Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Defining Grief Play in Mmorpgs: Player and Developer Perceptions

Uploaded by

tramenesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Defining Grief Play in Mmorpgs: Player and Developer Perceptions

Uploaded by

tramenesCopyright:

Available Formats

Dening Grief Play in MMORPGs: Player and Developer Perceptions

Chek Yang Foo

Curtin University of Technology Higher Degree Research Unit, CBS GPO Box U1987 Perth WA 6845, Australia

Elina M.I. Koivisto

Nokia Research Center P.O. Box 100 33721 Tampere, Finland

foocy@cbs.curtin.edu.au ABSTRACT

In current literature, grief play in Massively Multi-player Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs) refers to play styles where a player intentionally disrupts the gaming experience of other players. In our study, we have discovered that player experiences may be disrupted by others unintentionally, and under certain circumstances, some will believe they have been griefed. This paper explores the meaning of grief play, and suggests that some forms of unintentional grief play be called greed play. The paper suggests that greed play be treated as grieng, but a more subtle form. It also investigates the dierent types of grieng and establishes a taxonomy of terms in grief play.

Elina.M.Koivisto@nokia.com

gaming experiences. This type of play style is known as grief play, and grief players are known as griefers [11]. Surprisingly, although the term grief play is familiar to players and developers of MMORPGs, very little formal study has been conducted to investigate this behaviour. This paper attempts to dene grief play, and establish a taxonomy of its types. The intention of this paper is to assist both players and developers in understanding what it is.

2.

DATA COLLECTION

Categories and Subject Descriptors

J.4 [Social and Behavioral Sciences]: Sociology

General Terms

Human Factors

Keywords

MMORPG, game design, grief play, harassment, power imposition, scamming, greed play, avatars, role-play

1.

INTRODUCTION

Massively Multi-player Online Role-Playing Games, or MMORPGs, are large online worlds where players take on dierent roles and role-play their avatars. The subscriber bases of large MMORPGs each comprise players numbering in the hundreds of thousands. With so many players in the game, individual perceptions of what is fun in an MMORPG will logically vary. While the majority of players get along harmoniously, some players appear to engage instead in play styles that specically disrupt other players

The sources of data for this paper include a series of interviews conducted by Foo with a group of 31 respondents (comprising 18 non-grief players, 8 griefers, and 5 MMORPG developers), and discussion room postings from players. However, for the limited objectives of this paper, data was used from interviews primarily, with discussion postings used to validate the ndings. The mode of interview inquiry was semi-structured and through email, and ran from Sep 2003 to Jan 2004 with two to three questions per email. An average of 24 questions were asked per respondent, covering not only the denitional aspects of grief play, but also player expectations, griefer motivations, perceptions of game management, and player justice systems. Replies varied in length - some wrote sentences, others wrote pages. Also, both researchers are active players of MMORPGs, and care was taken to eliminate bias and personal opinion in the study. The resulting data was analysed in a qualitative manner.

3.

DEFINING GRIEFING

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for prot or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the rst page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specic permission and/or a fee. International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology ACE 2004, June 3-5, 2004, Singapore Copyright 2004 ACM 1-58113-000-0/00/0004 ...$5.00.

Studies of anti-social behaviour in multi-player role-playing games in the 90s were centred around Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs), comprising usually hundreds of users. MMORPGs tend to have much larger subscriber bases, coupled also with the added dimensions of avatar-based role-playing and graphical realism. Kim [7] notes the relationship between violence exhibited by griefers in the rst large MMORPG, Ultima Online (UO), and the existence of social communities in Britannia, its game world: The paradox of violence in online worlds is that while it generates moral outrage, it also encourages players to band together into tightly knit groups of trusted comrades. These groups - tribes, clans, families, or guilds - are what Britannian culture, and perhaps online culture in general, is really all about. Ever since the launch of UO in 1997, grief play has surfaced as an interest area to players and developers, evidenced

245

by the amount of discussion generated in online forums. Moreover, we believe a study of grief play will be of interest to academics researching on social conict in online communities. Grief can be dened as a source of deep mental anguish, annoyance or frustration [1]. Mulligan & Patrovsky [9] explain that a griefer is: A player who derives his/her enjoyment not from playing the game, but from performing actions that detract from the enjoyment of the game by other players. Key to this denition is that: 1. The griefers act is intentional; 2. It causes other players to enjoy the game less; 3. The griefer enjoys the act. There is evidence to suggest that the actual number of players who grief is really quite small - the statistic of 3 percent of players who grief was quoted in the Game Developers Conference 2002 [13]. However, Pham [11] notes that their play style aects players many times their numbers. Central to what makes an activity grieng is the presence of intent, which is noted by Mulligan & Patrovsky [9]. We observe this also in the responses of our interviewees, discussion room postings, and in the Rules of Conduct (ROC) of some games. Respondents do not seem to dispute the meaning of grief, nor the presence of intention to detract other players enjoyment1 .

action may cause others distress, it is not considered harassment until it is determined by OSI/EA that it was done to intentionally cause distress or to oend other players. To better illustrate the signicance of whether intention is critical in an act, two scenarios to show the relative absence of intent were posed to interview respondents: 1. A player with vendors somehow succeeds in cornering an important resource needed by players and is normally sold on NPC5 vendors, so that it no longer becomes available for sale on NPCs. Players can only buy the resource at increased prices, and the seller does this for the purpose of making large prots. 2. A player persistently camps a high level mob for an item he wants. But because his character isnt advanced enough, this mob kills the player, and proceeds to kill other neighbouring players. The others are unhappy and feel their gaming is being aected, but this player refuses to leave the area and continues to ght the high level mob, as he wants that item. Responses to the rst scenario suggested that if an activity is part of the game mechanic by design, then it would not be a grief tactic (R1). Moreover, this could be a case in which players have responded to incentives in the game to be protable, and while their method of gaining prot may have been unexpected (R3), it has not been with the specic intention of causing discomfort to other players. The second scenario drew varied responses, with one respondent (R15) suggesting that the player is repeatedly playing in a manner that poses signicant harm to other players. Hence, while his actions may not have been with the specic intention of distressing other players, that they have causes the act to be perceived as grieng, if a more ambiguous form of. Another respondent, a griefer (R10), even suggests that this scenario poses the potential for more grieng from surrounding players, if they initiate hostilities towards this ambitious player camping the mob. The dierence between the two scenarios lie in how much harm has been posed to players. The rst will inconvenience players, but the second can potentially kill their avatars. We believe grieng can be perceived in the second scenario in two ways: rstly, the actor engaging in dangerous activities is aware that his actions pose danger to other players. Secondly, the action continues to take place even after surrounding players have made known their displeasure (R30). The player base seems to be forgiving towards a player who may be unconscious of the dangers or risks his action exposes other players to. But if that action is repeated, even in the absence of a specic intention to grief, players will consider that act to be grieng (R27). While game management in MMORPGs do attempt to determine if there has been intention to grief when investigating an act, interview data suggests this is not easy. Unless the grief player has verbalised some part of his action (R1), or the action perpetuated is clearly providing minimal direct benet to him, whether the player is truly intending to distress or disrupt can be dicult to determine. Data in our study suggests, similarly, that some players regard as grieng any activity that interferes with their enjoyment of the game, regardless of any intention to distress or disrupt. While Mulligan & Patrovskys denition of grieng

5

3.1

The issue of intention

Data from our interviews initially suggested that respondents believe grief play is often intentional. Even then, after more in-depth investigation, we realised that some players believe that even if an action is permissible by game mechanics and the griefers foremost intention may not have been to cause distress to others, they will feel griefed if they have been annoyed or disturbed as a result of that action nonetheless. In other words, grieng may be unintentional, for example, as one respondent (R28)2 of UO cites an incident of a tamer with a pet he cannot properly control attacking the mobs3 already engaged by other players. Another player (R23) remarks that if an act has made it harder for other players to advance (in the game), it is grieng regardless of the presence of intent: When you camp4 out a spawn simply to collect the money and high end items you cause grief to other players because they never get a chance. To complicate matters further, the ROCs of some games suggest that the presence of intent is critical in the assessment of an act to see if grieng has taken place. For example, the Harassment Policy of UO [4] says: While an

1 Examples of respondent denitions can be found at http://www.chekyang.com/phd/gf/ act2004-grief-1.htm. 2 The interview material is not publicly available at the moment, and the identity of each respondent in the study is protected. The authors of this paper can be contacted if the reader would like to follow-up on interview data requests. In addition, for consistency, we will use the masculine form when referring to respondents, although both sexes were represented in our study. 3 Hostile creatures or computer controlled entities in the game. 4 Wait in the vicinity for a period of time where the item or mob is known to appear.

Non-player, or computer controlled, characters.

246

is appropriate in identifying purposeful grieng, we believe a distinction needs to be drawn to distinguish two types of grief play - the purposeful, and the more subtle kind. The rst type has the clear presence of intention to disrupt other players gaming experience, similar to that suggested by Mulligan & Patrovsky. The second type is ambiguous as there is no explicit intention to grief. The actor may be responding to incentives provided in the game to get ahead. However, by carrying out an action where the actor is the sole beneciary, that action could be seen as selsh, and potentially upset or harm other players. For this, we propose the term greed play, and suggest it be placed as a type of grief play. Another factor supporting our argument for distinction between these styles is the issue of player types. Bartle divides players into four categories: killers, socializers, explorers, and achievers [2], and we believe griefers are primarly killers and greed players achievers according to his player types. The principal dierence between grief and greed play, again, lie in how explicit is the intention to grief. With this in mind, we dene grief play as: Play styles that disrupt another players gaming experience, usually with specic intention to. When the act is not specically intended to disrupt and yet the actor is the sole beneciary, it is greed play, a subtle form of grief play. Our paper will elaborate in a later section the various types of grief play we have observed, and also greed play.

3.3

Grieng and rules

Salen & Zimmerman [14] write that there are three related levels of rules in a game - constituative rules which are the core mathematical rules, operational rules which are the rules of play that players follow, and implicit rules. For the purposes of our paper, we have adapted these to form three types of rules: Law of Code8 or what is allowed by program code. Rules found in the Terms of Services or ROCs accompanying MMORPG titles. Implicit rules which are the loosely dened, gamespecic social rules of fair-play and etiquette of that game. When game management employees, for example game masters, investigate if grieng has occurred in an incident, of signicant concern is if rules, particularly of the rst two types above, have been broken. Rules, however, dier from game to game. A play style that is disallowed and used as a method for grieng in one could be regarded as an acceptable game tactic in another. For example, player blocking is allowed in UO [4] but not in EverQuest (EQ) [15]. Restrictions on a play style are either implemented in the Law of Code - which makes it normally impossible for players to get round, unless loopholes are exploited - or governed by the ROC, which players are required to follow. Harder to enforce, however, are the implicit rules, which tend to be nebulous and may be subjective for dierent players. Moreover, a new play style could be perceived as grieng according to implicit rules, but could come to be regarded as a legitimate play style if it becomes commonplace or as the player base matures. ROCs, however, routinely include a catch all which states - often in broad terms - that a player may not play the game in a way that inhibits the enjoyment of other players. For example, in Dark Age of Camelot (DAoC): Player may not engage in any conduct or communication while using the DAoC Services which is unlawful or which restricts or inhibits any other Player from using or enjoying these Services. [10] Players will often employ implicit rules when assessing if they have been griefed by a play style, while game management will base their consideration on Law of Code and ROCs.

3.2

Other characteristics of grieng

In grief play, and to a lesser extent greed play, the griefer enjoys the act and attention. The presence of web sites that relate the exploits of griefers6 suggest that griefers are unabashed about their activities. This behaviour is similar to teasing - Feinberg [5] suggests that a teaser through the exercising of his wit, intelligence, and imagination gets the attention he wants. One player also notes that the determinant to whether a grieng activity is successful is based on the reactions of the people suering from the griefers actions, and not merely from the accomplishment of whatever is being done (R30). In addition, several respondents revealed incidents where they were griefed either as new players, or when their characters were in vulnerable states. The griefer is typically more powerful than the victim in terms of character advancement, assets and equipment owned, and often a more experienced player. This makes it dicult for the victim to retaliate (R15). Moreover, when asked if griefers enjoy being attacked in return in a Player versus Player7 (PvP) setting, one griefer (R12) remarks: Griefers dont want retaliation. If there was, they could not grief as much and the whole purpose to be a griefer is to cause grief and get away with it. This is not to suggest that all griefers avoid retaliation. For some, it is an added challenge when their victims attempt to defend themselves (R6). In addition, it could be a signal to the griefer that his eort to annoy has been succesful if the victims have been suciently distressed to take action. For example http://galad.griefgaming.com. Refers to situations where players engage in combat against other players.

7 6

4.

A TAXONOMY FOR GRIEF PLAY

Based on our data, we suggest four categories of grieng: harassment, power imposition, scamming, and greed play9 . The four categories dier along these criteria: 1) how explicit is the intent to grief when in that play style; 2) the kind of rules the play style breaks; 3) developer and player perceptions of the play style. We will add a note on game exploitation here. While perceptions among players and developers dier on what kind of play style is grieng, game exploitation is seen with disdain by players, and disallowed by game management altogether. For example, in EQs ROC:

8 The term code is law is used in Lawrence Lessigs book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace [8]. 9 More detail on grief play types and their relation to rules can be found at http://www.chekyang.com/phd/gf/act2004-grief-1.htm.

247

You will not exploit any bug in EverQuest and you will not communicate the existence of any such exploitable bug (bugs that grant the user unnatural or unintended benets in game), either directly or through public posting, to any other user of EverQuest. [15] Game exploitation is associated with grieng when exploits are used to facilitate or enhance the eects of a grieng act. For example, a player who is blocking another players way in a Player versus Environment10 (PvE) setting with the intention of getting him killed by monsters could be exploiting loopholes in the game. This is assuming that this is a play style that has not been considered in design earlier on and code written in to make such behaviour impossible. Even then, game exploitation may occur separately from a grieng action. The exploiters intent may be to benet purely from the deciencies of game design or code and not to grief, even if the eects of that exploitation may aect indirectly the gaming experience of other players.

utes. Often, griefers either disrupt events directly by spamming chat messages that violate the spirit of the event, or engage in destructive action to upset the arrangement or organization of the event. Moreover, because MMORPGs are social systems and not just games [12], ways of harassment that are possible in real life are possible in the game as well; for example stalking, eavesdropping and threatening.

4.2

Power imposition

4.1

Harassment

In harassment, the griefers intention is to cause emotional distress to the victim. Aside from the enjoyment of seeing the victim suer, the griefer does not benet from the action otherwise. In some instances, harassment can be without the intention to grief if the actor does not know his behaviour upsets other players, for example by using a term in his speech or in his character name that may be racially oensive to a particular group of players. Regardless, if the player has been asked to stop using this term but does not do so, it could be reasonable to conclude that the player is grieng, regardless of initial intent. The ROCs of many MMORPGs prohibit harassment strictly. Of harassment types, shouting slurs is a common way to harass other players. This type of behaviour is often easy for game management to prosecute as chat messages can be logged for further investigation. The player may also intentionally spam a chat channel repeatedly with messages of low relevance or utility. Players may also emote in an oensive way, for example when performing a so-called virtual rape of a victim in the game (R20). MMORPGs often allow players to ignore chat messages from specic players, or engage profanity lters. Spatial intrusion occurs when a player repeatedly violates the space perceived to be private to another player even when he is requested to stop. For example, a griefer can enter a player-owned house or establishment and proceed to make a nuisance by spamming slurs. One player (R24) of UO relates the following: Some punk kid came along one day and ran inside my house as I was coming out. He stood in the doorway, holding the door open and called to passers by come on in and take anything you want for free! ... I killed him three times (trashing my reputation) and he just rezzed [resurrected] himself back in my house and continued the harassment. Game design improvements since then allow the owner of a player establishment to better manage who gets access into the property. Event disruption occurs when an event organized by players is purposefully interrupted by other players. One player (R27) of UO relates an event, called The Trinsic incident, where a large role-playing event was griefed by 5 players, resulting in the event being called o after 15 min10

Refers to players engaging agents which are not controlled by other players but by the game environment.

The demonstration of power in itself is not perceived by players as grieng. But when power superiority is manifested through other actions, for example certain types of player killing, or coupled with other grieng types, for example harassment, it is. Some developers feel that a play style is not a grieng tactic if it is allowed by game design and code (R1). If PvP combat is allowed in a game and players are ambushed and killed unexpectedly, the ROC does not typically regard this as grieng. Moreover, player killing may be motivated by a desire other than to impose power over the victim - for example because the game by design encourages consensual player killing in the form of player faction conict. However, data suggests that the particular circumstance of a player killing may cause the victim to believe he has been griefed. A player (R23) of UO relates the following encounter with a griefer: He invited us over to see his house and we agreed, as he seemed like a nice guy. Once close to his house he turned around and attack us. My friend fell rst and then I fell next. He looted our things and refused to resurrect us. When we nally did get resurrected, we went back to my friends house only to be killed again. We were killed by him 4 times that night. In this case, the respondents character was killed repeatedly. In addition, several respondents also related incidents where their characters were killed when helpless (for example having just combatted a tough mob and leaving the character in a weakened state), new or very inexperienced, with verbal abuse often accompanying the act. Moreover, the use of loopholes to cause the death of another players character will likely add to perception that the player has been griefed with underhand methods. To put it another way, regardless of the Law of Code, the act of killing another player could be perceived to be grieng if: 1) the victims death oers little or no direct benet outside faction PvP to the player; 2) verbal abuse accompanies the act; 3) the act is repeated several times; or 4) the act is facilitated through the use of loopholes. Similarly, rez killing and newbie killing are perceived to be grief play if the player does not signicantly benet from the action, regardless of the Law of Code. In rez killing, the griefer rst resurrects the victim and after that kills him again, doing so repeatedly. Newbie killing refers to the killing of new and frequently inexperienced players for fun, even though there is little direct benet from attacker to the victim. Other more subtle ways to impose power include training and player blocking. Training is dened as pulling/leading a hostile NPC or creature along behind you and attempting to get it to attack another player who does not desire that engagement. [16] In EQ, a player seeking to escape from a mob in a high level dungeon could accidentally lead this and other mobs to nearby players, resulting in an unintentional train. We suggest that only intentional training constitutes

248

grieng. Player blocking refers to the obstruction of another players escape path and causing the characters death. In both cases, the griefer feels powerful for having caused the deaths of other players, as he has demonstrated superior knowledge of game mechanics and has manipulated game code limitations.

Also, ROCs do not usually explicitly disallow the impersonation of another players character, although this is not easy unless the griefer has designed his character to physically resemble the targeted victim in outward appearance, and chosen a name that is the same or close to the victims. ROCs do disallow the theft of player accounts, and explicitly disallow the impersonation of game company employees.

4.3

Scamming

A scam refers to a fraudulent business scheme or a swindle [1]. Data suggests signicant disagreements on whether it really is grieng. The root of this lies in the role-playing context of a MMORPG, and some players expect to be able to role-play unsavoury characters. In our study, the following scenario was posed to respondents: A players character is a thief, and this is visibly tagged on this character for all to see. What if this person scams another player, but when queried by the game master, he insists he was role-playing in a manner consistent to that of a thief ? Data suggests that some players believe player transactions should operate on caveat emptor (let the purchaser beware), with one respondent even remarking: This is not grief play, but smart play on the part of the thief and dumb play on the part of the buyer. (R25) Moreover, it is not easy to code mechanisms that can determine a sellers trustworthiness. On the other hand, others believe that there are some actions in a game that are to occur out of character - and player sales and transactions are in this exception list. One player of EQ (R16) says: When people barter, they drop out of role-play mode. Its implied that any trade agreement they are making is made in good faith. The developers interviewed say that the above type of role-playing scenario is tricky. As before, if the game by design supports a play style that rewards players for getting ahead, can players who turn dishonest really be called griefers? On the other hand, several developers believe that more often than not, a player who claims he is role-playing is more likely attempting to get away with misbehaviour than demonstrating any true role-playing on his part. Moreover, ROCs in EQ [15] and Star Wars Galaxies (SWG) [16] disallow fraud, and add that role-playing does not excuse such behaviour. Scamming is considered to be grieng when it is exploitative of poorly designed trading systems, which may enable trade scamming. Many current MMORPGs use secure trade windows for player trading, which require players to give explicit consent for item and money exchanges before the transaction is completed. What they are less eective in preventing are scams from promise breaking. This occurs when the other player promises to do something, for example render a service or sell an item outside the trade window - but upon the exchange of monies, the player does not full his promise. Identity deception occurs when a player attempts to deceive by presenting himself as someone else. While identity deception is common in Internet groups and games [3], the context of an MMORPG suggests that identity deception can possibly be seen as true role-playing rather than grieng. For example, a player could attempt to portray himself of the opposite gender, dierent age, or other personality traits, with the intention of being consistent with the type of character being role-played. When it could become grieng is if the impersonation is with the intent to actively deceive, abuse or scam disguised as someone else.

4.4

Greed play

The players motive in greed play is to benet, regardless if the action annoys the other players around him. The unsportsmanlike behaviour described in Salen & Zimmermans book [14] is similar to greed play - the actor will do anything to win; he follows the operational rules of a game, but violates the spirit of the game and its implicit rules. Our discussion in section 3.1 has suggested varied opinion over whether greed play constitutes grieng, since there is an absence of an explicit intention to disrupt. The intention here is to get ahead. Hence, should players be faulted if the game encourages them as a result to do so, for example, by allowing more powerful players access to additional play areas? Data suggests that players are forgiving if greed play is merely inconveniencing them, for example in the hoarding of resources. On the other hand, data also reveal that players are still upset at such behaviour, and are likely to consider it to be a subtle form of grieng when the act poses direct risk or causes harm to their avatars. One common form of greed play is ninja looting, which Mulligan & Patrovsky [9] dene as taking loot that was earned by another player, by speed, guile, or a cheat. Typically, a player quickly loots mob corpses that he should not be looting. This could be because rstly, he did not participate in the ght; or secondly, he participated as part of the team but had insignicant contribution; or thirdly, he is part of the team but someone else has already been assigned to loot the mob. The rst kind of ninja looting can be prevented in code, as looting rights can be awarded only to the player or team who succeeds in administering the most damage. However, this may encourage griefers to kill steal (see below) and then loot the mob immediately after the battle. If no such damage-based looting code exist, it could encourage players in the vicinity to all have a go at a mob when it appears since they all have some chance of getting looting rights. The second kind is harder to prevent through game design, as it is less easy to code a mechanism that will fairly determine looting rights based on contribution within a team, since support-class players - for example healers - are less likely to administer direct damage. Some MMORPGs allow looting rights to designated with the group; with Anarchy Onlines ROC [6] even stating that looting disputes within a team are not considered ninja looting. Kill stealing refers to an action where a player attempts to gain benet by participating in the killing of a mob that is already engaged in a ght with another player or team. A player of DAoC (R18) shares the following: This player came along and asked to join us... But he was about 6 levels lower than all of us and wouldnt be able to help the group much and would only leech our xp, so we politely declined. He got oended and started shooting at the mobs we were killing, boasting about the damage he was doing. Like ninja looting, kill stealing as a form of greed play is recognized as a disruptive and annoying type of behaviour, with divided perception whether it is explicit grieng since

249

it does not normally result in player deaths. Moreover, if the mob carries a highly contested item, some players believe they are justied in engaging in competitive behaviour for it. For example, for a short period of time in SWG, erce competition for an item known as the Holocron resulted in large groups of players continuously camping known spots spawning mobs that carry the item. When the mob appeared, surrounding players abandoned any prior arrangements of turn taking, and attacked the mob simultaneously in a frenzy, all hoping to get the required looting rights. Some players regarded this as grieng, while others did not (R20). Data suggests that kill stealing may be regarded as griefing when the actor is grossly over powered in relation to the mobs prowess and the already engaged players or teams collective abilities. For example, a team of low level players ght a mob, and midway a highly powered player without invitation engages the same mob, killing it quickly. Typically, whether this mob will grant this highly powered character any loot is a moot issue - the signicant power level dierence between the high level character and mob causes surrounding players to perceive grieng has occurred, since this player has defeated the mob with little risk or eort involved. Area monopolising takes place when a player or a group demands exclusive access to an area, for example in order to be sole occupants to an area where a mob or resource appears. One way to monopolise areas is camping, often with the intention of repeatedly obtaining experience or items in the most ecient way possible (farming). Camping is considered as valid play rather than grieng, and players are occasionally required by ROCs to share areas, for example in EQs [15] play-nice rules. Even then, unless the new group has come to some mutual arrangement at turn taking with the group already present, when the mob appears, this occasionally results in chaos as both groups scramble to ght. On other occasions, a highly powered character could be farming a weaker mob producing an item, and the weaker players have no reasonable chance of contesting and defeating the same mob under such competition. Again, there may not have been a specic intention to grief, but some players become annoyed and feel that this is not fair play.

holes in code exploited when investigating grieng. Moreover, rules dier from game to game. What could be grieng in one may be a legitimate play tactic in another. In some games which are dominantly PvP, a player is provided the means to resolve acts of grieng himself - usually by attacking the griefer. Alternatively, some grief play types can be prevented in game design, for example through the inclusion of secure trading systems. Some games also allow players to reduce the eect of grieng - for example profanity lters, ignore player options, and house management. On the other hand, other grief play types are harder to prevent, for example activities that depend on a players trustworthiness. We believe this paper has shown that there is a wealth of information and range of perceptions about grieng among players and developers, and we believe more work is needed in this area to better understand grief play. We will be continuing our research to investigate grief player motivations, its eects on the game world and players, player perceptions of game management, and if grief play can be better managed altogether.

6.

REFERENCES

5.

CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this paper has been to dene grief play and provide a taxonomy for its types in the context of a MMORPG. An important issue in our study has been the intention on the actors part to disrupt another players enjoyment of the game. This is not always easy to determine, unless other actions accompany the act. Moreover, though players and developers frequently regard grieng as intentional, data suggests that some players regard play styles where the actor is the sole beneciary as grieng, regardless of intention to disrupt or distress. We call these activities greed play, and suggest it to be treated as a form of griefing. In the eyes of players, an activity is clearly grieng if the actor has little direct gain from the act, or if the act is repeated, or if another grieng type accompanies the act. Victims often nd it dicult to oppose grieng or defend themselves as well. On the other hand, game management is more concerned if rules of conduct have been broken or loop-

[1] The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language 2000. Houghton Miin Company, Address, 2000. [2] R. Bartle. Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit muds. Journal of Mud Research, 1997. [3] J. Donath. Identity and deception in the virtual community. Communities in cyberspace: perspectives on new forms of social organization, 1997. [4] Electronic Arts. Service and payment information. 2003. http://support.uo.com. [5] L. Feinberg. Teasing: Innocent fun or sadistic malice. New Horizon Press, New Jersey, 1996. [6] Funcom. Rules of conduct within Anarchy Online. 2004. http://www.anarchyonline.com. [7] A. J. Kim. Killers have more fun. Wired News, May 1998. [8] L. Lessig. Code and other laws of cyberspace. Basic Books, New York, 1999. [9] J. Mulligan and B. Patrovsky. Developing online games: an insiders guide,. New Riders, Indiana, 2003. [10] Mythic Entertainment. Rules of conduct policy. 2001. http://support.darkageofcamelot.com. [11] A. Pham. Online bullies give grief to gamers. Los Angeles Times, September 6 2002. [12] Pika. Interview with Raph Koster, chief creative ocer of SOE. Warcry News Network, February 2 2004. http://www.xrgaming.net. [13] P. Pizer. Social game systems: cultivating player socialization and providing alternate routes to game rewards. Charles River Media, Massachusetts, 2003. [14] K. Salen and E. Zimmerman. Rules of play: game design fundamentals. MIT Press, Cambridge, 2004. [15] Sony Online Entertainment Inc. Everquest rules of conduct. 2001. http://eqlive.station.sony.com. [16] Sony Online Entertainment Inc. Policies: community standards. 2004. http://starwarsgalaxies.station.sony.com.

250

You might also like

- Guard IwDocument4 pagesGuard IwtramenesNo ratings yet

- Lapdijszabas - 20240301 Eng ONLINEDocument2 pagesLapdijszabas - 20240301 Eng ONLINEtramenesNo ratings yet

- Kome Paper 2021Document24 pagesKome Paper 2021tramenesNo ratings yet

- MTG TáblaDocument31 pagesMTG TáblatramenesNo ratings yet

- A Case For Psychoanalytic Visual "Cinematographic Capture": Dispositif? Birdman After TheDocument16 pagesA Case For Psychoanalytic Visual "Cinematographic Capture": Dispositif? Birdman After ThetramenesNo ratings yet

- Please Feel Free To Set Up An Appointment If You Can't Make This TimeDocument5 pagesPlease Feel Free To Set Up An Appointment If You Can't Make This TimetramenesNo ratings yet

- Another Rainy Night - Patrick GoodmanDocument19 pagesAnother Rainy Night - Patrick Goodmantramenes100% (1)

- Dave Morris Heart of IceDocument149 pagesDave Morris Heart of Icetramenes100% (1)

- Non OrthodoxDocument93 pagesNon OrthodoxBigfetaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ExamDocument446 pagesExamkartikNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence/Search/Heuristic Search/astar SearchDocument6 pagesArtificial Intelligence/Search/Heuristic Search/astar SearchAjay VermaNo ratings yet

- PDF Applied Failure Analysis 1 NSW - CompressDocument2 pagesPDF Applied Failure Analysis 1 NSW - CompressAgungNo ratings yet

- The World Wide WebDocument22 pagesThe World Wide WebSa JeesNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0959652618323667 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0959652618323667 MaintaliagcNo ratings yet

- Tapspp0101 PDFDocument119 pagesTapspp0101 PDFAldriel GabayanNo ratings yet

- 5 Axis Lesson 2 PDFDocument36 pages5 Axis Lesson 2 PDFPC ArmandoNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To SAP Business One CloudDocument14 pagesAn Introduction To SAP Business One CloudBharathkumar PalaniveluNo ratings yet

- 8051 Development Board Circuit DiagramDocument1 page8051 Development Board Circuit DiagramRohan DharmadhikariNo ratings yet

- International Advertising: Definition of International MarketingDocument2 pagesInternational Advertising: Definition of International MarketingAfad KhanNo ratings yet

- San Miguel ReportDocument8 pagesSan Miguel ReportTraveller SpiritNo ratings yet

- ADMS 2510 Week 13 SolutionsDocument20 pagesADMS 2510 Week 13 Solutionsadms examzNo ratings yet

- Design of Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion Cages With Various Infill Pattern For 3D Printing ApplicationDocument7 pagesDesign of Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion Cages With Various Infill Pattern For 3D Printing ApplicationdhazliNo ratings yet

- SIConitDocument2 pagesSIConitJosueNo ratings yet

- Canon IR2016J Error Code ListDocument4 pagesCanon IR2016J Error Code ListZahidShaikhNo ratings yet

- Social and Prof Issues Module2Document31 pagesSocial and Prof Issues Module2Angelo NebresNo ratings yet

- The US Navy - Fact File - MQ-8C Fire ScoutDocument2 pagesThe US Navy - Fact File - MQ-8C Fire ScoutAleksei KarpaevNo ratings yet

- Management Thoughts Pramod Batra PDFDocument5 pagesManagement Thoughts Pramod Batra PDFRam33% (3)

- EECI-Modules-2010Document1 pageEECI-Modules-2010maialenzitaNo ratings yet

- BF2207 Exercise 6 - Dorchester LimitedDocument2 pagesBF2207 Exercise 6 - Dorchester LimitedEvelyn TeoNo ratings yet

- Computing The Maximum Volume Inscribed Ellipsoid of A Polytopic ProjectionDocument28 pagesComputing The Maximum Volume Inscribed Ellipsoid of A Polytopic ProjectiondezevuNo ratings yet

- a27272636 s dndjdjdjd ansjdns sc7727272726 wuqyqqyyqwywyywwy2ywywyw6 4 u ssbsbx d d dbxnxjdjdjdnsjsjsjallospspsksnsnd s sscalop sksnsks scslcoapa ri8887773737372 d djdjwnzks sclalososplsakosskkszmdn d ebwjw2i2737721osjxnx n ksjdjdiwi27273uwzva sclakopsisos scaloopsnx_01_eDocument762 pagesa27272636 s dndjdjdjd ansjdns sc7727272726 wuqyqqyyqwywyywwy2ywywyw6 4 u ssbsbx d d dbxnxjdjdjdnsjsjsjallospspsksnsnd s sscalop sksnsks scslcoapa ri8887773737372 d djdjwnzks sclalososplsakosskkszmdn d ebwjw2i2737721osjxnx n ksjdjdiwi27273uwzva sclakopsisos scaloopsnx_01_eRed DiggerNo ratings yet

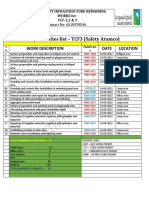

- Daily Activities List - TCF3 (Safety Aramco) : Work Description Date LocationDocument2 pagesDaily Activities List - TCF3 (Safety Aramco) : Work Description Date LocationSheri DiĺlNo ratings yet

- RRB NTPC Previous Year Paper 20: WWW - Careerpower.inDocument16 pagesRRB NTPC Previous Year Paper 20: WWW - Careerpower.inSudarshan MaliNo ratings yet

- Rhea Huddleston For Supervisor - 17467 - DR2Document1 pageRhea Huddleston For Supervisor - 17467 - DR2Zach EdwardsNo ratings yet

- Media DRIVEON Vol25 No2Document21 pagesMedia DRIVEON Vol25 No2Nagenthara PoobathyNo ratings yet

- User's Guide: Smartpack2 Master ControllerDocument32 pagesUser's Guide: Smartpack2 Master Controllermelouahhh100% (1)

- Fashion Law - Trademark ParodyDocument12 pagesFashion Law - Trademark ParodyArinta PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Simple Usecases of PI B2B - SFTP and PGPDocument35 pagesSimple Usecases of PI B2B - SFTP and PGPPiedone640% (1)

- Arti ResearchDocument10 pagesArti Researcharti nongbetNo ratings yet