Professional Documents

Culture Documents

North Pacific Temperate Rainforests: Ecology and Conservation

Uploaded by

University of Washington PressCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

North Pacific Temperate Rainforests: Ecology and Conservation

Uploaded by

University of Washington PressCopyright:

Available Formats

NORTH

PACIFIC

TEMPERATE

RAINFORESTS

Edited by

oovoo n. ovis

& ion . scnor

Ecology & Conservation

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

North Pacific temPerate raiNforests

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

North

Pacific

Temperate

Rainforests

Ecology & Conservation

Edited by

gordoN h. oriaNs and

johN W. schoeN

auduboN alaska and

the Nature coNservaNcy of alaska

in association with

uNiversity of WashiNgtoN Press

Seattle and London

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

2013 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

18 17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechani-

cal, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or

retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

auduboN alaska

441 West Fifth Ave., Suite 300

Anchorage, ak 99501

ak.audubon.org

the Nature coNservaNcy iN alaska

715 L Street, Suite 200

Anchorage, ak 99501

www.nature.org

uNiversity of WashiNgtoN Press

Po Box 50096, Seattle, Wa 98145, usa

www.washington.edu/uwpress

library of coNgress catalogiNg-iN-PublicatioN data

North Pacifc temperate rainforests : ecology and conservation /

edited by Gordon Orians and John Schoen.

pages cm

isbN 978-0-295-99261-7 (hardback)

1. Temperate rain forest ecologyBritish Colombia. 2. Temperate

rain forest conservationBritish Colombia. 3. Temperate rain

forest ecologyAlaska. 4. Temperate rain forest conservation

Alaska. I. Orians, Gordon H., editor of compilation. II. Schoen,

John W., editor of compilation.

sd146.b7N67 2013 577.34dc23 2013007835

Te paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the mini-

mum requirements of American National Standard for Information

SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials,

aNsi Z39.48 1984.

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

to johN caouette

it is rare iNdeed WheN a scieNtist overturNs a Widely held

paradigm, but John Caouette did. John transformed the dominant method

of describing and mapping coastal forests in southeastern Alaska from an

industrial inventory of timber volume to an ecological framework of tree

size and stand density that more accurately refects the variety of key eco-

logical functions, habitat associations, and locations of rare forest types

across the landscape. In his methodical way, Johns work focused our

attention on characteristic patterns of forest structure that illustrated

underlying ecological processes and provided a very pragmatic approach

to forest management and conservation planning. He was a skilled statisti-

cian with the uncommon eye of a naturalist, ever helpful in providing

insightful discussion, guidance, and support. John was a valued colleague

with tremendous dedication to his work, yet even higher dedication to his

family, friends, and community. John is and will continue to be missed

greatly, and this book is dedicated to him.

Dave Albert

Te Nature Conservancy

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

coNteNts

Preface and Acknowledgments ix

Gordon Orians and John Schoen

1 Introduction 3

Gordon H. Orians, John W. Schoen, Jerry F. Franklin,

and Andy MacKinnon

2 Island Life: Coming to Grips with the Insular Nature of

Southeast Alaska and Adjoining Coastal British Columbia 19

Joseph A. Cook and Stephen O. MacDonald

3 Riparian Ecology, Climate Change, and Management

in North Pacifc Coastal Rainforests 43

Rick T. Edwards, David V. DAmore, Erik Norberg, and Frances Biles

4 Natural Disturbance Patterns in the Temperate Rainforests

of Southeast Alaska and Adjacent British Columbia 73

Paul Alaback, Gregory Nowacki, and Sari Saunders

5 Indigenous and Commercial Uses of the Natural Resources

of the North Pacifc Rainforest with a Focus on Southeast

Alaska and Haida Gwaii 89

Lisa K. Crone and Joe R. Mehrkens

Photo Gallery 127

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

6 Succession Debt and Roads: Short- and Long-Term Efects

of Timber Harvest on a Large-Mammal Predator-Prey

Community in Southeast Alaska 143

David K. Person and Todd J. Brinkman

7 Concepts of Conservation Biology Applied to Wildlife

in Old-Forest Ecosystems, with Special Reference to

Southeast Alaska and Northern Coastal British Columbia 168

Bruce G. Marcot

8 Why Watersheds: Evaluating the Protection of Undeveloped

Watersheds as a Conservation Strategy in Northwestern

North America 189

Ken Lertzman and Andy MacKinnon

9 Variable Retention Harvesting in North Pacifc

Temperate Rainforests 227

William J. Beese

10 Synthesis 253

Gordon H. Orians, John W. Schoen, Jerry F. Franklin,

and Andy MacKinnon

Literature Cited 293

Author Biographies 361

Index 369

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

ix

Preface aNd ackNoWledgmeNts

this Project Was first coNceived iN 2007 to exPaNd scieN-

tifc awareness and understanding of the North Pacifc temperate rain-

forest ecosystem and the Tongass National Forest by inviting key scientists

to participate in a science cruise through a portion of the Tongass. Te goal

of the expedition (completed in May 2008) was to conduct a feld-based

peer review of the Audubon AlaskaTe Nature Conservancy (TNC) con-

servation assessment and resource synthesis for southeast Alaska and

the Tongass National Forest. J. Schoen (Audubon) and D. Albert (TNC)

hosted eight scientists (P. Alaback, University of Montana; J. Cook, Uni-

ver sity of New Mexico; M. Kirchhof, Alaska Department of Fish and

Game; A. MacKinnon, British Columbia Forest Service; M. Nie, Univer sity

of Montana; B. Noon, Colorado State University; G. Orians, University of

Wash ington; and D. Secord, Wilburforce Foundation) on a cruise around

northeastern Chichagof Island.

Tis group of scientists also served as a steering committee for a sci-

ence workshop that was held in Juneau, Alaska, in February 2009. It was

sponsored jointly by Audubon Alaska and Te Nature Conservancy, with

agency cooperation from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, USDA

Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Alaska Chapter of

Te Wildlife Society. Te purpose of the workshop and public conference

was to discuss opportunities for incorporating fundamental concepts of

conservation biology into management strategies for conserving the bio-

diversity and ecological integrity of the Tongass National Forest. Te two-

day workshop featured eight invited papers with focused discussions

under the Dahlem Conference framework, which consisted of a small

group of participants invited to thoroughly discuss several agreed-upon

issues and themes. Each paper was provided to all invited participants four

weeks prior to the workshop, and two invited commentators (for each

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

x oriaNs aNd schoeN

paper), with expertise on that topic, also provided written comments. Te

presenters included seven senior authors (P. Alaback, W. Beese, J. Cook, L.

Crone, K. Lertzman, B. Marcot, and D. Person) of the focal papers included

in this book and D. DAmore (a coauthor with senior author R. Edwards).

In addition, the following scientists provided written commentary on each

of the presented papers: D. Albert, S. N. Dawson, J. Franklin, S. Gende, T.

Hanley, K. Hastings, K. Koski, A. MacKinnon, M. McClellan, J. Nichols,

M. Nie, B. Noon, G. Nowacki, K. Petersen, D. Policansky, T. Reimchen,

S. Saunders, J. Schoen, and L. Suring. G. Orians moderated the workshop.

Te workshop was attended by 60 scientists and managers with experience

in forest ecology, conservation biology, and research and management in

the North Pacifc rainforests. We thank all those scientists who partici-

pated in the detailed discussion of each of the eight focal topics. During

the workshop, plans were formalized to use the eight focal topics as the

foundation for a book that would be expanded in scope from the Tongass

figure 0.01. Members of the Tongass science cruise sitting under a nearly 3 m

diam eter Sitka spruce tree (one of the 10 largest known to occur in Alaska) in Tena kee

Inlet on Chichagof Island, May 2008. Left to right, bottom row: Dave Secord, Barry

Noon, John Schoen, Dave Albert. Top row: Andy MacKinnon, Martin Nie, Paul

Alaback, Gordon Orians, Joe Cook, Matt Kirchhof. Photo by John Schoen.

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

Preface aNd ackNoWledgmeNts xi

to include the North Pacifc temperate rainforest from the central British

Columbia coast through southeast Alaska. Special appreciation is extended

to D. Albert and M. Kirchhof, who provided extensive support in plan-

ning, organizing, and participating in both the science cruise and work-

shop. M. Smith assisted with the workshop, and N. Walker prepared

graphics for the book.

Appreciation is extended to D. Albert, G. Fay, M. Hunter, J. Kenagy, J.

Kimmins, M. Kirchhof, M. Nie, B. Noon, P. Paquet, M. Smith, T. Spies,

and F. Swanson for their helpful reviews of individual chapters. D. Della-

Sala and an anonymous reviewer provided invaluable criticisms and edito-

rial suggestions for the entire book.

Audubon Alaska and Te Nature Conservancy provided signifcant

support for the science cruise, workshop, and publication of this book. Te

primary funders of the science cruise and workshop that underpinned this

book were the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; David and Lucile

Packard Foundation; Turner Foundation, Inc.; and Wilburforce Founda-

tion. In addition, the Wilburforce Foundation underwrote a major portion

of the publication costs. Funders of the Audubon and TNC conservation

work in the Tongass National Forest have included (in addition to those

above) the Alaska Conservation Foundation, Brainerd Foundation, Cam-

pion Foundation, ConocoPhillips Alaska, Conservation Alliance, William

and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Leighty Foundation, True North Founda-

tion, and Te Wilderness Society. Classifcation and mapping of terrestrial

ecosystems was supported by a State Wildlife Grant from the Alaska

Department of Fish and Game.

Gordon Orians and John Schoen

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

North Pacific temPerate raiNforests

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

3

1

Introduction

Gordon H. Orians, John W. Schoen,

Jerry F. Franklin, and Andy MacKinnon

the magNificeNt coastal North Pacific temPerate raiNfor-

est, blanketing a glacially carved landscape of precipitous mountains and

dashing rivers, fragmented by thousands of islands, surrounds the eastern

Pacifc Rim from southern Alaska to northern California. Rainforests and

islands have been a major focus of ecological and evolutionary study over

the last century and a half. Today they are a core concern of forest ecolo-

gists, conservation biologists, and others.

Te purpose of this book is to provide a multidisciplinary overview of

key issues related to the management and conservation of the portion of the

coastal North Pacifc rainforests in southeast Alaska and northern coastal

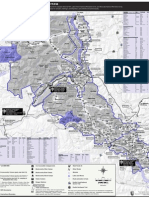

British Columbia. Tis region (fg. 1.01), with its thousands of islands and

millions of hectares of relatively pristine temperate rainforest, is home to

nearly all the species it harbored before people arrived in North America.

It thus provides a valuable opportunity to compare the ecological func-

tioning of a largely intact forest ecosystem with the signifcantly modifed

ecosystems that typify the Earths temperate zone. A broader understand-

ing of the conservation challenges and opportunities that scientists, man-

agers, and conservationists face in this region should be of interest and

value to practitioners seeking to balance economic sustainability with

conservation and ecosystem integrity across the globe.

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

figure 1.01. Te coastal North Pacifc rainforest (shaded area on map) extends

from Yakutat Bay in southeast Alaska to Cape Caution along the central coast of

British Columbia.

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

chaPter 1 5

coastal temPerate raiNforests

are of global imPortaNce

In contrast to the more famous and intensely studied tropical rainfor-

ests, coastal temperate rainforests have never been widespread globally.

Tey constitute only 2% to 3% of the area of the worlds temperate forests.

Coastal temperate rainforests are confned to a handful of relatively small

areas, primarily on the northern Pacifc coast of North America and the

coasts of southern Chile and Argentina, Japan and Korea, and Tasmania

and New Zealand (Alaback 1995; Schoonmaker et al. 1997; DellaSala,

Alaback, et al. 2011). Although temperate rainforests once occurred in

northwestern Europe, most have been eliminated or dramatically altered

by millennia of high-intensity human occupation. Approximately half

of the worlds coastal temperate rainforest is located on the northwest-

ern maritime margin of North America (Ecotrust et al. 1995). DellaSala

(2011) inventoried and described the worlds relatively rare temperate and

boreal rainforests and provided a scientifc catalyst for global and regional

conservation.

Humans did not occupy the cool, coastal temperate rainforests of the

Americas until less than 30,000 years ago. Tese ecosystems were largely

unsuitable for agriculture, so people only lightly modifed them after their

arrival. However, the coastal temperate rainforest of North America south

of Cape Caution on the British Columbia (BC) coast has been extensively

modifed by recent human activities, particularly clear-cut logging and

road construction, sometimes followed by agricultural or urban develop-

ment. Although most of the forests logged in this area have been regener-

ated to younger forests, these younger forests difer strikingly from the

original forests they replaced (Alaback et al., this volume, chapter 4; Per-

son and Brinkman, this volume, chapter 6). Fortunately, large amounts of

the northern half of this forest are similar to what they were when people

arrived in the region about 10,000 years ago, following the Wisconsin gla-

cial period.

Tis area thus ofers unusual opportunities for understanding recent

ecological changes and learning how to develop and apply methods to sus-

tain the ecological processes that yield the goods and services provided by

those ecosystems. In addition, rich opportunities exist to restore the natu-

ral composition, structure, and functioning of portions of these forests that

have been clear-cut and managed as even-aged timber plantations.

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

6 oriaNs, schoeN, fraNkliN, aNd mackiNNoN

Ecological research on the temperate rainforests of the northern Pacifc

coast of North America has greatly increased both scientifc and societal

appreciation of the unusual features and complexity of the regions natural

forest ecosystems, especially its older forests (Franklin et al. 1981). Exten-

sive and important faunal studies, particularly of fagship species such as

the northern spotted owl, marbled murrelet, and Sitka black-tailed deer,

were coupled with ecosystem-level research. Te degree to which tradi-

tional forest practices, which created highly simplifed systems in pursuit

of efcient wood production, have reduced other forest values has been

made clear by other scientifc studies (Puettmann et al. 2009). Te impor-

tance of managed lands (the semi-natural matrix) and limitations of

protected areas as the only focus in conserving biodiversity and critical

eco system processes has also become apparent (Lindenmayer and Frank-

lin 2002; Franklin and Lindenmayer 2009).

Judged on taxonomic uniqueness, unusual ecological or evolutionary

phenomena, and global rarity, coastal temperate rainforests are globally

important ecoregions of the world (Olson and Dinerstein 1998; DellaSala

2011). Te lowland, productive sites are among the terrestrial ecosystems

with the greatest standing biomass. Hence, they may have a signifcant

potential role in future carbon sequestration strategies (Fitzgerald et al.

2011). Even though the forests are dominated by a small number of tree

species, the trees tend to be large, with multiple canopy layers. An abundant

growth of shrubs, herbs, and cryptogams characterizes the understory.

Te biological richness of the forests resides in the forest canopies (arthro-

pods and lichens) and the soils (rich animal and microbial communities).

Coastal temperate rainforests are found in regions that have under gone

extensive climate changes over recent millennia; some were ice covered

during the most recent glacial advances. Tey are expected to experience

sig nifcant climatic changes in the near future as well. Te coastal temper-

ate rainforests of North and South America contain hundreds to thousands

of islands, some of which were connected to the mainland in the recent

past. Tey are still being colonized by new species in response to climate

change and are not currently in species richness equilibrium (Cook and

MacDonald, this volume, chapter 2). Because these forests occur in regions

with high rainfall and complex topography, the interactions between their

terrestrial and marine components are especially complex and important

(Gende et al. 2002; Edwards et al., this volume, chapter 3).

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

chaPter 1 7

the rise of the eNviroNmeNtal scieNces

Life on Earth has survived repeated dramatic changes generated by phys-

ical forces and by life itself. Te productivity and richness of Earths biota

expanded and contracted over the nearly four-billion-year course of lifes

evolution, but the general trend has been an increase in biological diver-

sity. Humans have caused extinctions of species for thousands of years.

When people frst crossed the Bering Land Bridge to North America about

20,000 years ago, they exterminatedpossibly by overhuntingmany

species of a rich fauna of large mammals (Ripple and van Valkenburgh

2010). Extermination of large animals also followed the human coloniza-

tion of Australia. At that time, about 40,000 years ago, Australia had 13

genera of marsupials larger than 50 kg, a genus of gigantic lizards, and a

genus of heavy, fightless birds. All of the species in 13 of those 15 genera

became extinct. When Polynesian people settled in Hawaii about 2,000

years ago, they exterminated at least 39 species of endemic land birds.

More recently European colonists caused the extinction of the Labrador

duck (Comptorhynchus labradorius), great auk (Pinguinus empennis),

Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), and passenger pigeon (Ecto

pistes migratorius), the most abundant land bird in North America when

they arrived.

Although a long-term historical perspective might suggest compla-

cency about current human-caused changes, today the major environmen-

tal changes are being caused by a single species. We are becoming acutely

aware that our eforts to maximize the delivery of a few of the many goods

and services potentially provided by ecosystems (e.g., timber, minerals,

food) has greatly diminished their ability to supply many other goods and

services (e.g., biodiversity conservation, food control, water quality) (Mil-

lennium Ecosystem Assessment 2003).

Eforts to protect Earths rich array of habitats and ecological commu-

nities and to conserve species have a long history. Early conservation

eforts concentrated on species of special economic or social importance,

but gradually, as people became aware of the manifold consequences of the

activities of Earths dramatically increasing human population, the scope

of their research broadened to include habitat destruction and fragmenta-

tion, environmental contamination, spread of diseases, and loss of biodi-

versity. As Earths human population has grown rapidly and individual

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

8 oriaNs, schoeN, fraNkliN, aNd mackiNNoN

wealth has increased substantially in some nations, pressures to extract

goods and services from ecosystems have dramatically increased.

At the same time, we recognize that people have lived in North Pacifc

temperate rainforests for a long timesince at least the last glacial retreat

and continue to live here today. Our aboriginal peoplesgenerally referred

to as First Nations in British Columbia and Alaska Natives in Alaskahave

always had a close relationship with the landscapes they inhabit. But nona-

boriginal residents of this region are also more closely tied to their envi-

ronments than most other North Americans, whether for hunting and

fshing, employment in resource industries, or just generally enjoying their

magnifcent surroundings. Healthy human communities in the North

Pacifc temperate rainforest depend on vibrant ecosystems.

Two developing felds of scientifc inquiryconservation biology and

island biogeographyare particularly relevant to eforts to understand

and manage North Americas coastal temperate rainforests.

Conservation Biology

Te rapid development of the discipline of conservation biology is a

response of the scientifc community and resource professionals to the

accelerating loss of biodiversity. Its practitioners apply principles, data, and

concepts from ecology, biogeography, population genetics, economics,

sociology, anthropology, economics, and philosophy, in an efort to greatly

reduce the current high rates of extinction of species. As the feld devel-

oped, conservation biologists came to realize that concentrating their

eforts on small areas and individual species, although it has conserved

local habitats and ecosystems, has failed to stem the loss of Earths bio-

logical diversity. Tey recognized that they needed to plan and execute

conservation strategies at greater spatial and temporal scales, that is, the

scales at which the ecological and evolutionary processes that generate and

maintain biological diversity operate (Olson and Dinerstein 1998). Conser-

vation biologists have also recognized that management interventions, in

addition to creating reserves, need to incorporate biodiversity concerns in

the semi-natural landscapes that are being managed for commodity pro-

duction (Lindenmayer and Franklin 2002).

Tese insights led to the recognition that large terrestrial areas, char-

acterized by a distinctive climate and dominant vegetation, would be

appropriate management units. Tey need to be large enough to poten-

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

chaPter 1 9

tially maintain viable populations of the species with the largest spatial

requirements, large enough to enable the ecological and evolutionary pro-

cesses that generate and maintain new species to continue, and extensive

enough to include the great variety of Earths habitats and ecological

communities.

Driven in part by the increasing fragmentation of mainland habitats

and the extinctions that it may be contributing to, ecologists and conser-

vation biologists are devoting much attention to extrapolating their

research insights to large spatial and long temporal scales. What processes

become most important at diferent spatial scales? Are diferent scales

nested hierarchically? Which species have the largest area requirements

for long-term persistence of their populations? What new concepts must

be developed for the emerging feld of landscape ecology?

Island Biogeography

Archipelagoes have long played a key role in helping scientists to recog-

nize the importance of long temporal scales and large spatial scales for

the evolution of life and for the structure and functioning of Earths eco-

systems. Insights from the feld of island biogeography, which began with

the pioneering work of Alfred Russel Wallace (1869, 1876, 1880), help us

understand the role of the history of physical changes and movements of

organisms across the landscape in generating the current biota of coastal

North Pacifc temperate rainforests (Cook and MacDonald, this volume,

chapter 2).

For more than 100 years, biogeography was primarily a descriptive feld,

but during the 1960s three major advances changed it into the dynamic

multidisciplinary feld it is today (Brooks 2004). Te frst was the publica-

tion of the equilibrium theory of island biogeography by Robert MacArthur

and Edward O. Wilson (1967). Te second, acceptance of the theory of con-

tinental drift, provided ways to explain many otherwise puzzling patterns

in the distribution of organisms. Te third, the development of phyloge-

netic systematics (Hennig 1966), provided the frst phylogenies that were

rigorously based on quantitative analyses.

Recognition that patches of habitat types on continents resemble

islands in many respects stimulated the use of concepts of island biogeog-

raphy to explore the dynamics of species on mainland virtual islands.

One result has been the development of hypotheses of nonequilibrium

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

10 oriaNs, schoeN, fraNkliN, aNd mackiNNoN

island biogeography, the investigation of patterns of faunal relaxation on

recently isolated habitats. Low mammal species richness in montane habi-

tats in the Great Basin of North America (Brown 1971) and in the tropical

rainforests of northern Queensland, Australia (Moritz 2005), are prime

examples of nonequilibrium island biogeographic patterns.

As a consequence of dramatic sea level changes that accompanied the

expansion and contraction of Pleistocene glaciers, many areas of the

coastal temperate rainforests of North America that were formerly con-

nected to the mainland have recently become islands. Studies of organisms

on some of those islands, in Barkley Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver

Island (Cody 2006), for example, have yielded important insights into

foral relaxation. Te biota of the coastal rainforests of North America is

defnitely not currently in equilibrium.

maNagemeNt challeNges

of the tWeNty-first ceNtury

One of the primary challenges facing residents of coastal North Pacifc

temperate rainforests as we enter the twenty-frst century is how to redesign

our land allocation and management strategies to address the goals of main-

taining vibrant and dynamic ecosystems and healthy human communities.

Tere are numerous examples around the world (and farther south on our

coast) where the ability of ecosystems to sustainably provide the full array

of goods and services has been seriously compromised by resource devel-

opment. Because of the largely undeveloped nature of North Pacifc coastal

landscapesan increasingly rare commodity globallywe have an oppor-

tunity to work diligently to better understand the complex interrelation-

ships among the diferent types of goods and services these ecosystems

provide so that we can obtain some valuable resources (e.g., forest products)

without diminishing other services (e.g., water quality, biodiversity).

To achieve these goals, it would be helpful to focus on ecosystems and

not on political boundaries. Te ecosystems and species in our region dont

recognize the BCAlaska international border. Yet almost every inventory

and mapping efort, and every management plan, has that border as its

southern boundary (for Alaskan plans) or its northern boundary (for BC

plans). Tere is little coordination in things like protected areas planning

between BC and Alaska. If we want to properly protect this area, there

must be.

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

chaPter 1 11

Another border that needs bridging is the one between terrestrial, fresh-

water, and marine realms. Tere are few places on earth where marine and

terrestrial realms are so closely linked as in coastal temperate rainforests.

Yet terrestrial and marine managers generally work for diferent agencies

and conduct their research, inventory, and planning in isolation from each

other. Although this book is primarily about managing terrestrial and fresh-

water realms, many of the ideas and recommendations it contains must be

implemented in cooperation with marine scientists and managers.

On the Canadian side of the border, almost all (>95%) of the land is

Provincial Crown land (owned by the province). (Land claims negotiations

currently underway with a number of coastal First Nations will likely

result in considerable amounts of this land being transferred to First

Nations ownership.) Land use plans were developed for BCs central and

northern coast in 2006, and in Haida Gwaii in 2010. Tese plans designate

approximately one-third of the central and northern BC coast, and one-

half of Haida Gwaii, as protected areas and set out management practices

for the rest of the landscape.

In southeast Alaska, about 90% of the land area is federal land. Te Ton-

gass National Forestat 6.8 million haencompasses nearly 80% of the

land area; Glacier Bay National Park covers 12% of the region. Te rest of

the land base is managed primarily by the state of Alaska and private land

holders including Native corporations. Te Tongass Land and Resource

Management Plan (USDA Forest Service 2008a) is the guiding document

for most of the lands of southeast Alaska.

Te objectives, profession, and practice of forestry, the most important

modifers of North Americas coastal temperate rainforests, have under-

gone major changes during the last 30 years as a consequence of funda-

mental changes in societal perceptions, the domestic and global wood

products industry, and scientifc understanding of forest ecosystems and

landscapes. Changes continue to be driven by new public priorities, new

scientifc information, and changing economic conditions, combined with

the recognition that we need to, and can, learn from past mistakes.

New Priorities

Since its origin, the profession of forestry focused on the efcient and

sustainable production of timber (Puettmann et al. 2009), frmly grounded

in tenets that explicitly considered wood to be the most important product

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

12 oriaNs, schoeN, fraNkliN, aNd mackiNNoN

of forests. Broader perspectives on the value of forests began to emerge in

the 1960s with increased societal awareness and concern for the environ-

ment. Tis was expressed by adoption of many signifcant environmental

laws during the 1960s and 1970s, several of which had profound conse-

quences for the management of public forest lands. Examples include the

Wilderness Act of 1964, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969,

the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and the National Forest Management

Act of 1976 in the United States; and the Canadian Forestry Act (1985), the

Canadian Environmental Protection Act (1999), and the Federal Fisheries

Act of Canada (1985). One major diference between the two countries is

that Canada did not introduce federal legislation to protect endangered

species until 2002 (Species at Risk Act). In both countries, these laws and

regulations refected societys increased environmental concerns.

New Science

Signifcant advances in scientifc understanding of forest ecosystems and

landscapes developed in parallel with societal awakening regarding the

environment; in fact, scientifc studies made a signifcant contribution to

the shift in societal interest in the environment. Most previous forest

research had focused on regeneration and growth of commercial tree spe-

cies and on silvicultural practices that optimized the production of wood

(Puettmann et al. 2009). In the 1960s, research was initiated on forests as

ecosystems; this research received a signifcant boost with the US Inter-

national Biological Program in 1968, which was followed by establishment

of an ecosystem studies program in the National Science Foundation

(1973). Te US Forest Service research program contributed signifcantly

to many of these projects. In BC, formal independent science panels were

established to guide development of land use plans for Clayoquot Sound

(southwestern Vancouver Island; Scientifc Panel for Sustainable Forest

Practices in Clayoquot Sound 1995), and the central and northern coast and

Haida Gwaii (e.g., Coast Information Team 2004).

Te combination of environmental legislation and research had signif-

cant impacts on forest management on all forest lands, public and private.

Tese efects were applied diferently in the United Stateswhere coastal

temperate rainforests are held by a combination of federal and state gov-

ernments and private entitiesthan in British Columbia, where forest

lands are almost entirely owned by the provincial government. In the US,

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

chaPter 1 13

the laws and regulations were particularly profound on federal forests

where the environmental obligations were both most extensive and clearly

defned. In BC, the important legislation governing forest practices is pro-

vincial legislation, such as the Forest and Range Practices Act (2002). In

both countries, this combination of environmental legislation and research

represented an immense challenge to the forestry professionboth to

their fundamental tenets and to traditional silvicultural practices. Ulti-

mately they required the development of a new paradigm based upon

modern ecosystem science, including the complex and profound roles of

natural disturbances (Franklin et al. 2007; North and Keeton 2008).

New Economics

Globalization of the wood products industry late in the twentieth century

brought yet another challenge to forestry in North America. With global-

ization of trade in wood products and of capital markets, corporations

moved to invest in areas where economic production was most efcient

primarily in forested regions in the southern hemisphere (Franklin and

Johnson 2004). Development of fber farmsshort rotation plantations of

exotic pines and eucalyptswas clearly an economically superior approach

for growing the large volumes of wood needed to feed the global markets

for common wood-based products. Investments fowed to New Zealand,

Chile, and Australia. In southeast Alaska and northern coastal BC, the

timber industry will increasingly be at a competitive disadvantage with

more productive, less isolated forested areas in the production and milling

of large volumes of commodity lumber or pulp.

Today society increasingly values forest ecosystems for the broad

variety of services and goods that they provide, including watershed pro-

tection, carbon sequestration, habitat for a large array of organisms, and

recreation and inspiration as well as wood. Currently, the provision of a

well-regulated fow of high-quality water may be the most highly valued

service provided by undisturbed forest ecosystems. Given the surfeit of

efciently produced wood available from tree plantations, timber produc-

tion from older forests in North America is declining in value. However,

forests may have continued signifcance for local communities as sources

of raw materials.

Te challenges these social, environmental, and economic changes

pose for forest management in the next century are immense. Goals that

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

14 oriaNs, schoeN, fraNkliN, aNd mackiNNoN

give primacy to efcient production of wood are no longer viable. Rather,

management approaches that seek to restore and sustain complex forest

ecosystems and the full array of goods, services, and organisms they pro-

vide are required. Fortunately, the substantial scientifc information that

has accumulated during the last several decades provides tools for helping

meet this goal. Unfortunately, the profession has only recently incorpo-

rated such science into management philosophies and practices (Franklin

et al. 2007; Puettman et al. 2009; Bunnell and Dunsworth 2009).

Changes in the economics of the forest industry, however, create sig-

nifcant difculties as well as conservation opportunities. Although the

reduction in the large-scale extraction industry from large regions in

North America lessens pressures for timber harvest, it also leaves areas

without skilled workers needed to carry out forest stewardship and with-

out processing facilities that can help subsidize the restoration and other

forest management activities that need to be undertaken. Tis lack of

skilled professionals is of concern because society is unlikely to expend

large amounts of money for forest restoration and stewardship. Climate

change adds another dimension of uncertainty that society and profes-

sional resource managers must deal with. Managing to maintain future

options and ecological resiliency have become important elements in nat-

ural resource management.

oPPortuNities aNd challeNges WithiN coastal

North Pacific temPerate raiNforests

New World coastal temperate rainforests ofer unusual opportunities for

people to apply the latest concepts developed by researchers in the envi-

ronmental sciences at an ecoregion scale. Tis knowledge can guide eforts

to plan for long-term ecological integrity and sustainable use of these

mostly intact native forest ecosystems. A signifcant body of information

exists upon which to base future research, restoration, and management

strategies. Information on the rainforests of the North Pacifc coast of

North America has been summarized by Ecotrust et al. (1995) and Della-

Sala, Moola, et al. (2011). Alaback (1991) and Tecklin et al. (2011) detailed

the rainforests of Chile and Argentina.

Recognizing the potential for innovative conservation strategies in the

cool temperate rainforests of North America, scientists with Audubon

Alaska (AA) and Te Nature Conservancy, Alaska (TNC), carried out an

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

chaPter 1 15

intensive analysis of the composition and distribution of biological

resources in southeast Alaska (Albert and Schoen 2007a, 2007b; Schoen

and Albert 2007). In May 2008, AA and TNC hosted a visit by eight scien-

tists who assessed the analysis, observed the array of natural vegetation

types in the area, and viewed the efects of commercial timber harvests on

aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Te consensus of the group was that a

continuation of past management practices would likely have signifcant

adverse efects on regional biodiversity and that further in-depth discus-

sions and analyses would be useful to inform management decisions.

Tis book is a product of that efort. Building upon the extensive back-

ground provided by ecological research in the region, we focus on the data

and insights derived from recent research in the coastal rainforests of

British Columbia and Alaska. Tis body of work will help inform eforts

to develop and implement efective management strategies for these rain-

forests. Many compelling issues are associated with the ecology and con-

servation of the North Pacifc temperate rainforest. In selecting the scope

of this book and choosing the topics for its eight papers, we carefully con-

sidered what constitutes the fundamental ecological processes and human

behaviors that drive the dynamic behavior of this forest and how managers

can use this information to make decisions that will result in sustainable

ecosystems and human communities. Authors of the chapters demon-

strate how cutting edge concepts in ecology, biogeography, and conserva-

tion biology are informing, and can continue to inform, management

actions on the ground.

To understand why an ecosystem has its current properties, one needs

to know something of its history. Terefore we devote the frst portion of

the book to chapters that explore the current functioning of the regions

ecosystems and describe how they have been infuenced by the regions

recent history. An overview of the regions biogeographic history was

needed to set the stage for understanding the current biota and how it got

there. Accordingly, the second chapter, Island Life: Coming to Grips with

the Insular Nature of Southeast Alaska and Adjoining Coastal British

Columbia, by Joe Cook and Stephen MacDonald, describes how the

advances and retreats of glaciers, major changes in sea levels, and complex

patterns of recolonization by plants and animals following the last glacial

retreat have yielded what we see today.

Te ecological dynamics of the region are driven by its rugged topog-

raphy and high rainfall. Te third chapter, Riparian Ecology, Climate

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

16 oriaNs, schoeN, fraNkliN, aNd mackiNNoN

Change, and Management in North Pacifc Coastal Rainforests, by Rick

Edwards, Dave DAmore, Erik Norberg, and Frances Biles, was commis-

sioned to describe the dominant features of this dynamic landscape, how

they have changed, and to explore their ecological consequences. A major

feature of the region is that its rivers discharge great amounts of sediments

and nutrients to adjacent waters. Conversely, salmon carry large amounts

of nutrients upriver, where they feed a variety of animals and enrich veg-

etation near the rivers. Understanding these massive nutrient inter-

changes, which are more powerful in this region than elsewhere on Earth,

is of vital importance for managing these systems.

Not surprisingly, disturbances of varying intensity and frequency

occur in this rugged landscape. Terefore, we commissioned a chapter

dealing with the nature and consequences of the current and historically

recent patterns caused by windstorms, fre, pest outbreaks, landslides,

and other disturbances that frequent the region. In chapter 4, Natural

Disturbance Patterns in the Temperate Rainforests of Southeast Alaska

and Adjacent British Columbia, Paul Alaback, Gregory Nowacki, and Sari

Saunders analyze these disturbances and describe the complex mosaic of

plant communities that they create in space and time. Te requirements

of many of the regions species have evolved in response to those condi-

tions. Many species may not persist in the region without the full variety

of existing habitat types.

We commissioned the chapters for the next part of the book to explore

how humans have interacted with and changed the regions rainforests.

Te current patterns of disturbance generated by human activity difer in

some important ways from historical patterns. To understand how and

why humans use the region today, and to provide information to guide

future human use of the regions natural resources, we need to know the

history of human occupation and use.

Chapter 5, Indigenous and Commercial Uses of the Natural Resources

of the North Pacifc Rainforest with a Focus on Southeast Alaska and

Haida Gwaii, by Lisa Crone and Joe Mehrkens, describes how the frst

humans to arrive in the region used its resources and how the commercial

use of the regions forest, which began seriously only during the twentieth

century, has left a legacy of highly modifed habitats. It also explores how

understanding the policies that supported those activities and their eco-

nomic and social legacies can help guide a transition to a diferent and

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

chaPter 1 17

more sustainable use of the regions natural resources and yield conditions

that support rich and rewarding human lives.

Constructing roads to enable a regions resources to be accessed, har-

vested, and exported is a dominant component of modern exploitation of

natural environments. Terefore, we judged that a chapter that explored

the direct and indirect consequences of road building and timber harvest-

ing would be an essential component of our analysis. Chapter 6, Succes-

sion Debt and Roads: Short- and Long-Term Efects of Timber Harvest on

a Large-Mammal Predator-Prey Community in Southeast Alaska, by Dave

Person and Todd Brinkman, explores those issues and also explains how

transitioning from old growth to second growth afects forest habitats. Te

unique legacy of road-building eforts in North Pacifc rainforests is also

discussed in this chapter.

Te rapidly expanding feld of conservation biology, an applied science

that uses theories and data from a broad range of disciplines to conserve,

maintain, and restore the biological diversity and resilience of ecosystems,

provides a rich array of concepts and tools for managers. Chapter 7, Con-

cepts of Conservation Biology Applied to Wildlife in Old-Forest Ecosys-

tems, with Special Reference to Southeast Alaska and Northern Coastal

British Columbia, by Bruce Marcot, describes how these concepts and

tools have been used and can be used in the future to creatively address

the complex issues that confront todays managers.

Watersheds have been proposed and widely used as units to guide

thinking about managing landscapes. However, an in-depth analysis of

when and how to use watersheds as management units had not been con-

ducted. Terefore we commissioned chapter 8, Why Watersheds: Evaluat-

ing the Protection of Undeveloped Watersheds as a Conservation Strategy

in Northwestern North America, in which Ken Lertzman and Andy

MacKinnon describe the advantages and disadvantages of using water-

sheds as planning units. Tey also show under which conditions the

advantages of using watersheds are likely to outweigh the disadvantages,

and vice versa. Teir insightful analyses should be of value to managers

operating in a wide variety of ecosystems.

Given that timber harvest has been the most important modifer of

North Pacifc rainforests, we decided that learning from past and current

eforts to manage those forests to maintain the full array of ecosystem

goods and services could help forest managers in this and other forest

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

18 oriaNs, schoeN, fraNkliN, aNd mackiNNoN

ecosystems. Terefore we commissioned a chapter that would describe the

experiences of forest managers with alternative harvesting techniques in

the coastal rainforests and their efects on forest succession and biodiver-

sity conservation. Chapter 9, Variable Retention Harvesting in North

Pacifc Temperate Rainforests, by Bill Beese, performs that vital service.

Te book would not be complete without a fnal Synthesis (chapter 10)

that brings together and interprets the general perspectives that emerge

from the previous chapters (importance of historical perspectives at mul-

tiple scales, importance of variability, virtual versus real islands, impor-

tance of clearly specifying conservation and management goals, when and

why should we try to mimic nature, etc.). Te synthesis also shows how

attempts to apply general theories from the environmental sciences have

led to useful, rational, and justifable recommendations for modifying

management and conservation strategies in the region. It emphasizes how

opportunities and challenges can be used to conserve biological diversity

and ecological integrity while also sustaining local economies and quality

of human life, both in the region and elsewhere. Although we know a great

deal about North Pacifc temperate rainforest ecosystems, important gaps

in knowledge remain. Te concluding chapter highlights uncertainties in

our understanding and suggests how these uncertainties might be reduced.

Although this book concentrates on research and its management

implications in a specifc region, the insights gained from experiences in

North Pacifc rainforests should be useful to researchers and managers in

other temperate rainforests, as well as in other places where the composi-

tion, structure, and functioning of natural ecosystems is being modifed

by human endeavors. Unlike many regions of the world, the northern por-

tion of the coastal North Pacifc temperate rainforest provides unusual

opportunities for studying processes and management alternatives in both

modifed and unmodifed ecosystems. Researchers and managers in other

regions, particularly in forest and island ecosystems, should gain from

reading about the experiences of scientists and managers in North Pacifc

rainforests. Both the forests themselves and the quality of life experienced

by people living there will beneft from such eforts.

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

O

F

W

A

S

H

I

N

G

T

O

N

P

R

E

S

S

You might also like

- Ecological Restoration of Southwestern Ponderosa Pine ForestsFrom EverandEcological Restoration of Southwestern Ponderosa Pine ForestsNo ratings yet

- Kakadu RegionDocument209 pagesKakadu RegionD.s.LNo ratings yet

- The Race to Save the World's Rarest Bird: The Discovery and Death of the Po'ouliFrom EverandThe Race to Save the World's Rarest Bird: The Discovery and Death of the Po'ouliNo ratings yet

- (2005) Tropical Forests of The Guiana Shield Ancient Forests in A Modern World PDFDocument541 pages(2005) Tropical Forests of The Guiana Shield Ancient Forests in A Modern World PDFBruna BritoNo ratings yet

- The Forest Landscape Restoration Handbook (Earthscan Forestry Library) (PDFDrive) PDFDocument190 pagesThe Forest Landscape Restoration Handbook (Earthscan Forestry Library) (PDFDrive) PDFJmp JmpNo ratings yet

- Birds of the Great Basin: A Natural HistoryFrom EverandBirds of the Great Basin: A Natural HistoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- FS0106 - Trail Bike Riding Strathbogie State ForestDocument3 pagesFS0106 - Trail Bike Riding Strathbogie State ForesthullsamNo ratings yet

- Vegetation of Australian Riverine Landscapes: Biology, Ecology and ManagementFrom EverandVegetation of Australian Riverine Landscapes: Biology, Ecology and ManagementNo ratings yet

- Global Survey of Ex Situ Conifer CollectionsDocument50 pagesGlobal Survey of Ex Situ Conifer CollectionsChromaticghost2No ratings yet

- A Chorus of Cranes: The Cranes of North America and the WorldFrom EverandA Chorus of Cranes: The Cranes of North America and the WorldNo ratings yet

- 4th Mountain Lion Workshop.1991Document120 pages4th Mountain Lion Workshop.1991Lucía SolerNo ratings yet

- Heterocera of Papua, Christophe Avon 2014Document208 pagesHeterocera of Papua, Christophe Avon 2014Christophe Avon100% (1)

- Advances in Reintroduction Biology of Australian and New Zealand FaunaFrom EverandAdvances in Reintroduction Biology of Australian and New Zealand FaunaNo ratings yet

- Hannah's Temperate Broadleaf Forest BrochureDocument2 pagesHannah's Temperate Broadleaf Forest BrochureCharles IppolitoNo ratings yet

- An Elementary Manual of New Zealand Entomology: Being an Introduction to the Study of Our Native InsectsFrom EverandAn Elementary Manual of New Zealand Entomology: Being an Introduction to the Study of Our Native InsectsNo ratings yet

- Forest Restoration in LandscapesDocument440 pagesForest Restoration in Landscapesleguim6No ratings yet

- The Great Basin Seafloor: Exploring the Ancient Oceans of the Desert WestFrom EverandThe Great Basin Seafloor: Exploring the Ancient Oceans of the Desert WestNo ratings yet

- Whales Without WallsDocument19 pagesWhales Without WallsRahul NandaNo ratings yet

- A Natural History of Australian Bats: Working the Night ShiftFrom EverandA Natural History of Australian Bats: Working the Night ShiftRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Antarctic Marine Biology PrimerDocument7 pagesAntarctic Marine Biology PrimerValentina Sandoval ParraNo ratings yet

- Wilderness North CascadesDocument1 pageWilderness North CascadesHolly TjadenNo ratings yet

- The Terrestrial Protected Areas of Madagascar: Their History, Description, and Biota, Volume 3: Western and southwestern Madagascar - SynthesisFrom EverandThe Terrestrial Protected Areas of Madagascar: Their History, Description, and Biota, Volume 3: Western and southwestern Madagascar - SynthesisNo ratings yet

- Minnesota DNR Shallow Lakes PlanDocument56 pagesMinnesota DNR Shallow Lakes Plandave1132No ratings yet

- Fiona's Great Barrier Reef Travel BrochureDocument5 pagesFiona's Great Barrier Reef Travel BrochureCharles Ippolito100% (1)

- Tracks and Shadows: Field Biology as ArtFrom EverandTracks and Shadows: Field Biology as ArtRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Guides To The Freshwater Invertebrates of Southern Africa Volume 5 - Non-ArthropodsDocument304 pagesGuides To The Freshwater Invertebrates of Southern Africa Volume 5 - Non-ArthropodsdaggaboomNo ratings yet

- The Fragmented Forest: Island Biogeography Theory and the Preservation of Biotic DiversityFrom EverandThe Fragmented Forest: Island Biogeography Theory and the Preservation of Biotic DiversityNo ratings yet

- Cordillera Cóndor Ecuador-Peru Jan-1997 PDFDocument234 pagesCordillera Cóndor Ecuador-Peru Jan-1997 PDFJosé Luis Espinoza AmiNo ratings yet

- Checklist of Vascular Plants of The Southern Rocky Mountain RegionDocument316 pagesChecklist of Vascular Plants of The Southern Rocky Mountain Regionfriends of the Native Plant Society of New MexicoNo ratings yet

- Great Florida Birding Trail Map - Panhandle SectionDocument28 pagesGreat Florida Birding Trail Map - Panhandle SectionFloridaBirdingTrailNo ratings yet

- Pollination of AdromischusDocument2 pagesPollination of AdromischusveldfloraedNo ratings yet

- Syesis: Vol. 8, Supplement 1: Vegetation and Environment of the Coastal Western Hemlock Zone in Strathcona Provincial Park, British Columbia, CanadaFrom EverandSyesis: Vol. 8, Supplement 1: Vegetation and Environment of the Coastal Western Hemlock Zone in Strathcona Provincial Park, British Columbia, CanadaNo ratings yet

- Ecosistemas de Puerto RicoDocument444 pagesEcosistemas de Puerto RicoPebbles42No ratings yet

- Bark Beetle Management, Ecology, and Climate ChangeFrom EverandBark Beetle Management, Ecology, and Climate ChangeKamal J.K. GandhiNo ratings yet

- A Review of Freshwater Ecosystems in The Northern CapeDocument34 pagesA Review of Freshwater Ecosystems in The Northern CaperamolloppNo ratings yet

- Wonders of Sand and Stone: A History of Utah's National Parks and MonumentsFrom EverandWonders of Sand and Stone: A History of Utah's National Parks and MonumentsNo ratings yet

- South Australian Offshore Islands - DeNRDocument554 pagesSouth Australian Offshore Islands - DeNRMark GrebeNo ratings yet

- AVES de La Reserva PacayaDocument61 pagesAVES de La Reserva PacayaGianina J. Mundo PadillaNo ratings yet

- Seafloor Geomorphology as Benthic Habitat: GeoHab Atlas of Seafloor Geomorphic Features and Benthic HabitatsFrom EverandSeafloor Geomorphology as Benthic Habitat: GeoHab Atlas of Seafloor Geomorphic Features and Benthic HabitatsNo ratings yet

- Zoogeographic Regions MapDocument122 pagesZoogeographic Regions MapEldimson Bermudo100% (3)

- Gastropods: Technical Terms and MeasurementsDocument4 pagesGastropods: Technical Terms and MeasurementsBudi AfriyansyahNo ratings yet

- More Tree Talk: The People, Politics, and Economics of TimberFrom EverandMore Tree Talk: The People, Politics, and Economics of TimberRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Old World Fruit BatsDocument263 pagesOld World Fruit BatsAnonymous HXLczq3No ratings yet

- Desert Biology: Special Topics on the Physical and Biological Aspects of Arid RegionsFrom EverandDesert Biology: Special Topics on the Physical and Biological Aspects of Arid RegionsG. W. BrownNo ratings yet

- IUCN Manual Invasive SpeciesDocument240 pagesIUCN Manual Invasive SpeciesTorukMacto18No ratings yet

- Camera Hunter: George Shiras III and the Birth of Wildlife PhotographyFrom EverandCamera Hunter: George Shiras III and the Birth of Wildlife PhotographyNo ratings yet

- Gunther Kunkel (Auth.) Flowering Trees in Subtropical Gardens 1978Document342 pagesGunther Kunkel (Auth.) Flowering Trees in Subtropical Gardens 1978Ignacio Garcia Ruiz100% (1)

- 1996 Thewissen Madar Hussain AmbulocetusDocument94 pages1996 Thewissen Madar Hussain AmbulocetusMARIA TAPIA DE LA JARANo ratings yet

- AB-WA-2013 WA Australasian Bittern Project Report PDFDocument122 pagesAB-WA-2013 WA Australasian Bittern Project Report PDFEguene SofteNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of the 18th International Sea Turtle SymposiumDocument316 pagesProceedings of the 18th International Sea Turtle SymposiumAreia Ortiz SarabiaNo ratings yet

- Crookes Valley Park - Masterplan-Ponderosa - Philadelphia GreenspaceDocument195 pagesCrookes Valley Park - Masterplan-Ponderosa - Philadelphia Greenspace焚烛No ratings yet

- Racial EcologiesDocument26 pagesRacial EcologiesUniversity of Washington Press100% (1)

- Woke Gaming: Digital Challenges To Oppression and Social InjusticeDocument38 pagesWoke Gaming: Digital Challenges To Oppression and Social InjusticeUniversity of Washington Press40% (5)

- Building Reuse: Building Reuse Sustainability, Preservation, and The Value of DesignDocument23 pagesBuilding Reuse: Building Reuse Sustainability, Preservation, and The Value of DesignUniversity of Washington Press67% (3)

- Sexuality in ChinaDocument21 pagesSexuality in ChinaUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Environmental Justice in Postwar America: A Documentary ReaderDocument37 pagesEnvironmental Justice in Postwar America: A Documentary ReaderUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Shanghai SacredDocument32 pagesShanghai SacredUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Family History of Illness: Memory As MedicineDocument27 pagesFamily History of Illness: Memory As MedicineUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Asian American Feminisms and Women of Color PoliticsDocument9 pagesAsian American Feminisms and Women of Color PoliticsUniversity of Washington Press0% (1)

- Gender Before Birth: Sex Selection in A Transnational ContextDocument46 pagesGender Before Birth: Sex Selection in A Transnational ContextUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Molecular Feminisms: Biology, Becomings, and Life in The LabDocument49 pagesMolecular Feminisms: Biology, Becomings, and Life in The LabUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Gender and Chinese HistoryDocument25 pagesGender and Chinese HistoryUniversity of Washington Press0% (1)

- John OkadaDocument19 pagesJohn OkadaUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Environmental Justice in Postwar AmericaDocument37 pagesEnvironmental Justice in Postwar AmericaUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Transforming PatriarchyDocument47 pagesTransforming PatriarchyUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Power in The Telling: Grand Ronde, Warm Springs, and Intertribal Relations in The Casino EraDocument19 pagesPower in The Telling: Grand Ronde, Warm Springs, and Intertribal Relations in The Casino EraUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Making Climate ChangeDocument36 pagesMaking Climate ChangeUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- We Are Dancing For You: Native Feminisms and The Revitalization of Women's Coming-of-Age CeremoniesDocument44 pagesWe Are Dancing For You: Native Feminisms and The Revitalization of Women's Coming-of-Age CeremoniesUniversity of Washington Press100% (2)

- Nuclear ReactionsDocument41 pagesNuclear ReactionsUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Making New Nepal: From Student Activism To Mainstream PoliticsDocument48 pagesMaking New Nepal: From Student Activism To Mainstream PoliticsUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Medicine and Memory in Tibet: Amchi Physicians in An Age of ReformDocument47 pagesMedicine and Memory in Tibet: Amchi Physicians in An Age of ReformUniversity of Washington Press100% (1)

- Olympic National ParkDocument3 pagesOlympic National ParkUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- High-Tech HousewivesDocument26 pagesHigh-Tech HousewivesUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Before YellowstoneDocument13 pagesBefore YellowstoneUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Cultivating NatureDocument44 pagesCultivating NatureUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- The Organic ProfitDocument33 pagesThe Organic ProfitUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Firebrand FeminismDocument46 pagesFirebrand FeminismUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- A Family History of IllnessDocument25 pagesA Family History of IllnessUniversity of Washington Press100% (1)

- Bringing Whales AshoreDocument43 pagesBringing Whales AshoreUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Organic SovereigntiesDocument43 pagesOrganic SovereigntiesUniversity of Washington Press100% (1)

- Gender Before BirthDocument46 pagesGender Before BirthUniversity of Washington PressNo ratings yet

- Identification Study and Mechanical Characterization Clay Stabilized by GumarabicseyalDocument9 pagesIdentification Study and Mechanical Characterization Clay Stabilized by GumarabicseyalIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Explore Yoho National Park's Scenic Lake O'Hara TrailsDocument1 pageExplore Yoho National Park's Scenic Lake O'Hara TrailsMihaela CazacuNo ratings yet

- Forms of Condensation & Precipitation ExplainedDocument84 pagesForms of Condensation & Precipitation ExplainedAmitaf Ed OrtsacNo ratings yet

- Physical Geography EssayDocument7 pagesPhysical Geography EssayKieran KingNo ratings yet

- Akil PrasathDocument3 pagesAkil Prasathapi-655209070No ratings yet

- Environmental Impact Ent Report Scoping Report: Silver Hill Duck July 2020Document27 pagesEnvironmental Impact Ent Report Scoping Report: Silver Hill Duck July 2020Sadiq AhmadNo ratings yet

- 5.4 What Are The Causes and Effects of Landslides AnswerDocument19 pages5.4 What Are The Causes and Effects of Landslides AnswerYannie SoonNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Benefits and Environmental Risks of Soil Fertiliz Using DigestateDocument21 pagesAgricultural Benefits and Environmental Risks of Soil Fertiliz Using Digestatetiti neamtuNo ratings yet

- Air Modelling ReportDocument8 pagesAir Modelling ReportadiNo ratings yet

- Fossil Evidence for Continental DriftDocument13 pagesFossil Evidence for Continental Driftjennelyn losantaNo ratings yet

- Illustrated Guide To Soil TaxonomyDocument552 pagesIllustrated Guide To Soil Taxonomyemdaynuh100% (1)

- RISHABH YADAV - Chemistry ProjectDocument22 pagesRISHABH YADAV - Chemistry ProjectRISHABH YADAVNo ratings yet

- FREE eBook for ECGC PO Practice QuestionsDocument24 pagesFREE eBook for ECGC PO Practice QuestionsAdithya BallalNo ratings yet

- CV Guilherme CorteDocument7 pagesCV Guilherme Corteapi-680942637No ratings yet

- River Valley Project Planning TermsDocument30 pagesRiver Valley Project Planning TermsGREYHOUND ENGINEERS INDIA INDIA PVT.LTDNo ratings yet

- Consolidation TestDocument16 pagesConsolidation Test1man1bookNo ratings yet

- Ground Improvement TechniquesDocument14 pagesGround Improvement Techniqueskrunalshah1987No ratings yet

- Appropriate Technologies For Rural Development by Use of Soil Conservation and Waste Land DevelopmentDocument20 pagesAppropriate Technologies For Rural Development by Use of Soil Conservation and Waste Land DevelopmentBhuvanesh InderkumarNo ratings yet

- Oyarzún PDFDocument5 pagesOyarzún PDFJessica Mho100% (1)

- Flood Preparation and Mitigation in Barangay Cabayaoasan Bugallon PangasinanDocument65 pagesFlood Preparation and Mitigation in Barangay Cabayaoasan Bugallon Pangasinanjames0% (1)

- CIDAM Template Earth Science Group 1Document12 pagesCIDAM Template Earth Science Group 1Sheirmay Antonio CupatanNo ratings yet

- Provas de Proficiencia Ingles 1Document10 pagesProvas de Proficiencia Ingles 1Daniel AguiarNo ratings yet

- Subodh BookDocument9 pagesSubodh BookEasteak AhamedNo ratings yet

- CH 13 NcertDocument7 pagesCH 13 NcertSaumya BhartiNo ratings yet

- Learn The Differences BetweenDocument2 pagesLearn The Differences BetweenPrakash VankaNo ratings yet

- Building MaterialDocument15 pagesBuilding MaterialSonya BhartiNo ratings yet

- 2010asu2 PDFDocument156 pages2010asu2 PDFAlif Muhammad FadliNo ratings yet

- 1-Edades Caztor Troy v. - q1 Hba w3&4 Task No.1Document3 pages1-Edades Caztor Troy v. - q1 Hba w3&4 Task No.1Jepoy dizon Ng Tondo Revengerz gangNo ratings yet

- Agriculture Ecosystems and EnvironmentDocument10 pagesAgriculture Ecosystems and EnvironmentOmar Condori ChoquehuancaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 ExcerciseDocument12 pagesChapter 2 ExcerciseÅdän Ahmĕd DâkañeNo ratings yet

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (811)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (33)

- Smokejumper: A Memoir by One of America's Most Select Airborne FirefightersFrom EverandSmokejumper: A Memoir by One of America's Most Select Airborne FirefightersNo ratings yet

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseFrom EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (69)

- The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorFrom EverandThe Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (137)

- The Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterFrom EverandThe Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterNo ratings yet

- The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildFrom EverandThe Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (44)

- Lessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse”From EverandLessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse”Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Chesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier IslandFrom EverandChesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier IslandRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (38)

- Water to the Angels: William Mulholland, His Monumental Aqueduct, and the Rise of Los AngelesFrom EverandWater to the Angels: William Mulholland, His Monumental Aqueduct, and the Rise of Los AngelesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (21)

- Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldFrom EverandWayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- The Weather Machine: A Journey Inside the ForecastFrom EverandThe Weather Machine: A Journey Inside the ForecastRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (31)

- The Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanFrom EverandThe Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanNo ratings yet

- Why Fish Don't Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of LifeFrom EverandWhy Fish Don't Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (699)

- A Brief History of the Earth's Climate: Everyone's Guide to the Science of Climate ChangeFrom EverandA Brief History of the Earth's Climate: Everyone's Guide to the Science of Climate ChangeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal IntelligenceFrom EverandThe Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal IntelligenceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Eels: An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World's Most Mysterious FishFrom EverandEels: An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World's Most Mysterious FishRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (30)

- World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other AstonishmentsFrom EverandWorld of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other AstonishmentsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (221)

- The Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsFrom EverandThe Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (63)