Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Collaboration in Business Schools

Uploaded by

Iwan SaputraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Collaboration in Business Schools

Uploaded by

Iwan SaputraCopyright:

Available Formats

J Acad Ethics (2008) 6:715 DOI 10.

1007/s10805-007-9050-8

Collaboration in Business Schools: A Foundation for Community Success

Leland Horn & Michael Kennedy

Published online: 28 November 2007 # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2007

Abstract Business schools are often thought of as being accountable for the individual students personal development and preparation to enter the business community. While true that business schools guide knowledge development, they must also fulfill a social contract with the business community to provide ethical entry-level business professionals. Three stakeholders, students, faculty, and the business community, are involved in developing and strengthening an understanding of ethical behavior and the serious impacts associated with an ethical lapse. This paper discusses the ways the business schools may enhance the students ethical knowledge and understanding, and proposes a roadmap that business schools may use to develop or strengthen a strong ethical culture. Keywords Business community . Business school . Collaborate . Environment . Ethical . Ethical guidelines . Faculty . Ownership . Partnership . Social . Stakeholder . Student

Introduction Business schools and the business community seem to be facing a common threat a growing lack of strong ethical conduct. Corporations are spending significant resources across their organizations to return to the simple foundation that solid ethical behavior provides while business schools are examining how they might improve the focus on ethics. The two primary options are stand alone ethics course instruction and an integrated approach involving ethics scenarios in the core classes. Business schools are likely to increase their success in preparing future business leaders if the academic environment encourages a strong ethical culture among both faculty and students. Although business schools shoulder most of the responsibility for student development, the business

The authors, Leland Horn and Michael Kennedy, are third year doctorate of management students at Colorado Technical University, 4435 North Chestnut Street, Colorado Springs CO 80907.

L. Horn (*) : M. Kennedy Colorado Technical University, 4435 North Chestnut Street, Colorado Springs, CO 80907, USA e-mail: leland.c.horn@boeing.com

DO9050; No of Pages

L. Horn, M. Kennedy

community must play a significant role in the process. Collaboration between each of three stakeholders, students, faculty, and business community, will likely provide mutual benefit to each member and indirectly contribute to a stronger business society. This paper will examine some impacts to each of the stakeholders and provide a roadmap for guiding improvements in ethics education. Situational awareness, business acumen, critical thinking, and personal accountability are key factors in ethical decision making. It is highly probable that graduate-level students enter the business education environment with a pre-existing ethical foundation (Sims and Felton 2006) that may need strengthening during the academic years. These graduate-level foundations are generally established through parenting responsibilities and other life and work experiences. At the undergraduate levels, these foundations may be built or influenced by parents or some recent work experience. This based on the simple thought that as business school freshmen, a majority will experience their first occurrence of living on their own and must base future ethical decisions on earlier lessons learned. Although most college students have been exposed to personal decision making, these ethical beliefs are likely to have not been tested in a rigorous or high-pressure environment where business decisions are made (Sims and Felton 2006). The challenge to business school curricula is one of developing this ability to make ethical decisions whether creating from scratch (the worst case), reshaping, or strengthening (the best case). Fortunately, business schools do not have to go-it-alone in developing an ethics-based curriculum. In 2004 the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) International released a report encouraging curriculum changes that can help students to grow and learn through observation of the ethical culture in their school. This report also provides broad guidance for beginning development of moral courage that will help students understand how to bridge the gap between developing ethical values and applying values when confronted with an ethical dilemma (Phillips 2004). Development of moral courage and with a strong foundation of ethical understanding will do three things for business school graduates. It will provide the student with the understanding that todays well-intentioned decision may have long-term ethically irresponsible results (Sims and Felton 2006). A lapse in moral courage may facilitate short-term behavior rationalization that a particular behavior is okay when in reality it is not okay and may bring serious consequence. Secondly, it will increase the students awareness of the principles of corporate governance and how these principles can be combined with policies, laws, and other regulatory guidance to help deter unethical behavior (Phillips 2004). Finally, an individuals comfort level with discussing ethics application will be improved and result in more open and frank learning opportunities across the student body or employee work force (Sims and Felton 2006). This environment of moral courage should create opportunities for the stakeholders to enjoy ethics minutes where shared experiences can bring true learning to the forefront.

Stakeholders While each group of stakeholders will have unique self-interests as illustrated in Table 1, a common interest should focus on establishing and developing a solid foundation of ethical learning. This foundation will better prepare the student for todays business environment where customers, suppliers, investors, government oversight and special interest groups often bring separate agendas and create ethical minefields. During a February 2007 interview, Dr. Jerry Trapnell, the Executive Vice-President and Chief Accreditation Officer of AACSB, clearly stated the importance of establishing standards that govern and guide

Collaboration in business schools: A foundation for community success Table 1 Stakeholder roles in a collaborative environment Stakeholder Student Role in collaborative environment

Faculty

Business community

Willing and active participants throughout the educational experience, contributors to the development of codes of conduct, collaborative learning, mentoring other students, coowners of the process, committed to success, contributing members of the ethical culture, ethically and socially responsible Responsible for ethical governance of the business school, teachers, guidance counselors, mentors, obligated to other members of the stakeholders group, authors of codes of conduct, ethical leadership, critical to the establishment and success of an ethical culture, committed to success, ethically and socially responsible Partners with business school (faculty and students), provide ethical leadership and experience necessary for individual growth, committed to success, contributors to the development of codes of conduct, ethically and socially responsible, mentors, active participants, recipients of well-developed, ethically experienced students

the student throughout their academic experience. He believes students must become part of the process that develops moral courage in order to become better prepared for future business situations (Trapnell, personal interview, February 28, 2007). Most undergraduate students enter the academic environment believing the institution will provide instruction and guidance to assist them in achieving their objective of professional business employment (Boyle 2004). A proven success story are the military academies that produce graduates with the responsibility, integrity, and ethical foundation that builds moral courage. As a second part of this development, the institution should also expect students to contribute to the development of fellow students and the business school as a whole. The educational experience is heightened when diversity is present, where students from all walks of life share different experiences, opinions, cultures, and expectations. This unwritten social contract for proper education and preparation is based on trust or an expression of faith and confidence that a person or an institution will be fair, reliable, ethical, competent, and non-threatening as defined by Carnevale (1995). The effective social contract should identify the goals and objectives of the business school student and include association with a particular organization in the school or with their current employer (Mowday et al. 1982). Caldwell et al. (2005) proposed that such social contracts should be viewed subjectively based on individual perceptions as viewed through a mediating lens. In describing that mediating lens, Caldwell and Clapham (2002) identified six defining characteristics: 1 Ethically Founded The lens is based upon ones ethical assumptions about the work and how it should operate. 2 Both Cognitive and Affective Perceptions of individuals through their lens incorporates cognitive or rationally determined perceptions and affective or emotionally based perceptions. 3 Contextually Interdependent Context at the organizational and the individual level impact meaning. 4 Goal Directed The lens provides both instrumental and normative clarity incorporating desired outcomes and fundamental values. 5 Systemically Dynamic The lens incorporates feedback systems and information consistent with elements of system theory. 6 Based upon a Five Beliefs Model The lens takes into account ones beliefs about self, other, the past, current reality, and the future. (Caldwell et al. 2005)

10

L. Horn, M. Kennedy

Successful application of this lens will help the student relate any pre-formed ethical thought patterns to their academic performance. In a favorable environment these students may change their pre-conceived ethical thought patterns as they progress through the curriculum to graduation and entry to the work force. As students begin to interact with fellow students, faculty, and guest lecturers, reinforcement of these improving ethical thought patterns will occur. When business schools make ethics a priority and encourage the interchange of ideas on ethical behavior, then students driven by the goal to graduate (goal directed) are more likely to change and improve thoughts that translate into behavior (systemically dynamic). In a final application of a mediating lens, students will combine their pre-conceived ethical beliefs (self) with other beliefs from peers and faculty or instructors as they progress toward graduation. They may likely add past experiences from home, family, or learned from guest speakers and lecturers, and the larger impact of what the future may bring in the form of business challenges, to their moral courage and ethical behavior. In curriculums where professors incorporate ethical conundrums into their course work to stimulate discussion concerning the applicability of the conduct, action, or other training event to ethical behavior, students may also develop or increase moral courage (Karri et al. 2005). This tuned case study approach is the best application for true ethics learning as students can see and feel a direct relationship of ethical behavior and decision making to their study choices. The next group of stakeholders, the business school faculty, must actualize a commitment to the continued development of student ethical behavior by increasing their own accountability. A great classroom goal to set is one of having, or developing, strengthened understanding of proper behavior in the business community. Business schools have a responsibility to the ethical and social development of the student as they prepare to enter society, and Columbia University has already made an attempt to integrate ethics education into their curriculum by inserting ethics sessions into many of their traditional courses (Alsop 2006). This kind of growth may likely remove any stumbling block to future success due to an ethical lapse (Boyle 2004). One interesting observation on why ethics instruction is so often reduced or ignored is that since ethics instruction is not part of the rankings of a school program performance it becomes an easy target for curriculum cost or schedule reductions (Gioia 2002). Gioia also maintains that the recent ethics scandals should be a wake-up call for both schools and businesses to get their house in order. While the reader must make their own decision whether to agree with the premise of a connection between ethics teaching and school rankings, it is important to understand that faculty must accept their responsibility to incorporate ethics teaching at every opportunity. In cases where the student demonstrates disinterest in ethics education, strong mentoring of students by faculty advisors, coupled with ethics-based learning scenarios in foundation courses may help overcome this mindset. Students may not be interested in ethics because they believe it to be outdated or to be a non-essential topic in the learning how to maximize profit approach (Giacalone and Thompson 2006). They conclude that business schools must do three things: have a faculty that is diverse in thinking and ethnic/ gender composition; have doctoral students get a substantive portion of their overall education outside the university preferably in the business sector; and third, train their doctoral students to incorporate ethics and values across their lives, not just in their research or writing (Giacalone and Thompson 2006).This steady diet of ethics teaching, sometimes not even associating the word ethics with the study, will produce a better prepared graduate. The third group of stakeholders is the business community at large. One of the key means to developing the desired community culture of strong ethical behavior is proper

Collaboration in business schools: A foundation for community success

11

governance by management. Managers must be approachable and exhibit proper life values to create a relaxed environment of openness. Only in that environment can employees grow by taking opportunities to speak about ethical behavior, exhibit and live good character, and maintain the corporate responsibilities for honesty and integrity in their actions (Karri et al. 2005). This relaxed learning environment will permit the desired ethical culture to flourish and grow. Focused discussions growing from ethical scandals like Enron and WorldCom are improving the academic and business community awareness of the importance of ethics education. Many companies are now spending resources to contribute to the open environment and cultural growth of their employees by having monthly or quarterly discussions of ethical behavior. These sessions often involve role playing or scenario driven discussions to jump-start the processes of understanding and learning. Business schools have a responsibility to help their students grasp the causal relationship between ethical leadership required to create an environment of trust that yields increasing shareholder value for the growing business (Boyle 2004). At the same time, businesses owe a payback to the schools through participation. Guest lectures, and classroom visits with participation in an ethics driven scenario are but two such application areas. A team approach between business schools and the business community will create a learning environment that will strengthen the students future ability to better perform under stress.

Environment and Culture The foundation of the collaborative ethics learning environment is built upon a partnership of industry and academic leadership that seeks continuous improvement by all three stakeholders, faculty, students and business community (Maurizio 2006). Faculty must be willing to work harder to provide leadership examples for the student while business leaders strive to provide proper behavior examples for their employees and for students when opportunity presents. One of these leadership examples must be a moral person lifestyle, meaning a lifestyle that exhibits an awareness and understanding of multiple stakeholder interests and is always displayed. The second leadership example is one of moral management where the leader has a lifestyle of acceptance of responsibility as an ethical role model (Maurizio 2006). Failure of these two key lifestyles may result in poor leadership in an organization that can create a less open environment for knowledge sharing. This environment is where failing interrelationships between segments of a company or university staff might allow an ethical lapse (Hosmer 1987). When leadership fails to exercise effective control over their departmental implementation of ethical policies and values they allow the development of conditions where cutting a corner or taking a shortcut may be allowed or accepted (Hosmer 1987). If this culture or environment is left unchecked the possibility of an ethical lapse increases. Avoidance of a business ethics lapse or academic cheating scandal requires daily leadership involvement with the details and issues in each academic department, business product team, or business segment (Hosmer 1987). In the business community, the internal corporate pressure to provide high shareholder return can become intense. This pressure can cause the cutting of corners and other perceived small scale unethical behavior to achieve financial goals (Gioia 2002). University departments may suffer from similar issues when faculty leadership fails to maintain focus on ethical behavior, allowing students to have an ethical lapse by succumbing to the pressure to graduate (McCabe et al. 2006). Moral courage is a key requirement to maintaining a strong leadership focus on encouraging ethical behavior to enforce standards though lifestyle example. There are many approaches

12

L. Horn, M. Kennedy

to retaining a focus on ethical behavior, but nothing seems to enjoy success more than the signing of ones name onto a pledge form of some design. Many of todays corporations are turning to the application of an official Code of Conduct for their employees. This is an annual occurrence at The Boeing Company where all employees re-commit to the company behavior standards. While little research exists on an honor code application for graduate students, one suggested approach for a graduate level academic professional code of business conduct is to have students affirm an obligation to act in an ethical manner with honor and integrity in academic performance. Many graduate students are already practicing members of the business community and annually sign business codes of conduct governing their corporate ethical behavior and conduct. Crossing this style and type of behavior from business back into academia would provide familiar, and easily transferred, values and relationships for graduate-level academic behavior and performance (McCabe et al. 2006). Our earlier business example, the Boeing Code of Conduct process states employees will not engage in conduct or activity that may raise questions as to the companys honesty, impartiality, reputation or otherwise cause embarrassment to the company. The code goes on to call out specifically that an employee must not engage in behavior that may create a conflict of interest, bring about inappropriate personal gain, ensure fair dealing with everyone, and protect all assets under their control (The Boeing Company 2007). In his February 2007 interview, Dr. Trapnell indicated his belief that business schools are not doing a very good job articulating and defining ethical conduct within the context of the business education. He believes that having some type of a code of conduct would help reduce the gap between faculty and student perceptions of honest behavior (Trapnell, personal interview, February 28, 2007). Transforming this business code of conduct directly into a graduate academic environment may help grow the culture necessary to improve student body selfenforcement of high academic integrity, ethical behavior, and honesty standards. This type improvement would bring long-term benefit to all the stakeholders. The best, and strongest, codes are built upon a foundation of mutual respect, generated between students and faculty members through clear statements of expected conduct by all involved parties (Coughlan 2005). Key to success is enforcement of the code, and the best enforcement will come from within the governed body where students, or a small council of students, enforce proper behavior on fellow students (McCabe et al. 2006). Our military academies, both federal and state, have long maintained such enforcement with good success. As employees work their daily routines, they operate as a team in an organizational culture founded upon established beliefs and values (Sims and Felton 2006). A strong culture in a relaxed environment encourages collaboration among the team members as they work toward the achievement of common goals and shared success (Maurizio 2006). In many companies, culture provides indirect guidance for ethical behavior and decisionmaking, while the direct, more formal guidance may exist as codes of conduct, or policy and values statements (Coughlan 2005). Leaders within these organizations must act appropriately to create a culture where ethical behavior is encouraged, creating an atmosphere where trust can flourish and grow (Zhu et al. 2004). In an interview conducted by Christine Henle, Terry Broderick, then President and CEO of Royal & SunAlliance USA, made a simple statement that ...a value like truth or trust has a lot of different interpretations. If you are going to build a case for values in a business school curriculum or in a corporation you have to take the time to dialogue about what those things mean and what they look like in practical terms (Henle 2006). The use of live ethics cases in teaching provides adds an element of realism to the learning experience. It also creates an opportunity for improving a foundation for student conceptual understanding and practical

Collaboration in business schools: A foundation for community success

13

application of ethics (McWilliams and Nahavandi 2006). Case studies offer students an opportunity to apply ethical practices gained through the traditional learning experience. If students are required to perform case analysis they can also become immersed in those ethical issues associated with the case to provide ownership of learned ethical beliefs and perceptions (McWilliams and Nahavandi 2006). As discussed earlier, leaders must provide the moral person and moral management lifestyle examples to establish or strengthen an environment of openness. Leading in, and shaping, this open environment can create a strong ethical culture and develop or strengthen the proper values through the creation of trust among team members. LaRue Hosmer defines trust as an expectation of behavior resulting from morally correct decisions and actions where this behavior must place the service of others, or of an organized body, above self-interests (Hosmer 1995). If students are to understand the importance and practical application of ethics, they must be immersed in an ethics-based environment. This environment is best formed when business schools are deeply committed to establishing a culture where ethics is both taught and demonstrated. Business schools should emphasize the importance of creating a culture where ethics becomes pervasive throughout the organization (Alsop 2006). As a result of a favorable environment and open culture, graduates will carry those lessons to their employment environment.

Moving from Theory to Practice The business school environment is bursting with expectations. Students have expectations of the school, the faculty has expectations of the students, and the business community certainly has expectations of a future employee. Every member of the stakeholder group must share responsibility for managing and achieving those expectations. As previously mentioned, the military academies have strongly encouraged (through rigid organizational structures) student participation in the day to day management of the university. Students play a significant role in the development and enforcement of honor codes and/or codes of conduct. For example, seniors (first class cadets) at the United States Air Force Academy manage the student body honor education program under academy staff oversight (Bailey 1999). Perhaps an abbreviated version of the military academy structure/program would be useful in developing and fostering a mindset focused on developing and strengthening a strong ethical and social culture. For this culture to be successful the stakeholders must take a participatory role in the process to develop or feel ownership. Expectations must be clearly defined (codes of conduct/standards) and procedures (effect) identified to address any enforcement aspect of the process. Failing to enforce standards greatly reduces confidence in the process leading to diminished stakeholder participation and ultimately failure or collapse of the process. Figure 1 illustrates one possible recommendation for constructing a framework we call the Community Collaboration Board (CCB). The CCB could be useful in developing and strengthening a strong ethical and social culture by the stakeholders. Much like the military academies, in this framework the students will take leadership roles. Internally to the business school the faculty provides the necessary oversight while externally the business community plays a partnership role with both faculty and students. The faculty and business community become teachers and mentors to the students to coach in both leadership and ethical behavior. Each student class has representation on the Student Ethics Board (SEB) and they act as conduits between their fellow classmates and the SEB. The members of the Student Board of Directors are elected by their classmates and oversee the process of annually reviewing the academic code of

14 Fig. 1 Community collaboration board

L. Horn, M. Kennedy

conduct. Election of new members should occur on an annual basis and include the Student Chief Executive Officer as a representative from the senior class who leads the group. The framework of the CCB fosters ownership of the process and could likely contribute to an acceptance and acknowledgement of individual responsibility by all stakeholders. Although the development of codes of conduct will certainly contribute to a developing and strengthening a strong ethical and social culture, it is but one part of the process. Stakeholders must become the culture they must live, discuss, mentor, learn, teach, coach, and collaborate, on all social and ethical issues. Many ethics training programs take the form of providing a checklist approach for solving ethical issues by asking questions such as Is it legal? but ultimately culminate in the decision maker facing the issue of how they will live with the decision (Harrington 1991). A better approach is one that will expand upon the tacit knowledge gained through the life and work experience of moving up the corporate ladder or through the academic ranks. Tacit knowledge is believed to be a key component of wisdom and cannot be taught in a classroom setting like a classical academic subject. This knowledge is generally transferred, or learned, through social interaction and experience best gained in those settings where group discussions of ethical behavior and definition happen (Moberg 2006). Since ethics learning issues are often situational, there is no checklist or best answer for each one.

Conclusion Business school graduates face a complex and dynamic business environment that moves at lightning speed where each graduate seeks success. If business school students are to succeed they must possess a strong foundation based on growth and continuous improvement of their ethical beliefs in order to make a positive contribution to society. In this environment, business schools have a responsibility to ensure students receive the tools required to build that foundation (Boyle 2004). This paper presented a framework that incorporates opportunities for students to learn ethical leadership practices that can become

Collaboration in business schools: A foundation for community success

15

cornerstones of the establishment of that foundation: individual growth, institutional growth, shared success, and most importantly a strong ethical and social culture. Independently, each cornerstone is important, but together they provide the framework the student, business school, and business community need to achieve continual success. The authors postulate that the CCB approach will enhance improvement opportunity for stakeholder success. Although research seems to support this theory, a programmatic research project is required to collect and analyze the data necessary to prove the theory. In closing, ethical behavior is an individual responsibility that should not be taken lightly and the business school environment provides tremendous opportunity for improvement.

References

Alsop, R. J. (2006). Business ethics education in business schools: A commentary. Journal of Management Education, 30(1), 1114. Bailey, T. (1999). Its all about character. Airman, (May) 3233. Boyle, M.-E. (2004). Walking our talk: Business schools, legitimacy, and citizenship. Business and Society, 43(1), 137. Caldwell, C., & Clapham, S. (2002). The mediating lens and its multiple applications. Paper presented at the Ninth International Conference Promoting Ethics in Business, Niagara University, October 2002. Caldwell, C., Karri, R., & Matula, T. (2005). Practicing what we teach ethical considerations for business schools. Journal of Academic Ethics, 3(1), 125. Carnevale, D. G. (1995). Trustworthy government: Leadership and management strategies for building trust and high performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Coughlan, R. (2005). Codes, values and justifications in the ethical decision-making process. Journal of Business Ethics, 59, 4553. Giacalone, R. A., & Thompson, K. R. (2006). Business ethics and social responsibility education: Shifting the worldview. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 266277. Gioia, D. A. (2002). Business educations role in the crisis of corporate confidence. Academy of Management Executive, 16(3), 142144. Harrington, S. J. (1991). What corporate America is teaching about ethics. Academy of Management Executive, 5(1), 2130. Henle, C. H. (2006). Bad apples or bad barrels? A former CEO discusses the interplay of person and situation with implications for business education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 346355. Hosmer, L. T. (1987). The institutionalization of unethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 6(6), 439447. Hosmer, L. T. (1995). Trust: The connecting link between organizational theory and philosophical ethics. Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 379403. Karri, R., Caldwell, C., Antonacopoulou, E. P., & Naegle, D. (2005). Building trust in business schools through ethical governance. Journal of Academic Ethics, 3(24), 159182. Maurizio, A. (2006). Business and business schools: A partnership for the future. Tampa, FL: AACSB International. McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Academic dishonesty in graduate business programs: Prevalence, causes, and proposed action. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 294305. McWilliams, V., & Nahavandi, A. (2006). Using live cases to teach ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(4), 421433. Moberg, D. J. (2006). Best intention, worst results: Grounding ethics students in the realities of organizational context. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 307316. Mowday, R. T., Porter, R. W., & Steers, R. M. (1982). Employeeorganization linkages. New York: Academic Press. Phillips, S. M. (2004). Ethics education in business schools. St. Louis, MO: AACSB International. Sims, R. R., & Felton, E. L., Jr. (2006). Designing and delivering business ethics teaching and learning. Journal of Business Ethics, 63, 297312. The Boeing Company (2007). Code of conduct. http://www.boeing.com/companyoffices/aboutus/ethics/ code_of_conduct.pdf. Accessed 3 Feb 2007. Zhu, W., May, D. R., & Avolio, B. J. (2004). The impact of ethical leadership behavior on employee outcomes: The roles of psychological empowerment and authenticity. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11(1), 1626.

You might also like

- The Beginning of The End For Chimpanzee ExperimentsDocument14 pagesThe Beginning of The End For Chimpanzee ExperimentsIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Assisted Reproductive Technologies and The HIV - Infected WomanDocument8 pagesThe Ethics of Assisted Reproductive Technologies and The HIV - Infected WomanIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Value Dissonance and Ethics Failure in AcademiaDocument16 pagesValue Dissonance and Ethics Failure in AcademiaIwan Saputra100% (1)

- The Art of Rhetoric As Self-DisciplineDocument23 pagesThe Art of Rhetoric As Self-DisciplineIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Therapists As Patients - A National Survey of Psychologists' Experiences, Problems, and BeliefsDocument25 pagesTherapists As Patients - A National Survey of Psychologists' Experiences, Problems, and BeliefsIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Workplace and Policy EthicsDocument7 pagesWorkplace and Policy EthicsIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- The Anatomy of SorrowDocument8 pagesThe Anatomy of SorrowIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Using Creative Writing Techniques To Enhance The CaseDocument18 pagesUsing Creative Writing Techniques To Enhance The CaseIwan Saputra100% (1)

- EthicsDocument7 pagesEthicsIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Prior Therapist-Patient Sexual Involvement Among Patients Seen by PsychologistsDocument16 pagesPrior Therapist-Patient Sexual Involvement Among Patients Seen by PsychologistsIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Health Research and The IRBDocument5 pagesQualitative Health Research and The IRBIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- The Ethical Management of A Psychiatric Patient Disposition in The Emergency DepartmentDocument8 pagesThe Ethical Management of A Psychiatric Patient Disposition in The Emergency DepartmentIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Job Opportunities For Special Needs Population in MalaysiaDocument9 pagesJob Opportunities For Special Needs Population in MalaysiaIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Public Service Ethics in The New MillenniumDocument8 pagesPublic Service Ethics in The New MillenniumIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- The Competency Profile of Ethics PractitionersDocument14 pagesThe Competency Profile of Ethics PractitionersIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Responding To Suicidal RiskDocument5 pagesResponding To Suicidal RiskIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Developing HRM Students' Managerial Potential: Uum's Approach To Knowledge ManagementDocument21 pagesDeveloping HRM Students' Managerial Potential: Uum's Approach To Knowledge ManagementIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Interest Policies at Canadian UniversitiesDocument12 pagesConflict of Interest Policies at Canadian UniversitiesIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Islam, Jihad, and TerrorismDocument17 pagesIslam, Jihad, and TerrorismIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Genesis of An Academic Research ProgramDocument9 pagesGenesis of An Academic Research ProgramIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- LaptopDocument39 pagesLaptopArvy DadiosNo ratings yet

- Environmental EthicsDocument5 pagesEnvironmental EthicsIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- A Study of Total Quality Management Implementation in Medan Manufacturing IndustriesDocument37 pagesA Study of Total Quality Management Implementation in Medan Manufacturing IndustriessowmyabpNo ratings yet

- Ethical Antecedents of Cheating IntentionsDocument16 pagesEthical Antecedents of Cheating IntentionsIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Environmental EthicsDocument26 pagesEnvironmental EthicsIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- People Get Emotional AboutDocument23 pagesPeople Get Emotional AboutIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Science and Religion in The Context of Science EducationDocument41 pagesScience and Religion in The Context of Science EducationIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Digital Divide 2.0: "Generation M" and Online Social Networking Sites in The Composition ClassroomDocument8 pagesDigital Divide 2.0: "Generation M" and Online Social Networking Sites in The Composition ClassroomFatimah Munirah Abu BakarNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations For Conducting Cancer Medical StudiesDocument10 pagesEthical Considerations For Conducting Cancer Medical StudiesIwan SaputraNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Independent Study of Middletown Police DepartmentDocument96 pagesIndependent Study of Middletown Police DepartmentBarbara MillerNo ratings yet

- Edition 100Document30 pagesEdition 100Tockington Manor SchoolNo ratings yet

- Education: Address: Mansoura, EL Dakhelia, Egypt EmailDocument3 pagesEducation: Address: Mansoura, EL Dakhelia, Egypt Emailmohammed sallemNo ratings yet

- Classen 2012 - Rural Space in The Middle Ages and Early Modern Age-De Gruyter (2012)Document932 pagesClassen 2012 - Rural Space in The Middle Ages and Early Modern Age-De Gruyter (2012)maletrejoNo ratings yet

- Economic Impact of Tourism in Greater Palm Springs 2023 CLIENT FINALDocument15 pagesEconomic Impact of Tourism in Greater Palm Springs 2023 CLIENT FINALJEAN MICHEL ALONZEAUNo ratings yet

- Labov-DIFUSÃO - Resolving The Neogrammarian ControversyDocument43 pagesLabov-DIFUSÃO - Resolving The Neogrammarian ControversyGermana RodriguesNo ratings yet

- HRM in A Dynamic Environment: Decenzo and Robbins HRM 7Th Edition 1Document33 pagesHRM in A Dynamic Environment: Decenzo and Robbins HRM 7Th Edition 1Amira HosnyNo ratings yet

- Maternity and Newborn MedicationsDocument38 pagesMaternity and Newborn MedicationsJaypee Fabros EdraNo ratings yet

- R19 MPMC Lab Manual SVEC-Revanth-III-IIDocument135 pagesR19 MPMC Lab Manual SVEC-Revanth-III-IIDarshan BysaniNo ratings yet

- Tong RBD3 SheetDocument4 pagesTong RBD3 SheetAshish GiriNo ratings yet

- Step-By-Step Guide To Essay WritingDocument14 pagesStep-By-Step Guide To Essay WritingKelpie Alejandria De OzNo ratings yet

- Art 1780280905 PDFDocument8 pagesArt 1780280905 PDFIesna NaNo ratings yet

- Battery Genset Usage 06-08pelj0910Document4 pagesBattery Genset Usage 06-08pelj0910b400013No ratings yet

- Settlement of Piled Foundations Using Equivalent Raft ApproachDocument17 pagesSettlement of Piled Foundations Using Equivalent Raft ApproachSebastian DraghiciNo ratings yet

- Tax Q and A 1Document2 pagesTax Q and A 1Marivie UyNo ratings yet

- Toolkit:ALLCLEAR - SKYbrary Aviation SafetyDocument3 pagesToolkit:ALLCLEAR - SKYbrary Aviation Safetybhartisingh0812No ratings yet

- NBPME Part II 2008 Practice Tests 1-3Document49 pagesNBPME Part II 2008 Practice Tests 1-3Vinay Matai50% (2)

- 2013 Gerber CatalogDocument84 pages2013 Gerber CatalogMario LopezNo ratings yet

- Developing An Instructional Plan in ArtDocument12 pagesDeveloping An Instructional Plan in ArtEunice FernandezNo ratings yet

- Data FinalDocument4 pagesData FinalDmitry BolgarinNo ratings yet

- 5 6107116501871886934Document38 pages5 6107116501871886934Harsha VardhanNo ratings yet

- Sri Lanka Wildlife and Cultural TourDocument9 pagesSri Lanka Wildlife and Cultural TourRosa PaglioneNo ratings yet

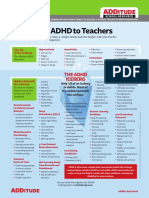

- Explaining ADHD To TeachersDocument1 pageExplaining ADHD To TeachersChris100% (2)

- Organisation Study of KAMCODocument62 pagesOrganisation Study of KAMCORobin Thomas100% (11)

- Episode 8Document11 pagesEpisode 8annieguillermaNo ratings yet

- Sound! Euphonium (Light Novel)Document177 pagesSound! Euphonium (Light Novel)Uwam AnggoroNo ratings yet

- Unit I. Phraseology As A Science 1. Main Terms of Phraseology 1. Study The Information About The Main Terms of PhraseologyDocument8 pagesUnit I. Phraseology As A Science 1. Main Terms of Phraseology 1. Study The Information About The Main Terms of PhraseologyIuliana IgnatNo ratings yet

- Sangam ReportDocument37 pagesSangam ReportSagar ShriNo ratings yet

- 11th AccountancyDocument13 pages11th AccountancyNarendar KumarNo ratings yet

- What Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonDocument7 pagesWhat Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonMichael VladislavNo ratings yet