Professional Documents

Culture Documents

So What Were My Impressions

Uploaded by

Cel PenarandaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

So What Were My Impressions

Uploaded by

Cel PenarandaCopyright:

Available Formats

So what were my impressions? First, Mead had a captivating writing style and a real gift for painting scenes.

From the first pages, I could almost envision the Samoan village she described based on her study in 1925-1926. Mead introduces us to the scene first, then takes us through the contextual information in subsequent chapters: a typical Samoan day, children's education, the household, how adolescent girls related to their age groups and community, then issues such as sex relations, dance, and personality. In all these chapters, we almost feel like we have entered village life, learning the hierarchy, seeing the interactions, and being privy to the gossip: who is lazy, who is slow, who has poise and maturity beyond her years, who lags behind, who slept with whom. Mead gives many quotes, but far more stories about the happenings in the three villages she studied. This description sounds like the sort of thing that two or three teenage girls might say about a rival. Did Mead triangulate this description with others in the village, including children and adults? Did she interview Sala herself about her own impressions? Unfortunately it's impossible to say. Sala does appear in the table of participants in the back, but in my reading, I didn't see any other information about where she got this description beyond "it was a saying among the girls of the village..." In fact, the methodology was rather spare. Mead characterizes Samoa's adolescent girls on the basis of "six months" spent "in one small locality, in a group numbering only six hundred people" in "three practically contiguous villages" (p.145). (Elsewhere, Mead puts the total time in Samoa at nine months.) That's a very short period for an ethnography, especially given that Mead had to gain the trust of her informants. Mead ends with a couple of chapters that attempt to apply the lessons of Samoa to childrearing and education in the West. In these chapters, she paints a rather idyllic picture of Samoan life and especially Samoan adolescence, contrasting it sharply with those of the West, and suggesting that much of the difference comes from the fact that Samoan life is much more heterogeneous than life in the West (pp.112113) and that Samoan children are given more choices, particularly in their sexual experiences. An aside: modern readers will be taken aback by some of the language used in this 1928 book. For instance, Mead uses the term "savages," a jarring term in 2011. Similarly, Mead allows that adolescents regularly engage in "homosexual" behavior as part of their development and advancement into adulthood, but she draws a bright line between this experimentation and "perversion," i.e., lifelong same-sex orientation (p.82). Again, the terms are jarring, and may be difficult for the reader of 2011 to get past.

Overall, I was suspicious of Mead's conclusions, based on her small amount of time among the Samoans, the idyllic picture she painted of them, and the methodology she used, which seemed to rely heavily on interviewing teen girls and very lightly on triangulating these impressions via observations, artifacts, or interviews with other groups. It's still a fascinating and well written study, but I wouldn't encourage anyone to model their own studies based on it. I would, however, encourage them to read it.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- IELTS Test 101Document11 pagesIELTS Test 101Aline LopesNo ratings yet

- Autobiography EssayDocument7 pagesAutobiography Essayapi-533899699No ratings yet

- Action Plan in EnglishDocument2 pagesAction Plan in EnglishJon Vader83% (6)

- Admin Law Quiz 1 AnswersDocument4 pagesAdmin Law Quiz 1 AnswersShane Nuss RedNo ratings yet

- This Is A Design Portfolio.: - Christina HébertDocument28 pagesThis Is A Design Portfolio.: - Christina HébertChristinaNo ratings yet

- Gender Bias and Gender Steriotype in CurriculumDocument27 pagesGender Bias and Gender Steriotype in CurriculumDr. Nisanth.P.M100% (2)

- AFHS Admission EnquiryDocument2 pagesAFHS Admission EnquiryPassionate EducatorNo ratings yet

- Math IaDocument10 pagesMath Iaapi-448713420No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan English 10Document6 pagesLesson Plan English 10Butch RejusoNo ratings yet

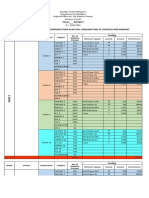

- Palo - District: Week School Grade Level Subject No. of Modules PrintedDocument5 pagesPalo - District: Week School Grade Level Subject No. of Modules PrintedEiddik ErepmasNo ratings yet

- A Template To Be Used by The Students For Typesetting Project Report or DissertationDocument18 pagesA Template To Be Used by The Students For Typesetting Project Report or DissertationMuhammad Tanzeel Qaisar DogarNo ratings yet

- Envision Hilltop 2020Document196 pagesEnvision Hilltop 2020Neighborhood Design CenterNo ratings yet

- Teacher's and Student's CenterDocument21 pagesTeacher's and Student's CenterNusrat Bintee KhaledNo ratings yet

- Global PerspectiveDocument47 pagesGlobal PerspectiveRenato PanesNo ratings yet

- 101-WPS OfficeDocument1 page101-WPS OfficeVia Cortez OdanNo ratings yet

- Transfer Certificate SampleDocument1 pageTransfer Certificate Sampleashutosh SAKNo ratings yet

- SLS Instructors Guidelines Manual 10-06Document29 pagesSLS Instructors Guidelines Manual 10-06kshepard_182786911No ratings yet

- Names NarrativeDocument23 pagesNames NarrativeJanine A. EscanillaNo ratings yet

- BP Cat Plan Risk AssesDocument36 pagesBP Cat Plan Risk AssesErwinalex79100% (2)

- Research Paper 1Document20 pagesResearch Paper 1api-269479291100% (2)

- Preventive Conservation A Key Method ToDocument15 pagesPreventive Conservation A Key Method ToSabin PopoviciNo ratings yet

- Development Shobhit NirwanDocument11 pagesDevelopment Shobhit NirwanTarun JainNo ratings yet

- July 02, 2019 - Enrichment Activity On Pure Substances and MixturesDocument3 pagesJuly 02, 2019 - Enrichment Activity On Pure Substances and MixturesGabriela FernandezNo ratings yet

- Mte K-Scheme Syllabus of Civil EngineeringDocument1 pageMte K-Scheme Syllabus of Civil Engineeringsavkhedkar.luckyNo ratings yet

- 01CASE 1 PBW Thats The WayDocument11 pages01CASE 1 PBW Thats The WayHitesh DhingraNo ratings yet

- Adapted Physical Education PDFDocument1,264 pagesAdapted Physical Education PDFSherilyn Em Bobillo94% (17)

- Practice 3 Assessment - TeamDocument20 pagesPractice 3 Assessment - TeamTrang Anh Thi TrầnNo ratings yet

- Parental Involvement Questionare PDFDocument11 pagesParental Involvement Questionare PDFAurell B. SantelicesNo ratings yet

- Read Aloud Lesson Plan Kindergarten AutorecoveredDocument6 pagesRead Aloud Lesson Plan Kindergarten Autorecoveredapi-455234421No ratings yet

- Contrasting Disciplinary - Models.in - EducationDocument7 pagesContrasting Disciplinary - Models.in - EducationFarah Najwa Othman100% (1)