ratings yet

- Manual Triage BagusDocument79 pagesManual Triage BagusHengkyNo ratings yet

- Laura Guthridge CV Teaching PortfolioDocument9 pagesLaura Guthridge CV Teaching Portfolioapi-252595603No ratings yet

- 3a Competency Assessment - Patient Controlled AnalgesiaDocument2 pages3a Competency Assessment - Patient Controlled AnalgesiaQuijano GpokskieNo ratings yet

- Summary The Checklist ManifestoDocument7 pagesSummary The Checklist ManifestoRajeev BahugunaNo ratings yet

- S M C L: Aint Ichael'S Ollege of AgunaDocument12 pagesS M C L: Aint Ichael'S Ollege of AgunaChriza Joy BartolomeNo ratings yet

- MH Space RequirementsDocument55 pagesMH Space RequirementsV- irusNo ratings yet

- March 11-25Document6 pagesMarch 11-25eldon sarmientoNo ratings yet

- Hidden HeartDocument171 pagesHidden HeartElinor Anne Rivera100% (3)

- HR & Training Study at AMRI HospitalDocument123 pagesHR & Training Study at AMRI HospitalSayantan MandalNo ratings yet

- Commercial Dispatch Eedition 6-6-19Document12 pagesCommercial Dispatch Eedition 6-6-19The DispatchNo ratings yet

- Projections No 1Document286 pagesProjections No 1frame-paradiso100% (1)

- University Medical Reimbursement FormDocument4 pagesUniversity Medical Reimbursement Formmujunaidphd5581No ratings yet

- An Overview of The Surgical Correction of Dentofacial DeformityDocument9 pagesAn Overview of The Surgical Correction of Dentofacial DeformityAhmad AssariNo ratings yet

- Relative pronoun and participle clause quizDocument4 pagesRelative pronoun and participle clause quizΓΙΑΝΝΗΣ ΚΟΝΔΥΛΗΣ100% (1)

- Health RecordsDocument356 pagesHealth RecordsMoosa MohamedNo ratings yet

- Manila Doctors Hospital CCU Conference on Pulmonary EmbolismDocument5 pagesManila Doctors Hospital CCU Conference on Pulmonary EmbolismFayeListanco100% (1)

- The Presence of Spirits in MadnessDocument17 pagesThe Presence of Spirits in MadnessRob Zel100% (4)

- Varanasi City ProfileDocument4 pagesVaranasi City ProfileJohn Nunez100% (1)

- Role of Hospitals in Health Care SystemDocument10 pagesRole of Hospitals in Health Care SystemManojNo ratings yet

- Review: How Much Can You Remember? Team NameDocument2 pagesReview: How Much Can You Remember? Team NameVirgínia ToledoNo ratings yet

- Narrative ReportDocument2 pagesNarrative ReportJamal Tango Alawiya100% (1)

- Urgent Care Clinic Improves Patient Flow by 30 MinutesDocument2 pagesUrgent Care Clinic Improves Patient Flow by 30 MinuteselonaNo ratings yet

- Latonya Ruiz ResumeDocument3 pagesLatonya Ruiz Resumeapi-284274038No ratings yet

- Data Collection Form-PainAIRCycleDocument1 pageData Collection Form-PainAIRCycleErwin Dela GanaNo ratings yet

- The miracle of the human brain (less than 40 chars: 35 charsDocument6 pagesThe miracle of the human brain (less than 40 chars: 35 charsAbhijeet SavantNo ratings yet

- 1 Guidelines For Anesthetic Management in Clinical PracticeDocument54 pages1 Guidelines For Anesthetic Management in Clinical PracticeAMVAC RomaniaNo ratings yet