Professional Documents

Culture Documents

67 1351430663

Uploaded by

Chintya Permata SariOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

67 1351430663

Uploaded by

Chintya Permata SariCopyright:

Available Formats

Hiren Parmar et al.

Recent Trends in Peptic Perforation

RESEARCH ARTICLE

RECENT TRENDS IN PEPTIC PERFORATION

Hiren Parmar, Moolchand Prajapati, Rashmikant Shah Smt NHL Municipal Medical College, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India Correspondence to: Hiren Parmar (drhirenparmar@gmail.com) DOI: 10.5455/ijmsph.2013.2.110-112 Received Date: 28.10.2012 Accepted Date: 28.10.2012

ABSTRACT

Background: The peptic perforation is one of the commonest abdominal surgical emergencies. Common causes are H.pylori, increased inadvertent use of NSAIDS, smoking and stress of modern life. During last few years there has been great revolution in availability of the newer broad spectrum antibiotics, better understanding of disease, effective resuscitation, prompt surgery under modern anaesthesia techniques, and intensive care unit resulted in reducing the mortality. Aims & Objective: To study the recent trends in peptic perforation. Material and Methods: This prospective study was carried out in the department of surgery during period from 1st May 2009 to 30th November 2011. All were indoor patients with diagnosis of peptic perforation in stomach and/or duodenum excluding other sites. Each patient was study in detail with relevant clinical history, examination, laboratory investigations and management. The study comprised of total 50 patients operated for peptic perforation by various modalities. Results: The middle age group was commonest. Smoking, alcohol and stress were common etiological factors. The perforation was common in anterior surface of the first part of duodenum. Wound infection and bronchopneumonia were common post-operative complications. Conclusion: The duration of perforation more than 24 hours and size of the perforation more than 1 cm has increase morbidity & mortality. Early diagnosis and prompt management of shock & septicaemia is important for better prognosis of patients. The simple closure with omentopexy of peptic perforation still remains the first choice as a treatment. H-pylori eradication treatment is mandatory after simple closure of the perforation to prevent recurrence of ulcer.

KEY-WORDS: Peptic Perforation; Etiological Factors; Emergency Surgeries; H. pylori Treatment

Introduction

The perforation of stomach & duodenal ulcer is one of the commonest abdominal surgical emergencies. One specific etiological agent cannot be incriminated in the causation of this particular disease. Common causes[1] are H. pylori, increased inadvertent use of NSAIDS, smoking and stress of modern life. During last few years there has been great revolution in availability of the newer broad spectrum antibiotics, better understanding of disease, effective resuscitation, prompt surgery under modern anaesthesia techniques, and intensive care unit resulted in reducing the mortality.[2] The aims & objectives of this study are (1) to study predisposing factors and incidence for peptic ulcer disease and peptic perforation (2) to study etiopathogenesis of it (3)

110

to study patient presentation and manifestation (4) to study management of acute presentation of peptic perforation patients (5) to study various modalities of treatment (6) to study postoperative complication in operated cases of peptic perforation.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study was carried out in the department of surgery during period from 1st May 2009 to 30th November 2011. All were indoor patients with diagnosis of peptic perforation in stomach and/or duodenum excluding other sites. Each patient was study in detail with relevant clinical history, examination, laboratory investigations and management. The study comprised of total 50 patients operated for peptic

International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health | 2013 | Vol 2 | Issue 1

Hiren Parmar et al. Recent Trends in Peptic Perforation

perforation by various modalities. The selection criterions for the patient were (1) complain of upper abdominal pain (2) on examination- severe epigastric tenderness (3) X-ray- free gas under dome of diaphragm (4) Ultrasonography of abdomen mild to moderate free fluid either in pelvis or Morrison pouch (5) per-operative finding- peptic perforation in stomach and/or duodenum. The selected patients had been operated thereafter in form of different modalities like, (a) simple closure with omental graft[3] (b) definitive surgery with simple closure (c) laparoscopic closure[4]. The definitive surgery with simple closure includes simple closure + gastrojejunostomy + vagotomy, simple closure + gastrojejunostomy, simple closure + partial gastrectomy, simple closure + antrectomy + agotomy and simple closure + pyloroplasty + vagotomy. All the patients were observed postoperatively for complications like, paralytic ileus, pulmonary complications, wound infection, septicaemia etc. All the patients were received anti H. pylori treatment[5] post-operatively.

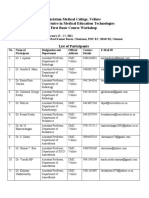

Table-2: Occupation Incidence Occupation No. of cases Labour/ Executive 32 Farmer 3 House-wife 6 Student 3 Retired 6 Table-3: Relation with Smoking and Alcohol History of smoking and/or alcohol No. of cases Present 37 Absent 13 Table-4: Symptoms of Perforation Symptoms No. of cases Pain in abdomen 50 Nausea & vomiting 47 Fever 21 Distension of abdomen 05 Table-5: Site of Perforation Site of Perforation First part of duodenum in anterior wall Pyloric antrum in anterior wall, body of stomach near lesser curvature in anterior wall No. of cases 41 09

Results

The commonest age group was from 41-60 years which reflect the correlation between age and etiological factors (Table 1). Due to stress and bad habits, the incidence was common in labours and executives (Table 2). Smoking and alcohol are commonest etiological factors as it was present in 76% of patients (Table 3). In the case of peptic perforation, pain in abdomen is the commonest symptom (Table 4). In 82% of patients, the perforation was in the anterior wall of the first part of duodenum (Table 5). The wound infection and bronchopneumonia were common postoperative complications. All patients were presented with acute peritonitis and operated in emergency which may lead to such complications (Table 6).

Table-1: Age Incidence Age ( in years) 1-10 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 > 60 No. of cases 0 2 8 8 14 10 8

Table-6: Post-Operative Complications Post-Operative Complications No. of cases Bronchopneumonia 8 Wound infection 6 Fever 5 Paralytic ileus 1 Intraperitoneal infection ( pelvic abscess ) 0 Reexploration 0 Death 2

Discussion

The data were derived from the study of 50 cases of peptic perforation operated in emergency and compared with other studies. The highest incidence of peptic perforation was observed in 5th decade of life, which is a peak active period. This may be due to stress & strain during that period.[6,7] The perforation was more common in male compared with female because of more association with smoking & alcohol.[8] It was noticed that perforation occurred in the patients belonging to poor socioeconomically class[9], who are manual workers (unskilled workers). Out of 50, 37 patients had a history of smoking and/or alcoholism. It showed that incidence is more in smokers & alcoholics.[10] Large group of patients were presented to hospital within 6 hours in which the prognosis was excellent.[11,23] Pain was the main presenting symptom in all the cases with

111

International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health | 2013 | Vol 2 | Issue 1

Hiren Parmar et al. Recent Trends in Peptic Perforation

mainly acute onset.[12] The commonest site of the perforation was at anterior wall of the first part of duodenum.[13] The outcome of simple closure with omental graft was excellent as compared with definitive surgery.[14] Most common postoperative complication was bronchopneumonia followed by wound infection. Two patients were died within 96 hours of post-operative period. These patients were presented with severe shock and septicaemia and died because of multiorgan failure.[15] All remaining 48 patients were advised anti H. pylori treatment with omeprazole, amoxicillin and metronidazole for two weeks, followed by proton pump inhibitor for four weeks.[16]

Conclusion

The duration of perforation more than 24 hours[17] and size of the perforation more than 1 cm[18] has increase morbidity & mortality. Early diagnosis and prompt management of shock & septicaemia is important for better prognosis of patients.[19] The simple closure with omentopexy of peptic perforation still remains the first choice as a treatment.[3] H-pylori eradication treatment is mandatory after simple closure of the perforation to prevent recurrence of ulcer.[21]

References

1. Torab FC, Amer M, Abu-Zidan FM, Branicki FJ. Perforated peptic ulcer: different ethnic, climatic and fasting risk factors for morbidity in Al-ain medical district, United Arab Emirates. Asian J Surg 2009;32:95101. 2. Aga H, Readhead D, Maccoll G, Thompson A. Fall in peptic ulcer mortality associated with increased consultant input, prompt surgery and use of high dependency care identified through peer-review audit. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000271. 3. Nuhu A, Madziga AG, Gali BM. Acute perforated duodenal ulcer in Maiduguri: experience with simple closure and Helicobacter pylori eradication. West Afr J Med 2009;28:384-7. 4. Michelet I, Agresta F. Perforated peptic ulcer: laparoscopic approach. Eur J Surg 2000;166:405-8. 5. Tomtitchong P, Siribumrungwong B, Vilaichone RK, Kasetsuwan P, Matsukura N, Chaiyakunapruk N. Systematic review and meta-analysis: H. pylori eradication therapy after simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer. Helicobacter 2012;17:148-52. 6. Dakubo JC, Naaeder SB, Clegg-Lamptey JN. Gastroduodenal peptic ulcer perforation. East Afr Med J 2009;86:100-109. 7. Plummer JM, McFarlane ME, Newnham. Surgical management of perforated duodenal ulcer: the changing scene. West Indian Med J 2004;53:378-81.

8. Bin-Taleb AK, Razzaq RA, Al-Kathiri ZO. Management of perforated peptic ulcer in patients at a teaching hospital. Saudi Med J 2008;29:245-50. 9. Lobankov VM. Population heaviness of peptic ulcer disease: causing factors. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol 2010;11:78-83. 10. Andersen IB, Jrgensen T, Bonnevie O, Grnbaek M, Srensen TI. Smoking and alcohol intake as risk factors for bleeding and perforated peptic ulcers: a populationbased cohort study. Epidemiology 2000;11:434-9. 11. Kocer B, Surmeli S, Solak C, Unal B, Bozkurt B, Yildirim O,et al. Factors affecting mortality and morbidity in patients with peptic ulcer perforation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:565-70. 12. Dakubo JC, Naaeder SB, Clegg-Lamptey JN. Gastroduodenal peptic ulcer perforation. East Afr Med J 2009;86:100-9. 13. Nuhu A, Kassama Y. Experience with acute perforated duodenal ulcer in a West African population. Niger J Med 2008;17:403-6. 14. Tsugawa K, Koyanagi N, Hashizume M, Tomikawa M, Akahoshi K, Ayukawa K, et al. The therapeutic strategies in performing emergency surgery for gastroduodenal ulcer perforation in 130 patients over 70 years of age. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48:156-62. 15. Testini M, Portincasa P, Piccinni G, Lissidini G, Pellegrini F, Greco L. Significant factors associated with fatal outcome in emergency open surgery for perforated peptic ulcer.World J Gastroenterol 2003;9:2338-40. 16. El-Nakeeb A, Fikry A, Abd El-Hamed TM, Fouda el Y, El Awady S, Youssef T, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on ulcer recurrence after simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer. Int J Surg 2009;7:126-9. 17. Subedi SK, Afaq A, Adhikary S, Niraula SR, Agrawal CS. Factors influencing mortality in perforated duodenal ulcer following emergency surgical repair. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2007;46:31-5. 18. Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, Henderson C, Howden CW, Metz DC. Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion 2011;84:102-13. 19. Kim JM, Jeong SH, Lee YJ, Park ST, Choi SK, Hong SC,et al. Analysis of risk factors for postoperative morbidity in perforated peptic ulcer. J Gastric Cancer 2012;12:26-35. 20. Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Koy M, McHembe MD, Jaka HM, Kabangila R,et al. Clinical profile and outcome of surgical treatment of perforated peptic ulcers in Northwestern Tanzania: A tertiary hospital experience. World J Emerg Surg 2011;6:31. 21. Bashinskaya B, Nahed BV, Redjal N, Kahle KT, Walcott BP. Trends in Peptic Ulcer Disease and the Identification of Helicobacter Pylori as a Causative Organism: Population-based Estimates from the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J Glob Infect Dis 2011;3:366-70. 22. Coluccio G, Fornero G, Rosato L. [Our experience in the surgical treatment of perforated peptic ulcer]. Minerva Chir 1996;51:1035-8. 23. Rajesh V, Chandra SS, Smile SR. Risk factors predicting operative mortality in perforated peptic ulcer disease. Trop Gastroenterol 2003;24:148-50. Cite this article as: Parmar HD, Prajapati M, Shah R. Recent Trends in peptic perforation. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2013; 2:110-112. Source of Support: Nil Conflict of interest: None declared

112

International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health | 2013 | Vol 2 | Issue 1

You might also like

- Form by Name PTM Sma 19 (1Document440 pagesForm by Name PTM Sma 19 (1Chintya Permata SariNo ratings yet

- Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) :: A New Look at An Old DisorderDocument6 pagesImmune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) :: A New Look at An Old DisorderAsri Alifa SholehahNo ratings yet

- Cervix Uteri Cancer Staging: American Joint Committee On CancerDocument1 pageCervix Uteri Cancer Staging: American Joint Committee On CancerChintya Permata SariNo ratings yet

- Prostate SmallDocument1 pageProstate SmallChintya Permata SariNo ratings yet

- ClosedDocument2 pagesClosedChintya Permata SariNo ratings yet

- The Hip.Document5 pagesThe Hip.Chintya Permata SariNo ratings yet

- Nej Mic M 1200973Document1 pageNej Mic M 1200973Chintya Permata SariNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Fundamentals of Nursing 1Document2 pagesFundamentals of Nursing 1Alura Marez Doroteo100% (2)

- Manage healthcare facility designs in RevitDocument1 pageManage healthcare facility designs in RevitSoporte LexemaNo ratings yet

- Research On Prison HealthcDocument87 pagesResearch On Prison HealthcptsievccdNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Paper Nur 330Document13 pagesHealth Promotion Paper Nur 330api-625175559No ratings yet

- Management of Nursing Service & Education: Course DescriptionDocument12 pagesManagement of Nursing Service & Education: Course DescriptionrenjiniNo ratings yet

- Intubation Tray Contents Check ListDocument1 pageIntubation Tray Contents Check Listarjun_paul100% (3)

- Overview of pediatric nursing الباب الاولDocument2 pagesOverview of pediatric nursing الباب الاولmathio medhatNo ratings yet

- CHN - NCPDocument2 pagesCHN - NCPfhengNo ratings yet

- Haynes ResumeDocument1 pageHaynes Resumeapi-443388627No ratings yet

- Provider Directory Find Care UPMC Health Plan 2Document1 pageProvider Directory Find Care UPMC Health Plan 2Gonzalez Ruscalleda Marie NatashaNo ratings yet

- Small But Intriguing The Unfolding Story of Homeopathic Medicine PDFDocument7 pagesSmall But Intriguing The Unfolding Story of Homeopathic Medicine PDFweb3351No ratings yet

- Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) : Togo, AfricaDocument11 pagesSocial Determinants of Health (SDoH) : Togo, AfricaChantal SpendiffNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Amik SanglahDocument6 pagesJurnal Amik Sanglahslamet pujianto SkepNo ratings yet

- Worington Health CareDocument2 pagesWorington Health Carercbcsk cskNo ratings yet

- 1.Mcn FamilyDocument45 pages1.Mcn FamilymanilynNo ratings yet

- COVID Vaccination CertificateDocument1 pageCOVID Vaccination CertificateVeeraj SinghNo ratings yet

- Legal Aspects of Perioperative NursingDocument9 pagesLegal Aspects of Perioperative NursingZerrie lei Hart100% (2)

- AMA Retrospective AuditsDocument2 pagesAMA Retrospective AuditsEma ForgacsNo ratings yet

- Fall 2023 HNSC 4241 Syllabus R Alraei 1 2Document6 pagesFall 2023 HNSC 4241 Syllabus R Alraei 1 2api-711306298No ratings yet

- Contact Detail - CMCVelloreDocument155 pagesContact Detail - CMCVelloreAbhinita Sinha100% (1)

- Health Care Delivery SystemDocument42 pagesHealth Care Delivery SystemAnusha Verghese95% (20)

- NSW 190 Priority Skilled Occupation List - 2017-18Document4 pagesNSW 190 Priority Skilled Occupation List - 2017-18AzamNo ratings yet

- Angelie ADocument4 pagesAngelie AMaja TusonNo ratings yet

- About Rectal TubeDocument3 pagesAbout Rectal TubeElpanUmbalanNo ratings yet

- List of Life - MembersDocument100 pagesList of Life - Membersdrdineshsuman100% (1)

- Insurance Claim FormDocument4 pagesInsurance Claim FormIhjaz VarikkodanNo ratings yet

- NSC307 2021Document1 pageNSC307 2021NAZIRU HUDUNo ratings yet

- Patient at Risk Score (PARS) Clinical Guideline SummaryDocument5 pagesPatient at Risk Score (PARS) Clinical Guideline SummaryValtesondaSilvaNo ratings yet

- 16.11.24 FBonora - 15 Tips For SJT SuccessDocument65 pages16.11.24 FBonora - 15 Tips For SJT SuccessUmer AnwarNo ratings yet

- Global Regenerative Group Becomes Global Distributor For Pharmaceutical Wholesaler Prosupplier GMBH Representing Their CureOs® Synthetic BONE GRAFTDocument3 pagesGlobal Regenerative Group Becomes Global Distributor For Pharmaceutical Wholesaler Prosupplier GMBH Representing Their CureOs® Synthetic BONE GRAFTPR.comNo ratings yet