Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Civil Law Cases - Prelims

Uploaded by

lchieSOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

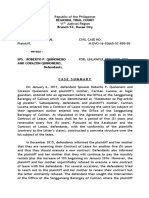

Civil Law Cases - Prelims

Uploaded by

lchieSCopyright:

Available Formats

21. Swagman vs. CA [GR NO.

161135, April 8, 2005] Facts: Sometime in 1996 and 1997, Swagman through Atty. Infante and Hegerty, its president and vice-president, respectively, obtained from Christian loans evidenced by three promissory notes dated 7 August 1996, 14 March 1997, and 14 July 1997. Each of thepromissory notes is in the amount of US$50,000 payable after three years from its date with an interest of 15% per annum payable every three months. In a letter dated 16 December 1998, Christian informed the petitioner corporation that he was terminating the loansand demanded from the latter payment of said loans. On 2 February 1999, Christian filed with the RTC a complaint for a sum of money and damages against the petitioner corporation, Hegerty, and Atty. Infante. The petitioner corporation, together with its president and vice-president, filed an Answer raising as defenses lack of cause of action. According to them, Christian had no cause of action because the three promissory notes were not yet due and demandable. The trial court ruled that under Section 5 of Rule 10 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, a complaint which states no cause of action may be cured by evidence presented without objection. Thus, even if the plaintiff had no cause of action at the time he filed the instant complaint, as defendants obligation are not yet due and demandable then, he may nevertheless recover on the first twopromissory notes in view of the introduction of evidence showing that the obligations covered by the two promissory notes are now due and demandable. When the instant case was filed on February 2, 1999, none of the promissory notes was due and demandable, but , the first and the second promissory notes have already matured during the course of the proceeding. Hence, payment is already due. This finding was affirmed in toto by the CA. Issue: Whether or not a complaint that lacks a cause of action at the time it was filed be cured by the accrual of a cause of action during the pendency of the case. Held: No. Cause of action, as defined in Section 2, Rule 2 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, is the act or omission by which a party violates the right of another. Its essential elements are as follows: 1. A right in favor of the plaintiff by whatever means and under whatever law it arises or is created; 2. An obligation on the part of the named defendant to respect or not to violate such right; and 3. Act or omission on the part of such defendant in violation of the right of the plaintiff or constituting a breach of the obligation of the defendant to the plaintiff for which the latter may maintain an action for recovery of damages or other appropriate relief.

It is, thus, only upon the occurrence of the last element that a cause of action arises, giving the plaintiff the right to maintain an action in court for recovery of damages or other appropriate relief. Such interpretation by the trial court and CA of Section 5, Rule 10 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure is erroneous. The curing effect under Section 5 is applicable only if a cause of action in fact exists at the time the complaint is filed, but the complaint is defective for failure to allege the essential facts. Amendments of pleadings are allowed under Rule 10 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure in order that the actual merits of a case may be determined in the most expeditious and inexpensive manner without regard to technicalities and that all other matters included in the case may be determined in a single proceeding, thereby avoiding multiplicity of suits.

22. Carolyn M. Garcia vs. Rica Marie S. Thio, GR No. 154878, 16 March 2007 FACTS Respondent Thio received from petitioner Garcia two crossed checks which amount to US$100,000 and US$500,000, respectively, payable to the order of Marilou Santiago. According to petitioner, respondent failed to pay the principal amounts of the loans when they fell due and so she filed a complaint for sum of money and damages with the RTC. Respondent denied that she contracted the two loans and countered that it was Marilou Satiago to whom petitioner lent the money. She claimed she was merely asked y petitioner to give the checks to Santiago. She issued the checks for P76,000 and P20,000 not as payment of interest but to accommodate petitioners request that respondent use her own checks instead of Santiagos. RTC ruled in favor of petitioner. CA reversed RTC and ruled that there was no contract of loan between the parties. ISSUE (1) Whether or not there was a contract of loan between petitioner and respondent. (2) Who borrowed money from petitioner, the respondent or Marilou Santiago? HELD (1) The Court held in the affirmative. A loan is a real contract, not consensual, and as such I perfected only upon the delivery of the object of the contract. Upon delivery of the contract of loan (in this case the money received by the debtor when the checks were encashed) the debtor

acquires ownership of such money or loan proceeds and is bound to pay the creditor an equal amount. It is undisputed that the checks were delivered to respondent. (2) However, the checks were crossed and payable not to the order of the respondent but to the order of a certain Marilou Santiago. Delivery is the act by which the res or substance is thereof placed within the actual or constructive possession or control of another. Although respondent did not physically receive the proceeds of the checks, these instruments were placed in her control and possession under an arrangement whereby she actually re-lent the amount to Santiago. Petition granted; judgment and resolution reversed and set aside. 23. Far East Bank & Trust v. Diaz Realty Inc., G.R. No. 138588, August 23, 2001 Facts: 1. Diaz and Co. obtained a loan from Pacific Banking Corp. in 1974 in the amount of P720,000 at 12% interest p.a. which was increased thereafter. The said loan was secured with a real estate mortgage over two parcels of land owned by Diaz Realty, herein respondent. Subsequently, the loan account was purchased by the petitioner Far East Bank (FEBTC). Two years after, the respondent through its President inquired about its obligation and upon learning of the outstanding obligation, it tendered payment in the form of an Interbank check in the amount of P1,450,000 in order to avoid the further imposition of interests. The payment was with a notation for the full settlement of the obligation. 2. The petitioner accepted the check but it alleged in its defense that it was merely a deposit. When the petitioner refused to release the mortgage, the respondent filed a suit. The lower court ruled that there was a valid tender of payment and ordered the petitioner to cancel the mortgage. Upon appeal, the appellate court affirmed the decision. Issue: Whether or not there was a valid tender of payment to extinguish the obligation of the respondent RULING: Yes. Although jurisprudence tells us that a check is not a legal tender and a creditor may validly refuse it, this dictum does not prevent a creditor from accepting a check as payment. Herein, the petitioner accepted the check and the same was cleared. A tender of payment is the definitive act of of offering the creditor what is due him or her, together with the demand that he accepts it. More important is that there must be a concurrence of intent, ability and capability to make good such offer, and must be absolute and must cover the amount due. The acts of the respondent manifest its intent, ability and capability. Hence, there was a valid tender of payment. Meanwhile, the transfer of credit from Pacific Bank to the petitioner did not involve an effective novation but an assignment of credit. As such, the petitioner has the right to collect the full value of the credit from the respondent subject to the conditions of the promissory note previously executed.

24. LICAROS v GATMAITAN FACTS: Abelardo Licaros invested his money worth$150,000 with Anglo-Asean Bank, a money market placement by way of deposit, based in the Republic of Venatu. Unexpectedly, he had a hard time getting back his investments as well as the interest earned. He then sought the counsel of Antonio Gatmaitan, a reputable banker and investor. They entered into an agreement,where a non-negotiable promissory note was to be executed in favor of Licaros worth $150,000, and that Gatmaitan would take over the value of the investment made by Licaros with the Anglo-Asean Bank at the former's expense. When Gatmaitan contacted the foreign bank, it said they will look into it, but it didn't prosper. Because of the inability to collect,Gatmaitan did not bother to pay Licaros the value of the promissory note. Licaros, however, believing that he had a right to collect from Gatmaitan regardless of the outcome, demanded payment, but was ignore. Licaros filed a complaint against Gatmaitan for the collection of the note. The trial court ruled in favor of Licaros, but CA reversed. ISSUE: Whether the memorandum of agreement between petitioner and respondent is one of assignment of credit or one of conventional subrogation RULING: It is a conventional subrogation. An assignment of credit has been defined as the process of transferring the right of the assignor to the assignee who would then have a right to proceed against the debtor. Consent of the debtor is not required is not necessary to product its legal effects, since notice of the assignment would be enough. On the other hand, subrogation of credit has been defined as the transfer of all the rights of the creditor to a third person, who substitutes him in all his rights. It requires that all the related parties thereto, the original creditor, the new creditor and the debtor, enter into a new agreement, requiring the consent of the debtor of such transfer of rights. In the case at hand, it was clearly stipulated by the parties in the memorandum of agreement that the express conformity of the third party (debtor) is needed. The memorandum contains a space for the signature of the Anglo-ASEAN Bank written therein "with our conforme". Without such signature, there was no transfer of rights. The usage of the word "Assignment" was used as a general term, since Gatmaitan was not a lawyer, and therefore was not well-versed with the language of the law.

25. Nereo J. PACULDO, petitioner, vs. Bonifacio C. REGALADO, respondent [2000] On Dec. 27, 1990: Contract of Lease between Paculdo (lessee) & Regalado (lessor) over a parcel of land w/a wet market bldg located along Don Mariano Marcos Ave., Fairview Park, QC. Contract was for 5 yrs from this date w/monthly rental of P450k payable w/in first 5 days of each month at Regalados office + 2% penalty for every month of late payment. Paculdo leased 11 other properties from Regalado, 10 of w/c were located in Fairview while the 11th was located along Quirino Highway, QC. Paculdo also purchased 8 units of heavy equipment & vehicles from Regalado amounting to P1,020,000.00. Then, on July 15, 1991, Regalado informed Paculdo that his payment was to be applied to the following: monthly rentals for the wet market, Quirino lot, and the heavy equipment purchased. This letter had no conformity portion. Paculdo did not act on the letter. On Nov. 19, 1991, Regalado proposed that Paculdos security deposit for the Quirino lot be applied as partial payment for his account under the subject lot as well as to the real estate taxes on the Quirino lot. Paculdo did not object and he signed the conformity portion. Regalado claims that Paculdo failed to pay P361, 895.55 in rental for the month of May, 1992 and monthly rental of P450k for the months of June & July, 1992. Thus he sent 2 demand letters (both in July, 1992) asking for payment and later on asked Paculdo to vacate the property. Regalado mortgaged the land under the contract to Monte de Piedad Savings Bank. It included the improvements introduced by Paculdo amounting to P35M. Mortgage was used as security for a loan amounting to P20M. On Aug. 12, 1992 onwards, Regalado refused to accept Paculdos daily rental payments. Ultimately, on Aug. 20, 1992, Paculdo filed an action for injunction & damages to enjoin Regalado from disturbing his possession of property under the contract. Regalado on the other hand, filed a complaint for ejectment against Paculdo. Later on withdrawn and then re-filed w/claim of P3,924,000.00. MTC: Ordered Paculdo to vacate the premises & pay P527,119.27 of unpaid monthly rentals as of June 30, 1992 w/2% interest + P450k/month w/2% interest from July 1992 onwards until place has been vacated & turned over to Regalado + P5M for attys fees + costs. Feb. 19, 1994: Regalado w/50 armed security guards forcibly entered the property & took possession of the wet market. RTC affirmed MTC decision. Issued a writ of execution thus Paculdo vacated the property voluntarily & there was complete turn over by July 12, 1994.

Paculdo appealed to the CA claiming that: He paid P11,478,121.85 as security deposit & rentals on the wet market building. Portions of the amount paid was applied by Regalado w/o his consent, to his other obligations. Vouchers & receipts indicated that the payments were made for rentals, proof of Paculdos declaration as to w/c obligation the payment must be applied. CA: Dismissed the petition for lack of merit. Paculdo impliedly consented to Regalados application of payment to his other obligations. Issue: WON Paculdo was truly in arrears in the payment of rentals on the subject property at the time of the filing of the complaint for ejectment. NO. Ratio: 1. Based on MTC & RTC findings, Paculdo paid a total of P10,949,447.18 to Regalado as of July 2, 1992. And if this will be applied solely to the rentals on the Fairview wet market, there would even be an excess payment of P1,049,447.18. (see p.139 for computation) 2. Paculdo goes back to the July 15, 1991 letter. He emphasized that applying the payment to the purchased equipment was crucial because it was equivalent to 2 mos rental & was the basis for the ejectment case. He further claims that his silence/lack of protest did not mean consent; rather, it was a rejection. 3. CC Art. 1252 & 1254: Debtor has the rt to specify w/c among his various obligations to the same creditor is to be satisfied at the time of making the payment. If the debtor did not exercise this rt, law provides that no payment is to be made to a debt that is not yet due (CC Art. 1252) and payment has to be applied first to the debt most onerous to the debtor (CC Art. 1254). a. Paculdo made it clear that payments were to be applied to his rental obligations on the wet market property. b. Regalado claims that Paculdo assented to the application as inferred from his silence. c. A big chunk of the amount paid went into the satisfaction of an obligation w/c was not yet due & demandable (payment of heavy equipment). Application was contrary to law. d. Paculdos silence was not tantamount to consent. Consent must be clear & definite. There was no meeting of the minds. Though there was an offer by Regalado, there was no acceptance by Paculdo. Even if Paculdo did not exercise his rt to choose the obligation to be satisfied first & such rt was transferred to Regalado, latters choice is still subject to formers consent. e. Lease over the Fairview property is the most onerous among all the obligations of petitioner to respondent. Its a going-concern (?) and investments on the improvements were made amounting to P35M. Paculdo was bound to lose more if lease would be rescinded than if the contract of sale of heavy equipment would not proceed. Holding: Petition granted. CA decision reversed & set aside.

You might also like

- WELCOMING REMARKS Wedding ScriptDocument7 pagesWELCOMING REMARKS Wedding Scriptmaranatha rallosNo ratings yet

- Bank Certification of Specimen SignatureDocument1 pageBank Certification of Specimen SignatureIlaw-Santonia Law OfficeNo ratings yet

- Contract As Defined by Article 1305 of The Civil CodeDocument1 pageContract As Defined by Article 1305 of The Civil CodelchieSNo ratings yet

- Child Welfare Code PDFDocument30 pagesChild Welfare Code PDFlchieSNo ratings yet

- Chain of CustodyDocument8 pagesChain of CustodyKuya Kim100% (1)

- General Contract CorporationsDocument2 pagesGeneral Contract CorporationsJa Mi LahNo ratings yet

- Effectivity of OrdinanceDocument7 pagesEffectivity of OrdinanceSoc Sabile100% (2)

- Landbank - Letter of AuthorizationDocument1 pageLandbank - Letter of AuthorizationlchieS80% (5)

- Sample Format of Judicial Affidavit (English)Document6 pagesSample Format of Judicial Affidavit (English)Samantha BugayNo ratings yet

- Toyota SwiftDocument1 pageToyota SwiftlchieSNo ratings yet

- Calendar - PrintableDocument9 pagesCalendar - PrintablelchieSNo ratings yet

- Mou 1Document3 pagesMou 1karenNo ratings yet

- Children Welfare Code of Davao City ApprovedDocument27 pagesChildren Welfare Code of Davao City ApprovedlchieSNo ratings yet

- Case Summary (Unlawful Detainer)Document3 pagesCase Summary (Unlawful Detainer)lchieSNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence - Unlawful DetainerDocument18 pagesJurisprudence - Unlawful DetainerlchieSNo ratings yet

- Chain of CustodyDocument8 pagesChain of CustodyKuya Kim100% (1)

- Cases On BP BLG 22Document23 pagesCases On BP BLG 22lchieSNo ratings yet

- Chain of CustodyDocument8 pagesChain of CustodyKuya Kim100% (1)

- Cases On BP BLG 22Document23 pagesCases On BP BLG 22lchieSNo ratings yet

- MCLE SkedDocument1 pageMCLE SkedlchieSNo ratings yet

- Notes On Inhibition of JudgesDocument3 pagesNotes On Inhibition of JudgeslchieSNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence On BP 22Document2 pagesJurisprudence On BP 22lchieSNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence - Unlawful DetainerDocument18 pagesJurisprudence - Unlawful DetainerlchieSNo ratings yet

- Notes On Unlawful DetainerDocument2 pagesNotes On Unlawful DetainerlchieSNo ratings yet

- Law and Logic (Fallacies)Document10 pagesLaw and Logic (Fallacies)Arbie Dela TorreNo ratings yet

- Election Law Reviewer 10.12.16 Clean PDFDocument110 pagesElection Law Reviewer 10.12.16 Clean PDFlchieSNo ratings yet

- Unilateral Deed of Sale - SAMPLEDocument2 pagesUnilateral Deed of Sale - SAMPLElchieS86% (37)

- 2015 SALN FormDocument4 pages2015 SALN Formwyclef_chin100% (6)

- Law and Logic (Fallacies)Document10 pagesLaw and Logic (Fallacies)Arbie Dela TorreNo ratings yet

- Election Law Reviewer 10.12.16 Clean PDFDocument110 pagesElection Law Reviewer 10.12.16 Clean PDFlchieSNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Case StudyDocument2 pagesCase StudyJazmine Anne ManilaNo ratings yet

- Extinguishment of Obligation. Case STUDY.Document10 pagesExtinguishment of Obligation. Case STUDY.Rikmer LacandulaNo ratings yet

- Central Bank V CA ObliconDocument2 pagesCentral Bank V CA ObliconSannemarijeNo ratings yet

- Mortgage Fraud Secrets ExposedDocument8 pagesMortgage Fraud Secrets Exposedrighttocancel93% (14)

- Revised - Negotiable Instruments Law - Annotated.mpp.Document473 pagesRevised - Negotiable Instruments Law - Annotated.mpp.EstelaBenegildo100% (3)

- International Exchnage Bank vs. Sps. BrionesDocument2 pagesInternational Exchnage Bank vs. Sps. Brionesk santosNo ratings yet

- Credit TransactionsDocument7 pagesCredit TransactionstinctNo ratings yet

- Course 8 Private Banking 47Document47 pagesCourse 8 Private Banking 47halcino100% (5)

- Zephyr GlossaryDocument22 pagesZephyr GlossaryMikael TovmasianNo ratings yet

- Bills of Exchange and Promissory Notes - UAE Legal Position PDFDocument2 pagesBills of Exchange and Promissory Notes - UAE Legal Position PDFrbmjainNo ratings yet

- C P A R CPA Review School of The PhilippinesDocument21 pagesC P A R CPA Review School of The PhilippinesMae Gamit LaglivaNo ratings yet

- BPI Vs Sps YuDocument8 pagesBPI Vs Sps YuNicoleAngeliqueNo ratings yet

- Agro vs. CADocument1 pageAgro vs. CAJanlo FevidalNo ratings yet

- Real Estate OutlineDocument13 pagesReal Estate Outlinerrccu100% (2)

- Compiled CasesDocument413 pagesCompiled CasesPao RINo ratings yet

- New Sampaguita vs. PNBDocument36 pagesNew Sampaguita vs. PNBAnonymous WDEHEGxDhNo ratings yet

- 16 Lipat v. Pacific Banking Corp.20160314-1331-Ol3x6tDocument10 pages16 Lipat v. Pacific Banking Corp.20160314-1331-Ol3x6tMark De JesusNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument14 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Security Bank and Trust Co vs. RTC MakatiDocument3 pagesSecurity Bank and Trust Co vs. RTC Makaticmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Licaros vs. GatmaitanDocument1 pageLicaros vs. GatmaitanRosh LepzNo ratings yet

- Chart of AccountsDocument6 pagesChart of AccountsJenniferNo ratings yet

- Case Matrix For Credit TransacitonsDocument19 pagesCase Matrix For Credit TransacitonsJudith AlisuagNo ratings yet

- UP 1990 To 2014 NIL Bar Questions With Suggested AnswersDocument22 pagesUP 1990 To 2014 NIL Bar Questions With Suggested AnswersCindy DondoyanoNo ratings yet

- Farhat ProjectDocument49 pagesFarhat ProjectAbdur Rafe Al-AwlakiNo ratings yet

- Credit AgreementDocument102 pagesCredit AgreementKnowledge Guru100% (1)

- Nego Bar Exam Up To 2010Document21 pagesNego Bar Exam Up To 2010carl fuerzasNo ratings yet

- Credit ManagementDocument86 pagesCredit ManagementJeyaprabha VMNo ratings yet

- DPC-1 Part-1Document17 pagesDPC-1 Part-1kiranNo ratings yet

- Republic Planters Bank-Vs-CaDocument2 pagesRepublic Planters Bank-Vs-CaMadeleine DinoNo ratings yet