Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Main Overview of The Quality Problem

Uploaded by

PradeepOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Main Overview of The Quality Problem

Uploaded by

PradeepCopyright:

Available Formats

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

Introduction

This chapter will give an overview of the main quality issues. The chapter is divided into the following sections: 1. Term definition as a basic starting point 2. Why has quality become a modern problem? 3. The phases that have to be distinguished in the entire quality management-, and production- cycle 4. Characteristic phases in dealing with quality problems 5. Developments in the second half of the twentieth century up to the present day

1. Term definition

1.1 Description and properties of the quality concept The dictionary gives four definitions of the term quality; Capacity, specifically of substances and goods with regards its use Property (with regards to the appreciation) of primarily people Condition, worthiness, function; most in the conjunction: in his, in its, etc. (chess game) the value difference between different pieces or combinations thereof The relevant definition is this chapter is clearly: Capacity, status or properties of something in regard to its use Or: The collection of properties of something, that determines whether it fulfils the stated requirements Succinctly stated: fitness for purpose

A-2

Industrial organisation A

The fundamental issue is therefore: the objectives one wishes to achieve with something Three conclusions can be drawn directly from this: 1 Quality is a relative term. When the objective is altered the quality of the relevant properties is also changed. As a consequence these may have to be adjusted. Example: mock ups: cardboard tanks used in the Second World War. 2 Quality is a subjective term. Every subject derives quality from the objective/goal he/she expects or experiences in his/her own personal situation. Depending on the objectives which can change in time one determines ones own, often shifting vision of quality. Example: 20 glasses of beer before, and after drinking them Due to the subjectivity of quality it is often difficult to form an operational basis for the term. At best intersubjective norms are established. Example: the mini: One person will truly find them mini (too small to carry themselves or any noteworthy luggage) while another will find their small size practical or charming, perhaps until he can afford himself a bigger car. 3 It is possible to associate at least one, but more often several, quality aspects to everything we have1. Given the long-term company objective (continuance of the company) the quality of delivered services and products is of prime importance; not just up until the moment of delivery but also thereafter. Not only is a constant and uniform quality of products important one should also consider the reliability of the product during its entire lifetime. See section 1.5.

Example: An idea can be very good (for the return on investment) And it can be useful (for improving the working conditions of certain groups of people) The idea can also be detrimental (for the competitors) and It can be extremely bad from an ecological point of view

The saleability of something is determined by, amongst others, quality, rate of delivery, price and service. Of these four the rate of delivery and the price are uppermost at the moment of purchase. However the quality and service remain daily experiences long after the rate of delivery and price have been forgotten. 1.2 Similarities and Differences with the productivity concept Revisiting the definition of the term quality as a means of fulfilling an objective an analogy can be made with the issues associated with the productivity concept. In module Effectiveness, productivity, en efficiency the term effectiveness was defined as:

1 It seems that there is no exception to this rule

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-3

effectiveness = and : =

Rexpected with a certain means Rintended

= (theoretical effectiveness)

Rreality with a certain means Rnorm (nl. the max. result possible with that means in that situation

(real effectiveness thereof)

This basically amounts to the fitness for purpose as well. Module 432 illustrates how the subconscious use of language fails to clearly differentiate between the terms productivity, effectiveness and efficiency. By applying clearer and better matched term definitions the following could be derived with regards to production: Preality = Pnorm Effectiveness Efficiency Similarly the subconscious use of language relating to the term productivity leads to the muddling up of different aspects: Agreements made versus expectations raised: Rnorm (vs. Rintended) Price versus cost of use (sacrifices): Snorm (in which Sreality can differ from Snorm) Properties of alternative products and services (also with regards to the state of art concerning technology ) versus Results and Sacrifices From the above it may become clear that there is a strong link between the term quality and the term productivity. Not in the sense of the productivity of a production model concerning the production proces of products and services but in the sense of the product or service fulfilling needs, thus is meant the productivity of the produced matter. To be able to apply the term quality operationally it is desirable to restrict it to the extent to which it fulfils the objective; analogous to the term effectiveness. As a result quality practically becomes synonymous for effectiveness; in this case not the effectiveness of a production model for the processing, but of a product or service fulfilling certain needs. 1.3 Quality and value In our perception the terms quality and value lie close together. A high or low quality is quite easily subconsciously translated into a high or low value. In this respect it is also essential to think with clearer definitions and with finer distinction . A high quality in the sense that the objective is fulfilled to a high degree does not necessarily imply a high value. This is indeed only the case when the higher result is useful. Consider the analogy of the choice of production means as deliberated in module 432. A Rpossible with a certain means, larger than Rintended can denote waste. Herewith we return to the subject of value-analysis and through this to the subject of Management of Product Development from a Life Cycle Perspective (chapters 6 and 7

A-4

Industrial organisation A

of Ten Haaf, Bikker & Adriaanse, Fundamentals of Business Engineering and Management). 1.4 Difficulties in the application of the quality concept when multiple functions are to be fulfilled As mentioned earlier, a product or service generally has several quality aspects that can be distinguished. This is directly related to the fact that the product or service can fulfil several functions. Customarily a car can be used to: transport oneself quickly transport oneself safely However a car can also be used for: sleeping in (with e.g. sleeping chairs or in the back of a stationcar) pulling a caravan satisfying needs concerning social status etc. One could express this fact in a formula as follows:

n 1 n 1

[Preal.product ]w.r.t.function i = [Pnorm.product quality* efficiency**]w.r.t function i =

* = measure of function fulfilment ** = Snorm Sreal.

The practical applicability of such a balancing function comes across two kinds of problems: a. the determination per function of firstly Rreality and Rnorm (the question of the determination of intersubjective norms), and subsequently Sreal and Snorm (with the last of these the problems of collective sacrifices for different functions) b. how can the sub-productivities with respect to different functions be lumped together? This may be possible when considering sacrifices (in terms of money) but how to lump differing values such as quick transport and sleeping chairs? For the time being the formula seems to be of significance solely as a conceptual model; not as a quantitative model. 1.5 Difficulties in the application of the quality concept with respect to the time dimension In analogy to the term effectiveness quality is defined as: Rreality with a certain means Rnorm (nl. the maximum result possible with that means in that situation As far as higher quality is accompanied by higher costs, the optimal level of quality, with respect to a function, is reached when the numerator and denominator are equal.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-5

However both can change in the course of time: usually (though not always!) an increased standard of living and technological progress is accompanied with a subconscious increase of Rintended (better education, longer vacations, faster cars, shorter braking distance, etc.)2 in general, as a result of wear and aging, Rreality will decrease3 The conscious or subconscious increase of R intended results in something that was previously considered to be good enough now being regarded as being of lesser quality. Relative decline of the quality does not however necessarily imply that the quality of the product or service has declined in an absolute sense. As far as the absolute quality is concerned terms such as reliability, breakdown degree, and maintainability become relevant. Reliability, considering the practical applicability of the term, is defined as; The probability that a function can, under certain conditions, be performed up to a desired level and for a certain amount of time. For the quantitative determination of the maintainability the following is needed: Definition of the circumstances in which a function has to performed (for a car bad roads or a certain way of driving; for spacecraft extreme environmental conditions; for a fountain pen the pressure differential; the latter is also of importance for flying and thereby also especially the number landings!) The desired level of functioning And considering the fact that probability is a statistical term the determination of the course of the failure percentages uitvalspercentage over time based on large enough numbers. Some products or (sub-) parts are subject to a gradual decline in quality whilst others can have an abrupt decline (i.e. either working or not working); with a light bulb both cases can occur. It makes a difference what kind of use one envisions in time. For example: 1 . Continuous functioning over a longer period of time (dynamos, car and aeroplane engines, light bulbs, waterworks) 2. Functioning for a short period of time, whereby inspection before every period of use is easily possible (sailing of a leisure sailing boat, cutting tools) 3 . One-off use, whereby an inspection of the functioning prior to use is impractical (solid fuel rockets, gun ammunition, matches). While complex systems can begin to show flaws in their functioning in many different ways in time, simple parts usually have the following characteristic tendency:

2 One is, as it were, again unconsciously making a choice of the means, i.e. thinking and feeling in

the strategic level

3 Limits of this statement:

1. 2.

with very simple systems the opposite can be observed for more complex systems: - running in of cars - working in of people

A-6

Industrial organisation A

Figure 1: During a certain start up period the breakdown degree is relatively high; subsequently it levels off and stays constant for a long period of time; at a certain point in time the percentage will start to increase again.

The average chance of survival of a certain product or part can be depicted as follows:

Chance of survival

50 %

50 % Time

Figure 2: The average chance of survival as a function of time used

Under strong development is the so-called reliability engineering.4 Reliability engineering concerns itself with the probability distributions of functioning errors in time. This in contrast to quality control that, amongst others, concerns itself with the probability distribution of errors in a collection of objects at a certain point in time.

4 If desired compare this to chapter 33 of the System engineering handbook of B.E.Machol

(McGraw-Hill Book Company).

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-7

Maintainability is defined, consistent with reliability, as: The probability that once maintenance work has commenced under certain conditions the original level of functioning is restored within a certain amount of time (If desired see chapter 33 for further aspects also in relation to the design that determine the maintainability and reparability). A high reliability or low breakdown degree, as well as a good maintainability, results in lower maintenance costs and costs as a result of lack of use. Subsequently they lead to lower depreciation costs per unit of time and/or a higher residual value. In verbal communication one often associates these aspects with a higher quality. It deserves to be noted that a sharper distinction should be made between: - On the one hand the quality of a function at a certain moment in time - On the other the course of the quality level in time

2. How did quality become a modern problem?

2.1 With seven league boots From Brief specifications for quality maintenance (of which two chapters have been included in supplement I): Even from as far back as ancient Greece and ancient Egypt, descriptions can be found of quality control and written specifications of products. From wall paintings in a grave in Thebe from around 1450 B.C. and illustrations of a textile factory from around 1880 B.C. it is possible to determine that the function of quality controller existed, even back then. In the main economy of the Middle Ages, which was governed by traditional methods and craftsmen, the intervention of traders lead the dissolution of the direct link between producer and consumer. An almost direct consequence was a necessity for a means to record quality requirements between two parties who did not communicate directly. In the line of Basic forms of co-operation (chapter 10 from Ten Haaf/Bikker/Adriaanse Fundamentals of Business Engineering and Management) that is the moment when ground form X steps up: as the first form of indirect cooperation on the basis of specialisation (detachment!) of the operational level. 2.2. Three trends The rapidly increasing importance of the quality problem is closely associated with three trends in modern development. Firstly there is a continuing increased particularisation in the structure of societys production; both in the field of the internal, as well as the external organisation (compare again with chapter 10 from Ten Haaf/Bikker/Adriaanse Fundamentals of Business Engineering and Management). While in the pre-industrial age a direct form of contact existed between the producer and the consumer, in modern times this

A-8

Industrial organisation A

only remains the case in the tertiary sector (the services sector). In the primary and secondary production sectors markedly long and complex production- and marketing structures have developed. The direct feedback of user-experience to the producer has been replaced by a much more complicated system of market- and price-mechanisms. Indeed, as a result of this, the personal contact between the producer and consumer has been lost completely. For the individual worker, who contributes only a small fraction to the realization of a product, it cannot be determined whether his work is in fact acceptable. As a direct result this situation fails to motivate a worker to deliver the required quality. Secondly the anonymous customer can, when relating to scarce products, barely be selective with respect to quality. As long as products are scarce the focal point remains the production of more. Only in a later stage in part due to the pressure of competitors does improvement become important. The significant change over from a producer market to a consumer market in the Western world occurred for the most part as result of the shortages incurred during World War II being replenished in a relatively short and unexpected period time. Of course a different situation existed during the war itself when the government could demand certain quality levels. We quote again from the book Kwaliteitszorg in kort bestek (Brief specifications of Quality maintenance): The Second World War demanded a vast production of military goods in the United States. From a strategic point of view it was necessary to deliver both in accordance with specifications agreed upon as well as to deliver on time. Not only were demands made of products they were also made of industrial organisations. The complete set of rules was written down in the so-called AQAPs (Allied Quality Assurance Publications), which is, in a somewhat newer version, still used today for deliveries to the ministry of Defence. A dominant post-war impulse in the Western world to rapidly give more attention to quality came as a result of Japanese successes in this area: Japan was compelled to rebuild her industry from the bottom up after the Second World War. In the beginning of the fifties made in Japan was synonymous with cheap junk and bad quality. That is the reason why General MacArthur sent for two American quality experts, Juran and Deming, to come to Japan. Thanks to a quick acceptance of their ideas, the Japanese industry now delivers products renowned for their excellent quality. En further on: These developments drew so far ahead of the United States and Europe that the Japanese competitive position would become a threat if decisive action was not taken quickly. The influence of this can be felt up until the present day as many both American and European businesses have discovered to their significant disadvantage. There is a third dominant trend evident from which one can discern that higher demands to the quality of products and service with respect to quality and business certainty have to be made:

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-9

Under influence of technical developments increasingly complex installations and systems are designed and used. Rapidly increasing demands are made to the reliability of such systems. Especially when society is dependent on the reliability of such systems for its immediate functioning: consider water-, food-, electricity-, and traffic systems. But indirectly society is also becoming more vulnerable, for example as a result of the consequences of water- and air-pollution as well as other environmental threats. Attention for quality is rapidly becoming a compelling necessity; for competitive reasons but also for reasons of safety and the environment.

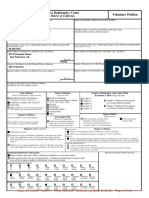

Phases in the total quality- and productionharmonization cycle

As early as the first half of the first lecture of Fundamentals of business engineering and management it has been pointed out that the object of study should stretch out far beyond the more or less technical production processes. This is strongly reiterated in the discussion in chapter 10 Basic forms of co-operation, chapter 4 The main functions in an enterprise and chapter 15 Cost price calculations 1 principles and outlines from Ten Haaf/Bikker/Adriaanse Fundamentals of Business Engineering and Management. In fact what becomes possible during production and later on in use, service and maintenance is determined for the largest part by the design and the care taken in the computation of its construction. (if desired compare this to chapter 6 Management of product development from a life cycle perspective 1 from Ten Haaf, Bikker & Adriaanse, Fundamentals of Business Engineering and Management) as well as the end of An overview of the maintenance problem. A number of essential phases can be distinguished prior to the actual fabrication, just as a number of phases can be distinguished after fabrication, that can be of decisive importance for the final quality result. The Achilles heel of the total process can be clearly illustrated using a different approach already introduced a number of decades ago by Sittig in Meer door kwaliteit (More by quality) (1961, van Sittig and van Ettinger). To that end the following schematic representation of the total process, from market research to the final fulfilment of the needs of the customer: This diagram (Figure 3) shows a clear analogy to the diagram in supplement III of chapter 4 The main functions of an enterprise, as well as chapter 11 Working together in a task group from Ten Haaf/Bikker/Adriaanse Fundamentals of Business Engineering and Management. Reasonably arbitrarily ten phases have been distinguished. In many cases in which the engineer is involved (Technical Marketing) phases 8, 9, and 10 take place at and ought to take place in discussion with the customer (or his or her representative). The principal criterion for the control and realisation of the total process is of course: the optimisation of the cost-benefit balance over the totality of these phases. By considering each transfer factor as an arithmetical factor as well, a quantitative approximation can be made. The total result then presents itself as a continuous product of these factors.

A-10

Industrial organisation A

Q1

market segment

finding of the largest common denominator of necessities of a, supllied by way of a differential model, market segment

Q2

Q10

translation thereof into a, for productand service-packages applicable, list of requirements

service and maintenance

Q3

Q9

design of, with respect to the above, an optimal concept-solution

instruction and training

Q4

Q8

working out, in agreement with all of the requirements, of the construction

transport and installation

Q5

Q7

the actual production

Q6

sale to a suitable customer

Figure 3. Sequence of processes from tracing to providing

Now one may question what values these factors will assume in practice. In order to do so one can interpret each of these factors as the effectiveness of the transfer to the following link: Rreality = Effectivenessreality Rexpected = NORM (maximum result possible in that situation) Considering that doing more for the customer than is absolutely necessary increases the costs without increasing the benefits, one should aim for each of the transformation factors to have a value of 1. With respect to the values that that this factor can have in practice the following three possibilities can be distinguished: there is a loss of quality alignment effect.w<1 there is a gain of quality alignment effect.w>1 there neither a loss nor a gain in quality alignment effect.w=1

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-11

Furthermore considering that interpretation mistakes made when the baton is passed on at least when no serious effort has been made to build in a verification and feedback process! can continue on through the whole series the final result in practice can easily fall well below the desired value of 1.

Example: as early as phase 1 (determination of the average needs situation) it becomes evident that it is almost always impossible to incorporate the total need in the aim or objective. Furthermore certain developments in the relevant market segment will not be completely predictable. In this case one can speak of a tracing quality (K1): the extent to which the largest common denominator has been adjusted to the needs situation of the market segment.

Similar is the extent to which it was possible to derive the requirements made to the product from certain needs (K2 ) the quality of the derivation. Herewith the previously named Achilles heel of the process comes to light. To approximate this quantitatively the erosion of the resulting effectiveness is calculated and presented in the table below for different values of what we can now call erosion-factors; consistently small [but constant] deviations of this factor, relative to itself and per link, from the theoretical value of 1.

Effectiveness per step 1,00 0,98 0,96 etc. etc. 0,90 Loss per step in % 0 2 4 etc. etc. 10 Resulting quality 100 82 66 etc. etc. 35 Loss of quality 0 18 34 etc. etc. 65

Herein one can find exactly the reason why Philips was forced, in the second half of the eighties, to replace the baton model by a much more integrated approach; forced because of the Japanese successes achieved with this approach both in terms of higher effectiveness as well as shorter throughput times. The question as to how a more integrated approach can be influenced in a positive sense receives an answer from the film 4708 Integrated Quality Care. The film begins with a telephone conversation in which a large contractor announces to a director that he is going to stop with reception checks (checks of incoming goods). To justify this seemingly paradoxical measure the condition is stated that from now on all of the delivered goods have to be 100% in order. Moreover the buyer demands a constant quality. In talks with the section heads one wonders whether 5% errors might be acceptable5, or whether the competitor might have more controllers resulting in the competitor being more expensive.

Who would accept an error margin of 5% in his own personal life or in, for example, traffic?

A-12

Industrial organisation A

Thanks to his neighbour the director comes into contact with wholly different type of industry: one that fabricates shirts. In this industry quality is stated as giving the customer what he wants for a reasonable price. In order to do so it is necessary to: to record technological quality requirements to their fullest extent in handbooks. properly educate employees for their function . In doing so the overall-costs are lowered instead of raised. It is apparently essential to subdivide costs of quality into: preventive costs: instructors, training, research etc. valuation costs: measurement equipment, controllers, etc. costs of breakdown (rejection) It has to be known how much controlling costs a company. To incorporate these costs into overhead, thereby making these costs invisible is incorrect. Starting point for the improvement of the quality level has to be: Make things right the first time. To achieve this one will have to accept temporary loss. Quality should be everybodys problem The first step taken in our (film)company is the observation that certain parts are made too exquisitely. In addition the constant character of the quality is investigated. The complete control-system is examined. Every controller appears to have his own standards. Moreover the film shows that these standards are very dubious because controllers unknowingly re-inspect rejected parts (scrap) and subsequently approve or reject a large number of these parts. Next one looks for the machine that causes the mistake. After adjustments have been made one has to keep controlling. Machinecards have to be made and employees have to be kept informed of the results found. The controllers present are given newer and more extensive training. They have to develop from reviewers into quality experts. The turners and millers control themselves and fill out the spot check cards themselves. From error analyses it becomes apparent that 50% of the rejections can be prevented. Not only the employees of the production department, but all the employees of the company (design, accounting, maintenance etc.) are involved in this quality action. After a year has passed the result is that the quality has reached the desired level whereby the total costs have indeed been reduced by 5% in comparison to the preceding situation. As a final idea to further reduce the costs someone suggests to put an end to the reception controls of incoming goods and to demand 100% in order; in fact the same situation comes to pass as when they themselves were put on the spot a year ago. They believe they are entitled to do so and the film ends with the recording of a message to that effect for all of the suppliers.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-13

The same cycle now starts in these companies. The oil spill type effect moves down the value adding chain which is characteristic for these types of processes. The moral of the story Quality is no longer the sole responsibility of the control department. Every employee is responsible for quality because you cannot inspect quality into a product; you have to build it in. For this very reason: Self-control is the best control. The whole workforce should receive: - a good introduction to quality policy - the right training and instruction for the work that has to be done - the right tools and machines - a lasting interest in quality In short, not the control department, but the entire management is responsible for the right quality. One can only truly guarantee responsible, correct and constant quality once all employees in all departments feel a shared responsibility for the quality. (That is why it has sometimes been said that the existence of an independent control-department can pose a threat to the quality.) What then is the function of the control-department in this interpretation? It will start to act as the conscience of designers, constructors, prep-workers, and works foremen. Externally the control acts as a spokesperson to the customer on the topic of quality. The aim is to prevent mistakes and rejections rather than to detect mistakes afterwards. Quality is therefor the result of the effort of all of the employees in the company. Quality can thus be seen as an integrated task for all of the phases from market study, research, design, and production up to and including delivery and service. In short in accordance with that what was shown in figure 2.

4. Characteristic Phases in Dealing with the Quality Problem

In supplement II a complete copy can be found of the relevant article. Thus we can limit ourselves to the two main points of the article. 4.1 The first main point When competitors start to materialise and complaints of customers can therefor no longer be ignored, the first worry of the management is, as a rule: repair or if it is unavoidable replace; and subsequently considering the possible threat of a bad reputation making sure that no further defective products are delivered to the customer [this so called after-sales service costs a lot of money!] In order to do so a final-control is implemented. The next logical step is then:

A-14

Industrial organisation A

How is it possible that we allow so many [or in any case more that necessary] bad products to be created? It is at this point that statistical quality monitoring can prove to be very useful. By registering all of the unacceptable deviations the following question is automatically raised: how controllable are the applied production processes really; and can they be handled in a better way? It is especially at this point that the approaches of two internationally renowned quality gurus Juran and Deming have proven their greatest worth: for the western world both sad and foolish: in the first place for the Japanese competitive position! But what are the reasons why the production processes are sometimes so difficult to control? Or that a properly produced and delivered product turns out to function improperly in practice in spite of this? It is these types of questions that refer back to earlier phases in the value adding chain: to the design-, or even earlier the market- and requirements research phases. Once these phases are controlled both in a quality sense and motivationally can the term Integral Quality Care (IQC) then finally be used? Answer: no! It turns out that even then issues exist for which the quality for the total functioning of the enterprise (i.e. company, establishment, or organisations in general) can be and in time have to be better controlled: the quality of the work on all levels; in conjunction with the quality of the organisation in general, (for these aspects refer to the last part of the article in supplement II points 3, 4 and 5) the quality of the relations: - with buyers - with suppliers - with the authorities on the various levels - with the community in general (especially the neighbouring community) Insofar the first main point. Most companies and establishments have, regarding this point, plenty of work ahead of them. 4.2 The second main point The second main point is of a clearly different nature. This has to do with an everpresent schism in our society. Namely the one between the, what one can term, the b and the a - spheres. Or in other words: with the distinction between on the one hand nature and the strongly dependent technological sciences and on the other the behavioural sciences. In fact in practically all problems of leadership and organisations these two poles can be distinguished. In still other words all activities centre on: how should certain issues be handled or dealt with in order to reach the intended result: the technological or b -pole and for whom and with whom that can best be done; hereby introducing the human aspects as the a -pole.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-15

Similarly for the practical management of the quality problem on all levels, with regards to the previously named aspects: therein it is possible to distinguish both a processing and a statistical-mathematical side as well as a motivational, mentality- and therefor strong cultural component. In the article in supplement II this is addressed: in point 1. under the title bridge functions between scientific management and contributions from the behavioural sciences and in point 5. under the title instrumentations for the bridge function? In terms of the title of this chapter Characteristic phases it can be said that all too often the management sticks to in part due to one-sided advice a too one-sided btechnological approach of the quality problem. This whilst more behavioural scientific advisors often do not have a proper grasp of- or are not competent enough in the application of essential contributions of the a -side. Hence the plea for a systematic development of the bridge functions between these necessary poles of a more synthetic approach. Insofar the second main point.

Developments in the second half of the twentieth century up to the present day

5.1 The application of Quality Circles in Japan and elsewhere Quite soon after the end of the Second World War Japan surprised the rest of the socalled Western World with successive market penetrations which were initially completely unexpected for that corner of the world. Japan was able to do so both on the basis of very competitive prices as well as on the basis of products that possessed an unusually high level of quality and a high reliability. The so-called Western industry repeatedly organised study trips to the land of the rising sun in an attempt to gain insight into the secrets behind this unexpected and unequalled success. One of the participants was ir. F.A. Mulder, at the time scientific fellow of the Technical College Eindhoven, now professor in business administration at the same university who presently gives intercompany training in the business community with great success. Published in Functional Company management from July 1971, he wrote an article with the title Quality care in Japan about the experiences he gained from such a study trip. Amongst other things, the application of so-called Quality Circles was addressed. It may be obvious to allow him his own say in the following quote: The third phase (1961 present) is signified by the involvement of large groups of implementation personnel in research and the improvement of quality, efficiency and productivity. Improvement hereof usually entails the solving of a large number of detail-problems. It is only possible to do so in a short period of time if a large number of people think together and work together.

A-16

Industrial organisation A

The implementation personnel as was the Japanese idea were the first to qualify for this purpose. The group is numerous and knows the problems from up close. The management was able to actually obtain co-operation by placing more emphasis on the recording and analysis of production data on the lowest hierarchic level and by stimulating quality activities of which the Quality Circles (more on this later) are the most prevailing. And indeed later on under the title: Quality Circles The most impressive aspect of the Japanese handling of quality is the extent to which they have been able to make use of implementation personnel to analyse and solve problems regarding the efficiency and the production quality in their direct working surroundings. For the most part this takes place in the form of quality circles: a group of approximately 5 to 15 employees lead by one boss. Around 1962 the first circles developed, now the number of circles is estimated at more than 100,000 (Prof. Ishiwaka, Tokyo University). This entails that more than approx. a million Japanese bosses and workers are learning or have learned to critically analyse their work using straightforward methods (Pareto-analysis, cause-effect diagrams, control cards, histograms, and many others). Still less fathomable for us is that it is done with such enthusiasm and inventiveness. Attempts have been made to randomly calculate the achieved results, however they have not yet been successful. It is known however that the average saving due to the activities reported as part of the Q.C. circle conventions can be approx. Hfl. 200.000,-. In a company with 3000 employees, where 200 quality circles have been formed, four problems per circle were solved a year. The quality circles meet weekly- or once every two weeks for a short period of time (for 1 to 1 and a half-hour) both during and after work. In the latter case the extra hours made are usually paid as overtime. In our visits we have seen the work of quality circles in various companies.

Motivation What motivates the Japanese worker to take part in these activities so energetically and enthusiastically? It is our impression that there are forces at work that centre around certain values that have become imbedded in Japanese culture: national pride, company pride and a strong recognition in the company, the prevalence of group interest above self-interest and loyalty to the group. This is further strengthened by the virtues instilled as a result of education and upbringing; diligence, eagerness to learn, caring for detail and striving for perfection. These forces are activated by the large amount of attention given to education and training and to the making available of simple tools for problem analysis and process control. Extra, materialistic, rewards seem hardly to be of importance: they are completely absent or are of merely symbolic value.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-17

The recognition of a group achievement does on the other hand play a significant role. End of the quote and the article. Many Dutch companies have subsequently attempted to implement these Quality Circles; (or perhaps more appropriately: to imitate?) bravely aided by a new (fashionable?) generation of organisation consultants. Though with very varying and usually unimpressive success. The roots of such an institute reach down much further than the western manager is prepared to accept and is able to handle. In spite of this, or perhaps because of this, an important lesson can be learned from this. Indeed essential is: a style of leadership, whereby the hierarchical boss leaves no question as to WHAT should be done; but at the same time does leave plenty of room as to HOW it should be done a substantially different role for the so-called staff members . They should sooner serve implementation workers than that they should be giving them orders. that the workers are instructed in- and entrusted with- the required (and simple!) methods and techniques. For the more difficult and sophisticated methods and techniques one can indeed make an appeal to staff members who are more specialised in dealing with that specific situation. 5.2 Quality guarantee and certification Origin of the need As the distance either geographically or in time between producer and consumer, i.e. user of (also industrial) items, increases: It becomes more difficult for the buyer to form an opinion beforehand on the quality of that which he or she is considering to purchase. (Quality obviously in terms of: befitting the considered user- and therefor requirements pattern.) As such it becomes understandable why increasing scale and a reduction in trade barriers (for ex. GATT or Euromarket) is accompanied by a growing need to secure this quality as much as possible through different means than by means of direct contact and judgement. Notice in this the cause for the creation of the institutes quality guarantee and certification. For those interested in gaining more in-depth knowledge reading the special issue Certification: not for the rules of the game, but for playing the game is useful. Amongst other it touches on the following subjects: - The strategy for the ISO 9000-series in the nineties. - The myth of certification. - AQAP versus ISO. It is important of course to possess a certain idea of what these norms entail. In supplement IV an overview of these norms is given.

A-18

Industrial organisation A

Risks Experience has taught by now that an unchecked endeavour for a certificate is not free of risk. This may be evident from a summing up of the titles of the previously named special issue: Quality improvement is in essence the steady increase of the problem solving ability in- and of an organisation. This ability is the engine for a harmonious integration of technological and social systems. Certification can be the crank of this engine. If you are not as yet certified, and you do want to be, realise that for companies who did not comply beforehand with norms comparable to ISOnorms (AQAP-NEN) the changes in the company and required effort was much greater. Costs and the required time are clearly higher, while for many of the researched companies the necessity for the change was much higher.

Also in the implementation of the quality system the costs precede the benefits: Costs: Hfl. 100.000,- to Hfl. 300.000,-; average: Hfl. 175.000,-. Personnel: 2 to 3,2 man-years; average 2,5 man-years. Time: 3-5 years.

And further on in this introduction: Conti (one of the authors) signifies the role of the ISO 9000-norms as the bridging of two periods. From a formal point of view they form the last step in the development of quality as a static normalised concept instead of a dynamic process that is based on continuous improvement. The last section of this chapter, What in essence it is about, will go into more depth on the previous topic. Before doing so a statement about the crucial importance of: 5.3 Quality in development and design In the bibliography one can find the book Quality with development and design which we highly recommend for those that wish to expand their knowledge of the material. It gives an excellent overview of the various aspects associated with this. At this point we wish to limit ourselves to the subject that should also be regarded as being of great importance for the engineer. And that concerns, from part 3 Instruments and techniques Chapter 20, the Taguchi method. We quote: Taguchi6 highlights two focal point of the design processes that have been neglected in many industries: a. Realisation of a robust design The sensitivity of the product or process to external (uncontrollable) disruptions is minimised, through systematic research, by means of statistical experiments concerning the relations between product characteristics and disruption causes. b. The costs for lack of quality Too large a spread in the product- or process characteristics is visualised by means of the loss function. Reduction of the spread is achieved by investigating the relations between the product characteristics and the causes

6

Dr. Genichi Taguchi held many positions in the Japanese industry and had the honour of receiving a personal Deming-prize. In the fifties he wrote the book The Design of Experiments.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-19

for the spread. In the past this approach was neglected becaus e the required statistical data and experience in the des ign department was missing. Taguchi teaches us, via simple menu-like methods, to circumvent these knowledgethresholds. (etc. etc.) The Special issue about Statistics from SIGMA 1992 number 6 includes amongst others an article with the title Statistical experimental setup classic, Taguchi or Shainin7 written by dr. Wilhelm G. Kleppman (professor at the college in Aken, section Production technology.) In this article the aim for once is not to emphasise the contradictions between different authors. To the contrary, consciously is shown how sometimes seemingly contradictory approaches can be applied complementary to one another. This is then particularly expressed in the following schematic overview regarding the most important areas of application and the associated aspects:

Method Main area of application Recommended test set-up Taguchi Development Resolution III Classic Shainin

Development and Production Production Diverse collection for Complete factory tests every goal Not uniform Mathematically reliable method Detect important disturbance factors and remove them Simple application

Insensitive for Goals for the handling changes of disturbance of disturbance factors factors, robust processes Other aspects Quality philosophy

Table: Comparison of methods of test set-ups (in complementary perspective)

5.4 What in essence it is about SIGMA number 4 from 1992 presents itself as special issue about the following subject: Quality and the Future: Thinking ahead within the quality care sector The latter is immediately also the title of the first article included. In the article it is established that for the Netherlands there is still a long way to go. In the year 1992: merely two to three percent of the Dutch business community actually applies integral quality care. The rest talks about it at best. Subsequently the manner in which the Netherlands could best deal with the Continuous Quality improvement towards the future is addressed. A report drawn up by Ernst & Young in co-operation with the American Quality Foundation describes the results of a study conducted among 500 companies spread out over three continents. From the study it would appear that a large consensus exists regarding the best approach for the near future. The five key associated concepts are:

7

Dorian Shainin published in 1988 an article in Quality and Reliability Engineering International nr. 4 under the title: Better than Taguchi orthogonal tables.

A-20

Industrial organisation A

the company result or organisational result is no longer just expressed in a single dimension such as return on investment, turnover, or profit margin; but in three dimensions Qualities, Quantities and Costs. focus on the customer needs to be explicitly addressed focus on the competitor needs to be addressed as well process improvement or simplification forms the fourth central point of attention as well as the aspect of employee participation Next to the international quality norm systems such as the ISO 9000 series, it appears that the application of the so-called quality prices is an important instrument for stimulating the efforts of companies in the area of quality. In the past few years the American Baldridge Award and the European Quality Award have acquired a large reputation. A systematic comparison between the three along the lines of the, previously presented, five dimensions is summarised in the following table:

Table: Three assessment systems regarding their future significance Award from the European Foundation for Quality Management Also non-financial measures (cost of non-quality, cycle time etc.) are taken into account Attention is paid to the relevance of the results for each group that has an interest in the organisation. This includes the customers. Key phrase: Customer satisfaction Attention is paid to etc. as above: Including competitors. Emphasis is laid on the identification, evaluation and improvement of the core processes. People satisfaction is important: How do people feel about their own organisation.

Baldrige Award

NEN-ISO 9001

No result assessment; no role for quality in strategy. Only an Quality aspects in product and obligation for quality service are highly valued registration and possession of a quality policy Included in the strategy is the reduction of complaints, exactly fulfilling the specifications of the customer. Key phrase: Customer Driven Quality The quality level is compared to that of competitors and market leaders (via benchmarking). Emphasis on continuous improvement of the processes. Human Resource Utilisation: emphasis on motivation, suggestion-teams, but also Empowerment8 (!)

The customer does not enter the picture.

No mention is made of the competitors

The only emphasis is on the process control.

Outside the scope.

After a closer analysis the article concludes with the following: General final conclusion: The key concepts for the future are clearly:

8

Empowerment means literally: authorise, enable someone to. It basically means delegating more power to act than usual.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-21

Quality also as a result Focus on the customer as well as the competitor Process improvement/simplification and Employee-participation

Concepts that are by themselves decades old, but whose consistent applications are still ahead of us. Proper support from professional literature when attempting to fill in the details is not available (as of yet). To much emphasis is placed on certification and the NEN_ISO. This is all the more troublesome in light of the conservative base of the NEN_ISO 9001, whereby controlling instead of improvement is more important. New light is shed by the Awards: For a good guide towards the future they are presently the most suitable. Thus, in this regard, it is of importance to take deeper note of the structure that form the basis of these awards. We limit ourselves to the European version. The European Quality Award The relevant text is presented here: The technique of Quality Self-appraisal is very useful for any company wishing to develop and monitor its Quality culture. This kind of systematic review and measurement is one of the most important management activities of any Total Quality Management System. Self-appraisal allows you to clearly discern your strengths and areas for improvement, by focusing on the relationship between your People, processes and results. Within a Quality-conscious organisation, self-appraisal should ideally be a regular activity. Application for the Award requires the self-appraisal in the first instance, so it should not be difficult to use your own findings to fit the model in which the Award assessment is based. The Award Assessment Model People, Processes and Results Processes are the means by which the Company harnesses and releases the talents of its People to produce Results. In other words, the People are the Enablers which provide the Results. Displayed graphically, the principle looks like this:

A-22

Industrial organisation A

THE ASSESSMENT MODEL (in terms of) :

PEOPLE - PROCESSES - RESULTS

PEOPLE MANAGEMENT

PEOPLE SATISFACTION

LEADERSHIP

POLICY & STRATEGY

PROCESSES

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

BUSINESS RESULTS

RESOURCES

IMPACT ON SOCIETY

IMPACT ON SOCIETY

ENABLERS

RESULTS

Figure X

Essentially this tells us that: Customer satisfaction, people (employee) satisfaction and impact on society are achieved thr ough leadership driving policy and strategy, people management, resources and processes, leading ultimately to excellence in Business Results. So far the quote from the prospectus for the European Quality Award 1992. One should be totally aware of how fundamental the principle of self-examination is in the approach. It seems the only way to ensure that the highest management makes this issue its own. Al too often this issue is left to the lower echelons. It thus becomes, for an organisation as a whole, evident that the highest management tolerates quality actions but does not regard them as being everybodys highest priority; from high to low. The previous draws a patently clear picture of what it (with the integral approach of this, for the successful survival of companies and organisations, so important question) comes down to. Interesting in this regard is also the chart, borrowed from an old publication of Sittig and Ettinger; the latter being at the time the director of the Building Centre in Rotterdam. It has been included in supplement V. In this way it may become clear that we cannot and therefore should not de facto be satisfied with anything less. This should therefore also have consequences for the education. With prof. ir. N. van Omme appointed professor of quality management at the Groningse University in 1992 we wholeheartedly agree with stating the twofold necessity: that the education in and working on quality care should constitute a permanent part of the functioning of anyone in whichever organisation,

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-23

as well as that it should be a compulsory part of the masters phase of every faculty We will notice

Supplements

I Two chapters from Quality Care in brief - Developments during the ages - Quality policy (as being of overriding importance for every organisation) Publication of the NEHEM s-Hertogenbosch; Author: Chr. J. M. van Grinsven. II Characteristic developments: phases in the management of quality Prof. ir. P. Ch-A. Malotaux; Business Administration, volume 57, 1985/3 special issue Quality and Organisation Contents: 0. Introduction 1. Attention for the quality of products and the production method - Management of the quality problem in scientific management - Implication and effects - Contributions from the behavioural sciences - Bridge-functions between scientific management and the behavioural sciences - The Zero-defects approach - The work structuring approach 2. Attention for the quality of product development. - Fitness for purpose - But at the same time a new problem presents itself (!) 3. Attention for the quality of the work and of the organisation. - more integrated approach possible? 4. Reformulation of the problem quality of work - it concerns the adjustment of the quality: between what the work demands and what the employee wants and is able to do. - introduction of the term grow front 5. Instrumentation of the bridge-function? III IV V Three American quality gurus: differences and similarities in their respective approaches. Overview of quality norms (also for certification) Schematic overview of The increasing scope of integral quality care.

A-24

Industrial organisation A

Chapters 2 & 3 from: Quality Care in brief

(Edition from: NEHEM, postbus 90.105, 5200 MA s-Hertogenbosch, 1986)

Developments during the ages

Even from as far back as ancient Greece and ancient Egypt, descriptions can be found of quality control and written specifications of products. From wall paintings in a grave in Thebe from around 1450 B.C. and illustrations of a textile factory from around 1880 B.C. it is possible to determine that even back then the function of quality controller existed. In the main economy of the Middle Ages, which was governed by traditional methods and craftsmen, the intervention of traders lead the dissolution of the direct link between producer and consumer. An almost direct consequence was a necessity for a means to record quality requirements between two parties who did not communicate directly. The customer was reassured by means of guild hallmarks. During the industrial revolution solving quality problems was mainly seen as a technological problem, which could be solved by making use of machines. Slowly people started to realise that this was a slightly one-sided approach, which resulted in the appearance of more and more control- and sorting departments in companies after the 1920s. Two causes can be identified that helped to further develop quality care. The Second World War demanded a vast production of military goods in the United States. From a strategic point of view it was necessary to deliver both in accordance with specifications agreed upon as well as to deliver on time. Not only were demands made of products they were also made of industrial organisations. The complete set of rules was written down in the so-called AQAPs (Allied Quality Assurance Publications), which, in somewhat newer versions, are still used today for deliveries to the ministry of Defence Japan was compelled to rebuild her industry from the bottom up after the Second World War. In the beginning of the fifties made in Japan was synonymous with cheap junk and bad quality. That is the reason why General MacArthur sent for two American quality experts, Juran and Deming, to come to Japan. Thanks to a quick acceptance of their ideas, the Japanese industry now delivers products renowned for their excellent quality. At first we are now discussing the beginning of the fifties only the final control was introduced, which still contained the risk of missing products of bad quality. Next the controls were placed earlier on in the different production phases, which decreased the number of rejections but also required a large number of controllers. The final step meant the dissolution of the separation between production and control. Everybody in the company was responsible for the quality of their own contribution to the production. The increased involvement of the employees resulted in a better identifying with the company and led to, on the one hand a decrease in the

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-25

number of errors and on the other a significance saving on the control-costs. These developments drew so far ahead of the United States and Europe that the Japanese competitive position would become a threat if decisive action were not taken quickly. In the Netherlands the Department of Trade and Industry made a start a number of years ago. From 1978 to 1980, in the form of an experiment, the so-called Qualityplan was formulated, which was implemented in five branches of industry. The five branches were the graphics, the mechanical parts, the furniture, the shoe and the packing industry. Aside from these branch-experiments, the Dutch Normalisation Institute (NNI) formulated norms for quality systems. Furthermore a beginning was made with preparations for the establishment the Council for Certification, which had become operational in 1983. This central institute defines criteria with which certified establishments, which have been set up in different branches, have to comply. These certificates, granted by these branch-establishments, strengthen customer relations, are positive for the acquisition and thus serve as an ideal basis for promotional activities. Certification can be seen as the end result of the implementation of quality care but it is not necessarily the goal. In different branches we can observe different situations: The graphics industry has had a mature certification system at its disposal for quite some time The quality project in the mechanical parts industry sparked the foundation in 1982 of the Certification Institute for the Mechanical and Electromechanical Industry (CIMEI). The furniture industry issued a label, Furniture from the Netherlands, that is meant to mature into a quality label. In 1982 the quality label was introduced for shoes. The carrying of such a label was linked to an evaluation of the quality system of the company, which guarantees that the information given on the shoe label is correct. In the packing-industry a certificate was not believed to be necessary yet. For the certification of consumer goods a trend can be identified in the direction of a linking of the certificate to a form of guarantee that benefits the customer should the product not comply with the raised expectations. Possibly this linked guaranteed quality will influence the public and thereby quicken the acceptance of these hallmarks.

3. Quality policy

The commission Wagner is of the opinion that with regards to the relations between international competitors and the changing market situation modernising the management of quality care is absolutely essential. The government policy should be attuned to this. Furthermore it is of importance that the government, within the framework of the acquisition- and inspection policy, should take advantage of the increasing quality control in the business environment.

A-26

Industrial organisation A

This is emphasised by the conclusions of the subsequent notices. Export policy from December 1983 in which, as a requirement for a stronger competitive position, the improvement of quality and productivity is named. To prevent confusion in the application of quality terms we state below the definition of product quality as it is used in the NPR 2650 (The Dutch guideline for the implementation of a quality system in an organisation): The extent to which the complete set of properties of a product, a process or a service fulfils the stated requirements, which are a result of the intended use. The Americans state this succinctly as fitness for use. Quality care, as described in the introduction, has to do with functioning of a company. Control of the production process gives the assurance that the products will keep on fulfilling the wishes of the customers. The policy of the company with regards to quality requires an integral approach, in which a number of goals in the areas of product quality, quality control and quality care all in relation to the company results, have to be reached for. All levels within the company will have to be involved in the quality policy and will have to support this policy. A heavy burden will have to be placed on the coordinating, administrating and controlling tasks of the management. When formulating the quality policy for the company use can be made, in accordance with the specific problems of the company, of a number of different methods: NEN-norm 2646 Optimisation of the quality costs Statistical quality control In practice it has hard to tell the difference because it often occurs that elements of these three methods are applied simultaneously. The method according to the NEN-norm focuses primarily on the organisation of the company. Through control, registration and feedback it should be possible to assure that the produced goods and services fulfil the stated quality requirements. This method is mainly applicable to the implementation of procedures. De second method concerns itself with the optimisation of the quality costs. Quality costs are all the costs that can in any way be linked to the quality control within the company. Due, in part, to the often-concealed nature of the costs, they are usually heavily underestimated. In practice it appears that an approach focused more on prevention can reduce other costs, such as evaluation, rejection and the sending back, too such a point that a positive balance results. From the perspective of quality cost analysis the functioning of the quality system can constantly be quantitatively monitored and judged. If, next to the costs, the surplus value as a result of the marketing effect and/or the increase in production is taken into account, then the actual optimal situation lies ahead of the point of the total quality costs.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-27

A third method to optimise the quality of the production process involves a total statistical quality control. This method is based on the philosophy, developed as early as the thirties by Dr. W. Edwards, an improved co-operation between the management and the employees can eliminate mistakes in the system thereby preventing production faults. As a foundation for the discussion between the management and the implementers use is made of a number of statistical techniques, of which the easiest is also understandable for the lesser-educated employee. As such the policy of the management can be determined based on actual and demonstrable facts and not on pretty or disguising words. This philosophy is the most important starting point for the foundation MANS (Management and Labour New Style) that was established at the end of 1983. In a company in which a functioning quality system is already present, one could consider the implementation of so-called Quality Circles. These are groups of three to ten people, from different departments, who attempt to find solutions for quality problems that they are confronted with on the shop floor. It is not merely about the quality of the service and the products but also about the quality of the way in which the person functions within the company. Of course a company can proceed with the individual implementation of quality care if no quality project exists within its branch of industry. The advising and stimulating role, played by the project leader in the branch-project, shall, in the case of the individual implementation and only if required, be fulfilled by an official of the Rijks Nijverheidsdienst (State commerce department). The effectiveness of such an individual approach will rely in part on the scope and the degree of the organisation of the company in question. In summary it can be said that the implementation of a quality policy within a company will have to be undertaken at all levels, from the C.E.O. to the janitor. Everyone is of importance at his own position. It will also have to take place at all stages of the process, productive both directly and indirectly, from an initial tentative market study, the subsequent stages of production until final delivery, in which is included service and after care. The costs of repair and control that have been made up to this point will have to be overcome as much as possible by a system that is focused more on prevention. Everyone in the organisation will have to become aware of his own responsibility and from this starting point become better motivated. In turn, this will lead to a larger degree of satisfaction with the working surroundings. The eventual effects of such a quality care process can be summarised as follows: higher production yield better control of delivery times improvement of ones image less complaints stronger competitive position.

A-28

Industrial organisation A

Characteristic phases in the Management of Quality

It is not always necessary to start all the way back with Adam and Eve; however in the case in question it could turn out to be quite useful and instructive. Let us begin with the basics of the so-called scientific management . These are more than just of large influence on us today: if applied sensibly they can still be very effective. This does not occur however in a single, separate phase, but in perspective of the main division specifically chosen for this article: 1. Attention for the quality of products and the production method 2. Attention for the quality of product development and of the production layout and operation 3. Attention for the quality of the work and the organisation 4. Reformulation of the problem quality of work. 1. Attention for the quality of products and the production method First a characterisation is given of the approach of the so-called scientific management. Subsequently a number of approaches from the social sciences are sketched out. Management of the quality problem in scientific management Contemplation of the quality problem seems to have started during and to a greater extent after the Second World War. Up to the Second World War a standpoint was taken with regards to quality which in essence came down to: Information comes from, or via, the design department regarding the measurements, tolerances or examples of the production such as samples etc. these function as quality norms. The production departments have to meet these requirements After the production the articles are checked: there are good products, there is waste, and there are products that have to be sent back to be reworked. Preferably the controllers do not work directly for the production chefs. The wage of a worker depends in part on the quality that is delivered by him; with piecework or tariff systems this is usually only works to his disadvantage: not good: redo in ones own time or subtract it from production. It is interesting to consider what a well-known organisation expert from those times D.S. Kimball stated in this regard. From his Principles of Industrial Organisation (11th edition, 1939) we quote: It has been shown that the following important principles underlie the economic production of manufactured goods: 1. Division of labour, including separation of mental and manual labour. 2. Transfer of skill.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-29

3. Transfer of thought. Above all things, the inspection system should be a bulwark against the lowering of quality in order to obtain quantity. (pg. 297). Inspection is a judicial function. (pg. 298). The foreman has neither time, nor in general, the information necessary to inspect the product properly. (pg. 300) One of the key points of scientific management is that the most important improvements of the productivity consist of eliminating wastage. This is only possible when wastage is not allowed to form, or in other words when it is prevented. It is therefore peculiar that during this period quality control usually meant: inspection and testing afterwards. The quality norms were established upfront without involving the workers and were checked on their realisation again without involving the workers afterwards. Implications and effects The workers on the operational level were, as a result of this interpretation and application of the scientific method, restricted they could however learn from this to develop themselves in their functioning in three ways: in a vertical sense they lost, because of the strict separation between thinking and doing, contact with the product- and the production-development process; thereby also losing contact with the purpose-giving aspects thereof (estrangement from the development); in horizontal sense, as they were forced to limit themselves to a single or just a few activities, they lost contact with the tangible creation of the products that they perforce contributed to, all in perspective of his adjustment to the eventual use of the product by the customer (estrangement from the production). with regards to the quality controls performed by others they missed both the contact with the purpose of- and the creation of the quality norms as well as the direct feedback of the positive or negative result as determined relative to these norms (estrangement from the quality of the development and the production). Presently it has become especially from the behavioural sciences side (too?) common to look down on that stupid, inhumane, so-called scientific management. However, does one not forget (too?) easily the enormous increase in productivity that have been realised on the basis of her principles? And this in a time when there were hardly any schooled and properly educated workers available? Thanks to the increase in productivity it was possible no mandatory that at a certain point the work times were shortened, and that the time that became available could be used for schooling, education, the formation of up till then unprecedented broad layers of society and free time. These are aspect not only of prosperity but also of well-being.

A-30

Industrial organisation A

After and in the extent to which this was realised the negative effects of the three estrangement categories became current. Delayed by the Second World War the effects surfaced massively during the sixties. In retrospect it is easily stated, that as an error of reasoning in scientific management can be seen: that while it is particularly useful even essential to analyse the work once it has been split up into its determining parts; it does not imply that one has to implement the work in its various parts (only synthesis on the organisational level instead of bringing it down to the organisational level). One could also summarise this history as follows: in the initial situation this solution was adequate; as a consequence of its success new forms of synthesis have become necessary (the old forms are no longer adequate). Contributions from the behavioural sciences? Historically, company psychology and sociology came about as a result of the socalled Hawthorne-studies performed by General Motors in the late nineteen-twenties and beginning of the thirties. Primarily set up because of a need of the management to further increase productivity by optimising the physical working surroundings these studies became the reason for the conception of the so-called human relations approach. In hindsight it can be said that, in their first decade, neither company psychology or sociology nor the human relation movement developed a direct relation with the quality problem of products and production. One could say that the primary focus was on the problems of the social estrangement of the employees in companies and organisations; those that were more explicitly or implicitly organised according to the efficiency principles of scientific management. In short it can be said, that engineers and economists focus themselves solely on their work; that the behavioural scientists focus solely on the person and his social relations; and that neither group focus on the relation between the person and his work. Bridge-functions between scientific management and contributions from the behavioural sciences? After the Second World War the development from producer- to consumer-markets accelerated. Together with the increased rate of development of technology and science, the increasing complexity of products and services and the methods of their production, the requirements made of quality were sharpened; both for the products to be produced as well as those to be bought, as well as their production methods. As a result the necessity grew for increased attention from the higher levels in the hierarchy for the quality issue; also in a more integral sense.

Main Overview of the Quality Problem

A-31

One of the consequences because of this was that it also became necessary on the operational level to be quicker and more effective in the feedback of the production quality. A logical next step was to put the worker in charge of the testing of his own work. Modern measurement techniques and the application of statistical fundamentals enhanced this possibility. In this framework fits the dissertation of Th. L. Stok, the Labourer and the visualisation of the quality (1959). Psychologist himself, he based his study on, amongst other things, the publications of the sociologist L. Festinger, who argued that every human being has the need to be able to perform determinations of self-worth. By applying to this the term, originally from cybernetics, feedback he was able to conclude that two influence stem from this visualisation: one on the work of the labourer, i.e. on the quality of the delivered production one on the labourer himself; on the attitude with which he performs his work. The work of Stok can thus be seen as contributing to the building of a bridge between on the hand scientific management and the human relations approach on the other. In this context two methods of approach can be placed that were initiated in the industrial world in the sixties: on the one hand the so-called Zero-defect programme on the other the so-called work structuring approach The Zero-defects approach This approach came about more or less because of a coincidence in the American rocket- and spacecraft industry. Early on in 1962 at the height of the Cuban missile crisis the American Department of Defence requested of the Martin firm from Orlando (Florida) that they deliver an order of a battery of fourteen rockets fourteen days earlier than was initially agreed upon. Nevertheless the agreed price and a flawless functioning of the delivered battery had to be guaranteed. The Martin firm promised a number of things and took two measures. The first was a twofold intensification of the quality control in the production departments. Then they informed the personnel of the seriousness of the national situation. They appealed to the personnel that they work faster but that they did not make more mistakes than usual. The result was so surprisingly favourable that one had to ask oneself what was really the cause: the more intensive control or the appeal for co-operation of the personnel involved. One repeated the test now without the intensified control and again the result was above the expectations. The findings in themselves were not astounding. One had addressed the individual person, one had informed him and appealed to his personal sense of pride about his craftsmanship and to his self-interest.

A-32

Industrial organisation A