Professional Documents

Culture Documents

For Cim 3000 Words

Uploaded by

Vivi Sabrina BaswedanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

For Cim 3000 Words

Uploaded by

Vivi Sabrina BaswedanCopyright:

Available Formats

INTRODUCTION British American Tobacco London, UK products Gross Turnover: 26,234 million (2007) Revenue: 10,018 million (2007)

07) Employees: 53,907 (2008) Website: www.bat.com (SAP A6, 2009)

In 2011 the company supplied around 180 markets with 705 billion cigarettes. These were produced at 46 factories in 39 countries. British American Tobacco is the only tobacco business with a significant interest in tobacco growing, providing agronomy support to around 70 per cent of the farmers we purchase leaf from. The company also invests heavily in research and development, which involves not only product innovations, but also research into potentially reducedrisk products. (British American Tobacco, 2012)

four leading brands are Dunhill, Kent, lucky strike and pall mall. We call them our Global Drive Brands. We have many other leading international and local brands, including Vogue, Viceroy, Kool, Rothmans, peter stuyvesant, Benson & hedges and state express 555. (British American Tobacco, 2012)

Leading our industry our vision is to achieve leadership of the global tobacco industry, not just in volume and value, but also in the quality of our business. To be industry leaders we must continue to demonstrate that we are a responsible tobacco Group with outstanding people, brands and products. our consistent strategy is based on growth, funded by productivity, and delivered by a winning organisation that acts responsibly at all times. our balanced strategy adds value at every stage of our operations, including working directly with tobacco farmers, having our own manufacturing capabilities and investing in research and development. (British American Tobacco, 2012)

TABLE XX ABOUT BAT PER REGION Region Volume Revenue Employees Share of Group Revenue Americas 143 3,558 m 3,600 m 4,251 m 3,990 m 16,661 12,138 15,351 12,115 23% 23% 28% 26%

Western Europe 135 Asia-Pasific 191

Eastern Europe, 236 Middle East, & Africa

(British American Tobacco, 2012)

The tobacco industry is one of the most profitable and deadly industries in the world. The global cigarette business alone is valued at $559.9 billion USD. (Gobal Tobacco, 2010)

BAT is the second most profitable publicly traded tobacco company in the world behind PMI. It is currently valued at $80 billion USD.4 In 2009, BAT generated 2.9 billion ($4.8 billion USD) in profits after taxes.5 The company reported 907 billion sticks in cigarette volume sold worldwide, down by 1% from 2008.5 According to tobacco market analysts at Euromonitor International, BAT held a 12.7% retail volume market share in cigarettes worldwide in 2009 and a 20.7% volume share of the global market (excluding China).6 (Gobal Tobacco, 2010) In 2009, BATs best performing region was the Africa and Middle East region. BAT reported 724 million ($1.17 billion USD) in operational profits, a 41% increase from 2008. Cigarette volume in the region increased by 11% to 127 billion sticks in 2009.5 The Asia-Pacific region was BATs largest region by volume in 2009, which

increased by 3% to 185 billion cigarettes. Profits from the Asia-Pacific region increased 24% for an operational profit of 1.15 billion* ($1.85 billion USD). In 2009, 26% of BATs total volume was sold in the Asia-Pacific region.5

(Gobal Tobacco, 2010)

TABLE XX GLOBAL CIGARETTE MARKET SHARE 2007 Company China National Tobacco Corporation Philip Morris International British American Tobacco Others Japan Tobacco International Imperial Tobacco/Altadis Market Share 32.0% 18.7% 17.1% 15.8% 10.8% 5.6%

(Afro.Who.Int, 2007)

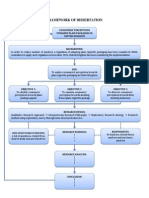

This report aims to analyse and evaluate British American Tobacco with resect to how the companys managing strategic change, affect its performance, and how the companys mergers and acquisitions (M&A), affect its performance, particularly in the context of financial aspect. First, the report will review all related literature in regards to managing strategic change and M&As. It will identify the concept of strategic change, then focus on identifying five change levers. It will also identify what manager or top managers should do to manage strategic change. The report will cover any literature about mergers and acquisitons as well as motivations behind M&A in relation to financial aspect. The next step, this report will describe the findings about British American Tobaco in the extent of strategic change and M&A, analyse those findings using provided theories, and eventually, will evaluate the findings in the context of financial aspect. In the end, as part of the whole structure of this report, it will conclude and furthermore

deliver possible recommendation if any.

LITERATURE REVIEW Change is a major issue, affecting all organizations, groups and individuals. There are numerous sources of change, and extensive guidance on how to manage change. Yet change remains a difficult area for those managing it and those affected by it. (Staniforth, 1996). When discuss about managing strategic change, it is important to have the framework or what construct an organization to change. Table xx below illustrates the key elements in managing strategic change

when analysing organizational change, it is useful to consider the spiral effect of levers for change. One lever for change may affect another, or one organizational response may prompt other changes. Accordingly, understanding the levers for change requires simplification of a process which in reality is complex and dynamic. (Staniforthh, 1996) There is variety of change levers that change agents or managers may choose as well as be aware of while working to implement changes (Howes and Quinn, 1978). According to Johnson et al (2008), five common change levers include: Strategic Change, which focus on changing direction, sped, magnitude, and pace. Administration Change means changing all formal and informal structure and reporting systems. Operational Change by changing all formal operational network and transaction systems. Cultural Change, which focus on changing all routines, rituals, stories, and symbols. Interpersonal Change by changing communications, training, and management development.

There are numerous sources of change, and extensive guidance on how to manage change. Yet change remains a difficult area for those managing it and those affected by it.

According to Theory and research on strategic decision-making have increasingly suggested that strategic choices are influenced by the personal background and prior experience of top managers. (Westphal, and Fredrickson, 2001). Managers typically decide what organizational changes should be made, and the ways in which these should be implemented. Different values, expectations, roles or strate- gies are likely to give rise to different perceptions on change, but most changes are goal oriented with the common corporate goals being survival, growth and profitability. (Staniforth, 1996) Often change is only made possible by the introduction of a new manager, frequently an outsider, and many have commented on the benefits that `new blood' can bring to a company (e.g. Sathe, 1989; Gabarro, 1987; Allcorn, 1990). New managers have not been indoctrinated by the values and norms of the organization, and their different experiences can allow existing problems to be viewed in new ways (Rieple, 1997) a basic tenet of research on strategic change is that new top managers, and especially managers recruited from outside the organization, typically initiate change and determine the new strategic direction for their firm (Miles et al., 1978; Grimm and Smith, 1991; Tushman and Romanelli, 1985) (Westphal and Fredrickson, 2001) In a recent study, Boeker (1997a) provided strong evidence that when firms recruit a new CEO from outside the organization, they tend to initiate strategic changes that lead the firm to resemble the CEOs prior employer (see also Child and Smith, 1987; Kraatz and Moore, 1998; Sambharya, 1996). Moreover, several stud- ies suggest that the board appointments held by top executives in other firms appear to influence major strategic decisions in the executives own firm. (Westphal and Fredrickson 2001) A new chief executive from outside the company indicates that a change of strategy of whatever nature, is likely to follow, often as the result of poor organizational performance prior to the change (Hofer 1982; Guthrie and Olian 1991). However, although the correlation between change of chief executive and strategy is comparatively well documented (for example Wiersema and Bantel 1992), fewer studies have looked at the mechanisms whereby particular attributes subsequently influence the implementation

of strategy, particularly where this is new to the organisation. At this time, the organization is likely to be in a state of considerable uncertainty identified in many of the company life-cycle models (for example Johnson 1992). Under these circumstances the required attributes of managers may be very different from those in companies which are in a state of strategic stability. Changing staff may have the effect of reinforcing the organisations new ideology through the selection of personnel who will support the new direction, In addition the use of individuals who had been supporters of the old regimes and have converted become powerful symbols of change. Those who do not subscribe to the new ways must be removed or omitted from the decision-making processes (Johnson 1984) (Rieple, 1995) Within the context of organizational change, research has demonstrated that uncertainty is often a major consequence for employees (Ashford, 1988; Schweiger and Denisi, 1991). During organizational change, employees are likely to experience uncertainty in relation to a range of different organizational issues, including the rationale behind the change, the process of implementation, and the expected outcomes of the change (Jackson et al., 1987; Buono and Bowditch, 1989). Research has also indicated that employees may experience uncertainty regarding the security of their position, and their future roles and responsibilities (Bordia et al., 2004a). Consequently, organizational change is a major stressor during which employees seek to gain some prediction and under- standing over events in order to minimize their uncertainty (Sutton and Kahn, 1986). Thus, it is the degree to which these specific informational needs are addressed through communication during organizational change that is worthy of deeper investigation. (Allen et al, 2007) It has long been recognized that effective and appropriate communication is a vital ingredient in the success of change programmes (Lewin, 1951; Goodstein and Warner-Burke, 1991; Kotter, 1996). In particular, at the individual level, appropriate communication has been identified as a significant factor in helping employees understand both the need for change, and the personal effects of the proposed change.

These have been regarded as especially important prerequisites for achieving change programme objectives, as they may help induce "readiness for change' at a personal level (Armenakis and Harris, 2002: Balogun and Hope- Hailey, 2003). In addition, communication can be used to reduce resistance, minimize uncertainty, and gain involvement and commitment as the change (Goodman and Truss, 2004) progresses which may, in turn, improve morale and retention rates {Klein. 1996). At the organizational level, communication has been found to play an important role in enabling change managers to challenge embedded cultural and structural norms (Deal and Kennedy. 1982; Lok and Crawford, 1999; Pinnington and Edwards, 2000). Conversely, it has also been shown that ineffective internal communication is a major contributor to the failure of change initiatives (Coulson- Thomas, 1997). (Goodman and Truss, 2004) The four types of management control systems are: Beliefs systems: formal systems used by top managers to define, communicate, and reinforce the basic values, purpose, and direction for the organization. Beliefs systems are created and communicated through formal documents such as credos, mission statements, and statements of purpose. Analysis of core values infiuences the design of beliefs systems. Boundary systems: formal systems used by top managers to establish explicit limits and rules which must be respected. Boundary systems are stated typically in negative terms or as minimum standards. Boundary systems are created through codes of business conduct, strategic planning systems, and operating directives provided to business managers. Analysis of risks lo be avoided infiuences the design of boundary systems. Diagnostic Control systems: Formal feedback systems used to monitor organizational outcomes ad correct deviations from preset standards of performance Interactive control systems: formal systems used by top managers to regularly and personally involve themselves in the decision activities of subordinates. Any diagnostic control system can be made interactive by continuing and frequent top management attention and interest. (Simons, 1994)

In todays globalized economy, Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) are being increasingly used the world over for improving the competitiveness of companies through gaining greater market share, broadening the portfolio to reduce business risk for entering new markets and geographies, capitalizing on economies of scale, etc. (Shukla and Gekara, 2010) Mergers and acquisition have become attractive options in the last years in emerging markets being driven not only by a financial attractiveness point of view but also seen as a strategic investment movement (Anagnoste and Dumitru, 2011) The growing tendency towards mergers and acquisitions (M&As) worldwide, has been driven by intensifying competition. There is a need to reduce costs, reach global size, take benefit of economies of scale, increase investment in technology for strategic gains, desire to expand business into new areas and improve shareholder value. (Sinha et al, 2010) Mergers and acquisitions are crucial to the growth and health of an economy being a highly attractive means for business owners and entrepreneurs to get value from the wealth they have contributed in creating. Mergers are vital tools used by companies for the purpose of expanding their business operations with objectives ranging from increasing their size, long term profitability or relevance within a particular market. (Ajogwu, 2011) Companies never stop searching for sources of profitable growth, whether organic (hiring additional salespeople, developing new products) or inorganic (firm acquisition). Traditionally, scholars have recognized that there are two types of firm growth strategies: internal (organic) and external (M&A) (Dickerson et al., 1997). Internal growth (organic growth) means that firm growth is realized through the firm's own strengths and resources. Internal growth usually requires a long time because sudden jumps in the internal growth process are difficult to achieve. On the other hand, external growth (growth through M&A) signifies a strategy that is achieved by buying another firm or

business. External growth is usually perceived as a faster strategy than internal growth ( [Ikeda and Doi, 1983], [Scherer and Ross, 1990] and [Trautwein, 1990]). M&A can provide a stimulus to growth, enable market dominance in a slow growth market, enlarge geographical/product/domain footprint or also provide opportunities for enhancing the bottom line through better synergies and reduced overheads. The drivers of mergers and acquisitions can be very different depending upon the industry and firm specific factors; however, growth is the dominant driver of M&A (Anagnoste and Dumitru, 2011) Merger waves often take place during periods of structural change in a particular industry, or during times of general economic disturbance (Linn and Zhu 1997; Resende 1999). For example, if an industry is becoming more consolidated, it may become harder for smaller firms to remain competitive If a firm begins to employ this strategy, other firms may begin to consolidate to remain competitive (Jensen 1986). Therefore, the merger and acquisition activity of one firm may influence the merger and acquisition activities of competing firms.(Wolfe et al, 2011) Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) have thus become universal tools to attain greater market share, acquire additional brands, cannibalize competing brands, realize improved infrastructure, create new synergies, capitalize on efficiencies and economies of scale, globalize in shorter spans of time (Shukla and Gekara, 2010) Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activities rose to a global record of US$3.8Trillion in 2006. This marked an increase of over thirty-five percent from year 2005, and surpassed the previous high of US$3.4Trillion set in year 2000 during the previous M&A boom.4 Many of these transactions were cross-border. In a study conducted in 2000 by Lehman Brothers and another in 2010 by Morgan Stanley, it was found that, on average, large M&A deals cause the domestic currency of the target corporation to appreciate by one percent relative to the acquirer's (Ajogwu, 2011) Worldwide M&A activity takes place on a major scale but tends to go in waves. Table xx

illustrates worldwide M&A by value (Johnson et al, 2008): The phrase mergers and acquisitions (abbreviated M&A) has been referred to as the aspect of corporate strategy, corporate finance and management dealing with the buying, selling and combining of different companies that can aid, finance, or help a growing company in a given industry, grow rapidly without having to create another business entity. Although they are often uttered in the same breath and used as though they were synonymous, the terms merger and acquisition mean slightly different things.2 (Ajogwu, 2011) The terms merger and acquisition are often used interchangeably to mean the same thing, and in a more common sense used in the twin form of mergers and acquisitions. Acquisition describes the act of gaining effective control over the assets or management and ownership (of shares in the capital) of another company without any combination of companies. Whereas in the case of acquisitions, the companies remain separate legal entities; but with some change in control of companies, the acquisition is seen as a takeover of the target. In this regard, the term acquisition can be interchanged with takeover. (Ajogwu, 2011) Traditionally, mergers and acquisitions (M&As) have been defined to be the purchase of entire companies or specific assets by another company. In more general terms, this implies tbat a new combination of existing assets is formed, Neoclassical economic theory predicts that the new cotnbination will be more productive than the sum of its parts; bence, synergy gains will be realized, (Ahern and Weston, 2007) When one company (the acquirer) procures another company (the target), it is called acquisition. It is also termed as buying out or taking over a company. However, the two companies do not lose their original identities and it is a voluntary combination of the two firms and not a hostile take over (Karim et al, 2011) Regardless of the fact that both terms are used in the same sense, however, there exists difference between both the terminologies. In case of acquisition, the acquirer takes charge over the company and is considered as the new owner of the company.

Acquisition leads the acquired company to lose its existence i.e. the acquirer swallows the target and continues to trade its stocks in its own name. On the contrary mergers take place when two, similar in size, voluntarily join hands and cooperate with each other in operating a new style of the company. In this case, the companies give up their stocks and initiate the new merger by the issue of fresh stocks. (Karim et al, 2011) THE PROCESS OF M&A (APPENDIX) (Connell, 2011) There are different motives for developing through M&A. A major reason can be the need to keep up with a changing environment: Speed of entry: Rapid changing of product, thus M&A becomes the only way of successfully entering the market The competitive situation may influence a company to prefer acquisition. Consolidation opportunities. M&A can improve the balance of supply and demand in a low-level industry competition. Financial markets may provide conditions that motivate M&A

Motivations for mergers and acquisitions are typically classified along the following lines: synergy, taxes, bargains, hubris, macroeconomic factors, and merger waves. The concept of synergy suggests that by joining two companies, the value of the resulting company is greater than the sum of the two companies individually. Another driving force for mergers and acquisitions is the desire to take advantage of a firm that is undervalued or a bargain on the market (Wolfe et al, 2011) The business rationale for mergers is that they can be positive net present value investments. Mergers increase value when the value of the combined firm is greater than the sum of the pre-merger values of the independent entities. One of the advantages of combining firms is that capabilities can be added more quickly than by internal programs.

With greater turbulence in the economic environment, the pressures to adjust to change rapidly are increased. Mergers enable a firm to adapt to change more rapidly than internal organic growth. Hence, more rap- idly changing environments create a greater potential role for M&As. (Ahern and Weston, 2007) Mergers can reduce industry competition and so result in higher prices for consumers. But on the other hand, mergers may give rise to efficiency gains (economies of scale) that reduce the cost of production or distribution. (Perry and Porter, 1985) Firms which do not participate in a merger may benefit less more than the participants (Perry and Porter, 1985) Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) offer various advantages such as the immediate access to technologies, products, distribution channels, and favourable market positions. It seems that the desire to obtain valuable resources has been one of the major drivers in the most recent wave of acquisition activity ( [Chaudhuri and Tabrizi, 1999] and [Heeley et al., 2006]). More specifically, M&As are a strategy for overcoming a lack of knowledge, reducing R&D costs and increasing the number of potential products in a pipeline ( [Ahuja and Katila, 2001] and [Ranft and Lord, 2002]). Several contributions have therefore emphasized the important role that M&As can play as an external source of innovation ( [Arora and Gambardella, 1990], [Graebner, 2004] and [Hitt et al., 1996]). (Al-Laham et al, 2009) According to Hay and Liu (1998), faster growth may occur even after an M&A because firms executing M&A experience lower costs due to their larger size. These lower costs put the firms in a better price position, and consequently the firms have more growth potential. (Park and Jang, 2011) Yet, the management and the integration of such acquisitions pose significant problems. Acquisitions can lead to high levels of stress (Cartwright & Cooper, 1992), increased

turnover (Hambrick & Canella, 1993), and a drop in the productivity of acquired R&D personnel (Paruchuri, Nerkar, & Hambrick, 2006), which will hinder the successful realization of innovations following an acquisition. In fact, there is considerable evidence that many M&As have failed to achieve their objectives due to difficulties in the postacquisition integration process ( [Datta et al., 1992], [Marks and Mirvis, 2001] and [Sirower, 1997]). (A-Laham et al, 2009)

post-M&A integration is a difficult process. Post-M&A integration is a time-consuming process and the real chemical integration required to achieve synergy is difficult to accomplish (David and Singh, 1994). Besides, it also takes time to restructure the acquired firm. Some sectors of the business might overlap with an acquired firm and, occasionally, some sectors may not be exactly what the acquirer wanted. (Park and Jang, 2011). companies should pursue an identical type of generic business strategy within the same industry in the post acquisition period in order to realise the most important synergies (Lahovnic, 2011)

Existing integration approaches and typologies ( [Buono and Bowditch, 1989], [Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991] and [Marks and Mirvis, 1998]) sometimes fail to address the complexity of the post-acquisition integration process as they tend to offer a solution in which a given kind of combination leads to exactly one integration approach. However, in view of the high failure rate of M&As we see a need to go beyond these general approaches (Schweizer, 2005). Puranam et al. (2006) suggest that acquirers can resolve the coordination-autonomy dilemma by recognizing that the effect of organization on innovation outcomes depends on the developmental stage of the acquired firm's innovation trajectories. Given the difficulty to determine the appropriate postacquisition integration approach, it should be tricky for the acquirer to exactly determine the developmental stage of the acquired firm's innovation trajectory right after the acquisition. (Al-Laham et al, 2009)

HOWEVER,, In terms of the effect of M&A on firm growth, several studies found that M&A had a negative influence on firm growth. Cosh et al. (1989), Mueller (1985), and Kumar (1985) used the event study method and suggested that M&A had a significant negative impact on firm growth. Odagiri and Hase (1989) also concluded that M&A did not improve the growth rate three years after M&A. However, two studies examining the M&A of Japanese companies ( [Hoshino, 1982] and [Taketoshi, 1984]) reported positive growths after M&A. Consequently, except for the two studies of Japanese companies, most prior studies have claimed that M&A has a negative effect on firm growth (Park and Jang, 2011)

HOWEVER, As many as 70% of acquisitions end up with lower returns to shareholders or both organisations. The most common mistake is in paying too much for a company or managers of the acquiring company may be over optimistic about the benefits of the M&A. M&A might not provide exactly what firms would prefer because they are purchasing an already existing business or company. Consequently, this could actually lead to a reduction in firm performance. Also, there may be difficulties in integrating the acquired firm into the acquiring firm. Thus, costs are incurred in association with M&A, and these costs can sometimes dominate the benefits of M&A. One major cost is related to cultural differences between the acquiring and acquired businesses (David and Singh, 1994 (Park and Jang, 2011) Problems of cultural fit. This can arise because the there are certain part of differences between two companies and many times to be proven as a major issue in M&A. Many (for example Hassardand Sharifi 1989) have also commented on the

difficulty of achieving cultural change. When new senior executives try to make modifications, they discover strong bonds within the organization, which reject new initiatives. Thus the use of power, by means of contingent behaviours such as the ruthless removal of un-supportive staff, and the substitute of sympathisers may be an important behavior.

Many (for example, Schein, 1992) have commented on the difficulty of achieving significant organization or cultural change. A company's cultural systems and structures are intimately related to, and interdependent on, one another. When change is introduced in one element in isolation, the others are likely to act to undermine its success, a factor which appears to underlie Pettigrew and Whipp's (1992) development of the concept of `coherence' when attempting organization change. However, such a process is likely to be fraught with difficulties ((Rieple, 1997)

there are four issues in order to make M&A work (if not successfully handled, M&A will meet failure): The adding value. The acquirer may find difficulty in adding value to the acquired business. Gaining the commitment of middle managers responsible for the operations and customer relations in the acquired business is important in order to avoid uncertainties. Expected synergies may not be realized, because they do not exist to the extent expected

There is a manifest need to improve merger and acquisition (M and A) performance. Most performance improvement efforts have focused on reducing acquirers purchases of bad companies or designing approaches to avoid paying too much for good ones. Performance can also be improved by increasing the number of potentially attractive targets that are purchased at appropriate prices (Connell, 2011)

FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION BAT aims to grow its global market share by meeting the preferences of adult tobacco consumers and differentiating the companys brands from those of its competitors.

It is achieving this by turning a multinational business operating across multiple markets into an integrated global enterprise that can take full advantage of its scale. Simplifying the companys complex IT landscape is crucial to the success of this strategy, and in 2004 BAT embarked on an ambitious four-year programme to consolidate its myriad back office ERP systems onto regional SAP ERP platforms. The implications for the business are exciting. Running all of these different back office systems may have been acceptable for the business operating model we had in the past, but today this is a serious inhibitor, says Ebert Spreeth, Global Programme Manager EAS Convergence will move us to an environment that is far less costly to sustain. It will take less time to roll out new systems and to provide common information at regional and global levels. (SAP A6, 2009) STRATEGIC

British American Tobacco (BAT) estimated that it saved UK5 million by implementing "Project Darwin," (High Beam Research, 2005) STRATEGIC As part of our plans to reduce complexity, drive efficiency in management structures and achieve a better balance in the scale of the regions, the number of regions is being reduced from five to four from 1 January 2011. ADMINISTRATION (BAT Annual Report, 2011) Markets, which currently comprise the Eastern Europe region, will be merged into the Africa and Middle East region and the Western Europe region. Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Caucasus and Central Asia will form part of the new Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa region (EEMEA) while Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania and Kosovo will become part of the Western Europe region. (BAT Annual Report, 2011) ADMINISTRATION

British American Tobacco is proposing to reduce the number of Regions in its management structure from five to four with effect from 1st January 2011. As a result, a new region will be formed, Eastern Europe, Middle East & Africa (EEMEA). The Groups Asia-Pacific and Americas Regions will remain unchanged, as will the Western Europe Region (WE) apart from the inclusion of the South Eastern Europe (SEE) Area with effect from 1st January 2011 as described below. (BAT New Release, 2010) ADMINISTRATION Commenting on the proposed changes, Nicandro Durante, Chief Executive Designate, said: This is an important step in our plans to reduce complexity in our management structures and achieve a better balance in the scale of the resulting four Regions. (BAT News Release, 2010)

PA Consulting Group has helped British American Tobacco (BAT) to develop a customer service strategy supporting the overall execution of BAT's new global operating model which is designed to deliver 1billion savings. This was a unique opportunity for PA to leverage the experience for customer-driven supply and provide BAT with a clear customer service strategy for 2012. Based on designing the supply chain from the 'shelf back' BAT becomes a much more commercially focused organisation through a better understanding of the consumer needs. The strategy helps BAT to save at least 20million in service failure cost as well as helping the company to improve product's availability, reliability, value and service differentiation. It will help BAT establish a culture where people understand customer needs and where people are committed to providing an outstanding level of service. (PA Consulting Group, 2012) OPERATION

In 2001, British American Tobacco Hungary (BAT Hungary) began implementing a new direct store delivery strategy designed to improve the trade management of retail customer accounts and to ensure fewer stock-outs. This plan required significant change in the companys sales and logistics operations, including the elimination of its indirect

distribution channel and the recruitment of over 300 BAT Hungary sales and replenishment representatives. Since implementing Descartes, we have been able to improve the efficiency of our distribution operation in Hungary, adds Coutinho. By generating flexible, optimised routes for our direct store delivery operation, we are better able to respond to market changes and save on distribution costs. Today, BAT Hungary can service more retail outlets with fewer vehicles through continuous routing enhancements. Further, BAT Hungary can fine-tune its trade marketing and distribution operations by analyzing sales and delivery data derived from Descartes. (Decartes, 2011) OPERATION British American Tobacco is committed to reducing its carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions by 50 per cent (by 2030) and 80 per cent (by 2050) against its 2000 baseline of 1.38 tonnes per million cigarettes equivalent. To achieve these targets we focus on our energy use (reducing consumption and switching to less carbon intensive energy sources), waste to landfill and business travel. In 2010, despite dramatic weather patterns witnessed in the year, there was a decrease in our absolute energy consumption by 1.5 per cent driven primarily by various energy reduction programmes and site rationalisation. This also resulted in a decrease in CO2e. However, our overall energy use per million cigarettes equivalent increased due to a reduction in production volume. (BAT Stakeholder Dialogue Report, 2012) OPERATION

Our employees come from diverse cultures and backgrounds, and our business benefits from the breadth of ideas and experiences they bring. We aim to recognise individuality and encourage people to perform at their best. We are experiencing a period of organisational change as the Group becomes a more globally integrated organisation. Some changes have yet to be implemented, but we know our employees have concerns about what the future might bring and we want to support them so that they feel confident about working in new team structures as we move away from traditional business hierarchies. (BAT People, 2011) CULTURAL

BAT has transformed its supply chain division in the UK from a departmentalised operation with a silo mentality to a much flatter organisation that is driven more by customer demand (and a desire to improve customer service), and which now shares information much more readily across the supply chain enterprise. (Im@t Online, 2003) CULTURAL The division's new structure is today the opposite of what it was in 2001 and is a classic example what can be achieved by using OTI to analyse what is going in an organisation, measuring the impacts, bringing staff on board and rolling out a step-by-step programme to meet a defined desired goal, while carrying out measures as the programme proceeds, and re-measures after implementation, to ensure the change stays on course. (Im@t Online, 2003) CULTURAL The supply chain organisation produced a new vision that was shared with its employees, i.e. they participated in creating it. According to Lisa Thomas, HR Manager at BAT, a survey of the staff had found that they didn't understand the existing supply chain strategywhich was rapidly becoming out of date, says Thomas. In 2002 the division was functional and departmentalised; now it is a much flattened organisation that is based around interlinked processes. In practical terms, this means that people's reporting lines now cross boundaries, interfacing across what were the silos, or departmentsand being driven by dynamic processes rather than by job function (Im@t Online, 2003) CULTURAL

Launched quietly in 2008, Connect quickly spread over the first three weeks before an official announcement helped it become the most widely used tool on Interact. A measure of its success is that of the 26,000 registered Interact users, over 19,000 have been found to use Connect in a six-month period. Connect also enables people to contact their peers in the handful of markets which have their own additional non-

Interact intranets. All Connect users see a newsfeed on their homepage, which shows what their connections have done, whether theyve connected to other employees, posted to a blog or joined a community. This increases the users ambient awareness of the activity around them. An unexpected side effect of Connect is that more people now update their profiles. When Connect was seen as merely a directory, there was an expectation that this was someone elses job. Since it has become a networking tool, people have started to see updating their own profiles as their own responsibility. Connect has now become the de facto source of people-based information at British American Tobacco. Management information on employees is imported from the SAP (an enterprise resource planning system commonly found in most large organisations) to populate the organisational structure charts, which Connect generates on-the-fly whenever someone opens a Connect record. Work is now continuing to make Connect the visible front end to British American Tobaccos implementation of Active Directory. A more integrated future Although the KM team was cut to two people at the turn of the year, the teams vision of a joined-up organisation is becoming a reality. As the tools British American Tobacco uses to communicate and collaborate have become more integrated, the organisation itself moves in the same direction. The pressure to reduce cost and stretch existing resources increases with the consolidation of factories leading to more above-market4 working and regional collaboration.

The need to support this integrated future with simple, effective tools to connect people is now greater than ever. (Inside Knowledge, 2010) INTERPERSONAL

BAT has done several mergers and acquisitions with 2011 concludes with the US$452 million acquisition of Protabaco in Colombia (BAT History, 2011 & Harbord and Riascos, 2011) The deal is likely to contribute to solid medium-term growth in Latin America ,,,,, Five months ago, Philip Morris International (PM) withdrew from a deal to acquire Protabaco after the government raised objections on antitrust grounds. (Morningstar, 2011) On April 8, 1999, British American Tobacco acquired Rothmans International NV. The cost was $ 7.41 billion, resulted: After just four months, BAT's pretax profits for the first three quarters of 1999 were 26% higher than during the same three quarters of 1998, ales in Asia, excluding duties and taxes, increased from GBP 822 million for the first three quarters. During the same period in 1998, the figure was GBP 763 million, a 7.7% increase, Four months later, it BAT bought the 58% stake in Canada's Imasco Ltd. that it did not already own for $6.8 billion. According to some analysts, the deal reflected BAT's goal of displacing Philip Morris as the #1 tobacco power in the world. (Soc.Duke.Edu, 2000) TABLE XX BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO-ROTHMANS MARKETSHARE AFTER M&A Country Market Share Competitors Share Belgium 38.7% (BAT 11.7% & Philip Morris (39.9%) Market

Rothmans 27%) France 18.8% (BAT 2.4% & Philip Morris (30.2%)

Rothmans 16.4%) Germany 19.9% (BAT 13.1% & Philip Morris (41.9%)

Rothmans 6.8%) Greece 16.7% (BAT 2.5% & Philip Morris (23.3%)

Rothmans 14.2%)

Luxembourg

29.1%

(BAT

11.5%

& Philip Morris (28.4%)

Rothmans 17.6%) Netherlands 47% (BAT 19.3% & Philip Morris (34.4%)

Rothmans 27.7%) Norway 18.3% (BAT 16.3% & STK (62.8%)

Rothmans 2%)

British American Tobacco Plc is set to report higher third quarter 1999 profits, boosted by the first contribution from its acquisition of Rothmans, but the smoke has yet to settle after its share's two-day tumble. The world's second largest cigarette company which markets such brands as Lucky Strike, State Express 555 and now Rothmans, is expected to report nine-month operating profits on October 26 of 1.33-1.40 billion pounds after last year's 1.26 billion. Analysts said on Friday that the underlying trading picture across the world has improved for BAT since the first half of 1999, but trading in the third quarter is still below last year's Q3 after stripping out the Rothmans effect. (CIG Outlet. Net, 2002) However, after an 80 million exceptional charge for acquiring stock following the purchase of its Japanese distributor, high interest charges and restructuring charges in connection with Imasco, pre-tax profits were well down at 220 million, from 308 million for the same period last year. (Citywire Money, 2000) Underlying volumes fell 3% as the recession forced consumers to cut spending, particularly in eastern Europe and Japan. But BAT increased revenue by 17% following acquisitions in Indonesia, Turkey and Scandinavia and by increasing prices. (The Guardian, 2010) BAT's main premium brands Dunhill, Pall Mall and Lucky Strike increased their market share but Kent fell 4% because of weak trading in Russia.

(The Guardian, 2010) The tobacco industry has proved relatively resilient to the recession, with strong pricing power and a wide range of brands that appeal to smokers in developing countries, where western cigarettes are viewed as trophy products. But the global picture is one of overall decline, with volumes falling annually by about 2% as people give up for health reasons or because cigarettes have become too expensive as governments in western countries increase excise duties. BAT did well in the Americas, where profit rose by 134m, mainly due to a strong performance in Brazil, an improved product mix and exchange rate benefits. But volumes were down 6%, illustrating how the company is having to work harder to deliver improved earnings. In 2008, it closed a factory in Denmark in an efficiency drive that is saving 250m a year. (The Guardian, 2010) In 2009, BAT entered Indonesia, the 4th largest cigarette market world wide, which represents a huge opportunity (see table). BAT acquired 85% of Bentoel shares for US$ 494mn. The merger completed in 2010 (6 months ahead of scheduled). A very successful merger reflected in the results (growth in market share to 9.0% (+ 0.9%), volume grew to 23.6 bn, NTO ( 300.6 mn) and profit ( 46.2 mn) exceeding expectation, and total synergy savings of 11.8 m) (Fell, 2010) British American Tobacco, the world's second largest quoted tobacco group has acquired an 85% stake in PT Bentoel Internasional Investama Tbk, for US$494 million (Asia Law, 2009) The reported Group revenue increased by 17 per cent to 14,208 million as a result of the favourable impact of exchange rate movements, continued good pricing momentum, volume from acquisitions made in the middle of 2008 (Skandinavisk Tobakskompagni (ST) and Tekel) and the acquisition of Bentoel Internasional

Investama Tbk in June 2009. Revenue increased by 10 per cent at constant rates of exchange. (BAT News, 2010)

British American Tobacco Plc., Europes largest cigarette maker, has bought a majority stake in PT Bentoel Internasional Investama, the nations fourth-largest cigarette producer, to bolster its stake in the countrys highly lucrative cigarette market. (The Jakarta Post, 2009) BAT bought the stake from various shareholders, including previous majority holder Rajawali Group, a local diversified-business giant, a media statement said Wednesday. Even with the acquisition, however, the company has some way to go to catch up to its bigger rivals. Indonesias cigarette market is dominated by Philip Morris Internationals H.M. Sampoerna (27 percent), Gudang Garam (22 percent) and Djarum (21 percent). BAT previously paid 11.2 times EBITDA for Denmarks ST and 11.4 times for Turkeys Tekel in 2008. Indonesia is an attractive market for any cigarette maker, with Bloomberg reporting that about a third of Indonesias 248 million people smoke, compared to only 21 percent in the United States, according to government figures. (The Jakarta Post, 2009) The price paid for the 85% stake is equivalent to IDR873 per share, a premium of 20% over Bentoel's closing price of IDR730 per share on Monday, BAT said in a statement. despite aggressive moves by the government to raise excise tax revenue from the industry in the past few years. (Dow Jones Deutschland, 2009) Rothmans is a multinational company engaged in the manufacture, distribution and sale of tobacco products, including cigarettes, fine tobacco, pipe tobacco and cigars throughout the world. It is owned by the Compagnie Financire Richemont AG,

incorporated in Switzerland (which owns two third of Rothmans) and Rembrandt Group Limited, incorporated in the Republic of South Africa (which owns one third of Rothmans) (Office for Official Publication, 2009) ANALYSIS AND EVALUATE

CONCLUSION Mergers and acquisitions have proved to be a solution for companies that are trying to improve their competitive position. Still, not all mergers and acquisitions become successful operations. The success of a M&A operation does not obligatory mean that the newly formed entity would generate more wealth for the shareholders. It simply means that the objectives took into account by the managers are fulfilled. These objectives can be translated into bigger incomes, better market shares, improved social visibility or any other improvement persued by the decision maker. (Nachescu, 2011)

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Aicpa MCQ Release Document 2019Document145 pagesAicpa MCQ Release Document 2019anshul goyalNo ratings yet

- Comparing production costs and profitability of NVT and Honda motorcyclesDocument7 pagesComparing production costs and profitability of NVT and Honda motorcyclesrk85mishra100% (1)

- Form 5 Accounting: Transaction Analysis ExerciseDocument33 pagesForm 5 Accounting: Transaction Analysis ExerciseCahyani Prastuti100% (1)

- Financial AnalyticsDocument10 pagesFinancial AnalyticsBiltush Khan100% (2)

- Competitive StrategiesDocument31 pagesCompetitive StrategiesDarshan PatilNo ratings yet

- QnetDocument4 pagesQnetLahiru WijethungaNo ratings yet

- Mission Vision and ObjectivesDocument5 pagesMission Vision and ObjectiveskarunaduNo ratings yet

- OmaDocument57 pagesOmaVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- How To Break Pages & Insert Numbered Headings in WordDocument1 pageHow To Break Pages & Insert Numbered Headings in WordVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14-2. Tobacco CompaniesDocument1 pageChapter 14-2. Tobacco CompaniesVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- The Knowledge Integration Strategy Analysis After Geely Acquisition of VolvoDocument4 pagesThe Knowledge Integration Strategy Analysis After Geely Acquisition of VolvoVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Hipoglikemi Andini Taufiq Vivi LudskiDocument7 pagesHipoglikemi Andini Taufiq Vivi LudskiVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies From A Developed To A Developing Economy: Germany/South African Collaboration in The Automotive IndustryDocument5 pagesCooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies From A Developed To A Developing Economy: Germany/South African Collaboration in The Automotive IndustryVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- DtrycgfhgfhggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggcccccccccccccccccccccccccccccbvnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnntyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyDocument1 pageDtrycgfhgfhggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggcccccccccccccccccccccccccccccbvnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnntyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- P ('t':3) Var B Location Settimeout (Function (If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') (B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Document1 pageP ('t':3) Var B Location Settimeout (Function (If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') (B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Vivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- TauuDocument1 pageTauuVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Data Colected For JournalDocument4 pagesData Colected For JournalVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Sharp Corporation: Company ProfileDocument9 pagesSharp Corporation: Company ProfileVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- 5 Porter Forces AnalysisDocument9 pages5 Porter Forces AnalysisVivi Sabrina Baswedan100% (2)

- 5 Porter Forces AnalysisDocument9 pages5 Porter Forces AnalysisVivi Sabrina Baswedan100% (2)

- MGM-2b Q.2b: Strategies for HRC's expansion to Brazil and ArgentinaDocument2 pagesMGM-2b Q.2b: Strategies for HRC's expansion to Brazil and ArgentinaVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- For MRN 2000 WordsDocument2 pagesFor MRN 2000 WordsVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- AR2010 Markets Vwfsag enDocument16 pagesAR2010 Markets Vwfsag enVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Cbi Group Assignment Answers (Very Rough Draft)Document12 pagesCbi Group Assignment Answers (Very Rough Draft)Vivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Buat Tugas CBIDocument6 pagesBuat Tugas CBIVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Buat Tugas CBIDocument6 pagesBuat Tugas CBIVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- ZukisDocument1 pageZukisVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- JBJXBCJZGJCKGJKV P ('t':3) Var B Location Settimeout (Function (If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') (B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Document1 pageJBJXBCJZGJCKGJKV P ('t':3) Var B Location Settimeout (Function (If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') (B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Vivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Abstract JustinDocument1 pageAbstract JustinVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- HipertensiqsbwiudDocument10 pagesHipertensiqsbwiudVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Bulletpoints For Marketing and StrategyDocument1 pageBulletpoints For Marketing and StrategyVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- DAFTAR PUSTAKA SjfhajhjkhdkjhkjdfkjedgkjfDocument1 pageDAFTAR PUSTAKA SjfhajhjkhdkjhkjdfkjedgkjfVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument1 pageDaftar PustakaVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Abstract JustinDocument1 pageAbstract JustinVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- KDRTDocument1 pageKDRTVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- KDRT Finishhhhhh ViviDocument37 pagesKDRT Finishhhhhh ViviVivi Sabrina BaswedanNo ratings yet

- Jaico Invoice 23Document1 pageJaico Invoice 23bansal book storeNo ratings yet

- Brand ExtensionDocument19 pagesBrand ExtensionSimran NeemaNo ratings yet

- Barco Case AnalysisDocument2 pagesBarco Case Analysiscoolavi0127100% (1)

- Equity Assets - LiabilitiesDocument6 pagesEquity Assets - LiabilitiesAcca IsdcNo ratings yet

- Touchpoints in CRM of LICDocument7 pagesTouchpoints in CRM of LICShahnwaz AlamNo ratings yet

- Mini Project on Supermarkets and Retail BrandsDocument10 pagesMini Project on Supermarkets and Retail BrandsSai PavanNo ratings yet

- Arun Ice CreamDocument3 pagesArun Ice CreamAslam Khan0% (1)

- Atlantic Bundles Software and Hardware for Higher ProfitsDocument15 pagesAtlantic Bundles Software and Hardware for Higher Profitsgaurav vijNo ratings yet

- Role and Functions of AdvertisingDocument10 pagesRole and Functions of Advertisingjsofv5533No ratings yet

- Eticket: Nagercoil Sunday, January 28, 2018Document2 pagesEticket: Nagercoil Sunday, January 28, 2018Abi RaNo ratings yet

- How Much Good SmellDocument1 pageHow Much Good SmellAshutosh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Study Note 2.2 Page (80-113)Document34 pagesStudy Note 2.2 Page (80-113)s4sahithNo ratings yet

- Report On Personal SellingDocument11 pagesReport On Personal SellingGirish Harsha100% (5)

- COPQ KPI How To MeasureDocument2 pagesCOPQ KPI How To MeasureNguyễn Tiến Dũng100% (1)

- Thesis APDocument31 pagesThesis APIvy SorianoNo ratings yet

- Cultivate and Sustain Motivation: Career CatalystDocument6 pagesCultivate and Sustain Motivation: Career CatalystArunkumar100% (2)

- Fenesta CaseDocument14 pagesFenesta CaseAbhay Pratap SinghNo ratings yet

- Travel ConsultantDocument2 pagesTravel Consultantmichiduta_07No ratings yet

- Prospecting, Profiling and Closing the BusinessDocument20 pagesProspecting, Profiling and Closing the BusinessservicerNo ratings yet

- PEV-3C Pressure Equalizing ValveDocument10 pagesPEV-3C Pressure Equalizing ValveSamy CallejasNo ratings yet

- Below Is A Model Answer Based On The Previous CategoriesDocument2 pagesBelow Is A Model Answer Based On The Previous CategoriesBiju PrettyNo ratings yet

- Linear Equations GuideDocument12 pagesLinear Equations GuideTewodrose Teklehawariat BelayhunNo ratings yet

- Ingersoll RandDocument2 pagesIngersoll RandAnkit AvishekNo ratings yet