Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Using Whiteness As A Theoretical Framework

Uploaded by

api-240376720Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Using Whiteness As A Theoretical Framework

Uploaded by

api-240376720Copyright:

Available Formats

Research Essay

Whiteness in Schools

Justin Schultz 2083266

Using whiteness as a theoretical framework, discuss how white cultural norms are systematically enforced in schools. In your response make reference to how the deconstruction of whiteness in Australia better positions teachers to understand why prevailing pedagogical and curricular patterns may not work for Indigenous students?

Michael Omi (Sleeter & McLaren, 1995) states that in our society, one of the first things we notice about people when we encounter them (along with their sex/gender) is their race. We utilize race to provide us with clues about who a person is and how we should relate to her/him. Our perception of race determines our presentation of self, distinctions in status, and appropriate modes of conduct in daily and institutional life. This process is often unconscious; we tend to operate off an unexamined set of racial beliefs (p. 105). If this is true then not only educators, but all members of society must become concerned about the dominance of mainstream white culture in terms of the organisation of perceptions in respect to racial difference (Sleeter & McLaren, 1995, p 105). It must be recognised that the ideology of white supremacy undergirds many of the assumptions and ideas of the white mainstream culture (p. 105). Furthermore, Omi (Sleeter & McLaren, 1995, p 105) states that the popular culture of the white mainstream governs the signs, symbols, concepts and images through which we understand, interpret and represent what he refers to as racial difference. This dominant mainstream white culture plays a pivotal role in the formation of our cultural identities and therefore how we see ourselves in relationship to others (Sleeter & McLaren, 1995, p 105). To reaffirm this, Haymes (1995, p. 106) states that white supremacist assumptions and ideas about race are enabled to penetrate every facet of daily life, suggesting that close attention must be paid to how educators, students, and communities interpret racial difference, particularly in the context of popular culture. When considering notions of race, multiculturalism and reconciliation in both the education system and in the wider communities, it is important to contemplate the fact that the organisations responsible for the creation and implementation of not only government policies, but also smaller multicultural and reconciliation strategies that affect Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians would most likely be staffed and administrated by a majority of middle-class white people (Haymes, 1995, p 106). This may very well have an effect on the goals, orientation and success of such strategies. Furthermore, if reconciliation and a just society is to be achieved, the general white population first need to realise and be constantly aware of how non-white cultures have become the markers of racial difference and that because of this, and as a result of a white mainstream approach to multiculturalism, whiteness has become deracialised and normalised and that peoples of other races have become racialised and othered; thus causing racism to become no longer a problem for the white mainstream society, but an issue for the minority to deal with; and this is in no way the way it should be (Haymes, 1995, p. 107). Pre-service teacher interviewees in Hickling-Hudson (2005) express how they were made involuntary participants of institutional racism in their schooling experiences; referring predominantly to the tokenistic fashion that their schools represented and explained ideas such as multiculturalism and how covertly racist material was masqueraded as neutral and impartial (p. 344). Assimilationist methods were also often highlighted as well as an awareness of the contradiction and tension between the rejection of overt racism and the perpetuation of everyday white privilege (Hickling-Hudson, 2005, p. 345). Both the curriculum and

1

Research Essay

Whiteness in Schools

Justin Schultz 2083266

particular celebrations that some of the students from Hickling-Hudsons (2005) interviews experienced created a space where Indigenous students were externalised and made outsiders in their own country (p. 346). This is just a few examples of how schools, as a collective institution, promote and reproduce cultural norms and inflict systemic racism on Indigenous students. Torok (2007) also explains how curriculum in schools is heavily influenced by the political issues at the time. This influence reflects and reproduces hegemony and the values of those in power covertly through the use of ideologies, meanings and daily practices and ignores the values of minority groups, such as the Aboriginal peoples of Australia (p. 70). Torok (2007) goes on to explain how schools are one of the primary institutions for reproducing inequalities and social norms that are designed to serve the interests of the dominant class in power and that this hierarchy oppresses those classed as who do not necessarily share those particular values (p. 71). The hidden curriculum (p.73) that reinforces and reproduces social norms in the classroom is achieved through the inclusion and exclusion of information in the curriculum. The selection of information is scrutinised by the privileged classes with their own purposes in mind (p. 72). A link can be made here to the inclusion/exclusion of particular facts offered when explaining Australian history and the invasion and colonisation of the Indigenous Australians. The perspective o the white colonisers could be presented to the class as opposed to the real facts of the horrors that were inflicted on the Indigenous peoples of Australia. Despite the difficulties faced by teachers to become transformative and experiment in socially just, risk taking pedagogies, there are some initiatives, such as the Innovative Design for Enhancing Achievements in Schools (IDEAS) project that was started in Southern Queensland in 1998 and was trialled nationally in 2002. Initiatives such as this challenge the hegemony of dominant cultures and systems that repress disadvantaged groups with transformative ideas in action (Torok, 2007, p. 77). This can be achieved by creating more culturally sensitive curriculum and promoting a greater sense of identity, knowledge and inclusion of students as well as breaking down barriers between families and the institution (p.78) Many of the views expressed by interviewees in Burridges (2008) study illustrate that although education is a key factor in achieving an equal and socially just society, it must be understood that reconciliation cant be taught to students. Educators need to provide the necessary tools such as deep critical thinking, introspective evaluation, and investigative processes and above all, uncensored factual history so that the students can decide for themselves what reconciliation and equality mean to them. A quote from Burridges (2008) study sums up this notion: All you can do is give people the information and let them form their own opinions. It must be education, not indoctrination. Reconciliation is founded on education but cant be achieved solely this way (p. 15). Haymes (1995) explains that critical educators must also be aware of the ways in which outlets governed by a white mainstream agenda in popular culture continue to shape the categories of racial meaning that students use to construct their interpretations of their experiences. These categories are not static and are constantly re-evaluated and reformed, so close attention must be allowed as to recognise the overt and covert racism present in contemporary popular culture. This is so important because the experiences and interpretations of students prefigure how they produce and respond to classroom knowledge and this has the power to reproduce racially negative social norms and trends. One way of creating and maintaining this awareness could be to use popular culture as an object of critical study in the classroom when investigating individual experience (p. 106).

2

Research Essay

Whiteness in Schools

Justin Schultz 2083266

Educators must also confront and critically analyse how the racial meaning systems found within contexts such as popular culture also shape them as racial subjects and consequently evaluate how they think about and do multicultural education within this framework (106). In so doing, educators take an inward approach and examine themselves and their own identities. Haymes (1995) suggests that teachers can confront their own racial formation as well as that of their students by realising the significance of the white cultures control over social and electronic media and how popular culture is constructed around a politics of difference or politics of diversity (p. 107). Furthermore, Coghlan (2001) has a more outward and direct approach which suggests that teachers should attempt to teach about racism and its origins and forms by teaching students about nationalism, power, and conflict, as well as gender, race and class in relation to, and in the context of, imperialism, colonialism, jingoism and the notion of civilisation. This use of history places racist attitudes in a time or era context, where ideas are fashioned and influence by popular theories of the time. One aim of this could be to associate the contradictory and incorrect notions of race with the now disproven and sometimes absurd theories of that time. Bedard, (1999), Coghlan (2001), Connelly (2002), Haymes (1995), McLaren (1994) and Tannoch-Bland (1997) all highlight and discuss that one main issue with a white mainstream approach to multiculturalism and multiculturalism in education is the invisibility of the over-arching concept of whiteness, and more importantly and the invisibility of the unearned and systemic privileges associated with whiteness. Furthermore, because of this transparency, racism has become a problem for the Indigenous people of Australia and not for white Australians; it exists in the system outside us, impacting on others but not us (Tannoch-Bland, 1997, p.1). The difficulty (and contradictory position) of white teachers internalising and implementing anti-racist education in schools is due to the fact that racism and institutional racism are so imbedded into what it is to be white Bedard, 1999, p. 2). The colonial, imperialistic and capitalistic history that defines white mainstream identity is so ingrained and so invisible that it seems impossible for anti-racist education to be effectively carried out or even considered without a decolonising process of the self to be achieved prior to teaching (Bedard, 1997). Connelly, (2002) in particular, highlights the need to move beyond the essayist and arbitrary examinations of whiteness that are discussed and explored in journals and sometimes portrayed in the media and more closely look at the effects of such a concept in the classroom environment. The self-reflective and internal exploration of whiteness and what this means is required by educators because without a deep understanding of such efforts, how can they promote it to students? Both Connelly (2002) and Bedard (1999) conclude that the benefits of such a decolonising process hold many advantages that could be directly transferred to and evaluated by students. On top of this decolonising process more initiatives such as the IDEAS project need to be activated around the nation to re-evaluate and critically analyse the social norms reproduced in our classrooms and challenge those that are not culturally sensitive and inclusive of all students.

Research Essay

Whiteness in Schools

Justin Schultz 2083266

Research Essay

Whiteness in Schools

Justin Schultz 2083266

Reference List Bedard, G., (1999), Deconstructing Whiteness: Pedagogical implications for Anti-Racism Education, National Library of Canada, Canada *Although speaking from a Canadian perspective, Bedards ideas and suggestions of and for racism and the need for decolonising teachers in schools are very relevant to the situation we face in Australia. Burridge, N., (2008), Unfinished business: re-igniting the discussion on the role of education in the reconciliation process, presented at Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) Conference, November 27th, 2007, Fremantle Coghlan, M., (2001), Racism: ideasfortheclassroom,Agora, v.36, n.4, pp. 16-18 Connelly, J., (2002), Investigating Whiteness: whiteness processes: enigma or reality disguise? viewed 11 October, 2011, <www.aare.edu.au/02pap/con02196.htm>. pp. 1-19. Haymes, S. N., in (1995), Multicultural Education, Critical Pedagogy, and the Politics of Difference, ed. Sleeter, C & McLaren, P., State University of New York Press, Albany Hickling-Hudson, A., (2005), White, Ethnic and Indigenous: pre-service teachers reflect on discourses of ethnicity in Australian culture, Policy Futures in Education, vol. 3, no. 4, [online] doi: 10.2304/pfie.2005.3.4.340 McLaren, P., (1994), Life in Schools: An introduction to critical pedagogy in the foundations of education, second edition, Longman, New York

Tannoch-Bland, J., (1997), Identifying White Race Privilege, viewed 11 October, 2011, <www.mailarchive.com/recoznet@paradigm4.com.au/msg02617.htm>. pp. 1-4. Torok, R., (2007), The Re-historicisation and Increased Contextualisation of Curriculum and Its Associated Pedagogies, International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 67-81. September 2007

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Oxford Drawing Book 1852Document234 pagesThe Oxford Drawing Book 1852lotusfrog100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 0620 w17 Ms 21 PDFDocument3 pages0620 w17 Ms 21 PDFyuke kristinaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- General Certificate of Education Syllabus Ordinary Level HISTORY (WORLD AFFAIRS, 1917-1991) 2158 For Examination in June and November 2011Document7 pagesGeneral Certificate of Education Syllabus Ordinary Level HISTORY (WORLD AFFAIRS, 1917-1991) 2158 For Examination in June and November 2011mstudy123456No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Teaching Profession Chen26Document42 pagesTeaching Profession Chen26Roman SarmientoNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Poster Design-Unit PlanDocument2 pagesPoster Design-Unit Planapi-264766686No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Teacher S Book B1Document26 pagesTeacher S Book B1Hamilton Pulgarin Correa53% (15)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Lesson Plan Form CSUDH Teacher Education DepartmentDocument6 pagesLesson Plan Form CSUDH Teacher Education Departmentapi-285433730No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- SIP Annex 1A School Community Data Template 10302015Document17 pagesSIP Annex 1A School Community Data Template 10302015Jessamarie Sugano AbordoNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Practice of Sight Words Using PoetryDocument6 pagesPractice of Sight Words Using PoetryAnonymous q7WOXGrSNo ratings yet

- DLPDocument2 pagesDLPEunice Junio NamionNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Personal Narrative Unit UBDDocument26 pagesPersonal Narrative Unit UBDLindsay Nowaczyk100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Situational Analysis On Access Sip 2015Document8 pagesSituational Analysis On Access Sip 2015LeonorBagnison100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Poem Summary - An Elementary School Classroom in A SlumDocument2 pagesPoem Summary - An Elementary School Classroom in A SlumVikash Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Lesson Exemplar in MAPEH 6 Using The IDEA Instructional ProcessDocument2 pagesLesson Exemplar in MAPEH 6 Using The IDEA Instructional ProcessRonald Bautista Albo100% (3)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Edu 541 Assignment 3Document6 pagesEdu 541 Assignment 3api-280375586No ratings yet

- Emmanuella's CV (Modified)Document2 pagesEmmanuella's CV (Modified)Emmanuella NduonofitNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Activity Design For Brigada EskwelaDocument2 pagesActivity Design For Brigada Eskwelagene100% (3)

- Phonics DeckDocument91 pagesPhonics Deckmsherilyn78No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Maths - SA-1 - Class XDocument74 pagesMaths - SA-1 - Class XVarunSahuNo ratings yet

- 1954 YearbookDocument32 pages1954 YearbookHarbor Springs Area Historical SocietyNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesA Detailed Lesson PlanJee Han100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Literacy NarrativeDocument3 pagesLiteracy Narrativethat_skyler_girlNo ratings yet

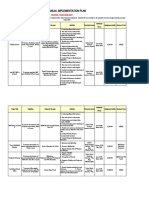

- Annual Implementation Plan: SCHOOL YEAR 2020-2021Document6 pagesAnnual Implementation Plan: SCHOOL YEAR 2020-2021Ian Rey Mahipos SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Eld Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesEld Lesson Planapi-307224989No ratings yet

- Group Forum 1 What Is Professional Development and What Are Some Professional Development Activities That Will Benefit TeachersDocument10 pagesGroup Forum 1 What Is Professional Development and What Are Some Professional Development Activities That Will Benefit TeachersRuth LingNo ratings yet

- Word WallDocument1 pageWord Wallapi-339264121No ratings yet

- RPH Bi - KM PKDocument7 pagesRPH Bi - KM PKatikah aziz96No ratings yet

- Appendix C: Pre - Service Teacher's Actual Teaching Observation and Rating SheetDocument2 pagesAppendix C: Pre - Service Teacher's Actual Teaching Observation and Rating SheetRubs ADNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Harshbarger Resume 2015Document2 pagesHarshbarger Resume 2015api-298548905No ratings yet

- Araling PanlipunanDocument14 pagesAraling Panlipunananna lissa t seloterio0% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)