Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nccah Fs Childwelservcda 2en

Uploaded by

georgesways247Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nccah Fs Childwelservcda 2en

Uploaded by

georgesways247Copyright:

Available Formats

child & YoUth health

CHILD WELFARE SERVICES IN CANADA: ABORIGINAL & MAINSTREAM

The addition of a new section (s.88) to the Indian Act in 1951 cleared the way for provincial laws to apply to First Nations people living on reserve. Following this change, provincial child welfare authorities apprehended large numbers of Aboriginal children in the 1960s and 1970s, now known as the 60s scoop (Bennett et al., 2005). Social workers placed some of these children in residential schools, while many others were adopted into non-Aboriginal homes. Due to federal/provincial funding disputes, apprehensions were usually the only child welfare service provided to Aboriginal communities (Ibid.). Aboriginal peoples began forming their own child welfare agencies in the 1970s, and the movement towards self-government continues. However numerous challenges remain. Most disturbing is evidence that another scoop of Aboriginal children appears to be underway, driven by systemic disadvantages in Aboriginal communities coupled with the drastic under-funding of First Nations child welfare agencies by the federal government (Blackstock et al, 2005).

Historical context

First Nations, Inuit and Mtis peoples in Canada have traditional systems of culture, law and knowledge that have provided effective protection of their children for thousands of years. Despite their diversity, Aboriginal1 peoples continue to share a high value for children and an emphasis on the caring and teaching responsibilities of extended family and community (Gough et al., 2005). European colonization of North America imposed foreign, and often harmful, policies on Aboriginal families (Blackstock, Trocm & Bennett, 2004). The federal residential schools policy removed tens of thousands of Aboriginal children from their homes over several generations, aiming for assimilation. Many of these schools were rife with child abuse and neglect (Bennett et al., 2005).

1 Aboriginal in this fact sheet refers to First Nations, Mtis and Inuit peoples. First Nations will sometimes be subdivided by Indian Act status (status/nonstatus) or by residence on/off reserve. Comparisons in this information sheet are usually between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, but some are between First Nations and non-Aboriginals or among Aboriginal groups

sharing knowledge making a difference partager les connaissances faire une difference

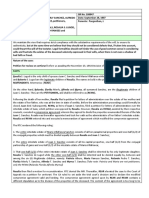

Role of Aboriginal Communities in Child Welfare in Canada, 2007

Developed by the author with reference to: Bennett, 2004; Bala et al., 2004; Mandell et al., 2005; Gough et al., 2005 A = Aboriginal peoples Prov. = Provincial government Fed. = Federal government FN = First Nations

Governmental Authority A Fed. Prov. Prov. Prov. Prov.

Lawmaker A A (Fed. approval) A (Fed/Prov approval) Prov. Prov. Prov.

Services A A A A A (partial) Prov.

Funding Control A Fed. Fed. On reserve: Fed. Off reserve: Prov. Varies Prov.

Potential Application All FN on reserve Most likely FN Usually FN All All

Self-Government Band by-law (*one instance) Tripartite Agreement (*one instance) Delegated Delivery Support Services (Partially delegated service delivery) Mainstream Services

Todays Patchwork Framework

powers for a specified purpose, retaining overall authority. A growing number of Aboriginal child and family service Piecemeal progress towards selfagencies now provide delegated child determination for Aboriginal peoples welfare service delivery, either with full or in Canada has produced a patchwork of partial mandates. Under the full delegation child welfare models serving Aboriginal model, the province delegates the full children. These models can be compared range of child welfare services to the by asking: Who is the government authority, makes laws, delivers services, and Aboriginal agency or community (on or off reserve), including prevention, family controls funding? support, protection, and guardianship. Partially delegated agencies (support The most common models serving services) provide only a limited range Aboriginal children at this time are of services, most often prevention and mainstream services and one of two guardianship. Generally the province Aboriginal-run models: 1) partially delegates authority to an Aboriginal delegated service delivery, which community to provide certain child typically provides support services and welfare services pursuant to provincial guardianship; and 2) fully delegated child welfare law. In two unique cases (see service delivery, which provides support and child protection services.

Mainstream Services

above table), Aboriginal nations have a form of delegated authority over child welfare law and policy in addition to delegated service delivery. Most Aboriginal people see delegated models as a transition to self-government (Bala et al., 2004).

Self-Government Models

Self-government is the framework under which most Aboriginal peoples wish to support their children (Mandell et al., 2005). It includes not only Aboriginal service delivery but also Aboriginal self-governing authority over policy and funding. This basic typology masks significant variation in region, cultural context, urban/rural context, provincial policy, and formal structure. A few of these variations will be briefly highlighted:

First Nations

Many Aboriginal children are still served by mainstream provincial child welfare services in which provinces make the legislation, mandate and regulate service delivery agencies, control funding, and act as the overall governmental authority.

Delegated Models

Delegation is when provincial and/ or federal governments grant specific

Piecemeal progress towards self-determination for Aboriginal peoples in Canada has produced a patchwork of child welfare models serving Aboriginal children

Because Indians are a federal responsibility under Canadas constitution, the federal government plays a more prominent role in First Nations child welfare, particularly in funding. In 1991 the federal government established a program known as Directive 201 to fund First Nations child and family service agencies on reserve.

This applies everywhere except Ontario, where agencies on reserve are funded by the province, which is then reimbursed by the federal government pursuant to an earlier agreement. There are now about 125 First Nations child welfare agencies in Canada, including both fully mandated agencies and agencies that provide partial support services (Bennett, 2004). Delegated agencies under the Directive 201 program are struggling with massive underfunding, receiving 22% less than mainstream agencies despite greater community needs (McDonald & Ladd, 2000). Outside cities, First Nations families off reserve are likely to end up in mainstream services. Some First Nations child and family service agencies are expanding their service delivery to include members off reserve. However, this involves negotiating a second funding agreement with the province as the federal government will not fund services off reserve (Mandell et al., 2005).

In addition to the question of service delivery, there are two ways First Nations have been able to gain some control over child welfare law and policy short of selfgovernment (Bala et al., 2004; Mandell et al., 2005). The Spallumcheen First Nation in B.C. established a child welfare band bylaw in the early 1980s. The power to enact a band by-law is delegated by the federal government to the band under the Indian Act, and each by-law requires the approval of the federal Minister of Indian Affairs. No other child welfare band-by laws have gained ministerial approval. Alternatively, the power to enact child welfare laws was delegated to the Sechelt First Nation in 2003 through a tripartite agreement with the provincial and federal governments. Some First Nations, such as the Nisgaa, now have self-government agreements that include authority over child welfare, and are working to establish policies and services under this framework (Bennett et al., 2004).

Inuit

Child welfare services in Nunavut are part of the territorial government, a unique example of self-government. However, there are no Inuit delegated agencies in other areas (Bala et al., 2004).

Mtis

There are several Mtis child welfare agencies operating at various levels of delegation, providing fully mandated services or partial support services (Bala et al., 2004).

Urban Aboriginal Child and Family Services

Several cities in Canada have Aboriginal child and family service agencies that serve members of all Aboriginal nations. These are usually funded and delegated by the province (Mandell et al, 2005). Manitobas Aboriginal Justice Inquiry Child Welfare Initiative recently established a system of First Nation, Mtis and non-Aboriginal

child welfare authorities that assist clients throughout the province determine the most appropriate agency to provide services (Ibid.). The reconciliation movement in child welfare is bringing Aboriginal peoples and the mainstream social work profession together to acknowledge the uncomfortable truths in child welfares past and present, and to build a new relationship based on self-determination.

This movement goes hand in hand with the broader movement towards self-government, especially because the issues driving family difficulties in Aboriginal communities are systemic. They require a multi-dimensional community-based response, extending beyond individual child welfare agencies, to address economic development and holistic inter-generational healing (Blackstock et al., 2005).

References

Bala, N., Zapf, M.K., Williams, R.J., Vogl, R. and Hornick, J.P. (2004) Canadian Child Welfare Law: Children, Families and the State. Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing. Bennett, M. (2004) First Nations Fact Sheet: A general profile on First Nations child welfare in Canada. www.fncfcs.com/docs/FirstNationsFS1.pdf Bennett, M., Blackstock, C., De La Ronde, R. (2005) A literature review and annotated bibliography on aspects of Aboriginal child welfare in Canada. 2nd Ed. Ottawa: First Nations Child and Family Caring Society. www.fncfcs.com/docs/ AboriginalCWLitReview_2ndEd.pdf Blackstock,C., Loxlely, J., Prakash, T. and Wien, F. (2005) Wen:de: we are coming to the light of day. Ottawa: First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. www.fncfcs.com/docs/WendeReport.pdf Blackstock, C., Trocm, N., & Bennett, M. (2004) Child maltreatment investigations among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal families in Canada, Violence Against Women, 10(8), 901916. Gough, P., Bala, N., & Blackstock, C. (2005) Jurisdiction and funding models for Aboriginal child and family service agencies. CECW Information Sheet #30E. Toronto: University of Toronto. www.cecwcepb.ca/DocsEng/JurisdictionandFunding30E.pdf Mandell, D., Blackstock, C., Clouston Carlson, J., Fine, M. (2005) From child welfare to child, family, and community welfare: The agenda of Canadas Aboriginal peoples. In N. Freymond, & G. Cameron (Eds.), Towards positive systems of child and family welfare: International comparisons of child protection, family service, and community care models. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. McDonald, R.J. and Ladd, P. (2000) First Nations Child and Family Services Joint National Policy Review: Final Report. Ottawa: Prepared for the Assembly of First Nations, First Nations Child and Family Service Agency Representatives, and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development

foR moRe infoRmation: UniVeRsitY of NoRtheRn BRitish Columbia 3333 UniVeRsitY WaY, PRince GeoRge, BC V2N 4Z9

1 250 960 5250 nccah@unbc.ca www.nccah.ca

20092010 National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Production of this document has been made possible through a financial contribution from the Public Health Agency of Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Farming Project SummaryDocument16 pagesFarming Project Summarygeorgesways247No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Incotex 133Document1 pageIncotex 133georgesways24740% (10)

- Chapter X (Secs. 182 To 238) of The Indian Contract Act, 1872Document25 pagesChapter X (Secs. 182 To 238) of The Indian Contract Act, 1872Asmi SNo ratings yet

- Canon System SoftwareDocument5 pagesCanon System Softwaregeorgesways247100% (2)

- Personally Identifiable Information (PII) - The 21st Century ThreatDocument12 pagesPersonally Identifiable Information (PII) - The 21st Century Threatpp3naloziNo ratings yet

- Scope of Works-TSF Ore Rehandling To ROM PadDocument6 pagesScope of Works-TSF Ore Rehandling To ROM Padgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- Syllabus Bookkeeping-Career Diploma: Program Code: BK PrerequisitesDocument5 pagesSyllabus Bookkeeping-Career Diploma: Program Code: BK Prerequisitesgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- SPA TO PROCESS (Loss OR CR)Document1 pageSPA TO PROCESS (Loss OR CR)majoy75% (4)

- Motion For ReinvestigationDocument5 pagesMotion For ReinvestigationGigiRuizTicarNo ratings yet

- Offer LetterDocument2 pagesOffer LetterIpe ClosaNo ratings yet

- War On DrugsDocument7 pagesWar On DrugsLj Brazas SortigosaNo ratings yet

- Revised Code of ConductDocument58 pagesRevised Code of ConductMar DevelosNo ratings yet

- CA Affirms RTC Ruling on Implied Admission Due to Failure to Respond to Request for AdmissionDocument8 pagesCA Affirms RTC Ruling on Implied Admission Due to Failure to Respond to Request for AdmissionIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- Doh Vs CamposanoDocument2 pagesDoh Vs CamposanoMary Grace Sevilla100% (1)

- (Project Title) : The Common Fund For Commodities 12 Open Call For ProposalsDocument12 pages(Project Title) : The Common Fund For Commodities 12 Open Call For Proposalsgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- Kiddie Ride - Normal ModelDocument13 pagesKiddie Ride - Normal Modelgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- CYL Answers LG3Document8 pagesCYL Answers LG3georgesways247No ratings yet

- 5G Network Architecture - 5G Protocol StackDocument9 pages5G Network Architecture - 5G Protocol Stackgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- Bookkeeping Practice Set 3 Solutions Parts 1-5Document3 pagesBookkeeping Practice Set 3 Solutions Parts 1-5georgesways247No ratings yet

- Configuration Guide For BIG-IP Access Policy ManagerDocument542 pagesConfiguration Guide For BIG-IP Access Policy Managergeorgesways247No ratings yet

- IIFTESTDocument30 pagesIIFTESTgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- Hiren Boot CDDocument20 pagesHiren Boot CDGabriel Illanes BurgoaNo ratings yet

- Backup Codes 786Document1 pageBackup Codes 786Richa Sen100% (1)

- ChangeshjhjkhjkDocument5 pagesChangeshjhjkhjkChilmy FarouqNo ratings yet

- 2014 Stock CertificateDocument1 page2014 Stock Certificategeorgesways247No ratings yet

- 2014-2015 Tanzania Tax GuideDocument16 pages2014-2015 Tanzania Tax GuideVenkatesh GorurNo ratings yet

- Reporting GuidelinesDocument2 pagesReporting Guidelinesgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- MashimbaDocument1 pageMashimbageorgesways247No ratings yet

- Jay Akshar Pati PurushottamDocument6 pagesJay Akshar Pati Purushottamgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- Shayona Bee Safari 7 Plus 1 19 - 21 Dec 2016Document1 pageShayona Bee Safari 7 Plus 1 19 - 21 Dec 2016georgesways247No ratings yet

- Sched LG UDocument7 pagesSched LG Ugeorgesways247No ratings yet

- Quick Start Guide for SanDisk SecureAccessDocument21 pagesQuick Start Guide for SanDisk SecureAccessbijan034567No ratings yet

- Shah Garment Variation: TOTAL 17,728,000Document1 pageShah Garment Variation: TOTAL 17,728,000georgesways247No ratings yet

- Research Report PosterDocument4 pagesResearch Report Postergeorgesways247No ratings yet

- General Information: Body Dimensions - DI-2Document1 pageGeneral Information: Body Dimensions - DI-2georgesways247No ratings yet

- Sched LG UDocument7 pagesSched LG Ugeorgesways247No ratings yet

- Make Your Own VGA Cord of CAT5 Cable! Soldering Is Fun!2Document4 pagesMake Your Own VGA Cord of CAT5 Cable! Soldering Is Fun!2georgesways247No ratings yet

- Pinnacle Hollywood FX v5.2.48 + 3068 EffectsDocument7 pagesPinnacle Hollywood FX v5.2.48 + 3068 Effectsgeorgesways247No ratings yet

- LIC's Jeevan Anurag PlanDocument10 pagesLIC's Jeevan Anurag PlanMandheer ChitnavisNo ratings yet

- Only The RFAM (Rolando Florida Alfredo Myrna) )Document2 pagesOnly The RFAM (Rolando Florida Alfredo Myrna) )Vernon ArquinesNo ratings yet

- Bid ShoppingDocument9 pagesBid Shoppingabhayavhad51No ratings yet

- Mr. John SmithGIRLS TOUCH RUGBY Alyssa Chan Jenny Cheng Jenny Chung Jenny FungDocument24 pagesMr. John SmithGIRLS TOUCH RUGBY Alyssa Chan Jenny Cheng Jenny Chung Jenny FungTara MorrisonNo ratings yet

- 2020 08 24 Mauritius Final Country ReportDocument373 pages2020 08 24 Mauritius Final Country ReportLiam charlesNo ratings yet

- Lease DeedDocument3 pagesLease DeedKranthikumar SuryadevaraNo ratings yet

- RA-Republic Act No. 10175Document13 pagesRA-Republic Act No. 10175Ailein GraceNo ratings yet

- UBC Vs Agaba KamukamaDocument6 pagesUBC Vs Agaba KamukamaKellyNo ratings yet

- David Terry Kidd, Jr. v. John Doe Edward W. Murray E.C. Morris Benjamin R. Hawkins Larry D. Huffman Mr. Lawsen Ombudsman John B. Taylor Larry W. Jarvis Steve B. Hollar Faye W. McCauley W.E. Jack James R. Thompson Scott Miller R. Humphries, Correctional Officer Diane Cubbage Russ Fitzgerald Gary L. Sanderson Kathy Fries Lynne Graham Cox Cynthia Nuckols Pat Guerney, and Commonwealth of Virginia Virginia Parole Board Department of Corrections Staunton Correctional Center Circuit Court for the City of Waynesboro 25th Judicial District Mary Sue Terry Stephen R. Rosenthal Pamela Anne Sargent Clarence L. Jackson Lewis W. Hurst Gail Y. Browne John A. Brown Jacqueline F. Fraser Doctor Saddoff Doctor Gardellia Doctor Ozinal Rod G. Griffith Mary Ann Whaley Wendy G. Dodge Lisa Wilhelm Dee Dee Hall Michelle Woods Bob Cash Judith Cash Kaye Marshall Diane Motley Thomas E. Roberts, Clerk of Court, City of Staunton Brenda Morris Judith Owens John Robert Lewis, Jr. Michael M. Clatterbuck Phillip ColtranDocument2 pagesDavid Terry Kidd, Jr. v. John Doe Edward W. Murray E.C. Morris Benjamin R. Hawkins Larry D. Huffman Mr. Lawsen Ombudsman John B. Taylor Larry W. Jarvis Steve B. Hollar Faye W. McCauley W.E. Jack James R. Thompson Scott Miller R. Humphries, Correctional Officer Diane Cubbage Russ Fitzgerald Gary L. Sanderson Kathy Fries Lynne Graham Cox Cynthia Nuckols Pat Guerney, and Commonwealth of Virginia Virginia Parole Board Department of Corrections Staunton Correctional Center Circuit Court for the City of Waynesboro 25th Judicial District Mary Sue Terry Stephen R. Rosenthal Pamela Anne Sargent Clarence L. Jackson Lewis W. Hurst Gail Y. Browne John A. Brown Jacqueline F. Fraser Doctor Saddoff Doctor Gardellia Doctor Ozinal Rod G. Griffith Mary Ann Whaley Wendy G. Dodge Lisa Wilhelm Dee Dee Hall Michelle Woods Bob Cash Judith Cash Kaye Marshall Diane Motley Thomas E. Roberts, Clerk of Court, City of Staunton Brenda Morris Judith Owens John Robert Lewis, Jr. Michael M. Clatterbuck Phillip ColtranScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- LOGIC PROPOSITIONSDocument6 pagesLOGIC PROPOSITIONSSam BundalianNo ratings yet

- Yojana January 2024Document64 pagesYojana January 2024ashish agrahariNo ratings yet

- Market Power and Externalities: Understanding Monopolies, Monopsonies, and Market FailuresDocument19 pagesMarket Power and Externalities: Understanding Monopolies, Monopsonies, and Market FailuresLove Rabbyt100% (1)

- CVNG 1012 Unit 1 Introduction To LawDocument4 pagesCVNG 1012 Unit 1 Introduction To LawMarly MarlNo ratings yet

- Contributor Agreement Form - AMPSDocument10 pagesContributor Agreement Form - AMPSEntorque RegNo ratings yet

- Ong Yiu v. CA DigestDocument1 pageOng Yiu v. CA DigestOne TwoNo ratings yet

- 1.sarmiento Vs ComelecDocument3 pages1.sarmiento Vs ComelecRhoddickMagrataNo ratings yet

- LTD Module 4Document30 pagesLTD Module 4ChaNo ratings yet

- CRPC ProjectDocument23 pagesCRPC Projectbhargavi mishraNo ratings yet

- Spring Air ModelDocument22 pagesSpring Air Modelwa190100% (1)

- People V Largo, GR No. L-4913Document4 pagesPeople V Largo, GR No. L-4913Jae MontoyaNo ratings yet