Professional Documents

Culture Documents

North American P-51 Mustang

Uploaded by

magyaralbaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

North American P-51 Mustang

Uploaded by

magyaralbaCopyright:

Available Formats

North American

1

Mustang

North American

us an

Ken Delve

Kev Darling

Kev Darling

Martin W. Bowman

te ePa

Jerry utt

Barry Jone

K v arling

Martin W. B wman

P t r . mith

K v Darling

Barry Jone

ott Thompson

Martin W. Bowman

Ron Ma kay

Martin W. Bowman

Jerry cutts

teve Pace

David Baker

Ray anger

Peter . mith

Kev Darling

Malcolm Hill

Barry Jones

Other titles in th rowood Aviation erie

Avro Lancaster

Avro Vulcan

Blackburn Buccaneer

Boeing 747

Boeing B-29 uperforrre s

Bristol Beaufighter

Briti h Experimental Turbojet Aircraft

Concorde

Con olidated B-24 Liberator

Curtiss B2 Helldiver

De Havilland omet

De Havilland Twin-Boom Fighters

Douglas Havoc and Bo ton

English Electric Lightning

Heinkel HIll

Lockheed F-104 tarfight r

Lockheed P-38 Lightning

Lockheed R-71 Bla kbird

Messerschmitt Me 262

Nieuport Aircraft of World War One

Petlyakov Pe-2 Peshka

upermarine eafire

Vicker Vi count and Vanguard

V-Bomber

Malcolm V. Lowe

~ C I

The Crowood Press

Mustang Specifications

Mustang Production

RAF Mustangs

Mustangs in Europe

Air National Guard Mustangs

Firsr published in 2009 by

The Crowood Press Lrd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wilrshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

Malcolm V. Lowe 2009

All righrs reserved. No parr of rhis publicarion

may be reproduced or rransmirred in any form or

by any means, elecrronic or mechanical, including

phorocopy, recording, or any informarion srorage

and retrieval sysrem, wirhour permission in wriring

from rhe publishers.

Brirish Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Dara

A caralogue record for rhis book is available from

rhe Brirish Library.

ISBN 978 1 861268303

Typeser by Servis Filmserring Lrd, Srockporr, Cheshire

Prinred and bound in India by Replika Press

Contents

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Foreword

1 CREATING A LEGEND

2 FROM PROTOTYPE TO LOW-LEVEL SUCCESS

3 THE FIRST AMERICAN MUSTANGS

4 DEVELOPMENT OF A THOROUGHBRED

5 LONG-RANGE ESCORT

6 FAR EAST BATTLEGROUND

7 POST-WAR SERVICE AND LIGHTWEIGHTS

8 TWINS, CAVALIERS AND ENFORCERS

9 RETURN TO THE FRONT LINE

10 BUILDING THE MUSTANG

11 EXPORT AND FOREIGN-OPERATED MUSTANGS

12 AIR RACERS, WARBIRDS AND NEW PRODUCTION

Appendix I

Appendix II

Appendix III

Appendix IV

Appendix V

Abbreviations

Further Reading

Selected Websites

Index

5

6

9

11

30

52

69

85

133

149

166

185

198

215

243

254

256

259

261

263

265

267

268

269

Introduction and AcknowledgeDlents

Introduction

Few warplanes can have had uch a sig-

nificant impact in warfare, or gained uch

enduring popularity, as North American

Aviation' beautiful P-51 Mustang.

Created as a private-venture project by

a company that was not officially rec-

ognized in its own country as worthy of

designing fightcr aircraft, the Mu tang

grew out of Britain' overwhelming need

for large quantities of modern high-per-

formance fighters in the early stages of the

Second World War. It was not, as incor-

rectly claimed by many published source,

the product of a Briti h requirement or

specification. Rather, it was one of the

very few succes ful warplane in hi tory

that was conceived without an official

specification ever being raised before its

creation. Indeed, it was born as the result

of amicable and unofficial negotiations

between North American's company offi-

cials and Briti h government representa-

tives in the U A. The end result was one

of history's great aircraft, which became a

vital element of the growing and eventu-

ally overwhelming Allied aerial domina-

tion as the Second World War drew to its

ultimately successful conclusion.

The first Mu tang was completed in a

very short time, less than 120 day, and

it proved to have a performance better

than most, if not all, of its European

counterparts of the time, flying faster and

carrying more fuel. It has passed into the

popular mythology of World War Two

that Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring,

the chief of Nazi Germany's Luftwaffe,

claimed that when he saw Mustangs oper-

ating freely over Berlin he knew that the

war was lost for Germany. Yet there are

a number of myths and half-truths about

the Mustang that have grown to become

establ ished 'facts'. Perhaps one of the

most obvious is the virtual writing-off

by many historians of the early, Allison-

engined Mustangs. Certainly it is true

that the Mustang changed from being

a workhorse into a thoroughbred when

the superlative, British-designed Rolls-

Royce Merlin engine was mated during

1942 to the basic Mustang airframe. In its

initial production versions the Mu tang

was powered by the successful if unspec-

tacular Allison V-I 710 piston engine,

intended for low- to medium-level oper-

ations. With this engine installed the

Mustang began life as a workhorse at low

to medium levels, and at altitudes bel w

15,000ft (4,600m) it became a depend-

able if unspectacular (and perhaps more

importantly, unsung) warplane that wa

nevertheless much appreciated by many

of its pilots and ground crew. Alii on-

ngined Mu tangs went into operational

service with Britain's Royal Air Force

(RAF) in 1942, a full year before the

USAAF ever used the type in combat.

The RAF succe fully flew the Allison

Mustang operationally, albeit in dwin-

dling numbers, right up to the end of the

war in Europe in May 1945. The Allison

Mustang was an excellent warplane in

its own right, and deserves much more

fanfare than it has ever received.

There are also myths about how long

it took orth American to design and

build the first Mustang, whose idea it

was originally to mate the Merlin engine

with the Mu tang airframe, and so on.

Perhaps one of the great injustice done

to the Mustang over the year is the

spreading of the extraordinary myth that

the Mustang's design was based on that

of the antiquated Curtiss P-40, or even,

quite unbelievably, that the Mustang was

a derivative of Germany' Messerschmitt

Bf 109. Many of the e points are explored

in the coming pages, but one statement

that cannot be disputed concerning the

Mustang is the kill, determination and

courage of tho e who took thi superb

aircraft into battle, and the quiet behind-

the-scenes profe ionali m of those who

worked on the aircraft and prepared them

for combat, often in the most appalling

conditions 'in the field'. This applied to

both the Allison- and Merlin-powered

Mustang, but without doubt the mating

6

of the excellent Merlin with the basic

Mustang airfram created a warplane of

extraordinary capability and perform-

ance that literally b ame a ignificant,

ome would say vital, tool in the Allied

ar enal a World War Two wor on. Yet

it i int re ting to note that originally the

Mustang's own 'local' arm d for es in the

U A had little or no intere t in the type.

This delayed the Mu tang's introduction

into service with AAF front-line units

by at least a year, if n t longer. Once

the aircraft wa finally in ombat use

with the U AAF during 1943 it did not

take American pilot long to realize the

Mustang's xcellent capabilities, which

must have led many of them to wonder

why the RAF had already operat d the

Allison-engined Mustang for a whole year

before the U force took the type into

combat. ome of the i u relating to that

delay are explored in thi book, but it i

part of a debate that will no doubt con-

tinue for many years into the future.

This book end avours briefly to tell thc

Mu tang's story, in addition to touching

on ome of the 'myths' about the type,

while exploring technical and operational

a pects that are often overlooked in other

published source. Some publi ations in

the past have followed each other' lead

on some of the establi hed 'fact' about

the Mustang, which have passed into the

aircraft's mythology while in truth not

being corr ct in the first place. The myth

of the 'British 120 days r quirement' for

the creation of the Mu tang prototype,

often repeated in publi hed ources, falls

into this category, as doe so-called'infor-

mation' on foreign-operated Mustangs. It

is amazing, for example, to see how many

published sources follow each other in

claiming that the Italian armed forces

operated forty-eight Mu tangs after the

econd World War, when the reality, as

explained in this book, is that th Italians

operated approximately 173 Mu tangs at

one time or another! It is therefore hoped

that thi book represents the most up-to-

date, genuine research on the Mustang,

hased on the study of original documen-

tation and the thorough investigation of

dcdicated individual noted below.

Acknowledgements

As ever, it is a pleasant exercise to

acknowledge friend and colleagues

whose as istance and advice have made

such an invaluable contribution towards

the piecing together of much of the infor-

mation and photographic content of this

hook. A number of specialist in th ir

particular field were especially helpful,

mcluding Richard L. Ward, Jerry cutts,

Chris Ellis and Mark Rolfe. Dick Ward

was particularly supportive in pointing

my ever-growing number of enquiries in

the right directions, and in his great

assi tance with photographs and illustra-

tions. Considerable help was Similarly

rendered by John Batchelor, with infor-

mation, photographs and sources.

A very special word of thanks is due to

Jcrry Day of Oklahoma City in the A.

Jerry and his team look after the famous

racing Mustang Miss America on behalf of

Dr Brent Hisey, and I particularly express

thanks to Jerry, Dr Hisey and the whole

Miss America team for their invaluable

help, not just with background material

on racing Mustangs, but also on many of

the technical aspect of the Mustang and

its operation. Jerry Day was additionally

of great help with checking Mustang facts

and figures in my text.

From among my 'local' circle of aero-

nautical colleagues, special mention

must go to Tony Blake, Tony Brown,

Dave Clark-Wheeler, Ian laxton, Pete

Clifford, Derek Foley, John eale, Jim

mith,Andy weetand lifford Williams.

Particularly helpful was an expert local

to me on many aspects of the United

tates Army Air Corps (USAAC) and

USAAF, Gordon Stevens, who opened

his vast archive of -related informa-

tion and photograph specially for this

project. Several friends from elsewhere in

the UK were also involved w ~ assisting

this project, including Mick Gladwin of

www.airrecce.co.uk, and ick troud of

Aemplane MOllthly magazine, who also

liaised with former RAF Mustang pilot

Colin Downes on my behalf. Les Wells

of the IPMS-UK Eighth and Ninth Air

Force Special lntere t Group similarly

suppl ied excellent information and reF-

erences. pecial thanks must also go to

Richard Haigh, latterly of the Rolls-Royce

Heri tage Trust.

Help has come from all corners of the

globe in the form of information, photo-

graphs and background information on

the Mustang in its many guise and areas

of service. Particular individuals include

Graham Lovejoy in ew Zealand; recko

Bradic in erbia; Miroslav Khol and

Pavel Jicha in the Czech Republic; a

large number of American friends includ-

ing Bob Avery, cott Hegland and Jack

McKillop, together with Ron Kaplan of

the U ational Aviation Hall of Fame,

and ancy Parri h of the Wings Acro

America organi ation in remembrance of

women pilots in the USA during World

War Two; Jean-Jacques Petit in France;

Peter Walter, 'Misty', and colleague in

Germany; and my many friends in anada,

including William Ewing, Patrick Martin

and particularly R.W. (Bill) Walker, whose

knowledge of Royal anadian Air Force

(RCAF) Mustangs is encyclopaedic. Also

e pecially helpful in the latter country

was Ron Dupas, who assisted with many

lead and photographic sourc s through

his website www.l000aircraftphotos.com.

I am similarly indebted to Christopher C.

larke, whose father, Fit Lt Fred 'Freddie'

Clarke, was involved in th air battle

on 19 August 1942 near Dieppe, during

which Fg Off Hollis Hill of 414 Sqn,

RCAF, hot down the first enemy aircraft

ever credited to a Mustang.

I am indebted to everal historians

who maintain web site on the Internet

that are a valuable re ource of genuine

research and photography relating to the

history of the Mustang. In particular, my

Swiss friend Martin Kyburz made avail-

able to me his extensive knowledge of

wiss-operated Mustang, in addition to

the wealth of information that he has on

many other aspect of the Mustang's devel-

opment and service. Hi web ite www.

swissmustangs.ch is a fantastic resource

for Mu tang enthusiast and historians.

incere thanks mu t also go to Peter

Randall, whose xcellent web site www.

littlefriends.co.uk contains a goldmine of

d tailed information on US Eighth Army

Air Force fighter units and their aircraft

and pilots. Peter generously supplied pho-

tograph and much background informa-

tion on this fascinating subject.

A great deal of the reseal' h relating to

the creation of the Mustang wa under-

taken in the ational Archives at Kew,

London, and thanks go to thi body for

7

these excell nt facilities. This depository

holds a con iderable amount of documen-

tation concerning the British purchasing

effort in the U A from 1939 onward.

There ar many letters and other docu-

ments relating specifically to the birth

of the Mustang in the ar hive at Kew,

and the e also confirm the name of the

body that Britain e tabli hed in the A

in late 1939 to pelform the buying of

war material, the Briti h Purchasing

ommission.

A number of veterans' association

also provided great help and advice.

The e include the 339th Fight r Group

A sociation ( tephen C. Ananian), the

20th Fighter Wing Association (Arthur

E. evigny) and that of the 55th Fighter

Group (Russell Abbey). Unfortunately

some veterans' groups are not 0

willing to deal with Briti h hi torians, but

the aforementioned are excellent organi-

zations with a sense of the significant

history that they represent.

A special 'thank you' must be made

to apt Eric Brown, who contributed

the foreword for this book. Rightly on

of Britain' most renowned pilot of the

World War Two era, apt Brown has a

unique knowledge of the Mustang, having

te t-f1own examples of the aircraft at the

time. Along with the upermarine pitfire

and the Focke-Wulf Fw 1900-9, he con-

sidered the Mustang one of the top three

fighters of the econd World War.

ad to relate, during the writing of

this book three per onalitie pa ed away

who were each very much a part of th

Mustang story in their own particular

respects. All three were assisting with

this proj ct, which makes their pas ing

all the more regrettable. They were the

famous historian Roger A. Freeman,

whose writing on the U AAF in World

War Two is legendary; Paul Coggan, who

was the mo t knowledgeable resear her

on Mu tang restoration and the 'warbird'

cene relating to Mustangs; and Brig Gen

Robin Olds, Mustang fighter pilot from

the 479th Fighter Gr up and econd

World War and Vietnam War veteran.

All three are sadly missed.

The work of wri ti ng th is book took place

over more than three years, and during

that time considerable a istance wa ren-

dered with the checking of text and facts

by Lucy Maynard and by my father, Victor

Lowe, himselfan aviation historian oflong

tanding. imilarly deserving of thanks is

the staff of my publi her, The Crowood

Press, for their patience and very profe -

sional assistance during th preparation of

this book.

As always, constructive reader input

on this volume would be most welcome.

Comments, information, suggestions and

photographs can be communicated to the

author at 20, Edwina Ori ve, Poole, Dorset,

BH17 7JG, England.

Malcolm V. Lowe.

Poole, Oor et, June 2009.

Author's note

All prices in the text that are quoted

in dollars ($) refer to US dollars unle

INTRODUCTIO AND ACKNOWLEDGEME T

otherwise noted. The titles of US Army

Air Corps, US Army Air Force, and U

Air Force units are taken from the official

US government documents relating to

unit activations, nomenclature and dates

of service, as condensed in the official

reference books edited by Maurer Maurer

and referred to in the Further Reading

ection at the end of thi book. The

unit name quoted in this book therefore

sometimes differ from those given in some

published sources, but those quoted here

are absolutely correct as given in official

documents for the times and dates under

discussion.

The aerial scores achieved by fighter

'aces' of the U services are those given in

the book by Frank Olynyk (again quoted

8

in thi b ok' urth r Reading section),

which ar imil rly t k n from official

ource, n th in d viate in some

ca es from h m whc t more 'populist'

and less w II h k d information quoted

by some U writ r .

Where po ible, II pia n mes reflect

local spellings, but it i a kn wi dged that

some location have hang d th ir name

subsequent to th tim th t Mu tangs

were a sociat d with th m. Th re are also

limitation within th printin proce s for

the reproduction f om reign letters

and charact r. om pe ifi locations,

for example ox' Bazar in India, have

rejoiced with more than on pos ible

spelling (in this case, an alt rnative i

Cox's Bazaar).

By Captain E.M. 'Winkle' Brown CBE,

o C, AFC, MA, R

Former Commanding Officer, Aero-

dynamics Flight, RAE Farnborough

Mustang: a word evocative of a wild

creature with unbridled speed and power.

The aeroplane of that name was born

in California in 1940, having been con-

ceived by orth American Aviation and

fathered by a British necessity. In its

early life it showed great promise at low

altitude, but needed an engine transplant

and a considerable mak -over to convert

it into the magnificent Merlin-engined

laminar-flow-winged fighter it became,

Foreword

in time to provide effective escort for

the daylight bombers striking the Third

Reich.

I flight-tested virtually every Allied

and enemy fighter in World War Two,

and rated the Mustang later models in the

top three alongside the pitfire and the

Focke-Wulf Fw 1900-9. I certainly con-

sidered it the finest escort fighter of World

War Two. What distinguished the Merlin-

engined Mustang was its performance

in the transonic region of flight, which

enabled it to give effective high cover to

the high-flying B-17 Flying Fortresses.

Obviou Iy there is still a great deal of

interest in the P-51 Mustang, which is

even now flying in significant numbers at

9

air shows and competing in pylon racing.

It has therefore generated a number of

books, but not every a pect of its story has

been covered. The author f this book

has set out to fill in some of the gaps and

whet our appetite with a somewhat differ-

ent approach to the subject, which readers

should find much to their liking. 1was par-

ticularly delighted to find some data on

the Twin Mu tang as well, as this aircraft

has always intrigued me. That is the kind

of book it is. Enjoy it'

Captain E.M. Brown

West Sussex

August 2008

Historical Perspectives

It could all have been very different.

At several significant stages the whole

project that led to the Mu tang could

have been derailed or even ended alto-

gether. Indeed, were it not for individual

initiative, forward thinking, and at times

downright audacity, the Mu tang might

never have been created, or developed

into the excellent aircraft it became. To

put the story of the Mustang into his-

torical perspective from the outset, the

creation of this excellent aircraft had

many of it roots in developmel,ts that

trace back to the accession to power of

Adolf Hitler and the National ocialist

( azi) party in Germany during early

1933. The Nazi rise to power was fol-

lowed by an unprecedentcd period of

military expansion in Germany' armed

forces. A significant part of this was the

rapid growth in Germany's air force, the

Luftwaffe, a factor that had been forbid-

den in the peace ettlement at the nd

of the Fir t World War. The existence of

the new Luftwaffe wa publi Iy acknowl-

edged in Mar h 1935, and it cam a

a very unwelcome developm nt for

many neighbouring European countries.

Indeed, Germany's significant military

expansion, coupled with an increasingly

aggressive foreign policy that was pur ued

by the azi leader hip, led to a com-

pletely changed reality for the countrie

of Europe. The respon e of ome, par-

ticularly Britain and France, was to fool-

ishly indulge in the appea ement of the

Nazi leadership and its aims. Fortunately

th re were sufficicnt wise heads in both

Britain and France who realized that such

a policy had no chance of su s, and wa

in any case absolutely morally and mili-

tarily bankrupr. Reluctantly a policy of

rearmament wa commenced during the

1930 by a number of European countrie ,

but in most cases thi represented little

more than a case of catch-up with the

high quality (both in terms of numbers

and increasing capability) of rearmament

ers, the period from the mid to late 1930s

onward proved to be an age of unrivalled

opportunities, in which rapidly developing

and expanding military requirements and

massive production possibilities became

a reality after years of comparative stag-

nation of military orders in the post-Fir t

World War period. The potential existed

during that era for aviation companies to

grow out of all proportion to their pre-war

size, and with that growth came substan-

tial increa e in the numbers of people

employed in aviation-related activities,

and the development of a highly-skilled

and motivated workforce. That this came

about after the difficult times following

the economic crises of the late 1920s and

early 1930s was little short of a godsend for

the aviation bu iness. They were unprec-

edented times for the growth of aviation,

and out of the world crisis that took the

form of the econd World War many sig-

nificant aircraft types emerged. Some of

these have become legendary and rightly

hold a very special place in the hi tory

of military aviation. The Mustang is one

of those very special air raft, and it was

without doubt a significant contributor to

the final Allied victory in 1945.

The company symbol of North American Aviation.

Inc. NAA

Creating a Legend

CHAPTER 1

Many superlatives have been written

about orth American Aviation' P-51

Mustang. At the time of its greatest

moments in the latter stage of the econd

World War, and in the decades following

that time, it came to be regarded as a war-

plane virtually without equal. Celebrated

hy many, and with a war record that fcw

other combat aircraft of its own time

or ince have been able to match, the

Mustang tends to stand head and shoul-

der above many of it contemporarie,

and was undoubtedly on a par with the

vcry best of its breed. It wa an aircraft

that proved capable of effectively per-

forming a variety of roles, and in some

of these tasks it truly excelled. Mated

eventually with the equally admirable

British Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, the

Mustang evolved into probably the finest

escort fight I' of all time, and proved to be

a godsend to the very service that at first

had seen little use for it, the U AAF. It

wa a remarkable aircraft, and imilarly

It had an equally remarkable creation

and development, that in many respects

went completely against the trends and

customs of its time.

The Mustang became an indispensable

part of the Allied war effort as World War

Two progressed, in what was probably

the great st aerial struggle that the world

has ever seen. Military aviation played

a vital role in many diverse ways during

that immense conflicr. All of the major

combatants fielded significant numbers

of combat aircraft, and the indispen able

nature of military aviation was unques-

tionably e tablished by the war's end.

Warplane design and development, and

manufacture, moved forward in leaps and

bounds during the war, continuing the

trend of te hnological advances in aero-

dynamics, materials and powerplant tech-

nology that had arisen during the 193 s.

The Mustang in many ways represented

the pinnacle of piston-engined fighter

development, before thc jet-powered

combat aircraft took over forever.

For aircraft designers and manufactur-

- .----

-,

IO'-6"PROP. DIA.

1

;'

/

----j-

---or

.. !

1---------------37'-fil SPAN

C

73

2

~ ~ r e =

- - .... #--.-

lOlllCLEARANCE

2 i

--'----------.,----

r ~ .

1-----142"

This very early NAA drawing from the first half of 1940. showing a proposed NA-73 layout, illustrates major similarities with the aircraft that was eventually built

and some notable differences. Particularly noteworthy are the very streamlined cockpit cover; the neat installation of the Allison V-1710 inline engine. keeping

frontal area to a minimum; and the famous underfuselage air intake for the mid-fuselage radiator. NAA

11

that wa rapidly taking place in azi

Germany. The achievem nt of German

warplane and their skilled and highly-

motivated pilots during the panish Civil

War, which concluded successfully for

the Fascist powers in March 1939, ilIus-

trated how far German aerial capability

had come in such a hort space of time.

In Britain, the RAF embarked on an

'expansion scheme' that aw a significant

influx of more 'modern' combat aircraft

to replace the colourful but increasingly

outmoded biplanes that were in front-line

British service well into the 1930s. Britain

in fact had everal important advantages

over many other countrie , not least of

these being a pool of talented aircraft

designers who were not afraid to embrace

progress and new concept in aircraft

design and materials. This, coupled with

advances that had been made by partici-

pation and eventual overall succes in the

chneider Trophy contest from 1919

to 1931, helped put Britain among the

leaders in the field in everal key area of

aircraft design and powerplant technol-

ogy. ew ways of building aircraft were

al 0 coming to the forc during the 1930 .

Important among these was the increa -

ingly widespread adoption of all-metal,

stressed- kin construction in warplane

design and manufacture. Metal aircraft

were not new even at that time, the first

successful metal military monoplanes

having flown during World War One, but

in several countrie the all-metal mono-

plane fighter wa coming to the fore and

sweeping away the fabric-covered biplane

fighter for ver. Other advances, uch

as the adoption of retractable undercar-

riages and enclosed cockpits, were leading

to warplanes of increa ed capability that

little resembled the front-line types of

just a few year previously. Reginald J.

Mitchell's beautiful, iconic upermarine

pirfire and ydney Camm's rugged, pur-

po eful Hawker Hurrican (which admit-

tedly till retained fabric covering in its

construction) were the be t that the free

world had to offer in response to German

rearmament that included the highly

important Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter.

Both the pitfire and the Hurricane were

powered by the Rolls-Royce Merlin inline

engine, later to have such a significant

impact on the tory of the Mu tang.

The probl m for Britain was that both

the pirfire and the Hurricane were not

necessarily going to be enough by them-

selves, particularly in terms of number,

to face the tide of a German aerial

assault against Britain and her allies. The

Hurricane first flew in November 1935,

and wa well establi hed in RAF front-

line service in September 1939 when the

Second World War began. The Spitfire

made its fir t flight in March 1936, and

began to enter front-line squadron service

with the RAF in the latter halfof 193 . By

that time the Luftwaffe' Bf 109 had b en

in service since 1937, and had proven it

worth in combat over pain from 1937

onward. Early models of the Bf 109 were

powered by the Junker Jumo 210 inline

piston engine, but just coming into wide-

spread Luftwaffe service in 1939 was the

Daimler Benz DB 601-powered Bf 109E,

the deadl ie t of the breed up to that point.

Britain, like all other European countri s,

was becoming acutely aware of her lack

of significant numbers of fighter aircraft

in depth that were capable of taking on

the Bf 109, and the growi ng array of other

high-performance Luftwaffe aircraft that

would be involved in any general conflict.

evertheless, ev n though Britain was

faced with the need to catch up, particu-

larly in terms of numbers of modern war-

planes, she was far b tter placed than any

other alii d country in Europe to take on

the Luftwaffe because of th RAF's growing

numbers of pitfires and Hurricanes. 0

other We tern European country could

boast anything like either the pitfire or

the Hurri ane in their inventorie , and

everal other key allies, such as France,

were struggling to bring modern de igns

to the fore after years of tagnation in offi-

cial specifications and long delays in the

creation of modern designs. The Munich

Agr ement of September 1938, which

ceded ignificant partsofone ofBritain and

France' all ies, Czechoslovakia, to azi

Germany was suppo ed to end Germany'

territorial ambitions. The German take-

over of the remainder of zechoslovakia

in March 1939 showed that Munich was

simply another debacle, and even Britain's

inept and weak government realized that

the game was up and the azi threat had

to be confronted.

Supplies from

the United States

In reality, however, a large expan ion in

Britain's armed forces, over and above

what was already being achieved, wa

likely to further overburden Britain'

12

re ource. notherourcc of war mate-

rial had to b found, to try and bridge

rapidly the num ri al and quality gap

that exi ted b tw en mu h of what the

Western allic had in rvi e compared

with th growing azi war machine. The

obvious and indeed the only substantial

potential out ide ourc wa the USA. A

number of Eur pean countrie , including

Britain, establi h d official purchasing

organization to vi it the A and work

along ide their exi ting diplomatic cover

to place order with American ompanie

to upply war mat rial as oon a po ible.

It must be tressed here that the shop-

ping list for these pur ha ing agencies did

not just include Fighter aircraft. Britain

was well behind by the later 1930s in

rearmament in just about every military

requirement, and combat aircraft of all

type, train r and second-line types, in

addition to other war material including

armoured fighting vehicle and warships,

were a top priority. The whole idea of

foreign delegation placing ord r with

American companies to supply war mare-

rial was, however, omething of a compli-

ated concept.

On the one hand, Ameri an indus-

try generally welcomed th considerable

financial opportunities that the e poten-

tial orders represented. On the other

hand, the U A did not officially consider

itself involved in what appeared as the

1930s wore on to be a European quab-

ble. Much is usually made of America's so-

called 'isolationism' during that p riod. In

fact the A's foreign policy was much

more complicat d than the often-quoted

'isolationist United States'. President

Franklin D. Roosevelt wa rather more

level-headed than some members of the

American ongress, and realized that the

U A could not tay aloof from the signifi-

cant problem that were developing in far-

away Europ , whether that would be in the

long-term intere t of the U A or nor. The

U A in effect had global int r ts even

at that time, with significant attention

being placed on the Panama anal Zone

in entral America and in the Eacific area

c ntred on Hawaii but also including th

Philippines, to name but two significant

areas of overseas concern. In reality the

American government tended to turn a

blind eye to many of the activities of the

foreign delegations that spent an increas-

ing amount of time in the late 1930

negotiating with some areas of American

industry, and often striking up very good

relation. evertheless, some American

companie were much les than willing to

deal with the foreign purchasing organiza-

tions, and there were certainly many in

the USA who were unhappy at Ameri a

being involved in any way with the devel-

oping problems in Europe at that time. It

was therefore somewhat fortunate that

the British purchasing representatives in

particular were able to develop excellent

working relationships with everal key

American armaments companies. It wa

here that the story of the Mustang began

to take shape.

One of the significant early purchases

of aircraft that was made by British repre-

sentatives was a major order for the North

American NA-16 trainer series. This

tandem two-seat training aircraft was an

early product of a comparatively new U

company, North American Aviation, Inc

( AA). Originally formed in 192 simply

as a holding company for other aviation

concerns, from 1934 NAA became a

designer manufacturer in its own right,

and had started with the considerable

weight of the General Motors organiza-

tion behind it. The company's manufac-

turing division had originally taken on th

factory pacc of the formcr Bf] Aircraft

Corporation and Gen ral Aviation

Manufa turing Corporation organization

at Dundalk, Maryland, which had been a

part of the grouping from which the new

AA emerged.

The first entirely original design from

the new company wa an open-cockpit,

tandem two-seat single-engine fixed-

undercarriage train r monoplane, built a

a private venture to meet a basic trainer

requirement for the U AAC. The pro-

Unfortunately, many of the world's great aviation com

panies have lacked longevity. Although a small number

from the pre-Second World War era survive today, few

remain in their original or nearoriginal form. One of

those that has not survived to the present is, regrettably,

the dynamic company that created the P-51 Mustang,

although its lineage can be traced, albeit tenuously, to

one of today's aviation giants.

North American Aviation, Inc. existed as a major

aircraft producer for only just over three decades, but

in that time it gave birth to some of aviation's classic

aircraft. To understand the creation of this significant

company it is almost as important to comprehend the

workings of American corporate big business as it is

to have a knowledge of US aviation history in general

during the period between the two world wars. Aviation

totype Wright R-975 engined A-16,

registration X-20 0, first flew on I April

1935. Its test pilot was Eddie Allen, who

later found fame performing flight testing

for Boeing but tragically lost his life in

the crash of the second Boeing XB-29

uperfortre bomber prototype on 1

February 1943. In the event, AA was

not sub equently the front runner in the

trainer competition, which wa in e ence

won by a contender from eversky. Th

Sever ky design duly gained production

order as the BT- , and was thefi r t ai rcraft

type specifically created a a ba ic train r

r the U AA . However, significantly,

the con iderable influence of General

Motor h Iped to give the A-16design

nough wight to secure USAAC orders

additional to the Seversky model. After

some design modification the initial pro-

duction derivative of the NA-16, called

BT-9 by the U AA , was Fir t flown by

te t pilot Paul Balfour on 15 April 1936.

The ba ic d ign attracted significant

orders for the time, and AA's produc-

tion facilities were already being trans-

ferred from Dundalk to larg r premi e in

southern California on the w t coa t of

the USA. These took the form of major

factory space on the southeastern dge of

Mines Field, the Los Angeles Municipal

Airport at Inglewood, on the out kirts

of Los Angeles, which today is a part of

the sprawling Los Angele International

Airport. The company ucce fully nego-

tiated an excellent deal for the lease of

the location (the whole ite eventually

covered some 20 acres), which was avail-

able for only $600 each y ar. At first using

an existing factory (known locally as the

Moreland building), the beautiful new

North American Aviation: a Brief Company History

started to become an important business in the USA

around the time of the First World War, when large

military contracts began to hold the promise of con-

siderable financial reward. True, the original aviation

pioneers such as Orville and Wilbur Wright had sought

to sell their new creations, but it was the appearance of

shrewd businessmen who also understood the develop-

ing science of aviation engineering that led to the growth

of aviation as a potential money-spinner. Pioneers such

as Glenn Curtiss, Donald W. Douglas and others became

very important in the development of the aircraft industry

as a significant business in the USA, but behind many

aviation pioneers were financiers who knew little of

aviation but understood much about making money. It

was out of these circumstances that NM first emerged.

The company that eventually grew into the NM of

13

tate-of-the-art factory it If opened for

production in early 1936, and the AA

entry in Jane's All The World's Aircraft of

1937 pointed out that the plant covered

an area of 172,000 square feet, although

this was extended during 1937 to 380,000

square feet and later saw further growth.

The move to California was an out-

standing step forward for NAA. The

often fine weather in the Los Angeles area

allowed many uitableday offlight testing

that were not interrupted by bad weather

(although even southern California is not

immune to occasional freak weather, such

as the snowfall th re in 1944). When large

orders were r ceived for later types such

as the P-51 Mustang, some final a sembly

work was actually performed out ide in the

open air, in addition to th bu ya embly

lines within the factory complex itself.

An increasingly well-trained and numer-

ous workforce was also readily to hand in

the Los Angele and southern California

area. It is little wonder that a number of

aviation companies gravitated to this area

when the wor t effect of the financial dif-

ficultie of the late 1920s and early 1930s

and the subsequent ecunomic depression

began to wear off.

The establi hment of NAA a an air-

raft producer in it own right al 0 saw an

influx of key high-level per onnel who

were to shap the destiny of the company

and it product in the coming years. At

the head of this developing team was

J.H. 'Dutch' Kindelberger, who became

President ofNAA and general manager of

its manufacturing division. Kindelberger

was an astute businessman with an avia-

tion background that included work with

two giants of the US aviation industry,

World War Two could trace its lineage back to 1928.

Created in December of that year, the original North

American Aviation Inc. was born as little more than a

paper organization. Its founder was Clement M. Keys,

a wealthy financier who was developing an impressive

portfolio of aviation companies within his expanding

business empire. Rather than being a faceless man of

money, however. Keys was well known for his steward-

ship of the world-famous financial publication The Wall

Street Journal. The NAA that he created in 1928 was not

an aircraft manufacturer, but was more or less aholding

company for the various aviation concerns within his

growing aviation empire. These included airlines with

names such as Eastern Air Transport, Transcontinental &

Western Air, and Western Air Express, and aircraft man-

ufacturers such as Berliner-Joyce. For a time Keys was

CREATI G A LEGEND

The company that was eventually named North

American Aviation came about as a result of

corporate restructuring and various mergers

in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The grouping

out of which NAA was born included the old

Berliner-Joyce Aircraft Corporation, which had

produced the P-16/PB-1 series of fighters for the

USAAC, typified by the Y1 P-16/PB-1 shown here,

powered by a 600hp Curtiss V-1570 Conqueror

inline engine which gave it a top speed of

some 175mph 1282km/h) at 15,OOOft (4,570m). The

original prototype was ordered in 1929 and, in

corporate terms, this biplane fighter was the

predecessor of the Mustang.

USAAF via Gordon Stevens

As iconic to the jet age as the Mustang is to the

era of piston-engined fighters, the beautiful and

highly successful North American F-86 Sabre jet

fighter was built in a variety of different versions

for the USAF, USN and many overseas buyers.

The first flight was made in October 1947 by

famous NAA test pilot George Welch. The type is

represented here by the first production P-86A,

soon renamed F-86A, 47-605, an Inglewood-built

F-86A-1-NA powered by a General Electric J47

turbojet of 4,8501b thrust. It is shown here on

an early test flight, still wearing the original

'Buzz Number' prefix for the Sabre of 'PU', later

changed to 'FU'. NAA

CREATING A LEGEND

North American Aviation designed and produced

a succession of highly-successful aircraft

types that became legends in their own right.

One of these was the TexanIHarvard family

of military trainers, one of the most famous

training aircraft types of the Second World

War. This example was iicence-built in Canada

by Canadian Car & Foundry and delivered in

December 1952 to the RCAF. Officially a North

American NA-186 Harvard Mk.4120454, GO-454),

it served with various Canadian units including

the Flying Instructors' School at Moose Jaw

Saskatchewan, Canada, where it is believed

have been operating when this photograph was

taken. It was retired in November 1964, showing

the longevity of many of NAA's products.

RCN via Ron Dupas

North American Aviation made a foray into

jet bomber design with its B-45 Tornado, the

prototype of which first flew in March 1947.

The type was not a great success, its four

4,OOOlb-thrust General Electric J47 turbojets and

straight rather than swept wings resulting in a

pedestrian performance that saw the B-45 soon

relegated to reconnaissance work. The more

powerful reconnaissance-dedicated RB-45C

Tornado played a useful part in the Korean War.

Illustrated is the first production B-45C bomber,

48-001. USAF

14

In medium-bomber terms the North American

B-25 Mitchell was as significant as the Mustang

was to fighter operations, having fighter-like

speed and manoeuvrability coupled with heavy

firepower. Built in several versions, the Mitchell

was a great success in World War Two, the

design that led to the B-25 having flown for the

first time in its original form during January

1939. Illustrated is a USAAF-operated B-25G in

anti-submarine camouflage. The 'G' version had

a 75mm M4 cannon in its short 'solid' nose along

with two 0.5in machine guns, the 75mm being one

of the heaviest forward-firing weapons mounted

in a production aircraft during the war. USAAF

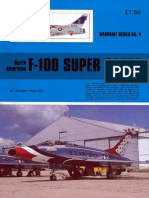

A contender alongside the Soviet Union's

MiG-19 for being the first genuinely supersonic

jet fighter to enter front-line service, the North

American F-100 Super Sabre was a highly

significant fighter in the development of high-

performance jet combat aircraft. The prototype

first flew in April 1953, and exceeded the speed

of sound on that first flight. The first of two

YF-100 prototypes is illustrated, showing the

type's sleek and purposeful lines. Initial F-100A

production examples were powered by a single

Pratt & Whitney J57 turbojet of some 15,OOOIb

thrust with afterburning, making the F-100 one of

the first successful users of a high-performance

afterburner-equipped turbojet engine. USAF

15

also associated with several big names including Curtiss

and Douglas. Berliner-Joyce was a creator and manu-

facturer of biplane fighters for the USAAC (P-161, and

observation biplanes for the USN (OJ-21. Reorganization

of the Berliner-Joyce Aircrah Corporation aher it was

taken over by NAA in 1930 had created the B/J Aircrah

Corporation, with offices at 1775, Broadway, New York,

and manufacturing premises at Dundalk in Maryland.

These times were not good for aircrah companies,

however, due to the financial disasters of the late 1920s

and the subsequent Depression.

In 1933 NAA was merged with a separate organiza-

tion, the General Aviation Corporation (GACl, the latter

being the holding company for the aviation interests

of the giant General Motors Corporation. The GAC con-

tained within its own organization the General Aviation

Manufacturing Corporation (GAMCl, formerly the Fokker

Aircrah Corporation of America. Soon the manufacturing

parts of each business were consolidated at Dundalk,

Maryland, and the GAMC built some rather undistin-

guished designs such as the G.A. F-15 twin-engined

monoplane flying-boat for the US Coast Guard, and the

G.A.43 single-engined low-wing ten-passenger airliner.

This arrangement did not last long, however, for in 1934

a major reorganization took place, in which General

Motors relinquished some of its hold on the whole

General Aviation organization, which included both air-

lines and manufacturing capacity, due to a new federal

law that required manufacturers to be manufacturers

alone, and not operators or airmail contractors as well.

This leh the way open for a new North American organi-

zation to arise as a related but separate entity. In 1934

the new North American Aviation, Inc. was born, with

its offices in the old B/J Aircrah Corporation's premises

at 1775, Broadway, New York, and with its own manu-

facturing division at the previous Dundalk facility of B/J

and the GAMC. The General Motors influence was still

highly important. and the first chief of the new NAA was

a General Motors man, Ernest Breech.

Everything went very well from the first for the new

organization. Brought in almost straight away to be the

new president of NAA and general manager of its manu-

facturing division was talented businessman and experi-

enced aviation manager James H. 'Dutch' Kindelberger.

Under his guidance, together with the talented team

that he assembled around him, NAA grew from strength

to strength. From the first, the new company intended to

design and manufacture its own, new designs as soon

as practical. Initially NAA built the 0-47 single-engine

observation monoplane for the USAAC, which owed

some of its design to the period immediately before the

birth of the new NAA. The first entirely original design

of the new company was an open-cockpit, tandem two-

seat single-engine fixed-undercarriage trainer mono-

plane called the NA-16, which developed and grew into

the hugely successful AT-6 Texan/Harvard series of

trainers that were so important to Allied pilot training

in World War Two, and served worldwide in a large

number of air arms. Not long aher its creation, NAA

began to move its manufacturing premises from the

grey skies and limited growth potential of Dundalk to

the blue skies and massive growth potential of southern

California. The choice of location for NAA was the

Los Angeles Municipal Airport, othervvise known to

CREATING A LEGEND

the locals as Mines Field, in the Los Angeles suburb

of Inglewood. This site in itself is one of the world's

famous aviation locations. Selected in June 1928 to be

the new Los Angeles Municipal Airport from a shortlist

of contenders, the airport grew from small beginnings

and limited infrastructure into one of the world's major

airports. Renamed Los Angeles Airport in July 1941 (but

still known locally for many years as Mines Field, aher

the real estate agent who negotiated its sale to the city

of Los Angeles in the 1920s1, it saw massive growth in

the post-World War Two period. Aher being renamed

Los Angeles International Airport in 1950, a completely

new airport was built on the site in the late 1950s and

early 1960s, much of which still remains. Today it is one

of the world's great airports.

When the NAA's manufacturing division relocated

from Dundalk to Mines Field in 1935 it temporarily

used a structure known as the Moreland building, but

soon a new purpose-built and state-of-the-art factory

was built there on land leased from the Los Angeles

Department of Airports. This new factory was running

in early 1936, and construction of NA-16 series trainers

soon took precedence. However, NAA was a young,

ambitious company. Through the excellent relationship

that it developed with British purchasing representa-

tives over the acquisition by Britain of NA-16-series

trainers, the seeds were sown that led to the creation

of the Mustang. In addition, NAA developed a twin-

engine medium bomber, the NA-40, which grew into the

highly successful B-25 Mitchell that saw widespread

service in World War Two. So successful was NAA that,

despite massive expansion, the capacity of the factory

at Mines Field was fast being outstripped by growing

orders at the end of the 1930s and start of the 1940s.

So NAA developed two further production plants, one

at Kansas City, Missouri, which subsequently principally

manufactured B-25s, and one at Dallas, Texas, where

AT-6 Texan/Harvard manufacture initially took place,

joined by overspill production of P-51 s later in the war.

The Dallas site was not in Dallas itself, but was situated

at Hensley Field in nearby Grand Prairie. Construction

of the new factory began in the latter half of 1940, but

the transfer of production of the AT-6 series from Mines

Field to Dallas seriously slowed aircrah production until

the spring and summer of 1941. Nevertheless, NAA's

factories were built around the successful, modern and

efficient moving production line, and large numbers of

Mustangs, Mitchells, Texans and Harvards were manu-

factured during the war. This massively expanded NAA's

workforce, from an initial total of some 180 in the mid-

1930s to approximately 91,000 late in the Second World

War. Later in the war the unusual P-82 Twin Mustang

began to take shape at Inglewood as an answer to the

need for a very-long-range fighter escort. The company's

wartime output was huge, the 30,OOOth NAA aircrah

since the start of wartime contracts in the summer of

1940 being a Kansas City-built B-25J It is all the more

remarkable that all of these designs were exceptional

machines, each one being the top of its respective

combat role and better than its US rivals.

The success of the Mustang, AT-6 Texan/Harvard

series and B-25 Mitchell propelled NAA into the ranks of

America's premier aircrah manufacturers. The success

continued aher the end of the war. The coming of the

16

jet era saw the company fully engaged in the develop-

ment of a new jet fighter, the work beginning during

the war years. Initially flying in October 1947, the XP-86

prototype was the forerunner of the first operational

swept-wing jet fighter in the western world, the superb

F-86 Sabre. Arguably as iconic as the Mustang, the

Sabre fought its own successful war in the skies over

Korea in the early 1950s. In addition NAA produced the

first-ever production jet bomber for US service, the B-45

Tornado, which also went to war over Korea, but as a

reconnaissance aircrah. A new division at Columbus,

Ohio, produced some of the F-86 production run and

worked on other programmes, although General Motors

eventually pulled out of NAA ownership. So successfully

did NAA make the switch to jet-powered combat aircrah

that it also created the F-l00 Super Sabre, which holds,

with the Soviet Union's Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-19, the

record for being the first supersonic jet fighter to reach

operational service. Other NAA designs included the

A3J/A-5 Vigilante carrier-borne supersonic strike and

reconnaissance aircraft, the T-28 Trojan trainer (a suc-

cessor to the ubiquitous AT-6 Texan/Harvard familyl,

the USN's T-2 Buckeye jet trainer, the OV-l0 Bronco

light-attack and COIN aircrah, and the incredible Mach

3-capable XB-70 Valkyrie bomber prototypes, the first

of which initially flew in September 1964. The company

also increasingly became involved with rocket technol-

ogy as the 1950s progressed, developing its Rocketdyne

division and building the amazing X-15 air-launched

supersonic research aircrah.

Unfortunately this success did not last for ever. On

22 September 1967 NAA merged with the Rockwell-

Standard Corporation of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to

create the North American Rockwell Corporation. A

major reorganization took place in 1971, the corpora-

tion being divided into several constituent parts, one

of which was the North American Aerospace Group.

This was replaced, in February 1974, by two organiza-

tions, the North American Aircrah Group and the North

American Space Group. The former duly continued work

on a significant aircrah type that is still very much

with us, the B-1 Lancer swing-wing bomber (first flight

December 19741. The latter was involved in significant

space programmes, the most high profile of which

was the development and manufacture of the Space

Shuttle.

Sadly the name North American eventually disap-

peared. In February 1973 North American Rockwell

changed its corporate name in a further reorganiza-

tion, becoming the Rockwell International Corporation.

Nevertheless, the North American name was still asso-

ciated with various programmes into the 1980s, one of

these being the development of a new version of the

gunship family based on the Lockheed C-130 Hercules

transport, the AC-130U Spectre, the first conversion of

which flew in December 1990. By that time the NAA

branch of Rockwell had facilities in Palmdale, California,

and Tulsa, Oklahoma. Everything changed, however, in

December 1996. On 6 December 1996 Rockwell was

purchased by aerospace giant Boeing for $3.1 billion.

Interestingly, for a short time aher this the name Boeing

North American was used for the newly-created entity,

but it was not long before North American Aviation's

name was gone for ever.

Glenn Martin and Donald Douglas. He

had latterly worked a a vice-president for

engineering with the Dougla company.

Backing him up wa John Leland 'Lee'

Atwood, who became vice-presid nt

and chief of engineering for NAA; ~ -

tively he was Kindelberger's right-hand

man and also played the role of assist-

ant general manager. Kindelberger sub-

sequently assembled a talented team

of designers and engine r for the new

company, of whom the mo t important

would prove to be German-born Edgar

chmued, later to have su h a major influ-

ence on the design of the Mustang.

North American Aviation

Grows in Strength

ot only did AA have a number of key

new personnel and a smart new produc-

tion centre, but the NA-16 that gained

orders ub equ nt to the U AAC trainer

competition was a real winner. With

variou modifications and refinements the

basic layout spawned a series of developed

models that went on to meet a number

of USAAC needs. Eventually the type

easily outsold the Seversky BT-8 which

had in e s nce been officially preferred in

the original U AA ba ic trainer com-

petition. In addition, U avy (U )

intere t in the A-16' capabilities and

potential was a reason for the mating

of Pratt & Whitney's excellent R-1340

Wasp radial engine to the basic design,

although the original NA-16 design layout

envisaged the installation of this engine

in addition to the Wright R-975. The

ingredi nt were then in place to produce

the superb and long-running AT-6/

J T xan series of trainer that proved

invaluable and served 0 widely with

forces during World War Two. However,

despite these domestic successes, AA

knew that, in addition to sales within

the USA, the company needed to sell

its products abroad. With the required

export licences in place, the basic A-16

layout that d veloped into the AT-6/SNJ

T xan serie was eventually sold in a large

variety of gui es and configurations to a

great many for ign buyers.

Significant among these were Britain

and various British ommonwealth

countries. Thus the A-16 series became

highly significant in the story of the

Mustang, helping to e tablish impor-

tant connections between Britain and

CREATING A LEGE D

NAA. One of the first acquisitions of

US-manufactured aircraft by British pur-

chasing representatives during the later

1930s was a significant order for A-16-

series aircraft to help Britain's expanding

pilot training programme. This was some

time before th outbreak of the Second

World War, and again showed that some

personnel in Britain's military establish-

ment were considerably more far-sighted

and realistic than many Briti h politi-

cians of the day, in realizing the need for

rearmament with modern equipment. In

the early month of 19 Britain signed

for 200 A-49s, the first of ubstantial

numbers of A-16-derived two-seat train-

ers given the name Harvard in British and

British ommonwealth service. Officially

these 200 initial Harvards, followed by

200 more, had the AA charge number

A-49, but the lAA de ignation for

them was NA-16-1E. The first aircraft,

Harvard Mk I erial number 7000, was

pa sed to the Aeroplane & Armament

Experim ntal Establishment (A&AEE)

at MartIe ham Heath in uffolk, England,

in late 193 . It was the very first of several

thousand Harvards for British and British

Commonwealth operation that included

production by NAA as well as licence

manufacture in Canada, by oorduyn

Aviation Ltd, of 2,557 Mk Ilbs, the most

numerou ingle mark of the breed. These

aircraft became a vital part of Britain's

pilot training system in World War Two,

but equally significantly the Harvard wa

the start of the highly important rela-

tionship between Britain and NAA that

eventually fostered the co-operation out

of which the Mustang was derived.

Another of the many foreign buyers

of the NA-16 was Au tralia, which built

the developed A-33 (NAA designa-

tion A-16-2K) derivative of the A-16

line as the Wirraway light-combat and

training aircraft. Constructed by the

Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation

(CAC) in Australia from 1939 onward,

the Wirraway gave important service

during the Second World War in the

Pacific area, and was one of the first of the

NA-16line to ee actual front-I ine service.

Later, CA wa to becom an important

part of the Mustang story, and again the

A-16 had forged the link between this

Australian organization and AA that

would become significant in later year in

the Mu tang tory.

The process that led to the creation

of the Mustang was, to say the least,

17

unconventional. Perhaps it was in some

way appropriate that a de ign that was

destined to become such an xceptional

combat aircraft should come about in

an extraordinary way. Indeed, had it not

been for Britain's burgeoning need for

fighter aircraft, and the close connections

that had grown between NA and British

representatives in the USA, the Mustang

might never have been created. The tory

really tarted when Britain began to earch

for modern fighter aircraft to buy 'off the

helP in the U A. This search wa not as

easy as it has been made out to be in many

published sources. Although the A

was undoubtedly a potential major source

offighter aircraft (known as 'pursuit' types

in the SA at that time), unfortunately

fighter and fighter engine de ign had

considerably lagged behind in the U A

during the 19 0 . There were a number of

specific rea on for this. An important one

wa the increasingly entrenched attitude

among many senior SAA officers that

fast, well-defended bombers would always

get to their targets, obvia ing the need for

anything but the smallest possible fighter

force. This mind-set became so well estab-

lished that officers who advocated to the

contrary were often sidelined or retired

from the ervice so that their views would

not upset the developing tatu quo of the

bomber's invincibility.

Money, or a lack of it, wa a further ig-

nificant factor in the A falling behind

in the procurement of what we would

nowadays call 'state-of-the-art' designs.

The USAAC was just that, a component

of the US Army, and often encountered

considerable difficulty in obra ining money

for the development and purchase of new

designs, particularly if tho e types were

fighters. The Army was more interested

in the Air orps operating cia e-support

types that would work closely with ground

forces, rather than high-flying fighters. It

was not until a very commanding person-

ality took over as the head of the U AAC

that this situation started to change. This

was Henry H. 'Hap' Arnold, who e tower-

ing influence was to 'play such an impor-

tant role in the build-up of th U AA ,

it development into the AAF in

1941, and its central role in the air war

during the econd World War. Arnold

took over as the chief of the U AAC in

eptember J93 , but even at that point

it was still a truggle to obtain funds, par-

ticularly because the annual S defence

budget wa even then influenced by the

shortage of the economic crisi earlier in

the decade.

High-performance engine design work

had also slowed in the A during the

early 1930s in several key area. Thi

wa most noticeable in the development

of inline engine, particularly for high-

performance fighters. There were several

reasons for this unfortunate ituation,

including deficiencies in planning, lack

of money, and misplaced research and

development work, but a further reason

wa the general unwillingne s within

the U AAC to place much emphasis

on fighter de ign and evolution. This

was particularly unfortunate, for in the

1920s the USA had enjoyed a marked

advantage over many other countries,

with several promising inline engine

designs. However, this po ition wa lost

during the 1930s, and a number of other

countries, including Britain, Germany

and, to a lesser extent, France and the

oviet Union, began to develop capable

inline engines that had particular appli-

cation to high-performance fighters. The

U A lagged behind in this area, which

was all the more sur;xising when one

remembers that, in contrast, American

radial-engine development during that

period wa undoubtedly highly impor-

tant, and in turbosupercharging (exhau t-

augmented upercharging) for aero

engine the Americans literally led the

world. Ironically, some attempts had been

made during the early 1930s to create a

'modern' high-performance inline engine

in the USA, and several manufacturers

had either proposed or actually built a

number of designs. However, for a variety

of reasons, including changing official

requirements and a lack of development

money caused by the difficult economic

conditions of the time, only on of th se

actually reached production status. This

was the Allison V-1710, ubsequently

to playa significant part in the Mustang

story. Theoretically a 1,000hp-plus

engine with (non-turbo) supercharging,

the V-171 0 essentially began as a private-

venture programme. It received official

backing from the SAA from the mid-

1930s onwards, and in developed form it

was to power a wide variety of U AAC

and later U AAF fighter type. Indeed,

it was the only available inline engine of

any note in the U A in the late 1930s,

when fighter design in that country was

at last starting to gath r pace. This was

unfortunate in the long run as th V-1710

CREATING A LEGEND

had a variety of development problem,

and although available with supercharg-

ing it was eventually in tailed in several

fighter types without the benefit of turbo-

supercharging. A ignificant result wa

that aircraft thu powere I were compara-

tively poor performers at higher altitudes,

a factor that was again to have a major

part to play in the Mustang' tory.

Among the aircraft types that used the

Allison V-1710was the Curtiss P-40. This

purposeful-looking but rather sluggish

performer wa one of the main fighter pro-

grammes in the USA as the 1930s ended,

and the P-40 in several specific marks

and configurations was to play an impor-

tant role in the econd World War for a

number of Allied air forces. It was devel-

oped by the Curtiss Aeroplane Division of

the Curtis -Wright orporation, a famou

and long- tanding aircraft designer and

manufacturer that could trace its root,

through the ignificant personality of

Glenn Curtiss, right back to the earlie t

day of aviation in the A. In reality,

however, Curtiss was lagging behind in

all-metal monoplane fighter de ign as

the 1930 wore on. The company's chief

designer, Donovan Berlin, and hi design

team were umloubt Jly talented in their

particular field, but in reality the P-40'

layout was not particularly aerodynami-

cally refined or advanc d. The basic air-

frame of the PAO series dated back to that

of the famou urti s Model 75 series from

which it was derived. The original Model

75 had flown in May 1935, and the variou

subsequent production fighter series (most

members of which were referred to as

Hawk) were powered by a radial engine,

either the Pratt & Whim yR-1830Twin

Wasp or the Wright R-1820 yclone. The

type had been ordered by the USAAC as

the P-36, having placed well alongside

what became the eversky P-35 in a com-

petition that gave the orp its fir t really

modern fighter designs. Importantly for

Curtiss the Model 75 also proved to be an

export succe ,and the type was subject to

a particularly significant export order from

France. The fir t of everal French con-

tracts was signed in pring 193 ,and wa

intended to augment French production

of indigenou fighter type, many of which

were either increasingly obsolete or were

delayed in design and production. Curtis

had, however, seen the growth potential

in the P-36 airframe, and via a rather tor-

tuous route married the Allison V-1710

inline engine to the Model 75 airframe to

18

create what b m th P-40 family. On

the route t th r tion of the P-40 series

wa th urti YP- 7, the fir t of the

Alli on-engined urti fighter designs to

be built and flown. Fitted with a turbo-

upercharger, the -1710-engined YP-37

promi ed a con iderabl improvement

in p rformance over the radial-engined

Model 75 eries, but in r ality the XP-37

prototype and the YP-37 ervice test

example that followed it were not good

performers. The markedly aft position of

the cockpit in these aircraft wa , in any

case, largely unsuitable for a military air-

craft, and they uffered ignificantly from

engine and turbo upercharger probl ms.

How v r, the typ , main contribution to

Ameri an fighter d sign during that era

lay in its beautifully streamlined nose and

fuselage contours, which were reputed to

contribute significantly towards a 20 per

cent decrease in drag compared with the

radial-engined P-36. Further development

work by urtiss led to the famed and very

widely produced P-40 family of fighters.

The prototype XP-40 fir t flew on 14

October 193 , and this updated de ign,

known to Curti s as the Model 1, at once

generated considerable domestic and over-

ea intere t. The Curti approach to the

new aircraft, however, wa rather con rv-

ative, and drew on 0 many a p ct of the

P-36 d ign that the re ulting 'new' P-40

was a rather dated concept by the tim the

fir t production aircraft were delivered.

Power was provided by a supercharged

Alii on V-1710, but in the event no pro-

duction P-40s were fitted with the turbo-

supercharged V-1710. An initial purchase

came from the USAAC, which ordered a

batch of 524 Model 81 erie variants as

the P-40- U, P-40B-CU and P-40 -

Thi was, for its time, a substantial order

(it was the largest single military aviation

order in the A since the First World

War), and the new type performed well in

a competitive evaluation between several

new fighter designs that took place at

Wright Field, Ohio, in the late spring of

1939 and also included such types as the

new Bell P-39 Airacobra. The Model 1

also attracted French intere t and ord r .

ignificantly for the birth of what became

the Mustang, the new P-40 additionally

created interest among British purcha ing

representatives. At that time, however,

Britain did not place the substantial orders

that some published sources have claimed.

Instead, it was recognized that, due to the

large AAC and French orders for the

Mod I 1, the existing Curti produc-

tion facilities would be overstretched for

some time to come. Representations were

therefore (eventually) made to Britain'

friend, AA, to see if that company could

augment Curtiss production of the Model

I/PAO by manufacturing it under Ii ence

it elf for Britain. This idea was certainly

supported by some in the government

and U AAC. Interestingly, the AA

appear to have had a 'preferred list' of

aircraft companies that it felt should be

allowed to develop fighter designs. This

Ii t included Curtiss but did not includ

NAA, th U AAC apparently rea on-

ing that NAA was a comparatively new

company with no experience in fighter

design and was therefore unsuitable for

instituting its own de ign studies; but

could n vertheles become a licensed

producer of the combat aircraft of other

companies.

Britain Turns to North

American Aviation

uch a ituation must have been a con-

siderable source of fru tration to AA,

which wa certainly a comparatively new

company but at the same time had the

capability to introduce new ideas and

new approaches to the field of fighter

design and technology, and in the event

was certainly willing to do so. The exact

date that British representatives made

their initial representations to AA

about licence production of the P-40

is not clear. Certainly documents held

by Britain's ational Archives at Kew

do not uggest a precise date, but it wa

ome time in th autumn of 1939. At that

point the idea was not carried any further,

but world event were already dictat-