Professional Documents

Culture Documents

For Justice Concerns Us All

Uploaded by

Saurav DattaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

For Justice Concerns Us All

Uploaded by

Saurav DattaCopyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIALS

For Justice Concerns Us All

We need a public debate on guidelines for appointing senior members of the judiciary.

he appointment and transfer of judges to the countrys high courts and the Supreme Court have been a contentious issue. It has simmered for many years between the higher judiciary and the government and ares up at periodic intervals. In April this year, the union law minister announced that a Judicial Appointments Commission to give the executive a voice in the appointments was on the cards. To this the then Chief Justice of India (CJI) Altamas Kabir responded that the collegium system was working ne and there was no need to change it. Soon after taking ofce, the new CJI P Sathasivam also reiterated his faith in the collegium system. The collegium, comprising four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court and the CJI, decides on transfers and appointments. It has been in existence for nearly 20 years now and was established in response to two signicant rulings of the Supreme Court. Its critics point out that it is not sanctioned by the Constitution which states that the appointments should be made by the president after consulting whichever judges of the high courts and the Supreme Court (including the CJI) he/she deems t to do so. However, in the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association vs Union of India ruling in 1993, a nine-judge bench said that the CJI must have the primal role in these appointments. In 1998, this was further reinforced when in reply to a presidential reference on the meaning of consultation, the apex court framed guidelines that led to the collegium system. It was expected that this would shield the judiciary from political interference and guard its independence. The treatment of the judiciary by the government during the Emergency and in the years following had left no doubt about how disastrous the power to appoint and transfer judges could be in the hands of the executive. The apex court dismissed a public interest litigation (PIL) in January this year pleading for the scrapping of the collegium system. Over the years, however, even the collegium system has garnered more than a fair amount of criticism for the lack of transparency and secrecy. Retired judges, convinced that extraneous considerations led to their being overlooked in the elevation to higher posts, have been articulate in their criticism. Former CJI Kabir, who retired recently, has been at the centre of

a controversy with the Chief Justice of the Gujarat High Court Bhaskar Bhattacharya accusing him of stalling his elevation to the Supreme Court on grounds of personal animosity. Not only that, it is pointed out that the collegium lacks an administrative and intelligence gathering mechanism to assist it in the appointments leading to delays and arbitrary choices as there is no minimum criteria for the selection. On the other hand, irrespective of political hue, the executive has never been comfortable with not having a role in these appointments. The increasing prominence of courts in almost all spheres of national life, especially in corruption cases, has no doubt raised the discomfort levels. More and more, public discourse is lled with how the senior judiciary has to shoulder responsibility while the executive misuses power. The National Democratic Alliance (NDA) had proposed a National Judicial Commission and now the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) has come up with the suggestion of a Judicial Appointments Commission. The latter is supposed to be headed by the CJI, with the government represented by the law minister and will include two judges of the apex court as well as two jurists nominated by the president. Even if the collegium system has faced bitter criticism on occasion, the executive cannot be allowed to call the shots. In 1987, the Law Commission in its 121st report titled A New Forum for Judicial Appointments proposed a body of 11 members with the CJI at the head and representatives of the senior judiciary, the executive, the bar and legal academics. It left out the consumer of justice the litigant saying it would not be advisable in the present state of affairs to give it representation on the commission. A number of ills plague the Indian judicial system. The distressingly large backlog of pending cases in courts from the lowest to the highest is one obvious problem. The cold statistics mask the very real human misery that this backlog generates. Although there are many other and complex issues involved, there is no doubt that a just system to appoint judges constitutes an important part of the effectiveness of the justice delivery system. A rst step would be to invite a vigorous public debate on laying down a modicum of criteria for appointments of judges at all levels of the judiciary.

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

august 10, 2013

vol xlviII no 32

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Tsja HC AbaDocument49 pagesTsja HC AbaSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Approaches To Porn-ThesisDocument0 pagesApproaches To Porn-ThesisSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Ucl Clge 008 10 PDFDocument100 pagesUcl Clge 008 10 PDFSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- September SchedulelatestDocument21 pagesSeptember SchedulelatestSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- September FinalschDocument27 pagesSeptember FinalschSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Ifc 2012Document79 pagesIfc 2012Saurav DattaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- 2008 Sex SurveyDocument6 pages2008 Sex SurveySaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Bolly QueerDocument20 pagesBolly QueerSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Cyberbullying and School SpeechDocument30 pagesCyberbullying and School SpeechSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- (ÃÖ Ù 10 ° ßÇàÈ Contents) Inter-AsiaDocument39 pages(ÃÖ Ù 10 ° ßÇàÈ Contents) Inter-AsiaSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Issue 2 2007 TarshiDocument32 pagesIssue 2 2007 TarshiSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Political Parties in The Pacific Islands PDFDocument242 pagesPolitical Parties in The Pacific Islands PDFManoa Nagatalevu Tupou100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Motion To Set For Collusion Hearing SAMPLEDocument4 pagesMotion To Set For Collusion Hearing SAMPLEAnnaliza Garcia Esperanza100% (3)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Sample Motion Re House Arrest ApprovalDocument6 pagesSample Motion Re House Arrest ApprovalBen Kanani100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Status Report On CI Project Covered CourtDocument1 pageStatus Report On CI Project Covered CourtLing PauNo ratings yet

- Decisions Stella v. Italy and Other Applications and Rexhepi v. Italy and Other Applications - Non-Exhaustion of Domestic RemediesDocument3 pagesDecisions Stella v. Italy and Other Applications and Rexhepi v. Italy and Other Applications - Non-Exhaustion of Domestic RemediesMihai IvaşcuNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lesson 3: Poverty and Inequality: BBE 4303-Economic DevelopmentDocument22 pagesLesson 3: Poverty and Inequality: BBE 4303-Economic DevelopmentMark ChouNo ratings yet

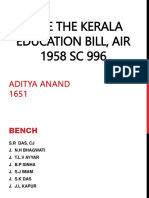

- In Re The Kerala Education Bill, Air 1958 SC 996: Aditya Anand 1651Document11 pagesIn Re The Kerala Education Bill, Air 1958 SC 996: Aditya Anand 1651Aditya AnandNo ratings yet

- Politics of Identity and The Project of Writing History in Postcolonial India - A Dalit CritiqueDocument9 pagesPolitics of Identity and The Project of Writing History in Postcolonial India - A Dalit CritiqueTanishq MishraNo ratings yet

- 13 October 2016, Jewish News, Issue 972Document43 pages13 October 2016, Jewish News, Issue 972Jewish NewsNo ratings yet

- Alpbach Summer School 2013Document5 pagesAlpbach Summer School 2013Zoran RadicheskiNo ratings yet

- Quiz 5 Contemporary WorldDocument4 pagesQuiz 5 Contemporary Worldjikjik100% (2)

- Putul Nacher Itikotha by Manik Bandopadhy PDFDocument123 pagesPutul Nacher Itikotha by Manik Bandopadhy PDFSharika SabahNo ratings yet

- Aefdtrhfgyuk0iop (Document9 pagesAefdtrhfgyuk0iop (Bethuel KamauNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Revolutionary Methods For Political Control p31Document642 pagesRevolutionary Methods For Political Control p31max_schofield100% (1)

- Anti Torture LawDocument16 pagesAnti Torture Lawiana_fajardo100% (1)

- CHU vs. GUICO (ETHICS) DocxDocument2 pagesCHU vs. GUICO (ETHICS) DocxMacky LeeNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of Indian ConstitutionDocument2 pagesSalient Features of Indian ConstitutionSiddharth MohananNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Private Trust Church AffidavitDocument1 pageDeclaration of Private Trust Church AffidavitDhakiy M Aqiel ElNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Rti PPTDocument28 pagesRti PPTadv_animeshkumar100% (1)

- Administrative LawDocument5 pagesAdministrative LawLCRO BacoorNo ratings yet

- O The Revolution: Second PhaseDocument4 pagesO The Revolution: Second PhaseLean MabsNo ratings yet

- Niel Nino LimDocument17 pagesNiel Nino LimSzilveszter FejesNo ratings yet

- Thomas Palermo and Sheldon Saltzman v. Warden, Green Haven State Prison, and Russell Oswald, 545 F.2d 286, 2d Cir. (1976)Document21 pagesThomas Palermo and Sheldon Saltzman v. Warden, Green Haven State Prison, and Russell Oswald, 545 F.2d 286, 2d Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Annex J: Sanggunian Resolution Approving AccreditationDocument2 pagesAnnex J: Sanggunian Resolution Approving AccreditationDILG Labrador Municipal OfficeNo ratings yet

- Ramsay, Captain Archibald Maule, 1952 - The Nameless WarDocument239 pagesRamsay, Captain Archibald Maule, 1952 - The Nameless Warghagu100% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- G.R. No. 2684Document2 pagesG.R. No. 2684Josephine BercesNo ratings yet

- Central University of South Bihar: Max Weber: Three Types of Legitimate RuleDocument9 pagesCentral University of South Bihar: Max Weber: Three Types of Legitimate Rulerahul rajNo ratings yet

- Articles of Incorporation and by Laws Non Stock CorporationDocument10 pagesArticles of Incorporation and by Laws Non Stock CorporationTinTinNo ratings yet

- Newsletter TemplateDocument1 pageNewsletter Templateabhinandan kashyapNo ratings yet

- Boy Scouts of The Philippines Vs NLRCDocument3 pagesBoy Scouts of The Philippines Vs NLRCYvon BaguioNo ratings yet