Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Topic of The Week: 16 To 22 January 2012: Topic: India's UID Scheme

Uploaded by

rockstar104Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Topic of The Week: 16 To 22 January 2012: Topic: India's UID Scheme

Uploaded by

rockstar104Copyright:

Available Formats

Z

Topic of the week : 16th to 22nd January 2012

Topic : Indias UID Scheme

FOR a country that fails to meet its most basic challengesfeeding the hungry, piping clean water, fixing roadsit seems incredible that India is rapidly building the worlds biggest, most advanced, biometric database of personal identities. Launched in 2010, under a genial ex-tycoon, Nandan Nilekani, the unique identity (UID) scheme is supposed to roll out trustworthy, unduplicated identity numbers based on biometric and other data. The goal, says Mr Nilekani, is to help India cope with the past decades expansion of welfare provision, the fastest in its history: it is essentially about better public services. A year ago, only a few million had enrolled and barely 1m

Moving well

identity numbers had been issued. Warnings about fragile technology, overwhelmed data-processing centres and surging costs suggested slow progress. Instead this week saw the 110-millionth UID number issued. Enrolments should reach 200m in a couple of weeks. Mr Nilekani says that over 20m people are now being signed up every month. He expects to get to 400m by the years end. That is an astonishing outcome. For a government that has achieved almost nothing since re-election in May 2009, the scheme is emerging as an example of real progress. By 2014, the likely date of the next general election, over half of all Indians could be signed up. If welfare also starts flowing direct into their accounts, the electoral consequences could be profound.

Read further : http://www.economist.com/node/21542814 http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-01-11/ranchi/30615852_1_biometric-and-demographic-datafingerprint-data-aadhaar

As it grows, however, the project is drawing fire. Most pressing, the mandate of the UID authority will expire within weeksonce the 200 millionth resident is signed up. Total costs are rising as UID expands: its budget has more than doubled from nearly 32 billion rupees ($614m) for the first five years, to over 88 billion rupees for the next phase. But the governments chief economic adviser, Kaushik Basu, among others, agrees that savings by plugging leakagesthat is, stopping huge theft and waste in welfare and subsidieswill be very big, very beneficial. The real difficulties are political. Most immediate is the home minister, P. Chidambaram, who is blocking the new mandate. He says he worries about national security. He also looks annoyed that a rival biometric scheme to build a National Population Register (for citizens, not just residents) has been cast into the shade. Run by his home ministry, by late last year it had only issued some 8m identity numbers. Last month, for example, parliaments powerful finance standing committee issued a 48-page report attacking UID, calling it hasty, directionless, ill-conceived and saying it must be stopped.

Concerns

The report contains testimony from a range of experts with legitimate objections. Some were procedural, including a demand that UID be based on law passed by parliament, not, as now, on a mere executive order. Other worries, such as cost, should abate as the unique identities are tied to bank accounts of welfare recipients, and so help track the flow of public money. The omens are good. Last week Karnataka state claimed that by paying welfare direct to bank accounts it had cut some 2m ghost labourers from a rural public-works project. activists and development economists, such as Jean Drze and Reetika Khera, worry that the voluntary programme will turn compulsory, that individuals privacy is under attack and that biometric data are not secure. Once recipients have bank accounts, India can follow the likes of Brazil and replace easily stolen benefits in kind, such as rations of cheap food and fuel, with direct cash transfers. Not only do these cut theft, but cash payments also let beneficiaries become mobilefor example so they can leave their state to seek work, while not jeopardising any benefits. However some fear that money is more easily wasted, say on alcohol. Worse, in the most remote places, cash welfare is no use since food and fuel markets do not even exist. Such fears need answering. India will have to pass a law on data protection and privacy. A shift to cash welfare would have to ensure that mothers benefit most, not feckless fathers. And perhaps only as Indians grow more urban, mobile and wellconnected will they see the full advantage of cash over rations. But for all the headaches, applying the UID to an expanding and reforming welfare system opens the way for profound social change. Indians need to get ready.

You might also like

- OrwellDocument44 pagesOrwellMarzxelo18No ratings yet

- Susi vs. RazonDocument2 pagesSusi vs. RazonCaitlin Kintanar100% (1)

- Angara Vs Electoral Commission DigestDocument1 pageAngara Vs Electoral Commission DigestGary Egay0% (1)

- Focus Writing PDFDocument25 pagesFocus Writing PDFMosiur Rahman100% (1)

- Marine Advisors With The Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970Document85 pagesMarine Advisors With The Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970Bob Andrepont100% (4)

- Rural Bank of Salinas V CADocument2 pagesRural Bank of Salinas V CAmitsudayo_100% (2)

- CBSE UGC NET 2015 Result. Check Result HereDocument501 pagesCBSE UGC NET 2015 Result. Check Result HereThe Indian Express100% (2)

- Animal Farm Background InformationDocument8 pagesAnimal Farm Background Informationbdwentz9435100% (15)

- Tucay v. Domagas (Hearing On The Application For Bail Is Necessary)Document2 pagesTucay v. Domagas (Hearing On The Application For Bail Is Necessary)kjhenyo218502No ratings yet

- India Fintech Report 2021Document29 pagesIndia Fintech Report 2021devang bohraNo ratings yet

- What Is The Purpose of ASEANDocument12 pagesWhat Is The Purpose of ASEANm3r0k050% (2)

- Partnership MandateDocument2 pagesPartnership Mandatenaseem001001No ratings yet

- ICT For Rural DevelopmentDocument8 pagesICT For Rural Developmentrockstar104No ratings yet

- Digital Economy PresentationDocument12 pagesDigital Economy Presentationgarima KhuranaNo ratings yet

- Future of Digital Economy in IndiaDocument3 pagesFuture of Digital Economy in IndiaShibashis GangulyNo ratings yet

- Risk Reduction-An Individual Does Not Need To CarryDocument5 pagesRisk Reduction-An Individual Does Not Need To CarryRAJESH MECHNo ratings yet

- India's Readiness For Digital Economy: Cashless Economy Authored by Ajit Kumar Roy, Authored by Ajit Kumar Roy, Contributions by Ajit Kumar Roy List Price: $29.99 6" X 9" (15.24 X..Document12 pagesIndia's Readiness For Digital Economy: Cashless Economy Authored by Ajit Kumar Roy, Authored by Ajit Kumar Roy, Contributions by Ajit Kumar Roy List Price: $29.99 6" X 9" (15.24 X..Akshith CpNo ratings yet

- Assignment-1: Research MethodologyDocument7 pagesAssignment-1: Research MethodologyNikita ParidaNo ratings yet

- 1,900 Indians Under Scanner For Panama Links: Gs Iii: Money LaunderingDocument22 pages1,900 Indians Under Scanner For Panama Links: Gs Iii: Money LaunderingSree HariNo ratings yet

- 2010 India Citizen MasteringDocument4 pages2010 India Citizen MasteringMagesh KesavapillaiNo ratings yet

- Shahada Nandurbar Maharashtra Manmohan Singh Sonia Gandhi: Cite Your ID Number."Document3 pagesShahada Nandurbar Maharashtra Manmohan Singh Sonia Gandhi: Cite Your ID Number."Aditi MishraNo ratings yet

- Impact of Technology On Banking SectorDocument31 pagesImpact of Technology On Banking SectorVimaljeet KaurNo ratings yet

- India Embraces Digital Payments Over Cash, Even For A 10-Cent Chai - The New York TimesDocument7 pagesIndia Embraces Digital Payments Over Cash, Even For A 10-Cent Chai - The New York TimessundarmsNo ratings yet

- Over 25,800 Online Banking Fraud Cases Reported in 2017: GovtDocument3 pagesOver 25,800 Online Banking Fraud Cases Reported in 2017: GovtdfgsgfywNo ratings yet

- However, Only About 40 Per Cent of The Population Has Internet SubscriptionDocument2 pagesHowever, Only About 40 Per Cent of The Population Has Internet SubscriptionMohit KeshriNo ratings yet

- AIR Spotlight - India's Digital Economy: ParticipantsDocument3 pagesAIR Spotlight - India's Digital Economy: Participantsanil peralaNo ratings yet

- Poverty in IndiaDocument3 pagesPoverty in IndiaSumit SharmaNo ratings yet

- India-Building An New Ecosystem - Vinayak v4Document8 pagesIndia-Building An New Ecosystem - Vinayak v4Marcos Rodríguez PuentesNo ratings yet

- Fintech IndiaDocument13 pagesFintech IndiaSourav SipaniNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document10 pagesJurnal 2Mhd Alpi SyaehruddinNo ratings yet

- Project Report Aadhar Project: World's Largest Data Management ProjectDocument17 pagesProject Report Aadhar Project: World's Largest Data Management ProjectVishnu PratapNo ratings yet

- Ban On Chinese Apps in IndiaDocument4 pagesBan On Chinese Apps in IndiaSimon JosephNo ratings yet

- Digital Payments in IndiaDocument3 pagesDigital Payments in IndiaSona DuttaNo ratings yet

- IDBI FEDERAL ProjectDocument15 pagesIDBI FEDERAL ProjectManisha KumariNo ratings yet

- India's Demonetization: Time For A Digital EconomyDocument12 pagesIndia's Demonetization: Time For A Digital EconomyRenuka SharmaNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1Document6 pagesCase Study 1mashila arasanNo ratings yet

- Assignment Marketing Management (KGNM - MMTA009)Document5 pagesAssignment Marketing Management (KGNM - MMTA009)efaz ahmadNo ratings yet

- Financial InclusionDocument3 pagesFinancial Inclusionseesi alterNo ratings yet

- On Way Towards A Cashless Economy Challenges and ODocument9 pagesOn Way Towards A Cashless Economy Challenges and OShahariar ArefeenNo ratings yet

- Indeco 2 Sem 6Document9 pagesIndeco 2 Sem 6Sahil GauravNo ratings yet

- GD - DetailsDocument2 pagesGD - DetailsJayanthi HeeranandaniNo ratings yet

- Steal of Few Hundred and YouDocument13 pagesSteal of Few Hundred and YouSubhash BajajNo ratings yet

- Demonetization Anniversary - One Year of Love Hate Story: Dr. Alka Singh, Dr. Navin KumarDocument2 pagesDemonetization Anniversary - One Year of Love Hate Story: Dr. Alka Singh, Dr. Navin KumarAnonymous lPvvgiQjRNo ratings yet

- Civil Services Mentor September 2015Document138 pagesCivil Services Mentor September 2015Asasri ChowdaryNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Current Affairs MGN329Document7 pagesSeminar On Current Affairs MGN329Ashi KhatriNo ratings yet

- Daily Current Affairs PIB 02 November 2019Document12 pagesDaily Current Affairs PIB 02 November 2019HarishNo ratings yet

- Institute Name: S. P. Jain Institute of Management and Research, Mumbai Team Name: White Knights Team MembersDocument8 pagesInstitute Name: S. P. Jain Institute of Management and Research, Mumbai Team Name: White Knights Team MemberskulkapNo ratings yet

- 11 Mar, 2023Document23 pages11 Mar, 2023pradeepNo ratings yet

- 70 Mba 104Document4 pages70 Mba 104Jd GuptaNo ratings yet

- Indias Stalled RiseDocument12 pagesIndias Stalled RiseParul RajNo ratings yet

- China in A Changing Region FE 020113Document1 pageChina in A Changing Region FE 020113Dr Vidya S SharmaNo ratings yet

- CII Report Digital IndiaDocument11 pagesCII Report Digital IndiaRenuka SharmaNo ratings yet

- (NY Times Article) India Takes Aim at Poverty With Cash Transfer Program - NYTimesDocument4 pages(NY Times Article) India Takes Aim at Poverty With Cash Transfer Program - NYTimesluizriconNo ratings yet

- TAXATIONDocument4 pagesTAXATIONYuvraj SinghNo ratings yet

- COA - Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesCOA - Reaction PaperMachi KomacineNo ratings yet

- India: Vanshika Jain - Group-6 - P250 Economic and Political OutlineDocument3 pagesIndia: Vanshika Jain - Group-6 - P250 Economic and Political OutlineVANSHIKA JAINNo ratings yet

- Financial Inclusion A Gateway To Reduce Corruption Through Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT)Document7 pagesFinancial Inclusion A Gateway To Reduce Corruption Through Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT)archerselevatorsNo ratings yet

- 2IJMSATCAP101Document17 pages2IJMSATCAP101mitu afrinNo ratings yet

- Essay GD PI TopicsDocument3 pagesEssay GD PI Topicscijerep654No ratings yet

- Economics InternshipDocument4 pagesEconomics InternshipNakul ChavdaNo ratings yet

- Cause of Ban On Chinese ApplicationsDocument5 pagesCause of Ban On Chinese ApplicationsElden GonsalvesNo ratings yet

- Analysis of FII Data 2013 & 2018 - MA EconomicsDocument27 pagesAnalysis of FII Data 2013 & 2018 - MA EconomicsSaloni SomNo ratings yet

- INSIGHTS DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS PIB SUMMARY - 12 October 2020Document17 pagesINSIGHTS DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS PIB SUMMARY - 12 October 2020PranavNo ratings yet

- Data Localization Issues in Information TechnologyDocument3 pagesData Localization Issues in Information TechnologyRaghuraman KalyanaramanNo ratings yet

- Essay-11 Economic IssuesDocument19 pagesEssay-11 Economic IssuesShretima AgrawalNo ratings yet

- A. Muh. Alif Rumansyah - 185020307111031 - THE IMPACT OF CORONA VIRUS IN INDIADocument10 pagesA. Muh. Alif Rumansyah - 185020307111031 - THE IMPACT OF CORONA VIRUS IN INDIAalif rumansyahNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs AssignmentDocument12 pagesCurrent Affairs AssignmentSubham PalNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and The Future of Microfinance: Evidence and Insights From PakistanDocument31 pagesCOVID-19 and The Future of Microfinance: Evidence and Insights From PakistanShameel IrshadNo ratings yet

- India's IT IndustryDocument3 pagesIndia's IT IndustryTanushree PaiNo ratings yet

- The Hindu Opinion Lead Hard Questions About Soft QuestionsDocument3 pagesThe Hindu Opinion Lead Hard Questions About Soft Questionssam3086No ratings yet

- UGC NET Paper II December 2011Document2 pagesUGC NET Paper II December 2011rockstar104No ratings yet

- Bachelor of Technology - Integrated Project ReportDocument1 pageBachelor of Technology - Integrated Project Reportrockstar104No ratings yet

- MTMDocument7 pagesMTMrockstar104No ratings yet

- Nov IIP Shrinks To 6-Month Low at 2.1% On Weak Consumption: Consumer Confidence Is DownDocument2 pagesNov IIP Shrinks To 6-Month Low at 2.1% On Weak Consumption: Consumer Confidence Is Downrockstar104No ratings yet

- UP Rape Incidents Can Effect Tourism, Foreign Exchange Earnings: AssochamDocument1 pageUP Rape Incidents Can Effect Tourism, Foreign Exchange Earnings: Assochamrockstar104No ratings yet

- Surprise: Diesel Cars Lose Steam, Maruti Suzuki, Hyundai Motor Sales Zoom On Petrol VariantsDocument1 pageSurprise: Diesel Cars Lose Steam, Maruti Suzuki, Hyundai Motor Sales Zoom On Petrol Variantsrockstar104No ratings yet

- System Concepts: Input Involves Capturing and Assembling Elements ThatDocument141 pagesSystem Concepts: Input Involves Capturing and Assembling Elements Thatrockstar104No ratings yet

- Home About Us Administration Programmes Admission Photo Gallery Contact UsDocument12 pagesHome About Us Administration Programmes Admission Photo Gallery Contact Usrockstar104No ratings yet

- Delhi - Ranthambhore - Jaipur - Bharatpur - Agra - Khajuraho - Varanasi - Katni - Bandhavgarh - DelhiDocument7 pagesDelhi - Ranthambhore - Jaipur - Bharatpur - Agra - Khajuraho - Varanasi - Katni - Bandhavgarh - Delhirockstar104No ratings yet

- Plugin ArchiveDocument2 pagesPlugin Archiverockstar104No ratings yet

- MDF Plug in ArchiveDocument22 pagesMDF Plug in Archiverockstar104No ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility in The Tourism Industry. Some Lessons From The Spanish ExperienceDocument31 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility in The Tourism Industry. Some Lessons From The Spanish Experiencerockstar104No ratings yet

- Uttar Pradesh: Uttar Pradesh, The Heartland of India, Is Known For ItsDocument12 pagesUttar Pradesh: Uttar Pradesh, The Heartland of India, Is Known For Itsrockstar104No ratings yet

- Airline Name Airline Name: AS AQ HP AA AP CO DL HA YX NW WN FF TW UA US FLDocument1 pageAirline Name Airline Name: AS AQ HP AA AP CO DL HA YX NW WN FF TW UA US FLrockstar104No ratings yet

- Five Year Plans in India PDFDocument13 pagesFive Year Plans in India PDFrockstar104100% (1)

- Group 1 - (Roll No 1.2.3.4.5)Document12 pagesGroup 1 - (Roll No 1.2.3.4.5)rockstar104No ratings yet

- MGMTDocument10 pagesMGMTrockstar104No ratings yet

- OB MeeeeDocument6 pagesOB Meeeerockstar104No ratings yet

- Statutory Research OutlineDocument3 pagesStatutory Research OutlineYale Law LibraryNo ratings yet

- Pcadu Empo May 23Document46 pagesPcadu Empo May 23Mabini Municipal Police StationNo ratings yet

- 2Document8 pages2Bret MonsantoNo ratings yet

- Right To Information Act 2005Document42 pagesRight To Information Act 2005GomathiRachakondaNo ratings yet

- Cmi Illegal Immigrants in MalaysiaDocument11 pagesCmi Illegal Immigrants in MalaysiaKadhiraven SamynathanNo ratings yet

- National Moot Court 2017-2018-1Document10 pagesNational Moot Court 2017-2018-1ShobhiyaNo ratings yet

- Sem3 SocioDocument15 pagesSem3 SocioTannya BrahmeNo ratings yet

- H. V. Emy - Liberals, Radicals and Social Politics 1892-1914 (1973, CUP Archive) PDFDocument333 pagesH. V. Emy - Liberals, Radicals and Social Politics 1892-1914 (1973, CUP Archive) PDFDanang Candra Bayuaji100% (1)

- Thaksin Shinawatra: The Full Transcript of His Interview With The TimesDocument27 pagesThaksin Shinawatra: The Full Transcript of His Interview With The TimesRedHeartGoNo ratings yet

- Cornell Notes 5Document5 pagesCornell Notes 5api-525394194No ratings yet

- Disinvestment Performance of NDA & UPA GovernmentDocument9 pagesDisinvestment Performance of NDA & UPA GovernmentDr VIRUPAKSHA GOUD GNo ratings yet

- Daniel Holtzclaw: Brief of Appellee - Filed 2018-10-01 - Oklahoma vs. Daniel Holtzclaw - F-16-62Document57 pagesDaniel Holtzclaw: Brief of Appellee - Filed 2018-10-01 - Oklahoma vs. Daniel Holtzclaw - F-16-62Brian BatesNo ratings yet

- Session 3 - Presentation - The IMF's Debt Sustainability Framework For Market Access Countries (MAC DSA) - S. Ali ABBAS (IMF)Document18 pagesSession 3 - Presentation - The IMF's Debt Sustainability Framework For Market Access Countries (MAC DSA) - S. Ali ABBAS (IMF)untukduniamayaNo ratings yet

- Home Department Govt. of Bihar: Seniority List of Ips Officers of The Rank of Deputy Inspector General (D.I.G.)Document2 pagesHome Department Govt. of Bihar: Seniority List of Ips Officers of The Rank of Deputy Inspector General (D.I.G.)sanjeet kumarNo ratings yet

- Lederman V Giuliani RulingDocument14 pagesLederman V Giuliani RulingRobert LedermanNo ratings yet

- Agent Orange CaseDocument165 pagesAgent Orange CaseזנוביהחרבNo ratings yet

- Question BankDocument9 pagesQuestion BankAshita NaikNo ratings yet

- Joel Jude Cross Stanislaus Austin CrossDocument1 pageJoel Jude Cross Stanislaus Austin Crossjoel crossNo ratings yet

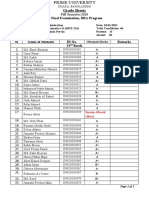

- Grade Sheet S: Final Examination, BBA ProgramDocument2 pagesGrade Sheet S: Final Examination, BBA ProgramRakib Hasan NirobNo ratings yet

- 98Document1 page98Muhammad OmerNo ratings yet

- Adtw e 1 2009Document3 pagesAdtw e 1 2009Vivek RajagopalNo ratings yet