Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rate of Return

Uploaded by

Audrey Patrick KallaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rate of Return

Uploaded by

Audrey Patrick KallaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Rate of Return on Investment By William R.

Gillam, FCAS VP/Actuary National Council on Compensation Insurance

ABSTRACT

There is much discussion today on the topic of rate of return, without a clear definition of its parameters. This monograph carefully defines the return and the investment, numerator and denominator of the rate. The author debunks certain common misuses of accounting terms. There can be no investment income on a loss reserve. Return on capital is not the same thing as return on surplus, which is close to meaningless. An example relating the return on investment to the profit provision in the rates is provided.

The Rate of Return on Investment in the Business of Insurance By William R. Gillam, FCAS VP/Actuary National Council on Compensation Insurance

Introduction There is much discussion today on the topic of rate of return, without a clear definition of its parameters. This monograph carefully defines the return and the investment, the numerator and denominator of the rate of return.

It is hoped that the presentation elicits a higher understanding of the elements and considerations necessary to measure the return on investment in the insurance business. The point of view of the investor should be differentiated from those of the policyholder or the statutory surplus (if that has a point of view).

The source of the following material is the NCCI Internal Rate of Return model, which relates the profit loading in rates to the return on capital invested in the insurance company.

For ease of presentation, this article is written as though the authors opinions are unequivocal truths, and the reader should remain careful and critical. The writers perspective is his own, not that of his employer, the reader, or any of the various parties to the insurance transaction.

Outline This paper provides a high level perspective on the following questions:

1)

What is the capital invested in an insurance enterprise?

Exactly how much capital does the investor have committed? This invested capital is the denominator in the rate of return. From this point of view, the cost of capital can be thought of as the rate of return an investor expects, or targets, when he provides capital to an enterprise of a specific level of risk.

The investment in an insurance company must not be confused with policyholders' surplus. The latter is a balancing item, i.e., assets minus liabilities, and the value of each of these is quite volatile. The capital invested in a stock company may change over time, but in a way only loosely related to the size of the policyholders' surplus.

2)

What is the return on capital invested in the insurance business?

For purposes of this monograph, the appropriate measure of the numerator is total return, including investment income and capital gains, as well as underwriting return. This is consistent with the point of view of the investor, whose expected total return is the cost of capital.

For simplicity, tax is not considered, nor is there any in-depth consideration of realized or unrealized capital gains.

This monograph does not discuss what the actual cost of capital is or should be in the insurance industry. In other words, we want to propose how it should be measured and related to the provision for profit in the rates, not how much it should be.

3)

What is the correct provision in rates to achieve the targeted return on invested capital?

This is the ratemaker's non-trivial chore. The foremost impediment is that rates must generally be made before insurance is provided, generally using estimates of loss and expense and cash

flow models of the insurance transaction. The loss process is stochastic, but models will have to be deterministic.

A sample calculation using the internal rate of return model is provided below.

The future is uncertain, and even models which use statistical distributions recognizing process variance will be fraught with parameter risk. Some provision for this should be in the rate, and this should probably be related to the relative difficulty of pricing specific coverage. This paper does not discuss derivation of such a provision.

Invested Capital

The capital invested in an insurance company is not the same as the surplus. It is better to think of surplus as a budgetary requirement of the business of insurance. It should become clearer in the example below that the necessary, or "par", surplus determines required capital investment. To the extent underwriting (including investment income on the cash flow of the process) does not provide adequate surplus, invested capital must fill the gap. It is no accident it is called the policyholder's surplus rather than "the investors'" or "owners'" surplus.

Surplus is necessary to support liabilities which are uncertain, particularly Unearned Premium and Loss Reserves (UPR and LR). Note that surplus supporting UPR is a slight variation on the traditional premium to surplus rule of thumb which says the ratio of written premium to par surplus ought not be significantly more than two. Unearned premium represents highly uncertain liability for losses that have not yet occurred. It tends to be of the same magnitude as written premiums, and the ratio of UPR to surplus should be about the same.

Loss reserves are a major estimated liability item which require a par surplus, but perhaps with a lower requirement than UPR since reserves are evaluated after the associated premium has been earned and, usually, most losses have been reported. Perhaps the ratio of loss reserves to surplus ought to be no more than five.

For purposes of this exposition, the author has selected a UPR to surplus ratio of two and a LR to surplus ratio of four. This par surplus could undoubtedly be more accurately estimated, perhaps using Risk Based Capital techniques. Such an estimate would be independent of the overcapitalization or under-capitalization of specific insurers. Alternatively, the values could be

estimated empirically, perhaps using a regression on the sample ratios of the many companies writing the subject line of business. Both approaches are outside the scope of this paper.

Return on Investment

Interest rates and inflation are moderate and stable today, but will probably never go back to the low (and stable) rates of the first half of this century. Return to the insurance business has become as much a function of cash flow and the time value of money as the underwriting results. In recent years, investment income has made the difference between the failure and success of many major insurance companies. inconsequential; that time is past. There may have been a time when it was nice but

At the risk of hammering a point, this monograph considers both the insurance transaction and its potential for investment income from the point of view of the investor.

In order to measure investment income generated by the insurance transaction, it is necessary to analyze the cash flows of the transaction. It is very difficult to do such an analysis starting with statutory accounting, especially if there is any confusion between investible assets and liabilities.

There can be no investment income on loss reserves; as Charlie Hachemeister was fond of relating, investment income accrues to assets, not liabilities.

Given cash flow patterns for premium and loss, the higher the combined ratio, the greater the loss reserve but the lower the potential for investment income on funds provided by premium income alone. Writing to a high combined ratio reduces assets while generally increasing liabilities. Without additional investment, income and surplus will both be reduced. This could change return as a function of surplus in ways that are not intuitive. With a high combined ratio, more capital must be invested to return surplus to par, and the rate of return to the investor would decrease. This, in part, is why measuring return on surplus leads to distortions.

Ratemaking

The profit loading in rates does not bear a simple algebraic relationship to the expected underwriting profit, return on investment, or premium to surplus ratios. The loading must consider not only these three things, but also the estimated cash flows of premium, loss and expense, the uncertainty of those estimations, and (I've added) the par reserve to surplus ratios. Investment Income can accrue to the necessary invested capital as well as the cash flow from underwriting. In effect, we can back solve for the invested capital by an accounting analysis of what is necessary to satisfy surplus requirements.

Generally, cash flow models are necessary to relate the profit provision in the rates to the return on investment. The cash flow from underwriting is a stochastic process. Rates must be made before the cash flows are known. Modeling these lends a great potential for parameter risk. Consideration must be made for the relative difficulty of estimating adequate rates. The greater the difficulty, the greater the risk.

The following is a simple model of a hypothetical insurance transaction from the point of view of the investor, and calculates the internal rate of return. Other cash flow models are possible. (Dollar figures are rounded to whole dollar.)

The initial calculation using a 5% underwriting profit provision results in an 18.2% return on investment. Suppose this rate is unacceptably high, as it might be to a regulator, a politician or even a carrier bent on competition. Thus, as a second experiment, we try using the lower profit provision of 0%. This results in a +11.6% return.

We also calculate the rates of return on surplus as +31.1% and +20.5% for the respective scenarios. The reader should ask the question: exactly whose return is this?

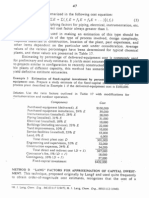

Internal Rate of Return Model

1.

Initial Calculation. Start up company will write $1,000 in premium 1/1/98. Expenses are $250, paid immediately. Losses are $700, paid at year-end. The profit loading in the rates is $50 or 5% of the premium. For simplicity, assume no taxes. Par surplus to UPR is 0.50. Par surplus to LR is 0.25. Balance @ 1/1/98, after expenses have been paid. Liabilities UPR LR $1,000 0 $1,000

Assets Cash from premium transaction Necessary Capital Investment* $ 750 750 $1,500 $ 500

Par Surplus

*Necessary to support surplus of $500, half of the UPR. Evaluating @ 7/1/98, let's assume the $700 loss has occurred, but has not been paid. Half the premium has been earned. Interest income has been 3% of $1,500 for six months, or $45. Liabilities UPR LR

$ 500 700 $1,200

Assets (1500)(1.03) Necessary additional capital investment $1,545 80 $ 1,625

Par Surplus (0.5)(500) + (0.25)(700)

$ 425

@ 12/31/98, the end of the year, all premium is earned, $700 losses are paid and investment income of $49 accrues to the assets supporting the transaction.

Liabilities UPR LR

$ $

0 0 0

Assets (1,625)(1.03)-(700) Surplus $ 974 $ 974

The ending surplus is returned to the investor. The Internal Rate of Return is the rate, which discounts the invested cash flows to . The cash flows are the initial $750, the addition of $80 at six months and the return of $974 surplus at year-end. Using v = () 750 + 80v.5 - 974v = 0 Solving v.5 = .920 v = .846 i = 18.2%

the internal rate of return to the investor. We can easily calculate the total return as a percent of average surplus. U/W Profit Investment Income ($45+$49) Total Income Surplus (500 + 425) 2 Rate of return $ 50 $ 94 $ 144 $ 463 31.1%

2.

After reducing the profit loading in the rates, write $950 in premium. @ 1/1/98 Liabilities UPR LR

$ 950 0 $ 950

Assets Cash from premium transaction Necessary Capital Investment* $ 700 725 $1,425 $ 475

Par Surplus

*Necessary to support surplus of $475, half of the UPR. @ 7/1/98 Assume $43 of investment income Liabilities UPR LR

$ 475 700 $1,175 $1,468 120 $1,588

Assets (add 43) Additional Capital

Par Surplus (.5)(475)+(.25)(700) @ 12/31/98 add $48 investment income, and pay the losses. Assets $48 + $1,588- $700 Liabilities Liquidating this, the internal rate of return is i = 11.6%

$ 413

$ 936 0

The total return is $91 on average surplus of $444, or a rate of +20.5%

You might also like

- What is meant by StereoisomersDocument37 pagesWhat is meant by StereoisomersAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- AbsorptionStripping PDFDocument25 pagesAbsorptionStripping PDFJuan Camilo HenaoNo ratings yet

- SAFETY AND SECURITY PLANDocument11 pagesSAFETY AND SECURITY PLANAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Absorption ColumnsDocument55 pagesAbsorption ColumnsAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Ads or PtionDocument141 pagesAds or PtionAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Metallurgical Extractions - SL - LLDocument37 pagesMetallurgical Extractions - SL - LLRoger RumbuNo ratings yet

- Ammonia StorageDocument6 pagesAmmonia Storagemsathishkm3911No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Process DiagramsDocument36 pagesChapter 1 - Process Diagramsmrajim93No ratings yet

- Fishbone Diagrams for Needs AssessmentDocument4 pagesFishbone Diagrams for Needs Assessment680105No ratings yet

- Unit Operations and Processes in Environmental EngineeringDocument815 pagesUnit Operations and Processes in Environmental EngineeringAudrey Patrick Kalla89% (28)

- Opeating CostDocument0 pagesOpeating CostAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Transport PhenomenaDocument82 pagesTransport PhenomenaAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- CHE 425 Engineering Economics and Design Principles NotesDocument93 pagesCHE 425 Engineering Economics and Design Principles NotesAudrey Patrick Kalla50% (2)

- Ads or PtionDocument141 pagesAds or PtionAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Opeating CostDocument0 pagesOpeating CostAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Cap CostDocument10 pagesCap CostAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - QDocument32 pagesChapter 10 - Qmohammedakbar88No ratings yet

- Eng Econ SlidesDocument34 pagesEng Econ Slidesاحمد عمر حديدNo ratings yet

- Paint Production Process DiagramDocument4 pagesPaint Production Process DiagramQasim SarwarNo ratings yet

- .Cost EstimationDocument15 pages.Cost EstimationAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Estimating The Fixed (FCI) and Total Capital Investments (TCI)Document3 pagesEstimating The Fixed (FCI) and Total Capital Investments (TCI)Tony StarkNo ratings yet

- EiaDocument16 pagesEiaAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Design of Heat ExchangersDocument20 pagesDesign of Heat ExchangersSudhir JadhavNo ratings yet

- C Section 2 Facility Description - cpd2014Document6 pagesC Section 2 Facility Description - cpd2014Audrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- B.tech Project - cpd2014Document85 pagesB.tech Project - cpd2014Audrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Heat Exchanger Types and CalculationsDocument16 pagesHeat Exchanger Types and CalculationsAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- E2 PracticeSolution - Magnetic FieldDocument5 pagesE2 PracticeSolution - Magnetic FieldAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Ch27.magnetic FieldDocument29 pagesCh27.magnetic FieldAudrey Patrick KallaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- AI HandbookDocument108 pagesAI HandbookwertyderryNo ratings yet

- Excel Professional Services, Inc.: Discussion QuestionsDocument6 pagesExcel Professional Services, Inc.: Discussion QuestionskæsiiiNo ratings yet

- Flood Control Thesis PhilippinesDocument6 pagesFlood Control Thesis PhilippinesCrystal Sanchez100% (2)

- Midterm Exam Questions on Disaster Readiness and Risk ReductionDocument6 pagesMidterm Exam Questions on Disaster Readiness and Risk ReductionMarjorie Brondo100% (1)

- Project 4.4.2: Heart Disease Interventions - Principles of BiomedicalDocument6 pagesProject 4.4.2: Heart Disease Interventions - Principles of BiomedicalMATTHEW DIAZNo ratings yet

- Hooper Et Al 2013 - Org FosforadosDocument17 pagesHooper Et Al 2013 - Org FosforadosDanny GarciaNo ratings yet

- Vol-1 - Issue-8 Full Volume PDFDocument151 pagesVol-1 - Issue-8 Full Volume PDFgita76321No ratings yet

- A Project Report On Portfolio ManagementDocument30 pagesA Project Report On Portfolio ManagementmonasreeNo ratings yet

- Health and Safety Management Manual With Procedures ExampleDocument13 pagesHealth and Safety Management Manual With Procedures ExampleVepxvia NadiradzeNo ratings yet

- EIA Study 110 KV OHTL Skopje1 - Jugohrom - Tetovo 1 - FinalDocument247 pagesEIA Study 110 KV OHTL Skopje1 - Jugohrom - Tetovo 1 - FinalLidija StojanovaNo ratings yet

- Body Art Consent and Health Disclosure Form For Tattooing and PiercingDocument1 pageBody Art Consent and Health Disclosure Form For Tattooing and PiercingDanielNo ratings yet

- 42R-08 Risk Analysis and Contingency Determination Using Parametric EstimatingDocument9 pages42R-08 Risk Analysis and Contingency Determination Using Parametric EstimatingDody BdgNo ratings yet

- Monthly Report Template Project ReportDocument23 pagesMonthly Report Template Project ReportfadliNo ratings yet

- All Answers in ModuleDocument8 pagesAll Answers in ModulePatricia TorrecampoNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Prostate CancerDocument11 pagesRisk Factors For Prostate CancerTaeshon TagNo ratings yet

- Business Continuity Foundation Sample Exam TitleDocument14 pagesBusiness Continuity Foundation Sample Exam Titlemahesh2013No ratings yet

- Corporate Social Performance and Cost of Debt The Relationship PDFDocument19 pagesCorporate Social Performance and Cost of Debt The Relationship PDFusiNo ratings yet

- Work at Heights PermitDocument4 pagesWork at Heights Permitrashid zamanNo ratings yet

- IJM Competencies - Descriptions & ExpectationDocument7 pagesIJM Competencies - Descriptions & ExpectationSaiful Idham Bin Mohd HusainNo ratings yet

- Unilever Business Report - BSFDocument14 pagesUnilever Business Report - BSFsong neeNo ratings yet

- Safe Work Method StatementDocument11 pagesSafe Work Method StatementJNo ratings yet

- Decision MakingDocument20 pagesDecision MakingAnton FernandoNo ratings yet

- Internship Report On Credit Risk Management of Bank Asia LimitedDocument51 pagesInternship Report On Credit Risk Management of Bank Asia LimitedNavid Imtiaj80% (5)

- 04 ISPEs Guides and How They Apply To Cleaning and Cleaning Validation by Stephanie WilkinsDocument33 pages04 ISPEs Guides and How They Apply To Cleaning and Cleaning Validation by Stephanie Wilkinsmjamil0995100% (1)

- Global Payplus BrochureDocument16 pagesGlobal Payplus BrochureGirishNo ratings yet

- Elshafie Elzubier Elsiddig Ali: EducationDocument4 pagesElshafie Elzubier Elsiddig Ali: EducationShafie ZubierNo ratings yet

- JSA .Hendra Pouring Congcrete by Mixer TruckDocument2 pagesJSA .Hendra Pouring Congcrete by Mixer TruckMuhamad Rizki AzisNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and Mandatory Vaccination: Ethical Considerations and CaveatsDocument5 pagesCOVID-19 and Mandatory Vaccination: Ethical Considerations and CaveatsAngelo Christian B. OreñadaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document51 pagesChapter 1chaterine larasatiNo ratings yet

- CPA Part (1) Detailed Syllabus For All SubjectsDocument21 pagesCPA Part (1) Detailed Syllabus For All SubjectsLin AungNo ratings yet