Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bjo 12093

Uploaded by

Cristina SecosanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bjo 12093

Uploaded by

Cristina SecosanCopyright:

Available Formats

DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.12093 www.bjog.

org

Correspondence

Fatally awed?

Sir, My rst quick glance at Fatally awed? A review and ethical analysis of lethal congenital malformations (BJOG 2012;119:13021308) suggested that the two tables provide valuable information for women who have to decide whether to have a late termination or to continue the pregnancy and allow the neonate to die naturally. But when I reached the associated commentary in which Chervenak and McCullough congratulate the authors for asserting their professional responsibility to offer or recommend nonaggressive management, I realised that the authors presumed that abortion would not be ethical and that such pregnancies should continue: their concern is for the appropriate management of the affected infants. I hold the view that Chervenak and McCullough condemn as fallacious rights-based reductionism in obstetric ethics.1 In contrast to them, I regard the woman as having autonomy over her fetus up to the time when she decides to confer status on it as a person by giving birth. This is recognised in British law: the Abortion Act 1967 was amended in 1990 to allowed abortion at any gestation if there is a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped and, in 1998, the Court of Appeal conrmed a lower court ruling that a woman has a right to refuse caesarean section when this is recommended to protect either herself or her fetus from serious harm.2 Since 1990, in England and Wales, fetal abnormality has been the reason for relatively few terminations, with little change from year to year: in 2008, there were 1864 terminations performed up to 24 weeks of gestation and 124 later in pregnancy.3 Chervenak and McCullough believe that when a woman accepts obstetric care the viable fetus acquires independent status as a patient, so that, on rare occasions, it would be proper to coerce the woman into receiving treatment for which she has refused voluntary consent. The article in the current issue of BJOG is relevant in Britain only when the malformation is discovered for the rst time at delivery or

when the woman, aware of the malformation, has refused termination. &

References

1 Chervenak FA, McCullough lB, Brent RL. The professional responsibility model of obstetrical ethics: avoiding the perils of clashing rights. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:315.e15. 2 St. Georges Healthcare N.H.S. Trust v S [1998] 3 W.L.R. 936, 1998, Court of Appeal. 3 Abortion Statisics 2008. Dept of Health, 2009. [www.dh.gov.uk/en/ Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_099285]. Accessed 9 November 2012.

D Paintin

Emeritus Reader in Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Imperial College, London, UK

Accepted 4 October 2012.

DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.12093

Fatally awed?

Authors Reply Sir, We thank Dr Paintin for his interest in our article.1,2 Paintins main concerns appear to relate to the views of Chervenak and McCullough in their accompanying commentary on the professional responsibility of obstetricians.3 Both responses appear to miss the central point that we argued: in counselling, language can corrupt both the inner logic of the clinicians decision-making process and the counselling of families facing difcult decisions. Paintin is wrong in characterising our argument as only relevant in the event of fetal abnormality undiagnosed at birth or when a decision has been made to continue the pregnancy. Our argument concerns the need for clarity in the language used in counselling. This applies whether the woman decides to terminate or continue the pregnancy and, if continuing, on what terms and with what goals.

2013 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2013 RCOG

371

You might also like

- Medical Errors and Adverse Events: Managing the Aftermath: Managing the AftermathFrom EverandMedical Errors and Adverse Events: Managing the Aftermath: Managing the AftermathNo ratings yet

- Pro Life Campaign UN Submission: Valuing Mother & BabyDocument8 pagesPro Life Campaign UN Submission: Valuing Mother & BabyPro Life CampaignNo ratings yet

- OB GYN EmergenciesDocument266 pagesOB GYN EmergenciesTemesgen EndalewNo ratings yet

- Uksc 2013 0136 Judgment PDFDocument38 pagesUksc 2013 0136 Judgment PDFmuhumuzaNo ratings yet

- Prenatal Management of AnencephalyDocument5 pagesPrenatal Management of AnencephalyarifsandroNo ratings yet

- F8 Reading-Birth To Death Symposium-Home BirthDocument5 pagesF8 Reading-Birth To Death Symposium-Home Birthemkay1234No ratings yet

- EuthanasiaDocument4 pagesEuthanasiaKumar G PalaniNo ratings yet

- 64 FullDocument4 pages64 FullFuraya FuisaNo ratings yet

- Ethical Challenges in The New World of Maternal - Fetal SurgeryDocument7 pagesEthical Challenges in The New World of Maternal - Fetal SurgeryÊndel AlvesNo ratings yet

- Montgomery V Lanarkshire Health Board (2015)Document23 pagesMontgomery V Lanarkshire Health Board (2015)thomas15hunterNo ratings yet

- Acknowledged Dependence and The Virtues of Perinatal Hospice. Philosophy 2016Document16 pagesAcknowledged Dependence and The Virtues of Perinatal Hospice. Philosophy 2016Andrés F. UribeNo ratings yet

- Autopsy in The Event of Maternal Death - A UK Perspective: ReviewDocument8 pagesAutopsy in The Event of Maternal Death - A UK Perspective: ReviewMayada OsmanNo ratings yet

- Futility and The Obligations of Physicians: Bradley E. WilsonDocument13 pagesFutility and The Obligations of Physicians: Bradley E. WilsondocsincloudNo ratings yet

- After Birth AbortionDocument6 pagesAfter Birth AbortionRaymond GibsonNo ratings yet

- Tog 12690Document9 pagesTog 12690saeed hasan saeedNo ratings yet

- Ethic Dan Legal IssueDocument4 pagesEthic Dan Legal IssueIDYATUL HASANAHNo ratings yet

- Sociology Health Illness - 2021 - Middlemiss - Too Big Too Young Too Risky How Diagnosis of The Foetal Body DeterminesDocument18 pagesSociology Health Illness - 2021 - Middlemiss - Too Big Too Young Too Risky How Diagnosis of The Foetal Body DeterminesVynna SinoNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Nursing ClinicsDocument133 pagesCritical Care Nursing ClinicsJune DumdumayaNo ratings yet

- SBL-HRA Debate Cup 2016 - Legal Abortion Not a Human RightDocument13 pagesSBL-HRA Debate Cup 2016 - Legal Abortion Not a Human RightJirehPorciunculaNo ratings yet

- Right to Safe Abortion as a Human RightDocument15 pagesRight to Safe Abortion as a Human RightJirehPorciuncula0% (1)

- After-Birth Abortion: Why Should The Baby Live?Document6 pagesAfter-Birth Abortion: Why Should The Baby Live?_zero_cool_No ratings yet

- The Legal Status of Frozen EmbryosDocument35 pagesThe Legal Status of Frozen EmbryosEskit Godalle NosidalNo ratings yet

- J Med Ethics 2012 Giubilini Medethics 2011 100411Document6 pagesJ Med Ethics 2012 Giubilini Medethics 2011 100411marhussardNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument13 pagesBlood TransfusionIshika ChauhanNo ratings yet

- The Groningen Protocol: Concerns Over Infant EuthanasiaDocument2 pagesThe Groningen Protocol: Concerns Over Infant EuthanasiaDaniel BlancoNo ratings yet

- Decision Making in The Neonatal Intensive Care Environment: R PA RiversDocument8 pagesDecision Making in The Neonatal Intensive Care Environment: R PA RiversmohammedNo ratings yet

- Between Dr Allen and Dr MillerDocument31 pagesBetween Dr Allen and Dr MillerMinura AdikaramNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Delivery: An Argument Against Requiring Consent: Rodney W. PetersenDocument3 pagesVaginal Delivery: An Argument Against Requiring Consent: Rodney W. PetersenAinun Jariah FahayNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Euthanasia: A Claim For An Immoral Law: Serge Vanden Eijnden and Dana MartinoviciDocument10 pagesNeonatal Euthanasia: A Claim For An Immoral Law: Serge Vanden Eijnden and Dana Martinovicimchs_libNo ratings yet

- English Week 11Document4 pagesEnglish Week 11api-336093393No ratings yet

- Coffey - Et - Al-2016-Advance Directives in Five CountriesDocument11 pagesCoffey - Et - Al-2016-Advance Directives in Five Countriesrizki ikhsanNo ratings yet

- PreeclampsiaDocument58 pagesPreeclampsiarhyanne100% (8)

- Bioethics Dilemma of Conjoined Twins CareDocument2 pagesBioethics Dilemma of Conjoined Twins CareSulistyawati WrimunNo ratings yet

- Duty of Candour: The Obstetrics and Gynaecology Perspective: CommentaryDocument4 pagesDuty of Candour: The Obstetrics and Gynaecology Perspective: CommentaryKeeranmayeeishraNo ratings yet

- Conscientious Objection To Abortion, How To Strike A Legal and Ethical Balance Between Conflicting Rights?Document7 pagesConscientious Objection To Abortion, How To Strike A Legal and Ethical Balance Between Conflicting Rights?Mario AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- What's Wrong With in Vitro Fertilization?: by Natalie Hudson, Executive Director ofDocument5 pagesWhat's Wrong With in Vitro Fertilization?: by Natalie Hudson, Executive Director ofcambfernandezNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Autonomy and Informed Consent: Ethic Theory Moral Prac (2016) 19:225 - 244 DOI 10.1007/s10677-015-9610-8Document20 pagesObstetric Autonomy and Informed Consent: Ethic Theory Moral Prac (2016) 19:225 - 244 DOI 10.1007/s10677-015-9610-8Sindy Amalia FNo ratings yet

- Abortion and Womens Health - April 2017Document28 pagesAbortion and Womens Health - April 2017Gabriel SantosNo ratings yet

- Controversies in Perinatal Medicine The Fetus As A Patient 28 Ethics On The Frontier of Fetal ResearchDocument9 pagesControversies in Perinatal Medicine The Fetus As A Patient 28 Ethics On The Frontier of Fetal ResearchZiel C EinsNo ratings yet

- A Defence of Voluntary Sterilisation: Paddy McqueenDocument19 pagesA Defence of Voluntary Sterilisation: Paddy McqueenyogurtNo ratings yet

- What They Didnt Tell You About CPR and PEG Feeds PresentationDocument32 pagesWhat They Didnt Tell You About CPR and PEG Feeds PresentationabcdcattigerNo ratings yet

- Patient Care Demonstrated Through Tragic Medical Error CaseDocument14 pagesPatient Care Demonstrated Through Tragic Medical Error CaseRobyn KentNo ratings yet

- Hum. Reprod.-2005-Farquharson-3008-11Document4 pagesHum. Reprod.-2005-Farquharson-3008-11venkayammaNo ratings yet

- Core Clinical Cases in Og Signed 3 PDFDocument183 pagesCore Clinical Cases in Og Signed 3 PDFErine Della AprlaNo ratings yet

- After-Birth Abortion: Why Should The Baby Live?Document6 pagesAfter-Birth Abortion: Why Should The Baby Live?viperexNo ratings yet

- Drug Development in UK Lancet 2007Document2 pagesDrug Development in UK Lancet 2007Lancre witchNo ratings yet

- PHD Research PROPOSAL Arulampalam PDFDocument5 pagesPHD Research PROPOSAL Arulampalam PDFKHMHNNo ratings yet

- Magna YeDocument3 pagesMagna YeDiane Ronalene Cullado MagnayeNo ratings yet

- Francesca Minerva. After-Birth AbortionDocument3 pagesFrancesca Minerva. After-Birth AbortionArt VandelayNo ratings yet

- Screenshot 2023-04-03 at 4.35.41 PMDocument183 pagesScreenshot 2023-04-03 at 4.35.41 PMderilNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations of Fetal TherapyDocument13 pagesEthical Considerations of Fetal TherapyRyan SadonoNo ratings yet

- Involvement of Nurses in EuthanasiaDocument6 pagesInvolvement of Nurses in EuthanasiaEvan SmixNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Pro AbortionDocument7 pagesThesis On Pro Abortioncynthiawilsonarlington100% (2)

- Ethics Refusal of TreatmentDocument8 pagesEthics Refusal of TreatmentPeta BeckhamNo ratings yet

- AbortionDocument5 pagesAbortionYlenol HolmesNo ratings yet

- Human Life and Bio Medical Issues: AbortionDocument11 pagesHuman Life and Bio Medical Issues: AbortionJoliane CalderaNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Neurology 4th Ed - G. Fenichel (Churchill Livingstone, 2007) WW PDFDocument232 pagesNeonatal Neurology 4th Ed - G. Fenichel (Churchill Livingstone, 2007) WW PDFCampan AlinaNo ratings yet

- Groningen ProtocolDocument5 pagesGroningen Protocolakiva10bNo ratings yet

- The Placenta and Neurodisability 2nd EditionFrom EverandThe Placenta and Neurodisability 2nd EditionIan CrockerNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Treatment of Ovarian Vein SyndromeDocument13 pagesLaparoscopic Treatment of Ovarian Vein SyndromeCristina SecosanNo ratings yet

- Byung Kang Pelvis 09.15.2014Document121 pagesByung Kang Pelvis 09.15.2014Elena ConstantinNo ratings yet

- Bjo 12087Document8 pagesBjo 12087Cristina SecosanNo ratings yet

- Bjo 12064Document2 pagesBjo 12064Cristina SecosanNo ratings yet

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease PDFDocument13 pagesGestational Trophoblastic Disease PDFCristina SecosanNo ratings yet

- Bjo 12062Document11 pagesBjo 12062Cristina SecosanNo ratings yet

- Smoking Cessation in Pregnant Women With Mental Disorders: A Cohort and Nested Qualitative StudyDocument9 pagesSmoking Cessation in Pregnant Women With Mental Disorders: A Cohort and Nested Qualitative StudyCristina SecosanNo ratings yet

- Bjo 12052Document11 pagesBjo 12052Cristina SecosanNo ratings yet

- Rare TumorsDocument184 pagesRare TumorsdherangesheetalNo ratings yet

- Sim Ul Are Rezident I at 2011Document26 pagesSim Ul Are Rezident I at 2011Cristina SecosanNo ratings yet

- Management of Pregnancy Related BleedingDocument75 pagesManagement of Pregnancy Related BleedingChuah Wei Hong100% (1)

- Role of Physiotherapy in Antenatal and Post-Natal Care: Dr. Venus Pagare (PT)Document96 pagesRole of Physiotherapy in Antenatal and Post-Natal Care: Dr. Venus Pagare (PT)Haneen Jehad Um MalekNo ratings yet

- Update On Medical Disorders in Pregnancy An Issue of Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics The Clinics Internal MedicineDocument217 pagesUpdate On Medical Disorders in Pregnancy An Issue of Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics The Clinics Internal Medicinemeriatmaja100% (1)

- H-Mole Pathophysiology in Schematic DiagramDocument1 pageH-Mole Pathophysiology in Schematic DiagramFaith Lumayog100% (2)

- (Get Through) Chu, Justin - Clark, T. Justin - Coomarasamy, Arri - Smith, Paul Philip - Get Through MRCOG Part 3 - Clinical Assessment (2019, CRC Press) PDFDocument217 pages(Get Through) Chu, Justin - Clark, T. Justin - Coomarasamy, Arri - Smith, Paul Philip - Get Through MRCOG Part 3 - Clinical Assessment (2019, CRC Press) PDFwai lynn100% (1)

- NCM 109 Course OutlineDocument2 pagesNCM 109 Course OutlineJoseph Joshua OtazaNo ratings yet

- Breech Presentation and Its Management2Document17 pagesBreech Presentation and Its Management2maezu100% (3)

- 51 EpisiotomyDocument21 pages51 Episiotomydr_asaleh100% (2)

- Management Placenta Percreta Succesfully With Total Abdominal Hysterectomy A Case ReviewDocument12 pagesManagement Placenta Percreta Succesfully With Total Abdominal Hysterectomy A Case ReviewHI DayatNo ratings yet

- How To Read A CTGDocument16 pagesHow To Read A CTGHussain H. HussainNo ratings yet

- Fellows ObstetricsDocument13 pagesFellows ObstetricsAnonymous 9QxPDpNo ratings yet

- Fetal MalpresentationDocument83 pagesFetal MalpresentationArianJubaneNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Labor.Document2 pagesFactors Affecting Labor.Salman KhanNo ratings yet

- NCLXDocument5 pagesNCLXkhadeejakhurshidNo ratings yet

- Premature Rupture of MembraneDocument17 pagesPremature Rupture of MembraneShimaa Abdel hameedNo ratings yet

- Historical Perspective in Maternity NursingDocument3 pagesHistorical Perspective in Maternity NursingDelphy Varghese75% (4)

- English For MidwiferyDocument27 pagesEnglish For MidwiferyRetno AW100% (1)

- Northern Mindanao Medical Center Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Schedule For November 2019Document8 pagesNorthern Mindanao Medical Center Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Schedule For November 2019Janellah BatuaanNo ratings yet

- Malpresentation and Malposition - ShoulderDocument5 pagesMalpresentation and Malposition - ShoulderNishaThakuri100% (1)

- L Mollart Pregnancy Oedema, Emotions and ReflexologyDocument7 pagesL Mollart Pregnancy Oedema, Emotions and ReflexologyMoh. Fahmi FathullahNo ratings yet

- FP561 Suryakanta JayasinghDocument3 pagesFP561 Suryakanta Jayasinghsuryakanta jayasinghNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Labor Progress with the PartographDocument6 pagesMonitoring Labor Progress with the Partographalyssa marie salcedo100% (1)

- Ultrasound of The Pregnant Acute AbdomenDocument16 pagesUltrasound of The Pregnant Acute Abdomenjohn omariaNo ratings yet

- Obstetrics and Gynecology ClinicsDocument201 pagesObstetrics and Gynecology ClinicsaedicofidiaNo ratings yet

- Case Presewntation - C - SectionDocument12 pagesCase Presewntation - C - Sectionpriyanka50% (2)

- Daftar Pustaka ObgynDocument1 pageDaftar Pustaka ObgynISMJNo ratings yet

- PMNP 2023 Paloyon ProperDocument6,574 pagesPMNP 2023 Paloyon ProperJeckay P. OidaNo ratings yet

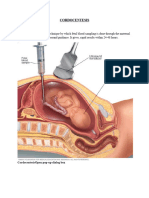

- CORDOCENTESISDocument6 pagesCORDOCENTESISSagar HanamasagarNo ratings yet

- What Is Noninvasive Prenatal Screening (NIPS) ?Document5 pagesWhat Is Noninvasive Prenatal Screening (NIPS) ?Le Phuong LyNo ratings yet

- Cervical Insufficiency Diagnosis and ManagementDocument8 pagesCervical Insufficiency Diagnosis and ManagementkukadiyaNo ratings yet