Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nasogastric Tube Insertion

Uploaded by

Diane Kate Tobias MagnoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nasogastric Tube Insertion

Uploaded by

Diane Kate Tobias MagnoCopyright:

Available Formats

Nasogastric Tube Insertion

Indications By inserting a nasogastric tube, you are gaining access to the stomach and its contents. This enables you to drain gastric contents, decompress the stomach, obtain a specimen of the gastric contents, or introduce a passage into the GI tract. This will allow you to treat gastric immobility, and bowel obstruction. It will also allow for drainage and/or lavage in drug overdosage or poisoning. In trauma settings, NG tubes can be used to aid in the prevention of vomiting and aspiration, as well as for assessment of GI bleeding. NG tubes can also be used for enteral feeding initially. Contraindications Nasogastric tubes are contraindicated in the presence of severe facial trauma (cribriform plate disruption), due to the possibility of inserting the tube intracranially. In this instance, an orogastric tube may be inserted. Complications The main complications of NG tube insertion include aspiration and tissue trauma. Placement of the catheter can induce gagging or vomiting, therefore suction should always be ready to use in the case of this happening. Universal precautions: The potential for contact with a patient's blood/body fluids while starting an NG is present and increases with the inexperience of the operator. Gloves must be worn while starting an NG; and if the risk of vomiting is high, the operator should consider face and eye protection as well as a gown. Trauma protocol calls for all team members to wear gloves, face and eye protection and gowns. Equipment: All necessary equipment should be prepared, assembled and available at the bedside prior to starting the NG tube. Basic equipment includes: Personal protective equipment NG/OG tube Catheter tip irrigation 60ml syringe Water-soluble lubricant, preferably 2% Xylocaine jelly Adhesive tape Low powered suction device OR Drainage bag Stethoscope Cup of water (if necessary)/ ice chips Emesis basin pH indicator strips

Procedures: 1. Gather equipment 2. Don non-sterile gloves 3. Explain the procedure to the patient and show equipment 4. If possible, sit patient upright for optimal neck/stomach alignment 5. Examine nostrils for deformity/obstructions to determine best side for insertion 6. Measure tubing from bridge of nose to earlobe, then to the point halfway between the end of the sternum and the navel 7. Mark measured length with a marker or note the distance 8. Lubricate 2-4 inches of tube with lubricant (preferably 2% Xylocaine). This procedure is very uncomfortable for many patients, so a squirt of Xylocaine jelly in the nostril, and a spray of Xylocaine to the back of the throat will help alleviate the discomfort. 9. Pass tube via either nare posteriorly, past the pharynx into the esophagus and then the stomach. Instruct the patient to swallow (you may offer ice chips/water) and advance the tube as the patient swallows. Swallowing of small sips of water may enhance passage of tube into esophagus. If resistance is met, rotate tube slowly with downward advancement toward closes ear. Do not force. 10. Withdraw tube immediately if changes occur in patient's respiratory status, if tube coils in mouth, if the patient begins to cough or turns pretty colours 11. Advance tube until mark is reached 12. Check for placement by attaching syringe to free end of the tube, aspirate sample of gastric contents. Do not inject an air bolus, as the best practice is to test the pH of the aspirated contents to ensure that the contents are acidic. The pH should be below 6. Obtain an x-ray to verify placement before instilling any feedings/medications or if you have concerns about the placement of the tube. 13. Secure tube with tape or commercially prepared tube holder 14. If for suction, remove syringe from free end of tube; connect to suction; set machine on type of suction and pressure as prescribed. 15. Document the reason for the tube insertion, type & size of tube, the nature and amount of aspirate, the type of suction and pressure setting if for suction, the nature and amount of drainage, and the effectiveness of the intervention.

Peripheral Intravenous Access

Introduction: The ability to obtain intravenous (IV) access is an essential skill in medicine and is performed in a variety of settings by paramedics, nurses and physicians. Although the procedure can appear deceptively simple when performed by an expert, it is in fact a difficult skill which requires considerable practice to perfect. The rate of fluid flow is proportional to radius to the power of four, and inversely proportional to length; therefore fluids run fastest through a shorter and larger diameter tube. Also note that the smaller the gauge of a needle, the larger its diameter i.e. a 14 gauge needle has larger diameter than a 21 gauge needle. Indications By starting a peripheral IV, you gain access to the peripheral circulation of a patient, which will enable you to sample blood as well as infuse fluids and IV medications. IV access is essential to manage problems in all critically ill patients. High volume fluid resuscitation may be required for the trauma patient, in which case at least two large bore (14-16 G) IV catheters are usually inserted. All critically ill patients require IV access in anticipation of future potential problems, when fluid and/or medication resuscitation may be necessary. Contraindications Some patients have anatomy that poses a risk for fluid extravasation or inadequate flow and peripheral IVs should be avoided in these situations. Examples include extremities that have massive edema, burns or injury; in these cases other IV sites need to be accessed. For the patient with severe abdominal trauma, it is preferable to start the IV in an upper extremity because of the potential for injury to vessels between the lower extremities and the heart. For the patient with cellulitis of an extremity, the area of infection should be avoided when starting an IV because of the risk of inoculating the circulation with bacteria. As well, an extremity with an indwelling fistula or on the same side of a mastectomy (occasionally a problem) should be avoided because of concerns about adequate vascular flow. Complications The main complications of an IV catheter are infection at the site and development of superficial thrombophlebitis in the vein that is catheterized. It is also common for the IV sites to leak interstitially. Important: Recapping needles, putting catheters back into their sheath or dropping sharps to the floor (an unfortunately common practice in trauma) should be strictly avoided. Recapping of needles is one of the commonest causes of preventable needle stick injuries in health care workers. Peripheral IV sites Generally IV's are started at the most peripheral site that is available and appropriate for the situation. This allows cannulation of a more proximal site if your initial attempt fails. If you puncture a proximal vein first, and then try to start an IV distal to that site, the fluid may leak from the injured proximal vessel. The preferred site in the emergency department is the veins of the forearm, followed by the median cubital vein that crosses the antecubital fossa. In trauma patients, it is common to go directly to the median cubital vein as the first choice because it will accommodate a large bore IV and it is generally easy to catheterize. In circumstances where the veins of the upper extremities are inaccessible, the veins of the dorsum of the foot or the saphenous vein of the lower leg can be used. In circumstances in which no peripheral IV access is possible a central IV can be started.

Equipment All necessary equipment should be prepared, assembled and available at the bedside prior to starting the IV. Basic equipment includes: gloves and protective equipment appropirate size catheter 14-25 G IV catheter non-latex tourniquet alcohol swab/other cleaning instrument non-sterile 2x2 gauze sterile 2x2 gauze (this is not practiced in nursing) 6x7cm Tegaderm Transparent Dressing 3 pieces of 2.5 cm tape approximately 10 cm in length IV bag with solution set (tubing) (flushed and ready) or saline lock sharps container

To prepare the IV line, protective caps are removed from the fluid bag and the spiked end of the IV tubing. The regulating clamp for the IV line should be closed. The spiked end of the IV tubing is inserted into the receptacle on the IV bag while holding the IV bag inverted. The bag is then held upright with the IV line hanging from the bottom. The drip chamber should be filled half-way by pinching it and releasing. Following this the bag should be hung for the IV pole, at a point above the patient, and the regulating clamp should be opened to "flush" the line of air bubbles prior to connection to the patient.

Establishing a peripheral intravenous line 1. Assemble your equipment. 2. Don a pair of appropriately sized non-latex examination gloves. 3. Apply tourniquet to the IV arm above the site. 4. Visualize and palpate the vein. 5. Cleanse the site with a chlorhexidine swab using an expanding circular motion. 6. Prepare and inspect the catheter: Remove the catheter from the package. Push down on the flashback chamber to ensure it is tight. Remove the protective cover. Inspect the catheter and needle for any damage or contaminants. Spin the hub of the catheter to ensure that it moves freely on the needle Do not move the catheter tip over the bevel of the stylet. 7. Stabilize the vein and apply countertension to the skin. 8. Insert the stylet through the skin and then reduce the angle as you advance through the vein. 9. Observe for "flash back" as blood slowly fills the flash back chamber. 10. Advance the needle approximately 1 cm further into the vein.

11. Holding the end of the catheter with your thumb and index finger, pull the needle (only) back 1 cm with your middle finger. 12. Slowly advance the catheter into the vein while keeping tension on the vein and skin. 13. Remove the tourniquet. 14. Secure the catheter by placing the Tegaderm over the lower half of the catheter hub taking care not to cover the IV tubing connection 15. Occlude the distal end of the catheter with the 3rd, 4th and 5th fingers of your non-dominant hand. 16. Secure the catheter hub with your thumb and index finger and carefully remove the needle. 17. Place the needle into the sharps container. 18. Remove the cover from the end of the IV tubing and insert the IV tubing into the hub of the catheter. 19. Secure the tubing to the catheter by screwing the Luer Lock tight. 20. Open up the IV roller clamp and observe for drips forming in the drip chamber. 21. Check that the IV is infusing into the vein by occluding the vein distal to the catheter and observing that the drips stop forming and then restart once the vein is released. 22. Adjust the IV drop to keep the vein open rate (TKVO) of approximately 30 - 60 mL/hr (one drop every 5 10 seconds for 10 gtts/mL solution set). 23. Place a piece of tape over the catheter hub. 24. Make a small (kink free) loop in the IV tubing and place a second piece of tape over the first (piece of tape) to secure the loop. 25. Place a third piece of tape over the IV tubing above the site. 26. Ensure that the IV is properly secured and infusing properly. 27. Ensure that all "sharps" are placed in the sharps container.

To remove the IV 1. Shut off the IV by closing the roller camp. 2. Remove the tape and Tegaderm from the tubing and catheter. 3. Place a non-sterile 2x2 gauze over the IV site and remove the catheter from the arm and secure it in place with a piece of tape.

Lumbar Puncture Procedural Steps

The lumbar puncture, or "LP", is a frequently performed procedure in emergency departments, neurology and radiology clinics and hospital wards. In the emergency department, LP can yield information that can rapidly differentiate benign from emergent conditions. In general, an LP may be done to:

1. 2. 3. 4.

analyse the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) measure the CSF pressure access the intrathecal space for either drainage of CSF or injection of fluid or to administer medications into the intrathecal space to perform myelography

The most common emergency department indications for a LP include clinical suspicion of meningitis (bacterial, viral or fungal) or to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage. In neurology clinics and other settings, LP is used to detect disorders with local immunoglobulin production in the CNS such as multiple sclerosis and SSPE, malignant infiltrates such as acute leukemia and lymphoma, and blockage of the spinal canal. Major contra-indications to lumbar puncture are: symptoms or signs of raised intracranial pressure. These include a decreased level of consciousness, localizing (focal) neurologic signs and papilledema. LP in patients with raised ICP may lead to uncal herniation and death, a severe bleeding diathesis or coagulation disorder or the patient is on anticoagulation therapy, infection at the planned site of the puncture

When performed correctly, the LP procedure can be rapidly completed with little discomfort or risk to the patient. Using the sterile conditions recommended in this learning module, the introduction of infection by the LP procedure itself to the spinal cord would be extremely rare. A small chance of bleeding at the site exists. However "post-LP headache" is a relatively common occurrence (in up to even greater than 30% of patients depending on the LP needle type and caliber selected - see Preparation). This headache begins usually within hours to a few days after the LP procedure and is usually made worse with a positional change to the upright posture. The headache can be very severe and although the headache usually improves over time, the headache can last up to 3 weeks. A "blood patch" may be required to seal the hole in the lumbar meninges. Bed rest (although frequently recommended), whether prone or supine, immediately after LP does not prevent the headache. A non-postural headache after an LP is uncommon. If the onset is early, consider a puncture-induced meningitis and for those headaches of later onset consider a possible subdural effusion. A signed informed consent should be obtained from the patient or a substitute decision maker after explaining the risks and benefits of the procedure. The consent form should ideally be signed by the patient in the presence of a witness. This should include a discussion of the likelihood of "post-LP headache" and the small risk of bleeding or introducing infection.

Urinary Catheter Insertion

Introduction The ability to insert a urinary catheter is an essential skill in medicine. Catheters are sized in units called French, where one French equals 1/3 of 1 mm. Catheters vary from 12 (small) FR to 48 (large) FR (3-16mm) in size.

They also come in different varieties including ones without a bladder balloon, and ones with different sized balloons - you should check how much the balloon is made to hold when inflating the balloon with water! Indications By inserting a Foley catheter, you are gaining access to the bladder and its contents. Thus enabling you to drain bladder contents, decompress the bladder, obtain a specimen, and introduce a passage into the GU tract. This will allow you to treat urinary retention, and bladder outlet obstruction. Urinary output is also a sensitive indicator of volume status and renal perfusion (and thus tissue perfusion also). In the emergency department, catheters can be used to aid in the diagnosis of GU bleeding. In some cases, as in urethral stricture or prostatic hypertrophy, insertion will be difficult and early consultation with urology is essential. Contraindications Foley catheters are contraindicated in the presence of urethral trauma. Urethral injuries may occur in patients with multisystem injuries and pelvic factures, as well as straddle impacts. If this is suspected, one must perform a genital and rectal exam first. If one finds blood at the meatus of the urethra, a scrotal hematoma, a pelvic fracture, or a high riding prostate then a high suspicion of urethral tear is present. One must then perform retrograde urethrography (injecting 20 cc of contrast into the urethra).

Equipment Sterile gloves - consider Universal Precautions Sterile drapes Cleansing solution e.g. Savlon Cotton swabs Forceps Sterile water (usually 10 cc) Foley catheter (usually 16-18 French) Syringe (usually 10 cc) Lubricant (water based jelly or xylocaine jelly) Collection bag and tubing

Procedure 1. Gather equipment. 2. Explain procedure to the patient 3. Assist patient into supine position with legs spread and feet together 4. Open catheterization kit and catheter 5. Prepare sterile field, apply sterile gloves 6. Check balloon for patency. 7. Generously coat the distal portion (2-5 cm) of the catheter with lubricant 8. Apply sterile drape

9. If female, separate labia using non-dominant hand. If male, hold the penis with the non-dominant hand. Maintain hand position until preparing to inflate balloon. 10. Using dominant hand to handle forceps, cleanse peri-urethral mucosa with cleansing solution. Cleanse anterior to posterior, inner to outer, one swipe per swab, discard swab away from sterile field.

11. Pick up catheter with gloved (and still sterile) dominant hand. Hold end of catheter loosely coiled in palm of dominant hand. 12. In the male, lift the penis to a position perpendicular to patient's body and apply light upward traction (with non-dominant hand) 13. Identify the urinary meatus and gently insert until 1 to 2 inches beyond where urine is noted 14. Inflate balloon, using correct amount of sterile liquid (usually 10 cc but check actual balloon size) 15. Gently pull catheter until inflation balloon is snug against bladder neck 16. Connect catheter to drainage system 17. Secure catheter to abdomen or thigh, without tension on tubing 18. Place drainage bag below level of bladder 19. Evaluate catheter function and amount, color, odor, and quality of urine 20. Remove gloves, dispose of equipment appropriately, wash hands 21. Document size of catheter inserted, amount of water in balloon, patient's response to procedure, and assessment of urine

Complications The main complications are tissue trauma and infection. After 48 hours of catheterization, most catheters are colonized with bacteria, thus leading to possible bacteruria and its complications. Catheters can also cause renal inflammation, nephro-cysto-lithiasis, and pyelonephritis if left in for prolonged periods. The most common short term complications are inability to insert catheter, and causation of tissue trauma during the insertion. The alternatives to urethral catheterization include suprapubic catheterization and external condom catheters for longer durations.

Understanding ER Procedures

Understanding Emergency Department Procedures Anderson Regional Medical Centers critical care patients are ALWAYS top priority, no matter who has been waiting longer in the Emergency Department. Average Visit Time The average Anderson Regional Medical Center visit for a non-critical condition is 3 to 4 hours from time of arrival to time of discharge. This is an average events in the emergency room are unpredictable and can lead to longer wait times. Triage Triage is a French word meaning to sort out. The triage nurse will determine whether you have a critical or non-critical condition, and will assign a Triage Level. Patients are seen based on the Triage Level, NOT in the order in which they arrive. Assessment Your Anderson Medical Team will focus on your presenting problem, as well as look at your medical history and conduct a physical examination. You may be asked the same questions several times, but all information is vital to improving your health. X-Rays & Lab Studies If your condition warrants it, various imaging studies may be ordered and blood, urine and other samples may be taken for testing. Imaging studies may be as simple as an X-ray, or something as involved as a CAT scan. Blood is sometimes obtained when a nurse starts an IV line or is sometimes drawn by itself. Imaging studies and tests of body fluids can take some time, so please be patient as your Anderson Medical Team awaits results. Intervention Your Anderson Medical Team may have to do things to try and improve your health or repair your injury or treat your pain. This may start as soon as your triage assessment or may need to wait until some or all of the X-ray or laboratory studies are completed. It is common for you to undergo repeated assessments after an intervention to determine if it has been beneficial. Diagnosis Diagnosis is a term to describe your medical condition. The Anderson Medical Team ALL work towards making a diagnosis of your medical condition, however in the Anderson Emergency Room, our primary mission is to make sure you do not have an injury or illness that is an immediate threat to your life or could result in a major disability to you. All of our tests are geared towards this primary mission. Many medical conditions require more extensive tests than are used in the emergency setting or require repeated evaluations over an extended period of time to make an accurate diagnosis. This is why we will refer you to see your family doctor, or, if you do not have one, recommend a staff physician. Admission If your illness or injury is severe enough, you will be admitted to the hospital. Your physician will discuss this option with you, and, if you like, your family. The Anderson ER doctor will contact your doctor to make arrangements for you to be admitted into the hospital. Other members of the Anderson Medical Team will make arrangements for a room and continued treatment. Discharge If your condition can be treated without admission to the hospital, you will be provided with the necessary information and prescriptions to allow you to safely go home.

Northern Luzon Adventist College Artacho, Sison Pangasinan

EMERGENCY ROOM PROCEDURES

Diane Kate E. Tobias

You might also like

- Nasogastric Tube InsertionDocument8 pagesNasogastric Tube InsertionMayaPopbozhikovaNo ratings yet

- NGT Feeding: by Group 2Document25 pagesNGT Feeding: by Group 2karl montano100% (1)

- CATHETERIZATIONDocument13 pagesCATHETERIZATIONSarah Uy Caronan100% (1)

- Obtaining a Capillary Blood Sample for Glucose TestingDocument4 pagesObtaining a Capillary Blood Sample for Glucose TestingJUVIELY PREMACIONo ratings yet

- Endotracheal Tube SuctioningDocument5 pagesEndotracheal Tube SuctioningArlene DalisayNo ratings yet

- Newborn Care ChecklistDocument5 pagesNewborn Care Checklistburntashes100% (1)

- Nursing Skill Iv InsertionDocument8 pagesNursing Skill Iv InsertionSabrina TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Case Study CompiledDocument392 pagesAbdominal Case Study CompiledIshak IzharNo ratings yet

- COMPREHENSIVE NURSING ACHIEVEMENT TEST (RN): Passbooks Study GuideFrom EverandCOMPREHENSIVE NURSING ACHIEVEMENT TEST (RN): Passbooks Study GuideNo ratings yet

- SuctioningDocument6 pagesSuctioningCriselda Ultado100% (2)

- Return Demonstration Evaluation Tool For: Complete BedbathDocument9 pagesReturn Demonstration Evaluation Tool For: Complete BedbathAshley Blaise JoreNo ratings yet

- Triage and Disaster: Nur Masyeerah Abdul JalilDocument22 pagesTriage and Disaster: Nur Masyeerah Abdul JalilnavenNo ratings yet

- Tracheostomy CareDocument10 pagesTracheostomy CareSharifa Al AmerNo ratings yet

- Starting An Intravenous InfusionDocument20 pagesStarting An Intravenous InfusionDoj Deej Mendoza Gamble100% (1)

- Nursing Procedure Guide - Urinary Catheter InsertionDocument3 pagesNursing Procedure Guide - Urinary Catheter Insertionmharmukim03No ratings yet

- Vital SignDocument4 pagesVital SignGabriel JocsonNo ratings yet

- Naso Orogastric Tube Guideline For The Care of Neonate Child or Young Person RequiringDocument12 pagesNaso Orogastric Tube Guideline For The Care of Neonate Child or Young Person RequiringmeisygraniaNo ratings yet

- Feeding Via Gastric GavageDocument3 pagesFeeding Via Gastric Gavageneleh gray0% (1)

- MCN SF Chapter 18 QuizDocument4 pagesMCN SF Chapter 18 QuizKathleen AngNo ratings yet

- Catheterization:: Binal Joshi, Assistant Professor, MTINDocument58 pagesCatheterization:: Binal Joshi, Assistant Professor, MTINBinal JoshiNo ratings yet

- Ret Dem Bed Bath Hair Shampoo WUPDocument4 pagesRet Dem Bed Bath Hair Shampoo WUPCarissa De Luzuriaga-BalariaNo ratings yet

- Colostomy CareDocument13 pagesColostomy CareLord Pozak MillerNo ratings yet

- Oral Care: Marlon C. Soliman, MAN, RNDocument25 pagesOral Care: Marlon C. Soliman, MAN, RNSoliman C. MarlonNo ratings yet

- Measuring Body TemperatureDocument5 pagesMeasuring Body TemperatureJan Jamison ZuluetaNo ratings yet

- Nasogastric Tube (NGT) InsertionDocument19 pagesNasogastric Tube (NGT) InsertionNorman VerdeflorNo ratings yet

- ) Administering Nasogastric Tube or Orogastric Tube FeedingDocument6 pages) Administering Nasogastric Tube or Orogastric Tube FeedingJohn Pearl FernandezNo ratings yet

- Tracheostomy CareDocument1 pageTracheostomy CareShreyas WalvekarNo ratings yet

- Thoracic and Lung Assessment: Physical Examination of The Thorax and The LungsDocument16 pagesThoracic and Lung Assessment: Physical Examination of The Thorax and The Lungsshannon c. lewis100% (1)

- Skill Performance Evaluation - Measuring Intake and OutputDocument2 pagesSkill Performance Evaluation - Measuring Intake and OutputLemuel Que100% (1)

- Nasogastric Tube Feeding GuideDocument74 pagesNasogastric Tube Feeding GuideGoddy Manzano100% (1)

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandDisseminated Intravascular Coagulation, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Pleural Tapping GuideDocument15 pagesPleural Tapping GuideAnusha Verghese100% (1)

- Blood Transfusion GuideDocument10 pagesBlood Transfusion GuideMitch SierrasNo ratings yet

- Assessing Newborns EffectivelyDocument35 pagesAssessing Newborns EffectivelyBaldwin Hamzcorp Hamoonga100% (1)

- RBS and FBSDocument5 pagesRBS and FBSAllenne Rose Labja Vale100% (1)

- NGT FeedingDocument2 pagesNGT FeedingJD Escario100% (1)

- Initiating A Blood TransfusionDocument5 pagesInitiating A Blood TransfusionJoyce Kathreen Ebio LopezNo ratings yet

- EENT Instillation and IrrigationDocument13 pagesEENT Instillation and Irrigationplebur100% (1)

- Peg TubeDocument14 pagesPeg Tubejonisyang100% (1)

- NebulizationDocument8 pagesNebulizationbajaocNo ratings yet

- Assisting With Lumbar PunctureDocument4 pagesAssisting With Lumbar PuncturePhelanCoy100% (1)

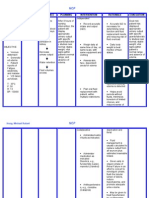

- Lab Clin Clin Tasks Attempted 1 2 3 4 5 6 7: ST ND RD TH TH TH THDocument4 pagesLab Clin Clin Tasks Attempted 1 2 3 4 5 6 7: ST ND RD TH TH TH THRichard Patterson100% (1)

- Tracheostomy Suctioning SkillDocument6 pagesTracheostomy Suctioning Skill3thanKimNo ratings yet

- Nursing Skills ChecklistDocument6 pagesNursing Skills Checklistapi-433883631No ratings yet

- Administering A Tube Feeding Preparation 1. Assess:: University of Eastern PhilippinesDocument4 pagesAdministering A Tube Feeding Preparation 1. Assess:: University of Eastern PhilippinesJerika Shane MañosoNo ratings yet

- Leopold'S Maneuver: DefinitionDocument3 pagesLeopold'S Maneuver: DefinitionJyra Mae TaganasNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Nursing ProcessDocument14 pagesModule 4 Nursing ProcessArjay Cuh-ingNo ratings yet

- First Semester 2020-2021 Study Guide: University of The CordillerasDocument13 pagesFirst Semester 2020-2021 Study Guide: University of The CordillerasJonalyn EtongNo ratings yet

- IV TherapyDocument15 pagesIV TherapyJojebelle Kate Iyog-cabanlet100% (1)

- How to Assist with Bedpans and UrinalsDocument8 pagesHow to Assist with Bedpans and UrinalsShereen AlobinayNo ratings yet

- Administering Enema POWERPOINT GIVING ENEMA TO PATIENT, FOR PATIENT WITH GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS .. LECTURES, PRINCIPLES AND PROCEDURESDocument14 pagesAdministering Enema POWERPOINT GIVING ENEMA TO PATIENT, FOR PATIENT WITH GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS .. LECTURES, PRINCIPLES AND PROCEDURESPb0% (1)

- Colostomy CareDocument2 pagesColostomy CareMel RodolfoNo ratings yet

- Lumbar PunctureDocument6 pagesLumbar PunctureShesly Philomina100% (1)

- Gavage FedingDocument9 pagesGavage FedingGeetha ReddyNo ratings yet

- Cast CareDocument1 pageCast CareCarmelita SaltNo ratings yet

- Icu Equipments BY: Presented Bhupender Kumar MehtoDocument35 pagesIcu Equipments BY: Presented Bhupender Kumar Mehtobhupendermehto012No ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandAcute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- 10-Iv line-ARLIXDocument6 pages10-Iv line-ARLIXarlixNo ratings yet

- Nasogastric Tube InsertionDocument3 pagesNasogastric Tube InsertionLorenza VillarinoNo ratings yet

- Multiple MyelomaDocument5 pagesMultiple MyelomaDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Managing Fluid Volume for Renal FailureDocument2 pagesManaging Fluid Volume for Renal FailureMark Angelo Chan100% (13)

- LactuloseDocument2 pagesLactuloseDiane Kate Tobias Magno100% (1)

- Multiple Myeloma2Document9 pagesMultiple Myeloma2Diane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Glenda S. Bermudez: Carreer ObjectivesDocument2 pagesGlenda S. Bermudez: Carreer ObjectivesDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- NCP For CVADocument18 pagesNCP For CVAmolukas101100% (6)

- Anatomy and Physiology Related To Multiple Myelom1Document15 pagesAnatomy and Physiology Related To Multiple Myelom1Diane Kate Tobias Magno100% (1)

- Diane Kate E. Tobias: Use of Over-the-Counter Cough and Cold Medications in Children Younger Than 2 YearsDocument3 pagesDiane Kate E. Tobias: Use of Over-the-Counter Cough and Cold Medications in Children Younger Than 2 YearsDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Chronic Kidney Disease 2Document83 pagesChronic Kidney Disease 2Diane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Multiple MyelomaDocument5 pagesMultiple MyelomaDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- CVA Case StudyDocument20 pagesCVA Case Studybetchai18100% (5)

- Anatomy and Physiology Related To Multiple Myelom1Document15 pagesAnatomy and Physiology Related To Multiple Myelom1Diane Kate Tobias Magno100% (1)

- Multiple MyelomaDocument46 pagesMultiple MyelomaDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Multiple Myeloma2Document9 pagesMultiple Myeloma2Diane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Diane EeeDocument3 pagesDiane EeeDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- CKD NCPDocument3 pagesCKD NCPjosanne938No ratings yet

- Terms chronic bronchitis Hemoptysis definitionsDocument5 pagesTerms chronic bronchitis Hemoptysis definitionsDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Benevoence 2Document7 pagesBenevoence 2Diane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Newstart 2Document5 pagesNewstart 2Diane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- What Is Constipation?: Diarrhea Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocument51 pagesWhat Is Constipation?: Diarrhea Irritable Bowel SyndromeDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- ICU-Acquired Pneumonia Outcomes With or Without DiagnosisDocument4 pagesICU-Acquired Pneumonia Outcomes With or Without DiagnosisDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Thesis Research 1Document27 pagesThesis Research 1Diane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Salivary DiseasesDocument43 pagesSalivary DiseasesDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Non-Pharmaceutical Therapy For Hypertension: LifestyleDocument1 pageNon-Pharmaceutical Therapy For Hypertension: LifestyleDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Induced HypertensionDocument3 pagesPregnancy Induced HypertensionDiane Kate Tobias Magno100% (1)

- Pregnancy Induced HypertensionDocument3 pagesPregnancy Induced HypertensionDiane Kate Tobias Magno100% (1)

- Activityintolerancerelated Tomuscle OrcellularhypersensitivityDocument3 pagesActivityintolerancerelated Tomuscle OrcellularhypersensitivityDiane Kate Tobias MagnoNo ratings yet

- Marriage and Later PartDocument25 pagesMarriage and Later PartDeepak PoudelNo ratings yet

- Template Clerking PsychiatryDocument2 pagesTemplate Clerking Psychiatrymunii28No ratings yet

- Nps Docket No. Ix Inv 21h 00387 ScribdDocument4 pagesNps Docket No. Ix Inv 21h 00387 ScribdGrethel H SobrepeñaNo ratings yet

- Cwu 1 OrthoDocument14 pagesCwu 1 OrthoHakimah K. Suhaimi100% (1)

- Nursing Acn-IiDocument80 pagesNursing Acn-IiMunawar100% (6)

- The Holy Grail of Curing DPDRDocument12 pagesThe Holy Grail of Curing DPDRDany Mojica100% (1)

- Sop Cleaning Rev 06 - 2018 Rev Baru (Repaired)Document20 pagesSop Cleaning Rev 06 - 2018 Rev Baru (Repaired)FajarRachmadiNo ratings yet

- Assessmen Ttool - Student AssessmentDocument5 pagesAssessmen Ttool - Student AssessmentsachiNo ratings yet

- List of 220KV Grid Stations-NTDCDocument7 pagesList of 220KV Grid Stations-NTDCImad Ullah0% (1)

- The Body and Body Products As Transitional Objects and PhenomenaDocument12 pagesThe Body and Body Products As Transitional Objects and PhenomenaOctavian CiuchesNo ratings yet

- Lateral SMASectomy FaceliftDocument8 pagesLateral SMASectomy FaceliftLê Minh KhôiNo ratings yet

- 9 Facebook BmiDocument29 pages9 Facebook BmiDin Flores MacawiliNo ratings yet

- Surgical Instruments and Drains PDFDocument117 pagesSurgical Instruments and Drains PDFNariska CooperNo ratings yet

- 2) Water Quality and Health in Egypt - Dr. AmalDocument50 pages2) Water Quality and Health in Egypt - Dr. AmalAlirio Alonso CNo ratings yet

- REAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Penatalaksanaan Pasien Rheumatoid Arthritis Berbasis Evidence Based Nursing: Studi KasusDocument7 pagesREAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Penatalaksanaan Pasien Rheumatoid Arthritis Berbasis Evidence Based Nursing: Studi Kasustia suhadaNo ratings yet

- Appointments Boards and Commissions 09-01-15Document23 pagesAppointments Boards and Commissions 09-01-15L. A. PatersonNo ratings yet

- Al Shehri 2008Document10 pagesAl Shehri 2008Dewi MaryamNo ratings yet

- The Cause of TeenageDocument18 pagesThe Cause of TeenageApril Flores PobocanNo ratings yet

- Emergent Care Clinic StudyDocument5 pagesEmergent Care Clinic StudyAna Bienne0% (1)

- Metaphor and MedicineDocument9 pagesMetaphor and MedicineCrystal DuarteNo ratings yet

- Hahnemann Advance MethodDocument2 pagesHahnemann Advance MethodRehan AnisNo ratings yet

- Drug in PregnancyDocument5 pagesDrug in PregnancyjokosudibyoNo ratings yet

- "We Are Their Slaves" by Gregory FlanneryDocument4 pages"We Are Their Slaves" by Gregory FlanneryAndy100% (2)

- Which Is More Effective in Treating Chronic Stable Angina, Trimetazidine or Diltiazem?Document5 pagesWhich Is More Effective in Treating Chronic Stable Angina, Trimetazidine or Diltiazem?Lemuel Glenn BautistaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Banis' Psychosomatic Energetics Method for Healing Health ConditionsDocument34 pagesDr. Banis' Psychosomatic Energetics Method for Healing Health ConditionsmhadarNo ratings yet

- Kasaj2018 Definition of Gingival Recession and Anaromical ConsiderationsDocument10 pagesKasaj2018 Definition of Gingival Recession and Anaromical ConsiderationsAna Maria Montoya GomezNo ratings yet

- OGL 481 Pro-Seminar I: PCA-Ethical Communities Worksheet Erica KovarikDocument4 pagesOGL 481 Pro-Seminar I: PCA-Ethical Communities Worksheet Erica Kovarikapi-529016443No ratings yet

- Agile Project Management: Course 4. Agile Leadership Principles and Practices Module 3 of 4Document32 pagesAgile Project Management: Course 4. Agile Leadership Principles and Practices Module 3 of 4John BenderNo ratings yet

- Marijuana Recalled Due To PesticidesDocument4 pagesMarijuana Recalled Due To PesticidesAllison SylteNo ratings yet

- 09022016att ComplaintDocument25 pages09022016att Complaintsarah_larimerNo ratings yet