Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Duns Scotus On The Will and Morality

Uploaded by

Hector Fabian GarciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Duns Scotus On The Will and Morality

Uploaded by

Hector Fabian GarciaCopyright:

Available Formats

Duns Scotus on the Will and Morality

Kent, Bonnie Dorrick, 1953Journal of the History of Philosophy, Volume 27, Number 2, April 1989, pp. 303-305 (Review)

Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press

For additional information about this article

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/hph/summary/v027/27.2kent02.html

Access Provided by Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana at 02/28/11 8:39PM GMT

BOOK REVIEWS

303

sua estensione. Altrove (198) sembra suggerire che il significato di un termine equivalga a un "contenuto mentale"; mentre a p. 164 tira in ballo la"predicazione di un significato individuale"(?) che sarebbe possibile soltanto "nei confronti delrindividuo stesso." Nei capitoli concernenti i sillogismi (2o7-5o), D'Onofrio si dilunga nell'esposizione di una materia logica povera, mentre sorvola su argomenti che sarebbe stato opportuno sviluppare. Accenna frettolosamente al fatto che per Apuleio la prima premessa in un sillogismo/~ quella contenente il soggetto della conclusione (a24) e nota che cib comporta un'inversione nell'ordine tradizionale delle premesse 027); ma non cerca di approfondire le ragioni della scelta di Apuleio. Liquida la questione delle proposizioni singolari che tanto interesse susciter~ nei logici medievali, affermando, tra l'altro, chela verit~ delle proposizioni singolari "dipender~ sempre e soltanto"(??) dalla verit~ delle universali corrispondenti (~ lo): come se una proposizione singolare non potesse esser vera e la corrispondente universale falsa. Infine, pur facendo continuo riferimento ai Topici di Aristotele, non si sofferma mai a illustrare in modo organico---a beneficio del lettore---la natura di un locus aristotelico, come cio~ quest'ultimo si componesse di una prescrizione e di una giustificazione e come le pi/l recenti interpretazioni siano divise nel considerare il locus propriamente detto ora la prescrizione ora la giustificazione (si confronti su questo punto e, in generale, sulla tradizione dei loci nel medioevo il ben piO agguerrito lavoro di N.J. Green-Pedersen, The Tradition of the Topics in the Middle Ages, M0nchen-Wien: Philosophia Verlag, 1984). Come ho gi~ osservato, comunque, questi rilievi non intaccano l'utilit~ del lavoro di D'Onofrio: ne limitano tuttavia la portata e sono un'ulteriore riprova del fatto che, per affrontare argomenti attinenti alia logica antica e medievale, le consuete competenze storico-filologiche non sono sufficienti. MASSIMO MUGNAI Universit~ di Firenze

Duns Scotus on the Will and Morality. Selected and Translated with an Introduction by Allan B. Wolter, O.F.M. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1986. Pp. x + 543. $54-95.

Long before C. S. Peirce ranked him among "the profoundest metaphysicians" of all time, Duns Scotus was known mainly for his work in metaphysics. Allan B. Wolter is known mainly for his interpretations of Scotus' metaphysics---feats of clarification which must place Wolter among the most lucid expositors of all time. Scotus' teachings on the will have attracted less attention than his metaphysics, and even less is known about Scotus' ethics. Did the Subtle Doctor ever address an ethical question? Were it not for his well-known claim that "everything other than God is good because it is willed by God and not vice versa," one might doubt whether he did. The impression that Scotus was most interested in speculative problems is accurate. Among those were various problems raised by his conception of the will. The freedom of the will, however, is not just one more theoretical knot to be untied in the interests of a consistent metaphysics. To Scotus it is a necessary condition for moral responsibility.

304

JOURNAL

OF T H E H I S T O R Y

OF P H I L O S O P H Y

27:2 APRIL 1 9 8 9

Without a coherent account o f the will's freedom, no true ethics is possible. T h u s the metaphysical analysis o f the will becomes the foundation o f Scotus' ethical theory, and it is the ethical theory we need to gain a fuller appreciation o f his philosophy. Wolter's book g o e s a long way toward meeting that need. This massive tome could easily have been two books. It includes excerpts from Scotus' writings and Wolter's translations o f them, as well as a general introduction and notes on the selections which could stand alone as an overview o f Scotus' psychology and ethics. O f the thirty-four selections, one is from Scotus' Quodlibet, one from his Lectura, one from his questions on Aristotle's Metaphysics. T h e rest are taken mainly from the Ordinatio (Scotus' revised version o f his c o m m e n t a r y on the Sentences). T h e critical edition o f Scotus' works is appearing with agonizing slowness. Since most o f the material relevant to ethics is found in Books I I I and IV o f his commentary on the Sentences, some years will pass before scholars can look to the Vatican edition for texts. Heretofore anyone interested in Scotus' ethics has been at the mercy of the W a d d i n g edition, and because very few o f the texts were available in translation, the Latinless have had to d e p e n d almost exclusively on secondary literature. Wolter's book helps on both counts. He has used the better manuscripts to correct the W a d d i n g text and supplied a readable translation o f Scotus' perplexing Latin. Wolter's notes on the selections, which are g r o u p e d together at the beginning of the volume, r u n to almost a h u n d r e d pages. Here "note" should be taken in the broad sense. While each includes exposition of the related text, many place it in the wider context o f Scotus' thought and provide useful information about contemporary controversies. T h u s the notes are often more on the o r d e r o f brief lectures: philosophical issues are set out, historical background is presented, technical terminology is explained. With such a learned guide, even those unfamiliar with medieval philosophy could make their way t h r o u g h the selections. Wolter describes the p u r p o s e of the collection as twofold: first, to correct some common misconceptions about Scotus' ethics; second, to show the unity o f his ethical system. T h e principal misconception is that if things are good because God wills them, moral truth is not accessible to natural reason. Wolter argues convincingly that the consequent does not follow when the antecedent is properly interpreted. T h e outlines o f this analysis were sketched in an earlier article. Here the case is presented in greater detail, along with s u p p o r t i n g texts that enable the r e a d e r to j u d g e for himself. Wolter has omitted Scotus' most technical discussions o f the will, chosen texts that are comparatively straightforward, and included just enough o f those to show the coherence o f the psychology and the ethical theory. Since so much has been made o f Scotus' claim that nothing other than the will is the total efficient cause o f volition, his change in position deserves a bit more attention than Woher gives it. (Scotus subsequently acknowledged the intellect as a partial but subordinate cause.) Anselm's doctrine o f the will's two affections looms large in the texts on the will. Scotus follows Anselm in describing the will's freedom as an affection for justice, but even as he borrows from Anselm's teachings, he radically alters them. For Anselm, the affection for justice was lost t h r o u g h Adam's sin and can only be regained through God's grace. For Scotus, the affection is rooted in the will's very nature. In effect, Anselm does not

BOOK REVIEWS

305

distinguish between moral and meritorious goodness. Scotus does. He refits for service in moral philosophy what originated as a theological doctrine. And, with that typically scholastic combination of deference and distortion, the vast difference between his own views and Anselm's passes almost without remark. The importance of the will is evident in the texts on ethical issues. Unlike Aquinas, who posited temperance and courage in the sense appetite, Scotus attributes all the moral virtues to the will. Since angels as well as human beings have wills, one might object that angels must be able to acquire moral virtues. Kantians will not be entirely disappointed by Scotus' reply. Virtues are generated from correct choices by the will. If an angel's intellect shows it what choices should be made by one subject to passions, then even though the angel itself does not have those passions, it will still be able to choose in accordance with the dictates of its intellect. If it does choose accordingly, moral virtue will be generated in the angel's will. Did Scotus himself believe that angels can acquire moral virtues? He does provide an elaborate argument in support of that position. But he then observes that some may find the position displeasing, and so explains how one might argue against it. Having answered his own answer to an objection, Scotus moves on--leaving the reader to wonder which position, if either, he accepted. The selections on ethics include not only the expected (virtues, God's power, moral goodness, and natural law) but also the unexpected (marriage, perjury, enslavement, and the obligation to keep secrets). If what is wanted is a comprehensive system of ethics, with every thread woven into the fabric of a theory and none left dangling, one is likely to find Scotus a disappointment. The Subtle Doctor is of a more analytical bent, more interested in exploring the issues and offering fresh insights than in ethical system-building. Had he lived to a ripe old age, perhaps he would have produced some vast, tightly woven theory. It is impossible to say. One can say, however, that what we have is both consistent and consistently thought provoking.

BONNIE KENT

The Catholic University of America

Amos Funkenstein. Theology and the Scientific Imagination from the Middle Ages to the Seventeenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986. Pp. xii + 4~1. $47.5 ~ 9 It is Funkenstein's thesis that "to many seventeenth-century thinkers, theology and science merged into one idiom, part of a veritable secular theology such as never existed before or after" (ix); among the thinkers he has in mind are Galileo, Descartes, Leibniz, Newton, Hobbes, and Vico (3)" The bulk of Funkenstein's book is devoted to "shed[ding] some light on the unique texture of this common idiom by comparing it to past theological interests or modes of reasoning" (346). As to the content of this secular theology, Funkenstein claims that the thinkers mentioned above "dealt with most classical theological issues---God, the Trinity, spirits, demons, salvation, the Eucharist" (3). If this means only that each of the above thinkers on occasion dealt with at least one of

You might also like

- Duns Scoto e L'analogia EntisDocument14 pagesDuns Scoto e L'analogia EntisMarisa La BarberaNo ratings yet

- Storia Del Concetto Di Persona PDFDocument31 pagesStoria Del Concetto Di Persona PDFAndre SegoviaNo ratings yet

- Eco, Analogia EntisDocument11 pagesEco, Analogia Entisbrevi1No ratings yet

- La Questione SardaDocument245 pagesLa Questione SardaFábio Carvalho100% (1)

- FUNCIÓN DE ENSEÑAR. - Cánones Preliminares (Cc. 747-755)Document58 pagesFUNCIÓN DE ENSEÑAR. - Cánones Preliminares (Cc. 747-755)Ebher JonathanNo ratings yet

- Stickler Celibato Ecclesiastico PDFDocument63 pagesStickler Celibato Ecclesiastico PDFgiovanniNo ratings yet

- Analisi del rapporto tra scienza e filosofia: in Schlick e VoltaireFrom EverandAnalisi del rapporto tra scienza e filosofia: in Schlick e VoltaireNo ratings yet

- Realismo Dialettico: il Materialismo Dialettico da Stalin a oggiFrom EverandRealismo Dialettico: il Materialismo Dialettico da Stalin a oggiNo ratings yet

- I Tordi Beffeggiatori Il Progetto Della Rivista Di Filosofia Scientifica (1881-1891) Attraverso Alcune Parole-ParadigmaDocument30 pagesI Tordi Beffeggiatori Il Progetto Della Rivista Di Filosofia Scientifica (1881-1891) Attraverso Alcune Parole-ParadigmaEdizioni AltravistaNo ratings yet

- La Soluzione Scettica Allo Scetticismo PDFDocument24 pagesLa Soluzione Scettica Allo Scetticismo PDFMonika SagoljNo ratings yet

- Il Mistero della Luce svelato - Saggio di una teoria completa e unitaria dei fenomeni luminosi in base alle ultime conoscenze sulla materia e sulla energiaFrom EverandIl Mistero della Luce svelato - Saggio di una teoria completa e unitaria dei fenomeni luminosi in base alle ultime conoscenze sulla materia e sulla energiaNo ratings yet

- A Duecento Anni Dalla Morte Di Kant - 2004Document16 pagesA Duecento Anni Dalla Morte Di Kant - 2004sankaratNo ratings yet

- Mente, Pensiero, Natura: Editoriali ed articoli sulla Rivista «Studium» (2000-2011)From EverandMente, Pensiero, Natura: Editoriali ed articoli sulla Rivista «Studium» (2000-2011)No ratings yet

- La ragione laicizzante dei filosofi: Il pensiero critico nel medioevoFrom EverandLa ragione laicizzante dei filosofi: Il pensiero critico nel medioevoNo ratings yet

- Campa Le Origini Magiche Della Scienza Uno Sguardo Alla Tradizione Filosofica 2019Document33 pagesCampa Le Origini Magiche Della Scienza Uno Sguardo Alla Tradizione Filosofica 2019Federico BoccaneraNo ratings yet

- Scienza Linguaggio Ed EticaDocument40 pagesScienza Linguaggio Ed EticaNora ArtsNo ratings yet

- Studi Sul Legame Della Posizione Politica Tra Cina e Occidente Nel 500Document11 pagesStudi Sul Legame Della Posizione Politica Tra Cina e Occidente Nel 500Wang ZhengNo ratings yet

- FILOSOFIA Del Card Paolo DezzaDocument118 pagesFILOSOFIA Del Card Paolo Dezzakkadilson100% (1)

- DiltheyDocument2 pagesDiltheyvitazzoNo ratings yet

- Ecosofia: Sapienze della terra per la coltivazione dell'umanitàFrom EverandEcosofia: Sapienze della terra per la coltivazione dell'umanitàNo ratings yet

- Il Tao Della Fisica - RecensioneDocument5 pagesIl Tao Della Fisica - RecensioneGiuseppe LiniNo ratings yet

- Ragione, Creatività, Fede: Saggi di scienze cognitive delle religioniFrom EverandRagione, Creatività, Fede: Saggi di scienze cognitive delle religioniNo ratings yet

- Miti scientifici e potere della logica. Scienza, evoluzione, conoscenza.From EverandMiti scientifici e potere della logica. Scienza, evoluzione, conoscenza.No ratings yet

- Aspetti Della Filosofia ModernaDocument18 pagesAspetti Della Filosofia ModernaAnonimoNo ratings yet

- Einstein e La Filosofia Dentro La ScienzaDocument26 pagesEinstein e La Filosofia Dentro La ScienzaVictor CantuárioNo ratings yet

- Studium- Psicologia e lavoro: Nuove prospettive per l’orientamento e la gestione delle competenze nello scenario attuale: Rivista bimestrale 2017 (4)From EverandStudium- Psicologia e lavoro: Nuove prospettive per l’orientamento e la gestione delle competenze nello scenario attuale: Rivista bimestrale 2017 (4)No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument158 pagesUntitledMatheusNo ratings yet

- Le vie della filosofia: Soria della filosofia occidentale ad uso delle scuole medie superiori e degli autodidattiFrom EverandLe vie della filosofia: Soria della filosofia occidentale ad uso delle scuole medie superiori e degli autodidattiNo ratings yet

- Popper Postumo Su Scienza e ReligioneDocument5 pagesPopper Postumo Su Scienza e ReligionemarcotrainitoNo ratings yet

- Einaudi 2002Document44 pagesEinaudi 2002ClaymindNo ratings yet

- Dorato, Mauro - Istituzioni Di Filosofia Della ScienzaDocument70 pagesDorato, Mauro - Istituzioni Di Filosofia Della ScienzaRenato Degli EspostiNo ratings yet

- Dibattito Sul MetodoDocument4 pagesDibattito Sul Metodolorenzen62No ratings yet

- Paolo Dezza FilosofiaDocument163 pagesPaolo Dezza FilosofiaAny AnyNo ratings yet

- Long Anthony A. La Filosofia Helenistica.Document454 pagesLong Anthony A. La Filosofia Helenistica.Felipe Stelzer100% (1)

- Duns ScotoDocument11 pagesDuns ScotoFedericaSchiavonNo ratings yet

- Umena Luca - Voltaire e La Fisica NewtonianaDocument5 pagesUmena Luca - Voltaire e La Fisica Newtonianamariobianchi182No ratings yet

- Aristotele Capitolo 1Document8 pagesAristotele Capitolo 1MatteoNo ratings yet

- Filosofia SviluppoDocument12 pagesFilosofia Sviluppogabriel magoNo ratings yet

- Moloch e i bambini del re. Il sacrificio dei figli nella BibbiaFrom EverandMoloch e i bambini del re. Il sacrificio dei figli nella BibbiaNo ratings yet

- David Konstan ITALIANODocument8 pagesDavid Konstan ITALIANOValeria RapisardaNo ratings yet

- Carlo A. Viano-La Logica Di Aristotele-Taylor (1955) PDFDocument316 pagesCarlo A. Viano-La Logica Di Aristotele-Taylor (1955) PDFjulianvidela100% (1)

- Riassunti Filosofia AristoteleDocument15 pagesRiassunti Filosofia AristoteleMarco Uras73% (11)

- Il valore della prova scientifica nel processo italiano e americanoFrom EverandIl valore della prova scientifica nel processo italiano e americanoNo ratings yet

- Oltre la conoscenza. Il pensiero metaformale di Guido CalogeroFrom EverandOltre la conoscenza. Il pensiero metaformale di Guido CalogeroNo ratings yet

- Riscontri. Rivista di cultura e di attualità: N. 3 (Settembre-Dicembre 2021)From EverandRiscontri. Rivista di cultura e di attualità: N. 3 (Settembre-Dicembre 2021)No ratings yet

- Cosa Fanno I Filosofi Oggi - BobbioDocument4 pagesCosa Fanno I Filosofi Oggi - BobbioSimona MerlinNo ratings yet

- StoriaDocument8 pagesStoriaricoNo ratings yet

- La Logica Di AristoteleDocument316 pagesLa Logica Di AristoteleMariana Falqueiro100% (2)

- Caporal EttiDocument27 pagesCaporal EttiemanueleNo ratings yet

- Glauco e ScillaDocument2 pagesGlauco e ScillaSusy GalloNo ratings yet

- Mini Guida Altezza Arretramento SellaDocument8 pagesMini Guida Altezza Arretramento SellacactusmtbNo ratings yet

- Boulez - Memoriale Analisi (Italian)Document8 pagesBoulez - Memoriale Analisi (Italian)sertimoneNo ratings yet

- Santa Brigida 1 AnnoDocument4 pagesSanta Brigida 1 AnnoangeloNo ratings yet

- La Pesca MiracolosaDocument2 pagesLa Pesca Miracolosaaceto_giacomoNo ratings yet

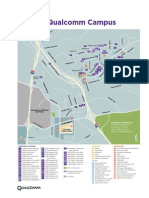

- Qualcomm San Diego MapDocument1 pageQualcomm San Diego Mapj0880jNo ratings yet