Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Illegitimacy: and Illegitimate Concept

Uploaded by

Anwesha TripathyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Illegitimacy: and Illegitimate Concept

Uploaded by

Anwesha TripathyCopyright:

Available Formats

Submitted To and Guided By: Dr.Shaiwal Satyarthi Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, Chanakya National Law University.

Family Law Project Report On:

ILLEGITIMACY

-an illegitimate concept

Submitted By: Anwesha Tripathy IInd Year(3rd Sem),Roll No.724, Section- A. Chanakya National Law University

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

It is my greatest pleasure to be able to present this project of Family Law. I found it very interesting to work on this project. I would like to thank Dr.Shaiwal Satyarthi, Associate.Prof., Faculty of law,Chanakya National Law University for providing me with such an interesting project topic,for his unmatched efforts in making learning an enjoyable process,for his immense sincerity for the benefit of his students and for his constant unconditional support and guidance.

I would also like to thank my librarian for helping me in gathering data for the project. Above all, I would like to thank my parents, elder sister and paternal aunt,who from such a great distance have extended all possible moral and motivative support for me.

I hope the project is upto the mark and is worthy of appreciation.

Anwesha Tripathy Patna

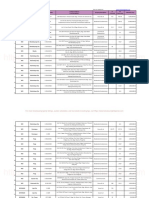

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgement 1. Introduction 2. Void and Voidable Marriages 3. Legitimacy of children born out of Void and Voidable Marriages 4. Law to confer legitimacy 5. Great need for reforms 6. Conclusion Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

Marriages are regarded as a fundamental social institution, and instrumental in the process of society building. Loaded with ethical, personal, social and religious values, marriages are a very important affair in any individuals life. Therefore, this institution has come to be governed by Personal Laws of all religions. Considering the importance of a marriage, it was necessary for it to have procedures to be regarded as an authentic and recognized institution binding two individuals and thus indirectly two families indirectly. Thus law has worked on authenticating and validating marriages, and has subsequently laid down rules regarding the same and for any contravention to the rules. Any marriage thus can fall into the category of either valid marriage if solemnized in adherence to the laid down rules, or, void and voidable marriages in case of any contravention to the rules. In a valid marriage, no complication or query regarding rights, property, issues etc. is involved. However, several questions are attached to the void and voidable marriages, the most important being that regarding the social status of children born out of such marriages. Children born out of such marriages which the law either does not accept or has rendered null are illegitimised for no fault of theirs. The social stigma attached to such a child is a matter of concern both from legal and humanitarian grounds. The rights and benefits to such a child becomes questionable and so does his/her very identity. Thus law had to intervene to address this pertinent issue and design provisions for same. All personal laws have rules and essentials for a valid marriage and any contravention shall make it a void marriage. In this project we shall see the provisons for children born out of such marriages under various laws. Research Methodology For the purpose of research, the researcher has used the Doctrinal Method of Research. The Research is entirely a Library-based Research, where the researcher has made use of books, law journals, magazines, law reports, legislations, internet websites, etc., for the purpose of research. Sources of Data The entire research work has been done in the library and on the internet websites. Thus, the sources of data include the books, e-books, law journals, online law journals, law reports, and various concerned legislations.

Aims and Objectives The main purpose behind this Research work is to study the various instances of legitimacy of children under void and voidable marriage. This project shall discuss in detail the situations under various personal laws relating to conferring of legitimacy of the children born under void and voidable marriage. Scope The Project shall be limited to the discussion on the status of the child under void and voidable marriage, and shall not exceed to a further discussion on the rights of this child.

VOID AND VOIDABLE MARRIAGES

A marriage, which is not valid, may be void or voidable. A void marriage is one which has no legal status. The courts regard such marriage as never having taken place and no rights and obligations ensue. It is void ab initio, i.e., right from its inception. Hence the parties are at liberty to contract another marriage without seeking a decree of nullity of the first so-called marriage. A voidable marriage on the other hand, is a marriage which is binding and valid, and continues to subsist for all purposes until a decree is passed by the court annulling the same. Thus, so long as such decree is not obtained, the parties enjoy all the rights and obligations which go with the status of marriage. A remarriage by any of the parties without a decree of nullity is illegal as it would amount to bigamy. Distinction between Void and Voidable Marriage The distinction between a void and voidable marriage, in a nutshell, is: (i) A void marriage has no legal status right from the beginning, whereas a voidable marriage has all the rights and obligations of matrimony until it is annulled by court. (ii) A void marriage may be declared a nullity at the instance of either party, whereas, in a voidable marriage, the court can pass a decree of annulment at the instances of the aggrieved party. Statutory provisions regarding Void, Voidable and Irregular Marriage Hindu Law A marriage solemnized in contravention of the following conditions is void under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955,1 when: (i) (ii) Either party has a spouse living at the time of marriage; Parties are within the degrees of prohibited relationship, unless custom or usage governing them permits such marriage; (iii)

1

The parties are sapindas of each other, unless custom or usage permits such marriage.

Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, s. 11 read with s. 5.

A marriage is voidable under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 under the following conditions,2 viz: (i) The marriage has not been consummated owing to the impotence of the respondent; or (ii) Any of the parties is incapable of giving a valid consent because of unsoundness of mind, or though capable of giving consent, has been suffering from mental disorder to such an extent as to be unfit for marriage and pro-creation of children, or has been subject to recurrent attacks of insanity; (iii) (iv) The consent to the marriage has been obtained by force or fraud; The respondent was pregnant at the time of marriage by some other person other than the petitioner.

Special Marriage Act, 1954 Under the Special Marriage Act, 1954, a marriage is null and void under s. 4 read with s. 24, if: (i) It is in violation of the minimum age requirement, which is 21 years for a boy and 18 years for a girl; (ii) (iii) There is another spouse living; The parties are within the prohibited degrees of relationship, unless custom or usage permits such marriage; (iv) Any of the parties is incapable of giving valid consent due to unsoundness of mind, or though capable of giving consent, is suffering from mental disorder of such kind as to be unfit for marriage or procreation of children, or has been subject to recurrent attacks of insanity; (v) The respondent was impotent at the time of marriage and at the time of filing of the suit.

A marriage under the Special Marriage Act, 1954 is voidable if the same has not been consummated owing to willful refusal of the respondent, or the respondent was pregnant by

2

Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, s. 12.

some person other than the petitioner, or the consent of either party to the marriage was obtained by coercion or fraud.3

Parsi Law The Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936,4 lays down that a second marriage without divorce in case of an earlier marriage is void. A marriage where consummation of the marriage is impossible from natural causes, may, at the instance of either party to the marriage, be declared null and void.

Christian Law Under the Indian Divorce Act, 1869,5 a marriage may be declared null and void on the following grounds, viz: (i) The respondent was impotent at the time of marriage and at the time of institution of the suit; (ii) (iii) (iv) The parties are within prohibited degree of consanguinity or affinity; Either party was a lunatic or idiot at the time of marriage; The former husband or wife of either party was living at the time of the marriage and the earlier marriage was subsisting. Muslim Law Under the Muslim law, a marriage, which is not sahih, i.e., valid, may be either, batil, i.e., void, or fasid, i.e., irregular.6 Batil: Such marriage being void does not create any rights or obligations, and the children born of such union are illegitimate. A marriage will be void if it is with a mooharin, i.e., prohibited by

3 4

Special Marriage Act, 1954, s. 25. Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936, s. 4. 5 Indian Divorce Act, 1869, Ss. 18 and 19. 6 Irregular marriage under Sunni Law is void under Shia Law.

reasons of: (a) consanguinity, (b) affinity, or (c) fosterage. A marriage with the wife of another man or remarriage with a divorced wife when the legal bar still exists, is also void. Such marriage being void, there are no rights and obligations between the parties. A wife has no right to dower unless there has been consummation, in which case she is entitled to customary dower. Besides, if one of the parties dies, the other is not entitled to inherit from the deceased. Fasid: Such marriage is irregular because of the lack of some formality, or the existence of some impediment which can be rectified. Since the irregularity is capable of being removed, the marriage is not unlawful in itself. Marriage in the following circumstances is fasid, viz., a marriage that is: (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) Without witnesses; With a fifth wife by a person having four wives; With a woman undergoing iddat; Prohibited by reason of difference of religion; With a woman so related to the wife, that if one of them had been a male, they could not have lawfully intermarried. In the above situations, the prohibition against such marriages is temporary or relative or accidental, and can be thus rectified: (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) By subsequent acknowledgement before witnesses; By divorcing one of the four wives; By expiration of the iddat period; By the woman becoming a convert to Islam, Christianity or Jewish religion, or the husband adopting Islam; (v) By the man divorcing the wife who constitutes the obstacle.

In Chand Patel v. Bismillah Begum,7 the issue was whether a person professing Muslim faith who contracts second marriage with wifes sister during the subsistence of the earlier marriage is obliged to pay maintenance to such woman under the provisions of s. 125 of the Cr.P.C. The Court held that such a marriage was not void but only irregular; if it a temporarily prohibited

7

AIR 2008 SC 1915: (2009) 4 SCC 774.

10

marriage and could always become lawful by death of first wife or by husband divorcing the first wife. Since a marriage which is temporarily prohibited may be rendered lawful once the prohibition is removed, such a marriage is in our view irregular (fasid) and not void (batil), the court observed. An irregular marriage may be terminated by either party, either before or after consummation. It has no legal effect before consummation. If, however, consummation has taken place, then: (i) (ii) The wife is entitled to dower, prompt or specified, whichever is less; She is bound to observe iddat, the duration of which, in case of both divorce or death, is three courses; (iii) Children born of the marriage are legitimate.

It is significant to note that an irregular marriage, even if consummated, does not create mutual rights of inheritance between the parties.8

Mulla, Principles of Mohammedan Law, 1972, pp. 261-63, paras 264(3) and 267.

11

LEGITIMACY OF CHILDREN BORN OUT OF VOID AND VOIDABLE MARRIAGES

The conditions for a void marriage are laid down under all personal law statutes. While breach of some conditions is considered more serious and the marriage is rendered void, non-compliance of others renders a marriage voidable only. The basic distinction between a void and voidable marriage is that while in the former there is no legal status conferred on the parties and the marriage is void ab initio, i.e., right from inception, in the latter, all rights and obligations of matrimony subsist until the marriage is annulled by the court. Besides, a void marriage may be declared a nullity at the instance of either party, but in case of voidable marriage, the decree of annulment can be made by the court at the instance of the aggrieved party.

Hindu Law As regards the status of children, while children of voidable marriage were legitimate, those born out of void marriage were considered to be illegitimate under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, 9 (prior to 1976), unless the parties to such marriage obtain a decree of annulment in respect of the marriage. In other words, if any of the parties to the marriage do not choose to make a petition under s. 11, the children of such marriage remain illegitimate, and if any of the parties to such marriage dies before any such decree is passed, the children would not be protected. Thus, in a suit by the second wife of a deceased and her minor daughter against the children by the first wife for partition of the estate of the deceased, it was held that the second marriage was void since it had taken place after the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 came into force, and the first wife being alive, the deceased could not have taken the second wife; it was also held that that the child by the second wife was illegitimate and could not be regarded as legitimate under s. 16 of the Act, since marriage was not declared void on a petition under s. 11.10 However, children of void and voidable marriage, which has been annulled by a decree, were deemed to be the legitimate children of such properties for the purpose of inheriting their parents property.

9 10

Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, s. 16. Thulsi Ammal v. Gauri Ammal, AIR 1964 Mad 118.

12

Though the provision in s. 16 aimed at protecting the rights of children whose parents marriage suffered from a legal flaw, it did not serve this purpose as children could be legitimated only if the parents obtained a decree of nullity. If the parents failed to go to court for such decree, the children remained illegitimate. This provision was criticized in several judgments, as it appeared to be inconsistent with the intention of the legislature, which obviously was not to render children of a void marriage illegitimate if a decree to that effect was not obtained. This issue was deliberated by the Law Commission and there were two proposals made, viz: (i) (ii) The condition of a decree of nullity should be done away with; and The section should apply only if at the time of intercourse resulting in birth (or at the time of celebration of the marriage where marriage takes place after intercourse) both or either of the parties reasonably believed that the marriage was valid. The latter proposal did not find favor. It was pointed out that in the context of the status of children born of a void marriage, four options could be possible: (i) (ii) Such children should be regarded as filius nullius with no status; They should be deemed legitimate for purposes of succeeding to their parents, provided the marriage was contracted bona fide without knowledge of any impediment; (iii) (iv) They should be entitled to succeed to their parents in all cases; They should be entitled to succeed to other relations in all cases.

The Law Commission found the third view as most acceptable, as it was fair to the innocent children and also in harmony with changing social opinion. While it did not give legitimacy to the marriage relationship as such, it sought to mitigate the hardship on children. The Commission therefore, recommended revision of s. 16. In 1976, the section was amended.11 Consequent to the amendment, the position under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 and the Special Marriage Act, 1954 is that, notwithstanding that no decree of nullity has been obtained in the case of a void or voidable marriage, the children would be deemed to be legitimate as if the marriage was valid.

11

Vide Marriage Laws Amendment Act, 68 of 1976; Special Marriage Act, 1954, s. 26 was similarly amended.

13

Section 16 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 reads as follows: 16. Legitimacy of children of void and voidable marriages- (1) notwithstanding that a marriage is null and void under section 11, any child of such marriage who would have been legitimate if the marriage had been valid, shall be legitimate, whether such child is born before or after the commencement of the Marriage Laws. (Amendment) Act, 1976, (68 of 1976.) and whether or not a decree of nullity is granted in respect of that marriage under this Act and whether or not the marriage is held to be void otherwise than on a petition under this Act. (2) Where a decree of nullity is granted in respect of a voidable marriage under section 12, any child begotten or conceived before the decree is made, who would have been the legitimate child of the parties to the marriage if at the date of the decree it had been dissolved instead of being annulled, shall be deemed to be their legitimate child notwithstanding the decree of nullity. (3) Nothing contained in sub-section (1) or sub-section (2) shall be construed as conferring upon any child of a marriage which is null and void or which Is annulled by a decree of nullity under section 12, any rights in or to the property of any person, other than the parents, in any case where, but for the passing of this Act, such child would have been incapable of possessing or acquiring any such rights by reason of his not being the legitimate child of his parents. At the outset it may be mentioned that the constitutional validity of this section was challenged in P.E.K. Kalliani Amma v. K. Devi,12 wherein the Supreme Court held that s.16 is not ultra vires the Constitution. In view of the legal fiction contained in s. 16, the illegitimate children, for all practical purposes, including succession to the property of their parents, have to be treated as legitimate, property rights, however are limited to the properties of the parents. A mention may be made of a few cases on the point. In Rameshwari Devi v. State of Bihar,13 the Supreme Court acknowledged children born of a legally valid marriage and children born of a

12

AIR 1996 SC 1963: (1996) 4 SCC 76 appeal against Kerala High Court judgment in K.E.M. Kaliani v. K. Devi, AIR 1989 Ker 279. 13 AIR 2000 SC 735: (2000) 2 SCC 431.

14

void marriage on an equal status. The case concerned payment of family pension and death-cumretirement gratuity to two wives and their sons. The deceased had entered into a second marriage while his first marriage was subsisting. He had one son from the first marriage and four sons from the second bigamous marriage, and hence void marriage. The High Court held that sons of both wives were equally entitled to a share in the family pension and death-cum-retirement gratuity, while the second wife would not be entitled to anything. In appeal to the Supreme Court against this order, the first wife argued that the second marriage being void and no marriage in the eyes of the law, the children born of the relationship had no rights. The court, however, held that though the second wife could not be termed as the widow of the deceased, the fact that she lived with him for 24 years as his wife and had four sons from him was established. While she would not be entitled to any share, her sons would get equal rights along with the first widow and her son, the court held. Likewise, in G. Nirmalamma v. G. Seethapathi,14 where the marriage was void as it took place during the subsistence of the earlier marriage of the deceased with the mother of the son, it was held that the son has to be equated with the sons of the earlier marriage, as legal heirs under ss. 8, 10 and the Schedule annexed to the Hindu Succession Act, 1956. The son, according to the court, has to be treated as coparcener of property held by the father whether the property was originally joint family property or not. The only limitation being that during the lifetime of the father, son of a void marriage is not entitled to seek a partition. In Jinia Keotin v. Kumar Sitaram Gounder,15 while reiterating that by a fiction of law children born of void or voidable marriage are deemed to be legitimate emphasized that their property rights are confined only to the parents. The argument that once status of legitimacy has been conferred they should be treated at par for purposes of inheritance with children born in wedlock was rejected. Any attempt to do so would amount to doing not only violence of the provision specifically engrafted in sub-s. (3) of s. 16 of the Act, but also would attempt to court relegislating on the subject under the guise of interpretation against the will expressed in the enactment, the court held.

14 15

AIR 2001 AP 104 (2008) 8 MLJ 985.

15

Lamenting on this restrictive provision, the Kerala High Court in the case of Krishna Kumari Thampuran v. Palace Admn. Board observed;16 For the indiscretion of the parents, the poor innocent children should not be made to suffer but at the same time by that legal fiction the right of others shall not be affected, and therefore, the rights of such children are confined to the property of parents who alone are responsible for the difficult position children are put in. Thus, in Shahaji Asme v. Sitaram Konde Asme,17 also which was a case of inheritance, it was held that as per the provisions of s. 16(3) of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, illegitimate children are entitled to inherit property of their parents alone and parents does not include grandparents. Where, however, a father is the sole coparcener at the time of his death, the coparcenary property held by him is his separate and exclusive property to which such child would be entitled.18 In Pashupati Nath Singh v. State of Bihar,19 the issue of compassionate appointment of the son of second void marriage was involved; while the District Compassionate Appointment Authority rejected his claim, on appeal the court held that the policy decision for compassionate appointment refers only to a son and as son of second wife is also a legitimate son under s. 16, his claim for compassionate appointment cannot be rejected. The provision under the Special Marriage Act, 1954 is the same as under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955.20 Parsi Law Under the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 193621 as amended in 1988: notwithstanding that a marriage is invalid under any of the provisions of sub-s. (1) of s. 3 any child of such marriage who would have been legitimate if the marriage had been valid, shall be legitimate. The conditions prescribed for a marriage under s. 3(1) are that the parties should not be within the prohibited degrees of consanguinity or affinity as prescribed; it should be solemnized according

16 17

2006(4) KLT 432. AIR 2010 Bom 24. 18 Chikkamma v. N. Suresh, 2000(4) Kant LJ 468. 19 2005(3) PLJR 458 (Pat). 20 Special Marriage Act, 1954, s. 26. 21 Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936, s. 3(2).

16

to the Parsi form of ceremony called Ashirvad and the parties should not be below the age of 21 in case of boy and 18 in case of girl. Thus only children born of a marriage solemnized in contravention of any of these conditions would be deemed to be legitimate.

Christian Law Under the Indian Divorce Act, 1869, children of marriage annulled on ground of bigamy contracted in good faith and with full belief of the parties that the former spouse was dead, or on the ground of insanity, are entitled to succeed in the same manner as legitimate children, to the estate of the parent who, at the time of the marriage was competent to contract. 22 Thus, if a father is incompetent to enter into a marriage because of insanity or because his former wife was alive, then the children will succeed only to the mother and not to the father. This is a very unfair and illogical provision. It does not confer status of legitimacy, but only a concession under certain situations, to succeed to the estate of a parent who is competent to contract the marriage. It is pertinent to note that children born of a marriage which is void for reasons other than the two mentioned above, have no legal status at all. Thus children born of a marriage prohibited degrees of consanguinity or affinity, or of a marriage where the husband is impotent, are not covered by s. 21 of the Indian Divorce Act, 1869 and therefore do not enjoy status of even partial legitimacy like children of bigamous marriage or a marriage which is void for reasons of insanity. Even the amendment of the Act in 2001 has not made any change in the original provision.

Muslim Law Muslim law does not recognize legitimation, and a child who is clearly illegitimate under the law cannot be conferred a status of legitimacy. A child can, however be acknowledged as legitimate in certain situations viz., where: (i)

22

Paternity of the child is either not known or is not established beyond doubt;

Indian Divorce Act, 1869, s. 21.

17

(ii) (iii)

It is not proved that the child is the offspring of illicit intercourse (zina); and The circumstances are such that marriage between the acknowledger and the mother is not impossibility.

This is known as the doctrine of acknowledgement of paternity. A valid acknowledgement is not revocable and gives rights of inheritance to the child. This doctrine of acknowledgement of paternity is, however, different from legitimation as provided under the other personal laws.23

23

Fyzee, Outlines of Mohammedan Law, 1974, p. 196; Mulla, Principles of Mohammedan Law, 1972, p. 328.

18

LAW TO CONFER LEGITIMACY

In a situation when a child is in the danger of illegitimisation due to the fault in the marriage of his/her parents, law comes to the rescue of the child which is/is to be illegitimised by the society and ironically the law itself. Thus an illegitimate child becomes legitimate when law deems it legitimate and confers on him/her the status of legitimacy. The question here, however, is on what basis does the law grant this legitimacy to a child born out of a void or voidable marriage. It does so on the basis of a legal fiction or hypothesis. Earlier the hypothesis was the same for void and voidable marriages. But in the recent developments, the law now confers legitimacy on children born out of void and voidable marriages basing on two separate hypotheses. When the fact in concern is that the marriage is void, then the law shall confer legitimacy on the child basing on the fiction : IF THE MARRIAGE HAD BEEN VALID, THEN THE CHILD WOULD HAVE BEEN LEGITIMATE. Marriage under any other provision than the provision in question is also covered under this. It does not matter whether a decree of nullity has been granted by the Court of Law or not. When the fact in concern is that if the marriage is voidable, i.e, it is valid until annulled by the Court of Law, then the legal fiction upon which law shall make the child legitimate will be: THE CHILD WOULD HAVE BEEN LEGITIMATE IF THE MARRIAGE WOULD HAVE BEEN DISSOLVED AT THE TIME OF THE ANNULMENT OF THE MARRIAGE. Therefore, the same law which makes a child born out of void and voidable marriages illegitimate, later confers legitimacy on the innocent being.

19

GREAT NEED FOR REFORMS

The law distinguishes between persons born in wedlock and persons born out of wedlock. The distinctions are to the disadvantage of the person born out of wedlock, and we see no reason why the law should not do what it can to remove that disadvantage. To that end, the legal distinction between legitimate children and illegitimate children be done away with. The law should so far as possible give equal treatment to all children, but it does not follow that it should apply precisely the same rules to children born out of wedlock as it does to those born in wedlock. It recognizes the father and mother of a child born in wedlock as joint guardians of the child, but we think that it is not necessarily in the best interest of children born out of wedlock that that rule apply. Therefore the rule should be that the father and mother be joint guardians only if a stable relationship exists between them at the birth of their child out of wedlock; in other cases the law can continue automatically to recognize only the mother as guardian, but it should allow the father to become a guardian if he can show that that arrangement is in the best interest of the child. In order to give effect to the principle of equal treatment by the law and to give effect to the principle that guardianship should be conferred only in the best interest of the child, a number of recommendations can be made. These could be that there be one status for all children; that the legal relationship of child and parent be dependent on their biological relationship; that, with the exception of parental guardianship, all rights and obligations of the child born out of wedlock, of a parent, or of any other person be determined in the same way as if the child were born in wedlock; that the father of a child born out of wedlock be a guardian if there is a stable relationship between himself and the child's mother; and that in the absence of a stable relationship the father have the right to be appointed guardian by the court if the

appointment is in the best interest of the individual child concerned.

20

CONCLUSION

Marriage is the foundation of a stable family; it accords status and security to the parties and their offspring. All legal systems provide for conditions for a valid marriage. It is, in the interest of the society therefore, that families keep intact, and fewer situations of void or voidable marriages arise. If, however, any such discrepancy arises, the Court tries to bring such a situation where the interest of the child born of such illegitimate relation is protected. Keeping in mind the notion that the welfare of child is paramount, the Court, by all means, has tried to confer legitimacy to the child born of of such relations, as, it is only the relation that can be illegitimate and not the child born out of it.

21

BIBLIOGRAPHY

V.P. Bharatiya, Syed Khalid Rashids Muslim Law, (4th ED. : 2004) (Eastern Book Company Lucknow) Dr.Paras Diwan, Law of Marriage and Divorce, (5th ED. : 2008), (Universal Law Publishing Co) M.N.Das, Marriage and Divorce, (6th ED. : 2002) (Eastern Law House New Delhi) A.G.Gupte, Hindu Law, (1st ED. : 2003) (Premier Publishers Delhi) S.P.Gupte, Hindu Law in British India, (2nd ED. : 1947) (Premier Publishers Delhi) Asaf A.A.Fyzee, Outlines of Muhammadan Law, (5th ED. : 2008) (Oxford University Press New Delhi) https://www.google.co.in/#q=concept+of+illegitimacy+of+children http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1287264?uid=3737496&uid=2&uid=4&sid=2110 2764750571 http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Illegitimate+children http://www.lawreform.ie/_fileupload/Reports/rIllegitimacy.html

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Anwesha Consti 2Document29 pagesAnwesha Consti 2Anwesha TripathyNo ratings yet

- INTERNATIONAL Trade LAW PROJECTDocument21 pagesINTERNATIONAL Trade LAW PROJECTAnwesha Tripathy100% (1)

- Law Relating To Human Rights Final DraftDocument36 pagesLaw Relating To Human Rights Final DraftAnwesha TripathyNo ratings yet

- Admin ProjectDocument20 pagesAdmin ProjectAnwesha TripathyNo ratings yet

- Anwesha CyberDocument29 pagesAnwesha CyberAnwesha TripathyNo ratings yet

- Ihl Final DraftDocument26 pagesIhl Final DraftAnwesha TripathyNo ratings yet

- Anwesha Juris 2Document31 pagesAnwesha Juris 2Anwesha TripathyNo ratings yet

- Admin ProjectDocument20 pagesAdmin ProjectAnwesha TripathyNo ratings yet

- INTERNATIONAL Trade LAW PROJECTDocument21 pagesINTERNATIONAL Trade LAW PROJECTAnwesha Tripathy100% (1)

- Professional EthicsDocument19 pagesProfessional EthicsAnwesha TripathyNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- RelationshipDocument3 pagesRelationshipKoyalkar RenukaNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document32 pagesModule 2Andrew BelgicaNo ratings yet

- Family Member VocabularyDocument1 pageFamily Member VocabularyEduardo Daniel Ortiz TorresNo ratings yet

- Marriage Law of The People's Republic of China (1950) PDFDocument25 pagesMarriage Law of The People's Republic of China (1950) PDFSergioNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-559296035No ratings yet

- Action PlanDocument6 pagesAction PlanJade SebastianNo ratings yet

- Mixed Used Development and Residential Hotel, CondominiumDocument57 pagesMixed Used Development and Residential Hotel, Condominium17 075 Yasa AdnyanaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document4 pagesLecture 3CeciliaNo ratings yet

- QUIZZES Nos.1 5Document4 pagesQUIZZES Nos.1 5Ïñîēl Çøsmë100% (1)

- Housing - Harvard Housing Types/ Housing PortfolioDocument9 pagesHousing - Harvard Housing Types/ Housing PortfolioТомић ЕминаNo ratings yet

- Bank of Commerce Ropa Pricelist - Metro Manila As of 2nd QTR, 2022Document9 pagesBank of Commerce Ropa Pricelist - Metro Manila As of 2nd QTR, 2022Reinald VillarazaNo ratings yet

- Mompower Conference 2023 DeckDocument23 pagesMompower Conference 2023 Deckdeepan sNo ratings yet

- Gf8 - Student ProfileDocument1 pageGf8 - Student ProfileEunice BasarioNo ratings yet

- Courtship and MarriageDocument28 pagesCourtship and MarriageEllie LinaoNo ratings yet

- Condominio Orion em Construção - Sommerschield 2Document15 pagesCondominio Orion em Construção - Sommerschield 2Wendy Cinthia Nobela InácioNo ratings yet

- T1031-Family Law IDocument5 pagesT1031-Family Law IRAJAMRITNo ratings yet

- Eastwest Bank Foreclosed Properties For Sale September 28 2020Document12 pagesEastwest Bank Foreclosed Properties For Sale September 28 2020Kai SanchezNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing - SampleDocument1 pageLegal Writing - SampleMarti Clarabal100% (1)

- Marriage: An Anthropological PerspectiveDocument21 pagesMarriage: An Anthropological PerspectiveKalai VananNo ratings yet

- Aspa SFDocument6 pagesAspa SFEleena100% (3)

- 1st-Family LawDocument25 pages1st-Family LawhazeeNo ratings yet

- Kris AquinoDocument2 pagesKris Aquinoeaguinaldo22No ratings yet

- Sample Therapeutic Separation AgreementDocument2 pagesSample Therapeutic Separation AgreementAlex BascheNo ratings yet

- 1988-1997 Persons BAR Q - ADocument47 pages1988-1997 Persons BAR Q - AAw LapuzNo ratings yet

- Custody NotesDocument2 pagesCustody NotesKevin BarrettNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Worksheet - My Family (Medium)Document2 pagesVocabulary Worksheet - My Family (Medium)Thevin Rainer TedjasukmanaNo ratings yet

- Annulment, Divorce and Legal Separation in The PhilippinesDocument15 pagesAnnulment, Divorce and Legal Separation in The PhilippinesSerene SantosNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Study About The Legalization of Divorce in The PhilippinesDocument61 pagesA Comprehensive Study About The Legalization of Divorce in The PhilippinesHeyward Joseph Ave54% (13)

- Adoption 101Document9 pagesAdoption 101Terrance HeathNo ratings yet

- Families: Materijal Za Učenje Na Daljinu (IV Razred)Document9 pagesFamilies: Materijal Za Učenje Na Daljinu (IV Razred)DJordjeNo ratings yet