Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Credit Cases - Chap. 1-2

Uploaded by

Trish VerzosaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Credit Cases - Chap. 1-2

Uploaded by

Trish VerzosaCopyright:

Available Formats

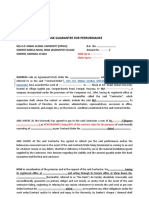

Credit Transactions

COMMODATUM EN BANC [G.R. No. L-17474. October 25, 1962.] REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee, vs. JOSE V. BAGTAS, defendant. FELICIDAD M. BAGTAS, Administratrix of the Intestate Estate left by the late Jose V. Bagtas, petitioner-appellant. DECISION PADILLA, J p: The Court of Appeals certified this case to this Court because only questions of law are raised. On 8 May 1948 Jose V. Bagtas borrowed from the Republic of the Philippines through the Bureau of Animal Industry three bulls: a Red Sindhi with a book value of P1,176.46, a Bhagnari, of P1,320.56 and a Sahiniwal, of P744.46, for a period of one year from 8 May 1948 to 7 May 1949 for breeding purposes subject to a government charge of breeding fee of 10% of the book value of the bulls. Upon the expiration on 7 May 1949 of the contract, the borrower asked for a renewal for another period of one year. However, the Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources approved a renewal thereof of only one bull for another year from 8 May 1949 to 7 May 1950 and requested the return of the other two. On 25 March 1950 Jose V. Bagtas wrote to the Director of Animal Industry that he would pay the value of the three bulls. On 17 October 1950 he reiterated his desire to buy them at a value with a deduction of yearly depreciation to be approved by the Auditor General. On 19 October 1950 the Director of Animal Industry advised him that the book value of the three bulls could not be reduced and that they either be returned or their book value paid not later than 31 October 1950. Jose V. Bagtas failed to pay the book value of the three bulls or to return them. So, on 20 December 1950 in the Court of First Instance of Manila the Republic of the Philippines commenced an action against him praying that he be ordered to return the three bulls loaned to him or to pay their book value in the total sum of P3,241.45 and the unpaid breeding fee in the sum of P499.62, both with interests, and costs; and that other just and equitable relief be granted it (civil No. 12818). On 5 July 1951 Jose V. Bagtas, through counsel Navarro, Rosete and Manalo, answered that because of the bad peace and order situation in Cagayan Valley, particularly in the barrio of Baggao, and of the pending appeal he had taken to the Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources and the President of the Philippines from the refusal by the Director of Animal Industry to deduct from the book value of the bulls corresponding yearly depreciation of 8% from the date of acquisition, to which depreciation the Auditor General did not object, he could not return the animals nor pay their value and prayed for the dismissal of the complaint. After hearing, on 30 July 1956 the trial court rendered judgment

Credit Transactions

. . . sentencing the latter (defendant) to pay the sum of P3,625.09 the total value of the three bulls plus the breeding fees in the amount of P626.17 with interest on both sums of (at) the legal rate from the filing of this complaint and costs. On 9 October 1958 the plaintiff moved ex parte for a writ of execution which the court granted on 18 October and issued on 11 November 1958. On 2 December 1958 it granted an ex-parte motion filed by the plaintiff on 28 November 1958 for the appointment of a special sheriff to serve the writ outside Manila. Of this order appointing a special sheriff, on 6 December 1958 Felicidad M. Bagtas, the surviving spouse of the defendant Jose V. Bagtas who died on 23 October 1951 and as administratrix of his estate, was notified. On 7 January 1959 she filed a motion alleging that on 26 June 1952 the two bulls, Sindhi and Bhagnari, were returned to the Bureau of Animal Industry and that sometime in November 1953 the third bull, the Sahiniwal, died from gunshot wounds inflicted during a Huks raid on Hacienda Felicidad Intal, and praying that the writ of execution be quashed and that a writ of preliminary injunction be issued. On 31 January 1959 the plaintiff objected to her motion. On 6 February 1959 she filed a reply thereto. On the same day, 6 February, the Court denied her motion. Hence, this appeal certified by the Court of Appeals to this Court, as stated at the beginning of this opinion. It is true that on 26 June 1952 Jose M. Bagtas, Jr., son of the appellant by the late defendant, returned the Sindhi and Bhagnari bulls to Roman Remorin, Superintendent of the NVB Station, Bureau of Animal Industry, Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya, as evidenced by a memorandum receipt signed by the latter (Exhibit 2). That is why in its objection of 31 January 1959 to the appellant's motion to quash the writ of execution the appellee prays "that another writ of execution in the sum of P859.5.3 be issued against the estate of defendant deceased Jos V. Bagtas." She cannot be held liable for the two bulls which already had been returned to and received by the appellee. The appellant contends that the Sahiniwal bull was accidentally killed during a raid by the Huks in November 1953 upon the surrounding barrios of Hacienda Felicidad Intal, Baggao, Cagayan, where the animal was kept, and that as such death was due to force majeure she is relieved from the duty of the returning the bull or paying its value to the appellee. The contention is without merit. The loan by the appellee to the late defendant Jos V. Bagtas of the three bulls for breeding purposes for a period of one year from 8 May 1948 to 7 May 1949, later on renewed for another year as regards one bull, was subject to the payment by the borrower of breeding fee of 10% of the book value of the bulls. The appellant contends that the contract was commodatum and that, for that reason, as the appellee retained ownership or title to the bull it should suffer its loss due to force majeure A contract of commodatum is essentially gratuitous. 1 If the breeding fee be considered a compensation, then the contract would be a lease of the bull. Under article 1671 of the Civil Code the lessee would be subject to the responsibilities of a possessor in bad faith, because she had continued possession of the bull after the expiry of the contract. And even if the contract be commodatum, still the appellant is liable, because article 1942 of the Civil Code provides that a bailee in a contract of commodatum . . . is liable for loss of the thing, even if it should be through a fortuitous event:

Credit Transactions

(2)

If he keeps it longer than the period stipulated. . . .

(3) If the thing loaned has been delivered with appraisal of its value, unless there is a stipulation exempting the bailee from responsibility in case of a fortuitous event: The original period of the loan was from 8 May 1948 to 7 May 1949. The loan of one bull was renewed for another period of one year to end on 8 May 1950. But the appellant kept and used the bull until November 1953 when during a Huk raid it was killed by stray bullets. Furthermore, when lent and delivered to the deceased husband of the appellant the bulls had each an appraised book value, to wit: the Sindhi, at P1,176.46; the Bhagnari, at P1,320.56 and the Sahiniwal; at P744.46. It was not stipulated that in case of loss of the bull due to fortuitous event the late husband of the appellant would be exempt from liability. The appellant's contention that the demand or prayer by the appellee for the return of the bull or the payment of its value being a money claim should be presented or filed in the intestate proceedings of the defendant who died on 23 October 1951, is not altogether without merit. However, the claim that his civil personality having ceased to exist the trial court lost jurisdiction over the case against him, is untenable, because section 17 of Rule 3 of the Rules of Court provides that After a party dies and the claim is not thereby extinguished, the court shall order, upon proper notice, the legal representative of the deceased to appear and to be substituted for the deceased, within a period of thirty (30) days, or within such time as may be granted . . . . and after the defendant's death on 23 October 1951 his counsel failed to comply with section 16 of Rule 3 which provides that Whenever a party to a pending case dies . . . it shall be the duty of his attorney to inform the court promptly of such death . . . and to give the name and residence of the executor or administrator, guardian, or other legal representative of the deceased . . . The notice by the probate court and its publication in the Voz de Manila that Felicidad M. Bagtas had been issued letters of administration of the estate of the late Jos V. Bagtas and that "all persons having claims for money against the deceased Jos V. Bagtas, arising from contract, express or implied, whether the same be due, not due, or contingent, for funeral expenses and expenses of the last sickness of the said decedent, and judgment for money against him, to file said claims with the Clerk of this Court at the City Hall Bldg., Highway 54, Quezon City, within six (6) months from the date of the first publication of this order, serving a copy thereof upon the aforementioned Felicidad M. Bagtas, the appointed administratrix of the estate of the said deceased," is not a notice to the court and the appellee who were to be notified of the defendant's death in accordance with the abovequoted rule, and there was no reason for such failure to notify, because the attorney who appeared for the defendant was the same who represented the administratrix in the special proceedings instituted for the administration and settlement of his estate. The appellee or its attorney or representative could not be expected to know of the death of the defendant or of the administration proceedings of

Credit Transactions

his estate instituted in another court, if the attorney for the deceased defendant did not notify the plaintiff or its attorney of such death as required by the rule. As the appellant already had returned the two bulls to the appellee, the estate of the late defendant is only liable for the sum of P859.63, the value of the bull which has not been returned to the appellee, because it was killed while in the custody of the administratrix of his estate. This is the amount prayed for by the appellee in its objection on 31 January 1959 to the motion filed on 7 January 1959 by the appellant for the quashing of the writ of execution. Special proceedings for the administration and settlement of the estate of the deceased Jos V. Bagtas having been instituted in the Court of First Instance of Rizal (Q-200), the money judgment rendered in favor of the appellee cannot be enforced by means of a writ of execution but must be presented to the probate court for payment by the appellant, the administratrix appointed by the court. ACCORDINGLY, the writ of execution appealed from is set aside, without pronouncement as to costs.

G.R. No. L-46240

November 3, 1939

MARGARITA QUINTOS and ANGEL A. ANSALDO, plaintiffs-appellants, vs. BECK, defendant-appellee. IMPERIAL, J.: The plaintiff brought this action to compel the defendant to return her certain furniture which she lent him for his use. She appealed from the judgment of the Court of First Instance of Manila which ordered that the defendant return to her the three has heaters and the four electric lamps found in the possession of the Sheriff of said city, that she call for the other furniture from the said sheriff of Manila at her own expense, and that the fees which the Sheriff may charge for the deposit of the furniture be paid pro rata by both parties, without pronouncement as to the costs. The defendant was a tenant of the plaintiff and as such occupied the latter's house on M. H. del Pilar street, No. 1175. On January 14, 1936, upon the novation of the contract of lease between the plaintiff and the defendant, the former gratuitously granted to the latter the use of the furniture described in the third paragraph of the stipulation of facts, subject to the condition that the defendant would return them to the plaintiff upon the latter's demand. The plaintiff sold the property to Maria Lopez and Rosario Lopez and on September 14, 1936, these three notified the defendant of the conveyance, giving him sixty days to vacate the premises under one of the clauses of the contract of lease. There after the plaintiff required the defendant to return all the furniture transferred to him for them in the house where they were found. On November 5, 1936, the defendant, through another person, wrote to the plaintiff reiterating that she may call for the furniture in the ground floor of the house. On the 7th of the same month, the defendant wrote another letter to the plaintiff informing her that he could not give up

Credit Transactions

the three gas heaters and the four electric lamps because he would use them until the 15th of the same month when the lease in due to expire. The plaintiff refused to get the furniture in view of the fact that the defendant had declined to make delivery of all of them. On November 15th, before vacating the house, the defendant deposited with the Sheriff all the furniture belonging to the plaintiff and they are now on deposit in the warehouse situated at No. 1521, Rizal Avenue, in the custody of the said sheriff. In their seven assigned errors the plaintiffs contend that the trial court incorrectly applied the law: in holding that they violated the contract by not calling for all the furniture on November 5, 1936, when the defendant placed them at their disposal; in not ordering the defendant to pay them the value of the furniture in case they are not delivered; in holding that they should get all the furniture from the Sheriff at their expenses; in ordering them to pay-half of the expenses claimed by the Sheriff for the deposit of the furniture; in ruling that both parties should pay their respective legal expenses or the costs; and in denying pay their respective legal expenses or the costs; and in denying the motions for reconsideration and new trial. To dispose of the case, it is only necessary to decide whether the defendant complied with his obligation to return the furniture upon the plaintiff's demand; whether the latter is bound to bear the deposit fees thereof, and whether she is entitled to the costs of litigation.lawphi1.net The contract entered into between the parties is one of commadatum, because under it the plaintiff gratuitously granted the use of the furniture to the defendant, reserving for herself the ownership thereof; by this contract the defendant bound himself to return the furniture to the plaintiff, upon the latters demand (clause 7 of the contract, Exhibit A; articles 1740, paragraph 1, and 1741 of the Civil Code). The obligation voluntarily assumed by the defendant to return the furniture upon the plaintiff's demand, means that he should return all of them to the plaintiff at the latter's residence or house. The defendant did not comply with this obligation when he merely placed them at the disposal of the plaintiff, retaining for his benefit the three gas heaters and the four eletric lamps. The provisions of article 1169 of the Civil Code cited by counsel for the parties are not squarely applicable. The trial court, therefore, erred when it came to the legal conclusion that the plaintiff failed to comply with her obligation to get the furniture when they were offered to her. As the defendant had voluntarily undertaken to return all the furniture to the plaintiff, upon the latter's demand, the Court could not legally compel her to bear the expenses occasioned by the deposit of the furniture at the defendant's behest. The latter, as bailee, was not entitled to place the furniture on deposit; nor was the plaintiff under a duty to accept the offer to return the furniture, because the defendant wanted to retain the three gas heaters and the four electric lamps. As to the value of the furniture, we do not believe that the plaintiff is entitled to the payment thereof by the defendant in case of his inability to return some of the furniture because under paragraph 6 of the stipulation of facts, the defendant has neither agreed to nor admitted the correctness of the said value. Should the defendant fail to deliver some of the furniture, the value thereof should be latter determined by the trial Court through evidence which the parties may desire to present. The costs in both instances should be borne by the defendant because the plaintiff is the prevailing party (section 487 of the Code of Civil Procedure). The defendant was the one who breached the contract ofcommodatum, and without any reason he refused to return and deliver all the furniture upon the plaintiff's demand. In these circumstances, it is just and equitable that

Credit Transactions

he pay the legal expenses and other judicial costs which the plaintiff would not have otherwise defrayed. The appealed judgment is modified and the defendant is ordered to return and deliver to the plaintiff, in the residence to return and deliver to the plaintiff, in the residence or house of the latter, all the furniture described in paragraph 3 of the stipulation of facts Exhibit A. The expenses which may be occasioned by the delivery to and deposit of the furniture with the Sheriff shall be for the account of the defendant. the defendant shall pay the costs in both instances. So ordered. Avancea, C.J., Villa-Real, Laurel, Concepcion and Moran, JJ., concur.

G.R. No. 26085

August 12, 1927

SEVERINO TOLENTINO and POTENCIANA MANIO, plaintiffs-appellants, vs. BENITO GONZALEZ SY CHIAM, defendants-appellee. Araneta and Zaragoza for appellants. Eusebio Orense for appelle. JOHNSON, J.: PRINCIPAL QUESTIONS PRESENTED BY THE APPEAL The principal questions presented by this appeal are: (a) Is the contract in question a pacto de retro or a mortgage? (b) Under a pacto de retro, when the vendor becomes a tenant of the purchaser and agrees to pay a certain amount per month as rent, may such rent render such a contract usurious when the amount paid as rent, computed upon the purchase price, amounts to a higher rate of interest upon said amount than that allowed by law? (c) May the contract in the present case may be modified by parol evidence? ANTECEDENT FACTS Sometime prior to the 28th day of November, 1922, the appellants purchased of the Luzon Rice Mills, Inc., a piece or parcel of land with the camarin located thereon, situated in the municipality of Tarlac of the Province of Tarlac for the price of P25,000, promising to pay therefor in three installments. The first installment of P2,000 was due on or before the 2d day of May, 1921; the second installment of P8,000 was due on or before 31st day of May, 1921; the balance of P15,000 at 12 per cent interest was due and payable on or about the 30th day of November, 1922. One of the conditions of that contract of purchase was that on failure of the purchaser (plaintiffs and appellants) to pay the balance of said purchase price or any of the installments on the date agreed upon, the property bought would revert to the original owner.

Credit Transactions

The payments due on the 2d and 31st of May, 1921, amounting to P10,000 were paid so far as the record shows upon the due dates. The balance of P15,000 due on said contract of purchase was paid on or about the 1st day of December, 1922, in the manner which will be explained below. On the date when the balance of P15,000 with interest was paid, the vendor of said property had issued to the purchasers transfer certificate of title to said property, No. 528. Said transfer certificate of title (No. 528) was transfer certificate of title from No. 40, which shows that said land was originally registered in the name of the vendor on the 7th day of November, 1913. PRESENT FACTS On the 7th day of November, 1922 the representative of the vendor of the property in question wrote a letter to the appellant Potenciana Manio (Exhibit A, p. 50), notifying the latter that if the balance of said indebtedness was not paid, an action would be brought for the purpose of recovering the property, together with damages for non compliance with the condition of the contract of purchase. The pertinent parts of said letter read as follows: Sirvase notar que de no estar liquidada esta cuenta el dia 30 del corriente, procederemos judicialmente contra Vd. para reclamar la devolucion del camarin y los daos y perjuicios ocasionados a la compaia por su incumplimiento al contrato. Somos de Vd. atentos y S. S. SMITH, BELL & CO., LTD. By (Sgd.) F. I. HIGHAM Treasurer. General Managers LUZON RICE MILLS INC. According to Exhibits B and D, which represent the account rendered by the vendor, there was due and payable upon said contract of purchase on the 30th day of November, 1922, the sum P16,965.09. Upon receiving the letter of the vendor of said property of November 7, 1922, the purchasers, the appellants herein, realizing that they would be unable to pay the balance due, began to make an effort to borrow money with which to pay the balance due, began to make an effort to borrow money with which to pay the balance of their indebtedness on the purchase price of the property involved. Finally an application was made to the defendant for a loan for the purpose of satisfying their indebtedness to the vendor of said property. After some negotiations the defendants agreed to loan the plaintiffs to loan the plaintiffs the sum of P17,500 upon condition that the plaintiffs execute and deliver to him a pacto de retro of said property. In accordance with that agreement the defendant paid to the plaintiffs by means of a check the sum of P16,965.09. The defendant, in addition to said amount paid by check, delivered to the plaintiffs the sum of P354.91 together with the sum of P180 which the plaintiffs paid to the attorneys for drafting said contract of pacto de retro, making a total paid by the defendant to the plaintiffs and for the plaintiffs of P17,500 upon the execution and delivery of said contract.

Credit Transactions

Said contracts was dated the 28th day of November, 1922, and is in the words and figures following: Sepan todos por la presente: Que nosotros, los conyuges Severino Tolentino y Potenciana Manio, ambos mayores de edad, residentes en el Municipio de Calumpit, Provincia de Bulacan, propietarios y transeuntes en esta Ciudad de Manila, de una parte, y de otra, Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam, mayor de edad, casado con Maria Santiago, comerciante y vecinos de esta Ciudad de Manila. MANIFESTAMOS Y HACEMOS CONSTAR: Primero. Que nosotros, Severino Tolentino y Potenciano Manio, por y en consideracion a la cantidad de diecisiete mil quinientos pesos (P17,500) moneda filipina, que en este acto hemos recibido a nuestra entera satisfaccion de Don Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam, cedemos, vendemos y traspasamos a favor de dicho Don Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam, sus herederos y causahabientes, una finca que, segun el Certificado de Transferencia de Titulo No. 40 expedido por el Registrador de Titulos de la Provincia de Tarlac a favor de "Luzon Rice Mills Company Limited" que al incorporarse se donomino y se denomina "Luzon Rice Mills Inc.," y que esta corporacion nos ha transferido en venta absoluta, se describe como sigue: Un terreno (lote No. 1) con las mejoras existentes en el mismo, situado en el Municipio de Tarlac. Linda por el O. y N. con propiedad de Manuel Urquico; por el E. con propiedad de la Manila Railroad Co.; y por el S. con un camino. Partiendo de un punto marcado 1 en el plano, cuyo punto se halla al N. 41 gds. 17' E.859.42 m. del mojon de localizacion No. 2 de la Oficina de Terrenos en Tarlac; y desde dicho punto 1 N. 81 gds. 31' O., 77 m. al punto 2; desde este punto N. 4 gds. 22' E.; 54.70 m. al punto 3; desde este punto S. 86 gds. 17' E.; 69.25 m. al punto 4; desde este punto S. 2 gds. 42' E., 61.48 m. al punto de partida; midiendo una extension superficcial de cuatro mil doscientos diez y seis metros cuadrados (4,216) mas o menos. Todos los puntos nombrados se hallan marcados en el plano y sobre el terreno los puntos 1 y 2 estan determinados por mojones de P. L. S. de 20 x 20 x 70 centimetros y los puntos 3 y 4 por mojones del P. L. S. B. L.: la orientacion seguida es la verdadera, siendo la declinacion magnetica de 0 gds. 45' E. y la fecha de la medicion, 1. de febrero de 1913. Segundo. Que es condicion de esta venta la de que si en el plazo de cinco (5) aos contados desde el dia 1. de diciembre de 1922, devolvemos al expresado Don Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam el referido precio de diecisiete mil quinientos pesos (P17,500) queda obligado dicho Sr. Benito Gonzalez y Chiam a retrovendernos la finca arriba descrita; pero si transcurre dicho plazo de cinco aos sin ejercitar el derecho de retracto que nos hemos reservado, entonces quedara esta venta absoluta e irrevocable. Tercero. Que durante el expresado termino del retracto tendremos en arrendamiento la finca arriba descrita, sujeto a condiciones siguientes:

Credit Transactions

(a) El alquiler que nos obligamos a pagar por mensualidades vencidas a Don Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam y en su domicilio, era de trescientos setenta y cinco pesos (P375) moneda filipina, cada mes. (b) El amillaramiento de la finca arrendada sera por cuenta de dicho Don Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam, asi como tambien la prima del seguro contra incendios, si el conviniera al referido Sr. Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam asegurar dicha finca. (c) La falta de pago del alquiler aqui estipulado por dos meses consecutivos dara lugar a la terminacion de este arrendamieno y a la perdida del derecho de retracto que nos hemos reservado, como si naturalmente hubiera expirado el termino para ello, pudiendo en su virtud dicho Sr. Gonzalez Sy Chiam tomar posesion de la finca y desahuciarnos de la misma. Cuarto. Que yo, Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam, a mi vez otorgo que acepto esta escritura en los precisos terminos en que la dejan otorgada los conyuges Severino Tolentino y Potenciana Manio. En testimonio de todo lo cual, firmamos la presente de nuestra mano en Manila, por cuadruplicado en Manila, hoy a 28 de noviembre de 1922. (Fdo.) SEVERINO TOLENTINO (Fda.) POTENCIANA MANIO (Fdo.) BENITO GONZALEZ SY CHIAM Firmado en presencia de: (Fdos.) MOISES M. BUHAIN B. S. BANAAG An examination of said contract of sale with reference to the first question above, shows clearly that it is a pacto de retro and not a mortgage. There is no pretension on the part of the appellant that said contract, standing alone, is a mortgage. The pertinent language of the contract is: Segundo. Que es condicion de esta venta la de que si en el plazo de cinco (5) aos contados desde el dia 1. de diciembre de 1922, devolvemos al expresado Don Benito Gonzales Sy Chiam el referido precio de diecisiete mil quinientos pesos (P17,500) queda obligado dicho Sr. Benito Gonzales Sy Chiam a retrovendornos la finca arriba descrita; pero si transcurre dicho plazo de cinco (5) aos sin ejercitar al derecho de retracto que nos hemos reservado, entonces quedara esta venta absoluta e irrevocable. Language cannot be clearer. The purpose of the contract is expressed clearly in said quotation that there can certainly be not doubt as to the purpose of the plaintiff to sell the property in question, reserving the right only to repurchase the same. The intention to sell with the right to repurchase cannot be more clearly expressed. It will be noted from a reading of said sale of pacto de retro, that the vendor, recognizing the absolute sale of the property, entered into a contract with the purchaser by virtue of which she became the "tenant" of the purchaser. That contract of rent appears in said quoted document above as follows:

Credit Transactions

10

Tercero. Que durante el expresado termino del retracto tendremos en arrendamiento la finca arriba descrita, sujeto a condiciones siguientes: (a) El alquiler que nos obligamos a pagar por mensualidades vencidas a Don Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam y en su domicilio, sera de trescientos setenta y cinco pesos (P375) moneda filipina, cada mes. (b) El amillaramiento de la finca arrendada sera por cuenta de dicho Don Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam, asi como tambien la prima del seguro contra incendios, si le conviniera al referido Sr. Benito Gonzalez Sy Chiam asegurar dicha finca. From the foregoing, we are driven to the following conclusions: First, that the contract of pacto de retro is an absolute sale of the property with the right to repurchase and not a mortgage; and, second, that by virtue of the said contract the vendor became the tenant of the purchaser, under the conditions mentioned in paragraph 3 of said contact quoted above. It has been the uniform theory of this court, due to the severity of a contract of pacto de retro, to declare the same to be a mortgage and not a sale whenever the interpretation of such a contract justifies that conclusion. There must be something, however, in the language of the contract or in the conduct of the parties which shows clearly and beyond doubt that they intended the contract to be a "mortgage" and not a pacto de retro. (International Banking Corporation vs. Martinez, 10 Phil., 252; Padilla vs. Linsangan, 19 Phil., 65; Cumagun vs. Alingay, 19 Phil., 415; Olino vs. Medina, 13 Phil., 379; Manalo vs. Gueco, 42 Phil., 925; Velazquez vs. Teodoro, 46 Phil., 757; Villavs. Santiago, 38 Phil., 157.) We are not unmindful of the fact that sales with pacto de retro are not favored and that the court will not construe an instrument to one of sale with pacto de retro, with the stringent and onerous effect which follows, unless the terms of the document and the surrounding circumstances require it. While it is general rule that parol evidence is not admissible for the purpose of varying the terms of a contract, but when an issue is squarely presented that a contract does not express the intention of the parties, courts will, when a proper foundation is laid therefor, hear evidence for the purpose of ascertaining the true intention of the parties. In the present case the plaintiffs allege in their complaint that the contract in question is a pacto de retro. They admit that they signed it. They admit they sold the property in question with the right to repurchase it. The terms of the contract quoted by the plaintiffs to the defendant was a "sale" with pacto de retro, and the plaintiffs have shown no circumstance whatever which would justify us in construing said contract to be a mere "loan" with guaranty. In every case in which this court has construed a contract to be a mortgage or a loan instead of a sale with pacto de retro, it has done so, either because the terms of such contract were incompatible or inconsistent with the theory that said contract was one of purchase and sale. (Olino vs. Medina, supra; Padilla vs. Linsangan,supra; Manlagnit vs. Dy Puico, 34 Phil., 325; Rodriguez vs. Pamintuan and De Jesus, 37 Phil., 876.) In the case of Padilla vs. Linsangan the term employed in the contract to indicate the nature of the conveyance of the land was "pledged" instead of "sold". In the case of Manlagnit vs. Dy Puico, while the vendor used to the terms "sale and transfer with the right to repurchase," yet in said contract he described himself as a "debtor" the purchaser as a "creditor" and the contract as a "mortgage". In the case of Rodriguez vs. Pamintuan and De Jesusthe person

Credit Transactions

11

who executed the instrument, purporting on its face to be a deed of sale of certain parcels of land, had merely acted under a power of attorney from the owner of said land, "authorizing him to borrow money in such amount and upon such terms and conditions as he might deem proper, and to secure payment of the loan by a mortgage." In the case of Villa vs. Santiago (38 Phil., 157), although a contract purporting to be a deed of sale was executed, the supposed vendor remained in possession of the land and invested the money he had obtained from the supposed vendee in making improvements thereon, which fact justified the court in holding that the transaction was a mere loan and not a sale. In the case of Cuyugan vs. Santos (39 Phil., 970), the purchaser accepted partial payments from the vendor, and such acceptance of partial payments is absolutely incompatible with the idea of irrevocability of the title of ownership of the purchaser at the expiration of the term stipulated in the original contract for the exercise of the right of repurchase." Referring again to the right of the parties to vary the terms of written contract, we quote from the dissenting opinion of Chief Justice Cayetano S. Arellano in the case of Government of the Philippine Islands vs. Philippine Sugar Estates Development Co., which case was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States and the contention of the Chief Justice in his dissenting opinion was affirmed and the decision of the Supreme Court of the Philippine Islands was reversed. (See decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, June 3, 1918.)1 The Chief Justice said in discussing that question: According to article 1282 of the Civil Code, in order to judge of the intention of the contracting parties, consideration must chiefly be paid to those acts executed by said parties which are contemporary with and subsequent to the contract. And according to article 1283, however general the terms of a contract may be, they must not be held to include things and cases different from those with regard to which the interested parties agreed to contract. "The Supreme Court of the Philippine Islands held the parol evidence was admissible in that case to vary the terms of the contract between the Government of the Philippine Islands and the Philippine Sugar Estates Development Co. In the course of the opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States Mr. Justice Brandeis, speaking for the court, said: It is well settled that courts of equity will reform a written contract where, owing to mutual mistake, the language used therein did not fully or accurately express the agreement and intention of the parties. The fact that interpretation or construction of a contract presents a question of law and that, therefore, the mistake was one of law is not a bar to granting relief. . . . This court is always disposed to accept the construction which the highest court of a territory or possession has placed upon a local statute. But that disposition may not be yielded to where the lower court has clearly erred. Here the construction adopted was rested upon a clearly erroneous assumption as to an established rule of equity. . . . The burden of proof resting upon the appellant cannot be satisfied by mere preponderance of the evidence. It is settled that relief by way of reformation will not be granted unless the proof of mutual mistake be of the clearest and most satisfactory character. The evidence introduced by the appellant in the present case does not meet with that stringent requirement. There is not a word, a phrase, a sentence or a paragraph in the entire record, which justifies this court in holding that the said contract of pacto de retro is a mortgage and not a sale with the right to repurchase. Article 1281 of the Civil Code provides: "If the terms of a contract are clear and leave no doubt as to the intention of the contracting parties, the literal sense of its stipulations shall be followed." Article 1282 provides: "in order to judge as to the

Credit Transactions

12

intention of the contracting parties, attention must be paid principally to their conduct at the time of making the contract and subsequently thereto." We cannot thereto conclude this branch of our discussion of the question involved, without quoting from that very well reasoned decision of the late Chief Justice Arellano, one of the greatest jurists of his time. He said, in discussing the question whether or not the contract, in the case of Lichauco vs. Berenguer (20 Phil., 12), was apacto de retro or a mortgage: The public instrument, Exhibit C, in part reads as follows: "Don Macarion Berenguer declares and states that he is the proprietor in fee simple of two parcels of fallow unappropriated crown land situated within the district of his pueblo. The first has an area of 73 quiones, 8 balitas and 8 loanes, located in the sitio of Batasan, and its boundaries are, etc., etc. The second is in the sitio of Panantaglay, barrio of Calumpang has as area of 73 hectares, 22 ares, and 6 centares, and is bounded on the north, etc., etc." In the executory part of the said instrument, it is stated: 'That under condition of right to repurchase (pacto de retro) he sells the said properties to the aforementioned Doa Cornelia Laochangco for P4,000 and upon the following conditions: First, the sale stipulated shall be for the period of two years, counting from this date, within which time the deponent shall be entitled to repurchase the land sold upon payment of its price; second, the lands sold shall, during the term of the present contract, be held in lease by the undersigned who shall pay, as rental therefor, the sum of 400 pesos per annum, or the equivalent in sugar at the option of the vendor; third, all the fruits of the said lands shall be deposited in the sugar depository of the vendee, situated in the district of Quiapo of this city, and the value of which shall be applied on account of the price of this sale; fourth, the deponent acknowledges that he has received from the vendor the purchase price of P4,000 already paid, and in legal tender currency of this country . . .; fifth, all the taxes which may be assessed against the lands surveyed by competent authority, shall be payable by and constitute a charge against the vendor; sixth, if, through any unusual event, such as flood, tempest, etc., the properties hereinbefore enumerated should be destroyed, wholly or in part, it shall be incumbent upon the vendor to repair the damage thereto at his own expense and to put them into a good state of cultivation, and should he fail to do so he binds himself to give to the vendee other lands of the same area, quality and value.' xxx xxx xxx

The opponent maintained, and his theory was accepted by the trial court, that Berenguer's contract with Laochangco was not one of sale with right of repurchase, but merely one of loan secured by those properties, and, consequently, that the ownership of the lands in questions could not have been conveyed to Laochangco, inasmuch as it continued to be held by Berenguer, as well as their possession, which he had not ceased to enjoy. Such a theory is, as argued by the appellant, erroneous. The instrument executed by Macario Berenguer, the text of which has been transcribed in this decision, is very clear. Berenguer's heirs may not go counter to the literal tenor of the obligation, the exact expression of the consent of the contracting contained in the instrument, Exhibit C. Not

Credit Transactions

13

because the lands may have continued in possession of the vendor, not because the latter may have assumed the payment of the taxes on such properties, nor yet because the same party may have bound himself to substitute by another any one of the properties which might be destroyed, does the contract cease to be what it is, as set forth in detail in the public instrument. The vendor continued in the possession of the lands, not as the owner thereof as before their sale, but as the lessee which he became after its consummation, by virtue of a contract executed in his favor by the vendee in the deed itself, Exhibit C. Right of ownership is not implied by the circumstance of the lessee's assuming the responsibility of the payment is of the taxes on the property leased, for their payment is not peculiarly incumbent upon the owner, nor is such right implied by the obligation to substitute the thing sold for another while in his possession under lease, since that obligation came from him and he continues under another character in its possessiona reason why he guarantees its integrity and obligates himself to return the thing even in a case of force majeure. Such liability, as a general rule, is foreign to contracts of lease and, if required, is exorbitant, but possible and lawful, if voluntarily agreed to and such agreement does not on this account involve any sign of ownership, nor other meaning than the will to impose upon oneself scrupulous diligence in the care of a thing belonging to another. The purchase and sale, once consummated, is a contract which by its nature transfers the ownership and other rights in the thing sold. A pacto de retro, or sale with right to repurchase, is nothing but a personal right stipulated between the vendee and the vendor, to the end that the latter may again acquire the ownership of the thing alienated. It is true, very true indeed, that the sale with right of repurchase is employed as a method of loan; it is likewise true that in practice many cases occur where the consummation of a pacto de retro sale means the financial ruin of a person; it is also, unquestionable that in pacto de retro sales very important interests often intervene, in the form of the price of the lease of the thing sold, which is stipulated as an additional covenant. (Manresa, Civil Code, p. 274.) But in the present case, unlike others heard by this court, there is no proof that the sale with right of repurchase, made by Berenguer in favor of Laonchangco is rather a mortgage to secure a loan. We come now to a discussion of the second question presented above, and that is, stating the same in another form: May a tenant charge his landlord with a violation of the Usury Law upon the ground that the amount of rent he pays, based upon the real value of the property, amounts to a usurious rate of interest? When the vendor of property under a pacto de retro rents the property and agrees to pay a rental value for the property during the period of his right to repurchase, he thereby becomes a "tenant" and in all respects stands in the same relation with the purchaser as a tenant under any other contract of lease. The appellant contends that the rental price paid during the period of the existence of the right to repurchase, or the sum of P375 per month, based upon the value of the property, amounted to usury. Usury, generally speaking, may be defined as contracting for or receiving something in excess of the amount allowed by law for the loan or forbearance of moneythe taking of more interest for the use of money than the law allows. It seems that the taking of interest for the loan of money, at least the taking of excessive interest has been regarded with abhorrence from the earliest times. (Dunham vs. Gould, 16 Johnson [N. Y.], 367.) During the middle ages the people of England, and especially the English Church, entertained the opinion, then,

Credit Transactions

14

current in Europe, that the taking of any interest for the loan of money was a detestable vice, hateful to man and contrary to the laws of God. (3 Coke's Institute, 150; Tayler on Usury, 44.) Chancellor Kent, in the case of Dunham vs. Gould, supra, said: "If we look back upon history, we shall find that there is scarcely any people, ancient or modern, that have not had usury laws. . . . The Romans, through the greater part of their history, had the deepest abhorrence of usury. . . . It will be deemed a little singular, that the same voice against usury should have been raised in the laws of China, in the Hindu institutes of Menu, in the Koran of Mahomet, and perhaps, we may say, in the laws of all nations that we know of, whether Greek or Barbarian." The collection of a rate of interest higher than that allowed by law is condemned by the Philippine Legislature (Acts Nos. 2655, 2662 and 2992). But is it unlawful for the owner of a property to enter into a contract with the tenant for the payment of a specific amount of rent for the use and occupation of said property, even though the amount paid as "rent," based upon the value of the property, might exceed the rate of interest allowed by law? That question has never been decided in this jurisdiction. It is one of first impression. No cases have been found in this jurisdiction answering that question. Act No. 2655 is "An Act fixing rates of interest upon 'loans' and declaring the effect of receiving or taking usurious rates." It will be noted that said statute imposes a penalty upon a "loan" or forbearance of any money, goods, chattels or credits, etc. The central idea of said statute is to prohibit a rate of interest on "loans." A contract of "loan," is very different contract from that of "rent". A "loan," as that term is used in the statute, signifies the giving of a sum of money, goods or credits to another, with a promise to repay, but not a promise to return the same thing. To "loan," in general parlance, is to deliver to another for temporary use, on condition that the thing or its equivalent be returned; or to deliver for temporary use on condition that an equivalent in kind shall be returned with a compensation for its use. The word "loan," however, as used in the statute, has a technical meaning. It never means the return of the same thing. It means the return of an equivalent only, but never the same thing loaned. A "loan" has been properly defined as an advance payment of money, goods or credits upon a contract or stipulation to repay, not to return, the thing loaned at some future day in accordance with the terms of the contract. Under the contract of "loan," as used in said statute, the moment the contract is completed the money, goods or chattels given cease to be the property of the former owner and becomes the property of the obligor to be used according to his own will, unless the contract itself expressly provides for a special or specific use of the same. At all events, the money, goods or chattels, the moment the contract is executed, cease to be the property of the former owner and becomes the absolute property of the obligor. A contract of "loan" differs materially from a contract of "rent." In a contract of "rent" the owner of the property does not lose his ownership. He simply loses his control over the property rented during the period of the contract. In a contract of "loan" the thing loaned becomes the property of the obligor. In a contract of "rent" the thing still remains the property of the lessor. He simply loses control of the same in a limited way during the period of the contract of "rent" or lease. In a contract of "rent" the relation between the contractors is that of landlord and tenant. In a contract of "loan" of money, goods, chattels or credits, the relation between the parties is that of obligor and obligee. "Rent" may be defined as the compensation either in money, provisions, chattels, or labor, received by the owner of the soil from the occupant thereof. It is defined as the return or compensation for the possession of some corporeal inheritance, and is a profit issuing out of lands or tenements, in return for their use. It is that, which is to paid for the use of land, whether in money, labor or other thing agreed upon. A contract of "rent" is a contract by which one of the parties delivers to the other some

Credit Transactions

15

nonconsumable thing, in order that the latter may use it during a certain period and return it to the former; whereas a contract of "loan", as that word is used in the statute, signifies the delivery of money or other consumable things upon condition of returning an equivalent amount of the same kind or quantity, in which cases it is called merely a "loan." In the case of a contract of "rent," under the civil law, it is called a "commodatum." From the foregoing it will be seen that there is a while distinction between a contract of "loan," as that word is used in the statute, and a contract of "rent" even though those words are used in ordinary parlance as interchangeable terms. The value of money, goods or credits is easily ascertained while the amount of rent to be paid for the use and occupation of the property may depend upon a thousand different conditions; as for example, farm lands of exactly equal productive capacity and of the same physical value may have a different rental value, depending upon location, prices of commodities, proximity to the market, etc. Houses may have a different rental value due to location, conditions of business, general prosperity or depression, adaptability to particular purposes, even though they have exactly the same original cost. A store on the Escolta, in the center of business, constructed exactly like a store located outside of the business center, will have a much higher rental value than the other. Two places of business located in different sections of the city may be constructed exactly on the same architectural plan and yet one, due to particular location or adaptability to a particular business which the lessor desires to conduct, may have a very much higher rental value than one not so located and not so well adapted to the particular business. A very cheap building on the carnival ground may rent for more money, due to the particular circumstances and surroundings, than a much more valuable property located elsewhere. It will thus be seen that the rent to be paid for the use and occupation of property is not necessarily fixed upon the value of the property. The amount of rent is fixed, based upon a thousand different conditions and may or may not have any direct reference to the value of the property rented. To hold that "usury" can be based upon the comparative actual rental value and the actual value of the property, is to subject every landlord to an annoyance not contemplated by the law, and would create a very great disturbance in every business or rural community. We cannot bring ourselves to believe that the Legislature contemplated any such disturbance in the equilibrium of the business of the country. In the present case the property in question was sold. It was an absolute sale with the right only to repurchase. During the period of redemption the purchaser was the absolute owner of the property. During the period of redemption the vendor was not the owner of the property. During the period of redemption the vendor was a tenant of the purchaser. During the period of redemption the relation which existed between the vendor and the vendee was that of landlord and tenant. That relation can only be terminated by a repurchase of the property by the vendor in accordance with the terms of the said contract. The contract was one of rent. The contract was not a loan, as that word is used in Act No. 2655. As obnoxious as contracts of pacto de retro are, yet nevertheless, the courts have no right to make contracts for parties. They made their own contract in the present case. There is not a word, a phrase, a sentence or paragraph, which in the slightest way indicates that the parties to the contract in question did not intend to sell the property in question absolutely, simply with the right to repurchase. People who make their own beds must lie thereon. What has been said above with reference to the right to modify contracts by parol evidence, sufficiently answers the third questions presented above. The language of the contract is explicit, clear, unambiguous and beyond question. It expresses the exact intention of the

Credit Transactions

16

parties at the time it was made. There is not a word, a phrase, a sentence or paragraph found in said contract which needs explanation. The parties thereto entered into said contract with the full understanding of its terms and should not now be permitted to change or modify it by parol evidence. With reference to the improvements made upon said property by the plaintiffs during the life of the contract, Exhibit C, there is hereby reserved to the plaintiffs the right to exercise in a separate action the right guaranteed to them under article 361 of the Civil Code. For all of the foregoing reasons, we are fully persuaded from the facts of the record, in relation with the law applicable thereto, that the judgment appealed from should be and is hereby affirmed, with costs. So ordered. Avancea, C. J., Street, Villamor, Romualdez and Villa-Real, JJ., concur.

G.R. No. 112485

August 9, 2001

EMILIA MANZANO, petitioner, vs. MIGUEL PEREZ SR., LEONCIO PEREZ, MACARIO PEREZ, FLORENCIO PEREZ, NESTOR PEREZ, MIGUEL PEREZ JR. and GLORIA PEREZ,respondents. PANGANIBAN, J.: Courts decide cases on the basis of the evidence presented by the parties. In the assessment of the facts, reason and logic are used. In civil cases, the party that presents a preponderance of convincing evidence wins. The Case Before us is a Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, assailing the March 31, 1993 Decision1 of the Court of Appeals (CA)2 in CA-GR CY No. 32594. The dispositive part of the Decision reads: "WHEREFORE, the judgment appealed from is hereby REVERSED and another one is entered dismissing plaintiff's complaint." On the other hand, the Judgment3 reversed by the CA ruled in this wise: "WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered: 1) Declaring the two 'Kasulatan ng Bilihang Tuluyan' (Exh. 'J' & 'K') over the properties in question void or simulated; 2) Declaring the two 'Kasulatan ng Bilihang Tuluyan' (Exh. 'J' & 'K') over the properties in question rescinded; 3) Ordering the defendants Miguel Perez, Sr., Macario Perez, Leoncio Perez, Florencio Perez, Miguel Perez, Jr., Nestor Perez and Gloria Perez to execute an Extra Judicial

Credit Transactions

17

Partition with transfer over the said residential lot and house, now covered and described in Tax Declaration Nos. 1993 and 1994, respectively in the name of Nieves Manzano (Exh. 'Q' & 'P'), subject matter of this case, in favor of plaintiff Emilia Manzano; 4) Ordering the defendants to pay plaintiff: a) P25,000.00 as moral damages; b) P10,000.00 as exemplary damages; c) P15,000.00 as and for [a]ttorney's fees; and d) to pay the cost of the suit."4 The Motion for Reconsideration filed by petitioner before the CA was denied in a Resolution dated October 28, 1993.5 The Facts The facts of the case are summarized by the Court of Appeals as follows: "[Petitioner] Emilia Manzano in her Complaint alleged that she is the owner of a residential house and lot, more particularly described hereunder: 'A parcel of residential lot (Lots 1725 and 1726 of the Cadastral Survey of Siniloan), together with all the improvements thereon, situated at General Luna Street, Siniloan, Laguna. Bounded on the North by Callejon; on the East, by [a] town river; on the South by Constancia Adofina; and on the West by Gen. Luna Street. Containing an area of 130 square meters more or less, covered by Tax Dec. No. 9583 and assessed at P1,330.00. 'A residential house of strong mixed materials and G.I. iron roofing, with a floor area of 40 square meters, more or less. Also covered by Tax No. 9583.' "In 1979, Nieves Manzano, sister of the [petitioner] and predecessor-in-interest of the herein [private respondents], allegedly borrowed the aforementioned property as collateral for a projected loan. The [petitioner] acceded to the request of her sister upon the latter's promise that she [would] return the property immediately upon payment of her loan. "Pursuant to their understanding, the [petitioner] executed two deeds of conveyance for the sale of the residential lot on 22 January 1979 (Exhibit 'J') and the sale of the house erected thereon on 2 February 1979 (Exhibit 'K'), both for a consideration of P1.00 plus other valuables allegedly received by her from Nieves Manzano. "On 2 April 1979, Nieves Manzano, together with her husband, [respondent] Miguel Perez, Sr., and her son, [respondent] Macario Perez, obtained a loan from the Rural Bank of Infanta, Inc. in the sum of P30,000.00. To secure payment of their indebtedness, they executed a Real Estate Mortgage (Exhibit 'A') over the subject property in favor of the bank.

Credit Transactions

18

"Nieves Manzano died on 18 December 1979 leaving her husband and children as heirs. These heirs, [respondents] herein, allegedly refused to return the subject property to the [petitioner] even after the payment of their loan with the Rural Bank (Exhibit 'B'). "The [petitioner] alleged that sincere efforts to settle the dispute amicably failed and that the unwarranted refusal of the [respondents] to return the property caused her sleepless nights, mental shock and social humiliation. She was, likewise, allegedly constrained to engage the services of a counsel to protect her proprietary rights. "The [petitioner] sought the annulment of the deeds of sale and execution of a deed of transfer or reconveyance of the subject property in her favor, the award of moral damages of not less than P50,000.00, exemplary damages of P10,000.00, attorney's fees of P10,000.00 plus P500.00 per court appearance, and costs of suit. "In seeking the dismissal of the complaint, the [respondents] countered that they are the owners of the property in question being the legal heirs of Nieves Manzano who purchased the same from the [petitioner] for value and in good faith, as shown by the deeds of sale which contain the true agreements between the parties therein; that except for the [petitioner's] bare allegations, she failed to show any proof that the transaction she entered into with her sister was a loan and not a sale. "By way of special and affirmative defense, the [respondents] argued that what the parties to the [sale] agreed upon was to resell the property to the [petitioner] after the payment of the loan with the Rural Bank. But since the [respondents] felt that the property is the only memory left by their predecessor-in-interest, they politely informed the [petitioner] of their refusal to sell the same. The [respondents] also argued that the [petitioner] is now estopped from questioning their ownership after seven (7) years from the consummation of the sale. "As a proximate result of the filing of this alleged baseless and malicious suit, the [respondents] prayed as counterclaim the award of moral damages in the amount of P10,000.00 each, exemplary damages in an amount as may be warranted by the evidence on record, attorney's fees of P10,000.00 plus P500.00 per appearance in court and costs of suit. "In ruling for the [petitioner], the court a guo considered the following: 'First, the properties in question after [they have] been transferred to Nieves Manzano, the same were mortgaged in favor of the Rural Bank of Infante, Inc. (Exh. 'A') to secure payment of the loan extended to Macario Perez.' 'Second, the documents covering said properties which were given to the bank as collateral of said loan, upon payment and [release] to the [private respondents], were returned to [petitioner] by Florencio Perez, one of the [private respondents].' '[These] uncontroverted facts [are] a clear recognition [by private respondents] that [petitioner] is the owner of the properties in question.' xxx xxx xxx "'

Credit Transactions

19

'Third, [respondents'] pretense of ownership of the properties in question is belied by their failure to present payment of real estate taxes [for] said properties, and it is on [record] that [petitioner] has been paying the real estate taxes [on] the same (Exh. 'T', 'V', 'V-1', 'V-2' & 'V- 3')." xxx xxx xxx 'Fourth, [respondents] confirmed the fact that [petitioner] went to the house in question and hacked the stairs. According to [petitioner] she did it for failure of the [respondents] to return and vacate the premises. [Respondents] did not file any action against her.' 'This is a clear indication also that they (respondents) recognized [petitioner] as owner of said properties.' xxx xxx xxx 'Fifth, the Cadastral Notice of said properties were in the name of [petitioner] and the same was sent to her (Exh. 'F' & 'G'). xxx xxx xxx 'Sixth, upon request of the [petitioner] to return said properties to her, [respondents] did promise and prepare an Extra Judicial Partition with Sale over said properties in question, however the same did not materialize. The other heirs of Nieves Manzano did not sign." xxx xxx xxx 'Seventh, uncontroverted is the fact that the consideration [for] the alleged sale of the properties in question is P1.00 and other things of value. [Petitioner] denies she has received any consideration for the transfer of said properties, and the [respondents] have not presented evidence to belie her testimony."6 Ruling of the Court of Appeals The Court of Appeals was not convinced by petitioner's claim that there was a supposed oral agreement of commodatum over the disputed house and lot. Neither was it persuaded by her allegation that respondents' predecessor-in-interest had given no consideration for the sale of the property in the latter's favor. It explained as follows: "To begin with, if the plaintiff-appellee remained as the rightful owner of the subject property, she would not have agreed to reacquire one-half thereof for a consideration of P10,000.00 (Exhibit 'U-1'). This is especially true if we are to accept her assertion that Nieves Manzano did not purchase the property for value. More importantly, if the agreement was to merely use plaintiff's property as collateral in a mortgage loan, it was not explained why physical possession of the house and lot had to be with the supposed vendee and her family who even built a pigpen on the lot (p. 6, TSN, June 11, 1990). A mere execution of the document transferring title in the latter's name would suffice for the purpose.

Credit Transactions

20

"The alleged failure of the defendants-appellants to present evidence of payment of real estate taxes cannot prejudice their cause. Realty tax payment of property is not conclusive evidence of ownership (Director of Lands vs. Intermediate Appellate Court, 195 SCRA 38). Tax receipts only become strong evidence of ownership when accompanied by proof of actual possession of the property (Tabuena vs. Court of Appeals, 196 SCRA 650). "In this case, plaintiff-appell[ee] was not in possession of the subject property. The defendant-appellants were the ones in actual occupation of the house and lot which as aforestated was unnecessary if the real agreement was merely to lend the property to be used as collateral. Moreover, the plaintiff-appellee began paying her taxes only in 1986 after the instant complaint ha[d] been instituted (Exhibits 'V', 'V-1', 'V-2', 'V-3' and 'T'), and are, therefore, self-serving. "Significantly, while plaintiff-appellee was still the owner of the subject property in 1979 (Exhibit 'I'), the Certificate of Tax Declaration issued by the Office of the Municipal Treasurer on 8 August 1990 upon the request of the plaintiff-appellee herself (Exhibit 'W') named Nieves Manzano as the owner and possessor of the property in question. Moreover, Tax Declaration No. 9589 in the name of Nieves Manzano (Exhibits 'D' and 'D-1 ') indicates that the transfer of the subject property was based on the Absolute Sale executed before Notary Public Alfonso Sanvictores, duly recorded in his notarial book as Document No. 3157, Page 157, Book No. II. Tax Declaration No[s]. 9633 (Exhibit 'H'), 1994 (Exhibit 'P'), 1993 (Exhibit 'Q') are all in the name of Nieves Manzano. "There is always the presumption that a written contract [is] for a valuable consideration (Section 5 (r), Rule 131 of the Rules of Court; Gamaitan vs. Court of Appeals, 200 SCRA 37). The execution of a deed purporting to convey ownership of a realty is in itself prima facie evidence of the existence of a valuable consideration and xxx the party alleging lack of consideration has the burden of proving such allegation (Caballero, et al. vs. Caballero, et al., C.A. 45 O.G. 2536). "The consideration [for] the questioned [sale] is not the One (P1.00) Peso alone but also the other valuable considerations. Assuming that such consideration is suspiciously insufficient, this circumstance alone, is not sufficient to invalidate the sale. The inadequacy of the monetary consideration does not render a conveyance null and void, for the vendor's liberality may be a sufficient cause for a valid contract (Ong vs. Ong, 139 SCRA 133)."7 Hence, this Petition.8 Issues Petitioner submits the following grounds in support of her cause:9 "1. The Court of Appeals erred in failing to consider that: A) The introduction of petitioner's evidence is proper under the parol evidence rule. B) The rules on admission by silence apply in the case at bar.

Credit Transactions

21

C) Petitioner is entitled to the reliefs prayed for. "2. The Court of Appeals erred in reversing the decision of the trial court whose factual findings are entitled to great respect since it was able to observe and evaluate the demeanor of the witnesses."10 In sum, the main issue is whether the agreement between the parties was a commodatum or an absolute sale. The Court's Ruling The Petition has no merit. Main Issue: Sale or Commodatum Obviously, the issue in this case is enveloped by a conflict in factual perception, which is ordinarily not reviewable in a petition under Rule 45. But the Court is constrained to resolve it, because the factual findings of the Court of Appeals are contrary to those of the trial court.11 Preliminarily, petitioner contends that the CA erred in rejecting the introduction of her parol evidence. A reading of the assailed Decision shows, however, that an elaborate discussion of the parol evidence rule and its exceptions was merely given as a preface by the appellate court. Nowhere therein did it consider petitioner's evidence as improper under the said rule. On the contrary, it considered and weighed each and every piece thereof. Nonetheless, it was not persuaded, as explained in the multitude of reasons explicitly stated in its Decision. This Court finds no cogent reason to disturb the findings and conclusions of the Court of Appeals. Upon close examination of the records, we find that petitioner has failed to discharge her burden of proving her case by a preponderance of evidence. This concept refers to evidence that has greater weight or is more convincing than that which is offered in opposition; at bottom, it means probability of truth.12 In the case at bar, petitioner has presented no convincing proof of her continued ownership of the subject property. In addition to her own oral testimony, she submitted proof of payment of real property taxes. But that payment, which was made only after her Complaint had already been lodged before the trial court, cannot be considered in her favor for being self-serving, as aptly explained by the CA. Neither can we give weight to her allegation that respondent's possession of the subject property was merely by virtue of her tolerance. Bare allegations, unsubstantiated by evidence, are not equivalent to proof under our Rules.13 On the other hand, respondents presented two Deeds of Sale, which petitioner executed in favor of the former's predecessor-in-interest. Both Deeds - for the residential lot and for the house erected thereon - were each in consideration of P1.00 "plus other valuables." Having been notarized, they are presumed to have been duly executed. Also, issued in favor of respondents' predecessor-in-interest the day after the sale was Tax Declaration No. 9589, which covered the property. The facts alleged by petitioner in her favor are the following: (1) she inherited the subject house and lot from her parents, with her siblings waiving in her favor their claim over the same; (2) the property was mortgaged to secure a loan of P30,000 taken in the names of Nieves Manzano Perez and Respondent Miguel Perez; (3) upon full payment of the loan, the

Credit Transactions

22

documents pertaining to the house and lot were returned by Respondent Florencio Perez to petitioner; (4) three of the respondents were signatories to a document transferring one half of the property to Emilia Manzano in consideration of the sum of ten thousand pesos, although the transfer did not materialize because of the refusal of the other respondents to sign the document; and (5) petitioner hacked the stairs of the subject house, yet no case was filed against her. 1wphi1.nt These matters are not, however, convincing indicators of petitioner's ownership of the house and lot. On the contrary, they even support the claim of respondents. Indeed, how could one of them have obtained a mortgage over the property, without having dominion over it? Why would they execute a reconveyance of one half of it in favor of petitioner? Why would the latter have to pay P10,000 for that portion if, as she claims, she owns the whole? Pitted against respondents' evidence, that of petitioner awfully pales. Oral testimony cannot, as a rule, prevail over a written agreement of the parties.14In order to contradict the facts contained in a notarial document, such as the two "Kasulatan ng Bilihang Tuluyan" in this case, as well as the presumption of regularity in the execution thereof, there must be clear and convincing evidence that is more than merely preponderant.15 Here, petitioner has failed to come up with even a preponderance of evidence to prove her claim. Courts are not blessed with the ability to read what goes on in the minds of people. That is why parties to a case are given all the opportunity to present evidence to help the courts decide on who are telling the truth and who are lying, who are entitled to their claim and who are not. The Supreme Court cannot depart from these guidelines and decide on the basis of compassion alone because, aside from being contrary to the rule of law and our judicial system, this course of action would ultimately lead to anarchy. We reiterate, the evidence offered by petitioner to prove her claim is sadly lacking. Jurisprudence on the subject matter, when applied thereto, points to the existence of a sale, not a commodatum over the subject house and lot. WHEREFORE, the Petition is hereby DENIED and the assailed Decision AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioner. SO ORDERED.

G.R. No. 146364

June 3, 2004

COLITO T. PAJUYO, petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and EDDIE GUEVARRA, respondents. CARPIO, J.: The Case Before us is a petition for review1 of the 21 June 2000 Decision2 and 14 December 2000 Resolution of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 43129. The Court of Appeals set aside

Credit Transactions

23

the 11 November 1996 decision3 of the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 81,4affirming the 15 December 1995 decision5 of the Metropolitan Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 31.6 The Antecedents In June 1979, petitioner Colito T. Pajuyo ("Pajuyo") paid P400 to a certain Pedro Perez for the rights over a 250-square meter lot in Barrio Payatas, Quezon City. Pajuyo then constructed a house made of light materials on the lot. Pajuyo and his family lived in the house from 1979 to 7 December 1985. On 8 December 1985, Pajuyo and private respondent Eddie Guevarra ("Guevarra") executed a Kasunduan or agreement. Pajuyo, as owner of the house, allowed Guevarra to live in the house for free provided Guevarra would maintain the cleanliness and orderliness of the house. Guevarra promised that he would voluntarily vacate the premises on Pajuyos demand. In September 1994, Pajuyo informed Guevarra of his need of the house and demanded that Guevarra vacate the house. Guevarra refused. Pajuyo filed an ejectment case against Guevarra with the Metropolitan Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 31 ("MTC"). In his Answer, Guevarra claimed that Pajuyo had no valid title or right of possession over the lot where the house stands because the lot is within the 150 hectares set aside by Proclamation No. 137 for socialized housing. Guevarra pointed out that from December 1985 to September 1994, Pajuyo did not show up or communicate with him. Guevarra insisted that neither he nor Pajuyo has valid title to the lot. On 15 December 1995, the MTC rendered its decision in favor of Pajuyo. The dispositive portion of the MTC decision reads: WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered for the plaintiff and against defendant, ordering the latter to: A) vacate the house and lot occupied by the defendant or any other person or persons claiming any right under him; B) pay unto plaintiff the sum of THREE HUNDRED PESOS (P300.00) monthly as reasonable compensation for the use of the premises starting from the last demand; C) pay plaintiff the sum of P3,000.00 as and by way of attorneys fees; and D) pay the cost of suit. SO ORDERED.7 Aggrieved, Guevarra appealed to the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 81 ("RTC"). On 11 November 1996, the RTC affirmed the MTC decision. The dispositive portion of the RTC decision reads:

Credit Transactions

24

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Court finds no reversible error in the decision appealed from, being in accord with the law and evidence presented, and the same is hereby affirmed en toto. SO ORDERED.8 Guevarra received the RTC decision on 29 November 1996. Guevarra had only until 14 December 1996 to file his appeal with the Court of Appeals. Instead of filing his appeal with the Court of Appeals, Guevarra filed with the Supreme Court a "Motion for Extension of Time to File Appeal by Certiorari Based on Rule 42" ("motion for extension"). Guevarra theorized that his appeal raised pure questions of law. The Receiving Clerk of the Supreme Court received the motion for extension on 13 December 1996 or one day before the right to appeal expired. On 3 January 1997, Guevarra filed his petition for review with the Supreme Court. On 8 January 1997, the First Division of the Supreme Court issued a Resolution9 referring the motion for extension to the Court of Appeals which has concurrent jurisdiction over the case. The case presented no special and important matter for the Supreme Court to take cognizance of at the first instance. On 28 January 1997, the Thirteenth Division of the Court of Appeals issued a Resolution10 granting the motion for extension conditioned on the timeliness of the filing of the motion. On 27 February 1997, the Court of Appeals ordered Pajuyo to comment on Guevaras petition for review. On 11 April 1997, Pajuyo filed his Comment. On 21 June 2000, the Court of Appeals issued its decision reversing the RTC decision. The dispositive portion of the decision reads: WHEREFORE, premises considered, the assailed Decision of the court a quo in Civil Case No. Q-96-26943 is REVERSED andSET ASIDE; and it is hereby declared that the ejectment case filed against defendant-appellant is without factual and legal basis. SO ORDERED.11 Pajuyo filed a motion for reconsideration of the decision. Pajuyo pointed out that the Court of Appeals should have dismissed outright Guevarras petition for review because it was filed out of time. Moreover, it was Guevarras counsel and not Guevarra who signed the certification against forum-shopping. On 14 December 2000, the Court of Appeals issued a resolution denying Pajuyos motion for reconsideration. The dispositive portion of the resolution reads: WHEREFORE, for lack of merit, the motion for reconsideration is hereby DENIED. No costs. SO ORDERED.12 The Ruling of the MTC

Credit Transactions

25

The MTC ruled that the subject of the agreement between Pajuyo and Guevarra is the house and not the lot. Pajuyo is the owner of the house, and he allowed Guevarra to use the house only by tolerance. Thus, Guevarras refusal to vacate the house on Pajuyos demand made Guevarras continued possession of the house illegal. The Ruling of the RTC The RTC upheld the Kasunduan, which established the landlord and tenant relationship between Pajuyo and Guevarra. The terms of the Kasunduan bound Guevarra to return possession of the house on demand. The RTC rejected Guevarras claim of a better right under Proclamation No. 137, the Revised National Government Center Housing Project Code of Policies and other pertinent laws. In an ejectment suit, the RTC has no power to decide Guevarras rights under these laws. The RTC declared that in an ejectment case, the only issue for resolution is material or physical possession, not ownership. The Ruling of the Court of Appeals The Court of Appeals declared that Pajuyo and Guevarra are squatters. Pajuyo and Guevarra illegally occupied the contested lot which the government owned. Perez, the person from whom Pajuyo acquired his rights, was also a squatter. Perez had no right or title over the lot because it is public land. The assignment of rights between Perez and Pajuyo, and the Kasunduan between Pajuyo and Guevarra, did not have any legal effect. Pajuyo and Guevarra are in pari delicto or in equal fault. The court will leave them where they are. The Court of Appeals reversed the MTC and RTC rulings, which held that the Kasunduan between Pajuyo and Guevarra created a legal tie akin to that of a landlord and tenant relationship. The Court of Appeals ruled that the Kasunduan is not a lease contract but acommodatum because the agreement is not for a price certain. Since Pajuyo admitted that he resurfaced only in 1994 to claim the property, the appellate court held that Guevarra has a better right over the property under Proclamation No. 137. President Corazon C. Aquino ("President Aquino") issued Proclamation No. 137 on 7 September 1987. At that time, Guevarra was in physical possession of the property. Under Article VI of the Code of Policies Beneficiary Selection and Disposition of Homelots and Structures in the National Housing Project ("the Code"), the actual occupant or caretaker of the lot shall have first priority as beneficiary of the project. The Court of Appeals concluded that Guevarra is first in the hierarchy of priority. In denying Pajuyos motion for reconsideration, the appellate court debunked Pajuyos claim that Guevarra filed his motion for extension beyond the period to appeal. The Court of Appeals pointed out that Guevarras motion for extension filed before the Supreme Court was stamped "13 December 1996 at 4:09 PM" by the Supreme Courts Receiving Clerk. The Court of Appeals concluded that the motion for extension bore a date, contrary to Pajuyos claim that the motion for extension was undated. Guevarra filed the motion for extension on time on 13 December 1996 since he filed the motion one day before the expiration of the reglementary period on 14 December 1996. Thus, the motion for

Credit Transactions

26